Paul Alkazraji's Blog - Posts Tagged "athens"

A story of love and adventure in ancient Greece

Pic. P. Wilson

Interview with Dan Truitt, author of ‘Spartan’s Daughter’.

By Paul Alkazraji, author of The Silencer

Tell us a little about yourself.

My full name is Daniel Perry Truitt. My maternal grandfather was a Greek immigrant to the US named Periandros Harbelis, or Perry for short. I was born in 1954 and raised in the Chicago suburbs. I grew up Catholic, became an atheist and a hippie around 1970, and then became a Christian in 1984 after studying the book of Acts. That was while simultaneously following Anthony Hopkins in a little-known role of his as St. Paul in Peter and Paul, a teleplay broadcast during Holy Week 1984. Shortly after that, I determined that I had been called to Greece. My best friend in the US jokes that I “came to Greece to give the Greeks the Bible in their own language.”

Tell us about your new book.

Spartan’s Daughter is the story of a nineteen year-old girl who leaves Sparta, her native city-state, because her options there as a woman are limited. According to Spartan tradition, she must submit in marriage to the first man who can successfully ‘kidnap’ her! So she travels only at night, by foot, to Athens, where she has a great-uncle who will look after her. She doesn’t know that he is seriously ill and will be dead by the time she arrives. It’s the first of September, 490 BC. On the ninth of September, the battle of Marathon will be fought. She’ll be the only Spartan, and the only woman, to participate, albeit in a very small but very crucial way. Spartan’s Daughter is primarily a love story, with some adventure, a little violence, and some history thrown in.

Is there an aspect of it you are particularly pleased with?

One thing that turned out in a way I really liked and didn’t expect was the way the characters talked and acted. I’ve been in Greece nearly 25 years and I know how Greeks think and act, and why. It was easy transferring those behaviour patterns to 490 BC. After all, Greece has one of the longest unbroken cultural lines in world history. I actually got this idea from Woody Allen, in his movie Mighty Aphrodite. He opens the film with a classical face mask-wearing Greek chorus and narrator, but in the background he’s playing modern bouzouki music. I thought that was really clever.

Share with us a sentence of your choice from it.

This one illustrates the way I have Greeks thinking about their gods. Morpheus is the god of dreams. Kalliope, the main character, is dreaming. She knows that Morpheus is the man running the projector of her dreams:

“To Kalliope, Morpheus was rather like an insane but brilliant artist who was constantly coming up with bizarre situations and pictures which no one else possibly could.”

Tell us about something you like or dislike in one of your characters.

Something I like: I have the male protagonist, an Athenian mercenary named Alexandros, not be flawlessly handsome. He would be so were it not for a deep, nasty scar running from his eyebrow down through the bridge of his nose from an opponents’ sword. In moments of distress his hand goes to this scar and touches it.

Fiction writers put characters in dramatic situations ultimately to ‘say’ something. What are you saying in your latest work?

I don’t like Christian fiction in most of its modern forms. By the same token there is great need for Christian verities (true principles) to be subtly taught in the arts the same way godless atheism is. So this is an attempt to do this. I’m talking about those like physical and moral courage, sexual fidelity, and a love of the freedom our Creator gave us to be who we are. But even then I tried to tone it down a little and make this primarily a love/adventure story. I can’t stand didactic fiction, which is my main problem with Christian fiction. The only Christian novel I would give to a non-believer is Francine Rivers’s Redeeming Love, which is a beautiful 19th century take on the prophet Hosea and his unfaithful prostitute wife.

How does your faith influence your writing?

I’ve understood that God gave me storytelling and descriptive abilities to help people grasp what existence is all about. Our goal as Christians is to ultimately bring glory to our Maker. There is absolutely no point to my writing a single sentence if Biblical values do not percolate through it.

What aspect of the craft of writing do you find most enjoyable?

Watching a first draft unfold. It’s a blast, as long as you know how things will end. A second enjoyable thing is just playing with my imagination, watching two disparate ideas collide and create the germ of a story.

What books or authors do you like to read?

