Laura Crossett's Blog

July 19, 2025

The Laura Index

NPR and PBS

National, international, and local independent journalism outfits

NPR and PBS via my local alternative monthly paper

Legal defense funds for illegally deported immigrants

Food pantries

Individual fundraisers for people suffering crippling medical bills (and the income they’ve lost to their illnesses)

Colleges and universities I attended

Arts organizations

Libraries

“In the Wisconsin Public Radio studio.” by Ann Althouse is licensed under CC BY-NC 2.0.Things to which I have not been asked to donate money (beyond the taxes and bills I already pay):

“In the Wisconsin Public Radio studio.” by Ann Althouse is licensed under CC BY-NC 2.0.Things to which I have not been asked to donate money (beyond the taxes and bills I already pay):Highway maintenance

Wastewater treatment

Garbage, recycling, and compost collection

Military and police equipment

ICE

Urban and rural electrification

Traffic cameras

AI powered surveillance systems in schools

Subsidies to big ag farmers and ranchers

“Mississippi Bridges from the top of the Arch” by ahisgett is licensed under CC BY 2.0.

“Mississippi Bridges from the top of the Arch” by ahisgett is licensed under CC BY 2.0.If you are not of the opinion that libraries, educational institutions, and affordable healthcare are public goods on par with safe highways and clean drinking water, nothing I say here is likely to convince you otherwise.

If you are frantically entering credit card information or PayPal passwords or sending checks to support the former category, well, yes, that’s probably about all we can do at the moment. Heck, I do it too.

Years ago Ira Glass used to do a lot of spots for Chicago Public Radio fund drive week in which he talked about how beautiful it was that public radio was the one medium completely funded by its listeners, and how wonderful it was that we could support this medium all on our own. It always made me want to scream. Yes, public broadcasting has come to rely more and more on private donations over the years. I think that is a bug, not a feature.

Public goods are meant to be paid for by us all and used by us all, whether they are solid bridges that don’t collapse, arts education in schools, public libraries, or healthcare that keeps everyone safe, healthy, and able to participate in the world.

Perhaps you think ICE is a public good. I disagree—but if you want to argue that it is, I hope you think long and hard about just what other services you’re willing to give up. Enjoy your sewer sludge.

Agree? Share! Disagree… well, that’s your choice.

NOT a photo of sewer sludge. “Manhattan Skyline and Newtown Creek Wastewater Treatment Plant at Magic Hour – NYC” by ChrisGoldNY is licensed under CC BY-NC 2.0.

NOT a photo of sewer sludge. “Manhattan Skyline and Newtown Creek Wastewater Treatment Plant at Magic Hour – NYC” by ChrisGoldNY is licensed under CC BY-NC 2.0.

July 9, 2025

This Is Where People Disappear

This is ICE office in Cedar Rapids, Iowa. It’s a 22 mile straight shot north of my house, the directions so simple I didn’t even bother with GPS. Exit 17 off I-380 takes you through a neighborhood of motels, fast food joints and gas stations to a street lined with warehouses, janitorial services, a landscaping business, some empty lots, and this nondescript brick building tucked back from the street next door to an Elks Lodge.

Protestors outside the ICE office in Cedar Rapids, Iowa. Across the street is a Goodyear Tire shop. Next door is an Elks Lodge.

Protestors outside the ICE office in Cedar Rapids, Iowa. Across the street is a Goodyear Tire shop. Next door is an Elks Lodge.There’s no sign from the road. On Google Maps it shows up as “Homeland Security Investigations.” On Apple Maps the building isn’t labeled at all. According to their website, this is the St. Paul Field Office, and it covers 32 counties in eastern Iowa, about a third of the state by area.

This morning a crowd organized by the Iowa City Catholic Worker and Escucha Mi Voz gathered there to protest the deportation of a young man named Pascual Pedro Pedro. Shortly before the crowd gathered this morning, a young man went in for his ICE checkin where, we were told, he was giving a choice: get arrested now or sign these papers swearing you will self-deport in the next 30 days. He chose the latter.

Last week Pascual showed up for his checkin but was not offered that choice. He was arrested and transferred first to the Muscatine jail, then to a detention facility in Louisana, and then deported back to Guatemala.

By now stories of ICE raids and deportations flood my inbox and my social media and the news every day, probably yours, too. Often they are dramatic—footage of ICE agents, dressed like common thugs, raiding workplaces or seizing people as they walk down the street. Often these actions take place in big cities, places far away from the supposedly all-white red state I occupy in flyover country.

But we aren’t all white in Iowa: like everywhere in the U.S., we are place built by immigrants, with each successive wave bringing new skills, new foods, new cultures, new contributions. You can get German and Czech food where I live but also Vietnamese. You can meet people from Sudan and Guatemala and China. Now our government wants to deport some of those people, and we do so in the most banal of all possible ways. A routine checkin at a nondescript government building with a paper sign taped to the window. A place you enter and may never exit the same.

According to ICE’s website, they have more that 400 offices around the country and the world—many of them I imagine, offices much like this one, although my admittedly cursory searches have failed to turn up much information. If you’d like to try to figure out where and how you might schedule a checkin appointment with your local ICE office via their website, I invite you to do so (particularly if you’ve never had the unique pleasure of navigating a government services website before).

