Bryan Way's Blog

May 9, 2023

Evolution of the Soul

It would be an understatement to say this will be different from what I generally post here, and it will most certainly veer past pseudoscience into the realm of dime-store philosophical claptrap. Consider yourself warned.

Having been raised in an environment with no discernable spiritual doctrine, I'm a lifelong, dyed-in-the-wool agnostic. Religion never particularly interested me as an explanation of existence or code of ethics, and the older I got, the more skeptical I became of its very human origins and rhythms: a structure that reinforces a set of behaviors with a vague and unprovable set of rewards or punishments after death, sometimes used for good, but most often used for bad. Interpretation of random, chaotic events as synchronic or representative of higher powers, such as when a rare good thing happens in otherwise terrible circumstances. I got it, I just never bought it. So my bespoke relationship with the unknowns of existence had a pretty rational sandbox.

The meaning of life is propagation. The "rewards" of life are simply hewn from a social/financial form of natural selection. There is no sentient, conscious, human-like being overseeing all existence; only sentient, conscious humans could conceive of such a limited "god". Good deeds versus bad don't add up on spiritual ledgers, but the karma reaped from what you sow is very real on a human-to-human level. Rather than seeking an answer about how or why we're here, we should marvel at the innateness of nature. Not just warm sunny days, trees, birds, streams, and oceans, but the infinite expanse of a living universe populated by sextillions of stars and the infinitesimal interactions of molecules that make it possible.

The soul, to me, was easy: it's the only thing about you that never changes. It is literally both your DNA and who you are. From birth to death, your cells die and replenish. You grow, learn, and challenge yourself. You can be struck with a disease that erases your personality, but you are always you. At least that's what I believed. Now, I'm not so sure.

We homo sapiens have forerunners going back billions of years. In only a tiny fragment of the age of the universe, we went from a quadrupedal gait to walking on the moon. Our evolution in the grasp of tools went phenomenally fast, and in doing so, as Matthew McConaughey's Rust Cohle suggests in True Detective , "nature created an aspect of nature separate from itself": consciousness. Suddenly, we stopped being animals who simply operated on instinct. We weren't just thinking, we were thinking about thinking. Then we started expressing those thoughts, first physically, then through art, then through language, and before we knew it, we created culture. In 20 quintillion tries on this planet, nature has not repeated this feat, at least not to the level of a species using invisible currency to acquire needless goods through a telecommunications object of astonishing sophistication used with offhanded ease. We can be so menacingly dumb and remain supported in society because of the unrelenting forbearance of the systems that allow us to survive.

When I think about that, I'm certain that my ancient ancestors saw an eclipse and were pretty sure the world was about to end. That thinking is simultaneously stupid and highly advanced: taking note of something extremely abnormal and internalizing what affect it might have on you. So when I consider humanity's relationship with the supernatural, I'm heavily on the side that repudiates interpreting random phenomena through the confirmation biases of consciousness. But when I consider the ubiquity of religion and spiritualism, I'm beginning to wonder if it's all an imperfect attempt to articulate innate feelings, inclinations, premonitions, and extrasensory perceptions we simply lack the existential vocabulary to adequately describe.

I'll make a simple example: how many times in your life have you heard about someone innately knowing about the death of a loved one? It's the sort of thing we hear frequently, and based on our beliefs, we either ignore or accept it and go about our day. But how often can we hear about something like that and ignore or accept that it's part of a pattern that has nothing to do with our beliefs? The most prevalent example of this is mothers losing a child. Fathers have connections with their children, for sure. But not the same way that mothers do. And I absolutely include adoptive parents in this equation: how much can you care about someone before it exceeds your ability to understand it?

I'm not suggesting that "love" transcends time and space, like McConaughey's Joseph Cooper in Interstellar (McConaughey again? Damn you!), and reject wholesale the notion of the perfectibility of man often explored in such sci-fi narratives. In viewing the entire history of life on this planet, a talking ape is patently absurd. Yet that's where we are. I accept Arthur C. Clarke's maxim that any sufficiently advanced technology is indistinguishable from magic. Can we say the same of a species? How can we project where evolution will take us, and which signs and signifiers we're living with now? We're still debating what consciousness means. Is it possible that the human race, having evolved a consciousness, is evolving methods for that consciousness to transcend the boundaries of known existence?

Allow me to pour some cold water: this notion is INSANE. It's certainly not backed by anyone with a reasonable assessment of human sociology or biology. How would you study this phenomenon? Abnormal, or parapsychology? The most advanced scientific minds of the day would rightly dismiss it as balderdash.

And yet.

And yet…

…there's still some part of us attracted to this notion. Consciousness, in all its complexity, favors the simplicity of believing that because it exists, it will continue to exist. Are psychics real? What about mind-readers? Do the dead exert influence over the living? How could any of this insanity legitimately play a part in a rational world?

Simple. We define the rational world through the crude lens of personal experience. And if we favor a scientific approach, we're married to observable, empirical evidence. But how often do we explode through a paradigm, challenging what we previously held to be sacrosanct through the embrace of heretical notions? A round Earth? Breaking the sound barrier? What do we know to be impossible now that's limited by our ape brain?

In short, I don't think we're turning into the X-Men . I'm still uncertain as to whether there's an afterlife, psychics, mind-readers, premonitions, or telepathy, or if the phenomenon surrounding those notions are interconnected. But if they are, I don't believe any answers lie in human-based religions based on deities who preceded us or authored our creation. I'm more inclined to believe we are evolving abilities that we, described in Ex Machina as a race of "upright ape(s) living in dust with crude language and tools", have yet to understand.

This essay was constructed by an upright ape who likes to tap letters on a plastic panel for the sake of personal enjoyment, fulfillment, entertainment, the hopes that it leads to salaried employment, and to distract him from his less than ideal existence making sure the local food purveyor has products available to customers every morning.

Published on May 09, 2023 11:32

March 10, 2022

Spuddle

If you hadn't noticed, there's been a pandemic.

spud·dle (ˈspʌdəl)

v

• To work tirelessly without achieving anything of worth.

• To put in a great deal of effort and achieve only very little.

• To make a lot of fuss about trivial things, as if they were important.

I won't beleaguer this long overdue post with musings specific to that development, but it'd be asinine to avoid it altogether.

I was riding high. Viva Video was astonishingly the nexus of a television pilot that seemed a pipe dream until the smoke cleared on its deliverance. Hot on the heels of copyrighting two screenplays after months of editing, I was starting to believe that I might have a chance to make a living off my creative endeavours; having distinctly made the acknowledgement that the video clerk life didn't have me on a provident path, I can only claim ignorance in the guise of ingrained optimism.

In early December of 2019, it looked as though Viva might be kaput. Miguel had long-since forsaken a salary, earning his living in a new career as a nurse and kicking over some of his own funds, only to thereafter rely on the financial assistance of an angel investor, but the store was stretched to a breaking point: our primitive rental software slammed into a time formatting/storage bug signaling our own bespoke Y2K, and, despite the recent upswing in first-rate publicity from our TV gig, profits had declined to a point of entropy. It was in this state that I became completely and utterly defiant: Viva was not going down on my watch, not without a fight. With the help of my valiant co-workers, I was intent on leading the charge for our resurgence. We were not going to manufacture a financial boon of hundreds or thousands in a single shot, I argued, but if we could improve daily intake through small, consistent ventures supplemented by monthly events, we would start making up the shortfall.

That August, me and my fiancée had brought our film screening and discussion venture State Street Movie Night to Viva, and it slowly began to gain traction with the customers. The following January, Viva sponsored a screening of Army of Darkness at a local theatre. Around this time, we began branding and marketing Viva merchandise like pins, stickers, magnets, mugs, and pint glasses. In February, the Viva crew hosted an Oscar party, bringing a princely sum to the store. The next SSMN thereafter was so crowded that there was no room for the staff to enjoy the movie. To start 2020, our profits had increased 25% relative to the previous January and February. Then came March.

