Growing up in the last Century: WASHINGTON IN THE 1970s; FIRST TASTE OF CAPITOL HILL

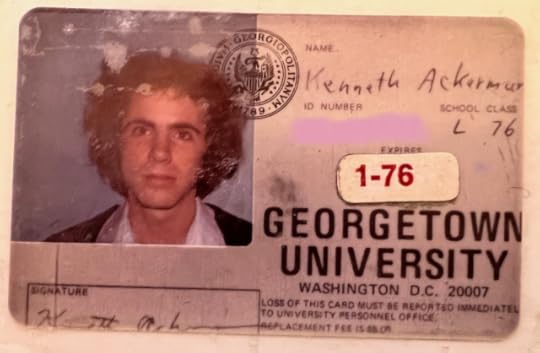

What I looked like on first arriving in Washington D.C. in August 1973, fifty years ago, to start law school.

What I looked like on first arriving in Washington D.C. in August 1973, fifty years ago, to start law school. 1973 had been a big, messy, turbulent year in my life. That January, I’d gone to Rome, Italy, for a study abroad semester, then promptly dropped out of school. I spent the next six months floundering. I landed first in Israel where I lived mostlyon a beach in Eilat with hippies and other dropouts, doing day labor, puttingmy parents through purgatory. Back home,I managed to graduate college (Brown University) without showing up, relying on old Advance Placement credits and snubbing my own graduation ceremony.

I moved in with my parents in upstate Albany,New York, and refused to get a job. I rebelled against anything that came to mind. Tempers flared; thank goodness for my amazinglypatient older sisters and brothers-in-law who ended up acting as reluctantbuffers. I saw a “shrink” for the firsttime (yes, that’s what they called them back then) who accomplished nothing.

Then, after allthe ups and downs, the turmoil and consternation, I landed finally in a weirdlylogical place, at the Georgetown University Law Center in Washington, D.C.

How did thathappen? It’s been fifty years now, halfa century, since I first came to settle here in the DC area. Here I would put down roots, meet my wifeKaren of 38 years, have multiple careers, buy cars and houses, grow older. But back then in 1973, who knew what mightlast, if anything? We were all still shockinglyyoung, me, my friends. The city was oldbut changing. Hardly recognizable fromtoday, we and it both.

From Hippie to Law School

I had never actuallywanted law school. My Dad was a lawyer,and he never seemed to like it much. ButWashington itself was another matter, especially during that unique period ofthe 1970s.

Before 1973 I hadbeen to Washington only twice in my life. And, nojoke, both times I’d had tear gas thrown at me by the National Guard. I had been a student protester against the VietnamWar, first in November 1969, then May 1970 after the Cambodian invasion and theshootings at Kent State University. (Seeearlier blog: Growing Up in the Last Century: Tear-Gassedin Washington DC, May 1970.) These marcheswere fabulous events, drawing hundredsof thousands, the political Woodstocks of that era. I hardly realized at the time that they were shapingme, planting seeds in my mind.

Then, by summer1973, like millions of others, I became mesmerized by the next new drama fromWashington: Watergate, and especially the day-by-day soap-opera-like hearingsof the Senate Watergate Committee under its chairman Senator Sam Ervin (D-NC). I watched them obsessively sitting at home inAlbany, stewing over what to do with my life, fascinated both by the TVjournalists and by all the Senate staffers sitting just behind the Senators andseeming to pull the wires. Who couldimagine a better job than that, right at the center of the action? I couldn’t help but wonder. How do you become one of them?

Back in college,my parents had pushed me to take the Law Boards and I agreed, mostly just to humor them. I was so dismissive that I didn’t bother to prepare, didn’t study. Still, I scored well enough – perhaps because I felt no real pressure - thatmy parents again pressed me at least to apply, at least as a backup. So, fine, I applied to two law schools, oneon the East Coast, one on the West. Georgetownsaid yes, the other said no. All ofwhich led to my third trip to Washington, D.C., in June 1973, to see this GeorgetownLaw School for myself. I’d never visitedor had an interview at the school while applying, so I made an appointment forone now.

