H.L. Goodall Jr.'s Blog

August 24, 2012

A Message of Love and Thanks

Hello All. There is no good way to break this news, but we wanted to let people know as soon as possible. Bud passed away early this morning. He passed peacefully after a long, and at times, arduous battle with pancreatic cancer. While Bud’s time on earth is done, the words he shared, the love he gave, and the hopes and fears he recounted here, will live on here, in loving memory of his life, his work, and yes his experience with cancer. Nic and I hope that you continue to use this space to honor Bud and his work.

For the last ten plus years, Bud has been a virtual soul. He thrived on his virtual connections, which became especially important and crucial over the past year. The conversations he has had via email, Facebook, and with Communication community inspired, enlightened, uplifted, and more recently, kept him going, giving him something to look forward to each day, adding purpose and humor and joy to his life. Nic and I cannot think of a better way to honor Bud than to continue that conversation. Please take the time to memorialize Bud here in whatever way works best for you.

Nic and I would like to thank you all for all the support we have received over the past year. The outpouring of prayers, messages of support and encouragement and your love kept us going and buoyed us through this incredibly challenging time in our lives. While we sincerely appreciate everyone’s love and support, there are a few people we would like thank personally.

First, everyone at Four Winds but most especially Monica, Lauren, Gerri, Jan, Terri, Bonnie, Ashley, Dr. Robin, and Dr. Sud who guided us through the last year with such love and compassion and respect. We cannot begin to express our love and gratitude for who you are and how much you all have meant and continue to mean to us. Thank you.

We owe immeasurable thanks to Alyssa for her love, patience, positive attitude, and willingness to do whatever was needed, often without us even knowing it at the time, throughout this journey. She helped us move (twice!) cooked, cleaned, ran errands, and provided us with endless entertainment. She has been Nic’s rock, my extra dose of strength, and too often, the go to girl for us both when errands needed to be run, but Nic and I were too tired to go ourselves. She didn’t have to do any of the hundreds of things, big and small that she did for us this past year, but she did them all with love, a sense of humor, and tremendous grace. Thank you Alyssa.

And to Mac who was always here for us no matter what we needed. He helped us move. Brought us food. And was always ready with a strong hug when we needed one most. Nic couldn’t ask for a better friend and Bud and I are so lucky to have Mac as part of our extended family.

We would like to thank Angela and Anna for their amazing friendship. You opened your hearts and lives to us, accommodating our schedule and limitations, filling our time together with laughter and fun. Thank you for being your wonder funny, loving selves. And to all the other ASU folks who emailed, stopped by, and supported Bud and by extension, Nic and I over the past year, thank you.

Thank you to Amira, Bob, and Nick for spearheading the amazing tribute book Celebrating Bud. Your efforts and those of all who contributed meant the world to Bud and the book is something Nic and I will cherish.

We would also like to thank Stewart and Carl for your visits, your long, long emails, and the love and support you provided to Bud, not just in the last year, but over decades of friendship.

And to Vikki and Harvey, thank you so much for your love and support. Thanks for being our friends and having our backs when we also needed you to be our doctors. Thanks for always being honest and for letting me know daily that you were and are here for us. And especially to Vikki for always making me laugh when I wanted to cry.

The same goes for Kris, who always seemed to know instinctively when I needed a virtual hug or a funny message and never failed to provide both. I know you wanted to do more and to be here, but being where you are and doing what you do is so very important. We get that and we love you for it.

Thanks too, to the wonderful caregivers at Hospice of the Valley. Cheryl swooped in on a Sunday afternoon to get us started, addressing all of our concerns, helping us to make Bud comfortable, and giving Nic and I the support we needed at exactly the right time. Tammy has been so caring and attentive of our needs and Sean handled the more delicate matters of after-life needs with astonishing consideration for our needs and Bud’s wishes. Everyone at Hospice of the Valley, helped to make this last step in a very long process much less daunting and far less overwhelming that Nic and I imagined. We are so grateful for your help and support.

And finally, thank you to my family – Martha and Clarence (Nana and Pop), Rick and Jackie, Kat and Liz, Connor and Tyler and Ashley, Tory and John Carl and Rosa and Thomas for loving us, praying for us, and for knowing when to be here and when to give us our space. Sometimes, not doing the thing you want to do most is the hardest thing to do. I know that being so far away during this time has been so very hard on you all. Thank you for giving us the huge gift of making this about us and what we needed. I know it wasn’t easy for you all, but we love you all the more for doing it.

We were so blessed to have had the time we did. Our lives have been forever changed by the past year. Our little family had so many conversations, talked about so many important things over the past fourteen months and a myriad of small things that, at the time seemed so insignificant, but down the road will add to our loving memory of Bud as husband, father, and friend.

One of the things we discussed was what kind of memorial Bud wanted. And Bud, being Bud, of course said that he wanted to be buried in a cathedral, like Shakespeare or Chaucer. After explaining that wasn’t really a possibility given he was not British or famous (his local fame not withstanding) or knighted other than by the queen when he was five, or a member of the Church of England, he decided that what he really wanted was to be cremated and have his ashes scattered at Grayton Beach. Grayton Beach has special meaning for us. It was on a trip to Grayton Beach he and I realized we were in love. As a family, we spent numerous summer breaks, New Year’s, and Valentine’s days and part of both sabbaticals there. It is a beautiful, historic state park that has not changed in years and, we hope, will remain unchanged for a very long time. And in the little village of Grayton, one of our favorite spots, The Red Bar, beckons for those who want to raise a glass to Bud’s memory, if you ever find yourself in the area.

But for now, we ask that you join us in a virtual wake of Bud. Wherever you are, raise a glass and toast his life and his memory. And rest assured, he will be smiling down on all of us and in true Bud fashion, reveling in all the attention.

Cross posted on Bud's Facebook page.

August 15, 2012

The Best Good Thing We Could Hope For Today

Doctor Robin’s assistant called us around ten o’clock to let us know that the Doc was a little backed up and needed to move our scheduled appointment from 11:40 to noon. No biggie, but nice of the Doc to call. Last time we had an appointment I had complained about sitting too long in one of the clinic’s hard chairs, but that was back when I was still experiencing pain in my back. That she remembers is not only another sign of her commitment to humane patient care delivered with compassion, but it is also another sign of her personal commitment to me. To us. To our little family’s well being.

Small things like this note that itself was probably jotted down on my folder matter a great deal to us because they underscore putting the patient’s needs and feelings first. Sure, I can now sit comfortably in a hard chair due to the success of the radiation treatment, but Doctor Robin didn’t know that yet. So instead of risking that I might be uncomfortable, she simply consulted her notes and had her assistant make a phone call. No biggie, as I say, for the Doc or for the assistant. But the call and all it represented meant the world to us.

This meeting this morning promised to be an important one. I have been off the chemo for over a month and I have completed the radiation therapy as well. I am working diligently to reduce my dependence on the narcotics and steroids. I have ended my use of the short-term oxies and with tomorrow being my last day swallowing the measly one-half tablet of the steroid, I will shortly be totally steroid free. So, I am making better-than-expected progress meeting these treatment goals.

That said, today our agenda is to review my most recent blood work and scans and together - San, Nic, the Doc, and I - to discuss “the next step.” That discussion will involve an estimation of what else should or could be done - if anything - to alleviate any remaining symptoms (e.g. pain, swelling, etc.). It might also involve a discussion of additional chemotherapy treatments, depending on Doctor Robin’s interpretation of my CA-19/9 marker in relation to other existing data. So, as I say, this meeting promised to be an important one.

***

When you sit in one of the examining rooms at Four Winds there isn’t much to look at. The room is furnished with three small wooden chairs, a small round mobile stool unit on wheels, an examining bed that raises and lowers, and two desktops with the usual tools of the doctoring trade: cotton swabs, plastic gloves, bandages, and tissues. Behind the closed door cabinets are probably other medical trade devices, but I can only guess what they might be given they are behind closed doors. On two of the four walls are small, framed prints, both of which depict old town cobblestone street scenes. Both scenes have a light at the end of the street, an opening to whatever is on the other side of the wall, which, if you are an oncology patient and this is an oncology clinic suggest a hopeful secular and sacred end.

