Two Unwinnable Wars and the Lack of an “Exit Narrative”: Harper’s Index Unfolds the Costs, Chekhov’s Gun Remains on the Table, Which all Leads to Asking What is a “Good Death,” and, Thankfully, then We Get Some (Interrupted) Rock n Roll Music

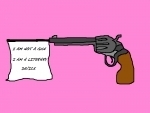

I place a Para Ordinance SSP 1911 pistol on the black coffee table.

It is a fine weapon and it is loaded.

When I teach my narrative writing seminars I begin with the Aristotelian or “classical” approach to structuring a good story and move through a history of literary innovations – structuralism, post-structuralism, postmodernism, and so on. My aim is to reveal to students the importance of craftsmanship to a well- told tale, where “craftsmanship” means how each part – the scenes, acts, characters and their attributes, and (if we are reading a masterwork) how every word spoken or silence retained, and of course the gun on the table contributes to the whole.

For those of you who do not dwell overly long in the narrative hot house of theorizing stories, the short version of why I might do something like that to otherwise very nice and intellectually curious students is pretty simple: How a story is told – its narrative structure/anti-structure – is a useful critical tool whether you plan to become a writer or a smart ass. It allows us not only to see into the intricate inner-workings of a story’s construction, but also to explain how a good story “works” (or doesn’t quite, or doesn’t at all) and why one story is or may be – using criteria drawn from the theory – better than another.

There is a useful analogy between the body and the story when teaching narrative structures. One of them is that a story’s structure is like a human skeleton: The bones are made to support the body (of the tale) and with some initial motivation to the nerve center in the brain and its release of the spine into action – there’s that need for a conflict to drive the action again – we find that the need to complete the narrative, to satisfy that conflict, becomes the vehicle that moves the skeleton/story forward.

Walter Fisher’s two criteria for evaluating a narrative extend the analogy between body and story: (1) it hangs together as a story, and (2) it rings true. The skeleton is what makes the story “hang together.” How well the story satisfies the initial conflict throughout the body of the tale, how artistically and pragmatically the narrative moves scene by scene through its trajectory to its ending, is how it “rings true."

***

That said, there are as many novel ways to meet the evaluative criteria for a good story as there are active imaginations. Some authors mimic older forms of storytelling, from the proud high-stepping prance of retold Homeric epic poems to the stylistic romantic elegance of greater and lesser forms of belles lettres.

Other writers do their own versions of a Geertzian “blurred genres” by combining two or more forms – say the scholarly fieldwork report and a class-based murder mystery with betting, blades, and fighting roosters set in Bali. Still others use what they know about the formal requirements for this or that literary form and/or style to “break the rules” of a genre and in so doing comment both on the fit of the subject as well on the genre itself.

***

The Harper’s Index format – a creative format for relaying facts against facts in a minimalist, ironic fashion – may also be used to “tell a story,” albeit in an unusual way. But between the cold hard facts represented there and an attentive reader’s tolerance for ambiguities born of their juxtaposition with other corresponding cold hard facts, between what we read and what we fear or imagine, is a notable conflict capable of driving the story through a series of possible scenarios to the absence of an outcome. We are left bereft of an “ending” but in possession of all we need to know to occupy our minds for as long as it takes for us to complete the storyline.

To say it is a “neat template for alternative storytelling” is an understatement.

Below is story made out of facts using that Harper’s Index format about the “high costs” of treating pancreatic cancer. These figures show us how a factual storyline may move us from an empathetic take on cancer costs (Bud’s a nice guy; he has “beaten the odds” so far; it could happen to anyone, even me, yikes!) to a kind of dispassionate economic detachment caused by a consideration of the surprising and rising costs of said treatment (fiscal conservatives might characterize the total cost, as the authors of this report do, as “staggering”) - $2.6 billion annually and rising due to growth in the number of pancreatic cancers.

