Matt Rees's Blog - Posts Tagged "interviews"

Somali pirates, Sri Lankan slaughter, and capybara meat in a roquefort sauce

I was a guest on the BBC World Service's The World Today programme this morning. It's an eclectic news show which ranges from Somali pirates, to the Sri Lankan government's bloody new assault on the Tamil Tigers, and the taste of capybara meat (a clandestine delicacy in Venezuela apparently, although the BBC's reporter sampled it in a roquefort sauce, which strikes me as a terrible mistake.) You can listen here. The other guest is a most sympathetic fellow, Kenyan journalist Salim Lone.

Published on April 12, 2009 06:16

•

Tags:

bbc, capybara, east, interviews, lanka, middle, palestinians, somlia, sri

Crime Always Pays, Punk

One of my favourite blogs is Declan Burke's excellent Crime Always Pays, which does for Irish crime fiction what the famous toucan does for Guinness. As a Welsh crime writer, I assume I'm the next best thing to an Irish crime writer, so Declan includes me today in his long-running interview series "Ya Wanna Do It Here or Down the Station, Punk." Find out what I'd want in return for strangling puppies and biting the heads off chickens....

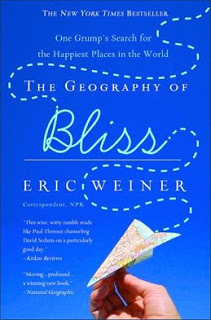

Whingers and Warm Guns: Happy-Guru Eric Weiner's Writing Life

What’s happiness? A large income, Jane Austen said. Absolute ignorance, according to the delightfully morbid Grahame Greene. Or John Lennon’s less delightfully morbid warm gun. Whatever else it is, happiness is done to death. But where it is? That’s something new. The genius of Eric Weiner’s New York Times bestseller “The Geography of Bliss: One Grump’s Search for the Happiest Places in the World” is to change the way of searching for happiness. Instead of looking for ways to make himself happy (the typically American individualistic approach to joy), he went out to find places where other people were happy. That way the former NPR correspondent (I got to know him when he was Mideast bureau chief, but he was based in India, too, for a time) was able to identify broader characteristics of a society that create happiness. He found, of course, that being Swiss helps (they trust everyone around them and therefore don’t have to worry and watch their backs). Being Moldovan on the other hand definitely doesn’t help -- everyone cheats, nothing's fair = miserable place. On his journey Eric also ditched email. But he broke that rule for the sake of my blog, and I’m glad he did.

How long did it take you to get published?

It took me three weeks to find an agent and publisher. It took twelve years for me to settle on an idea that I was passionate about.

Would you recommend any books on writing?

No. I think the best way to learn to write is to write. Reading (everything and anything) helps, too. So does coffee.

What’s a typical writing day?

I wake up bright and early, and by 8:00 a.m. settle into my office. Then I check my e-mail. Then I check Facebook. Then I check a few of my favorite blogs. Then I break for lunch. Usuallly, after lunch, I will do some actual writing before calling it a day.

Plug your latest book. What’s it about? Why’s it so great?

You're asking a writer to plug his own work? Okay, if you insist. My book, The Geography of Bliss, is brilliant because it takes a fairly tried subject, happiness, and gives it a new twist. Most happiness books focus on the what of happiness; I was interested in the where. Which are the world's happiest countries and what can we learn from them? And--did I mention?--the writing is brilliant! Funny and serious at the same time. I would highly recommend it. Really.

How much of what you do is:

a) formula dictated by the genre within which you write?

b) formula you developed yourself and stuck with?

c) as close to complete originality as it’s possible to get each time?

Mainly b), I think, with a smattering of c). My genre, broadly speaking, is travelogue. It is an odd, self-loathing genre. Many of the great travel writers don't like to be called travel writers. I think that's because travel writing sounds fluffy and inconsequential. At least bad travel writing is like that. Good travel writing is simply good writing that happens to use place as its main construct. In my work, I try to fashion a slightly new genre, the travelogue of ideas. In that sense, my book isn't really travel book at all. It's a book about the nature of happiness that uses geography as a way to get at this mystery.

Where is your favorite place to write?

I like coffee shops. The background din, oddly, helps me focus. After a while, though, I get antsy and feel the need to move. I might write in two or three different places in a single day. After all, I am a travel writer. Place matters.

Who is your favorite travel writer?

Jan Morris. She can get to the heart of a place in a few sentences. She is opinionated, but not obnoxiously so. She puts herself in her writing but never gets in the way of a good story. And she can be funny in all the right places.

What do you do if you are stuck?

I drink more coffee. If that doesn't work, (and it usually doesn't) I go for a walk. If that doesn't work (and it usually doesn't) I read what I have written aloud. I tend to write for the ear, and reading aloud can help me regain my rhythm. Also, I recently discovered a wine called "Writer's Block." It's a very nice Zinfandel.

What do you read for pleasure?

I like big fat books that tackle big fat topics. I'm currently reading Peter Watson's Ideas; A History of Thought and Invention from Fire to Freud. It's easily 800 pages. I'm still in the fire bit.

How much research is involved in each of your books?

An awful lot. For The Geography of Bliss, I read everything I could get my hands on about happiness, from Aristotle to Marty Seligmen, the poo-bah of the "science of happiness." I camped out at a university library for weeks on end. For a while, I was concerned that I was over-researching, but now I dont' think there is such a thing. Many morsels from my research made their way into the final manuscript.

What’s your experience with being translated?

My book has been translated into 13 languages, The publishers send me copies, which is nice. I can't understand a word of them,. for all I know they did a terrible job of translating. But they look nice on my bookshelf. Especially the Korean edition. Very colorful.

Do you live entirely off your writing?

I do make a living off my writing. I consider myself very fortunate.

How many books did you write before you were published?

This is my first one. Non-fiction, though, is a lot easier to get published than fiction.

What’s the strangest thing that happened to you on a book tour?

I had just completed an interview with a radio station in Portland, Oregon, when the interviewer said, "That was really great, Do you want to smoke some weed?" It's true. I might have taken him up on it, but I had a book reading in a couple of hours, so I politely declined.

What’s your weirdest idea for a book you’ll never get to publish?

I'd like to write a travel book about time travel. I would go back in time to an age when there still were undiscovered places to explore and write about them. I'd also buy some choice real estate in Manhattan. Then I'd travel back to the present and live large.