Ashley takes my vitals and we exchange some small talk. Yes, none of the meds have changed since our last visit, except in frequency of use. Yes, I still am eating and drinking well, and I have no problem with bowel movements. I am sleeping just fine. My blood pressure is checked with the standard arm device and it is fine. My temperature is checked with a digital thermometer and it, too, is normal. The saturation of oxygen in my blood is gotten from a clever little black device known as a pulse oximeter attached to my index finger; it is also normal. Ashley goes over these numbers with us and then exits the room.

Doctor Robin enters with a smile and we all hug. Our conversation focuses on a comparison between the empirical data from the blood work and how “good” I look, particularly when compared to how bad I looked the last time we were in this same room together. The really, really good news is that all of my organs are functioning just fine, and if you ignore (just for a moment) the CA 19/9 marker (which is up to 5800), there is nothing to suggest that I am in peril.

Doctor Robin uses her hands to frame my face, “this is the vital sign I pay the most attention to,” she says. “Last time you were in here I was worried because you looked bad.” She smiles, sympathetically. “You were in pain and it showed on your face. But look at you today.”

San and Nic explain that I had a curious sleeping spell over the weekend wherein I was literally out for 20 hours at a stretch and that 20 hours I was in a deep, deep sleep. “But on Monday morning sleeping beauty here” - San gestures to me - “ awoke and was back to his normal self.”

“Sometimes pain will do that to a body,” Robin explains. “When you are in as much pain as he was in the whole body absorbs it and the whole body has to get rid of it. So a long stretch of deep sleep is the body’s way of healing itself.”

“I did wake up a very different person,” I said.

“Now here’s the question for you today,” Robin leaned forward and took my hand. “Last time you were here you said you felt ‘diminished.’” Her eyes hold mine. “How do you feel now?”

“Not diminished,” I reply. We all laugh. “In fact, I’m feeling well enough to work on my class, which begins next week. I’ve also worked on some writing too. And I feel well enough to walk a few laps around the house; I’d go outside and do it but it’s just too hot.” No further explanation necessary for those of us who live in Chandler, where, for the past 10 days it has been over 110 degrees, with the local temperatures (meaning right in Chandler, not over in Phoenix, which tends to be a couple of degrees cooler) hovering around 112-116.

“That’s the best answer we can hope for,” she said. “Our goal has been to get you back to as close to normal as we can.”

“Well, if I didn’t know I have cancer, then all I’d have to complain about is my swollen ankles/feet.”

Robin says, “Yes, I can see that.” She examines my right foot. Since I wore the new “compression” socks my foot and ankle are not as swollen as they were, but it is still noticeable. “Sometimes a water build-up from the steroids causes the swelling, so let’s see what happens when you are no longer using them. And you are still recovering from the radiation, which can also cause swelling.”

We were done, except for the one marker that had yet to be discussed.

***

“Your blood marker has been all over the place and while, yes, it is somewhat elevated, there is no way to know for sure why. It could be a residual from the radiation. But as you know, this blood marker is not a precise measurement. What I’m taking as a more precise measurement is this marker” (she outlines my face again). “Which is why I think we just continue to live with it for awhile before we have any conversations about other treatment options.”

Whew! What a relief. This is just the sort of outcome that San, Nic and I wanted to hear. We have been discussing other treatment options and have come to the conclusion that we don’t want to undergo any further chemo (the recovery is too hard on me and detracts from quality time) if we can help it. That my face buys us more time away from treatments is not only a good thing, it is the best good thing we could hope for today and for the foreseeable future.

Hurrah!!!

***

A trip to the Four Winds Cancer Clinic would not be complete without a visit to the treatment side of the house and some big hugs with our oncology team - Gerri, Jan, Lauren, and Monica (we already hugged Terri). When they hear our good news they are ecstatic as well.

We exchange ribald humor about what happens when a fully functioning Bud gets a new bed (now that I have no pain in my back the clinic is ordering me an adjustable hospital-style bed), as well as about Monica’s newest rescue dog - another baby Basset Hound named Ruby.

I have such wonderful caregivers! We are truly blessed.

***

OK, so let’s look at today’s meeting this way (if you could see me, I’d be turning my head about 90-degrees). When you enter this phase of cancer it is less about treatment than about acceptance. Yes, I am doing fine. Today. I look good. Today. I am relatively pain free. Today. I am able to do most of the things that you and I consider normal activities. Today.

But it is one day at a time. That won’t change. And I hope to get in as many of those “one days” as I can before I leave the party. I don’t want to go, but it has been written somewhere that I must go, and so be it. In the interim I have had this profound year to review my life and gather around me those I care about and love for those final conversations that everyone should get but so few of us do. I’ve been honored with a book and visited by friends and family members. There is little left to say that hasn’t already been said.

Again, please don’t get me wrong. I’m still here. I’m not exiting any time soon, so far as I know. But that’s it, isn’t it? We never do know.

The only thing we do know for sure is that today is ours for the making, for the doing, for the loving, for the caring and sharing and daring. Offer up your prayers for others and open up yourself to receive the blessings of the universe. End each day with the personal heartfelt thanks to others that you would want to be said at the end of your days, and you will never end your days without that sense of thanks you wanted to say and you hope to hear echo through that long last night.

Today we got really, really good news. It is time to savor it. Tomorrow we are visited again by our ol’ pal Stew Auyash, which is a huge gift and a welcome one. Beyond tomorrow, who knows? We all face the same Milky Way when we look at the skies and the same questions for all of us still apply.

But that is the day after tomorrow. Today, what’s left of it, and tonight, what already beckons to us is waiting for our embrace, our celebration of life and of love.

You look good! What are you waiting for?

***

August 8, 2012

Other Than That I'm Fine

I have not cut back on some of the meds. Other than that I’m fine.

I mean there’s nothing to worry about. I’m doing fine. I’m also doing fine with the drug dosages too. I still take the prescribed doses of long-term oxy twice a day, Advil every six hours, B-12 and ALA twice a day, Prilosec once a day, and depending on the state of my “regularity,” and whether or not I needed to rely on one of those cutting-edge stool softeners and a powdered laxative, oh, and let’s not forget the magnesium.

I cut back on the painkillers: half a 2 mg. steroid twice a day (down from two steroids every 4 hours); no short term oxy unless I need it (down from two pills every 4-6 hours); two rather than three Gabapenetin every 6 hours). So, as a result, I have slightly increased “the level of pain I sit with” but it comes with noticeably clearer thinking, speaking, and writing, not as much tiredness, increased mobility, and my good ol’ bad Dr. Bud sense of humor.

The pain they’ve left me with isn’t bad. It’s more of a dull ache that is occasionally yanked and twisted by a particularly mean-spirited kitchen or bathroom or great room or car troll. Or at least that is what it feels like until I stand up or sit down.

That’s when the troll with the really dull knife, the one with the well worn serrated edges, slices through the middle of my already-scarred abdomen, ripping and tearing more so than cutting.

I really should sharpen that knife. If only it weren’t imaginary.

But other than that, I’m fine.

***

The pain can be as intense as it is sudden. Just as I begin to feel it and I go to make a noise - any noise - the intense pain sucks away my voice and robs me of my ability to breathe. So I sit down and take a little while to catch my breath, maybe thirty or forty loooooong seconds and then a few minutes to fully recover.

Other than that, I’m fine.

***

(unintelligible)

My feet are swollen and yet I have almost no feeling in them,

They resemble cartoon piggy feet,

The kind that swell up suddenly when hit with a sledgehammer,

Only there wasn’t a sledgehammer.