People talk a lot about the banality of evil. I haven’t read Hannah Arendt, so I won’t do that, except to say that I wonder if this is part of what it means. A squat brown brick building, unmarked on some maps. A place you’d miss if you blinked on your way to your residence inn or to an electrical or plumbing supply warehouse, or perhaps to yoru job at the Area Education Agency. A place that says Homeland Security on a sign with a blank white circle, no seal. A hole in the world where you enter to face a fate you cannot know. A place where people disappear.

Reading makes nothing happen, but perhaps it spurs it.

June 9, 2025

Some Notes on The Great Gatsby

I have started Tillie Olsen’s Silences many times but never finished it. In fact, I started it again just now until I remembered that I was going to write something about The Great Gatsby, that I had, in fact, started writing it and then abandoned it, as with so much else. What follows is not so much the thing I was going to write about Gatsby as some notes toward it. I publish them in such a state because I shall never finish.

Me with my copy of Silences

Me with my copy of SilencesReader, be warned: I am about to talk at some length about The Great Gatsby. (If you have not yet had the opportunity to hit delete, by all means do so now.) I am, I should note, in no way qualified to speak about Fitzgerald’s book except insofar as I a human being with eyeballs who has read it on more than one occasion since the summer of 1996, when according to both the inscription in my copy and my memory, I first read it after picking it up at a used bookstore in San Francisco, where I lived between my sophomore and junior years of college. Does the length and slightly odd cadence of my sentence suggest to you that I have been reading it again? You would be correct.

Last week someone mentioned on the internet that they were planning to read it and what did people think, and if anyone liked it, why? Reviews were mixed, but after pummeling the original poster with the questions below, and then making several other observations, I realized perhaps I should stop taking up her space and start taking up mine. So here we are.

I did not read the book in high school, nor was it ever assigned to me. I am unclear on why anyone would assign it to a high school class, except, I suppose, that it is short—but in the year of our Lord 2025 with so many possible books to assign to high school students, a largely unrelatable one full of casual and not-so-casual racism (however accurate to the time) is not one I’d pick. But as noted, I was never required to read it—I picked it up at a used bookstore in San Francisco in 1996, probably because it was a Famous Book I thought I should read.

I thought it was okay. But in conversations with my two smartest college friends, and in rereading it over the years, I’ve come to see so much in it. Is that the same as loving it? Perhaps not—probably not—but it is, for me, a form of love.

So. My notes.

Substack yells at me if I don’t suggest you share this, but really, you don’t have to.

So much leads up to Gatsby, and so much comes from it. But to start with the lead up: if you’ve read the book, you know the ending:

And as I sat there brooding on the old, unknown world, I thought of Gatsby’s wonder when he first picked out the green light at the end of Daisy’s dock. He had come a long way to this blue lawn, and his dream must have seemed so close that he could hardly fail to grasp it. He did not know that it was already behind him, somewhere back in that vast obscurity beyond the city, where the dark fields of the republic rolled on under the night.

Gatsby believed in the green light, the orgiastic future that year by year recedes before us. It eluded us then, but that’s no matter?—tomorrow we will run faster, stretch out our arms further???… And one fine morning?—

That green light haunts Gatsby, it haunts the narrator (and a question for you—who is the protagonist of this novel?), it haunts the reader. And when, some years ago, I came across this, it began to haunt me a new:

It were a vain endeavour,

Though I should gaze for ever

On that green light that lingers in the west:

I may not hope from outward forms to win

The passion and the life, whose fountains are within.

That? That’s Samuel Taylor Coleridge, a poet Fitzgerald surely read and knew. Whether Gatsby’s green light, that orgiastic future, was directly remembered from Coleridge’s green light of passion and life we can’t know, but there it is—receding before us, yet we gaze, even in vain, toward that dream, never recognizing its true source.

And what about what came after Gatsby? So much—more than I can count, far more than I am qualified to say. There would be no J.D. Salinger without Gatsby, I thought as I read it again last week. And there would be no Kerouac. Look at the ending of Gatsby again (I’ll wait) and then read this most beautiful (to me) of sentences in all of American literature:

So in America when the sun goes down and I sit on the old broken-down river pier watching the long, long skies over New Jersey and sense all that raw land that rolls in one unbelievable huge bulge over to the West Coast, and all that road going, and all the people dreaming in the immensity of it, and in Iowa I know by now the children must be crying in the land where they let the children cry, and tonight the stars’ll be out, and don’t you know that God is Pooh Bear? the evening star must be drooping and shedding her sparkler dims on the prairie, which is just before the coming of complete night that blesses the earth, darkens all the rivers, cups the peaks and folds the final shore in, and nobody, nobody knows what’s going to happen to anybody besides the forlorn rags of growing old, I think of Dean Moriarty, I even think of Old Dean Moriarty the father we never found, I think of Dean Moriarty.

There they are, the dark fields of the republic rolling on under the night, on toward some distant, illusive, barely graspable future.

Me with my copy of The Crack Up, which Tillie Olsen wrote about and which I did read once, long long ago

Me with my copy of The Crack Up, which Tillie Olsen wrote about and which I did read once, long long agoI should note before we go that Gatsby is often very, very funny. Take this scene at a party at Gatsby’s house, where Jordan Baker and Nick Carraway have just entered Gatsby’s “high Gothic library”:

“What do you think?” he demanded impetuously.