Published on June 10, 2009 01:11

•

Tags:

east, eric, happiness, interviews, journalism, life, literature, middle, nonfiction, weiner, writing

When poets do the talking

A new book examines the lives of Palestinian poets

By Matt Beynon Rees - on GlobalPost

JERUSALEM — Whenever Palestinian and Israeli artists get together for public “dialogues,” it always seems to end with the Israelis saying, “We’re sorry,” and the Palestinians responding, “Screw you anyway.”

That was how it went at a literary conference in the Jerusalem monastery at Tantur where I moderated a couple such discussions two years ago.

Except for the opening session.

The day began with a reading by Taha Muhammad Ali, a poet who lives in Nazareth, and his translator Peter Cole, a native of New Jersey and now a Jerusalem resident. Taha, who was then 75 years old, recited several of his poems, which Cole read in English.

Taha was avuncular and bumbling, endearing him to the audience of international publishers. But his poetry was deceptively incisive and personal, transcending the sense of victimization that would color the panel discussions for the rest of the day. Somehow he seemed to be the only one that day who had anything real to say.

"Don’t aim your rifles / at my happiness, / which isn’t worth / the price of a bullet,” Taha read. “My happiness bears / no relation to happiness.”

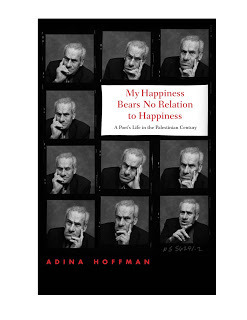

The warmth and intelligence of Taha’s readings drove Adina Hoffman, a Jerusalem-based writer and wife of translator Cole, to plan a biography of the poet (“My Happiness Bears No Relation to Happiness: A Poet’s Life in the Palestinian Century,” Yale University Press). Only then did she discover that, despite all the ink spilled on the Palestinian issue over the years, no one had ever written a biography of any Palestinian poet.

So she expanded the book. Using Taha as the central figure, she constructed the intersecting life stories of writers as diverse as Mahmoud Darwish, the "national" poet whose death last year prompted weepy editorials around the world, and Rashid Hussein, the most original and tortured of them, who died alone and drunk in New York 30 years ago.

Hoffman’s book is a way for readers to get around the usual stereotypes of the Palestinians as they’re portrayed in the cliches of their political struggle. She looks at the fascinating day-to-day, emotional history of this troubled people as told through their dynamic poetic culture.

“One can get a different idea of Palestinians as people through the history of their poets,” Hoffman told GlobalPost. “Poetry and poets occupy such an essential role in Palestinian society: Throughout much of the last century, poetry has served as one of the most important means of political and social expression for the Palestinian people — and the poets who’ve given voice to that impulse are central to the culture.”

Their poetry forms a gap in our knowledge of the Palestinians because of the way reporters cover their story — focusing on the violence and pyrotechnics and screaming, rather than on what people actually feel beneath it all.

“So much of the news coverage of the Palestinian story winds up treating them as a faceless group — whether a group of terrorists or a group of downtrodden victims,” Hoffman said. “I wanted to offer a view of Palestinian life that depicted as precisely and deeply as possible the full human range of feeling and complexity that exist in that culture.”

Hoffman uses Taha’s story as the framework for an alternative telling of Palestinian history, eschewing the slogans of political leaders and focusing on the soul-searching of young poets and writers.

You might think that would draw you away from reality into the realms of fantasy. But, as I’ve discovered in writing a series of Palestinian crime novels based on real stories I’ve reported, it’s only when a writer examines the underlying emotions of his subject that he uncovers the truth.

“The truest poetry is the most feigning,” Shakespeare wrote. Journalists, from whom we’re accustomed to getting our information about the Palestinians, aren’t supposed to be “feigning” at all. The result: no poetry and, often, no truth.

Hoffman’s telling of Taha’s story is particularly important because his life encompasses almost every element of the Palestinian experience. Born in 1931 in the village of Saffuriya, his family was expelled during the 1948 war which founded Israel. They fled to Lebanon, snuck back to Nazareth, and became refugees within Israel. He saw the devastation of war, too, on a visit to Lebanon in search of his childhood sweetheart.

Taha supported his family by running a souvenir shop for tourists visiting the town where Jesus grew up. He slowly developed a literary style that was at odds with traditional, highly formulaic Arab verse. Neither did he follow the incantatory public style of Darwish and the best known Palestinian poets.

Hoffman observes that Taha’s largely free verse (which many Palestinians rejected as simple prose chopped up into lines) is based around a classical Arabic concept of “a difficult, elusive, or even inscrutable simplicity.”

That simplicity is embodied in the poet’s peasant background, which Hoffman tells in vivid detail. Much of the book’s early chapters are devoted to life in Saffuriya, before the village was replaced with an Israeli community.

But it isn’t yet another regurgitating of Palestinian suffering. Her portrait of the village illustrates the richness of life there, showing how the memory of Saffuriya was part of “the world that surrounded these poets and that inspired them to write,” as she said.

It’s the remembrance of that world that dominates Taha’s poetry even six decades after Saffuriya ceased to exist. Hoffman’s account preserves the memory by recounting it and by introducing readers to the poetry that grew out of it.

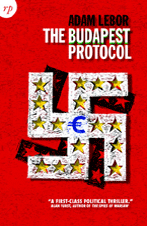

Culture and harshness in Central Europe: Adam Lebor's Writing Life

Political writing at its best highlights the unexpected changes in parts of our world that are hidden to us. That’s true of writing about the corridors of power in our own capital cities, but it’s even more of a factor for a writer like Adam Lebor whose work – fiction and nonfiction – has captured the dynamism and double-dealing of Central Europe, in particular. Because I live in the Middle East while he lives in Budapest, Lebor first came to my attention with his wonderful “biography” of Jaffa, the ancient port city on the Mediterranean coast, “City of Oranges: Arabs and Jews in Jaffa.” It was a masterful stroke to profile this town, rather than Jerusalem or even Tel Aviv, which tend to attract the attention of writers more readily than a historic city that’s now a slum filling with liberal yuppies. It shouldn’t have surprised me, then, that Lebor’s new novel The Budapest Protocol, which I reviewed recently, would take an issue that many think of as boring and bureaucratic – the expansion of the European Union – and make it immediate and vital, linking it to the demons of Europe’s past through Nazism and genocide. The novel is firmly in the tradition of great British writers like Eric Ambler, Graham Greene, and John LeCarre. Like them, Lebor knows that Central Europe’s cultured side comes with an accompanying harshness that makes for great drama.