Being shuttered for the pandemic wasn't a shock, per se, as we were all witnessing the natural progression that saw the world change. We mused it would be over in weeks or months, and we were wrong. Worldwide, these were hard times, and a true test of our society's fabric. By any metric, I had it easy. I'd hosted an SSMN birthday screening of Ghostbusters , then celebrated in a restaurant and had a few close friends over for a sedate party days before lockdown. For me, the ensuing weeks meant spending more time cooking meals, sleeping in, working on creative projects, and benefitting from government largesse while watching, reading, and hearing about the state of the world from the confines of home. Miguel, meanwhile, was thusly treated to a front row seat of the pandemic at its most grueling.

When it came time to reopen Viva in mid-June, the realities of healthcare work during a pandemic required Miguel to forswear shifts at Viva, and, as a result, I was tapped to captain the ship. For me, this brought about an amusing symmetry: when TLA Video was closing in October of 2012, the profusion of employees jumping ship made me the de facto assistant manager with Miguel insisting I be paid as such. Now, my inimitable qualifications put me in charge of operations. Navigating the good ship Viva through the post-lockdown world saw the addition of two new employees alongside our doughty interns. Though business was down, all was milk and honey in the day-to-day operations of the store, even when the occasional behind-the-scenes drama threatened to tarnish our luster.

Then, in September, my health took a turn for the worse. I developed a heart flutter that was annoying at best, terrifying at worst; one evening at a restaurant, after weeks spent ignoring the problem, I courted serious fears of having a heart attack before settling down at home. Around this time, I finally decided to find myself a personal physician after more than a decade without one. The next morning, I passed my first kidney stone. It was excruciating, but at least the trip to the hospital got me a blood test, urinalysis, and EKG that confirmed my heart disturbance as premature ventricular contractions, or PVCs. All in all, the health scare was decidedly mild and successfully goaded me into getting my medical affairs in order. A few close calls with COVID-19 later, things were back to normal, and by the year's end, I had four new short stories and a renewed vigor for the Life After series, so I naturally assumed I would remember 2021 as a year of rebirth.

Of January and February, I remember very little beyond the obvious. On my birthday in March, I encountered a series of random inconveniences; it's natural for the impact of a few things going wrong to feel heightened on one's birthday, but the compounding effect launched me into a despair I hadn't felt in ages. I had difficulty sleeping, concentrating on things that ought to bring me joy, and though I struggle now to recount all the details, this ennui enveloped me in the pointless desperation of everyday life alongside a complete and utter lack of hope for what lay ahead. I rarely reflect on moments where such feelings could be construed as prognostication, but looking back, this absolutely looks like a harbinger of what was to come.

While the waters remained still on the surface, sinister tides were churning beneath Viva. In between getting double-vaccinated, my stress level was steadily increasing, but whether I would be dragged out to sea or delivered to the shore became immaterial with the appearance of a tsunami on the afternoon of June 25th: Viva's lease had been cancelled. We would be forced to close effective in two months and there was absolutely nothing we could do about it.

Miguel shared the news with me first, giving me a few days in which to observe the store in its natural state with the knowledge of what was to come; while the two of us were effectively resigned to our fate, I had a feeling my co-workers would have a more sanguine view, and they did. Like a wizened Siddhartha, I ferried between helping Miguel organize a dignified conclusion and the staff's dreams of a grand revival before the former forecast came to bear and the floodwaters stripped us bare, but not before two months spent luxuriating in every last moment until we could smell the surf. Parties, pictures, videos, screenings, and a live musical ensemble colored what could only be described as a fitting sendoff. Not just to the store, but what it represented. What it meant to the people who filled it. And what it meant to my way of life.

At the final bell toll, I could comfortably say that I'd done everything in my power to enjoy those final weeks and walk away with my head held high as I became unemployed for the first time in my life. And I was going to make certain this time would be productive.

First, I sought to undertake several long overdue errands. A replacement windshield, repaired A/C fan, and inspection for my car. An eye exam for new specs and shades. A haircut. Revisiting my doctor for further analysis of my enduring sleep issues and PVCs, leading to blood work and a sleep study. Next, it was seeking a new venture and venue for Viva screenings, and trying to actualize the store's continuation in some form or another. Networking, chasing down leads, seeking publicity opportunities, and trying to find a job that would pay me to write. Whipping my published back-catalog into shape, including revised eBook formatting, seeking new reviews, overhauling background documents, revamping publicity materials, completing re-edits of my screenplays, and entering Noise Pollution into five competitions. I began exploring the possibility of creating audiobooks. Tinkered with improving some social media strategies. Reduced my alcohol consumption. Hosted my first-ever takeover of the Zombie Book of the Month Club . Worked out the kinks on my unemployment compensation. Betwixt birthdays, holidays, and my anniversary, I was just trying to find a job. Any job.

Let this caesura serve as an effigy for a lifetime of spuddling.

I am now employed once more. The PVCs are gone. And I've already been notified that my script has been discarded from two competitions. Between the fate of Viva, my repeatedly dashed dreams of a writing career, and despite my best efforts and generous portions of my time, practically everything for which I work seems destined to die on the vine.

That's not to say that I feel the time or effort was wasted. I had fun, gained experience, and brought entertainment, if not fulfillment, into the lives of many. Don't doubt for a moment that I am a personal optimist and joyful individual who has been extremely fortunate in life. Professionally, from my youth to the present, I have been chasing down a specious future, arguably working hard but not smart in pursuit of unattainable goals, and not only are these decades of failure finally catching up with me, I no longer see a path toward realistic success. It would be an evasion to call this anything else.

This doesn't mean I'm giving up, of course. Just that I'm finally going to be more pragmatic with my prospects; expect nothing, and you won't be disappointed. Perhaps this should become my mantra moving forward.

Published on March 10, 2022 12:27

January 9, 2020

The Rotten Tomatofication of America

I hate Rotten Tomatoes.

I hate the Tomatometer.

I hate what it has done to modern movie consumers.

In this acknowledgment, I wish to be unequivocal; I do not use the word hate freely or lightly. Hate is defined as "intense dispassion or dislike". This is, at best, a mild description of my feelings toward this institution: I despise, detest, abhor, and resent the existence of Rotten Tomatoes. It's been that way since well before it became a standard metric in consumer evaluation, and is likely to remain that way forever.

Let's backtrack. In the early days of Rotten Tomatoes, immediately following its acquisition by IGN, I didn't like it. I didn't know why, in the same way a teenager can't describe their loathing for the person their crush adores instead of them. The first glancing encounter around which my scorn congealed came from my mother: "I don't get it, are the movies supposed to be bad?" she innocently asked. No, I told her, but for the life of me, I couldn't articulate why a site distilling the ratings of critics automatically chose a name with such negative connotations: whether she knew it or not, my mother was supposing that the movies graded on this website had more in common with Plan 9 from Outer Space than Citizen Kane . And it was a reasonable assumption: the word rotten is synonymous with decomposition, mold, and stench. If the first word of a movie reviewing site is intended to conjure disgust, why would anyone assume its mission involves holding the medium to a higher standard?

This, alone, would help calcify that which is "rotten" in modern evaluations of film: that we start with an assumption that we should be appalled. I'm no blanket defender of the mainstream, and believe that movies can always aspire to a higher standard, but I believe wholly in remaining practical about the goals of any film regardless of genre, be it studio, independent, low-budget, no budget, foreign, or domestic. And I think we do them all a disservice by instantaneously associating them with "rottenness".

