S. Venugopal's Blog

July 11, 2025

Elisabeth the Musical, and the infinite shades and shadows of suicide

Máté Kamarás playing His Majesty Death in Elisabeth (2005) | Black-and-white photo; all rights belong to the original owners

Máté Kamarás playing His Majesty Death in Elisabeth (2005) | Black-and-white photo; all rights belong to the original ownersContent Warning

This piece discusses depression, death, bereavement, grief, sexual assault, and suicide in the context of art, cinema, and social media. Reach out to these helplines for immediate assistance and support if you are in distress, and avoid this article if you are not in a safe position to interact with such content.

Our family’s Amazon Prime membership was swiftly and furiously killed off mere seconds after the first advert interrupted the film that was being screened at the time, and then we all had to find new ways to make our black screens sing for us again.

Full-length Carnatic music concerts, Bollywood vintage hits, and crappy Netflix replacements (always the fifth or ninth thing you wanted to see; never the first or even the second) tried to rescue us. During that desperate time, a dear artist-friend of mine sketched a wonderful illustration of an actor from Elisabeth: the acclaimed 1992 German-language Austrian musical re-imagining the life and murder of Empress Elisabeth of the Habsburg Empire, as narrated by her assassin. Intrigued by such an enthusiastic recommendation, I gave it a watch and will never be the same again.

Part I: Introducing Elisabeth

Empress Elisabeth of Austria in Courtly Gala Dress with Diamond Stars, by Franz Xaver Winterhalter | Wikimedia Commons

Empress Elisabeth of Austria in Courtly Gala Dress with Diamond Stars, by Franz Xaver Winterhalter | Wikimedia CommonsA lonely young girl who stumbles into the heart of an empire, Elisabeth falls in love with His Majesty Death (the personification of her longing to die), and then spends the rest of her life trying to fend off this very handsome reaper who adores her, instead choosing life and the mortal men who only bring her sporadic happiness.

As of my writing this, Elisabeth is likely the most successful German-language musical in existence. Created by Michael Kunze and with music by Sylvester Levay, Elisabeth’s home is gorgeous, decadent Vienna, where it has been performed more than 1,000 times by an ever-evolving cast of actors over the last 33 years. There are also versions of Elisabeth in Hungarian, Korean, Dutch, Russian, and Japanese (performed by both mixed gender and female-only acting troupes), with the musical’s depictions of death and sexual desire varying across cultures and as per regional LGBTQIA+ laws, because Elisabeth’s Death energetically grabs and kisses and fondles and waltzes with suicidal people of all genders.

My friend recommended the 2005 Vienna revival production of Elisabeth because it features the magnificent Hungarian actor-musician Máté Kamarás, who plays a somewhat androgynous embodiment of Death. (Kamarás himself rejects this description, but by Indian standards any clean-shaven man at this point of time is considered an androgynous rarity in our society, so the label fits.)

In Elisabeth, Kamarás’ Death takes the form of a lover who first stalks Empress Elisabeth and then her son Rudolf, wielding his demonic beauty to exploit their suffering mental health and literally seduce them into committing suicide.

Please take two minutes out of your day and find yourself a clip of Kamarás performing Die Schatten werden länger (The Shadows Grow Longer) from Act 1, where Death entices Elisabeth after a devastating loss. In a matter of seconds, you are imprisoned by the haunting sweetness of Kamarás’ voice, the steely perfection of his hunter’s expression, and the crushing effort he hurls into every second of his performance, his forehead turning starry with sweat.

Empress Elisabeth, played with regal determination by the masterful Maya Hakvoort, pushes back using her stubborn beauty and boldness in every song; she sinks the entirety of her faith into her youth, her appeal, her powers of persuasion, and her right to seize contentment in this life—not the next. Death seeks to overpower her during her highest and lowest moments. The Empress dances with him and finds pleasure in his loving attention, but ultimately rejects Death with a vehemence. All of this is narrated by her murderer Luigi Lucheni, played by an electric Serkan Kaya in whose feverish performance of melodic screams you will not find a single missed note.

After I finished watching the musical for the first time, I was so overcome that I had no idea how to really talk to anyone about what Elisabeth did to me.

And so, this piece.

Part II: Infinite Shades and Shadows of Suicide

The following section discusses spoilers and major plot points from the musical Elisabeth, as well as controversial descriptions of depression and suicide. You can skip to the next section if you do not wish to read this.

Elisabeth’s focus is on its titular character and her soul’s triumph over her lifelong urge to die. However, the character arc that crowned the musical for me was the one featuring her son Rudolf’s struggle with depression.

Rudolf’s real life counterpart was a liberal crown prince and womaniser who was traumatised by his father’s conservative court politics and his own unhappy childhood. At the age of 30, he killed a teenaged girl named Mary Vetsera and then himself in the Mayerling Hunting Lodge on January 30, 1889, though accounts vary. The political implications of this act are tremendous, with some history scholars going so far as to speculate that if Rudolf lived to become the emperor, he might have altered the course of World War I and perhaps even challenged the ascent of Nazism with his relatively progressive politics. (Hitler was born just three months after Rudolf’s suicide.)

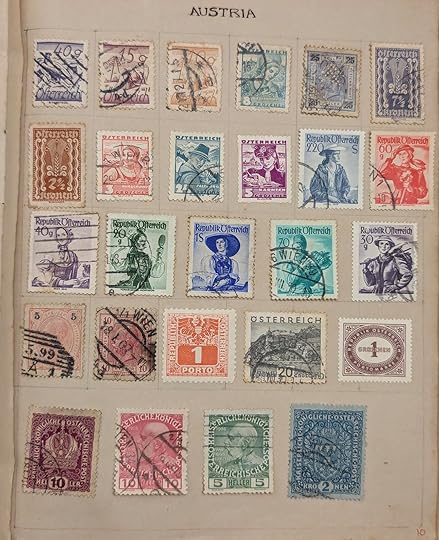

Emperor Franz Joseph I, who died in 1916, outlived his son by more than 25 years and his wife by more than 15 years. Here are some stamps that feature him in his later years, with ‘Österreich’ referring to Austria while ‘Magyar’ refers to Hungary.

Why should you care about his son Rudolf, the suicidal 19th century Austrian crown prince afflicted with a sexually transmitted disease? A book that I read as a companion piece to Elisabeth answers this eloquently:

“And Rudolf, too, became in time a sad but significant precursor. He was the herald of an alienation common to the youth of our day. Over him loomed Franz Joseph, a storybook incarnation of The Establishment. Today The Emperor has been computerized into a system willing to grant its children lordly perquisites and sexual license while remaining resistant to all essential reform […] The shots in the Vienna Woods were fired in 1889. Today and every day hundreds of other unnerved fingers are already crooked into hundreds of other triggers. Each time we hear of another strange young death in a “good” house we hear of another Mayerling.”

Excerpt from Morton, Frederic. A Nervous Splendor: Vienna 1888-1889. Little, Brown, Boston, 1979

The musical’s version of Rudolf is softer, less controversial, and easier to accept as a victim when you do not know his story. His first moment of glory comes in the Act 2 rendition of the song Die Schatten werden länger (The Shadows Grow Longer). In it, the distressed crown prince flings himself into his bed covers for relief, only to realise when the honeyed singing begins that he is sprawled in the lap of Death himself.

The song is everything that could go wrong and yet is a masterpiece that will be explored and dissected for decades. Unlike his mother Elisabeth, Rudolf is unable to resist Death’s alluring caresses and lyrics. He lies close to his killer for one second but veers away from his fatal kiss in the next. So Death quickly changes tactics. Over the course of three minutes, Death systematically breaks Rudolf’s mind and his soul with a duet that tries to convince the young man (or anyone suffering with suicidal thoughts, for that matter) that ending it all is the most rational choice, the most understandable form of self-defence in a world where you can do nothing but witness the ascent of evil and the collapse of order as people around you refuse to see the truth and the shadows lengthen.

Death suddenly throws Rudolf forward and dances brokenly with his weak, unyielding partner like a puppet, marching the helpless crown prince across the stage and controlling his attempts to escape while coaxing him to accept that last kiss. Rudolf barely escapes with his life by ripping himself free, but Death knows they will meet again for that final embrace soon enough.

