Matt Rees's Blog - Posts Tagged "writing-tips"

Writing Tip #93: Walking and plotting

Readers like to ask writers “Where do you get your ideas?” It’s such a common question at book readings that I’ve noticed writers (on blogs) making fun of people who ask it. Yet it’s rather silly to ridicule someone for asking a question most writers can’t answer themselves.

Readers like to ask writers “Where do you get your ideas?” It’s such a common question at book readings that I’ve noticed writers (on blogs) making fun of people who ask it. Yet it’s rather silly to ridicule someone for asking a question most writers can’t answer themselves.So here’s my answer: I get my best ideas by walking.

Just lately I’ve been plotting my next book, which is going to be a thriller set in Iraq and New York. I’ve done a good deal of thinking about it in my office, standing in front of my computer or slouched in my bean bag. But when I’m in front of the computer, I find myself thinking about what to write for this blog. And on the bean bag I get distracted by the little white polystyrene balls which seem endlessly to leak out of it onto my Iranian kilim.

The best ideas for this new novel have come to me as I walk home from the gym. It’s not because I’m walking through the prettiest part of town. I walk along a busy dual-carriageway linking two other noisy, busy roads. I sweat like a pig, too – I remind you that I live in Jerusalem, which is a mountainous desert town.

But all the way I’m chattering into my digital voice recorder, setting down my ideas. The reason is simple: relaxation and lack of distraction. I have nothing else to do but walk. Nowhere to go but where I’m going. Nothing to see but fast-moving traffic and a deserted sand lot. My mind is free to be creative, because it’s unhindered by anything else. (I’m quite capable of walking and doing something else at the same time, fortunately.)

In my meditation classes, I’ve sometimes practiced a walking meditation. If you pay attention to each step, the way your foot falls, you’ll soon find your mind entirely clear of any distraction. The same thing is happening on my way home from the gym.

Read the rest of this post on my blog The Man of Twists and Turns.

Published on June 30, 2011 09:18

•

Tags:

ideas, iraq, meditation, new-york, plots, thriller, walking-meditation, writing, writing-tips

Writing Tip #93: Real historical charcters in a novel

I dislike the law and I have little interest in ethics. So here’s a post about the ethics and legality of using real characters in fiction, as I do in my latest novel MOZART’S LAST ARIA. It’s the one time I’ll bother to write about either subject.

I dislike the law and I have little interest in ethics. So here’s a post about the ethics and legality of using real characters in fiction, as I do in my latest novel MOZART’S LAST ARIA. It’s the one time I’ll bother to write about either subject.In a Fringe Magazine review of MOZART’S LAST ARIA, reviewer Scott Wilson notes how much he enjoyed the book. (“This story was extremely well-written and up there with many other great whodunit books. The narrative is both beautiful and historically accurate, as are many other elements of this crime novel. It is obvious that Rees did some pretty extensive research in developing the foundation for this book. I found the pages of the book turning themselves with the ripping read and sense of urgency that the author created with the plot.”)

Thanks, Scott. Reviews don’t get much better than that.

But my novel also touched off another thought in Scott that’s worth looking at in more depth. Here’s what he wrote:

Mozart’s Last Aria is one of those books that amazes me. I don’t know how you can write a fictional novel based on a real person without being sued for slander or defamation etc etc. I mean the concept of using a real, historical figure and adding elements of fiction to make an interesting story has some merit to it and in some cases, such as this book, it makes a great read. But I just don’t understand how you can get sued for plagiarism by using someone else’s song lyrics or stories, but to take a person’s life and write what every the hell you want about it is okay??? Don’t imagine being able to write a novel based on Han Solo or Sherlock Holmes and being able to make millions without it being an issue to anyone else? I’m going to have to do some research into the legalities of writing a fictional novel based on real people for my own curiosity now.

There are a few issues raised in this paragraph. The first is: what’s legal? My understanding, in very blunt terms is: as long as the person is dead, they can be fictionalized.

That’s how you come to have real Hollywood actor Sal Mineo as a gigolo in James Ellroy’s novels. Or Lee Harvey Oswald in Don de Lillo’s “Libra.” Or Virginia Woolf in “The Hours.” If they were still alive, they might’ve sued. Or Mineo would’ve had the mob knee-cap Ellroy, Oswald might’ve assassinated de Lillo, and Woolf may have attempted to beat Michael Cunningham to death with the enormous false nose Nicole Kidman wore in the film version.

