Paul Alkazraji's Blog - Posts Tagged "church"

Pope Francis honours Albania’s persecuted and thanks ’alive’ church (+ radio interview)

Communist monument in southern Albania.

By Paul Alkazraji in Albania (Sunday, September 21st, 2014).

Along the Boulevard of National Martyrs in Albania’s capital Tirana photos of the priests and nuns who fell victim to the country’s violent Communist persecutions were draped in remembrance before Pope Francis and the tens of thousands gathered on Sunday for the Mass and his homily.

In addition to the key themes of encouraging Albania’s young to build their lives in Christ, and fostering peaceful co-existence between the different religious communities, he drew attention to how the country had “suffered so much because of a terrible atheist regime”.

“Albania sadly witnessed the violence and tragedy that can be caused by a forced exclusion of God from personal and communal life,” he said. “When, in the name of an ideology, there is an attempt to remove God from a society, it ends up adoring idols, and very soon people lose their way, their dignity trampled and rights violated.”

After their rise to power near the end of WWII, the Communists decreed that the activities of all religious communities be supervised by the state. It was after Mao Zedong’s Cultural Revolution in 1966 spawned a similar movement in Albania, however, that the church faced its darkest hour.

Student agitators roamed the countryside forcing people to renounce their faith. The remnants of the fledgling Protestant church was driven further underground. Catholic and Orthodox priests were interned and over a hundred and twenty died through the harsh conditions, torture or execution. Outside a cemetery in the northern city of Shkoder many were shot by firing squad. Around 2000 churches and mosques were destroyed or converted into warehouses or gymnasiums. To achieve ‘the world’s first atheist state’ faith communities were obliterated.

Of those that survived to tell their stories the Franciscan Zef Pllumi emerged as an articulate voice through his book, ‘Live to Tell’, an account of his cruel treatment in internment camps. Often called the Albanian ‘Gulag Archipelago’ due to its similarities to Alexander Solzhenitsyn’s work, some find it difficult to even endure reading its narrative of suffering.

On that morning of Pope Francis’ visit, as I drove with the leaders of a new village church-plant close to the site of one of the places Zef Pllumi was imprisoned, at the Orman-Pojanit camp near Maliq, one told me a further story. It was of a priest who had been beaten about the head and buried alive there.

A second-century Church Father wrote those well-known words ‘the blood of martyrs is the seed of the Church’. Close to the periphery of that camp site, there are now two flourishing churches filled with happy, worshipping communities every Sunday, with a third also growing. At one, in a village, twenty new believers were baptised this summer. May it delight that priest in heaven to know it.

One of the new believers, a man in his seventies who lived through those times, waded out into the lake for his baptism with abandon in his long-johns, and speaks of how he could not imagine that his life would change so much at this stage. “I sleep much better. My heart is filled with the love of God, and praying all the time gives me new strength,” he says.

From Mother Teresa Square down the Boulevard of National Martyrs Pope Francis spoke the final words of his homily. “To the Church which is alive in this land of Albania, I say “thank you” for the example of fidelity to the Gospel! So many of your sons and daughters have suffered for Christ, even to the point of sacrificing their lives. May their witness sustain your steps today and tomorrow as you journey along the way of love, of freedom, of justice and of peace.”

End.

Radio interview on United Christian Broadcasters for the Paul Hammond Show about Albania and the Pope's visit (23/9/14): http://www.mixcloud.com/Muthena/pope-...

By this writer: The Silencer

The remnants of the Albanian protestant church discovered in 1991

(From Chapter 4 ‘Midnight by the railway tracks’, Christ and the Kalashnikov.)

Later that afternoon, as we hovered around the hotel lobby anxiously biding our time, I sensed that there were many others in the building watching us. At quarter to four, I glanced around at the team. It was time to step out, and my stomach seemed to rise like when speeding in a car across a humpbacked bridge. Together we walked through the glass entrance doors and around to the park at the rear. The security officer scurried quickly after us. As we crossed the grass my heart sank; there were little more than around thirty people ahead, casting their eyes around uneasily, and I couldn’t see Sokoli. I wondered if what we were going to try was led by the Holy Spirit or just foolhardy. We quickly set up a sketchboard to paint a visual message, and the YWAM team began to perform a short drama. It was then that I noticed something. All around the edge of the park, people were watching at a distance. As the presentation continued they began to edge timidly forwards, glancing at each other and us. As the drama drew to a close, we were surrounded by literally hundreds.