What this story does is build a case for a mean-spirited plot twist into an otherwise sympathetic narrative progression about what it costs to treat this deadly disease. The high costs of treatment and growing incidence of cancer interrupt (and for some readers, disable) the ability to resolve the original conflict by means other than reduced funding for terminal illnesses in their last stages and/or large cuts to federal and state programs, such as Medicaid, that step in when insurance runs out.

But we are talking about more than money. We are talking about the cost and value of offering support for human lives. We are describing the high cost of death, where this high cost is associated in the public sphere with “throwing money away” on cancers that have no cure. For those of us who put on our Chemosabe ballcaps and go to war fighting this disease every day, the absence of a known cure is not the point. How well we live, how long we live well – these are the questions.

So in the style of Harper’s Index I also provide an ironic last entry, one that reminds readers of how much money (to say nothing of how many lives) we spend fighting other “unwinnable wars.” And I leave the page knowing that while this narrative plot twist and resulting ending is not a resolution, it is, I hope, a useful way to think about our budget priorities.

Like this:

Number of men who will receive a pancreatic cancer diagnosis this year: 18,850

Number of women: 18,540

Number of individuals every day/year in the United States who will receive a pancreatic cancer diagnosis in 2012: 118/43,000+

Median survival rate for metastatic disease with treatment: 6-10 months

Without active treatment: 3–5 months

(Bud’s remarkable survival, so far: 14 months)

Duration of care and average cost in 2006 of pancreatic cancer treatment:

Mean time from diagnosis to death: 13.6 months

Mean duration of treatment 12.6 months.

During the period of treatment, mean monthly anti-cancer treatment and additional pharmacotherapy costs: $3,771 and $3,196 respectively.

Mean monthly cost of hospitalizations and clinic visits in 2006: $2,258 and $213.

In the last twelve months of life, the most expensive months: $65,557, $58,820, $47,727 respectively. -3, -5, and -2 (death = 0)

Breakdown of costs in the three most expensive months: anti-cancer agents (82%), hospitalization (15%), additional pharmacotherapy (3.0%), and clinic visits (0.5%).

2000-2012 mean costs of pancreatic cancer: $61,700/patient per year

Total bill when factoring in all indirect and additional costs of treatment: $2.6 billion annually in the U.S.

The official budget for the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq: $1.3 trillion

Estimated total costs to American taxpayers, includes the official Pentagon budget, veterans' medical and disability costs, homeland security expenses, war-related international aid and the Pentagon's projected expenditures to 2020: $3.7 – $4.4 trillion.

Figures such as these used to remind me of Joseph Stalin’s famous line: “a single death is a tragedy, a million deaths is a statistic.”

But then I became the veritable embodiment of both the single death and part of the ominous and un-erasable larger statistic. I am fighting an unwinnable war. But it’s a good fight.

***

Everyone in America walks by the gun on the table at least once a day.

The 1911 is a fine weapon.

Everyone in America tries not to think about the high cost of healthcare.

Maybe ObamaCare,

maybe belt-tightening austerity,

Or getting out of unfunded wars

and redirecting federal spending

to domestic needs …

Everyone in America walks by the same gun on the same table

at least once a day,

(The 1911 is a fine weapon)

And we try not to think about the high cost of healthcare.

***

Until we entered Cancerland San and I had little understanding of the high cost of chemo or radiation treatments or the rest of the cost associated with it. Our “co-pay” for prescribed drugs was limited to an occasional antibiotic or a preventative flu shot. We carried our health insurance cards in our wallets. Every year a shiny new card replaced the older one. We didn’t give it a thought. Not really.

Sandra and I are proud Americans who have worked hard all of our lives, paid our taxes, and contributed (in my case for over 40 years; San for over 30) to our own health insurance coverage. We’ve “played by the rules” and as a result we always assumed that healthcare, when we needed it, would be provided. With precious few glitches and a careful and persuasive team of advocates (thanks Terri!), that has proved true and it has been provided.