But they didn’t. Because they’re dead. Like Mozart. (In fact, my novel is about what really caused his death, so that’d have to be the point.)

So let’s get to the ethics. A fairly silly “outraged” blog on The Guardian website a couple of years ago suggested that “increased” use of real dead famous people by novelists was an ethical issue and that it was the result of the decline of privacy and private space in the age of Twitter, Facebook and My Space (thus revealing that the blogger wasn’t really up on the latest developments with My Space, which has been called the “abandoned theme park of the internet” for years now.) By going inside the heads of famous dead people, novelists reveal themselves to care not a jot for privacy, he writes.

Actually, I agree that the privacy of dead people is an issue of little importance, in a world riven by war, rapine, and investment bankers. There are bigger fish to fry.

Read the rest of this post on my blog The Man of Twists and Turns.

Published on July 07, 2011 04:46

•

Tags:

crime-fiction, han-solo, historical-fiction, mozart-s-last-aria, sherlock-holmes, the-fringe-magazine, the-guardian, writing, writing-tips

Writing crime fiction: Finding the writer to inspire your own creativity

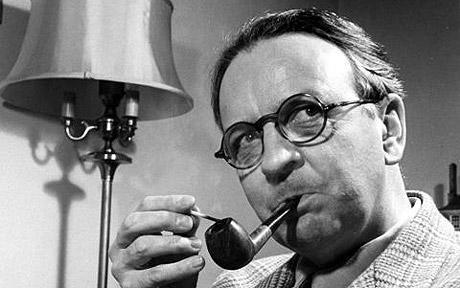

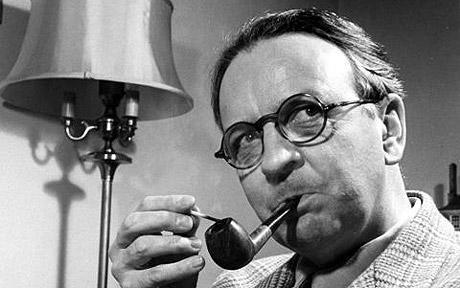

Writers should study an author whose work sparks them creatively. Mine is Raymond Chandler

Whenever I start writing a new book, I re-read some Raymond Chandler. The books I write don't turn out much like Chandler in the end. But I repeat this process because his writing sparks me creatively. Every writer should have an author whose work does this for him. Here's how it works for me.

Not long ago I picked The Long Goodbye off the shelf, because it’s my favorite. From the very first page, where Marlowe finds Terry Lennox falling drunk out of a Rolls Royce Silver Wraith in front of a club called The Dancers, I find myself hooked once again:

“The girl gave him a look which ought to have stuck at least four inches out of his back. It didn’t bother him enough to give him the shakes.”

One day I may write something that good. While I'm waiting, I recline with Chandler and my little orange notebook, reading one of his concrete images -- and an image of my own springs into my head. The image that comes to me is nothing like Chandler's, but I know it appeared because I was reading Chandler. It doesn't happen with other writers. Not even Hammett.

There are characteristics of a work of art that work on us indefinably and subconciously. Take Mozart, about whom I wrote my historical thriller Mozart's Last Aria. Numerous studies have shown that his music can effect the brain. It helps ADD kids concentrate in class. It prevents epileptic seizures. But the same thing's untrue of, say, Beethoven. Some quality in Mozart's music has a unique effect on the brain.

Every one of us has a writer out there who can provide the Mozartean music to our creativity. For me it's Chandler. You have to find yours by trial and error.

Along with Hammett, Chandler did everything for American literature that people always assume Hemingway did: made things simple, direct, tough and stark. But unlike Hemingway (and like Hammett), Chandler had the gruff sense of humor of a man who didn’t buy into the system. He wasn’t a Communist like Hammett, but he’d lived in England and been in the Canadian airforce, and he'd been around a while before he started writing.

That’s why he wrote crime novels. It’s an outsider’s genre, the writing venue of a man or woman who sees through things and yet remains positive enough to bother putting pen to paper.

Chandler, like Marlowe, seems to have “felt as out of place as a cocktail onion on a banana split.” Frequently, so have I, when I’ve been among the corporate or the gilded of this world –– and I have spent many an uncomfortable day, month or year in those scurrilous circles. That, in fact, may be why I’m a writer. Certainly it helps me cope with the weird status a writer holds today, threatened and undervalued, and yet cherished (though not always enough for someone to buy your book and pay for your

kids to go to college.)