“About what?”

He waved his hand toward the bookshelves.

“About that. As a matter of fact you needn’t bother to ascertain. I ascertained. They’re real.”

“The books?”

He nodded.

“Absolutely real?—have pages and everything. I thought they’d be a nice durable cardboard. Matter of fact, they’re absolutely real. Pages and?—Here! Lemme show you.”

…

“See!” he cried triumphantly. “It’s a bona-fide piece of printed matter. It fooled me. This fella’s a regular Belasco. It’s a triumph. What thoroughness! What realism! Knew when to stop, too?—didn’t cut the pages. But what do you want? What do you expect?”

Every book its reader; every reader their book, said the late great S.R. Ranganathan. This one may not be for you. But trhere’s something about the mixture of misplaced romantic longing, misplaced ambition, and misplaced admiration in Gatsby that gets me every time, and while it tends toward the overly descriptive, there are few scenes in literature as vivid in my mind as that of the mint juleps in the sweltering awful heat of a New York City hotel so long ago.

March 22, 2025

How long can that banner still wave?

They say that patriotism is the last refuge

To which a scoundrel clings

—Bob Dylan

If you know me (and let’s face it, if you’re reading this, you probably do), you know I am a huge fan of Bob Dylan and not at all a fan of the United States of America. And yet yesterday I had a sudden and intense urge to hang an American flag.

Wait, what? you say. Well, don’t worry—I didn’t hang a flag outside, in part because it was raining here, and you don’t hang a flag in the rain.1 (Also: You shine a light on it if you fly it at night. You fold it properly. You don’t let it touch the ground. And you don’t print it on a paper napkin that you use to wipe your mouth and then throw away.) But you see on Thursday I read this statement from Keith Sonderling, who was sworn in that day as director of the Institute of Museum and Library Services—sworn in in the building’s lobby, “accompanied by a team of security and staff from the Department of Government Efficiency, the federal advisory agency led by billionaire Elon Musk.” He then issued a statement:

I am committed to steering this organization in lockstep with this Administration to enhance efficiency and foster innovation. We will revitalize IMLS and restore focus on patriotism, ensuring we preserve our country’s core values, promote American exceptionalism and cultivate love of country in future generations.

—acting IMLS director Keith Sonderling

You know what unpatriotic things the IMLS funds? Well, let me tell you just a few.

Summer reading programs for children.

Internet access for libraries in poor and rural areas.

Scholarships for library school students.

Books for the blind and visually impaired.

And, of course, the workforce development and training that Republicans love to tout as the solution to getting everyone off the government dime.

Is there anything, I ask you, more Norman Rockwell than a children’s summer reading program at your public library? Is there an expression of patriotism more profound—aside, perhaps, from the Marines raising the flag at Iwo Jima2—than this collage of children from summer reading programs around the country that I picked from a simple Google search?3

The IMLS has been referred to as “obscure” by some news outlets, and indeed, it is, in the great scheme of the federal government, a tiny agency, with under a hundred employees and a budget of $294 million in FY2024—$266.7 million of which was given away in grants to libraries, museums, and archives. According to figures from the American Alliance of Museums, the IMLS accounts for a whopping 0.0046% of the federal budget.4

And yet what they do with that! Maybe you know this, but on average the public library ROI for any given community is about $4 in good to the town for every $1 invested in the library.5 Oh, I don’t need to tell you people what libraries mean and what they do. You know that, because you know me, and you read, and you care.

The IMLS is not by far the biggest victim of the Trump administration’s war on American democracy, and it won’t be the last. (The Department of Education was raided the same day, leading IMLS workers on Reddit to despair that the press was all there.) But the idea that they are defunding libraries to “restore the focus on patriotism” is what guts me.

I believe this country was founded by bigots and hypocrites. The “great compromise” I was taught to revere in school was dependent on the idea that some human beings were less than others—2/5 less, to be exact. I grew up after Vietnam, after Watergate, during Reagan. It was a hard time to believe in America.

In the days after 9/11 there were articles about 1960s radicals who were now flying American flags—the same ones who’d once listened to the Phil Ochs song I was playing on repeat at the time:

So do your duty, boys, and join with pride

Serve your country in her suicide

Find the flags so you can wave goodbye

But just before the end even treason might be worth a try

This country is to young to die

—Phil Ochs, “The War is Over”

In 1969, during that particular war, my father spent a few days holding a vigil beneath the American flag at Grinnell College to keep students protesting the Vietnam War from turning it upside down again. I’ve written about that quite extensively (and a few of you reading this were there). My mother told me the story when I was fifteen years old and on my way to a protest against the “first” Gulf War.

“Wow. If I’d been there,” I said, “I probably would have been one of the people trying to turn the flag upside down.”

“You and your father would have disagreed about a lot of things,” she said. “Call me if you need to be bailed out.”

My father, like many men of his generation, tried to serve in World War II. He did not make it through boot camp, but when he died, my mother, as his widow, was offered a headstone, burial in a national cemetery and, I believe, $100. She took the headstone and the money, and at his burial the oldest veteran in Enosburg Falls, Vermont recited “In Flanders Fields,” and my mother was presented with an American flag. It sits, properly folded, in her room to this day. I don’t know if we’ve ever flown it.