How long did it take you to get published?

My first non-fiction book, ‘A Heart Turned East’, about Muslim minorities in Europe and the United States, was published in 1998 by Little, Brown, UK. It was commissioned so was published a few months after I wrote it. That was a fairly straightforward process. Since then I have written another five non-fiction books, all of which were commissioned.

Fiction, however, was a very different story. I first started writing the book that would become The Budapest Protocol in Paris in the winter of 1997. It was rejected by numerous publishers before I finally found one, Reportage Press, that would actually spend the time to tell me how to fix it. I always knew I needed the attention of a good editor, but apparently most publishers nowadays expect a perfectly formed novel to land on their desks, which is ridiculous.

Would you recommend any books on writing?

A search on amazon.co.uk for ‘writing a novel’ brings up 20,625 results. Most of the authors of these books are not well know novelists, because successful novelists are writing novels, not books about how to. That said, I have found ‘The First Five Pages’, by Noah Lukeman, very useful. Lukeman is a well-known American agent, and the book is full of good advice, from a commercial viewpoint. I would recommend it for anyone who is serious about getting published. I also like ‘Writing A Novel’ by John Osborne, which is enjoyably cantankerous but full of good advice.

What’s a typical writing day?

Breakfast with the Today programme on my Evoke internet radio, invaluable for keeping in touch when you live abroad - I am based in Budapest. Spend morning probably doing journalism or admin. Usually the muse arrives after lunch, and a good writing session will go from about 3pm to nine or ten at night. If it’s really flowing I will wake up in the morning with a plot solved or idea for a chapter plan that somehow my subconscious has sorted out while I am asleep and then I am straight back in the book.

Plug your latest book. What’s it about? Why’s it so great?

The Budapest Protocol is a conspiracy thriller that was inspired by a real American intelligence document from 1944. The document, known as the Red House Report, is an account of a secret meeting of Nazi industrialists in the Maison Rouge hotel, Strasbourg, where they planned for the Fourth Reich, which would be an economic imperium not a military one. That was the inspiration - I then used my twenty years reporting experience in eastern Europe to work out how that might actually happen. There is also a love story with several sexy, difficult girls and atmospheric scene setting in present day Budapest.

How much of what you do is formula dictated by the genre within which you write?

Thrillers are to some extent quite formulaic. The hero needs inner conflict to drive his outer battle with larger sinister forces. He needs to face and overcome repeated obstacles, each time getting in more and more danger. The trick is use the formula to make the structure work while making the setting, atmosphere and narrative drive powerful enough. Alan Furst, the master, gave me some advice: “Start with a murder and make sure the boy gets the girl” which was very useful.

What’s your favorite sentence in all literature, and why?

“Heshel was watching him through the window of the car and smiled thinly as their eyes met. Here is the world, said the smile, and here we are in it.” A line from my favorite book, Dark Star, by Alan Furst. Dark Star is an espionage thriller set in late 1930s Europe. That sentence is subtle, telling, and somehow opens a world of the imagination.

What’s the best descriptive image in all literature?

It was a bright cold day in April and the clocks were striking thirteen.

Who’s the greatest stylist currently writing?

Alan Furst. Less is more.

Who’s the greatest plotter currently writing?

David Ignatius, author of Body of Lies and The Increment. I would also add Stieg Larson, who sadly is not writing any more.

How much research is involved in each of your books?

The Budapest Protocol did not demand any specific research as I have covered this region for twenty years. My non-fiction books, like ‘City of Oranges: Arabs and Jews in Jaffa’ about Jewish and Arab families in the ancient port demanded many weeks of research, hours of interviews and gaining the trust of the families.

Where’d you get the idea for your main character?

The fact that he is a foreign correspondent, who lives in Budapest, who is obsessed with sinister conspiracies and who is entangled with beguiling but unsuitable women and whose first name is four letters beginning with ‘A’ is entirely coincidental.

What’s your experience with being translated?

Fine. I have been translated into eight languages, but I don’t really check what they have done to the book, even in languages I know.

Do you live entirely off your writing? How many books did you write before could make a living at it?

Now, yes. But that is combined with journalism for big papers like The Times, Economist etc. I think it would be very difficult just to live off books, and I like the change of pace with journalism. I value my connection with The Times, it opens doors and my assignments give me ideas for books and characters.

What’s the strangest thing that happened to you on a book tour?

I suppose it’s probably not that strange and happens to other authors but I was amazed that after two sell out events at the Edinburgh book festival with about 180 people in the room I only sold a handful of books. Why pay eight pounds to watch the author when you can buy the book for that?

What’s your weirdest idea for a book you’ll never get to publish?

I cannot reveal that as it’s such a good idea it may yet hit the shelves one day!

Poets central to Palestinian culture

My favorite Palestinian poet is Taha Muhammad Ali, a quietly bumbling presence when he reads his poems, but a deceptively intelligent writer. The warmth and intelligence of Taha’s readings drove Adina Hoffman, a Jerusalem-based writer, to plan a biography of the poet (“My Happiness Bears No Relation to Happiness: A Poet’s Life in the Palestinian Century”, published this April by Yale University Press). Only then did she discover that, despite all the ink spilled on the Palestinian issue over the years, no one had ever written a biography of any Palestinian poet.

So she expanded the book. Using Taha as the central figure, she constructed the intersecting life stories of writers as diverse as Mahmoud Darwish, the "national" poet whose death last year prompted weepy editorials around the world, and Rashid Hussein, the most original and tortured of them, who died alone and drunk in New York 30 years ago.

Hoffman’s book is a way for readers to get around the usual stereotypes of the Palestinians as they’re portrayed in the cliches of their political struggle. She looks at the fascinating day to day, emotional history of this troubled people as told through their dynamic poetic culture.

Here’s a brief interview with Hoffman I conducted last week:

Matt: Did it surprise you there was no biography of any Palestinian poet?