On to Washington

I took the trainfrom New York, traveling by myself since I had alienated most of my family andfriends by then. Reaching DC, I walkedthe few blocks from Union Station. GeorgetownLaw had recently moved into a new building on New Jersey Avenue at the foot ofCapitol Hill. That day happened to bethe day John Dean, President Nixon’s recently fired White House counsel and nowchief accuser, was testifying before the Ervin-led Senate Watergate Committee,just a few blocks away. The law schoolhad me wait in the faculty lounge for my interview, and here I watched a gaggleof professors mingling around a TV watching the hearing, chatting about it. What struck me was this: their banter made clearthat virtually every one of them was connected somehow to the big show. This one was advising the Senate, that one theWhite House. Another was best friendswith a key staffer and repeated some delicious gossip, yet another had a columnin that day’s Washington Post or Star.

Georgetown Law School, as it looked in 1973, about half-a-dozen

Georgetown Law School, as it looked in 1973, about half-a-dozen blocks from the US Senate Office Buildings,

All this, not tomention Sam Dash, yet another Georgetown Law professor and friends with all theothers, his face right there on the TV screen as Senator Ervin’s committeechief counsel. Here they all were atGeorgetown Law School. Before myinterview even started, they’d sold me on the place.

All the angst andfloundering of the prior year, my neurotic 1973, seemed to resolve itself withthis choice. Maybe I had just beenlooking for control over my own life, a chance to call my own shots. My parents seemed relieved, and so didI. They’d foot the tuition bill; Icommitted to stick it out. And so it went.On one level, Washington,D.C. seemed like a scarred city when I moved there in August and found anapartment within bicycling distance of the law school (since I didn’t have acar). The apartment was between 6thand 7th Streets SE on Independence Avenue on Capitol Hill. Justfive years earlier, in 1968, riots following the assassination of Dr. MartinLuther King had come within a few short blocks of this spot. Many parts of the city remained unrepairedfrom the fires and damage. Capitol Hillrowhouses that today sell for multiple millions of dollars sat on the marketuntouchable. The term “gentrification” wasn’tbeing used yet to describe changes in the wind for neighborhoods like CapitolHill; it would take another decade or so for those to take root. But walking the streets or shopping in thelocal stores, tensions were inescapable.

Richard Nixonstill sat in the White House, J. Edgar Hoover had only recently vacated the FBIby dying in office, and memories of recent police confrontations at anti-warprotests and in the riots after the killing of Dr. King remained fresh.

Buta new energy also seemed to permeate the city in 1973. New waves of people had come here during theKennedy and Johnson years, and the Watergate scandal itself brought a certainglamour to Capitol Hill. Scores of youngpeople wanted to work there and in the press. A Washington music scene was bubbling in places like the Cellar Door inGeorgetown, WHFS on the radio, Irish music at the Dubliner, jazz at BluesAlley, bluegrass at the Birchmere in Arlington, dancing at Déjà Vu, folk at theChancery across the street from Georgetown Law, plus all the big rock concertsat RFK stadium, the Warner Theater, and on the Mall.

Finally, Capitol Hill

Ittook until my third year of law school before I finally had the chance to plantmy flag on Capitol Hill itself. I signedup for a “clinical” program on Legislation where I would get course credit forworking as a Senate intern while taking seminars team-taught by a professor,Roy Schotland, and a working Hill staffer, MichaelPertschuk, the future FTC chairman and then-chief counsel to the SenateCommerce Committee. Finding aCongressional internship meant knocking on doors in the Senate office buildings,no appointments, no friends or contacts, just carrying my sparse resume andasking for a chance.

Ittook until my third year of law school before I finally had the chance to plantmy flag on Capitol Hill itself. I signedup for a “clinical” program on Legislation where I would get course credit forworking as a Senate intern while taking seminars team-taught by a professor,Roy Schotland, and a working Hill staffer, MichaelPertschuk, the future FTC chairman and then-chief counsel to the SenateCommerce Committee. Finding aCongressional internship meant knocking on doors in the Senate office buildings,no appointments, no friends or contacts, just carrying my sparse resume andasking for a chance.

After many triesand failures, I finally got lucky and landed a spot in the office of Senator ChuckPercy (R.-Ill.). Percy was then the top Republican on the SenateCommittee on Government Operations, soon to be expanded and renamedGovernmental Affairs, today Homeland Security and Governmental Affairs.