I’ve never thought of myself as a patriot, and I decry much of what this country was founded on and what it has perpetuated. But I will be damned if I let them take from me—from all of us—the things that we have, despite all of that, achieved.

I’ve never thought of myself as a patriot, and I decry much of what this country was founded on and what it has perpetuated. But I will be damned if I let them take from me—from all of us—the things that we have, despite all of that, achieved. The Bill of Rights. The 14th Amendment. The 19th Amendment. The Civil Rights Act of 1964. The Voting Rights Act of 1965. The Environmental Protection Agency. The Americans with Disabilities Act. The National Labor Relations Act. The Individuals with Disabilities in Education Act. Brown v. Board of Education. Gideon v. Wainwright—and, perhaps more importantly, the many, many people’s movements that made so many of those things possible, because power, as we know, concedes nothing without a demand, and we are all stronger together.

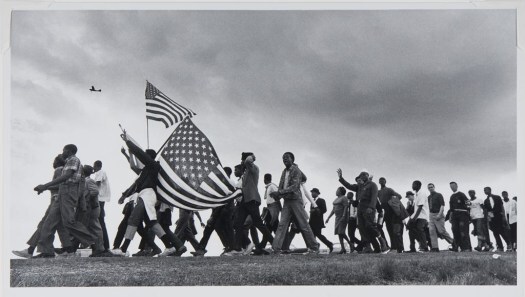

The March from Selma to Montgomery, 1965. Photo by Matt Herron.

The March from Selma to Montgomery, 1965. Photo by Matt Herron.I did not think that the demise of American democracy would hit me so hard. I did not think I had a patriotic bone—or even a nerve—in my body. But I was wrong. I wrote most of this last night. This morning I woke up thinking of the images of the flag that perhaps best represent what I’m trying to get at: those carried by marchers in the Civil Rights Movement. Accordingly I’m going to give James Baldwin the final word here, with all the hope I have left.

For this is your home, my friend, do not be driven from it; great men have done great things here, and will again, and we can make America what America must become.

—James Baldwin, The Fire Next Time

You’re welcome to share this, if the world really needs more pixels right now. Keep the light shining.

1There is, I have just learned, an exception for an all-weather flag. But my general point stands. I often want ask questions of the residents of a house I pass on occasion that has two American flags—one emblazoned with the text of the 2nd Amendment; the other with the Statue of Liberty and the caption “If you don’t like it here, I’ll help you pack.” I’m unclear on whether and how these meet the letter of the law.

2Oh wait, I forgot—they tried to remove that, too.

3Credits, clockwise: Lights! Camera! Read! at the Cincinnati & Hamilton County Public Library; Reading is a Thrill from the Oak Park Public Library; a summer reading presentation on water safety from the Drowning Prevention Coalition of Palm Beach County; 2023 Dr. Seuss Summer Reading Program in Galveston County, Maryland; and the 2013 Library Summer Reading Program at the U.S. Army Garrison Humphreys, South Korea. (I don’t have certain information that U.S. Army garrisons receive IMLS grants, but they definitely depend on public funding.)

4For the best coverage I’ve found, see this excellent overview from USA Today. Yes, really, USA Today.

5Here’s one extensive presentation from Texas. Search for “library ROI calculator” and you can probably find one near you.

November 6, 2024

When in Danger or in Doubt

For many years, I worked in public libraries, and among my duties I gave a report to the library board every year about my job and what I did. In 2018, in lieu of enumerating my duties in a resume-like fashion, I wrote the following and read it to them. I was reminded of it today and wanted to share it. Mourn, then organize—and maybe go for a walk to the library—and thank everyone who works there.

“Refuge” by Mark Lindner is licensed CC BY-NC-SA

“Refuge” by Mark Lindner is licensed CC BY-NC-SA“The years I spent getting high and reading library books I do not regret” is a line from The Mars Room by Rachel Kushner, a novel about a woman in California serving two consecutive life sentences and her reflections on her life both before and after she went to prison.

I posted this line on Facebook the other day and people got concerned that I was endorsing drug use, which I’m not. But I am saying that so much of the influence the library has on people we’ll never know. Part of my job is to help make it possible for us to have that influence, by doing mundane things such as keeping the desks staffed and ordering books to fill the shelves and weeding books to make room for the new ones.

Here, for instance, is the summer desk schedule. At any time, we need five people staffing the desks at the library, and because it’s summer, we often need extra coverage on some of the public service desks. In addition to our thirteen permanent, mostly full time staff, we have eighteen part time staff working here this summer (and we may be hiring another person). Those eighteen or nineteen people often have other jobs or classes or childcare obligations, and some days they get sick or take well-deserved vacations, so I spend a lot of time figuring out how we’ll cover the desks for both short and long term contingencies. This morning one of our part time staff texted E and me to say his daughter was sick and he could work his morning shift but would need the afternoon off so his wife could go to work, so I spent some time coming up with various solutions to that.

Of course, sometimes we do get to know something about the effect we have on our patrons’ lives. In addition to the work I do inside the library, I do some outreach. Today I went out with the Antelope Lending Library bookmobile for a stop at Western Hills. We’ll be there every Wednesday this summer. I told a woman who can’t drive anymore that we could deliver books to her on the bookmobile, and I signed up three kids for the summer reading program. “You get a tshirt at the end,” I said, trying to sound enthusiastic about something I can’t imagine being that exciting. “Oh!” said one girl. “My friend got one of those once!” They were thrilled at the prospect.