I love my Kindle. I just counted eighteen books that I’m reading on it right now. The last couple of years I like history and biography more and more. A good biography will have me visualizing a person, time and place pretty vividly. It’s like taking a trip in a time machine. Favourites include James Lee Burke, Stephen King, John Grisham, Flannery O’Conner, Michael Connelly, William Faulkner, Andrew Klavan, JRR Tolkien, David McCullough, and Shelby Foote. Five of those are from the American south, BTW.

Tell us about something you’ve read recently that moved you.

That’s probably a history of the American Dust Bowl in the 1930’s called ‘The Worst Hard Time’... absolutely unbelievable suffering. It changed my politics. People then had no social safety net whatsoever, and were left alone to sink or swim on their own. The other side of that coin is that the farmers in Oklahoma and the Texas Panhandle created the Dust Bowl by over-ploughing the prairie and expecting a couple decades of unusually rainy weather to continue indefinitely. They got greedy, especially with wheat prices going through the roof because of WWI. At any rate, for most of us that safety net is in place as a refuge of last resort.

What are you most thankful for in life?

Eternal life of course.

What makes you laugh?

People falling down... I’m laughing now just thinking of it.

***

Dan Truitt has written four novels during the last ten years. His novel Spartan’s Daughter is available to read and download here.

http://turnerjunction.blogspot.al/

Published on November 14, 2013 09:53

•

Tags:

athens, christian, greece, james-lee-burke, marathon, morpheus, sparta, thessaloniki, woody-allen

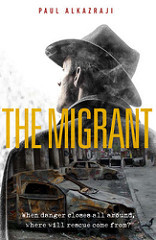

'The Migrant' to be published soon...

Some good news to share… I’m very happy to say that I just signed with a UK publisher for the novel I’ve been working on for a couple of years now – and finished, well, more or less. All being well, that should be out early next year. Hurray! (The photo is of me doing research for the story in Athens two years ago – well, pretending to read a Greek newspaper actually :) )

Early draft blurb for 'The Migrant' (working title).

‘No one has heard from Alban since he set off through the Albanian mountains to seek work illegally in Greece. Pastor Jude Kilburn is growing increasingly concerned. Could something have happened to the youth on route in the border forests? Could he remain safe in the Athens underworld if that was where he’d gone?

As the anti-austerity riots of 2012 explode, and the populist ‘Neo-Hellenic Front’ marches through the Greek capital, Jude gathers the help of two incompatible friends and sets off to find Alban. With him are Albanian Secret Service man Luan Gurbardhi, and reformed ex-criminal Mehmed Krasnichi. But can Jude keep his search party from falling apart?

When Donis Xenakis, a Greek riot-policeman and ‘Neo-Hellenic Front’ sympathiser, gets caught up in a diabolical plot to attack migrants, Jude could never have anticipated the unimaginable danger Alban is in. Nor can he foresee how a trafficked girl there will change all their outcomes.

‘The Migrant’ is a tense and evocative ‘road adventure’ with a powerful message and a tragic, yet ultimately redemptive, twist.’

Publisher: ‘Instant Apostle’.

Previously by this author:

Published on August 04, 2018 13:59

•

Tags:

2012, albania, anti-austerity-riots, athens, economic-crisis, greece, migration

Road trip with 'The Migrant'

A case of mistaken identity

As I cycled along a city ring road once, my saddle was grasped from behind. A youth on a bike with cow horn handlebars scraped his shoe along the tarmac as he dragged us both to a standstill. He simply stared at me.

“What do… you want?” I said. He didn’t offer a word. His fist then slammed into my nose. He yanked back on his cow horns and wheelied off.

In the wake of the Black Lives Matter protests following the death of George Floyd, many previously silent people have given voice to their own experiences of racism. Like other mixed-race children growing up in England, I too felt a measure of it.

Another time, when I found a school door was locked, I tapped on the glass at a passer-by to let me in. He opened the door, showered me with a face full of spittle, locked it again and walked off. Sometimes, motives for actions were not stated; on other occasions, however, they were verbalised with venom.

I was aware then, though, that many English children were mistreated, often worse than me, for being different in some other way. Though my own experiences hurt, they were far outweighed by the friendship, help and affirmation I received from others in England as I grew up. Everyone needs to learn to forgive those who sin against them, as our own thoughts, words and deeds against others are forgiven.