A further examination reveals that which is "rotten" in this site's aggregation technique: assuming that every critic on the planet were to rate films on a scale in which ★★★★★ is the standard, any review of ★★★ is designated "fresh", thus anything below it is "rotten". In other words, using the Tomatometer's infallible metric, if every critic on the planet gave a film a 3/5, it would be 100% fresh, sanctifying mediocrity in a manner appealing only to the film's marketing department. Such is the badge of honor that any film can be "certified fresh" as long as the majority of its reviews eclipse a halfway point, and the Tomatometer score can be dutifully affixed to posters and home media box art. Somehow, the image of a tomato on the cover of a work of art apparently translates as a seal of approval; to think, I used to scoff at the Oscars as an advertising tool!

It gets worse: since a ★★★★★ metric effectively creates a ten-point scale, the Tomatometer acclaims ★★★ and sneers at ★★½, meaning that Rotten Tomatoes adjudicates success or failure within the margin of a single point! The Tomatometer quantifies cinematic achievement as either "bad" or "good": there are no "ripe" or "edible" tomatoes, they can only be "disgusting" or "delicious". "Festering" or "flavorful". "Rotten" or "fresh".

I don't think the blame for this can be laid solely at the throne of the Tomatometer, but it is emblematic of attitudes endemic in modern film evaluation. Audiences at large place absolutely no premium whatsoever upon moderation; each new entry is either the best film ever made, or the worst. The intensity of the rhetoric in attack or defense has replaced reason and measure. All because a movie has to be either "bad" or "good".

How is the extermination of temperance in any way constructive to artistic dialogue?

I'm not averse to the notion of reviews in the aggregate, nor do I oppose the practicalities of doing so. In fact, I think MetaCritic does an outstanding job distilling critical ratings into scores that it then classifies as "good" (green), "bad" (red), or "middling" (yellow). Moreover, its process of arriving at those numbers and assignations not only makes logical sense, it leaves room for interpretation.

What Rotten Tomatoes does, on the other hand, is not "good". It is "bad". It eradicates a necessary middle-ground that determines what most people would define as "taste". The "consensus" it establishes is not productive, but destructive; anyone relying on the Tomatometer for quality film recommendations adheres not to high standards, but the involuntary whims of an aggregate that rewards anything north of mediocrity while decimating anything south. And the effect on anyone who views him or herself to be a specious authority on the subject has been profound: any film that excites a viewer is instantly hailed "a masterpiece", while anything even passively disliked is labeled "garbage".

You have to give them credit: they've marketed their services successfully enough that they've been adopted as an advertising arm of the industry, one that has made people predicate their willingness to spend two hours in the embrace of artistry or escapism on a "score" arrived at so apathetically it can hardly be said to have been "arrived at" at all.

Is there a solution? Not a practical one: we need to stop trying to distill mass appraisal down to a grade, because it's not the rating that matters, it's the conversation. I would personally rather listen to someone gush about their love for a movie I hated than try to shut them down with the statistics of a decaying fruit vendor. In many ways, that's what Rotten Tomatoes is: a specious adjudicator that does as much to sow division as it does to decimate the value extracted from a difference of opinion. I regularly see movies brought up for discussion turned victims of these vile assessments. The funny thing is, I also regularly see the distrust people harbor for the crisper variety: the metric is so stained by its inherent pessimism and unreliability that the label of "certified fresh" has begun to reek of putrescence.

I would argue that the model thusly collapses under its own pretensions: it is a site designed to simplify film assessment that needlessly complicates it in support of the notion that art itself is either "rotten" or "fresh", when such aggregation would be worth absolutely nothing if it weren't backed by the capital of valued literary assessments by critics. Those critics, by the way, stake their livelihood on making arguments for and against the values of any given film; they may render grades, but they are accompanied not by statements, but educated opinions with which we can freely agree or disagree.

My opinion on the matter? Art has no arbiter, and requires no stamp of approval that is not your own. Its value is derived from whether or not you like it, and why it has an impact on you. So stick with your gut and see what looks interesting, or find out about new movies from someone who knows you, rather than rely on a rancid berry juggernaut for advice.

Published on January 09, 2020 11:23

September 16, 2019

Movie Positivity

I’ve always loved movies. By the time my parents subscribed to HBO, and I realized I could watch one after another without commercial interruption, I was a goner. It was hardly surprising, then, that I would study film in college. Along the way, I worked as a projectionist at AMC Theatres, clerked at Blockbuster Video, participated in Temple University’s Los Angeles internship program, and, upon my return, started at TLA Video, during which I wrote movie reviews for Examiner.com. When TLA shuttered, I joined Miguel at Viva Video. Along the way, I was learning. About film. About other people. About myself.

Recently, I’ve been more proactive about dissecting the stages of my cinematic education, including a dissertation on elitism and populism. Like most, I started as a populist, consuming whatever commercial fare was fired my way. In adolescence, I began to reject that which shaped my childhood, until my eye was officially broken by Lost Highway in the late ‘90s. It forged my path toward elitism before, during, and after film school. It wasn’t until several years later, deep into the film odyssey and Letterboxd epoch, that a profound realization began to take shape.

Working at a video store changed me.

My job may be obsolete. It may be an edifice to nostalgia. I might frequently bemoan the visitors who stop by to reminisce without supporting us, but such visits are not altogether unpleasant, only because these sentimental tourists always recall video stores with fondness. The caché endures; if video stores had an impact on them, imagine what they've done to me. My long, slow realization was that I’d abandoned the confines of elitism and populism for egalitarianism; where once there was conflict, there is now an equal appreciation for either side. Though my childhood enthusiasm and subsequent education played an important part in that development, the true enlightenment came courtesy of a decade’s worth of customers.

Seriously. It can be enriching to watch, study, critique, and review film alone, but the medium is infinitely more enjoyable when it forges a connection. Friends and family may help shape our perception of art, but nothing is more valuable than engaging with strangers. Having been to the premiere of Transformers, I can speak to the adrenaline high of opening night in a theatre characterized by euphoric anonymity. The inverse of which is renting a movie; no one experiences that level of jubilation, but anonymity quickly disappears in the intimacy of a video store.

I can think of no simpler expression of what I’m getting at than this: A good video store clerk helps strangers find the movie they want. Perhaps I’m punch-drunk from a decade of hocking films, but I see an elegant beauty in that.

When face-to-face with a customer, I’m obliged to help. I ask questions. I listen. I try to see their point of view and grasp their sensibilities. I dredge a deep pool of cinematic knowledge to recover an ideal recommendation, then furnish them with it. Success comes with the singular satisfaction of making someone happy. If they dislike my suggestion, it is not necessarily that they failed to understand it, it’s more likely that I failed to understand them, so I resolve to try harder. Occasionally, I encounter customers too afraid or embarrassed to admit which movies they love, no doubt inhibited by their tastes being mocked, judged, or ridiculed. That this is their experience of film saddens me. That they have been treated this way infuriates me.

I’ve spent years engaging with film lovers of every persuasion, and regardless of age, sex, gender, genre, length, or language, I manage to find common ground in a love of movies, whether or not we agree. And even when we disagree, I try to do so with understanding and mutual respect. I am not alone in this approach, nor am I always perfect in practicing it, but I am an unabashed advocate.

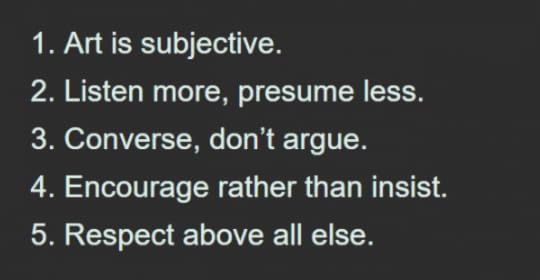

For lack of an existing designation, I’m calling it movie positivity. As I see it, these are its tenants:

1. Art is subjective.

I’ve seen the notion that “art is objective” bandied about, that its qualities can be judged on factual merits and ultimate truths. More often than not, this approach is weaponized, its adherents insisting that every work of art is either “good” or “bad”. It would be hypocritical of me to render definitive my own subjective view, that an “objective opinion” about art is oxymoronic bullshit, so let’s just say I’m not a fan. There is a certain narcissism buried in the supposition that art is objective, and those who espouse this philosophy are highly likely to presume their opinions are the standard to which all others must aspire. Personally, I think anyone claiming aesthetic authority is bigoted, or, at the very least, hopelessly vain.