Every other week I also go out to the IMCC. We provide library books for the inmates there who’ve achieved the highest privilege level at the prison. I always wish we could serve all the patrons there, and I always wish I could carry more books. As with the regular library, most people there come, get their books, and go on their way. But one day there a patron said to me, “I heard that George Orwell wrote some other books besides Animal Farm and 1984.”

“He sure did!” I said, “and I can bring you some.” It turned out we didn’t have any editions of his essays, so I had K order one, and I took it out to him. I gave him a list of the ones you absolutely have to read—“Such, Such Were the Joys” and “Shooting an Elephant” and “Politics and the English Language”—and the next time I was out there he asked if he could keep the book for longer because he wanted to read some more.

Of course, sometimes the patrons we get to know aren’t so delightful. I spend a certain amount of time listening to a woman who calls the library frequently very worried about something she’s searched for and whether it will lead her to child pornography and whether that will get her in trouble. “Can you just look that up for me and see what it says?” she’ll say. As you can imagine, these aren’t fun conversations to have on the public service desk. “No, searching for kiddie po doesn’t bring up anything bad. I don’t really want to Google kiddie xxx for you.” I started having staff transfer all her calls to me to spare them from having to try to handle her questions gracefully and discreetly while working at a public desk. Now she calls the library and asks for me. Today she called three times, and the third time I asked her how recently she’d seen her doctor or her therapist (a few years ago she called and asked if I’d talk to her doctor on the phone—she was at her office). “I just got out of the hospital,” she said. I asked if that had helped, and she said a bit, and I asked about whether they’d scheduled a follow-up appointment and encouraged her to tell the doctor there all the things she’d told me today.

I started by quoting a new book and I’m going to end by quoting a much older one. Denis Johnson’s Jesus’ Son is a classic book about heroin addiction (or about the effects of urban renewal on Iowa City), but it ends with the narrator sober and working at a residential home for people with disabilities. He says, “All these weirdos, and me getting a little better every day right in the midst of them. I had never known, never even imagined for a heartbeat, that there might be a place for people like us.”

If the public library is anything, I hope it is a home for those people—and my job, as I see it, is to do what I can to keep the place running.

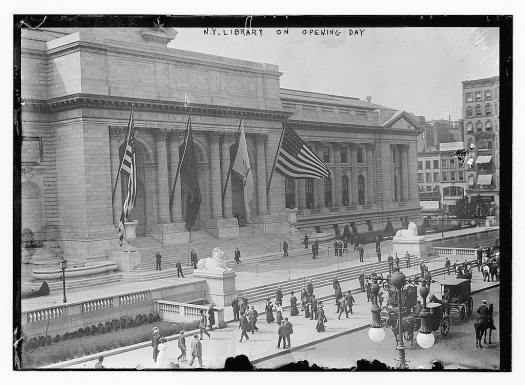

New York Public Library, with Patience and Fortitude. Public Domain.

New York Public Library, with Patience and Fortitude. Public Domain. I don’t work in a public library anymore, which, according to my kid, means I’m not a librarian anymore, and although I do work for libraries, I often agree with him. But my heart today—and every day—is with the people checking your books out and back in, helping people figure out online job applications while helping someone else scan a photo and upload it to Facebook for their family and explaining, for the twentieth time in twenty minutes, how the print release system works.

Your local public library is just that: local. Only a sliver of its funding and its control come from the state and federal government, and while the outcome of this election will empower the people trying to take over local library boards, it can’t give them away without a fight. That’s a fight you can be a part of. Please do.

If anything is bringing you some hope today (even this post), please share it.

August 14, 2024

Love Your Sofa

I woke this morning to ’s excellent piece on single mothers and to a Facebook memory of the final day of this little project I did back in 2016, which I’ve edited lightly and reproduced below.

#loveyoursofa Day 7.

A week or so ago I started seeing people posting pictures of their husbands (and it was always husbands) with a “love your spouse” tag and a note that this was part of a challenge to “promote marriage.” While it’s best, in general, not to take Facebook challenges and internet memes too seriously, this one set my teeth a little on edge.

Even a few years ago, many couples would not have been able to “promote marriage” in their posts because they were, in the United States, not legally allowed to marry. While the Supreme Court’s decision in Obgerfell v. Hodges happily overturned that state of affairs, it did so, in its majority opinion, in part by throwing other kinds of families under the bus: “Without the recognition, stability, and predictability marriage offers, children suffer the stigma of knowing their families are somehow lesser. They also suffer the significant material costs of being raised by unmarried parents, relegated to a more difficult and uncertain family life.”

Most families in the US today do not consist of heterosexual married couples on their first marriage.1

This was one of my most shared posts on Facebook. Feel free to share this version, too!

You may recall the Faith Based Initiatives of the first term of George W. Bush’s administration. One of their projects was to “promote marriage,” because, they believed, marriage was the cure to poverty. Katherine Boo wrote a devastating and brilliant article on how that played out for a couple of women in Oklahoma City.