Most of Death’s actors in Elisabeth opt for a light touch or a moderately aggressive execution of this grotesque yet suggestive dance. They illustrate the metaphor or symbolise the psychological turmoil, but Kamarás takes the abuse to a wholly different plane. He wrings and throws and squeezes and twists and flips and bends back his co-actors as if they are washcloths, all the while shouting in their faces and snarling in their ears even when his pitch takes a beating because of his exertion. The metaphor is no longer a metaphor in his clenched hands; Kamarás throws aside poetry and directly demonstrates how a person’s suicidal urges shake them boneless before dragging them forever into darkness. A prisoner wrenched around the stage before thousands, Rudolf cringes and stares and bows his head and grips Death himself for stability, seeing the truth of the whole terrible world yet not being allowed to see how he could save himself.

It was the most horrific performance I have ever watched, and the most healing. It flipped my stomach inside out and turned me into a useless pile of shocked flesh for over a week after I first saw it, but settled my soul. Why? Because Die Schatten werden länger was a scaffolding upon which thousands of others could throw their pain over Rudolf’s anguish and spread theirs out for careful and dignified study, deciding how to dismantle it entirely or build it into something that sustains life instead. The song will serve this purpose for generations, as it is already doing.

Elisabeth marked the first time I saw an artistic depiction of a person’s struggle with depression that showed the clean, unmistakable separation between an intelligent person and their all-consuming urge to die, instead of welding the two into one ailing mass and diluting both their inner and outer torments. I am not alone in this; numerous YouTube comments under videos of Die Schatten werden länger speak about the catharsis of seeing one’s own shamefully suppressed war against suicide being handled onstage with such artistic courage and audacity, without becoming a preaching cliché. During and after multiple renditions of Die Schatten werden länger, the applause and screaming go on for so long that Death skulks off while poor Rudolf has to wait and look distraught until the chaos fades and the orchestra can safely begin his next scene.

Elisabeth’s songs are a far cry from the clumsy depictions of suicide in Indian mainstream films, where mass deaths of women guarding their imagined purity are celebrated even today and warm the hearts of male religious fundamentalists. Suicide is also commonly employed in Indian cinema to get rid of pesky female characters and propel their inert male lovers into the heroic redemption arc. Rudolf’s suicide, however, comes after a fight with his father and then a separate emotional confrontation with his mother where she refuses to get involved in his affairs (both meanings apply here). It takes as little as that to bring one to their end.

Over the next few days, I spent every minute of my free time running to the strangest corners of the internet to hunt down every version of Die Schatten werden länger that I could find, purely to see how each of Rudolf’s actors brought to life their interpretation of a suicidal man. Andreas Bieber’s Rudolf, for example, staggers in a daze under cold blue lights like a shell-shocked survivor whose legs cannot bear his weight. Lukas Perman’s Rudolf pulls out a voice through his stomach and intestines that is soaked with hurt. Fritz Schmid’s Rudolf is alert but brittle with an aged weariness he has gained too early. Jesper Tydén’s Rudolf is rigid and distracted because his hard, focused gaze is already fixed on the other world. Thomas Harke’s Rudolf bends back into impossible angles to show just how far he is gone. Thomas Hohler’s Rudolf grins with helpless happiness when Death touches him, before snapping his features back into a princely glare. A Dutch Rudolf looks as if he has not slept for weeks and fumbles to button his jacket after Death releases him. Another Dutch Rudolf smiles stiffly to mimic wellness and get back some of his personal space. A Korean Rudolf clutches his heart and frowns up at the sky but later appears close to tears. A Hungarian Rudolf sings like one who is intoxicated and flinches at every sudden movement.

At the end, all I learned was that suicide has infinite shades and shadows, and that no two suicidal people look alike. Wherever I go now, I recognise countless Rudolfs in the faces of those around me, and it is nothing short of cosmic horror.

Yet, it is necessary.

Part III: Conservatism and the decline of art

The original 1992 performance of Elisabeth starring the melodious Pia Douwes in the titular role featured veteran German actor-singer Uwe Kröger as His Majesty Death. Kröger plays a far more non-binary Death with near-angelic detachment and an almost operatic delivery of his lines and lyrics. Even so, when it is time for him to shine in the minute-long Mayerling Waltz sequence, he claims the scene for himself by pulling off a dance move that requires inhuman levels of strength and sensuality, rightfully triggering audience screams and cheers for over 20 years. I cheered as well this year, albeit through a grainy screen and burning with envy as I watched the audience throwing flowers onstage for him after the show, wishing I could do the same. I consoled myself with Instagram hearts and Spotify playlists of his songs.

Both Kröger and Kamarás were under 30 during many of their early Vienna performances for Elisabeth. I point this out because I was splayed out on the floor in shock when I saw these rising actors taking command of such a controversial and taxing role during a time I had always regarded as being fiercely conservative. In particular, Kamarás joyously acted with a senior colleague cast as his love interest, while middle-aged Indian megastars in 2025 call us to the theatres to watch censored cuts of them creeping around actresses young enough to be their children. They have the power to demand better roles but they choose not to.

This is not to say that good art should exclude sexual elements; instead, we need more intelligent portrayals of explicit themes in art to counter the far more common bad faith portrayals. Here, again, Elisabeth excels.

Kamarás’ visibly erotic interpretation of Death is peerless but still divides Elisabeth fans to this day. As for me, I think the existence of his performance is even more necessary and braver today than it was 20 years ago. Watching the 2005 ProShot version of the musical in 2025, I was shocked by how subversive it felt to be experiencing Elisabeth in a world where supposedly liberated Western BookTok influencers now extol the virtues of “clean” books (thereby implying the existence of “dirty” classes of literature) and the Indian film censor board orders even the mildest trace of spice in a film to be turned into sawdust. Conservative Indian rabble-rousers across religions wail about Pride marches and women dancing at bars but fight viciously online for their right to marital rape and honour killings. Bollywood answers their complaints with films that are choked with degrading yet tedious sex scenes (if they make it past the censor board) and wasted violence and CGI explosions and scowling terrorists wearing more eyeliner than I did during my Evanescence years.

On the other side of the world, Kamarás’ performance of Death as he pursues an empress and then a prince is fearlessly passionate, all bared teeth and furrowed forehead and gleaming sweat and dishevelled hair, and you can hear how he endangers his precious voice to give it to you.

After encountering Kamarás, I was excited to dive into the newer, post-COVID productions of Elisabeth to see how the set design, camera work, character interpretations, and costuming had leapt ahead along with the changing decades.

They had not.

While the actors and musicians still give us their all, I observed that many recent German-language performances of Elisabeth employ basic set pieces more suited to a Scandinavian classroom than a beloved international production. Newer versions of the musical toned down the intimacy between the characters, undid the androgyny of Death by masculinising him, or even cut out a climatic kiss that takes place onstage (whilst leaving the heterosexual iteration of that same kiss undisturbed).

Though I still retain hopes of seeing Elisabeth live in Vienna one day, I realise with a cold stab of fear that perhaps its best German-language run really ended around 2006, and that there are not enough professionally shot versions of the musical to capture the breathtaking performances of all the myriad actors who flitted in and out of the supporting roles in those years. I hope to be proven wrong soon.

To end, let me say that I am filled with far more gratitude than what 2,500 words can express because Elisabeth and Kamarás have elevated my expectations to such a lonely, starlit height that I am now closer to Crown Prince Rudolf than myself: lost in my present and miserably waiting for better art, better romances, better politics, and a better future.

Funnily enough, Elisabeth includes a song, Die fröhliche Apokalypse, parodying people like me who do exactly this.

As I discover other productions of Elisabeth, though, I note that more than one Rudolf has graduated to take up the role of His Majesty Death, and in that transition I find untold solace and inspiration.

June 21, 2025

I thought parenthood would make you a pacifist

I was stupidly wrong.

I saw parents who fretted about the effects of screen time on their children’s minds seamlessly switch to calling for bombs to fall on the heads of children living on the other side of a non-existent border they would not be able to trace out on a map. This applies to India and Israel and Iran and Pakistan and Palestine and more.

I am not a particularly radical individual, and my political views are so bland that they are hardly worth taking the time or effort to publicise: corporations should not exploit customers or workers, digital development should not exclude the elderly, healthcare issues should be decided by doctors, religion should not hinder a child’s healthy participation in society, journalists should not be persecuted for asking questions, Generative AI use in media should be flagged, and bombs should not be dropped on the head of any baby, anywhere.