The moment in the programme had arrived to preach a short message, and yet no one spoke Albanian fluently enough to do it. I glanced around anxiously, grasping my Bible, and then began in English. Suddenly, a young man with curly, brown hair stepped forwards from the crowd. “My name is Ardian,” he said quickly, “I will translate for you.” As I continued to speak, Ardian relayed the message confidently to the crowd. My pulse was racing. I was amazed and I thanked God under my breath. I now watched the faces of those close in front of us as they stood jostling and craning their necks for a better view. As I spoke, I had never witnessed a crowd polarise so visibly to what they were hearing: an ageing woman in a black headscarf whose eyes narrowed as she pulled away; a teenage boy with a half-grown moustache whose mouth began to widen like a fish. It was as if a light was shining so clearly in the park that there were no grey areas, just highlight and shadow across the people’s faces. When Ardian finished translating, he concluded as if his heart had made its own choice as he’d stood there: “I know this message is true, because it was so for me,” he declared. I stepped back up onto the edge of a small, stone platform. By now the crowd had spread back across the grass. People were climbing up trees and standing on the tops of park benches, and around the edges of the grass were dozens of soldiers who had been listening in to the talk. Suddenly, shouting broke out at the rear of the crowd and people began to scatter across the grass. Four police cars had braked in the road, and the officers appeared to be arguing amongst themselves as well as trying to break through the people. The soldiers, however, were crowding up to them red-faced and pushing them back, waving their arms in the air. I looked back down at the team. It seemed like the right moment to leave. We packed up the equipment we had brought, and mingled in with the crowds as the park began to empty rapidly.

Back at the hotel, we were floating but afraid. No one could quite believe the response that we’d had, and how Ardian, whom I now remembered meeting briefly in Thessaloniki, had stepped forward publicly at great risk to himself. One black mark in your biography file could mean interrogations or worse, and the Sigurimi were always watching. Our brown-suited spy had seen it all, and we knew he’d make his reports. We held our breath and waited for the ensuing consequences throughout the evening.

A soft tapping came on the door of my hotel room at around midnight. My roommate looked anxiously across. I pulled on my shoes, and moments later turned the key in the lock. I opened the door cautiously. Outside in the corridor stood an old man with dark, bushy eyebrows and a warm expression. He held out his hand. “I am Ligor Çina, a member of the church in Korçë,” he whispered. He beckoned for us to follow him. I felt a little apprehensive, but at peace somehow that the man’s introduction was genuine. We locked the room and followed a couple of paces behind him down the silent hotel corridor.

Just five minutes walk from the entrance of the Hotel Iliria, we entered a small stone cottage, ducking to avoid the lintel. The interior was dimly lit and smelt a little of feet. Ligor gestured us through a further doorway where another elderly man with dark, sparking eyes sat regally on a wooden chair, his face half-lit by a single light bulb. A candle was flickering on the window ledge. Ligor introduced the man as ‘Koci Treska’. I stepped forwards and shook his hand. After we had sat across from him, he wasted no time in addressing us, and I waited for my roommate to translate. As I watched him talk, his manner seemed formal, yet I could see tears in his eyes. He brushed his cheek intermittently with his hand. Despite his frail physique, the man possessed a noticeable inner strength. I could feel my own tears welling up before I knew what he was saying. Shortly, my roommate turned to look at me.

“He says that he, Ligor and a handful of others are the only remaining members of a church stared before the outbreak of the Second World War… by two American missionaries, Kennedy and Jaques… They were the youth group,” he said, pausing whilst he too now steadied his voice. “He says that they have kept their faith secretly for over fifty years, and word reached him today that the Gospel had been preached on the streets of his town for the first time since the Communists took control. He wanted to meet us and to thank us. He has been praying for this day for years. He says that he is ready now to die with contentment.” I too now brushed my cheek. He reached forwards and for a couple of seconds we clasped hands. My roommate continued: “He says that we should go now, but he hopes that we will return here.” I was overcome – a lifetime of covert belief, and we were his first confidants. Koci now gestured towards the door. The meeting was over. As we stood up to leave, Ligor stepped ahead of us. Outside the cottage, he looked both ways. We shook hands firmly, and we scurried away along the dark, side street.

Copyright Paul Alkazraji. Christ and the Kalashnikov, Marshall Pickering. 2001. All Rights Reserved.