We all know—usually from our own lives—that we do not represent our entire selves on Facebook. People who are the victims of domestic violence may represent even less–they may even falsify their lives for public consumption. Domestic violence was not illegal in most places until the 1970s. The national domestic violence hotline only went live in 1996. While I believe that most of the “love your spouse” posts I’ve seen come from people in genuinely loving and happy relationships, I don’t want to overlook the possibility that such memes feed into an abuser’s supply.

These are some of the sofas of my past. There’s my grandmother and our old cat Max on the sofa I grew up with, a thrifted orange monstrosity that my grandmother insisted my parents buy. It was ugly, but I was very fond of it. When I lived in Wyoming, I got the sofa on that ended up the cover of my book, and there I am with my baby and our cat after we got home from the hospital. A few years back I bought a brand new sofa for the first time—and then I got my dear sweet dog and of course ended up letting her lounge on it.

I’ve spent a lot of time with the sofas of my life—more than I have with any romantic partner—and they’ve gotten me through good times and bad, as have my wonderful, loving, and unconventional family.

I wish the same support for all of you.

1That’s a story from 2013, so the numbers may have shifted.

July 28, 2024

Are You a Mother?

I was raised in the church of primary texts and with the liturgy of close reading. The former we’ll get into some other time, but the latter often stops me dead. Consider, for instance, this line from “The Morning” newsletter of the paper of record, discussing the importance of Kamala Harris’s VP choice:

“She will be picking a partner who would help her govern.”

Okay. Fine, whatever. But stop. Let’s do a little though exercise and swap in some other names in place of that “she.”

Bill Clinton will be picking a partner who would help him govern.

Richard Nixon will be picking a partner who would help him govern.

Ronald Reagan will be picking a partner who would help him govern.

It lands a little differently, does it not? (I almost used George W. Bush, but arguably he did in fact just that, much to the detriment of all, particularly the people of Afghanistan and Iraq.)

Let’s try another:

Hillary Clinton will be picking a partner who would help her govern.

Yeah, I can see that in print. You get the point.

A stone cold classic.

A stone cold classic.The other day I was walking my dog in my neighborhood and saw a woman with a baby in a stroller also out for a walk. Years ago I was that woman—I would not have left my house for a walk without my baby, because my baby and I were the only people in the house. If I was out in the world without my baby, it was because I was paying someone or someone was doing me a favor, and if I saw people I knew when I was out in such a state, their first question was usually “Where’s X?” (where X = my offspring). But often they didn’t have to ask because my baby was with me. I was, wherever I went, a mother.

That doesn’t happen any more. My kid is old enough that people I know don’t expect him to be with me at all times. I am old enough that I have begun to acquire the invisibility cloak of age. People might assume I am a mother, but that would require that I register enough for them to pursue a line of thought about me that far.

What you see, of course, is a function of who you are. That is true nowhere more than online, where algorithms tailor content to your taste, and the more you engage, the more you teach the algorithm what you like. We call it “living in a bubble,” but that’s a poor metaphor for life online. We live, instead, at the end of a series of highly selective filters, as if we pulled only the fibers we liked from an enormous shop and then wove a tapestry from them, one with the pictures we most liked to see.

My filters, for instance, bring me the New York Times and a lot of people who like to argue with the Times, and thus I spend some time every morning reading their newsletter and then ranting about the picture they paint of the world. I do not know precisely how other people spend their time while drinking their coffee in the morning, though I am dimly aware that not everyone drinks coffee.

This morning my no-longer-a-baby asked me why Hestia was such an important goddess when she was in charge of such boring things.

Let that sink in for a moment.

In fact, I always thought she was kind of boring, too. Who wants to guard the hearth when other people are out there turning people into spiders or cavorting about with various animals or even getting taken to the underworld?

I pointed out that she was in charge of a lot of things we don’t regard very highly in the world but that most people still want (it is nice, at times, to come home to a cozy house and a hot meal, even if you’re an adventurer). It is possible probable I lectured a bit.

I draw no conclusions here, except that I am very tired of all the arguments I could make about everything I have said.

I have no clever caption for this button, but feel free to share.

In other news, I’m writing an adorable new newsletter for my job, and the first issue is free. If you want some links and some jokes about libraries, tech, and copyright, you should check it out.

CATS from Library Futures

CATS from Library Futures

April 20, 2024

How to Protest

Twenty-four years ago this month I was arrested, along with four other students, at a sit-in at Jessup Hall, the administration building of the University of Iowa.1 It was eleven o’clock at night—shift change, we learned a bit later—and the UI police entered the building in force, told us we had to leave, and then (if memory serves), chained the doors shut to prevent us from doing so until they’d had their say. One of our number escaped and managed to alert the press; the rest of us waited. Some chose to leave when told again. Some of us stayed and got arrested.

I can’t speak for my comrades, but I’ve always felt we stayed in part because getting arrested is part of protesting, in part because it seemed pretty rich that the university had only suddenly—at 11 p.m.!—become concerned about our health and safety (there was a lot of “fire hazard” and “ingress and egress” in what the cops said) after we’d been there six days, and in part because, as a wise young person recently told me, the point of a protest is to build community. We’d built a community in Jessup Hall in those six days—and in the many months that led up to them—and I for one wasn’t about to abandon it because some guy in a polyester uniform with a badge told me it was time to go.