My favorite analogy is that there is no Greek god Cinemos perched atop Mt. Olympus to whom we make films in effigy. No perfect, immortal authority proclaiming each offering “good” or “bad”. No critic, institution, publication, website, or aggregator capable of rendering an objective verdict. Time is the closest thing art has to an arbiter, and though consensus favorites may be canonized, they are not indemnified: we can watch Citizen Kane and acknowledge its importance to film history while being bored senseless.

What we like is exclusive, individualistic, and, above all, personal. Whether it’s food, clothes, music, books, politics, or lifestyle, we come to our own conclusions based on our environment, upbringing, family, friends, education, and experience. And none of it is inherently “right” or “wrong”. Of course, art does have objective properties: no one can argue whether Ryan Gosling is in Nicolas Winding Refn’s 2011 movie Drive . It is a fact. Whether his performance is any good, on the other hand, is subject to interpretation. And I would never imply that an opinion can’t be informed. An expert on cuisine, fashion, performance, literature, government, or social science may proffer an educated opinion in their field. Absent empirical evidence, however, it’s still just an opinion. A restaurant critic can tell you where to find three-star Michelin cuisine, and another might disagree, but if all you want is an In-N-Out burger, both opinions are worthless. Just as my opinion bears little weight in a conversation about The Fast and the Furious . I may not like it, but a lifetime of studying film doesn’t make me “right”.

2. Listen more, presume less.

We put a lot of stock in our own views, particularly where it concerns our passions. It’s a natural tendency, but if one subscribes to the notion that art is subjective, no amount of time, effort, or study will render an opinion definitive. Accepting the subjectivity of film - and that the experience of art is different for everyone - means embracing other people’s opinions, and one simply cannot do that without hearing them out. It’s not that we can’t or shouldn’t speak our minds. We simply need to take a moment in conversation to remember that listening is as important as talking. And while patience is a virtue of a good listener, it isn’t the only one; respecting the other half of the conversation is paramount.

This means accepting that someone talking earnestly about their love of film shouldn’t be judged. Our connection with art is so personal that sharing our passions is not unlike posing nude; more often than not, critique in a naked, vulnerable state engages our defense mechanisms. It’s easy to assume others have seen the movies that are important to us and guilt them when they haven’t, or interpret a difference of opinion as an attack. Many of us enforce these attitudes without considering their consequences; feelings of shame, a desire to withhold for fear of being ostracized, and defiant negativity. Why waste an opportunity to learn something and forge a connection with someone by affecting a high ground that is cheap, lazy, and pretentious?

For argument’s sake, say we hate superhero movies and encounter someone with a passion for them. What good would scolding do? Why criticize that person and make them feel bad? Why not ask questions instead of relying on our own presumptions? Why condescend when we have an opportunity to understand? We can give them our opinion without resorting to mockery, scorn, or weaponizing what they say. The more we listen, the better we can sympathize. And empathize. If nothing else, we get an opportunity to consider that other people have thoughts and feelings that matter. And the fewer presumptions we make, the better. We’ll never find common ground if we don’t look for it.

3. Converse, don’t argue.

When a disagreement arises on the subject of artistic merit, we have a natural tendency to antagonize any view we oppose. In the same way that voters in conflicting political parties manage to demonize their opponents and resist their policies, even if it means defying their best interests. Such arguments become a defense of a previously held position rather than an opportunity to gain a fresh perspective, and a disagreement based on mere self-preservation is in no way enriching to either side: if a quarrel over film is predicated entirely on one’s own views, we are, in effect, discounting the validity of anyone with whom we disagree. Why? What’s the point of verbal sparring in a subjective realm if we are only interested in self-defense?

In essence, conversation stands a better chance of productivity than argument; arguments require conflict, thus imposing the likelihood of attack and hostility, while conversations remain open to the possibility of disagreement just as much as they do understanding, sympathy, and empathy. And in my humble opinion, we are far more likely to listen in a conversation than we are an argument.

There can be no doubt that emotions tend to flare when opinions are discussed. Such passion is most often soured by disregarding the subjective, failing to listen, and leaning on that which we presume. Conversely, passion can emerge as both healthy and productive if we understand and embrace a difference of opinion rather than attack it.

4. Encourage rather than insist.

Even in an equitable conversation, it is still tempting to demand other film lovers embrace the films that matter most to us, especially the ones that garner awards, accolades, plaudits, big box office, or cultural caché, but what good comes from an approach that incentivizes peer pressure? In such situations, we do not consider the inclinations of those with whom we converse, we instead impose our views, often with the weight of consensus, insisting on things that have nothing to do with the other person and everything to do with enforcing conformity.

On the other hand, if we accept the subjectivity of art, listen without presumption, and converse instead of argue, our recommendations bear the weight of encouragement rather than insistence. Doing so allows us to better avoid transactional discourse, where we only take someone’s suggestions after they agree to watch something we’ve suggested; doing so purely for the sake of reciprocation cheapens an attempt at forging a connection, as such “trades” demand gratification rather than encourage mutual benefit. When sharing a love of film, no one wants to be held hostage by the demands of others; browbeating censure is rarely, if ever, received as positive enforcement, let alone motivation to enjoy any given film. It takes more time to understand someone and deliver bespoke recommendations than it does to fall back on the insistence that others like what we like, but the bond that comes from listening to, hearing, and understanding someone else is sacred.

5. Respect above all else.

After all these words, this should be self-evident, but it’s worth repeating: regardless of elitism or populism, taste or passion, education or emotion, it is imperative that we appreciate one another. Especially if we disagree. We often insult others with impunity, never stopping to consider the damage we cause, never considering how we will others to withhold, defend, and attack instead of acknowledge, share, and explain. It may be difficult to suspend our previously held positions when someone disagrees with us, or withhold retaliation when we perceive criticism, but that level of conscientious restraint renders as the simple human decency we call respect. What good comes from avoiding or suppressing it?

It’s worth acknowledging that some views are flawed, prejudicial, or offensive, and may be so hopelessly predicated on personal, social, or societal bias that they fail to be useful as a premise for conversation. Such patterns are unfortunate, difficult to break, and rarely improved upon by shaming or name-calling. We must do our best to remain positive and pragmatic in the face of disagreement, however; just as hate and violence beget more of the same, sinking to the depths of personal insults to impose our views on others isn’t productive. We must strive to be better.

As I said at the outset, I’ve always loved movies. And people who love movies. After years of embracing that, I believe that we can respect the views of others whether or not we agree. Whether we seek to stimulate or edify our emotions or intellect, whether we strive to experience love, hate, good, evil, order, chaos, right, or wrong from our cinematic diets, we seem attracted to the notion of taking sides, yet most often find the terms of our appeal on common ground. The purpose of movie positivity is to forge welcoming environments for film discourse, where we need not defend our opinions or attack others. Where we acknowledge that there is always more to learn about film, each other, and ourselves.

Published on September 16, 2019 11:40

June 26, 2019

The Middle Ground

My last post concerned the astonishing revelation that Viva Video, my place of employment, might become a television series that would prominently feature my co-workers and me. That post concluded prior to the first days of production.

This is what followed.

As previously indicated, I felt the experience too important to document. On some infinitesimal level, it was a gamble: would I kick myself for having failed at a contemporaneous memoir, or revel in the simplicity of letting it happen, safe in the knowledge that I couldn't forget what might rank among the most exciting days of my life?