By this writer: Christ and the Kalashnikov

Published on September 25, 2014 03:36

•

Tags:

albania, alexander-solzhenitsyn, catholic, church, communism, cultural-revolution, mao-zedong, mother-teresa-square, orthodox, pope-francis, protestant, sigurimi, thessaloniki, ywam, zef-pllumi

Road trip with 'The Migrant'

A case of mistaken identity

As I cycled along a city ring road once, my saddle was grasped from behind. A youth on a bike with cow horn handlebars scraped his shoe along the tarmac as he dragged us both to a standstill. He simply stared at me.

“What do… you want?” I said. He didn’t offer a word. His fist then slammed into my nose. He yanked back on his cow horns and wheelied off.

In the wake of the Black Lives Matter protests following the death of George Floyd, many previously silent people have given voice to their own experiences of racism. Like other mixed-race children growing up in England, I too felt a measure of it.

Another time, when I found a school door was locked, I tapped on the glass at a passer-by to let me in. He opened the door, showered me with a face full of spittle, locked it again and walked off. Sometimes, motives for actions were not stated; on other occasions, however, they were verbalised with venom.

I was aware then, though, that many English children were mistreated, often worse than me, for being different in some other way. Though my own experiences hurt, they were far outweighed by the friendship, help and affirmation I received from others in England as I grew up. Everyone needs to learn to forgive those who sin against them, as our own thoughts, words and deeds against others are forgiven.

When as an adult I moved to live and work with the church in Albania, I experienced racism from another angle: how some Greeks view those from their neighbouring country. When one Greek filling-station attendant eyed my Albanian car registration plate, I was actually refused petrol. I am stopped and questioned constantly by the Greek police on motorways, at road-toll stations and in supermarket car parks. Then, a cheerful ‘good morning’ and an offering of my British passport noticeably changes their attitude and my treatment.

This brings its own particular feeling of mistreatment: of being mistaken for something you know you are not. It perhaps gets to the crux of the matter: being seen as inferior, less human, potentially criminal even, on the basis of a wrong assumption. It has certainly made me more sympathetic to Albanians.

Many of these incidents of ‘mistaken racism’ were reworked into a novel I wrote called ‘The Migrant’. It tells the story of an Albanian youth who sets off to Greece in search of work and a better life, and three friends who set off to Athens to find him. There they encounter police brutality and casual racism on the roads, as well as populist rallies and organised attacks by a resurgent far right group.

On their way home, as the characters lament such struggles, they talk of a time and place where people of every race and nation will be welcomed and equally valued: where there will be no more crying and pain. Until then, there is longsuffering for so many, but it is eased with a sweet and certain hope that this place is prepared for us - and that we will get there.

'Racism... that's illogical captain!'

Paul Alkazraji's novel ‘The Migrant’ is published by Instant Apostle.

Find copies of ‘The Migrant’ here: https://www.amazon.co.uk/gp/product/B...

'The Migrant' Novel - Q and A

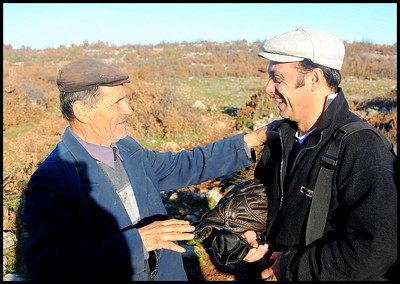

The author Paul Alkazraji in the Albanian mountains

close to the border with Greece. Pic: Andrew LaSavio.

Where does the story begin?

In the spectacular forested mountains bordering Albania and Greece, close to Little Prespa Lake, at dusk. A young Albanian man, Alban, and his friend, sneak past a watchtower to enter Greece illegally in search of work, but they are spotted by a border guard and a chase to catch them begins.

What is the story about?

It is about a pastor, Jude Kilburn, who takes on the responsibility to care enough for another person in his village, the young man, Alban, that he is ready to go the extra kilometre, over 500 of them in fact, to Athens to see if he is safe.

What happens in Athens?

Jude arrives in the Greek capital as dangers all around Alban are building - violent anti-austerity riots, the rise of far right political groups and racist attacks, the clutches of a trafficking gang, and a cynical police operation - then races against time to find him.

Did you personally make the journey in the story from Albania to Athens?