Adina: It did surprise me, but then again maybe it shouldn’t be so startling. I write in the book about the various challenges of composing the biography of a Palestinian subject—and high on that list is the lack of a Palestinian archive, or archives. Many of the writers (Taha Muhammad Ali and Mahmoud Darwish included) come from peasant backgrounds, and that peasant culture relied on the oral rather than the written record. And the little that may have been written down was destroyed in 1948. So I had to rely on a combination of interviews and British and Israeli archives (which were essential to my work, though the perspective presented there is obviously not Palestinian), as well as photos and books on a hundred different related subjects.

So it is, in a way, a luxurious genre: you can’t just pick up a pen and paper and write a biography like this. You need to have access to these archives and books and photographs as well as access to various interview subjects. A writer sitting in Beirut or even Nablus would have a harder time simply getting to these sources—whether because of checkpoints and borders or because the Israelis might not let them in. Meanwhile, those who might have access to the archives might not have the various languages required to make sense of them, or the desire to write about Palestinian culture… and so on and on.

Matt: With my Palestinian crime novels, I’ve tried to write about the real Palestinians as I’ve come to know them over the years, rather than the stereotypes with which they’re portrayed in journalism. Were you trying to do something similar?

Adina: I do agree that one can get a different idea of Palestinians as people through the history of their poets. First of all, because poetry and poets occupy such an essential role in Palestinian society: throughout much of the last century, poetry has served as one of the most important means of political and social expression for the Palestinian people—and the poets who’ve given voice to that impulse are central to the culture. But I was also interested in writing about the world that surrounded these poets and that inspired them to write. In Taha’s case, much of his poetry is grounded in his village, Saffuriyya, which was destroyed in 1948. The whole first part of my book is devoted to trying to conjure that village on the page. It’s not just about the destruction of that village, in other words; it’s also about the very rich and complicated life that existed there before ’48.

So much of the news coverage of the Palestinian “story” winds up treating them as a monolithic, basically faceless group—whether a group of terrorists or a group of downtrodden victims. I wanted to offer a view of Palestinian life that depicted as precisely and deeply as possible the full human range of feeling and complexity that exist in that culture, as in any culture. To put it more simply, I didn’t treat the Palestinians in my book as representatives of anything but themselves, as a group of individual human beings.

Matt: Anyone who’s written about the Palestinians knows that it can be a minefield, particularly when you face the public on a book tour. You’ve been in the US recently to promote “My Happiness Bears No Relation to Happiness.” What kind of response do you find there?

Adina: Apart from one or two predictable knee-jerk responses, I’ve been very pleasantly surprised by the openness of readers to the book. People seem quite eager to read about Palestinian life and culture in a way that gets past the standard version that’s put forth in the media. And on top of that, I think they’re just drawn to the incredible poignancy and richness of Taha’s story—and the story of so many of the people his life has intersected with over the years.

Published on June 30, 2009 23:52

•

Tags:

east, interviews, israel, life, middle, nonfiction, palestine, poetry, reviews, writing

“What happened to the third little pig, Daddy?”: Bob Burke on pig detectives and his Writing Life

Anyone who’s perused the crime fiction section of their bookstore knows the joy of finding something original among the tired old shelves of loner detectives who play by their own rules on the mean streets of some dingy inner city. The clichés of the genre were uppermost in my mind when I chose to write about Omar Yussef, a schoolteacher and detective in a Palestinian refugee camp on the edge of Bethlehem. Irish writer Bob Burke has not merely blown the crime formula away like Dirty Harry's Magnum – he’s used them as the source of much of the fun in his great new novel “The Third Pig Detective Agency.” Bob’s first book in the series is populated by characters from nursery rhymes and fairy tales. His detective is the surviving Little Pig (after the Big Bad Wolf ate the first two) and his mean streets are in Grimmtown (as in The Brothers Grimm of fairy tale fame). In my review, I wrote that “Third Pig” is “undoubtedly the most whimsical hardboiled detective novel ever written, and it's utterly delightful.” As you’ll see from this interview, so is Bob Burke.

How long did it take you to get published?

Since I started taking writing a bit seriously, about three years – but I was lucky.

Would you recommend any books on writing?

In terms of what I got out of them, I’d suggest two: Stephen King’s On Writing for its very straightforward, no nonsense approach to putting pen on paper (as well as being a very honest autobiography) and Carole Blake’s From Pitch to Publication which shows how the industry works from first draft, through getting an agent, contracts, publication etc. Both are invaluable for anyone starting out.

What’s a typical writing day?

During school term I get my sons to school and am back at the house by 9:30 (probably still asleep). I’m definitely not a morning person so after a refueling session with coffee, I start by checking email, blogs, twitter and doing any publicity bits and pieces that may have arisen (aka arseing around on the web). Once I’ve evolved from zombie to something approaching human I start on whatever story I happen to be working on and work through until about 5pm, with numerous refueling stops along the way (coffee, must have more coffee). I never worry about word counts as long as I have something on paper (or on PC to be more accurate). Eventually something tangible appears from the combination of brain, caffeine and willpower.

Plug your latest book. What’s it about? Why’s it so great?

Harry Pigg – sole survivor of the unfortunate Three Little Pigs incident and self-styled master detective – is hired by Aladdin to locate his missing lamp. The trail leads Harry through a maze of unreliable informants, mysterious strangers, not-so-dastardly villains, occasional beatings and an unpleasant encounter in a sewer. Is it great? Most people that have read it seem to like it, which is all I can ask for. It’s certainly a different take on the traditional detective novel.

How much of what you do is:

a) formula dictated by the genre within which you write?

b) formula you developed yourself and stuck with?

c) as close to complete originality as it’s possible to get each time?

The formula for the detective story (particularly the hard-boiled type) is so well established that it provided the perfect template to work with – and take the piss out of. I just wanted to approach it from a slightly skewed angle but still work with all the conventions that people are familiar with (and probably expect). I’d like to think that my take on it has some degree of originality that will make readers want to come back to it again (and again and again and…)

What’s your favorite sentence in all literature, and why?

Squire Trelawney, Dr. Livesey, and the rest of these gentlemen having asked me to write down the whole particulars about Treasure Island, from the beginning to the end, keeping nothing back but the bearings of the island, and that only because there is still treasure not yet lifted, I take up my pen in the year of grace 17__ and go back to the time when my father kept the Admiral Benbow inn and the brown old seaman with the sabre cut first took up his lodging under our roof.