But the ideological ground under my feet has shifted so drastically that my bland views are now deemed to be radical, anti-national, traitorous, and shameful to share with (what feels like) a large majority of global society.

Bombs should not be dropped on anyone, but merely asking for them not to be dropped on a place containing a baby has become an act of political blasphemy, if not a form of career suicide for too many across the globe.

But anti-war beliefs are older than multiple nation-states today.

In 2018, I visited the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum and the Atomic Bomb Dome.

After my arrival at the museum, I slipped into the dark exhibition rooms and stared at cases filled with hair and clothes and personal belongings and even a human shadow on a wall that had been warped by the killing heat of the atomic bomb that the U.S. dropped on Japanese civilians on August 6, 1945.

Even amongst the survivors, innumerable life stories full of promise that were described on the museum’s bilingual poster boards or recorded via video logs were cut short by radiation-induced cancer, with many victims taking months, if not years, to die in excruciating pain.

I was deeply affected by a little wooden sandal I saw and photographed. This belonged to a school student named Miyoko and it still bears the imprint of the murdered child’s foot. The sandal strap was made out of a mother’s dress, which was how she recognised it as her child’s footwear. This was all she could find of her baby.

It is specifically this shoe I think of whenever I see anyone calling for a bomb to be dropped. Even today, the memory of that child’s big toe staining the wood of her sandal bars me from taking even a step closer towards anyone trying to convince others that wartime violence is a strategic necessity to stop more deaths or terrorism. These warmongers’ children come home safely in their own sandals, so their shoes remain happily abandoned and unloved on a household rack instead of becoming the most beloved proof of a vanished corpse, protected in a museum’s glass case.

I am writing all this to say that I thought there would be as many pacifists in the world as there are parents, but it is not so. The rest of us must remember wartime violence and resist its normalisation in whatever ways are possible for us.

Let a child’s shoe remain useless to the world.

All pictures captured by Sahana Venugopal

April 29, 2025

Pondicherry and the politics of woven cloth

Artists at work in Pondicherry | Google Pixel 6, 2025

Artists at work in Pondicherry | Google Pixel 6, 2025South India’s Pondicherry is not so much a city as it is a layering of French and Indian pastry sheets over a hot and humid filling of paradoxes and competing cultures, all greased by the residue of colonialism.

Bungalows and churches that witnessed the rise and fall of French India stand beside younger establishments called things like ‘De Fish Restaurant’ and ‘White Town Ice Cream.’ Some people know Pondicherry as a place to get cheap liquor or cars, and others know it as a place where you prove to multiple wary attendants outside the Mother’s Ashram that your phone is indeed switched completely off and not just silenced. While walking towards said Ashram in late April, we noticed a weaving factory where a white-haired woman in a sari was serenely sitting in the shade and spinning cotton thread on a charkha (wheel).

She encouraged us to take a look, so I invite you to step into an old world with me.

Sri Aurobindo Ashram Weaving Department

Sri Aurobindo Ashram Weaving DepartmentThe hall with a tin roof was the size of a large barn, filled with formidable wooden looms operated by hand while tubelights and unused fans were suspended from the ceilings.

The gentleman working at one of the looms was clearly taking a break on his phone, but when he saw there were curious outsiders (wearing blended fabrics) he very kindly resumed working without a word so we could stand next to him and gasp in awe at his efforts.

Handloom, rear view

Handloom, rear viewThe proprietor of the Sri Aurobindo Ashram Weaving Department was a senior woman who told me that the weaving centre had been in existence for 72 years, and that all the material was made here, with nothing coming in from outside.

Handloom, side-view

Handloom, side-viewThere were other staff members who worked through the relentless coastal heat as they cut stray threads and sewed the ends of fabric they were preparing to sell.

I found it was a solace to stand beside a handloom and watch a chequered blanket being birthed on the rack, not understanding how sheets of flawless geometric order emerged from such handmade disarray but witnessing it nonetheless.

A blanket being woven

A blanket being wovenFor buyers, there were hand-woven Turkey towels, blankets, and handkerchiefs folded in soft bundles and stored inside display cases lined with brown shelf paper and scented with naphthalene balls. The prices were a little higher than what you’d find in your usual cottonware stores, and rightly so.

A galaxy of cotton threads

A galaxy of cotton threadsFabric is inherently political, whether you are speaking about the Luddite struggle against mechanical cotton spinning machines, India’s own Swadeshi movement that popularised home-spun khadi cloth under imperialism, or Palestine’s instantly recognisable kufiya scarf that now symbolises resistance against Israel.

I find it fitting that all three of these fabrics were also used in the past to answer English tyranny in one form or the other.

But Pondicherry (and Auroville) aren’t exempt from criticism either. They too come to us with a turbid colonial legacy we need to discuss more publicly. Scholar Jessica Namakkal beautifully dissects this in her book Unsettling Utopia: The Making and Unmaking of French India, which I highly recommend to anyone visiting the area, even if you just plan to sit on the beach boulders with a croissant.

My (plastic-free) purchases from the Sri Aurobindo Weaving Department

My (plastic-free) purchases from the Sri Aurobindo Weaving DepartmentAll said and done, I returned to the Sri Aurobindo Weaving Department the very next day, and the proprietor was bemused as she totalled up my second order and watched me struggle to count out my coins. (They accept only cash.)

For me, it was a rare opportunity to see Indian artists working on a handloom in the merciless heat to arguably keep alive a thankless tradition that has clothed us and softened our homes across continents, for centuries.

In case you are interested, here is the website to see other fabrics from the Sri Aurobindo Ashram Weaving Department, which I believe would make lovelier presents than breakable gilt boxes and battered cartons of soggy sweets: https://www.sacso-online.com/product-category/weaving-department/

Permission was granted to take these photos.

This article is not an advertisement, a sponsored post, a collaboration, or a journalistic assignment.

December 9, 2024

Four translated novels that haunt me even today

Reading translated novels appears to be one way of proving to the world that the reader is inclusive, that they read diversely, that their outlook is all-encompassing, that they pick through the wastelands of literature to find hidden diamonds while more mainstream readers stand atop a mountain and catch whatever crap the Glorious Lord New York Times Bestseller List showers down on them.

But it is not so. Reading translated novels can be just as exclusive and restricting as sticking to your own language, because the literary canon of entire countries (namely, those in Africa and Oceania) is yet to be drawn on the English novel reader’s map, while even supposedly better translated nations do not always promote their most challenging or radical works. That being said, after two years of trying to read at least one translated novel from every country, I have found a few that follow me around like ghosts and have re-sculpted the way I think or speak about humanity. These are not necessarily my favourite titles, but more what I would suggest during this season to jaded readers who are consciously looking for something memorable and out of the ordinary. I selected these four books because they deal with the concept of being a foreigner, whether in a new university, an unknown island, a strange continent, or even someone else’s marriage.

Let’s begin.

Vita Nostra by Maryna and Serhiy Dyachenko; translated by Julia Meitov Hersey

“I don’t love him. I’m . . . we’re friends.”

“You are afraid for him. Love is not when you are aroused by someone, it’s when you are afraid for that person. ”

Rather than me telling you what this book is about, let me tell you what it did to me. It forced me up on winter mornings at 5 AM, made me lace up my running shoes, and had me running laps around the mist-shrouded local park where I panted and fought cramps as though my whole family would be slaughtered if I faltered. . .similar to the predicament of Vita Nostra’s unforgettable heroine Sasha Samokhina. Vita Nostra is a story about a seemingly ordinary girl who is forced to violate her own moral and bodily limits every day in order to survive her first year at a university that teaches its students to be something not quite human.

If you want a dark, Ukrainian saga that’s half university drama and half fairy-tale, written by a husband-and-wife duo and filled with incomprehensible lessons in sprawling classrooms, cruel mentors who use your most painful weaknesses against you, choked attempts at proving one’s love, and freezing gray evenings accompanied by black tea and bouillon cube soup while you mug up lessons that could rip away everything that you own, lose yourself in Vita Nostra and stare in awe at what you have become when you turn over the last page.

Friend: A Novel from North Korea by Paek Nam-nyong; translated by Immanuel Kim

Oh, you think ending a marriage is hard in India? It is, but now try getting a divorce in North Korea.