This isn’t a cartoon,

And I’m not a pig.

But there is this clue:

My feet are swollen and yet I have almost no feeling in them

Other than that, I’m fine.

***

I do worry about our planet. Hard not to when today in Chandler, Arizona the triple digit parade of hot summer days continues. We should hit 114 degrees later this afternoon. It’s miserable. And I’ll punch you in the face and chase you down the street with my cane if you tell me “it’s a dry heat.” [image error]

Complaining about the weather is about as useful as denying climate change. For years, change deniers said obvious things like that and it gave them the weight of truth as if drawn from a body of scientific work that was supported by a general philosophy. Well, deniers, according to the NOACC, July 2012 is the warmest July on record ever. And that is the weight of truth drawn from scientific work supported by a general philosophy that nobody can deny.

Here’s the irony. If I tell someone my feet look like alien feet due to how much they have swollen, chances are good that 8.25/10 people will tell me it’s the heat. And then they will tell me that if I get back inside, elevate my tootsies, and stay out of the heat I should be all right when the weather cools back down. Then, if I ask the same people whether they accept that global warming is responsible for the high temperatures this summer, chances are about the same - 7/9 (I lost one to a long bathroom break) - that those polled with disagree with me.

Hmmm. Let’s see. Most Americans are perfectly willing to accept a claim that links my swollen piggy feet to global warming, but these same adults are then unlikely to support my claim that global warming has many negative effects on the planet.

‘Scuse me, but aren’t my feet on this planet? Where are my painkillers?

Oh, and aside from that, I’m fine.

***

You and I are on the right side of this scientific narrative. You and I agreed with Al Gore and been on the side of the environmentally righteous even before that (I, for example, was present and picking up trash on the side of the road for the very first Earth Day in 1970). Because then, like now, most boys and girls get out of school to participate in these outings. And, because then and now, the whole point of the exercise had little to do with learning about our environment and everything to do with … er, learning about boys and girls.

But regardless of how we got here, to this explanatory pause in the storyline where women and men of science who have worked on these questions for decades and who take seriously the empirical data as well as anecdotal evidence that captures the human side of the story, and we find that in addition to what we already know and fear, there are some newly shared fears that make what we are facing that much worse.

94% of Greenland melted in Juy. This summer’s July. 94% in 31 days. Think of snow melting, ice caps melting, ice melting.

Think of your own feet. If that’s what it takes.

But we may be too late. It’s not as if we are actually doing anything about it, are we? Do you see a Salvation Army-type collection cup attached to old men in “I’m Saving the Planet” uniforms? Would collecting money solve the problem?

Or have “we” - the greedy self-centered Wall Street corncobs and old boneheaded climate deniers - finally succeeded in creating a Big Problem that we have now moved past the threshold of what science can do to solve?

In other words, have we something much worse already loosed upon the world? Something that “all the king’s horses and all of the king’s men couldn’t put back together again?”

***

You feel like breaking into a commercial. You know, like the Gieco ads that break the frame by taking a simple everyday occurrence - your cable bill - and stringing out a story that ends up in the least likely place a narrative could end up. Hold that curiosity …

So when you get depressed due to global warming and feel you are no longer in control of your planet’s atmosphere …

You see a show on cable about “Doomsday Preppers” that convinces you that the way to regain control over the global warming narrative is by creating your own Doomsday shelter with its own air and water supply, a filtration system for anything coming in or going out of the shelter, and three years’ supply of food, water, and supplies.

You move into your shelter and wait.

The Handbook of Doomsday Preppers says you will feel better when a disaster strikes.

You continue to wait.

Three years pass. You’ve grown an impressive beard and eaten all of the chocolates.

The blue planet grew warmer and the ice caps melted, as per projections. Major cities flooded and world economies collapsed, as per projections. Migrations of people to the high country and to the upper Midwest led to a very different political map. Local economies trumped global economies. And so on.

Finally, an asteroid the size of a panel truck moving like super-charged giant shot put across the Milky Way takes out your shelter. All that is left of it is a large black hole and a few random items of food and clothing that within the hour are gone.

You are declared dead.

You aren’t dead. You’re not exactly sure where you are. Or who you are. You may be a poet. Or a scientist. Or a storyteller. Some Big Whoosh came along when things got dark just before the panel truck hit and the last thing you remember is that everything happened so fast. Was there a light? Maybe. You don’t recall from this end much of what happened when you left that end. There was a light in the woods … or did you imagine that?

But, regardless, you find that you are trying to convince the same people you once tried to convince about the truth of global warming that you were right.

Only difference now is that they believe you.

But it’s too late.

You just shake your head.

Other than that, yeah, I’m just fine. Just fine.

***

So is the heat in your oven. Put you head in there, won’t you?

I asked 10 people in what must be one of the most convenient samples I could concoct. The .25 refers to a child under the age of 12, probably under the age of 6 to tell the truth. But she nodded. And a nod is as good as a wink to a sidewalk social scientist. Points awarded to anyone who can name the singers in those two songs.

July 31, 2012

The Secret of Time and Immortality at the End of July

Tell me the truth: Has it been a whole month since we all last shouted “Rabbit, Rabbit, Rabbit!” for good luck? Are we really entering August, 2012?

The short answer to both questions is “yes.” Yes, it has been almost a full month since our last happy three rabbit shout-out, and yes, we are entering what will be my 15th month - our 15th month! - of living life as a cancer survivor. I am grateful, profoundly grateful, for that time.

***

No surprises then. As a Stage IV Pancreatic Cancer survivor, time is on my mind but not necessarily on my side. In part, this blog about my cancer is necessary because it represents unfinished narrative business and, as you know, I try to work through issues by writing to learn about them so I may share what I learn with others.

And in part I write about health, my cancer, our family, and “what it is like to live this way” because what began as “I can” became “I must.” I am still alive. I am a writer. I write about “the truth of my experiences.” I believe that once I decided to use my autoethnographic background to write about my illness I bought a little time to expand my life narrative and, as a result, I modified my relationship to immortality. Those extra blank pages are there for a reason. They represent empirical work left undone. They also call for an imaginative resolution to the narrative, a way of bringing into the light the dying body that will be left behind as well as the birth of a new narrative when the Great Whoosh arrives.

These are recurring themes that I seem to return to at the end of each month. Given the pain I’m still working on there are times when I have wanted to be “done with it,” but it’s pretty clear that someone or something isn’t done with me yet. Time, then, is one unresolved ambiguity I think and write about when I pause from known routines of the day to consider “where am I?” in this larger mystery, this larger mystery that is my life and that is heading for a resolution not too far up the road.

If I could pull The Big Book of Bud’s Amazing Life out of a magician’s top hat, by all rights I ought to be coming down to the last few blank pages of my personal narrative. Yet, when I consider the theme of time in relation to end-of-life narratives and imagine a denouement wherein immortality figures into it, I find I am closer but not close enough to figuring out my part in this divine mystery. And that feels okay. Okay for now. I’m not done yet. That much is clear.

What does happen instead is that The Big Book of Bud feels much lighter to carry around in my head, while at the same time I know deep in my soul that it’s up to me to write down what will ultimately appear there. How what I write about it is within my purview but how it will be remembered is beyond my control, a duality that has been the case since I began writing my life story and sharing it with others.

Or put differently, I accepted that challenge to write as true as I could about my life in the context of others, about the awe and all of it, about the hard stuff and the funny stuff and even the ineffable stuff, from the origins of a particular narrative conflict or desire all the way through to the final resolution. In all of those writing experiments I had some control over how I represented realities and evoked lives and scenes and outcomes. How I may be remembered for them, whether or not they continue to serve as good examples for students or inspire other writers to find their own voices or provide phrasings that find their way into the work of other scholars or the speech habits of everyday citizens - well, I have no control over any of that. But I know that will be the measure of my own immortality as a writer.

As a person there are other measures of my life.