Senator Percy atthe time was a leading national figure, a liberal Republican back when thoseexisted: conservative on finance but anti-war, anti-Watergate, pro-civil rightsand political reform. He looked andspoke like a Senator straight from central casting, handsome, baritone voice,articulate enough to debate William F. Buckley on his Firing Line TVshow one day, then tangle with Nixon’s White House or Chicago’s autocraticMayor Daley Sr. the next. And theGovernmental Affairs Committee itself, under its chairman Senator Abe Ribicoff(D.-Conn), was experiencing something of a renaissance. It hadrecently produced the landmark 1975 Congressional Budget and Impoundment Act,was considering high-profile reforms stemming from the Watergate scandal, and wouldsoon handle key proposals from President Jimmy Carter to create newCabinet-level Departments of Energy and Education. Its Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations,chaired in the 1950s by none less than Joe McCarthy (R.-Wis.), held eye-poppinginvestigations that often grabbed headlines.

The Senate Government Operations Committee, circa 1973, when I first came to D.C. Henry Kissinger is the witness; Senators include (from left) Jacob Javits (R-NY), Bill Roth (R-Del), Chuck Percy (R-Ill), and chairman Abe Ribicoff (D-Conn).

The 1975-76academic year would be brutal for me, working by day on Capitol Hill, nightclasses at Georgetown Law, then followed by an even-more-brutal summer of 1976preparing for the bar exam while taking two more courses needed to finishschool. All this was capped by amid-summer week that included the two-day bar exam, a term paper, plus twofinal exams.

After that last exam, I was spent. All I could manage was to stagger back to mysmall apartment and polish off a bottle of Wild Turkey while staring intospace, no drugs needed. Those were the days. A few days later, I remember joining some friends at the Bicentennial fireworks onthe National Mall amid a crowd estimated at a million people. I still rememberthe brownies we ate and how they made the fireworks extraordinary.

Withlaw school now finished, my Capitol Hill internship soon turned into an actualjob as a young committee staff counsel working for SenatorPercy. There is a popular Washingtonstereotype of all those young Congressional staffers in their twenties pretendingto run the world, thinking they’re smarter than everyone else. That was me in the mid-1970s walking about theUS Senate, arrogant, entitled, mostly scared to death that I was totally out ofmy depth, faking the whole thing.

The La st Great Senate

The Capitol Hillof the 1970s is hardly recognizable compared with the hyper-partisan,dysfunctional Congress of today. Myfriend from those years Ira Shapiro, who was also a staffer on the SenateGovernmental Affairs Committee, captured it in a book he wrote called TheLast Great Senate. It was awonderful place to work, especially as a first job out of school. Like those old Upstairs-

Downstairs TV dramas,the Senators promenaded the national stage while their staffs behind the scenesmingled together in their own world. Partisan divides existed, but we were all friendly back then, Republicansand Democrats. One friend compared it toa college campus, the lawns and buildings and restaurants, the differentcommittee staffs like the different academic departments.

On our Committee, GovernmentalAffairs, the Democratic Chairman Ribicoff and Ranking RepublicanChuck Percy, my boss, saw eye-to-eye on most big things, despite a long list of policy differences. Sen. Percy’sfavorite catch phrase, repeated after any tough meeting, was simply this: “always disagreewithout being disagreeable.” And what akick it was to sit at a table (or rather just behind it) with the likes of Ribicoff,Percy, Jacob Javitz (R.-NY), Charles Mathias (R.-Md.), Lawton Chiles (D.-Fla.),Tom Eagleton (D.-Mo.), Sam Nunn (D.-Ga.), John Glenn (D.-Oh.), so on – all householdnames back then and members of the Governmental Affairs Committee. Seeing them interact, these smart,strong-willed people, each eccentric in his own way, haggling over issues andlegislation like a sophisticated game of three-dimensional poker, countingvotes and hatching schemes, put all those dry theories of legislation in anentirely new human light.

It wasn’t all flowersand roses. Senators had bigpersonalities, with temper tantrums and egos to match. We staffers saw plenty. Some Senators were prima donnas treating theirstaffs like maids and servants. Some showedup drunk at hearings or floor debates (alas, no more with C-Span on thejob). Others failed to do homework,then botched simple questions or speeches or sat clueless in key meetings. Once, while we were having a staff meeting ina committee hearing room, an aging senator walked in and wandered aroundtotally bewildered, unaware of where he was or what he was doing, until SenatorPercy tactfully spoke with him, calmed him, and walked him to his destinationdown the hall.

I was the youngestlawyer on the staff, so I was assigned at first to cover issues involving the PostOffice and Civil Service. For SenatorPercy, the most important of these was to keep an eye on the Federal Hatch Act,which bars partisan politics by career civil servants. Percy came from Chicago, then ruled byold-time Democratic Boss Mayor Richard Daley Sr., and Percy had made fighting politicalcorruption a major theme in his campaigns. My directive on the Hatch Act wasthis: “Don’t let them do to Washington, D.C. what Mayor Daley does to Chicago.” Hands off!!