Rising singer Chae Sun-hee wants to leave her factory worker husband Lee Seok-chun, but in a dictator-ruled country where the family is considered an integral unit of the fabric of society, the unhappy couple and their child must endure a highly public investigation led by a traditional judge to see if a divorce is truly the best path forward for them and their wider community. The book is straight up North Korean propaganda, yes, and its patriarchal society points a finger straight at Sun-hee’s failure as a wife (much as Indians do) but the judge arrives at a startlingly different conclusion regarding why this marriage is failing. Then, of course, he tries to fix it.

Read Friend for its sense of place and to witness the values of a land you will never likely visit in your lifetime.

Ankomst by Gøhril Gabrielsen; translated by Deborah Dawkin

“How could a person find their way in this pitch-darkness? Head for the cabin with such certainty, precision? Who or what is actually out there?”

We land in Norway, where Ankomst’s protagonist, a researcher of climate conditions and their impact on seabirds, is content to spend crushingly long stretches of time as the sole human being on a merciless Arctic island besieged by storms and other unexplainable movements. While battling the trauma of her divorce and waiting for a reluctant new boyfriend to come and join her, she reads about the island’s past inhabitants: a once happy 19th century family that met with a terrible fate because of their isolation. As storms blow and birds build nests and the boyfriend comes up with yet another reason to avoid visiting her, the woman starts losing herself to the story of the destroyed family on the island before her. . .even at the risk of repeating their tragedy with her own body and mind.

Ankomst should be a tiring or challenging read; it largely takes place in the Arctic outdoors or its workaholic heroine’s mind that swings wildly between courage and chaos. But the writing and translation are stellar, so the novella becomes a thrilling single-afternoon read that veers further into horror with every page you turn, making you stop every few minutes to wonder how long your own isolation and sanity can co-exist before one kills the other.

Silence by Shūsaku Endō; translated by William Johnston

“Father, have you thought of the suffering you have inflicted on so many peasants just because of your dream, just because you want to impose your selfish dream upon Japan. Look! Blood is flowing again. The blood of those ignorant people is flowing again.”

Does a religion have a right to flourish in a foreign land? This is a question that worshipers, skeptics, and rulers have asked through the centuries and continue to demand today as they fearfully watch those around them drifting away from home and towards strange systems of faith.

In 17th century Japan, Christianity both saves and kills its most devoted followers. The very religion is smuggled into the country by European missionaries and is received with adoration by Japanese peasants who are oppressed by their homegrown caste system. But feudal rulers who want to cull the political influence of this faith force believers to stamp and spit on images of Christ, torturing to death their own countrymen who do not comply. Based on historical events, Silence follows a group of Portuguese Jesuit priests (and aspiring martyrs) who spirit their way into Japan to spread the teachings of Christ for as long as they can, while also trying to investigate the horrific rumour of a senior missionary who has seemingly left the fold to convert to Buddhism. The novel is pitiless as it brings out the never-ending storms that lash the heart of even the most staunch believer, who prays in the celestial forests and seas that only a higher force could have created, and tries to find proof of God’s love even through the unbearable bodily pain he allows them to endure.

November 1, 2024

My world tour in translated books

My childhood years were spent kneeling before a laptop, biting my nails and ruining my already atrocious eyesight as I devoured fan-translated scans of manga series, called Scanlations, that hadn’t been published in English yet.

To create these scanlations, unpaid ‘fan’ translators would scan thousands of pages of the manga, meticulously scrub out the original Japanese text in the speech bubbles, and input new translated text before re-uploading the pages online. Sometimes, in a badly rendered series, you could see a palimpsest of barely erased Japanese hiragana and Chinese kanji beneath the latest English-language text. Reading these online copies also meant that after every chapter, the poor Japanese-Chinese-English scanlators might hijack a few panels to tragically beg for volunteers to pitch in and help them translate the manga, or at least just clean up the scans for other translators.

Sometimes, there would be random birthday wishes passing between the translators. (Imagine seeing your favourite character being tortured to death by the villain at the end of a chapter, only for the next page to scream out HAPPY BIRTHDAY DARLING COOKIE-POOKIE CHAN!!!!!). Others would leave behind their grumblings, revelations, fan theories, annotations, linguistic musings, etc. in the narrative, much like the internet age reincarnation of medieval monks copying out an endless manuscript.

Here is a (partially censored) example, purely for academic understanding. Read it from right to left:

The process was a beautiful one, because these mostly Asian volunteers had a far better understanding of Japanese culture than an American or a British translator working at a mainstream publishing house, so by the time the licensed English-language versions rolled out a few years later, I had taught myself Japanese in frustration, which led me to see how poorly executed the Westernised versions were.

And this is how I started a love affair with translated literature.

As I slowly outgrew manga, I ran to translated literature in order to escape the MFA-style literary novels and fae folk romances that dominated the English-language bestsellers list. A few years and about 50 literary voyages later, here are the books that not only took me to their lands, but also drove splinters of their countries and people into my heart before snapping off the ends to make sure I would feel them forever.

You can find my ongoing reading list below without any more ado, or read on to better understand my approach and the tools I used.

list of translated novels I am readingAs far as possible, I tried to read a translated book by an author who was native to their country or region (meaning: not an illiterate white transplant writing about his sexual adventures with the non-white locals). My definition of the word ‘native’ also included refugees, immigrants, and second-generation writers. Whenever possible, though, I also tried to locate and read an English-language novel from the same country; this strategy worked well with India, Turkey, Palestine, and similar countries. You’ll see these titles in the list as well.

It does not fail to make me snort that finding and reading a translated novel that was originally snuck out of North Korea (Friend by Nam-nyong Paek) was easier than accessing translated literature from a number of African countries. This, I believe, eloquently captures the state of the mainstream English-language publishing industry today.

On the other end, numerous independent publishers are doing their best to uplift both international writers and translators. My favourite so far is Peirene Press, whose translated short novels and novellas are a perfect way to explore a new country and gobble up a book that perfectly fits into your evening.

Tilted Axis and Speaking Tiger Books are also great places to start looking for more international novels, apart from university presses (which are admittedly far too expensive).

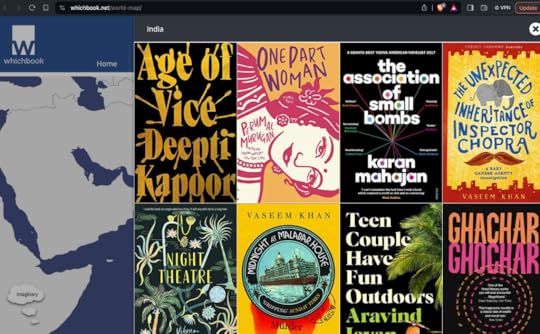

Furthermore, I love this tool from ‘Which Book’ that quite literally makes you travel the globe to explore a book list from every country, along with a short summary and some commentary for you to judge if the novel would be up your alley.

Credit: whichbook.net

Credit: whichbook.netIn my next post, I’ll actually share with you some translated novels that shook me, but for now, I hope you have what you need to start a world tour of your own.

On the other hand, if you are a more seasoned traveller than I am, please do share your own recommendations, and help me fill up the blank spaces in my reading list.

***

A Final Note

Though I would never consider myself in any way equal to the authors on these exalted reading lists, I just want to put it out there that I too have written a novel.

If you are ever travelling the world in books and want to sample something from India, please do consider giving my adult fantasy debut Body Traitor’s History a try!

find my book here

Cover image: Allegory for Translation – Gold flakes on black painted paper by S. Venugopal, 2024

September 13, 2024

Let us write an Indian literary novel together

After forcing myself to read a series of English-language novels by Indian authors, purely because they were called “literary” and were nominated for high-value awards, I have tried my best to learn from these masters in order to outline one such novel of my own.

(This is satire and no offence is meant to the authors or readers of such stories; I support anyone writing anything that puts food on their table in this economy.)

***

Study abroad. You cannot write an Indian literary novel unless you have a British/American university degree that can be referenced at every literary festival. Even better if this is a degree in creative writing. If such an achievement is not feasible, you can instead sneer at non-English writers from your country for a similar effect.

Start the story with a house. This is a historical mansion in the heart of an Indian village, or the leafier part of an Indian metropolis. It must have a godly Sanskrit name that is next to impossible to pronounce and conveys a sense of irony when contrasted with the ungodly shenanigans taking place inside.