When as an adult I moved to live and work with the church in Albania, I experienced racism from another angle: how some Greeks view those from their neighbouring country. When one Greek filling-station attendant eyed my Albanian car registration plate, I was actually refused petrol. I am stopped and questioned constantly by the Greek police on motorways, at road-toll stations and in supermarket car parks. Then, a cheerful ‘good morning’ and an offering of my British passport noticeably changes their attitude and my treatment.

This brings its own particular feeling of mistreatment: of being mistaken for something you know you are not. It perhaps gets to the crux of the matter: being seen as inferior, less human, potentially criminal even, on the basis of a wrong assumption. It has certainly made me more sympathetic to Albanians.

Many of these incidents of ‘mistaken racism’ were reworked into a novel I wrote called ‘The Migrant’. It tells the story of an Albanian youth who sets off to Greece in search of work and a better life, and three friends who set off to Athens to find him. There they encounter police brutality and casual racism on the roads, as well as populist rallies and organised attacks by a resurgent far right group.

On their way home, as the characters lament such struggles, they talk of a time and place where people of every race and nation will be welcomed and equally valued: where there will be no more crying and pain. Until then, there is longsuffering for so many, but it is eased with a sweet and certain hope that this place is prepared for us - and that we will get there.

'Racism... that's illogical captain!'

Paul Alkazraji's novel ‘The Migrant’ is published by Instant Apostle.

Find copies of ‘The Migrant’ here: https://www.amazon.co.uk/gp/product/B...

'The Migrant' Novel - Q and A

The author Paul Alkazraji in the Albanian mountains

close to the border with Greece. Pic: Andrew LaSavio.

Where does the story begin?

In the spectacular forested mountains bordering Albania and Greece, close to Little Prespa Lake, at dusk. A young Albanian man, Alban, and his friend, sneak past a watchtower to enter Greece illegally in search of work, but they are spotted by a border guard and a chase to catch them begins.

What is the story about?

It is about a pastor, Jude Kilburn, who takes on the responsibility to care enough for another person in his village, the young man, Alban, that he is ready to go the extra kilometre, over 500 of them in fact, to Athens to see if he is safe.

What happens in Athens?

Jude arrives in the Greek capital as dangers all around Alban are building - violent anti-austerity riots, the rise of far right political groups and racist attacks, the clutches of a trafficking gang, and a cynical police operation - then races against time to find him.

Did you personally make the journey in the story from Albania to Athens?

Yes, I drove down through Greece myself in an old Mercedes with two companions to experience the sights and sounds of the country, past Mount Olympus and Delphi. I then spent time in central Athens, in Plaka and Exarcheia, so I could evoke a keen sense of time and place as a backdrop.

The view across Athens from the Acropolis.

What inspired you to write it?

I have worked for some years in Albania, and seen first-hand the struggles and risks many Albanians face to escape poverty and unemployment and find work abroad. It is, in a way, their story I am telling.

What are its themes?

It deals with people searching for a better life, without poverty or violent conflict, with migrants of the recent mass-movements up through southern Europe, and with dreams that turn sour. It deals too with where our final hope lies for finding such a destination of prosperity and peace.

Do you have a favourite scene from the book?

There are scenes on the Acropolis and in the middle of a riot in Syntagma Square and more that I hope are vivid enough to immerse the reader totally in energy of the moment.

Do you have a favourite minor character?

Some of them would be ‘Che’ Chaconas the anarchist, Granit Korabi the criminal gang member, and Stavros ‘The Big Man’ and Neo-Hellenic Front member. But the protagonist, Jude, the pastor who takes on the search for Alban, has more of my personal empathy.

Do you have a favourite sentence from the book?

The life of the poet Lord Byron has parallels with Alban’s life, and I have quoted him a few times. This one from ‘Don Juan’ is a favourite: ‘Between two worlds life hovers like a star, twixt night and morn, upon the horizon's verge.’ It sums up the story.

Can we guess the ending?

There is a kind of justice in what happens in the epilogue. Originally, it wasn’t planned that way, so I didn’t! The scene was added later. But maybe you will guess it?

Amazon links to 'The Migrant':

UK: https://www.amazon.co.uk/Migrant-Paul...

US: https://www.amazon.com/gp/product/B07...

