Matt Rees's Blog - Posts Tagged "sonnets"

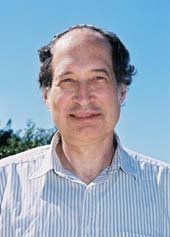

The Writing Life: Warwick Collins

The riskiest thing for a writer to do is to try to enter the head of a great genius by making that genius the narrator of a novel. Why? Because if you aren’t a genius of at least similar proportions, it won’t ring true. Think of the tedious melodrama that passed for the life of Michelangelo in “The Agony and the Ecstasy”. When that genius is the greatest writer of all time, the risk to our present writer increases proportionally. Warwick Collins, a British novelist and poet, took that chance when he made William Shakespeare the narrator of his novel The Sonnets. But it was worth it, because Warwick succeeded and The Sonnets is by far the most beautiful novel of recent years. It’s also an astonishing examination of why a writer writes and of how a literary work can change along with the life and loves of the writer. That makes Warwick the perfect author to answer the questions posed here in The Writing Life. He has some surprising ideas.

How long did it take you to get published?

I was fortunate that my first book, a sailing thriller called Challenge, was bid for by eight publishers. It was eventually published by Pan/Macmillan

Would you recommend any books on writing?

I don’t know any books on writing that I would recommend. The best way to learn about writing, I suspect, is to read as much good literature as one can.

What’s a typical writing day?

I’m one of those annoying people who feel fresh when they wake up, so I try to put in a minimum of one and a half hours before breakfast. If I feel up to it, I’ll return at various stages in the day. But I find writing is quite a nervous and energy-sapping process, and often I find that after my morning efforts I need the rest of the day to recover and be ready for the next early morning attempt on the blank screen.

Plug your latest book. What’s it about? Why’s it so great?

My most recent novel The Sonnets is an attempt to describe Shakespeare’s life from 1592-4, the years in which the London theatres were closed by threat of plague, and the 29-year-old Shakespeare was forced back on his own resources. He was fortunate to find a patron in the young Earl of Southampton. Those were the years in which many of the other playwrights died of violence (like Marlowe, killed in suspicious circumstances in a pub or Kyd, put on the rack) or of poverty, like Greene. Shakespeare emerged from those turbulent times to become the leading playwright on the Elizabethan stage. During those plague years, too, it is widely believed that Shakespeare wrote the bulk of his great sonnet sequence. I’ve integrated 32 full length sonnets into the text of my novel. I also added two “imitation” sonnets – both carefully flagged up as imitations, by the way. It was fascinating attempting to compose those imitation sonnets, and I think it helped me to gain an insight into the way sonnets are constructed, and how the very tightly defined form imposes on the content.

How much of what you do is formula dictated by the genre within which you write, and how much is as close to complete originality as it’s possible to get each time?

So far I’ve always been criticized by UK and American corporate publishers for NOT writing to a formula and for constantly changing both the subject matter and the style with which it is approached.

Who’s the greatest stylist currently writing?

For prose, Cormac McCarthy; for dialogue, Elmore Leonard.

Who’s the greatest plotter currently writing?

Philip Pullman, for His Dark Materials trilogy.

How much research is involved in each of your books?

I thoroughly recommend writing the first draft of the book before one does detailed research. This appears the wrong way round, but I believe it is still vastly more effective. Knowing the subject matter of the novel greatly narrows the research area, and the result is that the research in that area can be highly focused and detailed. The Rationalist and The Marriage of Souls were both set in the eighteenth century, about which I knew very little. I could have spent years reading up about the eighteenth century and only used a fraction of my laboriously acquired knowledge in the novels. But, for example, once I knew that Silas Grange, the protagonist, was a physician of “modern” outlook (for the times), I could research the area of medical practice in far greater depth than otherwise would have been the case, and virtually all of it was useful.

Where’d you get the idea for your main character?