You enter the house. Insert a small note referencing tropical heat, sweat, dust, flowers, cumin, garbage, stray dogs, and cobwebs.

The ancient patriarch (or the matriarch, if you want to be slightly different) has just died. Funeral rites are taking place. Priests are walking about, chanting. More Sanskrit. Fire and black smoke. Someone has tears running down their face. It is impossible to tell if this is due to the sorrow or the smoke, beautifully mingling the character’s inner and outer worlds.

There is a very disoriented NRI stumbling about the place, lost in cultural shock. They really just want to fly back to their home in the U.S./UK/Australia/any country where white people form the majority.

Though the story takes place in the 21st century, it is the 16th century for the people working within the house. The maids exist to be screamed at by the lady of the household, or harassed by the males.

The dead patriarch/matriarch’s spouse is coughing or sleeping in a bedroom upstairs that smells like camphor. Load the next funeral.

Another old person in the house is losing their memory and will later have a very theatrical breakdown during the most public moment possible. This is not so much about the person’s intimate health struggle as it is a metaphor for India losing sight of its past and being carried away by modernity.

Cue passionate discussions about selling the house and turning it into a block of flats, because the patriarch/matriarch is dead. This is a metaphor for India’s development.

One couple in the family is on the brink of divorce and trying desperately to hide this from the elders.

Some drama about the family jewels, property disputes, inheritances, and a slimy real estate agent who comes to look at the house.

Someone’s mother runs away because they cannot deal with the patriarchal household. The children are left with lifelong abandonment issues and a father who does not know how to cook.

A chain-smoking modern woman and her severely overworked husband are wondering why they are unable to conceive a baby, wondering if perhaps the gods don’t want them to be parents. This is a metaphor for India having nothing for its youth to inherit.

Shocking objectification and dehumanisation of working class men and women within the divinely named mansion.

A rich daughter and her mother have a fight about the way she was raised, showcasing India’s generational differences and the effects of social mobility on traditional gender roles. A slap is thrown in. The women finally realise there is more that unites them than divides them.

The city is changing for the worse. (More people are getting human rights and building homes.)

The trauma of riding an Indian bus, courtesy of the NRI who provides comic relief.

One of the domestic workers in the house, or their child, is the illegitimate heir of the patriarch/matriarch who has just died.

Cooking scene. Something vegetarian is being made with cumin, chilli powder, and turmeric.

An old woman is coughing and recalling the past. Again representing India.

Sexual crimes take place, purely for shock value. The victim’s trauma will be forgotten by the author half a page later. Some incest is added to lift the sagging mid-section of the book.

A long debate on the pros and cons of divorce. The debate ends when the family’s most repressed ancient lady stands up and vocally supports the young wife who wants the divorce. The family’s men are stunned into silence. The generational gap is thus successfully closed.

The person who is losing their memory starts having visions and revealing the family’s scandals. The domestic worker or their child’s true parentage is revealed here.

A rich person in the house is unhappily romancing (read: harassing) their working class employee who can’t say no, because they really need this job.

An affluent, unemployed woman looks out at her sweating and suffering domestic workers, wondering if their lives are happier than hers because they are poor and thus have fewer things to worry about.

A religious riot takes place. A minor character you can barely remember is assaulted or killed.

The house slowly empties again as everyone returns to their individual residences. If the house is sold, it means the author is pessimistic about India’s future. If the house is kept within the family, it means the author is pessimistic about India’s future.

Once your literary novel is published, it will be long-listed for a literary prize sponsored by an international corporation that enables fascism and destruction through its products. During the awards ceremony, you will subtly hint at the importance of forging bonds, building communities, and ending wars.

***

Jokes aside, I do think the literary novel – when written well – has an undeniable role to play in holding up a mirror to the ugliness of Indian society, and the resilience of its most marginalised members.

Here are some of my favourites that defy inferior tropes and break the bars of their genre to release a story into our world that is both crucial and gorgeously composed.

When I Hit You by Meena Kandasamy: A heartrending work of auto-fiction that dissects one woman’s journey through love, survival, politics, and creative writing as she leaves an abusive marriage.Cobalt Blue by Sachin Kundalkar/Translated by Jerry Pinto: A lush yet unsettling multiple-POV novel about an orthodox Brahmin family in Maharashtra that invites a paying guest into their home – only for two siblings to lose their hearts to him.History’s Angel by Anjum Hasan: The poignant, ridiculous story of a history teacher who plumbs the ocean of his knowledge to comfort himself as he is harassed both publicly and privately for being a Muslim.Hangwoman by K.R. Meera/ Translated by J. Devika: In a carnivalesque coming-of-age novel, a young woman in the most dysfunctional family to ever exist is forced to participate in a media circus and define what female empowerment means to her, as she prepares to execute a prisoner on death row.Cover image by Sahana Venugopal

September 8, 2024

On stabbing out eyes and professional workplace conduct

One advantage of pursuing your higher education while your former uni classmates join the workforce is receiving their steaming hot gossip and the life lessons within, like a baked bun with a chocolate cream core that is relished by only the most out-of-work listeners (such as myself).

When my friends complained about their jobs, I noticed a common villain in their stories: a manipulative senior or self-styled mentor who exerts their authority over the new employees in the manager’s absence, ordering them to complete those dirtier assignments with a lower chance of praise and a higher risk of failure. If the venture is successful, they net all the credit. If it sinks, they steer neatly away from the storm and let their junior face the department’s wrath.

I nodded sympathetically as my fuming friends consoled themselves with alcohol and cursed at capitalism.

But soon enough, I met a man from almost 500 years ago who found himself confronting a similar situation at work. Except, this man wasn’t being urged to launch a tricky new product feature or plan the office holiday party.

In the 16th century, Aly Dūst was a servant of the Mughal Emperor Humayun, and was resisting a colleague who wanted him to blind the emperor’s brother. This did not mean dazzling the man with a quarterly plunder report, per se, but actually using some needles to put his traitorous eyes out of business. (Today, one can argue this practice has been replaced by the non-compete clause.)

I am no historian, but according to the Mughal-era narrator of the incident and my personal understanding of the text, Aly Dūst boldly pointed out that his co-worker refused to cough up even small(?) cash sums without Humayun’s explicit permission but was seemingly happy to let a subordinate chop up royal eyeballs without double-checking with their boss.

Here is how the scuffle went, according to the long-suffering narrator who clearly just wanted to clock out for the day:

Early in the morning the King marched towards Hindistan, but before his departure determined that the Prince should be blinded, and gave orders accordingly, but the attendants on the Prince disputed among themselves who was to perform the cruel act. Sultan Aly, the paymaster, ordered Aly Dūst to do it; the other replied, “you will not pay a Shāh Rukhy (3s. 6d.) to any person without the King’s directions; therefore, why should I commit this deed without a personal order from his Majesty? perhaps to-morrow the King may say, ‘why did you put out the eyes of my brother? what an- swer could I give? depend upon it I will not do it by your order.” Thus they continued to quarrel for some time; at length, I said, “I will go and inform the King.” On which I, with two others, galloped after his Majesty: when we came up with him, Aly Dūst said, in the Jagtay Tūrky language, ” no one will perform the business.” The King replied in the same language, abused him, and said, “why don’t you do it yourself?”

While my 21st century friends were thinking about performance reviews rather than plucking out eyes, I believe Aly Dūst makes a fine argument here: it is better to be verbally abused because you have an eye for detail (forgive me) than to be questioned for overstepping your limits as an employee. At the same time, however, it can be argued that a leader wants their subordinate to show some initiative. So what does a faithful servant do? Put out the emperor’s brother’s eyes and take their chances? Gallop after the emperor and ask him to reassign the eye-plucking task? Maybe put out just one eye and see if the emperor is feeling merciful enough to leave the other one?

After chewing on this dilemma for some time, I point my finger straight at the emperor Humayun, and his utter failure as a leader. One cannot throw an unpleasant task into the air—”Poke out my brother’s eyes before we touch base next time”/”Arrange the office’s Secret Santa party”/”Chase that dinosaur-sized gecko out from behind the toilet”—and run off into the sunrise, expecting a random person in the vicinity to see it through. No, reader, you have to name your victim or even better, make them finish the job while you watch, no matter how reluctantly. In this case, the scapegoat was poor Aly Dūst, who made the mistake of approaching the emperor for some clarification.

Now, I shall step aside and let you witness the rest of this incident.