Which writer will you find to do this for you? Who's going to worm his/her way into your brain and open the creative stream?

Related articles across the web

Authors' Favorite First Lines of Books

Authors' Favorite First Lines of Books

Ellroy and Hammett: The Tory and the Communist

Ellroy and Hammett: The Tory and the Communist

The myth of the drinking writer

The myth of the drinking writer

Raymond Chandler: The Master of Nasty

Raymond Chandler: The Master of Nasty

Who is the greatest American novelist? 1: Saul Bellow v Raymond Chandler

Who is the greatest American novelist? 1: Saul Bellow v Raymond Chandler

Whenever I start writing a new book, I re-read some Raymond Chandler. The books I write don't turn out much like Chandler in the end. But I repeat this process because his writing sparks me creatively. Every writer should have an author whose work does this for him. Here's how it works for me.

Not long ago I picked The Long Goodbye off the shelf, because it’s my favorite. From the very first page, where Marlowe finds Terry Lennox falling drunk out of a Rolls Royce Silver Wraith in front of a club called The Dancers, I find myself hooked once again:

“The girl gave him a look which ought to have stuck at least four inches out of his back. It didn’t bother him enough to give him the shakes.”

One day I may write something that good. While I'm waiting, I recline with Chandler and my little orange notebook, reading one of his concrete images -- and an image of my own springs into my head. The image that comes to me is nothing like Chandler's, but I know it appeared because I was reading Chandler. It doesn't happen with other writers. Not even Hammett.

There are characteristics of a work of art that work on us indefinably and subconciously. Take Mozart, about whom I wrote my historical thriller Mozart's Last Aria. Numerous studies have shown that his music can effect the brain. It helps ADD kids concentrate in class. It prevents epileptic seizures. But the same thing's untrue of, say, Beethoven. Some quality in Mozart's music has a unique effect on the brain.

Every one of us has a writer out there who can provide the Mozartean music to our creativity. For me it's Chandler. You have to find yours by trial and error.

Along with Hammett, Chandler did everything for American literature that people always assume Hemingway did: made things simple, direct, tough and stark. But unlike Hemingway (and like Hammett), Chandler had the gruff sense of humor of a man who didn’t buy into the system. He wasn’t a Communist like Hammett, but he’d lived in England and been in the Canadian airforce, and he'd been around a while before he started writing.

That’s why he wrote crime novels. It’s an outsider’s genre, the writing venue of a man or woman who sees through things and yet remains positive enough to bother putting pen to paper.

Chandler, like Marlowe, seems to have “felt as out of place as a cocktail onion on a banana split.” Frequently, so have I, when I’ve been among the corporate or the gilded of this world –– and I have spent many an uncomfortable day, month or year in those scurrilous circles. That, in fact, may be why I’m a writer. Certainly it helps me cope with the weird status a writer holds today, threatened and undervalued, and yet cherished (though not always enough for someone to buy your book and pay for your

kids to go to college.)

Which writer will you find to do this for you? Who's going to worm his/her way into your brain and open the creative stream?

Related articles across the web

Authors' Favorite First Lines of Books

Authors' Favorite First Lines of Books  Ellroy and Hammett: The Tory and the Communist

Ellroy and Hammett: The Tory and the Communist  The myth of the drinking writer

The myth of the drinking writer  Raymond Chandler: The Master of Nasty

Raymond Chandler: The Master of Nasty  Who is the greatest American novelist? 1: Saul Bellow v Raymond Chandler

Who is the greatest American novelist? 1: Saul Bellow v Raymond Chandler

Published on February 05, 2014 04:35

•

Tags:

crime-fiction, raymond-chandler, writing, writing-tips

Writing crime fiction: Don't use the magic hacker

The computer 'hacker' character undermines the credibility of many thrillers

The use of a hacker character in Swedish writer Stieg Larsson's megaseller The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo

The use of a hacker character in Swedish writer Stieg Larsson's megaseller The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo made me want to throw knives like the Swedish Chef on The Muppet Show. To explain why, let's look at the role the "hacker" character has taken in recent crime fiction (and in movie thrillers.)

made me want to throw knives like the Swedish Chef on The Muppet Show. To explain why, let's look at the role the "hacker" character has taken in recent crime fiction (and in movie thrillers.)