Oddly, thisassignment would place me in the middle of two major events of the Jimmy CarterAdministration: the Bert Lance hearings and the Civil Service Reform Act of1978.

The Lance Hearings

Things had startedbadly between our committee and President Carter’s White House. In mid-1977, a scandal erupted involving T.Bertram Lance, the Director of the Office of Management and Budget (OMB), a topjob in any administration and overseen by our committee. Lance, before coming to Washington, hadheaded the National Bank of Georgia, and Federal bank regulators identified severalirregularities at Lance’s bank. Thescandal escalated into hearings and accusations. Newspapers assigned teams of investigators todig up dirt. Percy and Ribicoffpresented a united front on the controversy, both demanding that Lance resign.But Lance refused and the issue turned bitterly partisan.

It all culminatedin public hearings that September of 1977, covered gavel-to-gavel on CBS networktelevision, the first such televised hearings since Watergate. For our Governmental Affairs Committee, thismeant all hands on deck. Even as thejunior lawyer on staff, I soon found myself poking my face onto the TV screen,one of those staffers sitting behind the Senators as the hearings unfolded, theones who had impressed me so much during Watergate.

The publicity was glaring;given the enormity of it at the time, it is remarkable how this event is solargely forgotten today. It was fun at first. When I spoke to my parents athome in upstate New York, they reported how their friends had seen me on TVand, of course, had focused on the important points: “Why can’t Kenny get ahaircut?” “His suit looks terrible onTV?”

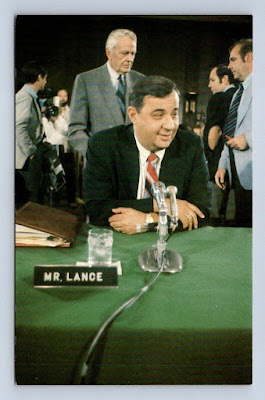

Bert Lance before Governmental

Bert Lance before Governmental Affairs Committee in 1977.

But when Lancehimself finally came to testify, the hearings turned highlyconfrontational. We received deaththreats, directed at Senators and staff alike. At one low point, Carter’s WhiteHouse accused Senator Percy of taking illegal gifts, free airline flights, froma lobbyist. Fortunately, Percy was ableto produce a cancelled check within hours proving he had paid for the flightshimself and the story was fiction, but Carter’s team never retracted norapologized. To poison the well further,several Senators made public accusations against senior committee staff membersbefore it was over.

Within days afterthe hearings, Lance resigned his post at OMB and tempers started to cool. Now I learned another lesson: how politiciansmake peace. After all the bad feelingfrom the Lance hearings, Senators Ribicoff and Percy wanted to heal the wound. Senator Percy was facing re-election in 1978and eager to find a good positive issue to present the voters in Illinois.

Civil Service Reform

The opportunitycame in early 1978 when President Carter announced his landmark proposed CivilService Reform Act of 1978, which he hoped to make a centerpiece in hispost-Watergate commitment to reform government. It would be the first major rewrite of civil service rules since 1883,when Congress passed the original Pendleton Act after the 1881 assassination ofPresident James A. Garfield by a purported disappointed office seeker. (The experience would later lead me to write a book about the Garfield story called DARK HORSE.)

The opportunitycame in early 1978 when President Carter announced his landmark proposed CivilService Reform Act of 1978, which he hoped to make a centerpiece in hispost-Watergate commitment to reform government. It would be the first major rewrite of civil service rules since 1883,when Congress passed the original Pendleton Act after the 1881 assassination ofPresident James A. Garfield by a purported disappointed office seeker. (The experience would later lead me to write a book about the Garfield story called DARK HORSE.)

And as the bottom-of-the-totem-pole lawyerhandling Post Office and Civil Service issues on the Committee, I found theproject landing squarely on my desk.

Congressional staff members can spend decades working in the House orSenate without ever having the chance to handle a major bill from start tofinish, from hearings to markups to floor debate to conference committee, allin a single year. But so it was for me with the Civil Service ReformAct, an amazing learning experience. Therewere many high points. Probably the mostentertaining was the conference with the House, where we squared off againstour counterpart House committee, led by Congressmen Mo Udall (D.-Az.) and EdDerwinski (R.-Ill.), two smart, funny, creative legislators who knew how to cuta deal. Their antics lit up the room.