***

Right now I am still working on the rough draft of that final resolution, and I have learned a few useful things about time and immortality that will no doubt make it into the final draft. My musings on time in relation to writing taught me that how others remember us and pass those memories along is as close as we get to immortality. I’m perfectly fine with that version of the story because any other version of a “life everlasting” is just too exhausting (talk about “a never-ending story”) as well as being - IMHO - spiritually confusing.

Do you really want to live forever? Or would you rather be remembered forever? Remembered for what you have done, for what you’ve contributed to the common good? For the poetry that changed a life, for the story that inspired others, for one speech - choose your favorite one and paste it here - that still resonates down the ages? Or how about the song you sung to a child? Or the food you donated to the poor? Or the bed you provided in a storm? Or the clothing you collected for families devastated by a natural disaster?

My point is a simple one: It is better to be remembered for what you’ve done when what you’ve done is not only the right thing, but the thing that in so doing revealed your faith by a fine and quiet example, by the exercise of good deed as well as by good word.

***

Do you trust your faith, or for that matter your science, to have prepared you for that final exit, or not? If you’ve lived a good life and, with admittedly the usual anxieties all present and accounted for, do you genuinely look forward to evolving into what waits to be written about your future?

Do you look forward to that part of the holy/scientific narrative that guarantees a resting place for your soul, a cosmic use for your energy, to what has been promised to us by God, the prophets, and his messengers?

When you consider time and eternity in this way, as a way of being remembered, isn’t the idea of immortality of any other kind best left behind, along with your earthly body and that tattered old Superman suit?

***

Friends, it’s the last day of our 14th month and tomorrow we will awake to a 15th month and a big shout-out: Rabbit, Rabbit, Rabbit! I will give thanks for another day of life. I will use my time to work on my life story and not worry too much about immortality. I will do what I can to make others’ lives better, happier, and, as far as it is possible, more interesting.

It’s going to be another day of life done one day at a time, but one day at a time is all we ever have. One day at a time, then, is a quiet reminder to take seriously - but please not too seriously - our selves. It is easier to lead with a smile and by a way of being in the world that makes others smile as well as seek your counsel.

The stories they will tell about you and me are unlikely to begin with “Jesus later related this story to Luke, who labored four or five days before deciding it could not be worked into an instructive parable,” but they will be told. In time they will add up. Over time they will become what you and I leave behind, worthy of being retold and enjoyed or just forgotten.

Let’s use this timeless energy for immortality to make out of the everyday a richer more poetic narrative - a narrative about who we are as creative spiritual beings; about us as women and men on a noble quest for meanings, for justice, for a way of being in this world that prepares us best for whatever comes next; and then let’s devote part of each day to figuring out what we must do to achieve our starry night destiny, our own personal narrative’s most satisfying end.

***

July 25, 2012

Mystery Loves Company: What the Good News Is and What the Good News Means

Yesterday San and I met with Dr. Robin to listen to and talk about the results of the most recent CT-scans of my chest and abdomen, my labs, and what should be our “next step.” We drove to the Four Winds Cancer Clinic and agreed that no matter what the news might be, we would take a little time before agreeing to reenter chemo.

We figured chemo might be the only answer for the pain I was experiencing in my abdomen. But chemo has a downside, many downsides really, not the least of which has been a “loss of self,” which is a label I use to describe the longer and longer recovery time from a round of chemo, during which time I am basically “Dr. Bud in the chair” over there and not much else.

But not becoming the resident broccoli in the room was only one of our “end-of-life/quality of life” concerns.

Readers of this blog know that prior to that meeting with Dr. Robin, I was worried about what the scans might show, given the surprisingly sharp pain I was experiencing in my abdomen throughout the day and the strange spasms that woke me up at night. When a concern about pain emerges in our narrative it is always accompanied by a corresponding concern with time, as in “how much time might I have left?” It’s not a question with an answer. At least, not usually a good one.

***

Given that I am a lucky 14-month survivor - which, believe me, we count as a major blessing - time and pain are constant sources of ambiguity around the corners of every conversation we have about making plans for the future, even when that future is tomorrow or next week or next month.

Let’s agree without getting whiny or weepy about it: Fourteen months of using every medical tool to fight pancreatic cancer is a long time and it has been a hard fight that we know one day we will lose. Learning how to balance the fear with the fight is as real to me as fresh hot coffee first thing in the morning. And there is a good reason for attaining this balance. As my pal Richard has explained it to me, learning to embrace my fear is a good thing because it puts the “fight and fear of losing the fight” into a more balanced and therefore useful perspective. Richard writes it this way in an email: “better be afraid my friend, than slack off and lose.”

Fear of losing keeps you in the fight, looking for an opening, moving out of danger when you see it coming, rope-a-dope in the hope our enemy punches himself out, and it reminds me of all of that hand-to-hand combat manly stuff so familiar to Richard but mostly alien to me. My tools are made out of words, my stories are made out of what my autoethnographic self makes out of the meaning of our journey. But I do learn something valuable from what Richard teaches me about fear, or maybe I’m just reminded, that fear can be a good thing in a fight for your life, as it does prevent me from giving up or giving in. I don’t want to die. Not yet. And I’ll fight like the man I am right up to the end.

So no, my dear friends (this upcoming line made Carolyn Ellis chuckle), I’m not yet “circling the drain.” I was just afraid. But the words I heard from Dr. Robin helped me see that - again, against all odds - I was doing much better than I had feared. We were still good for the longer fight.

***

Time and pain are two strands of my ongoing narrative. I’m pretty sure I know, unlike Forrest Gump with his box o’ chocolates, “what [I’m] gonna get,” which will be the one chocolate left for last at the back corner of the Godiva box, otherwise known as “how my story ends.” But I’m not there yet.

And neither are you. Fifteen months is on our immediate horizon (August) and sixteen months (September) cannot be far behind. I am reaching out for September because on September 1st our SEC-loving football family can watch ‘Bama against Michigan, and the following week I turn 60 on September 8th.

These are short-term goals, but they are also a reminder that accomplishing them requires continued due diligence on both my narrative and the meds, for I need both of them to work for me as I continue the good fight each and every day. Even then, there are no guarantees. Not for any of us.

Example: Only this week it was 17 months and the Great Whoosh came for a true American hero, Sally Ride, who also died from pancreatic cancer. News like that - even though I know every cancer is different and there is no way to know for sure how long anyone has left - nevertheless tends to dwell in my head like an unwanted guest.

I think I know something of Sally Ride’s journey, and, because we shared the same cancer, something of her pain. In my head I counter the negative energy of learning about her death and that 17-month timeline by putting a twist into a popular song: “And when the pain comes … (I’m hearing “When the rain comes” from “Paperback Writer”) I run and hide my head.”

***

But the good news was I don’t have to hide my head. The scans from my neck to my hips showed only what I hope for the Middle East - “stability throughout the region.” [image error]

As Dr. Robin told us with her characteristic kind smile and in no uncertain terms, “I couldn’t be more pleased” with these results:

No new growth on the “existing but dormant” tumor on my pancreas and the smaller spots on my liver;

No sign of any spread of the cancer throughout my chest and abdomen;

No evidence of any activity (other than shrinkage) on the targeted tumor pressing against the nerve sack along my spine - a long way of saying that the radiation therapy worked;

No advance of the disease to my lungs or lymph nodes (a very good sign), nor any negatives from my blood/lab work. My organs are still functioning normally, including my kidneys (also very important). There is some minor evidence of plaque along some of my veins/arteries, but nothing to worry about as “we all have that.” And my heart is still beating strong and regular.

All good. All good. All good! Amen! Amen!! Amen!!!