'The Migrant' blog tour 2021

'The Migrant': Three incompatible characters set off from Albania on a dangerous journey to find a missing relative in Athens at the time of Greece’s economic crisis, encountering police brutality, racism and restored relationships along the way.

Follow the blog tour here as seven writers share their thoughts about the novel...

Blog Tour #1 'And what... makes this novel so good, well to start with its the main character, Pastor Jude Kilburn as he is taken through a perilous journey...' says Lynsey Adams. (Scroll down a little.)

https://readingbetweenthelines4067781...

Blog Tour #2 A very thoughtful and engaged review from S C Skillman. @scskillman

https://scskillman.com/2021/09/07/boo...

Migrants make for the mountains

Albanians heading for the mountains. Pics, Peter Wilson.

Excerpt from 'The Migrant' novel: A suspense story about a British Pastor, Jude Kilburn, as he travels to Athens to find an Albanian member of his church, Alban Gurbardhi, who has migrated there illegally in search of a better life. This as the riots surrounding Greece’s recent economic collapse explode, and a neo-Nazi movement closes in for a fatal, racist attack on Alban.

From Chapter 1.

Context: Alban Gurbardhi and his friend Ervin run into trouble as they attempt to cross the border illegally between Albania and northern Greece in search of work.

Ten minutes later, he was following the ravine back upstream until he could make out the arch of the stone bridge ahead of him. The sound of Ervin screaming and pleading had grown louder. He winced. He crawled closer on his front up a bank and set aside his sack. He peered over the edge of the clearing and he saw his friend being held by his shirt at the neck. The policeman flung him down and kicked him. Ervin moaned and rolled over.

Sliding back down lower, Alban closed his eyes. He thought about what he could do. He opened them and looked at his hands. They were trembling. He saw a broken branch by his side. It looked thick but dry and rotten. He stretched his hand towards it, and with the tips of his fingers pulled it closer and into his palm. He eased himself onto his back and began to breathe deeply. He saw his breath steam rise high in gusts. He looked up at the millions of stars in the clear Balkan night above him. In his field of vision the policeman suddenly entered and stood looking down on him. For a split second he saw his broad, muscular shoulders, his hair sheared close across his temples, and his eyes – yet one was odd. In fear and panic he brought the branch up into the man’s face and it smashed there into pieces. The man groped at his eyes and tumbled down the bank.

Alban got to his feet, grabbed his sack and ran towards Ervin. He pulled him up off the ground and looked at his face. It was dark and blood-sticky.

‘Hey, friend. Are you coming with me to Greece?’ he shouted. A grin broke across Ervin’s dazed face. Alban clutched his shirt and dragged him forwards, stumbling over the clearing. They tore down the edge of the treeline together. Soon they were running parallel to the ravine. Alban’s sack caught a branch and was snagged from his hand. He stopped to retrieve it. He looked back. The policeman was up now and coming.

They came to a rocky hillock and bounded up it like young goats and then down the other side into a hedge of rosehip bushes. Ervin waded through them ahead lifting the long fronds aside so that they would not snap back on him. Alban, though, felt the thorns of one cut into the flesh of his shoulder and he cried out. They tumbled out of the other side onto the grass and crawled forward until they came to the edge of the land. Alban looked down. Below them was an almost sheer bank of earth falling to the rocky bed of the stream perhaps fifty metres down. He looked out over the mountains before them. The moonlight caught a row of wind turbines on a distant ridgeline. He could smell Ervin’s sweat and blood. He thought he heard the bear growl far away, but he was sure he heard a man grunt and spit. He turned to look behind them. On the top of the hillock the policeman stood against the stars. He reached his hand down to the holster on his thigh and drew out the fat, black pistol.

‘You little dogs!’ he shouted. He mounted it across his right forearm with his left hand. Alban grabbed his friend’s arm and dragged him over the edge as two shots cracked out and echoed along the ravine.

Copyright Paul Alkazraji, Instant Apostle.

The first two chapters can be read here:

https://read.amazon.com/kp/embed?prev...

A good day's wage in Albania (1200 leke/£8.40) making work over the border in Greece a prospect many see as worth taking risks for.