The most lastingimpression, though, came earlier. At onepoint just before reaching the Senate floor, the bill became stuck as twoSenators, Ted Stevens (R.-Al.) and Charles Mathias (R.-Md.), put “holds” on it,trying to win concessions for their Federal-employee constituents. We staffers negotiated for weeks with noprogress. Then the Senators got involvedpersonally, but again no progress. Finally, President Carter, seeing his high-profile initiative injeopardy, decided to intervene personally and try to break the logjamhimself. Carter invited the four keySenators, Ribicoff, Percy, Mathias, and Stevens, for a face-to-face, privatemeeting at the White House. As the Senatorsand President spoke behind closed doors in the Oval Office, we stafferswere directed to sit and wait in the nearbyCabinet Room - my first time in the West Wing. After the meeting ended, the Senators came out and told us that they’dreached a deal. Then they drove off,leaving us staffers behind to scratch our heads and figure out the details.

The President Steps In

There we sat inthe Cabinet room, joined by some White House staffers. Aftera few minutes, as we were trying to decipher what came next, a door opened atthe far end of the room and in stepped a familiar-looking man in a suit. I was at the far end of the table and it tooka minute to recognize him as President Carter. We were all a bit startled; we weren’t expecting him. He had come by himself, standing alone, nostaff at his side. He seemed shy,introduced himself in a quiet voice, told us he really appreciated our work, then went around the table and shook hands with each of us.

I had never met a President before in a small group setting likethat. Maybe it was the day, but heseemed tired, face drawn, too many meetings, compelled to go through themotions for this one more group. Maybeone of his aides had insisted. Maybe hejust didn’t want to say no. Carterstayed for just a few minutes, then left through the same door where he’dentered, again thanking us. Nobody took snapshots.

It’s alwaysdangerous to read too much into a single brief encounter, but I always took thisday as a cue for why Carter became a one-term President. Perhaps he just didn’t enjoy it enough. (Clickhere, by the way, for my take on the Carter presidency.]

We finished thebill. They held a big signing event forit at the White House for the Senators, Congressmen, and key lobbyists. And yes, Senator Percy would use it in his reelectioncampaign that year – a surprisingly close race, but that’s a story for anotherday.

White House signing ceremony for Civil Service Reform Act of 1978.

White House signing ceremony for Civil Service Reform Act of 1978.End of an Era

For me, the 1970sended abruptly on Election Day 1980. Itwasn’t that Ronald Reagan won the White House. All the pollsters predicted that part. The surprise came later that night when Republicans captured control ofthe Senate, the first Senate party flip in 25 years. I had spent that night watching electionreturns at a house party for staffers from our Governmental Affairs Committee,mostly Democratic. It was a wrenching,emotional affair. As the hours passed,many people in the room saw their jobs disappear, their future plans turned upside down. Our group of friends was being broken up. I would avoid election-watch parties foryears after that.

The next morning,Republican Senators and staffers were elated. There were celebrations among the winners, shell shock for thelosers. In one Democratic office, pinkslips were circulated at the staff Christmas party. Senator Percy, on the winning side, becamehead of the Foreign Relations Committee, a longtime aspiration. In the new regime, I was assigned at first toa new Governmental Affairs subcommittee where Percy become chairman. One of my first assignments was to hand outparking spaces to the staffers, including the now-minority Democrats. My instructions: “Treat them the exact same waythey treated us.” On our subcommittee,there were sixteen parking spaces and the Democrats had previously given the Republicansthree. So, with mathematical precision,I returned the favor - another lesson in partisanship.

Within months, mytime on Capitol Hill came to an end. That June, I joined the Reagan Team, taking a job at a small financial regulatoryagency called the Commodity Futures Trading Commission, but, again, more onthat some other time.

I would return toCapitol Hill many times over the years, including another round as staffcounsel, this time to the Senate Committee on Agriculture working for Democraticchairman Senator Patrick Leahy (D.Vt.). Inthe 1990s when I became an agency administrator (USDA crop insurance chief), I wouldappear regularly, presenting testimony at committee hearings and markups,finally sitting at the adult’s table and participating in my ownvoice, having staff support of my own.

But what adifference those half-a-dozen years made. By 1980, I was still immature, mixed up, wouldn’t meet my wife foranother couple of years, and still had only the vaguest sense ofdirection. But I also knew that I hadsomething important under my belt, a taste for living history, being part of myown era, having an impact. It made mehungry for more. Stay tuned.

newest »

newest »

Cool

Cool