***

The pain issues are now what we are focusing on. Ridding my body of as much pain as possible means a return to a quality of life that, while not what it was when I was in “remission,” at least allows for more mobility and a little R&R outside of the house. Also, the pain I’m experiencing now is related to (1) the residual effects of radiation, as it is still fighting off the cancer in my back and near my spine, and those effects won’t last much longer; (2) the continuing effects of the hairline fracture on T8, and that fracture should heal over the next month or so; (3) the timing of my meds; and (4) the associated body ache miseries associated with my age (oh well) and spending so much time in my recliner.

To address these concerns we agreed to modify the meds schedule so that I slowly rid my blood of the steroid and the Gabapentin in favor of a slightly higher dose of long-term Oxy and the reintroduction of good ol’ Advil to my regimen of helpful pills. I also will walk a bit more, sit a bit less, continue to take comfort from good books and movies, and combat the Blue Meanies (see below), always with a little help from our friends.

***

That said there is something else I need to say. If I scared any of you with my last post, forgive me for that was not my intent. Please know that I was only fulfilling my promise to you early on to “tell what it is like to live this way” with cancer. And it’s not always going to be a pretty tell.

Some days I am visited by not just abdominal and back pain but by what Beatles’ called the “Blue Meanies,” or music-hating clowns who represent bad things happening to good people in the world. When visited by these cancer-bearing goons, the uncertainties I have about life give into fears of death and dying, and when that happens it’s like a sledgehammer crashing into my brain and through my protective narrative threshold.

Writing about those fears is also part of my therapy. I know I can’t control the disease just by writing about my fight against the Blue Meanies, but I write about them to control my fears about the disease, to gain a narrative grip strong enough to get me back “up” again. And hence, maybe that is why I am now often hearing the lyrics of songs or snippets of poetry or lines from old movies playing in my head.

Never underestimate the power of fear to feed anxieties about cancer (or, I imagine, any chronic disease). But also never discount what you and I have to combat it. Which is to say never discount the power of the human voice, the touch of a human hand, and the love in a human heart to lessen the anxieties. And with that lessening of the anxieties, a lessening also of the deeper fears that drive them - a loss of time, a loss of self, a loss of relationships with those we love, and a loss, ultimately, of life itself.

I cannot tell you how our talking with Dr. Robin yesterday changed the fear narrative that had darkened our door since the pain kicked me in the guts at 3 a.m. earlier in the week, a pain that also cut like a sharp knife into those same guts every afternoon. By talking about it, by seeing the pain in relation to what else was going on in my body and what steps we might take to lessen its severity, we created a new plan.

So it happened in that small examining room with San holding my hand that the fearful theme we came into the clinic with - “he feels for the first time like he is dying” - was spoken out loud. And it was in that same room not minutes later, enabled by honest talk, the human touch, and real data drawn from tests on a body that somehow refuses to die, that our fearful theme of impending death was transformed once again into a renewed life.

I haven’t felt such a heavy weight lifted from us since last November, when, for a brief but happy time we were in “remission,” complete with quotation marks, because in Stage IV any “remission” is only temporary.

You know what? I’ll take it. So will San and Nic. Because “temporary” is all we get in this life. That’s all we yet know of the plan, Stan: We are stardust, we are golden …

***

We left the Four Winds Cancer Clinic but not before hugging our oncology team and sharing with them our good results. We didn’t get a Happy Dance but we didn’t need one, either. With this team we are already dancing.

We are not complacent. But neither are we narratively trapped in a temporal unreality composed in fear and irrationally bounded by our own escalating anxieties. One day at a time we tamp it down. One day at a time we deploy our strong counter-narrative that begins and ends in gratitude and prayer.

This doesn’t mean we have entered some kind of mindless blissful state where, as Forrest Gump’s Mom puts it: “Stupid is as stupid does.” We still have the necessary everyday concerns about how my 59-almost-60 year old body handles aggressive chemo, TrueBeam targeted radiation, and a box o’ meds to rival Forrest Gump’s box o’ chocolates. “You never know what you're gonna get" is true enough, but it is only one “true enough” truth and there are so many larger truths yet to learn.

I may not know exactly what I’m going to get, but least I know some of the story I’m likely to perform. Some day in the future as I lay dying (had to get Faulkner in - another voice in my head) my physical body will be all that is left that other people see of Dr. Bud. But there is a bigger mystery about my energy being reborn, not so much about getting back up again as about being dispersed across the universe, about an awaking of a new consciousness on the other side of this ending that I will become part of, and that will be whatever it is. As Eric Eisenberg pointed out to me in an email this week:

Seen on a cosmic scale, the pattern becomes clear—birth, death, birth, death, birth death—not just of people but of every carbon-based creature on the planet. Vertical, horizontal, vertical, vertical, horizontal. Set ‘em up, knock ‘em down. The rhythm of life on earth.

In yoga they teach that the self is a swinging door, breathe in and it’s you, breathe out and it’s everything else. Then in again. And so on and so forth.

Consider a whirlpool in a river, or a wave in the ocean, both there and not there. Form persists, but the water always changes, energy flowing through form.

The mystery of human life is that while all this is undeniably true, what is also true is that incredibly the current that flows through each of us has eyes and ears and touch, and senses kindred currents in all other living creatures. Mystery loves company.

***

“Mystery loves company.” Truly a profound statement. I already knew from the B-movie sage Buckaroo Bonzai, that “no matter where we go, there we are.” But Eric’s profound insight is no B-movie. It is pure poetry for where this story is headed. Mystery loves company … and so we will never be alone.

The Great Whoosh will swoop into the room and one swift last breath later my body will no longer be of concern. The pain will be gone. And - this bit makes me smile - I won’t care. Why would I? I won’t need it anymore.

My body will be cremated and my ashes will be scattered into the air and sea at Grayton Beach State Park in Florida, at the exact heavenly place on our intergalactic map, an intersection both real and imagined, where San and I fell in love and together changed forever our lives.

There will be music and dancing, stories and laughter and love enough for all of you, after that fact. But not just yet.

And for the “not just yet” part of our ongoing storyline, only this: Mystery loves company.

You know what I mean? Of course you do.

***

July 22, 2012

Sunday in the Sage Green Chair: A Turn in the Pain, My Life, and the Face I See in the Mirror

I awoke early this morning - about 4:15 a.m. - because I moved a little in my recliner and that set off a sharp pain in my guts. I grabbed my iPhone and switched on the flashlight app to find the prescription bottle of Oxycodone and bottled water, shook out two small white low dosage pills and tossed them back with a swig.

In about 15 minutes or so the pain gradually disappeared. Once it passed the threshold going down into the “no pain zone,” I could breathe deeply again without feeling as though I was ripping my stomach apart.

It was now 4:52 a.m.

***

What to do? Given that sleep was no longer possible and I didn’t want to wake San (she fell asleep on our couch an had a nice little snore going on), the answer was either read something or write something. I figured I still had at least an hour before turning on the coffeemaker was a viable option - I try to let San sleep at least until 6:00 a.m. - and it was still dark outside.

“Darkness, take my hand,” comes into my head for no reason I know of, but then I remember it is the title of a good Dennis Lehane mystery novel. Lately these random titles, lyrics, snippets of poems, and other fleetingly disconnected words and images zoom in and out of my head.

I have no idea why. I figure its just part of reviewing my life before dying. Not a bad thing at all, so long as the review moves slowly. [image error]

***

To enable my best memories of our lives together, San loaded our photos from travels and celebrations and times with family and friends that were about nothing in particular, but show us being us, into the Apple TV system in the living room. When we are in between movies or shows or I am just content to sit still and watch the TV screen instead of the computer screen, I get a family-friendly version of images that trigger what Ernest Becker calls “an inner newsreel” (1962).

The “inner newsreel” is a powerful idea that, when coupled with his “denial of death” goes well beyond my more personal and admittedly pedestrian use for it. But I don‘t think Becker would mind. For him:

“individuals' characters are essentially formed around the process of denying their own mortality, that this denial is necessary for us to function in the world, and that this character-armor prevents genuine self-knowledge.”