For more about 'The Migrant' click on the cover:

The Albania to Athens quiz

Check your general knowledge of Albania and Greece. Try this free, easy quiz on Goodreads drawn from my novel ‘The Migrant’.

What is the road border crossing from Albania to Greece (near Bilisht) called by people on the Albanian side?

Who was the Prime Minister of Greece in September 2012 when events in the story are set?

The quiz is here: https://www.goodreads.com/quizzes/113...

From Albania to the English Channel

Albanians heading for the mountains. Pics, Peter Wilson.

Just why are so many young Albanian men crossing the English Channel on small boats? Their story is paralleled in Alban’s, caught in rural poverty, and heading first for Greece in ‘The Migrant’ novel.

https://www.goodreads.com/review/show...

From Chapter 1.

Context: Alban Gurbardhi and his friend Ervin run into trouble as they attempt to cross the border illegally between Albania and northern Greece in search of work.

Ten minutes later, he was following the ravine back upstream until he could make out the arch of the stone bridge ahead of him. The sound of Ervin screaming and pleading had grown louder. He winced. He crawled closer on his front up a bank and set aside his sack. He peered over the edge of the clearing and he saw his friend being held by his shirt at the neck. The policeman flung him down and kicked him. Ervin moaned and rolled over.

Sliding back down lower, Alban closed his eyes. He thought about what he could do. He opened them and looked at his hands. They were trembling. He saw a broken branch by his side. It looked thick but dry and rotten. He stretched his hand towards it, and with the tips of his fingers pulled it closer and into his palm. He eased himself onto his back and began to breathe deeply. He saw his breath steam rise high in gusts. He looked up at the millions of stars in the clear Balkan night above him. In his field of vision the policeman suddenly entered and stood looking down on him. For a split second he saw his broad, muscular shoulders, his hair sheared close across his temples, and his eyes – yet one was odd. In fear and panic he brought the branch up into the man’s face and it smashed there into pieces. The man groped at his eyes and tumbled down the bank.

Alban got to his feet, grabbed his sack and ran towards Ervin. He pulled him up off the ground and looked at his face. It was dark and blood-sticky.

‘Hey, friend. Are you coming with me to Greece?’ he shouted. A grin broke across Ervin’s dazed face. Alban clutched his shirt and dragged him forwards, stumbling over the clearing. They tore down the edge of the treeline together. Soon they were running parallel to the ravine. Alban’s sack caught a branch and was snagged from his hand. He stopped to retrieve it. He looked back. The policeman was up now and coming.

They came to a rocky hillock and bounded up it like young goats and then down the other side into a hedge of rosehip bushes. Ervin waded through them ahead lifting the long fronds aside so that they would not snap back on him. Alban, though, felt the thorns of one cut into the flesh of his shoulder and he cried out. They tumbled out of the other side onto the grass and crawled forward until they came to the edge of the land. Alban looked down. Below them was an almost sheer bank of earth falling to the rocky bed of the stream perhaps fifty metres down. He looked out over the mountains before them. The moonlight caught a row of wind turbines on a distant ridgeline. He could smell Ervin’s sweat and blood. He thought he heard the bear growl far away, but he was sure he heard a man grunt and spit. He turned to look behind them. On the top of the hillock the policeman stood against the stars. He reached his hand down to the holster on his thigh and drew out the fat, black pistol.

‘You little dogs!’ he shouted. He mounted it across his right forearm with his left hand. Alban grabbed his friend’s arm and dragged him over the edge as two shots cracked out and echoed along the ravine.

Copyright Paul Alkazraji, Instant Apostle.

The first two chapters can be read here:

https://read.amazon.com/kp/embed?prev...

A good day's wage in Albania (1200 leke/£8.90) making work over the border in Greece and in Northern Europe a prospect many see as worth taking risks for.

For more about 'The Migrant' click on the cover:

With Ruth O Reilly Smith in the UCB2 studio

An in depth chat with Ruth O Reilly Smith in the UCB2 studio covered cross-channel migration by Albanians, ‘The Migrant’ novel, why the future once seemed like choosing a cereal brand from a supermarket shelf, and why Robin Mark’s ‘Days of Elijah’ speaks to me. Click on the link for 27/03/2023

https://www.ucb.co.uk/ruth

By this author.