Movie Positivity

I’ve always loved movies. By the time my parents subscribed to HBO, and I realized I could watch one after another without commercial interruption, I was a goner. It was hardly surprising, then, that I would study film in college. Along the way, I worked as a projectionist at AMC Theatres, clerked at Blockbuster Video, participated in Temple University’s Los Angeles internship program, and, upon my return, started at TLA Video, during which I wrote movie reviews for Examiner.com. When TLA shuttered, I joined Miguel at Viva Video. Along the way, I was learning. About film. About other people. About myself.

Recently, I’ve been more proactive about dissecting the stages of my cinematic education, including a dissertation on elitism and populism. Like most, I started as a populist, consuming whatever commercial fare was fired my way. In adolescence, I began to reject that which shaped my childhood, until my eye was officially broken by Lost Highway in the late ‘90s. It forged my path toward elitism before, during, and after film school. It wasn’t until several years later, deep into the film odyssey and Letterboxd epoch, that a profound realization began to take shape.

Working at a video store changed me.

My job may be obsolete. It may be an edifice to nostalgia. I might frequently bemoan the visitors who stop by to reminisce without supporting us, but such visits are not altogether unpleasant, only because these sentimental tourists always recall video stores with fondness. The caché endures; if video stores had an impact on them, imagine what they've done to me. My long, slow realization was that I’d abandoned the confines of elitism and populism for egalitarianism; where once there was conflict, there is now an equal appreciation for either side. Though my childhood enthusiasm and subsequent education played an important part in that development, the true enlightenment came courtesy of a decade’s worth of customers.

Seriously. It can be enriching to watch, study, critique, and review film alone, but the medium is infinitely more enjoyable when it forges a connection. Friends and family may help shape our perception of art, but nothing is more valuable than engaging with strangers. Having been to the premiere of Transformers, I can speak to the adrenaline high of opening night in a theatre characterized by euphoric anonymity. The inverse of which is renting a movie; no one experiences that level of jubilation, but anonymity quickly disappears in the intimacy of a video store.

I can think of no simpler expression of what I’m getting at than this: A good video store clerk helps strangers find the movie they want. Perhaps I’m punch-drunk from a decade of hocking films, but I see an elegant beauty in that.

When face-to-face with a customer, I’m obliged to help. I ask questions. I listen. I try to see their point of view and grasp their sensibilities. I dredge a deep pool of cinematic knowledge to recover an ideal recommendation, then furnish them with it. Success comes with the singular satisfaction of making someone happy. If they dislike my suggestion, it is not necessarily that they failed to understand it, it’s more likely that I failed to understand them, so I resolve to try harder. Occasionally, I encounter customers too afraid or embarrassed to admit which movies they love, no doubt inhibited by their tastes being mocked, judged, or ridiculed. That this is their experience of film saddens me. That they have been treated this way infuriates me.

I’ve spent years engaging with film lovers of every persuasion, and regardless of age, sex, gender, genre, length, or language, I manage to find common ground in a love of movies, whether or not we agree. And even when we disagree, I try to do so with understanding and mutual respect. I am not alone in this approach, nor am I always perfect in practicing it, but I am an unabashed advocate.

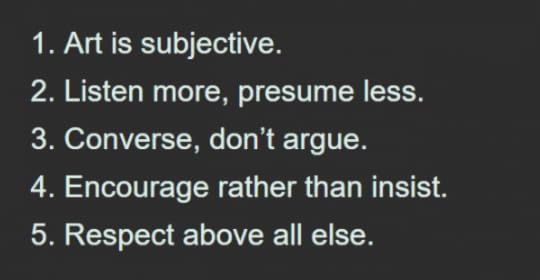

For lack of an existing designation, I’m calling it movie positivity. As I see it, these are its tenants:

1. Art is subjective.

I’ve seen the notion that “art is objective” bandied about, that its qualities can be judged on factual merits and ultimate truths. More often than not, this approach is weaponized, its adherents insisting that every work of art is either “good” or “bad”. It would be hypocritical of me to render definitive my own subjective view, that an “objective opinion” about art is oxymoronic bullshit, so let’s just say I’m not a fan. There is a certain narcissism buried in the supposition that art is objective, and those who espouse this philosophy are highly likely to presume their opinions are the standard to which all others must aspire. Personally, I think anyone claiming aesthetic authority is bigoted, or, at the very least, hopelessly vain.

My favorite analogy is that there is no Greek god Cinemos perched atop Mt. Olympus to whom we make films in effigy. No perfect, immortal authority proclaiming each offering “good” or “bad”. No critic, institution, publication, website, or aggregator capable of rendering an objective verdict. Time is the closest thing art has to an arbiter, and though consensus favorites may be canonized, they are not indemnified: we can watch Citizen Kane and acknowledge its importance to film history while being bored senseless.

What we like is exclusive, individualistic, and, above all, personal. Whether it’s food, clothes, music, books, politics, or lifestyle, we come to our own conclusions based on our environment, upbringing, family, friends, education, and experience. And none of it is inherently “right” or “wrong”. Of course, art does have objective properties: no one can argue whether Ryan Gosling is in Nicolas Winding Refn’s 2011 movie Drive . It is a fact. Whether his performance is any good, on the other hand, is subject to interpretation. And I would never imply that an opinion can’t be informed. An expert on cuisine, fashion, performance, literature, government, or social science may proffer an educated opinion in their field. Absent empirical evidence, however, it’s still just an opinion. A restaurant critic can tell you where to find three-star Michelin cuisine, and another might disagree, but if all you want is an In-N-Out burger, both opinions are worthless. Just as my opinion bears little weight in a conversation about The Fast and the Furious . I may not like it, but a lifetime of studying film doesn’t make me “right”.