As of now, I feel I made the right choice.

The crew loaded in and began production design in Viva Video on February 19th. It was then I had my second or third substantive discussion with Beau, our art director. Assiduous yet remarkably easygoing, Beau possesses the enviable skill of entertaining interruptions to states of seemingly zen-like concentration for casual conversation with the affect of an infinitely abiding friend. If I ever annoyed him, I never knew it. The same could be said for Tim, the rangy, raven-haired, soft-spoken producer on the fringes of the action, a man for whom "welcoming" might be too forbidding a term. Like so many I would meet over the ensuing days, their kind, unassuming temperament made their presence seem astonishingly normal. We were all at work, but even with the crew's passionate enthusiasm eclipsing my own, the store felt the same, just slightly busier and far more convivial. This left me unprepared for the beautiful chaos that followed.

On 2/20, I arrived at my 3:00pm "call time", only to bear witness to that chaos at its most surreal. In truth, even a modest departure from daily routine can be perceived as chaos. Bad traffic. Bad weather. Bad news. Bad people. But this was a completely different program: my video store was closed to accommodate the production of a television show. I unlocked the door, only to discover the freshly spruced foyer choked with tables, computers, crates, and wires, but most alarmingly, a massive monolithic black partition obstructing my view of the front counter. I walked past the blockage to find yet another stopgap: a black curtain, fully covering the doorway into Viva's main artery. I peeled back the veil to uncover madness.

The new release wall and the space before it were bathed in the sort of darkness generally reserved for strip clubs. What little light remained cast a torpor of ominous dimness, a hot red illuminating the basic contours like the embers of a smoldering cigarette, creating shadows where none existed, swallowing up everything to the peak of the front desks. There reigned the stark contrast of a warm whiteness that extended only as far as it needed to, highlighting an area between the counters and between the shelves, elsewhere faintly intermingling with that ubiquitous crimson, giving playfully dramatic definition to the mundanities of my every day existence. Red was the mood, and white was the stage. My stage. Mine, Perci's, Dan's, and Miguel's. At least a dozen people resided in those murky details, seeing to the cameras, lights, microphones, props, and sets with tireless, efficient aplomb. Before any lasting impressions could be forged, I was sent for hair and makeup by Ali, a genuine conversationalist with an industrious work ethic, hard-hewn yet infinitely inviting. It was a pleasure to be seated in her chair. You never wanted to leave.

A break followed the filming of Miguel's segment, during which I chatted up Paul, one of the two directors. Ashen, lean, and vibrant in his pensiveness, Paul and I discussed, among other things, dialogue in films that sets a tone. It was fitting, then, that we were broaching topics of a more personal nature when I was called upon to perform. I stood in the white light between the counters, staring down the barrel of a dark, indifferent camera lens, belching out suppositions about House , a film I'd never seen. I was okay. Dan, having arrived recently, went up next.

We broke for dinner, after which I was on again. Like my previous segment, I was to deliver a series of recommendations, this time based on They Live . Seemed easy enough, until I started thinking about it. To my credit, I'd developed these recommendations months prior without having consulted them again. To everyone else's credit, none of them knew that. I'd had a few knocks of whiskey to loosen up, but soon found myself tighter than a Gordian knot; the swigs of booze blazed up my esophagus, setting my heart alight with the panic of a sublime flop sweat. Each sentence I started bore no clear exit strategy, emphasized by the flatulent failure of Tourettic profanity. After what seemed like an eternity, our directors managed to stir my bleeding body off the wire, and though they were successful, each additional word out of my mouth felt like an apology. There were no two ways about it: I was awful.

Dan mercifully replaced me, at which point I went into full-on self-flagellation mode. Separated from the rest of the crew by the black monolith, I perched my throbbing skull against the cold, dark glass of the back door and began my autobiographical vivisection. How many thousands of dollars were being spent in this production for me to show up inarticulate and flabby, eating up precious time on camera with mealy-mouthed bullshit? How dare I waste the effort of these professional filmmakers by arriving unprepared? I categorically refused to blame anything or anyone other than myself, and rightfully so. The stage was set for me, and I blew it. I felt I was insulting the presence and function of everyone else who'd shown up to do their jobs, and I hated myself for it. No doubt about it, this was torture. But I've always found a bit of self-torture to be a good thing, lest I allow it to veer into self-harm; if I'm lucky, I glean something useful before causing any irreparable damage, and in this case, the takeaway was remarkably clear: stop giving them what you think they want, and start being yourself.

It was a deceptively straightforward platitude, but it worked like gangbusters. Following Dan, and my psychological self-laceration, I would be doing essentially the same act, this time adjacent to the Sci-Fi/Fantasy section rather than behind the counter. I was looser, freer, and less concerned with minutiae: any time you can get the crew to crack up, you feel like a stand-up slaying an audience, and there is no better feeling.

With the night's shooting completed, I returned home to an established routine I'd hoped to distract myself from overthinking the shoot: having recently acquired a blu-ray set of the original Star Trek movies, I intended to watch one a night, imbibing a few drinks along the way before writing a lengthy Letterboxd review and going to bed. This had been relatively successful the previous night, so I queued up Star Trek II: The Wrath of Khan and prepared for round two. By happenstance, I checked my phone and saw I had recently missed a call and voicemail from my mother. So late at night, I correctly intuited the reason: my grandfather had passed away.

I called her back immediately and confirmed this fact. After exchanging our shared grief, she made it clear that the forthcoming funeral arrangements would not interfere with the shoot. Hardly my most pressing concern. His passing accorded my viewing of The Wrath of Khan an additional resonance, after which I rendered my review and went to bed in anticipation of an earlier day.

As I drove to Viva on 2/21, I tried, and failed, to amp myself up. By the time I was behind the front counter, among the bustling crew, I occupied myself with menial, work-related tasks. I was not sad, or mournful, but my preoccupation with my grandfather's passing quickly became a fixation: no matter what I did, I simply could not stop thinking about him. He'd lived past 90, and although our relationship had been personified by the fractured family unit of which he seemed the indifferent patriarch, he'd made strides toward redemption in his autumn years, particularly with my mother. Having been put in charge of his estate, I did not envy her the task of executing his will, and worried about her rough road ahead. This consumed my thoughts throughout the early part of my day, from the drive in to being seated in the makeup chair to noticing that two executives from The Network had arrived to witness us in action. Just as we prepared to commence the day's shooting, I pulled our producer James aside.

I've mentioned James before, but never given him his due: he is, if nothing else, a man worthy of description. Tall and intense, with thick-rimmed glasses, a granite jaw, and a shock of pale, gravity-defying hair that served as a seemly barometer for his frenzied, ceaseless energy (alongside a booming, maniacal laugh), James embodies the properties of a charismatic huckster and an unflappable advocate for all things positive. It's a lethal combination; once plugged into his reactor, James could talk you into anything. In spite of this, my impending encounter felt like a betrayal of his exuberance. I simply told him that I didn't want to make a big deal about why I'd asked to speak with him privately, but if I sucked today, it would likely be as a result of my grandfather's passing. His commiseration was warm and enduring; he indicated he'd find a way to take our directors aside and apprise them of the situation. Once we returned to the set, he did so with casual elegance.

Fortunately for all of us, Miguel, Dan and I appeared as a trio in the ensuing shot, finding all three of us at our best. Our only task was to talk among ourselves about the movies we'd be showing, occasionally remembering to look into one of two cameras. Unbeknownst to the crew, they pulled the rip cord on three nerds design-built for the purpose. We broke for a costume change, then resumed. All told, the only differences from the norm were the cameras and the absence of customers. Having observed us in our natural element, one of the three arrivals from The Network smilingly admitted "I could never keep up with you guys."