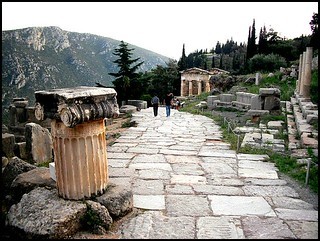

Yes, I drove down through Greece myself in an old Mercedes with two companions to experience the sights and sounds of the country, past Mount Olympus and Delphi. I then spent time in central Athens, in Plaka and Exarcheia, so I could evoke a keen sense of time and place as a backdrop.

The view across Athens from the Acropolis.

What inspired you to write it?

I have worked for some years in Albania, and seen first-hand the struggles and risks many Albanians face to escape poverty and unemployment and find work abroad. It is, in a way, their story I am telling.

What are its themes?

It deals with people searching for a better life, without poverty or violent conflict, with migrants of the recent mass-movements up through southern Europe, and with dreams that turn sour. It deals too with where our final hope lies for finding such a destination of prosperity and peace.

Do you have a favourite scene from the book?

There are scenes on the Acropolis and in the middle of a riot in Syntagma Square and more that I hope are vivid enough to immerse the reader totally in energy of the moment.

Do you have a favourite minor character?

Some of them would be ‘Che’ Chaconas the anarchist, Granit Korabi the criminal gang member, and Stavros ‘The Big Man’ and Neo-Hellenic Front member. But the protagonist, Jude, the pastor who takes on the search for Alban, has more of my personal empathy.

Do you have a favourite sentence from the book?

The life of the poet Lord Byron has parallels with Alban’s life, and I have quoted him a few times. This one from ‘Don Juan’ is a favourite: ‘Between two worlds life hovers like a star, twixt night and morn, upon the horizon's verge.’ It sums up the story.

Can we guess the ending?

There is a kind of justice in what happens in the epilogue. Originally, it wasn’t planned that way, so I didn’t! The scene was added later. But maybe you will guess it?

Amazon links to 'The Migrant':

UK: https://www.amazon.co.uk/Migrant-Paul...

US: https://www.amazon.com/gp/product/B07...

'Heart of a Hooligan': Dave Jeal's story

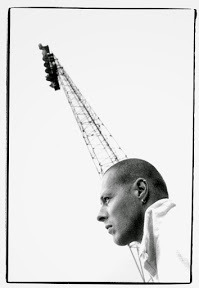

Paul Alkazraji and Dave Jeal. Bristol, UK, Summer 2013.

Here is one of the original newspaper reports that led to the writing of the book.

From Hooligan to Holiness.

For Dave Jeal football violence had become a way of life. He talks to PAUL ALKAZRAJI about how becoming a Christian has given him a whole new set of goals.

Dave Jeal's appearance is a touch deceptive. He sports exactly the kind of haircut you would expect of someone who was, until recently, involved in the disturbing world of football violence. It comes as a revealing surprise, then, to find he had his head shorn only recently whilst working with Ark Christian Ministries amongst homeless people in South Africa.

Throughout the mid-Eighties and early Nineties Dave Jeal wore a neatly cut bob and was a 'casual', a 'boy', a member of a Bristol Rovers 'firm' know as the Young Executives. In layperson's English he was at the centre of gang fighting both at league matches and as an England Supporter during the 1990 World Cup.

"I first started going to football in 1972 when I was seven years old," he told me. "I left school at 15 and got in with a dodgy group of lads, and it just got out of hand really. It started off with us coining the away fans and things like that, then it got a bit more involved. We would get to the matches early to see where they parked their cars, and then leave early to go and wait for them. It was mindless violence."

"If Rovers were playing a Welsh club, we'd get to their town centres early, take as many liberties as we could, and try and find out where their firms' pubs were. The object was to take ground. There would be a lot of shouting, one or two punches might be thrown, and then one lot would run. It was a scary game. I've had bleach sprayed in my eyes and I lost my eye socket I've got a plastic one now. I've also got a false tooth and a broken nose. I wasn't very good at it."

Dave also travelled with rival Bristol City fans to England away matches. "During the 1990 World Cup Semi-Final we went in the German end of the stadium with the intention of unfurling our Union Jacks over the German flags, but we got marched out at gunpoint by the Italian police. On the way back to Naples they made us get off at a station where all the German fans were: 400 of them and about 30 of us. We ran into the Germans and this guy fired a flare pistol straight at me. It was bizarre. It can only have been God: it just went up and over my head."