For me, it is no longer possible to deny my own death. I know the trajectory of my cancer. I feel the increasing levels of pain. We know the disease has spread. So it is that I now awake every day in a surreal and unfamiliar place - the existential space for making final, irrevocable choices - where I stand without the “character-armor” or any real ability to deny my own mortality, but find that I am newly open to a kind of self-knowledge that, over the past 14 months and still counting, is in fact occurring.

I did not want to die of cancer. Hell, I did not want to die at all. But once diagnosed with this damned deadly disease and left to live for an uncertain period of time with few uncertainties about where this narrative had to go, I wanted to learn from cancer and to share with others what I had learned.

I wanted, if nothing else, to understand myself not as someone defined by cancer - every cancer patient says that and means it - but instead by what I could learn about my own death and about the process of my own dying. Why? Because for some reason I cannot yet name, I think that is something I’m supposed to do, and to learn about myself and this earthly life, before I move on.

***

There is no doubt that I have been profoundly changed by my cancer. We - my beloved family - also have been and continue to be profoundly changed by my cancer. We are learning not only how to live with it but how best to die from it. And that is a question that - believe me - I never before wanted to explore.

Here’s a short but illustrative story that you, too, may find useful.

Back in 1985 or maybe it was 1987, there was one of the legendary “Alta Conferences” for organizational and ethnographic scholars way up high in the beautiful mountains of Utah. One feature of the conference was some “walking around” time, a time for new friendships to blossom and for the contemplation of our papers, as well as just hanging out enjoying each other’s company in this peaceful mountain paradise.

On one of our breaks for “walking around time” I struck up a conversation with a remarkable scholar named Lyle Crawford, a Buddhist who later achieved some notoriety - he made the cover of The Chronicle of Higher Education - for “giving back” his tenure. He was and is a man who emits an undeniable inner joy. He lives simply (one knife, one fork, one spoon; one bicycle; etc.) according to his Buddhist beliefs and gives away most of what he earns. Three years ago I learned that Lyle had retired to a Buddhist retreat in China, and his email to me about it was as cheerful and life affirming as ever. He was, I knew, preparing himself for a “good death.” Little did I know at the time that shortly I would be doing the same thing.

Zoom back to 1987 or 1985, zoom in to Alta, zoom in further to two middle-aged white guys talking about death. Earlier in the day Lyle had presented a paper - the “crocodile narrative,” a moving surreal account of a Peace Corps volunteer whom had died swimming across a river in Africa, and whose last words were - as Lyle put it - a “series of Ohs, as in O-o-o-o.”

Lyle had written quite a story. He had written about a sudden violent death in such a way as to make death a character that can only be understood in retrospect. By this I mean that as you read the story you have no idea what will happen. You are in Africa. It’s hot. The volunteers decide to play a game that involves swimming across the river. While they play their game more and more native Africans line the riverbank, watching, but no one present thinks to ask them why. They should have. The natives were there because they knew the river and because they knew that crocks owned it. What they could not figure out was why a group of white people was swimming, making noise, and otherwise disturbing the afternoon with a silly game. So they came to watch. Did this white boy maybe possess some juju that would dissuade the crock? Or, failing that, had this fellow prepared himself for death?

The Os at the end of the last sentence he would ever speak are ambiguous. We don’t know what he thought or how he might have been prepared for his own death. All we know is that he died in the water, one Oh-o-o-o after another.

***

The story was and is instructive. Without overt discussions of weighty issues involved in the death of a colleague, the story Lyle wrote speaks to a denial of death, to hubris, to the everyday belief that nothing so bad will happen to us.

Ultimately, the story as a story speaks volumes to our inability to know what to say or do when death visits us or someone we love or even someone we have just met. I was humbled by the hearing of it, and curious about his motivation to write it. So I asked him. Lyle smiled and said, simply, that it was written out of his own need to prepare himself for his own death.

I don’t remember what I said in reply, or if I said anything at all. I know only that I walked away from that conversation in a kind of narrative daze that was to become how I remembered Lyle and his story. I was clearly in denial of death. I just couldn’t handle the weight of it. I wasn’t ready for it.

Or so I told myself. But there was always a cruel echo that followed my empty words that were all about the denial of death as those words silently moved through my brain and body. “I wasn’t ready for it,” I’d say to myself as my inner newsreel replayed the crock story. And then, as if on cue … Bwahahahhahahaha!”

***

Indeed. Who among us is ever ready? Who among us has done the soul work, the end-of-life narrative work, to prepare ourselves adequately for our own death? Oh, I know what some of you are thinking. You are thinking that as Christians (or fill in the blank here for your faith tradition) you are already saved. Maybe you have done the homework, memorized your sacred text, gone a mission, brought others to the teachings of Jesus or Moses or Mohammad or Joseph Smith or Buddha or whatever. That’s all to the good, right?

Yes, probably. But that is not the same thing as becoming prepared for your own death. You may have ensured an afterlife, I don’t know about that, but it's the end of life that we are talking about here. The process of the body dying and the coming of what I can only think to call “the Great Whoosh” that provides a conduit between this world and whatever happens next.

I write these words out of a genuine curiosity. I don’t have an answer. Not yet. What I do have is pain. What I do have is a diminished capacity to do a lot of things you take for granted and that only months ago I did too. What I am doing is dying. It’s not easy. It’s not pretty - I certainly do not have a face made for crying. And it hurts. Even with the drugs, it hurts.

And then there is this: No one tells me anymore: “hey, you look good!” That is because I do not look good. I look in the mirror and what I see is a man who has aged in obvious ways over the past month or so, a man who is growing a Hemingway-esque beard because shaving my whole face is more of trial than a triumph, particularly when (maybe it's the drugs) I forget one side or the other. What I see when I look into the mirror is a darkness below my eyes, eyes that no longer shine, eyes that quickly look away from my own eyes, my own face, my own self.

What I see is me beginning to die, from the eyes that no longer shine all the way down my badly aching guts to legs that have lost muscle tone to feet and ankles that swell into pig-like forms that I no longer feel due to the numbness of chronic neuropathy. And this is me, whining like a man I never wanted to be, and I apologize for it, but there it is. To whine at least once in a while is to be expected I guess; it seems to be part of the process.

One more thing. I, too, have been guilty of, if not exactly a denial of death, then certainly in something like a belief I was entitled to so many years, that I still have work left to do that would have stalled the Reaper, or any one of one hundred and one other black-and-white Dalmatian excuses that sounded pretty good when I said them, but that really only marked me as Everyman: glad to be alive and in fear of dying. As I have said before in this blog and elsewhere, one of the most profound things I’ve learned is that “God jokes with his best ones.”

***

I have been profoundly challenged by the fact that I am dying and that my acceptance of it is a necessary and even a good thing. It’s not a challenge to the death I so long denied would happen to me, but instead it is a feeling of moving toward something else. As a result I know in my heart, in my soul, that I am still evolving in some significant ways: I view every day as a gift and a blessing; as a result I focus more on the positive, on helping others, and there is a new spirit of gratitude and forgiveness that releases me from the firm hold of my old evil friend - the ego.

The key to my liberation from a fear of dying is to move away from the totalizing concern for the loss of self that death represents. San’s placement of the pictures from our past, real images to guide memory, does precisely that work. Or at least gets the process started. I see Nic and Alyssa smiling for the camera on Hamilton High School graduation day and I focus on them, their relationship, and their experiences in high school. I see our niece Tori Bray Hastings learning how to properly can vegetables in Aunt Rosa’s abundant kitchen. And I see San and a guy who looks a lot like me - thinner younger … yeah that guy - holding hands in front of a 15th century stained glass window at a college in Cambridge. Each one of these images reminds me of happier times. They also encourage me to think outside of my self.

The pain reminds me that what I have accepted, what San and Nic and (I hope) others have accepted as well, is that from here on out our journey through Cancerland is all about managing the pain. Which means staying ahead of it. Which means never saying no to good ol’ Oxy and his friendly gang of associates, including the anti-seizure med, Gabapentin, and the steroid Dexamethasone.