This afforded me an opportunity to impress the values of Viva Video upon her: though the average video store clerk from '90s lore was a snide elitist, affecting an air of superiority while excoriating dissent, we respect anyone who loves film. I, for one, would never taunt someone confiding their favorite movie. Our opinions are immaterial so long as we share a love of the medium. Viva's recent fortunes lay on a bedrock of enthusiasm, passion, and knowledge, but I believe the heart of our appeal rests on an ability to receive customers without prejudice. We seek to not only embrace, but embolden film adoration in everyone who sets foot in our store. My declamation seemed well received; she and I spent long portions of the remaining two days talking movies.

Later in the day, while taking a break, I happened to be seated across from Kevin, our other director. Taller, broader, and decidedly more relaxed than Paul, his personality seamlessly ebbs and flows between engaging warmth and blasé wise-assery. He was an expert at taking the piss, the Brits might say, and having you love him for it. I can't recall where we started, but he ended up quietly and genuinely commiserating with me about my grandfather. The gesture was deeply appreciated. From my perspective, that dimension of this affair was a subtle thing. I did need to talk about it, but I did not want to turn the production into a pity party. I needed someone to know about my grief, but not everyone. Later, I learned that no one, not even Miguel, had heard about my grandfather's passing. In other words, my muted grief could not have found a better conduit than James, Kevin, and Paul.

Following our impromptu break, we did a few setups that would be built into the following day's shooting, most notably a mockup of the impending festivities in which Miguel and my co-worker Lisa would have an opportunity to talk shop on House . Dan departed, and Miguel was required later than I was, interviewing Susan, one of our more passionate, mercurial, and elder customers. At some point, several of my co-workers asked if I wanted to join them for Quizzo down the street. I did, and we won. First time ever. I returned to work victorious and another sheet to the wind, just in time to participate in the closure of the store for the night. I hung around with James to do some mild preparation for the party that would follow.

The "party" requires some explanation. The structure of our proposed show is predicated upon the archetype of late night movie hosts on television. In my view, the reason for the success of such programs throughout history is that they tapped into fandom: the hosts knew people dug what they had on offer. While we adore these scions of the cult classic, we endeavored to bring something new to the table. Viva Video is more than just a disc merchant populated by colorful characters, because unlike every other late night movie host who preceded us, we don't exist in a vacuum. We can't. We exist because of our customers, and that brand of symbiosis is endangered. It's why video stores have shuttered all over the world: it's easier to stay at home. What Viva Video lacks in camp and costumes, we make up for in honesty and humanity. Our store, and our customers, are what make us real. And when it all comes together for a screening party, we are inviting the world of fandom to sit down for a movie in our store. On a metaphorical level, we are not pandering to an audience, but asking them to watch with us. To join our community. To become a part of Viva Video. And we sought to embrace the terms of our appeal with the party on 2/22.

Heretofore in the production, I had forbidden any of my friends or family from visiting the set. The reason was simple: I had no idea what to expect, and I was terrified of any possible distraction. Though I am hardly encumbered by my work environment, Viva Video does encourage a certain rhythm, and there have been a few times in which my temperament has been cast asunder by visitors. By now, a different sort of rhythm had taken over: the environment and atmosphere of the production had become infectious. On the eve of the party, I hurriedly invited everyone I could on short notice, hoping to expose them to the palpable energy, joy, and industriousness overpowering my reservations.

While much of our crew had the benefit of working together previously, most of them were strangers to me on day one. But by day three, they were beginning to feel like old friends. Mike, whose tall, fit, infinitely laid back disposition threw me at first, became a favorite for exchanging dryly comic appraisals of on-set failures. And hugs. Drew, shorter and wiry with thick glasses and a beanie that seemed a permanent fixture of his scalp, was just as warm and conversational but twice as serious. Both were our bearded directors of photography, the former a natural Balbo, the latter concerted bushy. The third party to the facial hair party was another Kevin, our gaffer, whose mighty ginger thatch fails to conceal a handsome, quiet smile which coolly abides all types. A third Kevin, a lightly bearded chap under the gaff-electric wing, came off as reserved, nearly saturnine, but no less pleasant or agreeable. Jes, our willowy and demure props master, bore perpetually empathetic eyes, perfectly matched to her beguiling affect.

I admit it seems unlikely that such a group would feature no bad apples. In the end, I came away justifiably astonished: my personal meltdown accepted, I had absolutely zero negative experiences on set, and certainly nothing approaching distaste for any of the professionals inhabiting Viva. And on 2/22, the final day of our first leg, I brought in those closest to me to experience that which I could never describe.

My best friend Henderson arrived shortly after he'd finished work, adamant that his stay would be brief as he had no desire to be on camera. He was swiftly infected by the circus, donning a new shirt, being subsumed into a crowd scene, and staying hours longer than he intended. We enjoyed our free catered dinner and chatted away while the shooting continued in earnest; Miguel, as always, was given the heavy lifting in carrying the on-screen enthusiasm and could barely speak by the evening's conclusion. I was happy to remain a supporting player. Dan departed early to attend a film screening in the city, and would thus endure endless raillery for abandoning this once-in-a-lifetime event. One feature of this continuous party was a karaoke station at which all were encouraged to participate; mine was a form of humorous protest. Once freed from this responsibility, Henderson left and my parents arrived. After the passing of my grandfather only two days prior, I was overjoyed to bring them on set so they could bear witness to the pure jubilation of Viva Video's finest hour.

After all the madness that was the party, we settled in for the screening, prior to which I delivered an on-camera speech for at least the fourth time that day. Finally, after more than a decade being aware of its existence, I would see House . Midway through the movie, half the power cut; the lights were plugged into a timed circuit breaker, and a hasty intermission was called to fix the problem. Once fixed, the screening was resumed, after which we were asked to deliver impromptu reactions. I barely recall what I said, but definitely felt the film had been worth the wait. As the throes of production died down, I proffered sincere goodbyes and said what I felt, namely that I'd miss the action and the people when I returned to work the next day. It was an easy guess. Sunday saw me acting out the role of a lone steward tending an empty ballroom after the world's greatest party.

What followed was a lot waiting and talking. It was a familiar state, but having sampled the sweetness of production, I had become an addict. I wanted more, I wanted it now, and I wanted it forever. A few people on set, including Drew and Paul, jokingly indicated that Viva's staff would not be so receptive if the show got picked up and we had to endure them for three straight months. I begged to differ. The alternative is far less fun. And since we only had a week and a half until production resumed, we had plenty of time to ruminate on the alternatives. By the end of production, most of the crew commented that Viva Video ranked among their favorite gigs, an acknowledgement that included how inviting we'd been: every industry professional can relate tales of how quickly hosts for location work sour on the presence of cameras, equipment, crew, and chaos. We, on the other hand, adored it. And, perhaps more to the point, understood it. But that would come closer to the end than the middle. As it stood, there was still much to be said and done.

Our first episode, House , was largely predicated on Miguel's passion, but also in part structured around the notion that I hadn't seen it. Needless to say, this opportunity had presented itself; not only had I managed to avoid House despite a decade of knowing it was one of Miguel's favorites, but we'd also had months of pre-production in which I could've been brought up to speed. I ultimately decided it was better for me, Viva Video, and the show if we shot and broadcast my initial exposure. I hated the idea of watching House only weeks before production, then standing in front of the cameras with Miguel and Dan pretending it was some hallowed classic I'd always adored. At this point, our followup pilot, They Live , was lacking a comparable dynamic. It was discussed that two of our fellow employees, Paul and Steph, had not seen the film and would thus be terrific guinea pigs as I had been before. My only reticence lay in the fact that we had done two-male-clerks-pitching-another-clerk in the first episode, and thus three-male-clerks-pitching-two-other-clerks would lack freshness. It would render our initial gimmick repetitive and stale. Though we assumed we'd had two customers queued up for the screening - both would have been perfect - neither was available. Nobody panicked. I mean that. The plan was continuing as designed, but I felt They Live was missing a certain je ne sais quoi.