In Dragon Tattoo the eponymous heroine is the now generic thriller/mystery character: the Internet hacker genius. Whenever Larsson needs to inject some new information or to unravel a tricky plot point, his hacker opens up her laptop and links into www.secretgovernmentinformation.gov, the well-known (to fiction writers) site where intelligence networks store material they want to be sure is available only to fictional hacker geniuses (and by proxy to thriller writers).

Hackers can do this kind of thing. But thriller writers don't take the time to learn enough about cybercrime to make the manner in which hackers operate credible. It all takes place by magic. Dragon Tattoo isn’t the worst offender on this score. Just the biggest seller.

Computers and hackers are a necessary part of today's criminal world and therefore of crime fiction. That's why I'm currently taking a course in cybercrime and cybersecurity. I want to be sure any computer crime in my novels is handled credibly. I've learned that any hacking you make up off the top of your head will be a lot less scary than what real hackers (whether individuals, crime syndicates, or governments) are up to.

If you don't believe me, watch this:

In my previous novels the only time the Internet comes up is in A Grave in Gaza when the granddaughter of my Palestinian sleuth Omar Yussef sets up a website for him in her attempt to make him seem more professional. The Palestine Agency for Detection, as she calls her site, is merely embarrassing to Omar. No plot-point-shifting Houdini act there.

I'm sensitive to this question of hackers in thrillers, because I've been living in the Middle East for almost two decades. How does that follow? Here's how:

The computer hacker has taken over from the Israeli Mossad as the thriller writer’s cure-all. In the old days, if there was something your main character couldn’t figure out, all he had to do was get in touch with the nearest Mossad agent, who’d be sure to know all the secrets in the world and was happy to pass them on with a few dark words about never forgetting the Holocaust and a cheerful “Shalom.”

As someone who presently lives in Israel, I can tell you the Mossad doesn’t operate that way. Neither does the Internet. So write credibly about the work of hackers and those who fight them. That'll make your work seem much less like that of a ... hack.

Related articles across the web

The Girl With the Dragon Tattoo: new author signed up for fourth book

The Girl With the Dragon Tattoo: new author signed up for fourth book

Sequel announced to Stieg Larsson's Girl With the Dragon Tattoo trilogy

Sequel announced to Stieg Larsson's Girl With the Dragon Tattoo trilogy

New author to continue 'The Girl With The Dragon Tattoo' series

New author to continue 'The Girl With The Dragon Tattoo' series

The use of a hacker character in Swedish writer Stieg Larsson's megaseller The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo

The use of a hacker character in Swedish writer Stieg Larsson's megaseller The Girl with the Dragon TattooIn Dragon Tattoo the eponymous heroine is the now generic thriller/mystery character: the Internet hacker genius. Whenever Larsson needs to inject some new information or to unravel a tricky plot point, his hacker opens up her laptop and links into www.secretgovernmentinformation.gov, the well-known (to fiction writers) site where intelligence networks store material they want to be sure is available only to fictional hacker geniuses (and by proxy to thriller writers).

Hackers can do this kind of thing. But thriller writers don't take the time to learn enough about cybercrime to make the manner in which hackers operate credible. It all takes place by magic. Dragon Tattoo isn’t the worst offender on this score. Just the biggest seller.

Computers and hackers are a necessary part of today's criminal world and therefore of crime fiction. That's why I'm currently taking a course in cybercrime and cybersecurity. I want to be sure any computer crime in my novels is handled credibly. I've learned that any hacking you make up off the top of your head will be a lot less scary than what real hackers (whether individuals, crime syndicates, or governments) are up to.

If you don't believe me, watch this:

In my previous novels the only time the Internet comes up is in A Grave in Gaza when the granddaughter of my Palestinian sleuth Omar Yussef sets up a website for him in her attempt to make him seem more professional. The Palestine Agency for Detection, as she calls her site, is merely embarrassing to Omar. No plot-point-shifting Houdini act there.

I'm sensitive to this question of hackers in thrillers, because I've been living in the Middle East for almost two decades. How does that follow? Here's how:

The computer hacker has taken over from the Israeli Mossad as the thriller writer’s cure-all. In the old days, if there was something your main character couldn’t figure out, all he had to do was get in touch with the nearest Mossad agent, who’d be sure to know all the secrets in the world and was happy to pass them on with a few dark words about never forgetting the Holocaust and a cheerful “Shalom.”