It’s not great literature but that one line, the opening to “Treasure Island,” opened up the world of story to me. With that book I went from reading stories that were short and illustrated to a more intimidating volume that was rich with text and had no pictures. Almost immediately I was sucked into the story, all sense of intimidation gone as the narrative carried me into a true adventure story. Even now, Treasure Island remains one of my favourite reads.

The line that made me laugh the most (and still does) is from The Colour of Magic by Terry Pratchett: Rincewind had been generally reckoned by his tutors to be a natural wizard in the same way that fish are natural mountaineers.

What’s the best descriptive image in all literature?

If I might be permitted to go all literary and pretentious, the passage that sends shivers down my spine is the last page or so of Finnegans Wake by James Joyce where he describes the River Liffey flowing into the sea. Yes, most of the rest of the book is impenetrable and I don’t claim to have made any sense of it but that one piece is accessible, evocative and so beautifully written

Who’s the greatest stylist currently writing?

John Connolly. His ability to mix wonderful prose, engaging characters and compelling storylines make me want to weep every time I read one of his books. He’s also managed the difficult task of injecting his otherwise dark stories with a vein of black humor that never seems forced or inappropriate.

Who’s the greatest plotter currently writing?

Jeffrey Deaver. Take an impossible situation, throw in a series of plot twists and end with a satisfying and logical conclusion and you have a recipe for one of his books.

How much research is involved in each of your books?

A quick shufti through the Bookmarks section of my web browser shows one link: an online version of Grimm’s Fairy Tales. Make of that what you will! In fairness, there’s such a rich treasury of nursery rhymes and fairy tales that I can “gleefully molest” (as one reviewer put it) that research isn’t as necessary as it might be for anything else I may write.

Where’d you get the idea for your main character?

I’d finished telling The Three Pigs to one of my sons and he asked, with typical child curiosity, “what happened to the third pig after the story was over?” I didn’t even have to think about it, the image of that third pig becoming a detective sprang almost fully-formed into my head. All I had to do then was work with it and develop a story.

Do you have a pain from childhood that compels you to write? If not, what does?

I think that discovering the power of storytelling through early exposure to Treasure Island and subsequently with Edgar Rice Burroughs and Tolkien fuelled my imagination and gave me the urge to tell stories. Unfortunately there’s no hint of any trauma in the orphanage, wicked stepmothers or being sent out to steal by a shifty guardian in my childhood.

What’s the best idea for marketing a book you can do yourself?

Flog the web to death. Blog about it, twitter about it, link to blogs with similar themes. Also, local papers are always interested in the “local lad does good” angle and will more than likely welcome an approach, which may lead to other media taking an interest.

What’s your experience with being translated?

I’ll let you know if it ever happens!

Do you live entirely off your writing?

Not yet. I do some part time IT training in tandem with my writing but hopefully one day…

How many books did you write before you were published?

One. Again, I know how lucky I’ve been.

What’s the strangest thing that happened to you on a book tour?

A book tour, now there’s an aspirational goal.

What’s your weirdest idea for a book you’ll never get to publish?

Well, if having a pig detective trying to find Aladdin’s lamp isn’t weird enough, I don’t know what is. Seriously, I think that any idea, regardless of how outlandish, may have the germ of a story in it somewhere. It may just need some nurturing and the occasional reality check before it ever becomes part of a coherent narrative.

The ex-husband’s trenchcoat and Zoe Ferraris’s Writing Life

Fiction—and lately in particular crime fiction—can take us deep into alien cultures, through the emotions of the characters who act as our guides, translators and social commentators. The more alien the culture, the bigger the challenge to a Western author. Zoe Ferraris took on Saudi Arabia, one of the most closed cultures in the world, and succeeded. Her first novel “Finding Nouf” gave readers the excitement of discovery and the fascination of educating ourselves about a place we know so little—despite its importance to our own lives. Ferraris lifted the veil on this repressed yet fascinating culture, through a mystery based around the disappearance of a young girl. Her detective, Nayir Sharqi, is a desert guide from Jeddah but, true to contemporary Arabia, almost none of the action goes on in the desert. Instead, he spends his time as a nervous interloper in the compounds of the rich and in restaurants where men and women are allowed the forbidden frisson of actually dining together. It’s great to know Zoe'll be continuing her series, because one of the things I took from “Finding Nouf” was a sense of the hidden depths of Saudi culture and family life, and a desire to know more. How did Ferraris do it? Here’s her explanation:

How long did it take you to get published?

Roughly ten years. It took a year to write the novel, then I spent years revising it while working on other projects and looking for an agent. Once a publisher bought the novel, it took two years for the book to hit the shelves. People tell me this is normal, but I never used to believe it. As far as I was concerned, I was waging a war against the demonic forces of evil to fulfill my destiny.

Would you recommend any books on writing?

I say pick up anything that inspires the hell out of you and makes you wish you’d written it. Find that thing no matter what it is: TV, radio, and your neighbor’s chit-chat. You’ll learn everything you need to know from paying attention to what you love.

What’s a typical writing day?

Wake up, go to the computer and write. It doesn’t matter what it is – new writing, editing, compiling ideas, as long as I do a little writing first thing in the morning, it’s like some kind of hoodoo-voodoo that seals my fate for the rest of the day. Then I go swimming, walk the dog, eat lunch…and am drawn back to my computer like Li Grand Zombie.

Plug your latest book. What’s it about? Why’s it so great?

My latest book, CITY OF VEILS, is coming out next spring. It’s a sequel to FINDING NOUF, which is a mystery set in Saudi Arabia. My protagonists return – Nayir, a devout Muslim who is looking for love in a country that makes it difficult for him to interact with women, and Katya, a female forensic scientist who struggles to solve crimes in a male-dominated profession. I’ve also introduced two new characters – a Saudi homicide investigator and an American woman whose husband disappears, leaving her stranded in Jeddah. This novel is faster-paced than the first one, and I got to write about things that fascinate me: the lingerie industry, men with multiple wives, and the largest sand desert in the world.

How much of what you do is:

a) formula dictated by the genre within which you write?

b) formula you developed yourself and stuck with?

c) as close to complete originality as it’s possible to get each time?