We were handcuffed and booked, charged with trespassing, and barred from entering the administration building without permission from the dean of students for a year. (One of my fellow arestees remembers that we were also given three years’ probation.)

You will note that, despite camping in the hallway of the administration building—president’s office on one end; provost’s on the other; general counsel in the middle—for almost a week, holding teachins for more than a thousand students during that time, getting food delivered, playing guitar, hijacking a phone line in the basement, and generally making a stinky nuisance of ourselves, we were not suspended. We were not given fifteen minutes to collect our belongings from our dorm rooms. We were removed, but we were not expelled. We remained—and remain—unmoved in our convictions.

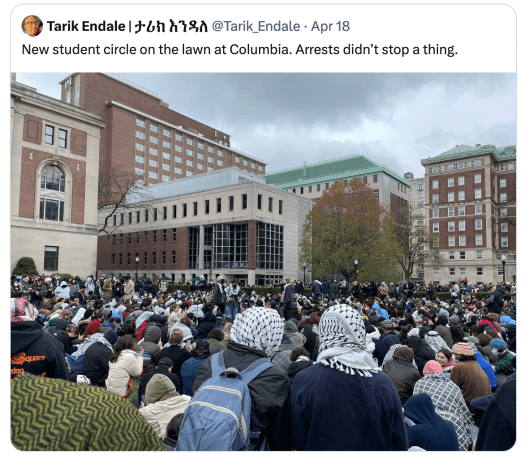

Moved but unmoved

Moved but unmovedI have watched the news from Columbia (and Barnard) the past few days with anger, sadness, and rage, and with utmost solidarity and respect for the student protesters there. Many of them have been suspended, but they remain unmoved—and their comrades remain, and return. My heart goes out to them, and to the people in Gaza whose existence they are fighting for.

Contempt is not an admirable emotion. But not all actions are admirable. University administrators have choices. The ones they have made with regard to student protesters leave me with little but contempt—contempt for their decision to call in police, contempt for their silencing of student voices, contempt for their disregard for the rights of students to hold opinions while getting an education, and utter contempt for their statements about the “proud history of protest” at their institutions.

Yes, I imagine the University of Michigan is proud to claim itself as the birthplace of Students for a Democratic Society, but how did they feel at the time? And when Mayor Eric Adams refers to the proud history of protest at Columbia, is he referring to the protestors or to the cops who beat students there in 1968?

I do not envy university administrators in any era. I also hold them to a very high standard. If you want to be an ivory tower, or a beacon, or a city on a hill, or just an institution doing its level best to prepare young peeople to be active participants in a democratic society; if you espouse humanitarian principles in your mission; if you talk about knowledge and truth; if you hold yourself up as an example of what the world should be, well, then, you have an obligation to try to live up to all that.2 It behooves you to behave as if you are in fact the head of a community that holds such ideals. And you don’t get to take pride in protesters of the past while surpressing protesters in the present.

Or at least you shouldn’t.

If you’ve ever been interviewed at a protest, you’ve probably been asked “What do you hope to accomplish here?”, and if you’re smart you’ll have a little soundbyte formulated for just that moment, and if you’re lucky the journalist will go off and write their story and your soundbyte will come through in a snappy and intelligent way. And maybe if you’re very lucky your protest will change something. People sometimes ask me if our protest did, and I used to say yeah, there’s one independent union at one factory in Mexico as a result.

But the protest also changed us, or at least it changed me. That movement—and every movement I’ve been involved in—gave me who I am. I’m still in touch with many of the people from that time, and I’m looking forward to gathering with them again in a year on the 25th anniversary of our sit-in and to hearing from current student activists about the things they are trying to change. Solidarity is important. Solidarity is real. A busload of striking steelworkers came to visit us on one day of our sit-in—piled into a bus (and a bunch of cars, because the bus ran out of room), drove two hours, went to our rally, and drove back home. I get shivers every time I think of them pouring out of that bus. We piled into cars of our own to attend a rally of theirs later that summer, because that’s what you do for the people who show up for you: you show up for them.

I send my solidarity out to Columbia and Barnard tonight, and to protesters everywhere, always.

Other newsSpeaking of protest, I have a profile of the high school student as a young activist out in Truthout today (or, as they put it, a profile of “the Teenager Challenging Iowa’s Anti-LGBTQ Legislation”—there’s a reason we writers don’t write our own headlines).

And speaking of Columbia, in January 2002 I was able to travel there to visit the library and special collections thanks to a UI Student Government Research Grant. I was there to read things from my father’s time at Columbia in the 1940s, but I couldn’t resist picking up the roll of microfilm from April 1968 (which was labeled something like “1968 Special”) and perusing it. These days you can do cool stuff like that online, I’m teaching a class on research for writers where you’ll learn more than you ever wanted to know about how to find cool stuff to inform and inspire your writing. If you’re interested but $200 is more than you can afford, let me know and we’ll work something out.

1In the interests of timeliness, the account of the sit-in here is based exclusively on how I remember things as I write them tonight. I wrote about the events at the time (see the 25th anniversary link for more), and they received a fair amount of press back then, but I have not fact checked my current recollections against them, and others who were there may, of course, recall things differently. We can discuss all that another time.