In this nether region of Cancerland we have purchased the rightly punched “tickets to ride,” but we have also seen friends and those who may have become friends save for their lack of insurance coverage, die. In every single case it has not been the denial of coverage that killed them – Four Winds and Chandler Regional Hospital and other healthcare providers kindly offer payment plans for every budget even when it impacts negatively their bottom line and we have witnessed compassionate small business owners step up for a valued workers – but the cancer non-survivor’s own decision not to further burden their families and their friends.

They chose death over debt, over shame (where there should be none), over a diminished life, over further assaults to the body and mind, and over a turn in the narrative about their own lives that robbed them of a good death, a good and true story that underscores the good person they tried to become. In the end they didn’t care very much, if at all, about the money. They cared about people. They cared about each other.

There is an existential lesson here. In the end you are not just a statistic. You are a loved one. A family member. A human being. What your family wants for you is what you want for yourself – a good life and, as much as it is ever possible, a good death. Better if it is painless, better if the end be quick. Better if there is that eternal white light down the tunnel at the end of the journey, if only to light the unknown passageway to another grand Cosmic adventure.

But a good death regardless, however you may define it.

***

The National Cancer Institute: “The incidence of suicide in cancer patients may be as much as 10 times higher than the rate of suicide in the general population.”

The Department of Defense: “The Army hit a grim milestone last year when the suicide rate exceeded that of the general population for the first time: 20.2 per 100,000 people in the military, compared with the civilian rate of 19.5 per 100,000. The Army's suicide rate was 12.7 per 100,000 in 2005, 15.3 in 2006 and 16.8 in 2007.”

Although I am not one to judge the decisions of others who fight a war “out there” (whether it be in the Room of Orange Chairs, or the hellhole of Iraq, Afghanistan, or other places around the world where our fine military is deployed), it is a fact that the war “out there” seldom ends when soldiers or cancer patients come home. There is also a “war within.”

Please do not misread this analogy. I am not saying that we should cut funding for veterans in order to better support cancer patients, or vice-versa. As a kid I grew up in a household where my beloved father suffered from PSTD long before it was named and the VA offered treatment programs. I know first-hand the importance of staying ahead of a downward-spiraling narrative that moves depression into despair. I know what it is like to stop someone you love from committing suicide by taking away car keys and liquor and pills.

But I also know that no one – and I do mean no one – can fully understand the pain of another person. From that lack of understanding – that lack of an “I get it” – the narrative turns from one that is all about hope, gratitude, and that symbolic light at the end of that tunnel to one that quietly moves into an unquiet silence.

That gun? That well-oiled and fully loaded state-of-the-craft 1911 is always there. I don’t fear it. I don’t plan to use it.

“Suicide is painless” (remember this refrain from M*A*S*H?) but it’s not for me. That so many others find it the right way out of here is not something I dwell on, but it is part of the general narrative concerning healthcare spending. And the rude fact that both cancer patients returning from the hospital or treatment centers and soldiers returning from war zones choose self-inflicted death over the waiting game at an alarmingly high rate should trouble us all.

Why? Because we lack a satisfying conclusion to both of these storylines. We lack what my military friends are calling “an exit narrative.”

***

Why is that?

Why is it that one of the only truths we can all agree on – that we all will one day die – still has a big narrative hole in it? What is a “good death?” Is there such a thing?

As members of diverse American tribes, each one holding different scientific, philosophical, and spiritual values and beliefs, until we can provide widely acceptable answers to those two questions, money spent on treatments designed to prolong life – or even to fund adventures in our “bucket lists” - are little more than narrative fragments - rhetorical placeholders - that, like the fine gun on the table, is little more than a reminder that we have unfinished narrative business. But do we have the will to do the work?

The hard economic questions about the “a good death” in relation to the high cost of treatment, end-of-life care, pharmaceuticals, and other associated costs of terminal cancer, is not a conversation we much engage in. I suspect the same may be true of you and your family. It’s not that we don’t care how much it costs or that we are disinterested in how our country will pay its bills; it is simply an unresolved dangling conversation about a moral dilemma that seems almost pointless except as an academic debate. Almost. But not quite. For we all will die. We all want a “good death.”