I guess it’s formula from the mystery genre. That’s the straight answer. Most things occur outside of the formula vs. originality question. Sitting down at the computer is about hounding out those things that really excite me, and facing up to my inconsistencies, and trying to figure out what my protagonist would really do if he was thrown into a sandstorm.

What’s your favorite sentence in all literature, and why?

Am I allowed more than one? Say, about twenty?

The first one that comes to mind, the one that always makes me choke up is the final sentence of Italo Calvino’s short story All At One Point. The story is about life at the beginning of the universe, when everything existed all at one point, and how cramped and frustrated we all were sharing an infinitesimally small point with the entire universe. But this wonderful woman, Mrs. Ph(i)Nk0, decides to make pasta for everyone – “she who in the midst of our closed petty world had been capable of a generous impulse, ‘Boys! The noodles I would make for you!’ a true outburst of general love, initiating at the same moment the concept of space and, properly speaking, space itself, and time, and universal gravitation…making possible billions and billions of suns, and of planets and fields of wheat…” Can you tell I’m Italian?

Who’s the greatest stylist currently writing?

I am scanning the bookshelf and discovering that all of my favorite stylists are now dead.

Who’s the greatest plotter currently writing?

Robert Ludlum…is still alive, yes? And I know George R.R. Martin isn’t dead yet. He’d better not be, he’s got another three books to write, and I’m still WAITING.

How much research is involved in each of your books?

Ten times as much as I ever need. I spend half my time researching. In fact, it takes a firm act of will to stop researching and get down to the business of telling a story.

Where’d you get the idea for your main character?

From my ex-husband, who took me to a jacket souq in Jeddah and insisted on buying a trench coat because he loved Columbo and wanted to be like Peter Falk and go out and solve mysteries. Later, my character developed from all the men I knew in Saudi who were looking for wives but couldn’t find them because they had such a hard time meeting women in a gender-segregated society.

Do you have a pain from childhood that compels you to write? If not, what does?

Yes. It’s nothing graphic, but my parents owned a cabin in the Rocky Mountains and every weekend of my childhood we would leave the comforts of civilization for this utterly isolated grotesquerie of a house. Pretending that electricity, telephones and grocery stores were inessential, everyone threw themselves into it but me. I didn’t like sharing space with bears and cougars, knowing that the closest doctor was about a twenty mile walk through the woods. My defining moment was, at seven years old, seeing the stars in a clear mountain sky and learning that each of those pinpoints of light was actually a distant sun, with possible planets around it, and that in that whole wide universe we knew of no other life. Billions of suns, and….it’s just us? I was horrified.

That same year, Star Wars came out, offering (to my child’s mind at least) the possibility that we weren’t alone, that in fact the universe was full of Wookies and droids. A few years ago I realized that my worst fears revolve around isolation, and that in all of the novels I’ve written, my protagonists face it down one way or another.

Of course, why I chose to become a writer when isolation bothers me so much is still a puzzle.

What’s the best idea for marketing a book you can do yourself?

After getting published, it turns out you’ll have two jobs: continuing to write, and marketing your book. Arrange your own book tour locally – at bookstores, libraries, community gatherings. Even doing something once a month can be a help.

What’s your experience with being translated?

It goes like this: foreign publisher buys the book, translates it, sends you a copy. You open the book, scratch your head, close it, appreciate the cover art, then put it on the shelf. Sometimes you pass the shelf and wonder if they changed whole swathes of text, and if you’ll ever find out.

Do you live entirely off your writing? How many books did you write before could make a living at it?

I make a living at it now. I was lucky that my first novel sold in a number of countries, and all the advances added up to a living wage.

How many books did you write before you were published?

I wrote two, plus a number of unfinished projects that just ground to a halt. However, the two I did finish both went through so many overhauls that it was almost as if I’d written ten novels.

What’s your weirdest idea for a book you’ll never get to publish?

I’m not sure I have anything that qualifies as officially weird, but the furthest back of the back-burner projects is a non-fiction book about the way soldiers talk. I have a whole stack of anecdotes, collected over the years, involving how creative and shocking and wonderful their use of English can be.

The Snow Queen of Crime: Monica Kristensen’s Writing Life

On a recent trip to Oslo, I lunched with my publisher there Hakan Haket and an astonishingly fascinating local crime writer named Monica Kristensen. Extraordinarily charismatic, she has a trove of stories unlike anything one tends to come across in typical book chats. A Norwegian with a doctorate in glaciology from Cambridge University, Monica has led polar expeditions to retrace the route of her countryman Roald Amundsen to the South Pole. Out on the ice, she’s eaten dog meat – “chewy” – and polar bear meat – “smelly” – out of necessity. She also forced her way into the extremely macho world of polar exploration and, as a tall, striking blonde, became one of the most well-known and controversial scientists in Scandinavia. Over lunch she entertained me with her latest research on the tragic trip to the South Pole of Capt. Robert Scott, one of the last untarnished heroes of the British Empire. At least, he is now--until Monica writes a book on him, which I’m quite sure would cause enormous controversy in Britain…Though I’m sworn to secrecy about what she’s dug up on him.

Before you Nordic crime fans rush out to find her books, note that her work is yet to be published in English. I’ve decided that I’ll include on this blog writers whose work isn’t available in English. I want readers to be able to compare the way writers live when they work in a “small” language like Norwegian, as opposed to English-language writers who have such a large natural readership. It's something that I find very interesting as I travel Europe, meeting other writers and talking about their lives. I should add that Hakan rates Monica’s crime novels (which are set on a small island above the Arctic Circle called Svalbard where Monica lives part of the year) as the best of the current crop of Nordic crime writers—and he knows good crime fiction (He publishes me in Norwegian, after all!) Sharp-eyed publishers looking for a wonderful discovery in the burgeoning Nordic crime subgenre ought to contact Monica’s agent Eva Haagerup at Leonhardt & Høier in Copenhagen (eva@leonhardt-hoier.dk).

How long did it take you to get published?

Since I am a well known person in Norway, I have never had any problems getting published. This may not be an advantage. Resistance is necessary to develop writing skills.

Would you recommend any books on writing?

Accomplishment in writing is a craft as well as a talent. You really do benefit from criticism as well as encouragement. However, there is no recipe, so my advice is to look for books that you feel will inspire. If pressed, I would recommend “Creating Unforgettable Characters” by Linda Seger

What’s a typical writing day?