After receiving this command, we returned to the Prince, and Ghulam Aly represented to him in a respectful and a condoling manner that he had received positive orders to blind him; the Prince replied, “I would rather you would at once kill me;” Ghulam Aly said, ” we dare not exceed our orders:” he then twisted a handkerchief up as a ball for thrusting into the mouth, and he with the Ferash seizing the Prince by the hands, pulled him out of the tent, laid him down and thrust a lancet (Neshter) into his eyes (such was the will of God). This they repeated at least fifty times; but he bore the torture in a manly manner, and did not utter a single groan, except when one of the men who was sitting on his knees pressed him; he then said, “why do you sit upon my knees? what is the use of adding to my pain?” This was all he said, and acted with great courage, till they squeezed some (lemon) juice and salt into the sockets of his eyes; he then could not forbear, and called out, ” O Lord, O Lord, my God, whatever sins I may have committed have been amply punished in this world, have compassion on me in the next.”*

After this darkly comical incident, there comes a footnote that makes me snort in disbelief every time I read it.

* The usual mode of blinding Princes was, by passing a hot Myl (needle or bodkin) over the pupil of the eye, which did not give much pain.

All said and done, I understand now the proliferation of Mughal treatises whose authors reference alcohol or opium more frequently than their own children.

If you enjoyed that little episode, I’ll have you know this tainted sense of workplace comedy was something I tried hard to capture in my own novel, Body Traitor’s History, which I wrote, edited, and self-published this summer. You can find my book here:

Paperback linke-book link

Thank you for your time and attention!

Source for the historical text

Excerpted from Jawhar, F., & Stewart, C. (1832). The Tezkereh al vakiāt, or, Private memoirs of the Moghul Emperor Humāyūn.

Cover image by Sahana Venugopal

August 25, 2024

Chennai Photo Walk: George Town’s flower merchants on black & white film

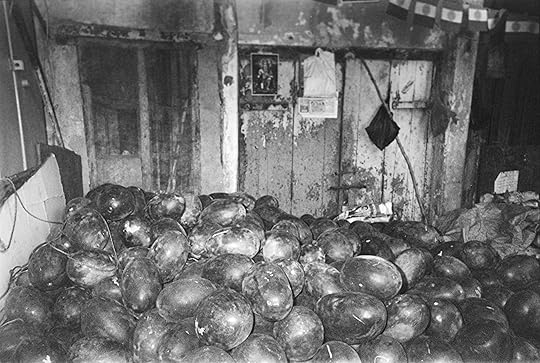

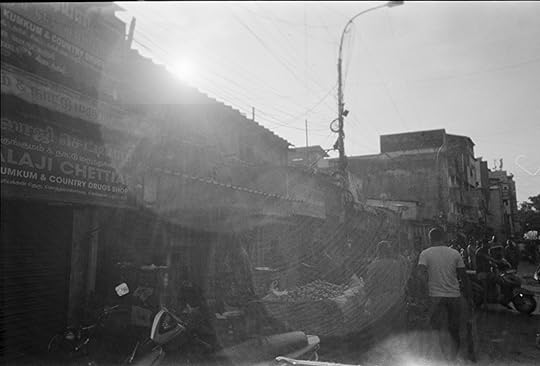

George Town, Chennai, shot on CPB ReSpool | K100 | 35mm Black & White Film [Expired]

George Town, Chennai, shot on CPB ReSpool | K100 | 35mm Black & White Film [Expired] A few weeks ago, I took a charming photo of a group of grey-haired seniors on my phone.

As I was smiling at the image, contemplating the elders’ sweet cauliflower faces and the lifetimes of wisdom in their wrinkles, a notification popped up. My Google Pixel 6 had a suggestion to improve the image I had shot.

Remove people in the background?

Anyway, that’s why you’ll find me muttering under my breath as I stuff a roll of 35mm film into a dusty analogue camera; you won’t see one of those things eagerly offering to kill off the people in your photo just yet.

***

Early this summer, I found myself joining an early morning film photo walk in North Chennai hosted by the Chennai Photo Biennale Foundation. Between the halogen lamps of the flower merchants and the alleyways filled with the previous night’s rain, I was charmingly scolded by a local businessman for not having enough followers online to appreciate the photo I was taking of him with his mountains of pink roses. (My Instagram account had less than 15 followers at the time and I had assured him I was certainly not an influencer.) To get more people to see my work, he told me I had to show my “திறமை” [Thiramai], which I translated as ‘capacity’ or ‘ability’ at the time. However, Google came up with the far more concise ‘skill.’

This discrepancy makes sense, because I do not think of myself as a “skilled” film photographer. I am simply one who has the “ability” to take photos. Either way, though, the flower merchant’s advice was sound and so here we are.

Since I was using a borrowed budget film camera and expired 100 ISO film at 6 AM, this is nowhere near my best work. Even so, I will showcase my ability and invite you to decide whether there is any skill to speak of.

Camera: Kodak KB10 lent out by CPBFilm: CPB ReSpool | K100 | 35mm Black & White Film [Expired]Development: CPB DarkroomLocation: George Town, ChennaiClick or tap on the photos for a closer look.

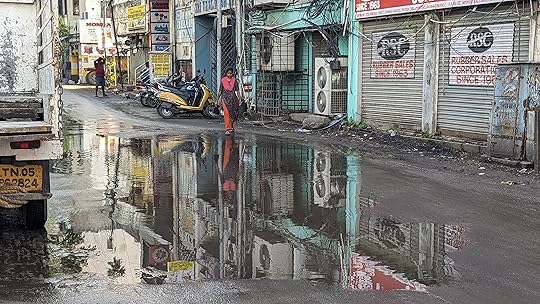

Despite my earlier complaints, I took some photos on my Google Pixel 6 after all.

Here they are, with just some minor edits for sizing and colour:

August 12, 2024

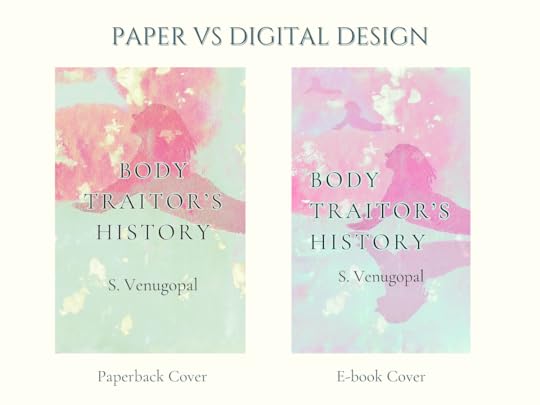

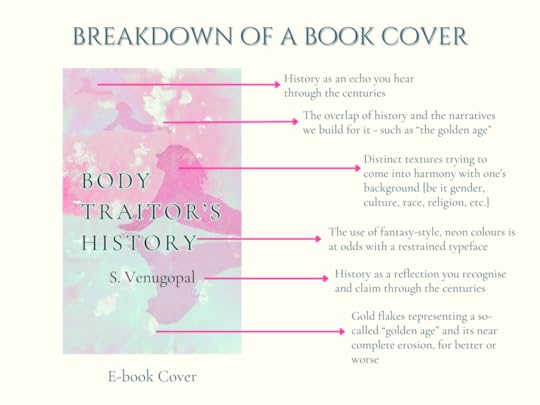

Creating my fantasy novel cover: Mughal influences and breaking the “Golden Age”

They say everyone needs a hobby, but I think what a person really needs is an obscenely personal project they can squat over in the manner of Saturn Devouring His Son, horrified by the the carnage they cannot stop but also relishing the all-consuming control they have over the masterpiece, or the destruction, clenched in their hands.

My fantasy novel, Body Traitor’s History, served as that instrument for me during the pandemic years, when I researched, drafted, edited, proofread, and formatted the manuscript for both print and digital distribution.

Then, I created the cover.

Why I decided to go down that route (and my general disillusionment with mainstream publishing) deserves another post of its own, but here, I constrain myself to notes on design, inspiration, and technique.