Enter Elyse.

Along with her parents, Elyse has been one of the more interesting Viva Video customers for years. We'd first rented to her at the age of four, when Miguel and I still worked for TLA Video. She was at once shy and exuberant, remarkably intelligent, and truly unique in temperament and appearance; I can think of no other customer who would engage in cosplay regardless of the occasion, and conversing with her was always a life-affirming reminder of the cinematic form as a fountain of youth, where theme, metaphor, plot, and character excite the electric reveries of adolescent wonder. And I sought to exploit her.

Just kidding. She's a terrific young adult, and several prior discussions with her parents yielded kernels that fueled my ultimate proposal: first, her mother indicated that Elyse had been self-regulating to a fault with her cinematic diet, and was nearing a point where she might want to investigate horror films. Naturally I was flush with ideas, but limited myself to a few suitable starting points. Then, irrespective, her mother called to indicate that Elyse was so fond of Viva that she'd like to work here. While I was flattered, her age remained a major hurdle; at 14, she would be legally ineligible to handle the adult product we carry. Without being specific, I insisted we'd be able to find some way to get her involved. The iron was hot. I struck.

There were some internal disagreements about Elyse's inclusion. Not sight-unseen, mind you. It was widely agreed that she was awesome and a qualified asset to the store, but the notion that They Live would provide her little in the way of cosplay opportunities and the fact that Miguel's interview with Susan had been an absolute grand-slam seemed to dim her potential impact. I held firm, arguing that the two pilots might be all we got, and that Elyse would bring an exciting new element to the production no matter her involvement. One way or another, it was agreed that we'd involve her, so long as her legal paperwork was completed in time. It came in under the deadline, much to my relief, and we had our new guinea pig.

With the plans now in place, phase two of the production was set to begin on 3/8. My best friend, previously reticent to stay on set for more than a few minutes, indicated that he'd be there for the entirety of both days. I was joined by my fiancée as well. The first day began with a comedian, Joe, doing his own interpretation of the protagonist from They Live . We'd become acquainted in the abortive first attempt to make Viva Video a show years back, where the lovably gruff and quick-witted punster portrayed a denizen of our adult room. Now, his rendition of this film's absurdly long fight scene would see him taking out his frustrations on a mock Redbox. I was not there to bear witness, but our crew informed me it was the funniest moment of the entire shoot. I believe it. The next gauntlet was a large, lengthy crowd scene where customers would leave the store to get ice cream next door, after which the stage was set for an interview between me and Elyse. And I had absolutely no idea what I was about to do.

To be fair, this was the mindset with which I entered production: it was both the reason for the cataclysmic failure of my initial They Live curations and my meteoric ascendance in the second rodeo. As Elyse and I sat down, dread flooded my bloodstream. What if I screwed up? What if she sensed I was screwing up and panicked as well? Worse, what if the interview somehow came off like I was leering at an adolescent? I took deep breaths as the crew finished the final lighting adjustments, then launched into it as though I was walking off a gangplank. I felt a rush of failure firing its way up my esophagus the moment I began to speak, but calmed down as I found a rhythm. She was nervous. I was nervous. But it worked. It's difficult to fake authenticity in front of a camera; this is, in part, why actors are paid handsomely, but I sensed that Elyse and I recreated the rapport that made me reach out to her family in the first place. We took a brief intermission, during which Paul whispered some direction in my ear. We continued, and it got better. When we finished, we shook hands. Moments later, she and her family were wrapping me up in a series of hugs. I was uncertain of what we got, but it felt good.

I can't remember the day's final setups, but I recall having difficulty sleeping that night. My brain had been contaminated by the shoot, and no amount of tossing and turning could sanitize it.

The penultimate day was 3/9, the final party. My first thought when I arrived at the shoot was that I wanted to take a moment to thank the crew for shepherding us through this adventure. Work continued. We tried to get every last item on our itinerary, but a few things fell by the wayside. We shot another party scene, where the camera followed Miguel as he interacted with various characters throughout our catalog room. Once finished, we broke for dinner one last time, at which point I was able to treat my brother and sister-in-law to a tour of our "set". As with all that had come before it, this was a delight. Finally, as we all settled in for the screening, I gave my final thanks to our crew, and we were underway yet again. The movie played like gangbusters, aided by two interruptions to keep the audience's energy up. Elyse enjoyed the experience, but came away underwhelmed. Steph too. I chalk that up as a win overall.

And all at once, the major shooting was over. I shared a drink with Kevin, Paul, and Kevin as we spent nearly an hour shooting the shit. I once again indicated that I would be crestfallen without them, having failed to realize that they'd be returning for pickups the next day. My mood improved drastically.

Without the staff, the crowds, and the pageantry, I once again returned to work on 3/10. No pressure, no moving parts, just work. And the final leg of production. It was glorious. I chatted up the crew, tried (and occasionally failed) to stay out of their way, and remained generally cooperative. Near the conclusion of my shift, the remaining crew indicated they'd be going out for a drink, ironically in the establishment at which James had first attempted to ingratiate Viva. Following the libations, the group splintered into a smaller subset, stopped into another bar, and finally availed themselves of Wawa for the evening's final repast. On my way home, I KO'd the first deer of my life, supposing that it must be karmic retribution for so many things going so well in such a short period of time.

Then, the waiting game commenced.

James, in his infinite enthusiasm and exuberance, was already deep into editing our material, which would be presented to The Network in various forms during the following months. Miguel got to watch each pilot in its entirety, starting with the House assembly. I got a chance to see They Live 's fine cut. Eventually, we'd all be treated to a robust suite of clips, known as "sizzle reels", which would prove - at least to us - that the idea had legs. They were exhibited to many a customer and friend, all of whom came away impressed. But the bulk of the work, at this stage, was above our pay grade; we'd tested our limits as video store clerks, fulfilling this role for six glorious days of inimitable spectacle, and now, in the interim, we would return to work.

So would the rest of the crew, for that matter, whose comparative daily grind I cannot imagine. Through James, I would occasionally hear that members of our erstwhile production crew had yet to experience anything as fulfilling as the Viva project in the months that followed. Some of them stop into the store on occasion, where we discuss status updates and reminisce about the shoot, clearly longing for more.

For the staff, the palpable excitement of a classy production would wane as normality settled in; only days later, we were once again informing the store's numerous visitors that yes, we are a video rental store, and yes, people do still rent videos. By this point, we'd grown accustomed to hearing their predictably insincere well-wishing, where passersby would bemoan the absence of brick-and-mortar rental boutiques, only to indicate their theoretical support prior to evaporating without spending a cent, and failing to see the fucking irony. Or, for at least the hundredth time, entertaining phone calls from people who see themselves as benefactors in their intentions to donate VHS tapes. We, on the other hand, like to think of ourselves as service providers and preservationists, not a dumpster for outdated analog media.

I digress. We embarked on an astonishing, improbable journey just a little over a year ago. Most attempts to pilot a television series are slow, laborious, painful, and die on the vine. At every stage of planning, pitching, and pre-production, where a simple 'no' could have sent us spiraling back down to earth, we ascended another step. We dreamed up a show, cemented a pitch deck, and solidified a budget. We planned one pilot, then two, which we shot in six days of hectic glory, during which everyone involved enjoyed their labors and made friends. We got out on time, on the money, and though the work was good, the edits were better.

As of this writing, we are still very much alive, patiently awaiting our deliverance. Whether it comes or not, you can be assured I'll have something to say about it.

Published on June 26, 2019 12:24

February 20, 2019

Snapshot Redux

A little over two years ago, I took stock of my life's periphery in a downturn.

My, what a difference 27 months can make.