My writing day is quite organized. I get up early (about six thirty) to spend some time with my seven year old daughter before school. We cycle there and I exercise when I get back home. Then I sit down at the desk and work till about three o’clock (including a brief lunch break). I stop around four and spend time with my daughter. If I feel like it, I work for an hour or two after six o’clock. I love writing, so I have to stop myself from working during the weekends. But I allow myself to read relevant material, do research or note down ideas in a little black book that I carry with me everywhere.

Plug your latest book. What’s it about? Why’s it so great?

My latest book is “Operation Fritham”, published in Norway in June this year.

A small group of war veterans is gathering on Svalbard to commemorate a tragic incident during the Second World War – Operation Fritham. Germans, Norwegians and British former soldiers are present. But tensions among the former enemies are nothing compared to the difficulties Knut Fjeld experiences when he discovers that a civilian, a murderer, has taken the identity of one of the old soldiers and hidden among the veterans.

I particularly like this book because I feel that I have been able to describe the claustrophobic atmosphere in northern Norway in 1941, during the first part of the war - when the Third Reich in secrecy prepared an invasion of the northern Soviet Union across the Norwegian and Finnish borders. Nearly two hundred thousand German and Austrian soldiers occupied the county of Sør-Varanger with a pre-war population of about ten thousand. In the middle of a cauldron of soldiers, spies of various nations, traitors and quislings, one decent country police officer is fighting a desperate battle to protect the innocent and reveal the identity of a cold blooded murderer. Fifty years on, Knut Fjeld finds his old files and continues his quest for justice.

How much of what you do is:

a) formula dictated by the genre within which you write?

b) formula you developed yourself and stuck with?

c) as close to complete originality as it’s possible to get each time?

I would say that I float freely when the writing is good. No gravity, just splendid views over a fantasy landscape. I hardly ever think formula. I must therefore choose alternative c).

However, I am aware of the requirements of the crime fiction genre and try to respect the expectations of my readers. Stretching the envelope of genre must not be felt as a disappointment for the reader.

What’s your favorite sentence in all literature, and why?

I do not have a favorite sentence, unless “Let there be light” from the Book of Genesis can count? There are so many brilliant descriptions and sentences, Ernest Hemingway, Ray Bradbury, Somerset Maugham, Anton Chekhov, Graham Greene … perhaps Jorge Luis Borges will do as an example - in the poem “The watcher”; “The door to suicide is open, but theologians assert that, in the subsequent shadows of the other kingdom, there will I be, waiting for myself.”

What’s the best descriptive image in all literature?

Two images spring instantly to mind: The book of Revelation in the New Testament and Dante’s Inferno. But Tolkien has many, as well as Herman Neville (Moby Dick) and Joseph Conrad (Heart of Darkness)

Who’s the greatest stylist currently writing?

I simply can’t choose. And I feel that it would be a bit unfair, since I mainly read thrillers and crime fiction. But I will try anyway: Doris Lessing. She writes with confidence and passion.

Who’s the greatest plotter currently writing?

Again there are so many, but my favorite is John Le Carré. I would love to meet him.

How much research is involved in each of your books?

I do a lot of research for all my books, even if I am now writing crime fiction from Svalbard – and I have lived there for seven years. But I do like to be exact and correct in my writing. This is perhaps due to my background as a scientist.

Where’d you get the idea for your main character?

My main character, Knut Fjeld, is a man that will eventually (in book seven of a series of twelve books) become the head of the police force on Svalbard - the Sysselmann. This position is also the same as Governor of the Norwegian high Arctic, directly placed under the Norwegian King.

I am writing about police work and murders most gruesome committed close to the North Pole, in the world’s northernmost communities, occupied mainly by coal miners, scientists, tourists and adventurers.

Do you have a pain from childhood that compels you to write? If not, what does?

There is pain in everyone’s childhood – as well as in mine. But it is the joy and inspirations of childhood that inspires me to write. I loved reading and was encouraged to write my own stories from a very early age - by my parents, teachers and the librarian in the small town I grew up in.

What’s the best idea for marketing a book you can do yourself?

I am appallingly bad at marketing; don’t know the first thing about it. So it would seem that the best I have done so far is to get to know an author named Matt Rees and get myself interviewed on his web site.

What’s your experience with being translated?

Translations into the Scandinavian languages do not count, since they are very similar to Norwegian (except Icelandic). But I have difficulties with my own texts being translated into English. Since I have lived in UK for a total of seven years, I have developed an English persona, and it is very different from the Norwegian one. I would not tell a story the same way in English. What works best is to shut my eyes and let the translator get on with it.

Do you live entirely off your writing? How many books did you write before could

make a living at it?

I do not live entirely off my writing. I also work as a glaciologist and climate scientist. I find that the two professions go well together. I tend to become restless after a period of writing, and the strict logic of science is refreshing after the exhilaration of creativity.

How many books did you write before you were published?

I was published with my first book, but I had been writing for about thirty years by then (I made my first poem when I was five). However, I must stress that I do not consider resistance from a publisher to be a bad thing. If I had struggled more to get it published, maybe my first book would have been different, perhaps better.

In all, I have written six books, and I am currently working on number seven (a documentary about a mining accident in the Arctic).

What’s the strangest thing that happened to you on a book tour?

I am in two minds about book tours; I love to get in contact with readers, but get very tired of talking about myself. Nothing very strange has happened to me on book tours, but I have been mistaken for an employee in a book store when I was there to sign my books. I actually liked that, being for once so anonymous.

What’s your weirdest idea for a book you’ll never get to publish?

I regard creating new ideas as one of my strong sides. I see stories in my surroundings most days. My type of creativity feels like a well of storytelling inside my head. I love to create riddles, make people wonder: “Now how could that have happened? And what happens next?”

In answer to your question: No idea is too weird for me to write about. After all, when I was young, I read a lot of science fiction short stories – and because of the nature of this literature, these stories had to be instantly good to capture skeptical readers immediately.