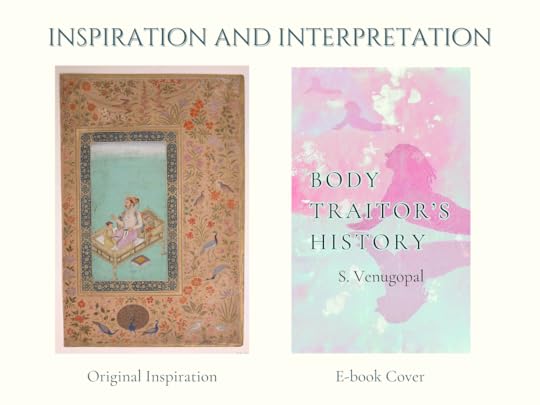

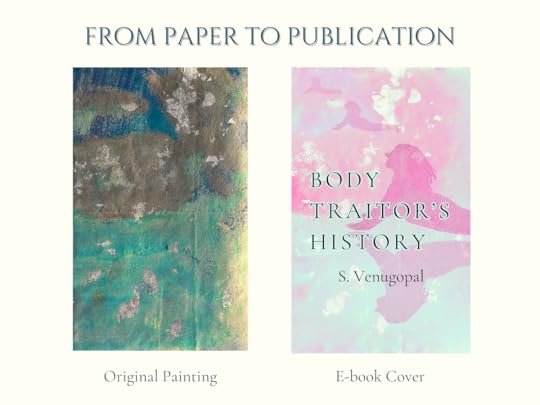

Since Body Traitor’s History is a novel inspired by India’s Mughal history and its legacy, I wanted to playfully insert some elements of Mughal painting in my own work.

To me, this included flattened subjects (a neat way of evading my struggles with perspective), the liberal use of gold detailing, transparent colours, translucent textures, and human figures caught mid-action.

This isn’t as far-fetched an idea as it sounds; nearly every Indian high-school art class worth its salt will at some point see students forced to replicate Mughal miniatures. My own painting of Empress Noor Jahan lives facedown in a dark loft with the household lizards, to spare the seeing public.

As an adult, however, I was entranced by a painting of a younger Emperor Shah Jahan with his son, Prince Dara Shukoh. The mint green background contrasting with the light purple fabric, the feverish use of gold lines, and the smaller human figures on the large cushion mesmerised me. (In case you are curious, the black stains under the emperor’s arms are because of the perfume he is using.)

“The Emperor Shah Jahan with his Son Dara Shikoh”, Folio from the Shah Jahan | Album Painting by Nanha; Calligrapher Mir ‘Ali Haravi, via metmuseum.org

“The Emperor Shah Jahan with his Son Dara Shikoh”, Folio from the Shah Jahan | Album Painting by Nanha; Calligrapher Mir ‘Ali Haravi, via metmuseum.orgAfter months of experimentation and countless failed paintings, I finally landed on a workable base, achieved by randomly layering dark blue ink and copper and gold paint on a sheet of Chinese rice paper given to me by a penpal. Rice paper is extremely fragile and reacts almost violently to moisture, but is able to hold many more layers of pigment than your standard sheet of watercolour paper.

While the surface was still wet, I added gold flakes in no particular order or arrangement. As I scanned the original design to begin the digital edits, there was a light burn that you can see on the right hand column of the original piece.

Using Adobe Lightroom on mobile (hey, it was free), I changed the colour tones until I achieved the mint green and pink/purple combination I was gunning for, while working to keep the gold flakes luminous.

Regarding the human figure, I went for a recognisable yoga pose. Called the Cobra Pose in English, it shows a person (incorrectly) rising from a face-down position on the floor. I’ll leave the symbolism of it to you.

The figure in the image, which many believe to be the main character or the narrator, is actually me. I used a photo of myself, enlarged it on a screen, and traced it, thus again trying to avoid the pitfalls of freehand anatomical proportions. I transferred this tracing to a thick sheet of watercolour paper and made it into a paper doll of sorts, which I then scanned and slapped onto the original image in the style of a collage.

Due to how colours are processed, as well as differences in dimensions, the print and digital versions of the book have slightly different covers. I like the warmer green and pink combination on the paperback, but I feel that the digital version preserved the shimmer of the gold flakes and gave me more space to play with the paper cut-outs.

And finally, the meaning of it all.

The overarching theme of Body Traitor’s History is, to me, the truth of what we so carelessly call a “golden age.” Shah Jahan’s time is referred to as one, and while it might have been a golden age for Dara Shukoh during his childhood, one can hardly say the same for the people who died from septic wounds, malnutrition, slavery, parturition, or wartime atrocities.

Historians of a more religious or nationalist bent these days rudely demand that we agree with their evaluation of which ages were golden. Every hour, they stupidly eulogise worlds without Tylenol and Tiger Balm and labour laws and Wi-Fi that their own spoiled children would have not survived, but perhaps they have a point. After all, every age is gold for those who have the most of it.

The histories of those without gold, meanwhile, are defaced and replaced with more striking characters.

An unused cover design concept for my novel that I may one day resurrect [screenshot taken from the Canva workspace]

An unused cover design concept for my novel that I may one day resurrect [screenshot taken from the Canva workspace]Body Traitor’s History tries to address this question in good faith and, most importantly, with love. So if you’d like to give it a try here, I’d be very grateful.

paperbackE-bookJuly 26, 2024

Meet My 35mm “Friends” | Part 2

Fuji Velvia 50 film strips, held up to sunlight | Shot on a smartphone

Fuji Velvia 50 film strips, held up to sunlight | Shot on a smartphoneUnlike veterans of film photography who compose epic poems in praise of their art, I struggle to defend this hobby. (I struggle to defend almost anything, but that’s for another day.) Basic 35mm film is overpriced and persnickety, with more brands going extinct by the day. Developing photos involves money, gelatin, and huge volumes of chemically contaminated water. Next, consider that out of a roll of 36 shots, maybe five will satisfy me. Despite what the fanatics say, film is dying as it’s rapidly usurped by analogue photography apps and editing software, and perhaps that’s not a tragedy.

At the same time, I’m not ready to forever sacrifice real light leaks for Lightroom presets.

With that out of the way, let’s go meet this group of charismatic yet problematic players.

You see this creature on the campus of a school that caters to upper middle class children. They are well over 40 but insist on dressing just like the high school offspring they’ve come to pick up. There is an abundance of neon pink chiffon or thrombosis-inducing jeans. Their makeup comes from duty-free shops in Dubai or Paris, with colors that bite the skin to bring out its beauty. Or they drive a scarlet luxury car with an open roof, blasting the horn and air-conditioning so everyone can envy their children as they clamber into the leather interiors with muddy shoes. You are chatting with another parent when they approach. They give you a tight-lipped smile, then invite your friend to Sunday brunch.

Ashikaga Flower Park | Shot with Pentax Zoom 105-R | [2018]

Ashikaga Flower Park | Shot with Pentax Zoom 105-R | [2018]Velvia 50 makes the Ektar 100 look like a sweet-natured Marxist; every shot I took with it felt like a minor crime. No amount of light seems to be enough for this color reversal film but when you satisfy its tall list of needs, Velvia 50 pays back the favor with pinks and reds that run as rich as blood, and grain almost as fine.

Hitachi Seaside Park | Shot with Pentax Zoom 105-R | [2018]

Hitachi Seaside Park | Shot with Pentax Zoom 105-R | [2018]Velvia 50 also does a fantastic job of differentiating between shades of blue. The contrasts are robust without feeling digital, and the degree of saturation would have probably made a Fauvist weep in joy. The film’s noticeable vignette gives almost all its photos the look of a storybook postcard. Whites are subtle but the shadows can be merciless.

UNU Farmer’s Market | Shot with Pentax Zoom 105-R | [2018]

UNU Farmer’s Market | Shot with Pentax Zoom 105-R | [2018]This is an immersive film in every sense of the word; its dark margins lock in a scene whose almost sentient colors command your attention.

Velvia 50 is here to seduce your jaded eyes. . . but only if you play on its level.

2] Japan Camera Hunter Streetpan [ISO 400]

Dark isn’t always deep. You thought you might gain a new philosophy by spending time with them but instead all your clothes smell like old cigarettes and you’ve lost your immunity. They declare their organization will be featured in the world’s newspapers, yet can’t get out of bed before 1pm. They curse the USA and teach you about neo-imperialism, then apply to Cornell. They sit in rooms without turning on the lights and drink more Diet Coke than water to prove they have trauma. They’ll be friends with anyone, but are somehow attracted to only one racial type.