As someone who presently lives in Israel, I can tell you the Mossad doesn’t operate that way. Neither does the Internet. So write credibly about the work of hackers and those who fight them. That'll make your work seem much less like that of a ... hack.

Related articles across the web

The Girl With the Dragon Tattoo: new author signed up for fourth book

The Girl With the Dragon Tattoo: new author signed up for fourth book  Sequel announced to Stieg Larsson's Girl With the Dragon Tattoo trilogy

Sequel announced to Stieg Larsson's Girl With the Dragon Tattoo trilogy  New author to continue 'The Girl With The Dragon Tattoo' series

New author to continue 'The Girl With The Dragon Tattoo' series

Published on February 06, 2014 04:11

•

Tags:

computer-hackers, crime-fiction, thrillers, writing, writing-tips

Writing crime fiction: Readers want someone else's fear, not their own

Writers must find the fears that titillate, rather than terrify.

Americans fear public speaking and clowns. (Check out the polls. It’s true.) Surprisingly, they don’t fear being murdered by a psychopath or caught up in a case of mistaken identity which leads to them be pursued by the FBI.

Americans fear public speaking and clowns. (Check out the polls. It’s true.) Surprisingly, they don’t fear being murdered by a psychopath or caught up in a case of mistaken identity which leads to them be pursued by the FBI.

Surprisingly, that is, if you read thrillers.

Crime novels don’t hinge on the fears people confront in everyday life. But six of the current New York Times Top 10 bestseller list are thrillers. Why do so many people read crime novels, if not to experience real fear? You’d better have an answer figured out if you’re going to write a thriller that hits not on people’s true horrors, but on the fears they like to be teased with in literary form.

We can sum up the genre’s popularity this way: our innate conservatism enjoys seeing order disturbed (by murder) and then restored (by nabbing the bad guy.)

Hence the popularity of Scandinavian detective novels. Where else is there such order? The disturbance is consequently great. But we never fear that Wallander or Hole will fail to restore balance, and everyone can head for the sauna with a sense of security.

To prove this, look also at James Ellroy. He has said that his novels are too dark and gritty to have huge sales. His masterpiece American Tabloid has sold less than 400,000 copies. That’s a hell of a lot, of course. But many a lesser thriller writer shifts millions of copies of each book.

Ellroy’s novels are too close to our real fears. I don’t mean clowns. He undercuts the comforting realities of American history. When you read American Tabloid, you can’t help but think that if JFK was such a weak-willed, corrupt poon-hound, maybe all the other myths and foundations of our society are delusions too. There’s no coming back from that. So the sales stay low.

People like to maintain a distinction between fiction and reality.

They recognize the difference between fictional fear and real fear. The shock of 9/11 was, as many witnesses said, that it was “like a Hollywood disaster movie.” Like a fiction. Too much to take in as real. Which is why there was such a backlash against perceived perpetrators. They had killed a lot of people, sure. But they also had shattered our belief in the distinction between reality and nightmare.

Next we’ll try to figure out how to find the fears that titillate, rather than truly terrify. Let me know what fits the bill for you.

Related articles across the web

This Changes Everything: Ellroy and Mallon on the Assassination of JFK

This Changes Everything: Ellroy and Mallon on the Assassination of JFK

James Ellroy and David Peace: History Repeats Itself

James Ellroy and David Peace: History Repeats Itself

Evil Clown Costumes a Cause of Coulrophobia

Evil Clown Costumes a Cause of Coulrophobia

No: 739 The Troubled Man by Henning Mankell

No: 739 The Troubled Man by Henning Mankell

Americans fear public speaking and clowns. (Check out the polls. It’s true.) Surprisingly, they don’t fear being murdered by a psychopath or caught up in a case of mistaken identity which leads to them be pursued by the FBI.

Americans fear public speaking and clowns. (Check out the polls. It’s true.) Surprisingly, they don’t fear being murdered by a psychopath or caught up in a case of mistaken identity which leads to them be pursued by the FBI.Surprisingly, that is, if you read thrillers.

Crime novels don’t hinge on the fears people confront in everyday life. But six of the current New York Times Top 10 bestseller list are thrillers. Why do so many people read crime novels, if not to experience real fear? You’d better have an answer figured out if you’re going to write a thriller that hits not on people’s true horrors, but on the fears they like to be teased with in literary form.

We can sum up the genre’s popularity this way: our innate conservatism enjoys seeing order disturbed (by murder) and then restored (by nabbing the bad guy.)