Dave explained to me that the reality of evil impressed itself powerfully upon him during an incident in Stockholm, and it proved to be a turning point in his life. "In 1992 I went to Sweden for the European Championships. England got knocked out by Sweden and there was a full-scale riot outside the ground. I climbed a fence with another guy and got involved in a scuffle with some Swedish fans, and I started kicking one. I ran off up the road, and when I came back about 15 minutes later there were still six or seven lads kicking him on the ground. He was unconscious and he wasn't moving. It just sickened me.”

"I walked back to the stadium where we were sleeping, and I sensed this deeply evil presence all over Stockholm. It think it was because of the wickedness I had seen and had a hand in. My mum was a member of the Salvation Army and I phoned her up and asked her to pray for me. I was petrified."

Early the next day Dave began making his way towards the airport. "I was walking through a subway and there was no one else around," he told me. "Out of nowhere this Salvation Army guy came up the other way and stopped and looked at me. He smiled and nodded. He didn't say anything. It was bizarre. When I got back home I decided I would make a new start but I didn't."

Two and a half years ago, whilst volunteering at a project for Bristol's homeless run by his mother, Dave told me that he "took a shine" to a fellow helper, who invited him to her church. "I went to a service and I hated it. About 10 minutes before the end I just burst into tears. It freaked me, so I ran out to the pub and got pretty hammered. She invited me back, so I went to prove to myself it wouldn't happen again. It did, only this time I was locked in the middle of a row and 1 couldn't get out.”

"These two guys asked me if they could pray for me. I said, 'You can do what you want!' They said, 'Well, what do you want?' Then it hit me. I said 'I want all the anger and hate and pain inside me to go.' They said, 'Do you accept Jesus Christ' I said, 'All right,' and the next thing I knew I was laid out in the middle of all these chairs. I got up and I felt like this massive rucksack I had been carrying around my whole life had just been lifted off me."

Dave subsequently joined the congregation of Wood lands Road Church in Bristol. "It hasn't been easy for them or for me, because I like to call a spade a spade," he says. "I had this thing that I'm working class and I wouldn't be accepted, because most churches are middle class, but my church has been brilliant. They have given me so much support."

For the last two years Dave has helped run their youth group, and is in the process of starting up a half-way house for ex-prisoners and drug users emerging from rehabilitation, with the backing of his church. He has a warmth and gentleness which belies his history and are a testament to God's work.

I asked him how his mum had reacted to the news. "She had just got back from her holiday. I had been trying to phone her all afternoon, and I said, 'Mum I've got something to tell you.' It went really quiet. I said, 'I've become a Christian,' and she just screamed and she was crying."

Dave still attends Bristol Rovers matches, though no longer for the dark exhilaration of 'firm' membership. He still maintains old friendships, however, so I asked him how his new allegiance went down on the terraces. "They think it's hilarious," he told me with a grin.

"I went on Sunday with my girlfriend and some people from church. They were saying, 'Is this part of your new firm then?' I said 'Yes its God's firm!”

"The referee made a dodgy decision, and I was dying to shout abuse at him. They noticed and said, 'You wanted to swear then, didn't you' I said, 'Yes? They think that's brilliant, and that I'm still one of the lads. I am and I'm not, if you know what I mean."

Originally printed in the 12th June 1998 issue of the UK’s Catholic Herald.

Dave Jeal, 1998.

By Paul Alkazraji.

Published on February 25, 2021 08:46

•

Tags:

bristol-rovers, christianity, church, dave-jeal, england, european-championships, football, hooliganism, jesus, juventus-fc, millwall-fc, paul-gascoigne, soccer, stockholm, turin, united-kingdom, violence, world-cup

'The Migrant' blog tour 2021

'The Migrant': Three incompatible characters set off from Albania on a dangerous journey to find a missing relative in Athens at the time of Greece’s economic crisis, encountering police brutality, racism and restored relationships along the way.

Follow the blog tour here as seven writers share their thoughts about the novel...

Blog Tour #1 'And what... makes this novel so good, well to start with its the main character, Pastor Jude Kilburn as he is taken through a perilous journey...' says Lynsey Adams. (Scroll down a little.)

https://readingbetweenthelines4067781...

Blog Tour #2 A very thoughtful and engaged review from S C Skillman. @scskillman

https://scskillman.com/2021/09/07/boo...

The Albania to Athens quiz

Check your general knowledge of Albania and Greece. Try this free, easy quiz on Goodreads drawn from my novel ‘The Migrant’.

What is the road border crossing from Albania to Greece (near Bilisht) called by people on the Albanian side?