Poetry from the ‘driest’ book of the Bible: Yakov Azriel’s Writing Life

A few years ago I was at a literary conference near Tel Aviv. I found an eclectic mix of writers on the panel with me. I’m a crime writer. You wouldn’t expect me to be paired with a writer of poetry who takes his inspiration from the stories of the Bible. But as Yakov Azriel read his poetry, I sat beside him feeling that no contemporary poems had ever touched me as deeply. They’re full of the knowledge of the Bible the Brooklyn-born poet garnered during his studies at Israeli yeshivas and his four decades living here. There’s something else though: they bring to life the hills and desert around Jerusalem. To an outsider, it can often seem strange that so many people are attached to a place that’s stark and rather ugly and certainly not a nurturing environment for sustaining human life. With Yakov’s poems I think you’ll find a sense of what the place means. Here’s his interview, followed by a wonderful poem from his newest book.

How long did it take you to get published?

It took a few years of submitting my first manuscript of poetry to different publishers until my first book of poetry was published.

What’s a typical writing day?

I make a living by working as a teacher, so during the daytime I do not have the opportunity to write. I usually try to write in the evenings and at night (especially at night); I try to write one new poem a week.

Plug your latest book. What’s it about? Why’s it so great?

My latest book is entitled Beads for the Messiah's Bride: Poems on Leviticus, and it was published in June by Time Being Books (a literary press specializing in poetry). Like my two previous books of poetry (Threads From A Coat Of Many Colors: Poems On Genesis and In The Shadow Of A Burning Bush: Poems On Exodus, each poem in the book begins with a Biblical verse and the book is structured as a running commentary, starting with chapter 1, verse 1 and ending with the last Biblical chapter.

This book was challenging for several reasons. My first book focused on the different characters in Genesis, and I especially tried to focus on the gaps in the Biblical narrative (for example, who was Abraham's mother?) or to give a voice to figures who are silent in the Biblical text (such as Dinah, or Joseph's wife Asenat). In the poems on Exodus, the many events in the Biblical narrative itself (the enslavement in Egypt, the Ten Plagues, Passover, the splitting of the Red Sea, etc.) readily lent themselves to poetry.

In contrast, the Book of Leviticus is considered to be "drier," without the drama and large cast of characters of the first two books of the Bible. One device I used in order to grapple with this difficulty was a conscious effort to fuse the English literary tradition with the Jewish-Hebrew heritage. For example, the first chapters of Leviticus deal with sacrifices; I decided to write a Petrarchan sonnet for each sacrifice, a sonnet that is a prayer, modeled after the "Holy Sonnets" of John Donne. In the end, one book reviewer felt that this book was the most powerful of my three published books (eventually, we will be publishing five volumes of poetry, one for each of the Five Books of Moses).

How much of what you do is:

a) formula dictated by the genre within which you write?

b) formula you developed yourself and stuck with?

c) as close to complete originality as it’s possible to get each time?

I write poetry in all forms: mainly free verse (like most 21st century poets), but also formal, metric poems — sonnets, sestinas, villanelles, ballads, etc. Each poem has a life of its own, and it is the poet's duty to help each poem find its own voice. Just as a sculptor has to liberate the statue that is hidden in a block of marble, so the poet has to liberate the poem hidden on the empty page and grant it breath.

As I said, all my poems are based on the Bible. The Biblical verse is like an iceberg, with 90 % of its meaning under the surface; my job is to try to get under the surface.

T.S. Eliot said that there is little good religious poetry being written today because the religious poet tends to write what he thinks he ought to feel instead of what he really feels. All good poetry must be sincere. So part of my task as a poet is to be sincere, as much as possible.

What’s your favorite sentence in all literature, and why?

This is a very difficult question to answer! One sentence that really resonates for me in English literature is when Hamlet describes his father to Horatio in Act I, Scene II, and tells him that "He was a man." What a wonderful example of praise, love and understatement in four simple words.

In Biblical literature, one sentence that that I find very powerful occurs right after the scene in which the prophet Nathan tells King David the parable of the poor man's lamb (First Samuel, Chapter 12) and King David, incensed, says that this man deserves to die; after Nathan exclaims, "You are the man," David does not argue but admits, "I have sinned."

What’s the best descriptive image in all literature?

Again this is very difficult to answer, but I think that Dicken's description in Little Dorrit of the banquet scene in Rome in which Mr. Dorrit relives the past he has been trying so hard to conceal, and calls out loud to Amy, speaking about the turnkey and his imprisonment in the Marshalsea prison — this is certainly one of them.

How much research is involved in each of your books?

I have been "researching" my books all my life.

Where do you get your ideas?

This is a very good question. Often in the middle of the night an idea comes; I have to write it down, and the following evening, I work on it.

Do you have a pain from childhood that compels you to write? If not, what does?

No, I do not think that it stems from a childhood pain. Why do I write? Ask me why I breathe. The great German poet Rilke said that no one should write poetry unless he would have to die if it were denied him to write. Perhaps this is too strong (for me at least) but I cannot imagine a life for myself without writing.

What’s your experience with being translated?

I have translated several of my poems into Hebrew. However, you could perhaps claim that all of poetry is a kind of translation of dream language into waking language.

What’s your weirdest idea for a book you’ll never get to publish?

To write it in Yiddish.

And now, some poetry: from Beads for the Messiah's Bride: Poems on Leviticus (Time Being Books, 2009)

THE SCAPEGOAT

“And Aaron shall place both his hands on the head of the scapegoat and confess upon it all the sins of the Children of Israel and all their crimes, whatever their transgressions; they will be put on the head of the scapegoat, which will be sent off to the desert in the hands of the executioner.” (Leviticus 16:21)

Bright crimson ribbons tied between his horns,

A clanking, clinking bell around his neck,

His back bedecked with ornaments of silk —

Why did the priest place hands upon my head,

Then trembling shout a list of sins and crimes?

I bet I know: they want to crown me king,

A wise and noble king who never dies.

An orchestra of Levites play their flutes,

Their golden harps, their ten-stringed lutes, their drums,

Their silver trumpets as he is taken out —

Why I alone am sent to Azazel?

And who or what the hell is ‘Azazel’?

I bet I know: they think I am an angel,

A pure, immortal angel full of grace.

Out of the Temple precinct packed with crowds,

And out the narrow lanes of Jerusalem,

And out Damascus Gate, toward desert cliffs —

Why am I brought here to this mountain peak?

Why rip the crimson ribbons from my horns?

I bet I know: they wish to worship me,

I bet I —