Hence the popularity of Scandinavian detective novels. Where else is there such order? The disturbance is consequently great. But we never fear that Wallander or Hole will fail to restore balance, and everyone can head for the sauna with a sense of security.

To prove this, look also at James Ellroy. He has said that his novels are too dark and gritty to have huge sales. His masterpiece American Tabloid has sold less than 400,000 copies. That’s a hell of a lot, of course. But many a lesser thriller writer shifts millions of copies of each book.

Ellroy’s novels are too close to our real fears. I don’t mean clowns. He undercuts the comforting realities of American history. When you read American Tabloid, you can’t help but think that if JFK was such a weak-willed, corrupt poon-hound, maybe all the other myths and foundations of our society are delusions too. There’s no coming back from that. So the sales stay low.

People like to maintain a distinction between fiction and reality.

They recognize the difference between fictional fear and real fear. The shock of 9/11 was, as many witnesses said, that it was “like a Hollywood disaster movie.” Like a fiction. Too much to take in as real. Which is why there was such a backlash against perceived perpetrators. They had killed a lot of people, sure. But they also had shattered our belief in the distinction between reality and nightmare.

Next we’ll try to figure out how to find the fears that titillate, rather than truly terrify. Let me know what fits the bill for you.

Related articles across the web

This Changes Everything: Ellroy and Mallon on the Assassination of JFK

This Changes Everything: Ellroy and Mallon on the Assassination of JFK  James Ellroy and David Peace: History Repeats Itself

James Ellroy and David Peace: History Repeats Itself  Evil Clown Costumes a Cause of Coulrophobia

Evil Clown Costumes a Cause of Coulrophobia  No: 739 The Troubled Man by Henning Mankell

No: 739 The Troubled Man by Henning Mankell

Published on February 11, 2014 03:07

•

Tags:

crime-fiction, james-ellroy, scandinavian-crime-fiction, thrillers, writing, writing-tips

Writing crime fiction: You need a daily routine for your writing

Crime writers need to work every day at the same time

Writing doesn't begin at the moment you set finger to keyboard. It starts...when it starts. To write a crime novel you need to have a routine and stick to it. That means working at the same time every day.

Part of writer's block is the feeling that you could be doing something else right now. If you don't insist on writing every work day, you'll be blocked because your insecurities will push you to do something else. If you don't write at the same time every day, your insecurities will suggest a trip to the coffee shop or a tv show on the basis that you'll find time to write later.

But you shouldn't be, and you won't. The great French novelist Flaubert said, "Be regular and orderly in life, so as to be violent and original in your work."

Whenever you hear a top crime writer talk, someone always asks them about their routine. None of them ever say, I write when I feel inspired.

James Patterson tells us he gets up at 5.30 a.m. to work. (I get up at 5.30, but that's because my two-year-old daughter is demanding pancakes.)

David Liss used to start work at 4 a.m. He happened to be writing two books at the time.

Most writers get going by 9 a.m. and roll until early afternoon. Elmore Leonard used to keep himself hungry by eating a handful of nuts for lunch and writing until 6 p.m.

Certainly the morning seems to be the most popular and productive time for writers. The only writer who seems to choose the evening is George Pelecanos. Zip through this video to 23.35 to hear him talk about this:

Michael Connolly wrote his first novel at night, because he was a newspaper reporter by day and had made a deal with his wife that they wouldn't go out four nights a week so he could write.

Larry McMurtry said that a writer should work every day to maintain momentum. He added that you should stop before you felt played out and exhausted, so that you'd have the energy and appetite to get back at it the next day.

For me, the routine begins every day after I've taken my son to school. By about 8 a.m. I'm working. I keep at it until somewhere between 11 and 2. The end of the day depends on the stage of the novel. If I'm spewing out the first draft, I'll keep going because I'm desperate to get everything down. Once I'm refining the manuscript, I finish a little earlier in the day, because close-reading is relatively exhausting.

But the start of the day is not negotiable for me. It should be that way for you too.

Related articles across the web

Literary crime fiction

Literary crime fiction

Elmore Leonard, crime novelist, dies

Elmore Leonard, crime novelist, dies

Music to murder to: crime writers on their killer soundtracks

Music to murder to: crime writers on their killer soundtracks

Writing doesn't begin at the moment you set finger to keyboard. It starts...when it starts. To write a crime novel you need to have a routine and stick to it. That means working at the same time every day.