2. Listen more, presume less.

We put a lot of stock in our own views, particularly where it concerns our passions. It’s a natural tendency, but if one subscribes to the notion that art is subjective, no amount of time, effort, or study will render an opinion definitive. Accepting the subjectivity of film - and that the experience of art is different for everyone - means embracing other people’s opinions, and one simply cannot do that without hearing them out. It’s not that we can’t or shouldn’t speak our minds. We simply need to take a moment in conversation to remember that listening is as important as talking. And while patience is a virtue of a good listener, it isn’t the only one; respecting the other half of the conversation is paramount.

This means accepting that someone talking earnestly about their love of film shouldn’t be judged. Our connection with art is so personal that sharing our passions is not unlike posing nude; more often than not, critique in a naked, vulnerable state engages our defense mechanisms. It’s easy to assume others have seen the movies that are important to us and guilt them when they haven’t, or interpret a difference of opinion as an attack. Many of us enforce these attitudes without considering their consequences; feelings of shame, a desire to withhold for fear of being ostracized, and defiant negativity. Why waste an opportunity to learn something and forge a connection with someone by affecting a high ground that is cheap, lazy, and pretentious?

For argument’s sake, say we hate superhero movies and encounter someone with a passion for them. What good would scolding do? Why criticize that person and make them feel bad? Why not ask questions instead of relying on our own presumptions? Why condescend when we have an opportunity to understand? We can give them our opinion without resorting to mockery, scorn, or weaponizing what they say. The more we listen, the better we can sympathize. And empathize. If nothing else, we get an opportunity to consider that other people have thoughts and feelings that matter. And the fewer presumptions we make, the better. We’ll never find common ground if we don’t look for it.

3. Converse, don’t argue.

When a disagreement arises on the subject of artistic merit, we have a natural tendency to antagonize any view we oppose. In the same way that voters in conflicting political parties manage to demonize their opponents and resist their policies, even if it means defying their best interests. Such arguments become a defense of a previously held position rather than an opportunity to gain a fresh perspective, and a disagreement based on mere self-preservation is in no way enriching to either side: if a quarrel over film is predicated entirely on one’s own views, we are, in effect, discounting the validity of anyone with whom we disagree. Why? What’s the point of verbal sparring in a subjective realm if we are only interested in self-defense?

In essence, conversation stands a better chance of productivity than argument; arguments require conflict, thus imposing the likelihood of attack and hostility, while conversations remain open to the possibility of disagreement just as much as they do understanding, sympathy, and empathy. And in my humble opinion, we are far more likely to listen in a conversation than we are an argument.

There can be no doubt that emotions tend to flare when opinions are discussed. Such passion is most often soured by disregarding the subjective, failing to listen, and leaning on that which we presume. Conversely, passion can emerge as both healthy and productive if we understand and embrace a difference of opinion rather than attack it.

4. Encourage rather than insist.

Even in an equitable conversation, it is still tempting to demand other film lovers embrace the films that matter most to us, especially the ones that garner awards, accolades, plaudits, big box office, or cultural caché, but what good comes from an approach that incentivizes peer pressure? In such situations, we do not consider the inclinations of those with whom we converse, we instead impose our views, often with the weight of consensus, insisting on things that have nothing to do with the other person and everything to do with enforcing conformity.

On the other hand, if we accept the subjectivity of art, listen without presumption, and converse instead of argue, our recommendations bear the weight of encouragement rather than insistence. Doing so allows us to better avoid transactional discourse, where we only take someone’s suggestions after they agree to watch something we’ve suggested; doing so purely for the sake of reciprocation cheapens an attempt at forging a connection, as such “trades” demand gratification rather than encourage mutual benefit. When sharing a love of film, no one wants to be held hostage by the demands of others; browbeating censure is rarely, if ever, received as positive enforcement, let alone motivation to enjoy any given film. It takes more time to understand someone and deliver bespoke recommendations than it does to fall back on the insistence that others like what we like, but the bond that comes from listening to, hearing, and understanding someone else is sacred.

5. Respect above all else.

After all these words, this should be self-evident, but it’s worth repeating: regardless of elitism or populism, taste or passion, education or emotion, it is imperative that we appreciate one another. Especially if we disagree. We often insult others with impunity, never stopping to consider the damage we cause, never considering how we will others to withhold, defend, and attack instead of acknowledge, share, and explain. It may be difficult to suspend our previously held positions when someone disagrees with us, or withhold retaliation when we perceive criticism, but that level of conscientious restraint renders as the simple human decency we call respect. What good comes from avoiding or suppressing it?

It’s worth acknowledging that some views are flawed, prejudicial, or offensive, and may be so hopelessly predicated on personal, social, or societal bias that they fail to be useful as a premise for conversation. Such patterns are unfortunate, difficult to break, and rarely improved upon by shaming or name-calling. We must do our best to remain positive and pragmatic in the face of disagreement, however; just as hate and violence beget more of the same, sinking to the depths of personal insults to impose our views on others isn’t productive. We must strive to be better.

As I said at the outset, I’ve always loved movies. And people who love movies. After years of embracing that, I believe that we can respect the views of others whether or not we agree. Whether we seek to stimulate or edify our emotions or intellect, whether we strive to experience love, hate, good, evil, order, chaos, right, or wrong from our cinematic diets, we seem attracted to the notion of taking sides, yet most often find the terms of our appeal on common ground. The purpose of movie positivity is to forge welcoming environments for film discourse, where we need not defend our opinions or attack others. Where we acknowledge that there is always more to learn about film, each other, and ourselves.

Published on September 16, 2019 11:40

No comments have been added yet.