It all began with the conclusion of the years-long quest to get my screenplays in fighting shape; following the failure of Life After: The Void , I dedicated myself to obsessively re-working all five scripts with the goal of meeting an ever-changing standard of quality. "Finishing" did not mean I felt any of them was perfect, merely ready, and the final keystroke meant that I could finally copyright the two originals, which I did on May 21st, 2018. The following weekend encompassed Memorial Day, during which I vacationed.

Two weeks later, both of my best friends experienced life-altering cataclysms: one ended a romantic relationship lasting nearly a decade, and the other was fired from a job he'd held for over five years. While my contemporaneous reality was tame by comparison, the return from my vacation heralded one of the strangest and most astonishing developments of my life.

As for my recently liberated friends, the first has since reconnected with an old flame, and the second is once more gainfully employed.

Now, the development at issue requires a bit of context: back in May of 2015, James Doolittle, a Viva Video customer and professional videographer, proposed a web series featuring me and my coworkers recommending movies based on the newly released beers of an acclaimed local brewery. We jumped at the chance to dream up film suggestions predicated on the styles and eclectic names of this brewery's latest libations, but despite our best efforts, the brewery showed little interest, and thus any future plans were scrapped.

Unbeknownst to us, James pitched his ideas (sans beer-pairings) to a friend working at a significant subscription television channel; essentially, James felt we were a concept worth exploring. When he didn't receive any return correspondence, James assumed his passions went unshared.

Fast forward to the first afternoon of my Memorial Day vacation three years later; James meets with this friend, who had since been promoted to a major cable television network (herein known as "The Network") and previously discussed James' nascent proposal with his superiors. To James' understanding, the concept of a show revolving around an independent video store owned and operated by passionate cinema junkies appealed to them. I learned of these machinations the Tuesday I returned to work. I cannot now recall my immediate reaction, but I would say it was somewhere between confusion and disbelief; though I always shelter a vestige of hope when I hear news so good it borders on preposterous, experience has afforded me a thick shield of skeptical cynicism.

The next step, I was informed, was to wait until The Network had a chance to consider how best to tackle their late-night schedule. James remained optimistic that Viva Video would be present in these plans, but there were lingering uncertainties as to whether we'd be filler in a larger programming block or headliners in our own.

Three weeks later, on June 21st, I was informed that James' initial pitch stuck the landing; The Network professed themselves delighted and requested a detailed proposal. What followed was weeks of impassioned insanity: each member of the Viva staff and James' production company took turns kicking around nebulous ideas until they began to coalesce. What was at first culled in haste was then re-worked, fine-tuned, revised, and proofread until we cemented a pitch deck. In it, we outlined a program in which we, the Viva staff, would host, hype, and get reactions to a film screening at our store with some of our passionate customers, only to use that footage as a prologue for showing the same movie on The Network. Like MST3K without the snark and Elvira without the camp.

On July 9th, we officially sent the deck to The Network. They acknowledged receipt the following day and indicated they liked our pitch, but needed to dedicate more time and thought to it. The waiting game commenced. Soon after, while imagining a boardroom of executives mulling our efforts at The Network offices, I was struck by the notion that this was fucking impossible.

In the ten years I have been a video store clerk, the rate at which I've been reminded that video stores are obsolete has increased exponentially; nowadays, at least three people per week stop in to remark how surprised they are that "places like this still exist", marvel at our inventory, thank us for still being here, indicate their notional support, and leave without renting or buying anything, never to return again, their visitations echoed in the short-lived dismay following the death of any Gen X institution: "Oh, it's a shame that thing I like but never use is going away…" Beneath the grand scope of what it means when modernization takes another victim, this is my job. I have been vaguely teased over still being a video store clerk, having had it suggested that there was no future in it, and that's not an argument I could refute. My clearly defined but specious goal was to remain at my job until I finished both my books and my screenplays, a notion that vaguely insinuated my desire to embrace a more profitable, less enjoyable career only after my artistic dreams had been crushed.

On numerous occasions, I'd had these conversations with loved ones who would subtly indicate they detected a reluctance to leave Viva. I'd offer my fanciful argument for staying, knowing full well that it was pie in the sky reasoning. In truth, I sought to avoid a mid-life crisis. I want to look back on my late 20s and early 30s confident that I fought for my creative endeavours, even if they didn't pan out. While that notion dominated the logic of staying at Viva, I will admit there was always something else keeping me there. I suspect it was a simple fear of a new and unknown life without it. If I believed in fate or destiny, I'd have said that, on some level, the providence of my path as a video store clerk was too great to be ignored, but that'd be total horseshit.

In essence, I finished the last of my unfinished creative goals in the same week it appeared that my unprofitable and professionally infertile job might suddenly become the most enriching and lucrative opportunity of my life. An astonishing turn of events, to say the least, and I was beginning to think my life couldn't possibly get any better.

Then it got better.

Within the relatively short span of these insane proceedings, I'd been enduring some problems with my living situation, an ordeal that presented its own set of headaches compounded by a lack of capital for a transition. Though I swore to myself that I wouldn't boomerang back to my parent's house after moving out, lodging with them quickly became the most viable option to save money for a smooth transition. I was apprehensive about having this conversation, but also completely unsurprised by their openness and generosity in welcoming me back, if need be. On July 12th, my father shared the details of my living situation with one of my relatives, who proceeded to astonish us all with an act of generosity that allayed my concerns for the immediate future. It would be apt to call it life-changing, as I now struggle to recall my state of mind before this deed compounded the astronomical developments with The Network. If nothing else, it made the waiting game a lot less tense.

Then, on August 23rd, The Network approved our pitch and asked James to start drawing up a budget. By this point, I was at Viva more often than my cohorts, so I had greater access to James in person, and he'd been a paragon of confidence. As a result, I would frequently assuage the reasonable doubts of my fellow employees, who still had yet to fully embrace our fortunes. James set a meeting for August 28th so we could discuss our next steps, namely selecting a film to screen and solidifying a budget. Since the meeting was at Viva, and I was working, I was 7½ hours early. James followed about seven hours later, having just gotten off the phone with The Network brass, who indicated they were "thinking 13-26 episodes". The visions of avarice inspired by these words were still nascent, as this latest batch of news, while transcendent, fell short of a full green light.

That would come on October 25th, when James texted me the words "We got it": we were to pilot two episodes, pending budget approval. All that was left was the planning, and that was James' department. There was little for the Viva staff to do, other than provide him with the occasional nugget of information or inspiration and continue being video store clerks. The necessity for two runs at this, rather than the usual one, arose when we considered that the initial film against which we would pilot might be too eccentric; there would be no doubting the staff's enthusiasm, but concerns were raised over its non-traditional narrative, obscurity, and peculiar brand of zaniness. The metaphor I favored compares taste in cinema to a community pool: most folks stick to the shallow end, and it was my belief that we best served them as shepherds to the deep. Our first film struck me as a jump off the high dive, and I was disinclined to play sink or swim with our collective destiny. My concerns were taken under advisement, but enthusiasm carried the day. Until it didn't, and we then sought to fortify our position by selecting something with cult credibility that fell a bit closer to the mainstream.

The process initially seemed to be on a fast track: shoot dates were being discussed as soon as the week following Thanksgiving, leaving the Viva staff scrambling to get the store in shape. Nothing firm materialized, however, and it was supposed that we'd try to schedule something by February. The possibility of the staff receiving some of The Network brass prior to shooting was broached at several points, but never came to fruition. The waiting game recommenced, and though despair never set in, we did court some lingering uncertainties. As stated from the beginning, this entire scenario felt like a dream, too astonishingly good to be true. Absent any bulletproof covenant or totemic evidence, we felt beholden to a fantasy. James allayed some of these concerns through sheer professionalism and an understanding of peculiarities that were above our pay grade: having had his services previously retained by The Network with fruitful results, their confidence in James' abilities and the pitched material solidified their confidence the project.