A number of writers I have talked with are inspired by people whom they’ve met. In my own case, I get interested in an idea first, and after that it’s more a matter of trying to build up a character from the circumstances. In the case of The Rationalist, for example, some of the few things I did know about the eighteenth century were that it was a time of loss of religious faith, of the rise of science, and the loosening of sexual mores – in that way a reflection of our own times. It seemed interesting to me if Grange had elements of a modern scientist in his character, was perhaps a touch obsessive, pragmatic, rational, thorough, and if the femme fatale who brought him down, Mrs Celia Quill, was something of a proto-feminist.

What’s your experience with being translated?

So far pretty good. I’ve been fortunate that my foreign language publishers have chosen good translators.

Do you live entirely off your writing? How many books did you write before could make a living at it?

I have lived mostly off my writing for about 20 years, but I’m unusual in that most of my income has come from foreign language translation/publication, and from occasional forays into screenwriting.

How many books did you write before you were published?

My first published work was a series of poems published in the magazine Encounter. I wrote two novels before Challenge was published. They both seem to me now to be somewhat juvenile, and I would have no interest in either of them being published.

What’s the strangest thing that happened to you on a book tour?

During a tour of Germany for the German edition of my novel Gents, my publisher was based in Munich. Gents is a novel about three immigrant West Indians who run a urinal in London, and spend much time trying to suppress the “cottaging” (sexual activity between men) which goes on in the cubicles. Each of the West Indian main characters is religious and something of a family man, too, so this background activity is somewhat shocking to them. Although I am not gay myself, Gents was fortunate to receive favorable reviews from the gay press, and from West Indian reviewers. I don’t know whether my German publisher, a leading feminist, was being mischievous, but while on book tour she booked me in at a famous gay hotel in Munich. That was a very interesting experience.

What’s your weirdest idea for a book you’ll never get to publish?

The weirdest idea I have had for a book was Gents, and I did publish it, and am glad that I did.

Poetry from the ‘driest’ book of the Bible: Yakov Azriel’s Writing Life

A few years ago I was at a literary conference near Tel Aviv. I found an eclectic mix of writers on the panel with me. I’m a crime writer. You wouldn’t expect me to be paired with a writer of poetry who takes his inspiration from the stories of the Bible. But as Yakov Azriel read his poetry, I sat beside him feeling that no contemporary poems had ever touched me as deeply. They’re full of the knowledge of the Bible the Brooklyn-born poet garnered during his studies at Israeli yeshivas and his four decades living here. There’s something else though: they bring to life the hills and desert around Jerusalem. To an outsider, it can often seem strange that so many people are attached to a place that’s stark and rather ugly and certainly not a nurturing environment for sustaining human life. With Yakov’s poems I think you’ll find a sense of what the place means. Here’s his interview, followed by a wonderful poem from his newest book.

How long did it take you to get published?

It took a few years of submitting my first manuscript of poetry to different publishers until my first book of poetry was published.

What’s a typical writing day?

I make a living by working as a teacher, so during the daytime I do not have the opportunity to write. I usually try to write in the evenings and at night (especially at night); I try to write one new poem a week.

Plug your latest book. What’s it about? Why’s it so great?

My latest book is entitled Beads for the Messiah's Bride: Poems on Leviticus, and it was published in June by Time Being Books (a literary press specializing in poetry). Like my two previous books of poetry (Threads From A Coat Of Many Colors: Poems On Genesis and In The Shadow Of A Burning Bush: Poems On Exodus, each poem in the book begins with a Biblical verse and the book is structured as a running commentary, starting with chapter 1, verse 1 and ending with the last Biblical chapter.

This book was challenging for several reasons. My first book focused on the different characters in Genesis, and I especially tried to focus on the gaps in the Biblical narrative (for example, who was Abraham's mother?) or to give a voice to figures who are silent in the Biblical text (such as Dinah, or Joseph's wife Asenat). In the poems on Exodus, the many events in the Biblical narrative itself (the enslavement in Egypt, the Ten Plagues, Passover, the splitting of the Red Sea, etc.) readily lent themselves to poetry.

In contrast, the Book of Leviticus is considered to be "drier," without the drama and large cast of characters of the first two books of the Bible. One device I used in order to grapple with this difficulty was a conscious effort to fuse the English literary tradition with the Jewish-Hebrew heritage. For example, the first chapters of Leviticus deal with sacrifices; I decided to write a Petrarchan sonnet for each sacrifice, a sonnet that is a prayer, modeled after the "Holy Sonnets" of John Donne. In the end, one book reviewer felt that this book was the most powerful of my three published books (eventually, we will be publishing five volumes of poetry, one for each of the Five Books of Moses).