Who was the Prime Minister of Greece in September 2012 when events in the story are set?

The quiz is here: https://www.goodreads.com/quizzes/113...

From Albania to the English Channel

Albanians heading for the mountains. Pics, Peter Wilson.

Just why are so many young Albanian men crossing the English Channel on small boats? Their story is paralleled in Alban’s, caught in rural poverty, and heading first for Greece in ‘The Migrant’ novel.

https://www.goodreads.com/review/show...

From Chapter 1.

Context: Alban Gurbardhi and his friend Ervin run into trouble as they attempt to cross the border illegally between Albania and northern Greece in search of work.

Ten minutes later, he was following the ravine back upstream until he could make out the arch of the stone bridge ahead of him. The sound of Ervin screaming and pleading had grown louder. He winced. He crawled closer on his front up a bank and set aside his sack. He peered over the edge of the clearing and he saw his friend being held by his shirt at the neck. The policeman flung him down and kicked him. Ervin moaned and rolled over.

Sliding back down lower, Alban closed his eyes. He thought about what he could do. He opened them and looked at his hands. They were trembling. He saw a broken branch by his side. It looked thick but dry and rotten. He stretched his hand towards it, and with the tips of his fingers pulled it closer and into his palm. He eased himself onto his back and began to breathe deeply. He saw his breath steam rise high in gusts. He looked up at the millions of stars in the clear Balkan night above him. In his field of vision the policeman suddenly entered and stood looking down on him. For a split second he saw his broad, muscular shoulders, his hair sheared close across his temples, and his eyes – yet one was odd. In fear and panic he brought the branch up into the man’s face and it smashed there into pieces. The man groped at his eyes and tumbled down the bank.

Alban got to his feet, grabbed his sack and ran towards Ervin. He pulled him up off the ground and looked at his face. It was dark and blood-sticky.

‘Hey, friend. Are you coming with me to Greece?’ he shouted. A grin broke across Ervin’s dazed face. Alban clutched his shirt and dragged him forwards, stumbling over the clearing. They tore down the edge of the treeline together. Soon they were running parallel to the ravine. Alban’s sack caught a branch and was snagged from his hand. He stopped to retrieve it. He looked back. The policeman was up now and coming.

They came to a rocky hillock and bounded up it like young goats and then down the other side into a hedge of rosehip bushes. Ervin waded through them ahead lifting the long fronds aside so that they would not snap back on him. Alban, though, felt the thorns of one cut into the flesh of his shoulder and he cried out. They tumbled out of the other side onto the grass and crawled forward until they came to the edge of the land. Alban looked down. Below them was an almost sheer bank of earth falling to the rocky bed of the stream perhaps fifty metres down. He looked out over the mountains before them. The moonlight caught a row of wind turbines on a distant ridgeline. He could smell Ervin’s sweat and blood. He thought he heard the bear growl far away, but he was sure he heard a man grunt and spit. He turned to look behind them. On the top of the hillock the policeman stood against the stars. He reached his hand down to the holster on his thigh and drew out the fat, black pistol.

‘You little dogs!’ he shouted. He mounted it across his right forearm with his left hand. Alban grabbed his friend’s arm and dragged him over the edge as two shots cracked out and echoed along the ravine.

Copyright Paul Alkazraji, Instant Apostle.

The first two chapters can be read here:

https://read.amazon.com/kp/embed?prev...

A good day's wage in Albania (1200 leke/£8.90) making work over the border in Greece and in Northern Europe a prospect many see as worth taking risks for.

For more about 'The Migrant' click on the cover:

With Ruth O Reilly Smith in the UCB2 studio

An in depth chat with Ruth O Reilly Smith in the UCB2 studio covered cross-channel migration by Albanians, ‘The Migrant’ novel, why the future once seemed like choosing a cereal brand from a supermarket shelf, and why Robin Mark’s ‘Days of Elijah’ speaks to me. Click on the link for 27/03/2023

https://www.ucb.co.uk/ruth

By this author.

Tasters from ‘The Migrant’ novel.

A pastor sets off on a dangerous journey to find a missing Albanian member of his church in Athens at the time of Greece’s economic crisis, encountering police brutality, racism and restored relationships along the way.

In an Albanian village. (Chapter 2.)

As the route became tarmac, an old man in a blue cloth

cap sat on an upturned milk crate at the gate of his yard.

He scrutinised Jude and raised his hand in a clenched fist

salute to greet and halt him.