Shinjuku ni-chome | Shot with Pentax Zoom 105-R | [2018]

Shinjuku ni-chome | Shot with Pentax Zoom 105-R | [2018]With JCH Streetpan, I was in the rare position of being able to witness a new 35mm film hit the market. In reviews and sample photos, I noted the sticky blacks and brave levels of contrast. Streetpan was uncouth, grungy, and loaded with smoky roadside drama. 22-year-old me fell in love.

The versatility of this film is impressive, no doubt, and one has to pull together a search expedition to find any grain (when you shoot it right). I read that JCH Streetpan was meant to be used in low light urban scenes/infrared photography, and it got me some atmospheric urban nightscapes. For that, I’m thankful.

But at the end of the day, I had mixed feelings.

Uji and Osaka | Shot with Pentax Zoom 105-R | [2018][image error][image error]

Uji and Osaka | Shot with Pentax Zoom 105-R | [2018][image error][image error]When unsure, the film overcompensates with black and is prone to muddiness; take a spontaneous shot late in the afternoon and you have a photo which looks like it was washed with espresso. Meanwhile, whites are stripped of all texture and flattened out, so I wouldn’t recommend it for portraits.

With every picture, JCH Streetpan lets you know that it deserves to be in a far more expensive camera, in the hands of a far more experienced shooter. One factor may have been the way Streetpan was developed in the lab, considering its novelty at the time.

In conclusion, this film tries to accomplish many things. I wish accessibility had been one.

3] Lomochrome Purple [ISO 100 – 400]

B(e)ad jewelry. Unbrushed hair. Weed. Orientalism.

Your friend believes they are the universe itself, but can really be summed up in these words. They’ve learned to repackage a musty world and sell that distortion to us commoners, whose deepest journey into our soul was trying to remember when we last exercised. They promote capitalism, but call themselves “gy*sy” or “baby witch.” They tell you that your migraine is the result of a war within your soul and that your vaccine is made of fetal tissue.

Aftermath of a snow storm [2018]

Aftermath of a snow storm [2018]Lomochrome Purple is a piece of marketing genius. Take something that’s already niche and add yet more ways to be niche and effectively keep your fanbase from outgrowing you. This film is a revival of the more traditional (yet sadly extinct) color infrared films of the past. I can see this being a source of attraction to new film photographers who don’t care much for professional color films, and need something more flamboyant to sustain their interest in the medium.

An added advantage: very few self-absorbed monochromatic street photographers (male) would be caught dead with this counterculture plaything. You can buy Lomochrome Purple as only film, or as part of a reusable disposable camera.

Mt Fuji sunset from Enoshima [2018]

Mt Fuji sunset from Enoshima [2018]In terms of contrast, the colors do most of the work. The dominant shades are cyan, a range of raisin, and dulled pinks/reds. If you use color gels, change the exposure time or camera ISO, or capture scenes with high amounts of diffused light, you get cleaner purples and pinks than what I have here, along with undertones of green and/or gold highlights. I realize that’s too random to be of much help, but I suppose that’s exactly what Lomography was hoping for.

Expect a lot of grain and dark patches for no discernible reason. Recommended for photographers who chase after cooler shades and aren’t afraid to admit a love for fantasy and/or hippie culture.

All in all, this is a film for that motley group of world-builders playing in narratives rather than facts.

Welcome to your first creative writing workshop! You glimpse this student seated next to the professor and size up your competition. They’re wealthy and cosmopolitan in a subtle way and seem as deep as a children’s swimming pool. You quickly dismiss them; such people will never experience a trauma worth exploiting for the sake of a publishing advance.

At the end of the semester, their story – a stream of consciousness style family saga about surviving PTSD – goes into a literary journal. Yours goes into the non-recyclable trash.

You learn that privilege doesn’t always signal a lack of talent, just as suffering doesn’t guarantee its presence.

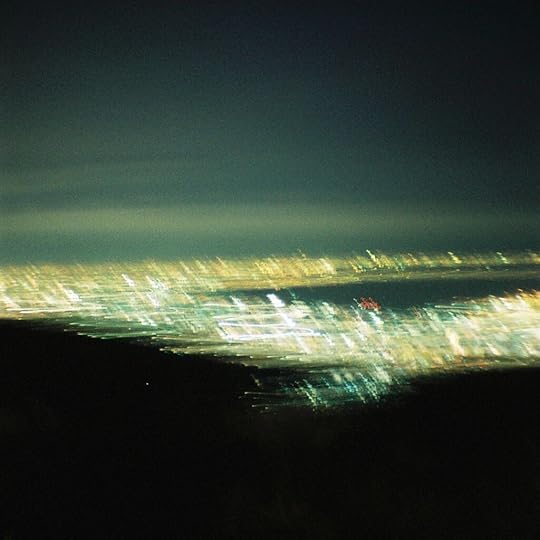

Advent of night traffic | Shot with Diana Mini | 2018

Advent of night traffic | Shot with Diana Mini | 2018My relationship with Fuji Natura 1600 was like an ignorant encounter with something from the spirit world. If I had known the film stock was only available in Japan and was soon to be discontinued, I might have treated it with a little more dignity and shot some human subjects, rather than trying out long-exposure night traffic photography.

Add to that a toy camera with a love of randomly dropping solar flares over the photos, one police officer who kept following me because he thought I was trying to throw myself off the traffic bridge, and my cold, numb fingers failing to advance the film spool. The result? A rave on an alien planet.

Multiple counts of urban exposure | Shot with Diana Mini | [2018]

Multiple counts of urban exposure | Shot with Diana Mini | [2018]From what little I can see in these photos, Natura 1600 does a fine job with various shades of the same color and delivers bold highlights as well. The black is clouded with green (more due to light pollution than the film), but under the right circumstances you can also get a pure color. I also love the high contrast and flattened grain.

But the 1600 ISO proves itself in the way so many of the fine details (stained clouds, electric poles, tree branches, etc.) are saved and allowed to keep their definition against a dark background, rather than just being blended in.

If you ever stumble across this film, guard it with your life and immortalize your nocturnal escapades.

They enter the office at 8:50 and rise from the chair at 17:10. They vote for (right of) centre parties and attend classical music concerts in their private box. They arrange college funds for their communist children who refuse to bathe, and bring the family to first world cities during the holidays. Strangely, their smiles go missing: the all too common fate of the one who captures portraits of others. Most media they consume was released in the 1970s, and they use a notebook to budget their finances. Friends envy their wine cellar.

Long after the communist children fail in their creative ventures and surrender to capitalism, their parent will pay the $10,000 fee and climb Mt Everest.

A China Town in Japan | Shot with Diana Mini [2018]

A China Town in Japan | Shot with Diana Mini [2018]Kodak Portra 800 is a film that demands to be treated with reverence. It’s generally used to capture studio portraits of eclectic-looking people who scowl at the photographer or turn away with artistic coyness. It’s a vivid yet balanced film that brings out the magic of forgettable features.

This film is a well rounded player in the color department and drinks in every shade with greed. I’m quite appreciative of that blue tinge that keeps the skin tones from becoming too yellow, yet preserves the warmth of a scene.

[image error][image error]Don’t let the name or the price fool you. You may think Portra 800 is a high-end professional color film that must be treated like a queen, but it can also be a creature of the night – a predator happy to follow its subjects through the studio and the cemetery.

Chatting with a Jizo in Oku-no-in | Shot with Diana Mini | [2018]

Chatting with a Jizo in Oku-no-in | Shot with Diana Mini | [2018]The above photo of a Japanese deity was shot close to midnight in a gloomy Buddhist mausoleum where the air was heavy with snowy vapor. The only source of light was my toy camera’s flash and a few weak bulbs behind me. Yet the detail on the god’s face, complete with stone contours and a glassy sheen, is nothing short of formidable.

The range of brown hues pulled from the tree on the right gives you an idea of what this film can truly accomplish when capturing human skin.

The grain in these photos looks intense, but it’ll smoothen out if you shoot on any device that’s even a half-step above my own. I was unfortunately too broke to buy the film again to try it out on my point-and-shoot camera.

My closing notes? If you love someone and want to spend the rest of your life with them, but find yourself too repressed to speak the words, take a picture of them with Portra 800 instead.

Impressions of Kobe, seen from Mt Rokko | Long exposure shot with Diana Mini | [2018]

Impressions of Kobe, seen from Mt Rokko | Long exposure shot with Diana Mini | [2018]No more is needed.