To the painkillers you can add the rest of my regimen of pills: the twice daily blood sugar; the once a day blood pressure; the twice daily B-12 and its partner “Nerve Shield”; the once daily Magnesium to accompany the stool softener and liquid Miralax mixed with Cranberry juice … and then here comes another lyric into my brain, this one from Donavan Leitch’s 1973 release “The Intergalactic Laxative” on Cosmic Wheels:

Oh, the intergalactic laxative,

Will get you from here to there.

Relieve you and believe me,

Without a worry or care.

If shitting is your problem,

When you’re out there in the stars,

Oh, the intergalactic laxative

Will get you from here to Mars.

Fourteen months ago I didn’t take any pills other than a daily vitamin and half an aspirin. Fourteen months ago I wouldn’t have laughed at Donavan’s lyrics quite so loudly. But I’ve had fourteen pretty good months to do a lot of the early work of dying, and for that time - and whatever time we now have left - I will be forever grateful.

I’m not done yet. Not yet. Nor am I dissuaded from my belief that I am preparing for whatever come next surrounded by a profound love and beneath the cosmic stardust that someday I hope to rejoin. Final lyric, from Joni Mitchell, zoomed in my head as it was sung at Woodstock by Crosby, Stills, Nash, and Young:

Well maybe it is just the time of year

Or maybe it’s the time of man

I don’t know who l am

But you know life is for learning

We are stardust

We are golden

And we’ve got to get ourselves

Back to the garden …

***

July 15, 2012

Two Unwinnable Wars and the Lack of an “Exit Narrative”: Harper’s Index Unfolds the Costs, Chekhov’s Gun Remains on the Table, Which all Leads to Asking What is a “Good Death,” and, Thankfully, then We Get Some (Interrupted) Rock n Roll Music

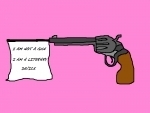

I place a Para Ordinance SSP 1911 pistol on the black coffee table.

It is a fine weapon and it is loaded.

When I teach my narrative writing seminars I begin with the Aristotelian or “classical” approach to structuring a good story and move through a history of literary innovations – structuralism, post-structuralism, postmodernism, and so on. My aim is to reveal to students the importance of craftsmanship to a well- told tale, where “craftsmanship” means how each part – the scenes, acts, characters and their attributes, and (if we are reading a masterwork) how every word spoken or silence retained, and of course the gun on the table contributes to the whole.

For those of you who do not dwell overly long in the narrative hot house of theorizing stories, the short version of why I might do something like that to otherwise very nice and intellectually curious students is pretty simple: How a story is told – its narrative structure/anti-structure – is a useful critical tool whether you plan to become a writer or a smart ass. It allows us not only to see into the intricate inner-workings of a story’s construction, but also to explain how a good story “works” (or doesn’t quite, or doesn’t at all) and why one story is or may be – using criteria drawn from the theory – better than another.

There is a useful analogy between the body and the story when teaching narrative structures. One of them is that a story’s structure is like a human skeleton: The bones are made to support the body (of the tale) and with some initial motivation to the nerve center in the brain and its release of the spine into action – there’s that need for a conflict to drive the action again – we find that the need to complete the narrative, to satisfy that conflict, becomes the vehicle that moves the skeleton/story forward.

Walter Fisher’s two criteria for evaluating a narrative extend the analogy between body and story: (1) it hangs together as a story, and (2) it rings true. The skeleton is what makes the story “hang together.” How well the story satisfies the initial conflict throughout the body of the tale, how artistically and pragmatically the narrative moves scene by scene through its trajectory to its ending, is how it “rings true."

***

That said, there are as many novel ways to meet the evaluative criteria for a good story as there are active imaginations. Some authors mimic older forms of storytelling, from the proud high-stepping prance of retold Homeric epic poems to the stylistic romantic elegance of greater and lesser forms of belles lettres.

Other writers do their own versions of a Geertzian “blurred genres” by combining two or more forms – say the scholarly fieldwork report and a class-based murder mystery with betting, blades, and fighting roosters set in Bali. Still others use what they know about the formal requirements for this or that literary form and/or style to “break the rules” of a genre and in so doing comment both on the fit of the subject as well on the genre itself.

***

The Harper’s Index format – a creative format for relaying facts against facts in a minimalist, ironic fashion – may also be used to “tell a story,” albeit in an unusual way. But between the cold hard facts represented there and an attentive reader’s tolerance for ambiguities born of their juxtaposition with other corresponding cold hard facts, between what we read and what we fear or imagine, is a notable conflict capable of driving the story through a series of possible scenarios to the absence of an outcome. We are left bereft of an “ending” but in possession of all we need to know to occupy our minds for as long as it takes for us to complete the storyline.

To say it is a “neat template for alternative storytelling” is an understatement.

Below is story made out of facts using that Harper’s Index format about the “high costs” of treating pancreatic cancer. These figures show us how a factual storyline may move us from an empathetic take on cancer costs (Bud’s a nice guy; he has “beaten the odds” so far; it could happen to anyone, even me, yikes!) to a kind of dispassionate economic detachment caused by a consideration of the surprising and rising costs of said treatment (fiscal conservatives might characterize the total cost, as the authors of this report do, as “staggering”) - $2.6 billion annually and rising due to growth in the number of pancreatic cancers.

What this story does is build a case for a mean-spirited plot twist into an otherwise sympathetic narrative progression about what it costs to treat this deadly disease. The high costs of treatment and growing incidence of cancer interrupt (and for some readers, disable) the ability to resolve the original conflict by means other than reduced funding for terminal illnesses in their last stages and/or large cuts to federal and state programs, such as Medicaid, that step in when insurance runs out.

But we are talking about more than money. We are talking about the cost and value of offering support for human lives. We are describing the high cost of death, where this high cost is associated in the public sphere with “throwing money away” on cancers that have no cure. For those of us who put on our Chemosabe ballcaps and go to war fighting this disease every day, the absence of a known cure is not the point. How well we live, how long we live well – these are the questions.

So in the style of Harper’s Index I also provide an ironic last entry, one that reminds readers of how much money (to say nothing of how many lives) we spend fighting other “unwinnable wars.” And I leave the page knowing that while this narrative plot twist and resulting ending is not a resolution, it is, I hope, a useful way to think about our budget priorities.

Like this:

Number of men who will receive a pancreatic cancer diagnosis this year: 18,850

Number of women: 18,540

Number of individuals every day/year in the United States who will receive a pancreatic cancer diagnosis in 2012: 118/43,000+

Median survival rate for metastatic disease with treatment: 6-10 months

Without active treatment: 3–5 months

(Bud’s remarkable survival, so far: 14 months)

Duration of care and average cost in 2006 of pancreatic cancer treatment:

Mean time from diagnosis to death: 13.6 months

Mean duration of treatment 12.6 months.

During the period of treatment, mean monthly anti-cancer treatment and additional pharmacotherapy costs: $3,771 and $3,196 respectively.

Mean monthly cost of hospitalizations and clinic visits in 2006: $2,258 and $213.

In the last twelve months of life, the most expensive months: $65,557, $58,820, $47,727 respectively. -3, -5, and -2 (death = 0)

Breakdown of costs in the three most expensive months: anti-cancer agents (82%), hospitalization (15%), additional pharmacotherapy (3.0%), and clinic visits (0.5%).

2000-2012 mean costs of pancreatic cancer: $61,700/patient per year

Total bill when factoring in all indirect and additional costs of treatment: $2.6 billion annually in the U.S.

The official budget for the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq: $1.3 trillion

Estimated total costs to American taxpayers, includes the official Pentagon budget, veterans' medical and disability costs, homeland security expenses, war-related international aid and the Pentagon's projected expenditures to 2020: $3.7 – $4.4 trillion.