‘Death to fascism!’ he shouted.

‘Freedom for the people,’ Jude called back to humour

him. He knew old Fatos had at one time been the village

headman, and still kept up his self-appointed monitoring

duties.

‘Where is your permit to be here?’ said Fatos.

‘Where is your permit to ask people if they have a

permit?’ asked Jude. The man slapped his knee and

laughed. ‘How are you, Fatos? And everyone in your

house?’

‘Mirë, mirë,’ he said. Jude walked over and smiled at him

as he shook his hand, and kept on moving. He then spun

around and saluted him again with his fist. The man

grinned broadly.

On the roads south through Greece. (Chapters 7 and 9).

Soon they were through Kozani and driving out in open

country, and Jude watched the scenery slide by. There

were solar panels the size of billboards in fields flashing in

the midday sun. A lorry was parked with the entire cabin

tilted forwards as if it had expired in the heat. As they

climbed into the hills, they passed clusters of Orthodox

shrines along the roadside like rusty mailboxes. One was a

perfect miniature church with red roof tiles and a bell

tower.

South of Larissa the landscape began to change. Jude

watched an irrigation machine like a giant stick insect

creeping over a field, and a tractor racing across another,

raking up a dust cloud behind in a brown jet stream. They

passed a meadow of green grass that rolled up to its crest

in a wave where a single cypress tree flew there like a

standard. It reminded Jude a little of Salisbury Plain in

England, and he half-expected a tank to rise up at the

roadside on war manoeuvres.

They drove on in an atmosphere that had warmed, Jude

thought, a few degrees. They came over a pass and to a

long, winding descent past walls with huge red slogans for

the Greek Communist Party. They drove by Eleonas, a

village of white houses above an escarpment of orange-tinged

rocks, and down through olive orchards with long

avenues of gnarled trunks. As they climbed towards

Delphi, the cypress trees lined the road like javelin heads,

and when they passed its sanctuary of Apollo, a place

pagans once thought of as the navel of the world, the light

was beginning to fade with the sun.

In Athens (Chapters 12 and 16).

Omonia.

They walked under a graffiti-soiled colonnade

where women in hijabs crouched around babies in

pushchairs, and there Jude noticed a sign above a door that

read ‘St Kolbe’s Refugee Programme’.

‘Let’s see if our spiritual cousins might help us,’ Jude

said to Mehmed. On the third floor in a dimly lit, spartan

office they were eventually given entry to the room of a

Father O’Toole, as the name read on the door.

‘Are you relatives?’ he said in the soft, arching lilt of

southern Ireland as he squinted a little at the photo.

‘I’m his pastor,’ said Jude. ‘We’re from Albania – and

you, Cork?’

‘Galway … You don’t look like a pastor,’ he said

smiling. ‘You look like a Romantic poet. Shelley or one of

them … or something.’

‘We have no union card. I could recite the Beatitudes to

you?’

‘That won’t be necessary,’ he said, laughing, and

pushed his lank, grey hair behind his ear. ‘And your friend

– is he Mafia?’ He glanced at Mehmed.

‘He’s a church elder.’

‘Oh, God save us from you Protestants. And you’d be

looking for your lost sheep here like a good fella, would

you?’

‘In a nutshell.’

---

Acropolis.

Now is not the time,’ said Mehmed. ‘Look there.’ Jude

followed the line of Mehmed’s sight until he saw four men

walking through the trees on the approach path to the

Propylaea steps and ramp. The second man wore a red

baseball cap and the first had an unmistakably thick neck

and a black bandana. ‘We did not lose them yesterday,’

Mehmed said, glancing up the steps behind him. ‘They’ve

picked their time and place, Jude, and caught us well, with

no exit. Come on … quickly.’ Mehmed pulled him

forwards and they set off striding up the steps onto a

wooden boardwalk. As they broke into a run, Jude heard

the heavy clump of his footfall passing by the weatherworn

stone columns, and it seemed to call unwanted

attention to them. Mehmed was propelling himself

forwards by the metal handrail. Soon, they were on a

gravel path running on to the citadel hilltop past the long

line of honey-hued Doric columns that formed the

towering Parthenon temple.

From ‘The Migrant’ © Paul Alkazraji 2019, Instant Apostle.

Read Chapter 1 of ‘The Migrant’ here:

https://instantapostle.com/2019/02/22...

Find copies of ‘The Migrant’ here: https://www.amazon.co.uk/gp/product/B...