Another way to consider what a “good death” might mean is through the Lakota Holy Man Tasunka Witko’s real-life pronouncement (or Sioux Chief Crazy Horse rendering of it in the 1970 film adaptation of Thomas Berger’s novel, Little Big Man) that “today is a good day to die.” In the film the Chief climbed atop his funeral pyre surrounded by the things in this life he loved, prayed and sang and waited for death to arrive. But it did not arrive. Instead it rained. Hard. He finally gave up the wait and rejoined his tribe. And his death? Not at all what he intended! He was murdered in a saloon while a friend - the book/film’s anti-hero, Jack Crabb - held his arms.

Probably that is a metaphor. Probably. And an ironic one at that - “held his arms” is two pennyweight words away from “held me in his arms,” which is not a bad way to go. It’s a way I would gladly choose, albeit with San and Nic doing the holding.

Full disclosure: San doesn’t believe there is any such thing as a “good death.” I’m pretty sure Nic agrees with her. We have read enough to know that in all likelihood my ending will hurt and our job - well, their job - will be to lessen the pain by increasing whatever dosage of whatever narcotic works. My “exit narrative” will likely not be that sweet little bit of personal philosophy (Humphrey Bogart: “I should never have switched from Scotch to Martinis”) or irony (Oscar Wilde: “Either that wallpaper goes, or I do”) or even the hopeful words of Jesus as they were recorded by Luke (“Father, into thy hands I commend my spirit”).

I don’t have a “famous last words” speechlette ready to go. If I did it would be akin to Errol Flynn’s “I've had a hell of a lot of fun and I've enjoyed every minute of it” and Henry Ward Beecher’s “Now comes the mystery.”

***

When you are living with cancer you are also dying from it. You talk about the things that matter the most and unless you’ve devoted a lifetime to studying the economics of cancer care, or you are an oncologist trying to figure out how to continue delivering high quality care in the current turbulent business environment, chances are pretty good that this topic is not the one that “matters the most.”

Neither is the imaginary fact of a gun on the table, however fine the weapon. We may walk by it, but do we pick it up? If we pick it up, what then?

***

Narratives that begin in conflict must be resolved in action. Something must be done. It doesn’t matter if the story told is one derived from traditional literary forms and formats, or it is drawn instead from a writing experiment that asks you to use, say, The Harper’s Index format as our template.

The moral of the cancer cost story regardless of your choice of actions is always the same one. You must choose treatment or a somewhat earlier death. We chose treatment and that has made a world of difference not just in terms of longevity and quality of life, but moreover in our ability to remain positive, to accept help, and to focus on small victories that are so much a part of our ability to deal with this damned disease.

But is this a selfish choice?

Given that I know I am doing to die and my death will be related one way or another to Stage IV Pancreatic Cancer, am I selfishly prolonging what is already end-of-life palliative treatment and care? And is my choice a morally correct one?

Is the fact that I have dutifully paid my taxes and healthcare insurance costs for over 40 years enough of a moral balance to justify the care I now receive?

How much, friends, is a human life worth? How much is my life worth?

***

There is a move underway under the austerity initiatives in Europe to stop government funding of Stage IV cancer treatments. This is unfortunate for many humane reasons, not the least of which is that Stage IV diagnoses are no longer simply death sentences nor is treatment of Stage IV illness a pointless and costly exercise with little, if any good to come out of it. Stage IV is a label used to describe an empirical set of facts, not a prescription for how best to live what remains of life or a prediction useful for calculating cost effectiveness or longevity.

I think I am living proof of that claim. I’ve done some of my best living and certainly some of my best writing under this “death sentence.” I don’t know what Court of Cancer Inquisitors I would have to face to prove my worth, what “death panel” I might have to face to justify what’s left of my life. But I’m pretty sure if I show up wearing a sharp suit and leaning on my cool bamboo cane their judgment would be like that of several judges I’ve heard when I show up for jury duty. “Sir, you look like you have better things to do than be here today. Dismissed.”