Figures such as these used to remind me of Joseph Stalin’s famous line: “a single death is a tragedy, a million deaths is a statistic.”

But then I became the veritable embodiment of both the single death and part of the ominous and un-erasable larger statistic. I am fighting an unwinnable war. But it’s a good fight.

***

Everyone in America walks by the gun on the table at least once a day.

The 1911 is a fine weapon.

Everyone in America tries not to think about the high cost of healthcare.

Maybe ObamaCare,

maybe belt-tightening austerity,

Or getting out of unfunded wars

and redirecting federal spending

to domestic needs …

Everyone in America walks by the same gun on the same table

at least once a day,

(The 1911 is a fine weapon)

And we try not to think about the high cost of healthcare.

***

Until we entered Cancerland San and I had little understanding of the high cost of chemo or radiation treatments or the rest of the cost associated with it. Our “co-pay” for prescribed drugs was limited to an occasional antibiotic or a preventative flu shot. We carried our health insurance cards in our wallets. Every year a shiny new card replaced the older one. We didn’t give it a thought. Not really.

Sandra and I are proud Americans who have worked hard all of our lives, paid our taxes, and contributed (in my case for over 40 years; San for over 30) to our own health insurance coverage. We’ve “played by the rules” and as a result we always assumed that healthcare, when we needed it, would be provided. With precious few glitches and a careful and persuasive team of advocates (thanks Terri!), that has proved true and it has been provided.

In this nether region of Cancerland we have purchased the rightly punched “tickets to ride,” but we have also seen friends and those who may have become friends save for their lack of insurance coverage, die. In every single case it has not been the denial of coverage that killed them – Four Winds and Chandler Regional Hospital and other healthcare providers kindly offer payment plans for every budget even when it impacts negatively their bottom line and we have witnessed compassionate small business owners step up for a valued workers – but the cancer non-survivor’s own decision not to further burden their families and their friends.

They chose death over debt, over shame (where there should be none), over a diminished life, over further assaults to the body and mind, and over a turn in the narrative about their own lives that robbed them of a good death, a good and true story that underscores the good person they tried to become. In the end they didn’t care very much, if at all, about the money. They cared about people. They cared about each other.

There is an existential lesson here. In the end you are not just a statistic. You are a loved one. A family member. A human being. What your family wants for you is what you want for yourself – a good life and, as much as it is ever possible, a good death. Better if it is painless, better if the end be quick. Better if there is that eternal white light down the tunnel at the end of the journey, if only to light the unknown passageway to another grand Cosmic adventure.

But a good death regardless, however you may define it.

***

The National Cancer Institute: “The incidence of suicide in cancer patients may be as much as 10 times higher than the rate of suicide in the general population.”

The Department of Defense: “The Army hit a grim milestone last year when the suicide rate exceeded that of the general population for the first time: 20.2 per 100,000 people in the military, compared with the civilian rate of 19.5 per 100,000. The Army's suicide rate was 12.7 per 100,000 in 2005, 15.3 in 2006 and 16.8 in 2007.”

Although I am not one to judge the decisions of others who fight a war “out there” (whether it be in the Room of Orange Chairs, or the hellhole of Iraq, Afghanistan, or other places around the world where our fine military is deployed), it is a fact that the war “out there” seldom ends when soldiers or cancer patients come home. There is also a “war within.”

Please do not misread this analogy. I am not saying that we should cut funding for veterans in order to better support cancer patients, or vice-versa. As a kid I grew up in a household where my beloved father suffered from PSTD long before it was named and the VA offered treatment programs. I know first-hand the importance of staying ahead of a downward-spiraling narrative that moves depression into despair. I know what it is like to stop someone you love from committing suicide by taking away car keys and liquor and pills.

But I also know that no one – and I do mean no one – can fully understand the pain of another person. From that lack of understanding – that lack of an “I get it” – the narrative turns from one that is all about hope, gratitude, and that symbolic light at the end of that tunnel to one that quietly moves into an unquiet silence.

That gun? That well-oiled and fully loaded state-of-the-craft 1911 is always there. I don’t fear it. I don’t plan to use it.

“Suicide is painless” (remember this refrain from M*A*S*H?) but it’s not for me. That so many others find it the right way out of here is not something I dwell on, but it is part of the general narrative concerning healthcare spending. And the rude fact that both cancer patients returning from the hospital or treatment centers and soldiers returning from war zones choose self-inflicted death over the waiting game at an alarmingly high rate should trouble us all.

Why? Because we lack a satisfying conclusion to both of these storylines. We lack what my military friends are calling “an exit narrative.”

***

Why is that?

Why is it that one of the only truths we can all agree on – that we all will one day die – still has a big narrative hole in it? What is a “good death?” Is there such a thing?

As members of diverse American tribes, each one holding different scientific, philosophical, and spiritual values and beliefs, until we can provide widely acceptable answers to those two questions, money spent on treatments designed to prolong life – or even to fund adventures in our “bucket lists” - are little more than narrative fragments - rhetorical placeholders - that, like the fine gun on the table, is little more than a reminder that we have unfinished narrative business. But do we have the will to do the work?

The hard economic questions about the “a good death” in relation to the high cost of treatment, end-of-life care, pharmaceuticals, and other associated costs of terminal cancer, is not a conversation we much engage in. I suspect the same may be true of you and your family. It’s not that we don’t care how much it costs or that we are disinterested in how our country will pay its bills; it is simply an unresolved dangling conversation about a moral dilemma that seems almost pointless except as an academic debate. Almost. But not quite. For we all will die. We all want a “good death.”

Another way to consider what a “good death” might mean is through the Lakota Holy Man Tasunka Witko’s real-life pronouncement (or Sioux Chief Crazy Horse rendering of it in the 1970 film adaptation of Thomas Berger’s novel, Little Big Man) that “today is a good day to die.” In the film the Chief climbed atop his funeral pyre surrounded by the things in this life he loved, prayed and sang and waited for death to arrive. But it did not arrive. Instead it rained. Hard. He finally gave up the wait and rejoined his tribe. And his death? Not at all what he intended! He was murdered in a saloon while a friend - the book/film’s anti-hero, Jack Crabb - held his arms.

Probably that is a metaphor. Probably. And an ironic one at that - “held his arms” is two pennyweight words away from “held me in his arms,” which is not a bad way to go. It’s a way I would gladly choose, albeit with San and Nic doing the holding.

Full disclosure: San doesn’t believe there is any such thing as a “good death.” I’m pretty sure Nic agrees with her. We have read enough to know that in all likelihood my ending will hurt and our job - well, their job - will be to lessen the pain by increasing whatever dosage of whatever narcotic works. My “exit narrative” will likely not be that sweet little bit of personal philosophy (Humphrey Bogart: “I should never have switched from Scotch to Martinis”) or irony (Oscar Wilde: “Either that wallpaper goes, or I do”) or even the hopeful words of Jesus as they were recorded by Luke (“Father, into thy hands I commend my spirit”).

I don’t have a “famous last words” speechlette ready to go. If I did it would be akin to Errol Flynn’s “I've had a hell of a lot of fun and I've enjoyed every minute of it” and Henry Ward Beecher’s “Now comes the mystery.”

***

When you are living with cancer you are also dying from it. You talk about the things that matter the most and unless you’ve devoted a lifetime to studying the economics of cancer care, or you are an oncologist trying to figure out how to continue delivering high quality care in the current turbulent business environment, chances are pretty good that this topic is not the one that “matters the most.”

Neither is the imaginary fact of a gun on the table, however fine the weapon. We may walk by it, but do we pick it up? If we pick it up, what then?

***

Narratives that begin in conflict must be resolved in action. Something must be done. It doesn’t matter if the story told is one derived from traditional literary forms and formats, or it is drawn instead from a writing experiment that asks you to use, say, The Harper’s Index format as our template.