2From the Columbia mission statement: “The University recognizes the importance of its location in New York City and seeks to link its research and teaching to the vast resources of a great metropolis…. It expects all areas of the University to advance knowledge and learning at the highest level and to convey the products of its efforts to the world.”

Among the many missions, visions, and core values the University of Iowa touts, it “provides exceptional teaching and transformative educational experiences that prepare students for success and fulfillment in an increasingly diverse and global environment.”

My undergraduate college, I just learned, seeks to “inspire each individual to lead a purposeful life.” You get the idea.

April 16, 2024

How to Promote Your Own Work

Occasionally I am reminded—or I remember—that I should promote my own work and not just that of other people. (Although if you are in the Iowa City area, you should get your broken stuff fixed, free, on April 21! And if you’re looking for something good to read on the internet, I highly recommend shelling out a tiny amount of money every month to Flaming Hydra.)

I kind of miss that look for Firefox. My old cat Tyger circa 2007 with a 2003 iBook.

I kind of miss that look for Firefox. My old cat Tyger circa 2007 with a 2003 iBook.I fail to promote my own work due not to modesty (my ideas are great!) but largely because I have too many ideas (and thus as I sit down to write to you right now I’m also thinking about whether a bias binding or a bias facing is the way I want to go on a dress I’m making, some multi-media intern projects I heard about yesterday, storytelling, whether HR trainings can be gamified, whether gamification is a word that should exist, if I should try to put together a writing and research class for people who want to do jobs like mine, as was suggested to me recently, and, well, you get the idea). My brain is what it is. Sometimes it’s great; sometimes it’s out of tune.

Without wasting any more of your time, you can now find more Laura

writing for Truthout (my first piece, about banned books and ebooks, came out last month; my next, a portrait of the high school student as a young activist, will follow eventually)

teaching a class on research for writers (in person and on the internet!) via Porchlight in May

This newsletter has never had any design or import, but it did occur to me in titling this entry that “HOWTO” has been a theme (how to run a meeting! how to go to NYC!). If I were better at promoting myself, I’d keep that up. As it is, well, stay tuned. Or not.

March 22, 2024

The Girl from Western Civ

I come from Western civ. I say this neither as a good thing nor a bad one, not to brag or apologize (though I often begin every sentence with an apology)—I say it because it is where I come from and who I am, at the core, no matter what else I have encountered or learned. When I am feeling grandiose I think of myself as a sort of ivory tower, immutable. Winds and time and sometimes protests have altered the façade at Butler Library at Columbia University, but it still reads HOMER HERODOTUS SOPHOCLES PLATO ARISTOTLE and on and on, writers whose work has at one time been required reading for all Columbia undergraduates. When I stand in the center of campus and face that building, as I do every time I’m in New York, I feel not excluded, as I think I’m meant to: I feel at home. I am from Western civ in the way that people are from coal mines in Appalachia, or from the Mormon church, or who grew up in communes of off-the-grid hippies. “You can’t escape the influence a childhood specifically designed to influence you,” Chelsea Cain once wrote, and while her parents made what were, at the time, far stranger choices than those mine did, I feel a kinship with those words.

“Butler Library, Columbia University, Manhattan, New York, New York, United States” by Billy Wilson Photography is licensed under CC BY-NC 2.0.

“Butler Library, Columbia University, Manhattan, New York, New York, United States” by Billy Wilson Photography is licensed under CC BY-NC 2.0.My father was professor of Classics and humanities at a series of small liberal arts colleges; he held a PhD from Harvard and a BA from Columbia. He died in 1981, when I was five, but his books still fill my shelves. My profile picture here is me peeking out from behind a copy of his dissertation he was revising. Last year, on what would have been his 100th birthday, forty of his former students and colleagues gathered for three hours on Zoom to reminisce and pay tribute to their teacher and friend.

After college my mother applied to secretarial school and to PhD programs—she ended up in the latter, where she specialized in the period of English literature from Shakespeare to the death of Samuel Johnson. She went on to medical school, but we got to know some of our best family friends because one day during her urology rotation, the professor took all the med students for coffee in the cafeteria. He and my mom somehow floated into a conversation about Dante, leaving the other students scrambling. (“Dante? Dante who? Is this going to be on the test???“)

I read ’s newsletter (and you should, too!) and he’s gotten me thinking about this business of who I am and where I come from. Like many white people I know, I want to be the right kind of white. I want to rush in and comment that when I hear news about heinous crimes, I always hope it’s a white dude who committed them, which seems to me somehow like the good white person of “please don’t look like me.” But the more you congratulate yourself for being the right kind of white person—well, I’m not sure what the second half of that sentence is, other than self-serving. See? There I go.

So I’m not rushing over to Chuy’s place to say any of that, because I have my own place to say stuff. And when I say stuff, it comes from the place I’m from. All those writers on Butler are on my bookshelves, too. I did not go to Columbia, but I read many of them in college. Others occupied the shelves in the houses where I grew up—they were as familiar to me as the names of the streets I passed on the way to school each day. When they showed up later in textbooks, they seemed like old friends.

I wrote the first half of this post back over a month ago, and perhaps I thought I’d keep writing and come to some grand conclusion. I haven’t. But I do want to acknowledge the place I come from. The grand conclusion is that here we all are, trying to figure out just how to be.