How much of what you do is:

a) formula dictated by the genre within which you write?

b) formula you developed yourself and stuck with?

c) as close to complete originality as it’s possible to get each time?

I write poetry in all forms: mainly free verse (like most 21st century poets), but also formal, metric poems — sonnets, sestinas, villanelles, ballads, etc. Each poem has a life of its own, and it is the poet's duty to help each poem find its own voice. Just as a sculptor has to liberate the statue that is hidden in a block of marble, so the poet has to liberate the poem hidden on the empty page and grant it breath.

As I said, all my poems are based on the Bible. The Biblical verse is like an iceberg, with 90 % of its meaning under the surface; my job is to try to get under the surface.

T.S. Eliot said that there is little good religious poetry being written today because the religious poet tends to write what he thinks he ought to feel instead of what he really feels. All good poetry must be sincere. So part of my task as a poet is to be sincere, as much as possible.

What’s your favorite sentence in all literature, and why?

This is a very difficult question to answer! One sentence that really resonates for me in English literature is when Hamlet describes his father to Horatio in Act I, Scene II, and tells him that "He was a man." What a wonderful example of praise, love and understatement in four simple words.

In Biblical literature, one sentence that that I find very powerful occurs right after the scene in which the prophet Nathan tells King David the parable of the poor man's lamb (First Samuel, Chapter 12) and King David, incensed, says that this man deserves to die; after Nathan exclaims, "You are the man," David does not argue but admits, "I have sinned."

What’s the best descriptive image in all literature?

Again this is very difficult to answer, but I think that Dicken's description in Little Dorrit of the banquet scene in Rome in which Mr. Dorrit relives the past he has been trying so hard to conceal, and calls out loud to Amy, speaking about the turnkey and his imprisonment in the Marshalsea prison — this is certainly one of them.

How much research is involved in each of your books?

I have been "researching" my books all my life.

Where do you get your ideas?

This is a very good question. Often in the middle of the night an idea comes; I have to write it down, and the following evening, I work on it.

Do you have a pain from childhood that compels you to write? If not, what does?

No, I do not think that it stems from a childhood pain. Why do I write? Ask me why I breathe. The great German poet Rilke said that no one should write poetry unless he would have to die if it were denied him to write. Perhaps this is too strong (for me at least) but I cannot imagine a life for myself without writing.

What’s your experience with being translated?

I have translated several of my poems into Hebrew. However, you could perhaps claim that all of poetry is a kind of translation of dream language into waking language.

What’s your weirdest idea for a book you’ll never get to publish?

To write it in Yiddish.

And now, some poetry: from Beads for the Messiah's Bride: Poems on Leviticus (Time Being Books, 2009)

THE SCAPEGOAT

“And Aaron shall place both his hands on the head of the scapegoat and confess upon it all the sins of the Children of Israel and all their crimes, whatever their transgressions; they will be put on the head of the scapegoat, which will be sent off to the desert in the hands of the executioner.” (Leviticus 16:21)

Bright crimson ribbons tied between his horns,

A clanking, clinking bell around his neck,

His back bedecked with ornaments of silk —

Why did the priest place hands upon my head,

Then trembling shout a list of sins and crimes?

I bet I know: they want to crown me king,

A wise and noble king who never dies.

An orchestra of Levites play their flutes,

Their golden harps, their ten-stringed lutes, their drums,

Their silver trumpets as he is taken out —

Why I alone am sent to Azazel?

And who or what the hell is ‘Azazel’?

I bet I know: they think I am an angel,

A pure, immortal angel full of grace.

Out of the Temple precinct packed with crowds,

And out the narrow lanes of Jerusalem,

And out Damascus Gate, toward desert cliffs —

Why am I brought here to this mountain peak?

Why rip the crimson ribbons from my horns?

I bet I know: they wish to worship me,

I bet I —