The larger news and the better data that ought to inform this very real debate is that we are clearly within reach of a day when treating many cancers will be much like treating other chronic illnesses. Yes, it is costly. Yes, treatment only prolongs the inevitable. Yes, we are all going to die. But life is sacred. Our life is sacred.

Or is it? More to the point: should that claim to the sacred be the defining argument? Is it really up to God how we should die? Is there a God? If there is a God, does S/he care what death awaits us?

Faith and prayers may well determine your answer and my own. But our answer – our faith in the goodness of that final transit – may be little more than another symbolic substitution of the sacred human life for the backstory of Stalin’s human tragedy or for an answer to the presence of Chekhov’s as yet unresolved pay-off – an untouched and fully loaded 1911 gun.

Or is it just this: Our vain attempt to prolong life by claiming the sacred is merely another way of showing our hubris? Should we instead just accept death with a Stoic secular face, forgo treatments with one trembling hand held high, and take that last fated breath, happy to know in our hearts that we haven’t further burdened a federally mandated healthcare system?

Go ahead. You first.

***

That gun? It’s still on the table.

***

That Harper’s Index template for telling this story of a moral dilemma? It’s still there, too.

***

I feel the build to a narrative climax gathering around the unknowns of my cancer, that gun, the index, and some music. Not just any music. Not just any index. Not just any gun.

Not just any cancer. It’s my cancer. And this is my cancer narrative, my unwinnable war, me and my loved ones fighting this good fight, and we know not where it ends, or how it ends, or why.

We don’t need to know. Not yet.

All shall be revealed in the fullness of time …

***

Last night in London Bruce Springsteen fulfilled what he called a 50-year old dream: Before a crowd of 65,000 people he sang “I Want to Hold Your Hand” and “Twist and Shout” with Sir Paul McCartney. Right up until 10:40 p.m., when the local council authorities shut off the power due to “curfew.”

Oh my. Talk about an “interrupted narrative!” The Boss said he had waited his whole life for this moment and no doubt Sir Paul was enjoying it too, to say nothing of the obvious delight of the large crowd.

They were singing, dancing, and having the time of their lives. Then the power to the stage was suddenly cut. Their music - loud and perfect just seconds before - died out, leaving the singers in mid-song and the band in mid-jam. The hot stage lights cooled as they faded into black.

And that was the end of that.

***

Sources:

Cancer costs: Journal of Clinical Oncology, 2006 CO Annual Meeting Proceedings Part I. Vol 24, No. 18S (June 20 Supplement), 2006: http://www.asco.org/ascov2/Meetings/Abstracts?&vmview=abst_detail_view&confID=40&abstractID=33928. This remains an underestimate as surgery, radiation, and indirect costs are not included. 2000-2011 costs from Costs and trends in pancreatic cancer treatment. O'Neill CB, Atoria CL, O'Reilly EM, Lafemina J, Henman MC, Elkin EB. Outcomes Research Group, Department of Epidemiology and Biostatistics, Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center, New York, New York. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22415469. Total costs including indirects, The Average Cost of Pancreas Cancer | eHow.com http://www.ehow.com/about_5549703_average-cost-pancreas-cancer.html#ixzz20eo9m45V.

Cost of Iraqi and Afghanistan wars: http://truth-out.org/news/item/8238-the-real-costs-of-war

National Cancer Institute on evaluation of cancer and suicide: http://www.cancer.gov/cancertopics/pdq/supportivecare/depression/Patient/page5

Military suicides/PTSD statistics: http://ptsdcombat.blogspot.com/2009/11/afghanistan-iraq-veteran-suicide-rate.html

Famous last quotes: http://www.corsinet.com/braincandy/dying.html

Springsteen and McCartney: http://edition.cnn.com/2012/07/14/showbiz/music/springsteen-mccartney-power-cut/index.html

H.L. Goodall Jr.'s Blog

- H.L. Goodall Jr.'s profile

- 3 followers