Part of writer's block is the feeling that you could be doing something else right now. If you don't insist on writing every work day, you'll be blocked because your insecurities will push you to do something else. If you don't write at the same time every day, your insecurities will suggest a trip to the coffee shop or a tv show on the basis that you'll find time to write later.

But you shouldn't be, and you won't. The great French novelist Flaubert said, "Be regular and orderly in life, so as to be violent and original in your work."

Whenever you hear a top crime writer talk, someone always asks them about their routine. None of them ever say, I write when I feel inspired.

James Patterson tells us he gets up at 5.30 a.m. to work. (I get up at 5.30, but that's because my two-year-old daughter is demanding pancakes.)

David Liss used to start work at 4 a.m. He happened to be writing two books at the time.

Most writers get going by 9 a.m. and roll until early afternoon. Elmore Leonard used to keep himself hungry by eating a handful of nuts for lunch and writing until 6 p.m.

Certainly the morning seems to be the most popular and productive time for writers. The only writer who seems to choose the evening is George Pelecanos. Zip through this video to 23.35 to hear him talk about this:

Michael Connolly wrote his first novel at night, because he was a newspaper reporter by day and had made a deal with his wife that they wouldn't go out four nights a week so he could write.

Larry McMurtry said that a writer should work every day to maintain momentum. He added that you should stop before you felt played out and exhausted, so that you'd have the energy and appetite to get back at it the next day.

For me, the routine begins every day after I've taken my son to school. By about 8 a.m. I'm working. I keep at it until somewhere between 11 and 2. The end of the day depends on the stage of the novel. If I'm spewing out the first draft, I'll keep going because I'm desperate to get everything down. Once I'm refining the manuscript, I finish a little earlier in the day, because close-reading is relatively exhausting.

But the start of the day is not negotiable for me. It should be that way for you too.

Related articles across the web

Literary crime fiction

Literary crime fiction  Elmore Leonard, crime novelist, dies

Elmore Leonard, crime novelist, dies  Music to murder to: crime writers on their killer soundtracks

Music to murder to: crime writers on their killer soundtracks

Published on February 12, 2014 04:14

•

Tags:

crime-fiction, elmore-leonard, george-pelecanos, james-patterson, thrillers, writing, writing-routines, writing-tips

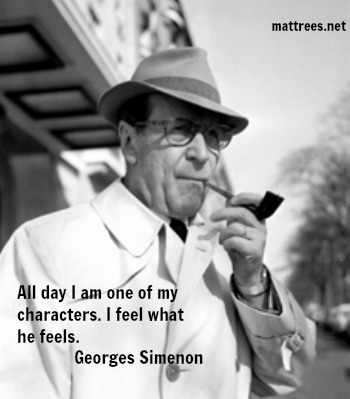

Writing crime fiction: Getting into character

A writer must feel what his characters feel to convey the emotion and sensation

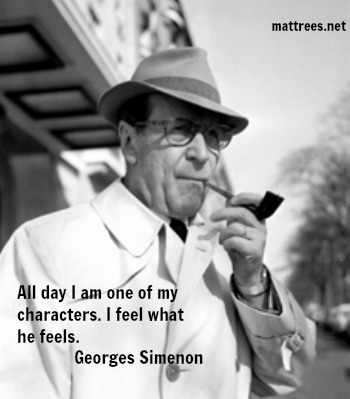

The great Belgian crime noveliest Georges Simenon described writing as exhausting. Not because he worked long hours, but because he inhabited the character about whom he was writing. If the character felt tense, Simenon made himself feel tense. If the character was devastated by some event, Simenon worked himself up into a hell of a state. That way he could write from within the experience. To get what I mean, read The Saint Fiacre Affair, most often published in English under the title Maigret Goes Home

The great Belgian crime noveliest Georges Simenon described writing as exhausting. Not because he worked long hours, but because he inhabited the character about whom he was writing. If the character felt tense, Simenon made himself feel tense. If the character was devastated by some event, Simenon worked himself up into a hell of a state. That way he could write from within the experience. To get what I mean, read The Saint Fiacre Affair, most often published in English under the title Maigret Goes Home

Many writers ignore this vital technique. In fact, when I've described this to other writers and told them that I try to do it, some of them mock the idea. But other creative artists, such as actors, view this technique as the basis of their craft.

In writing MOZART’S LAST ARIA, my historical novel about Mozart’s death, I talked with classical musicians about how they prepare to play. I needed to know this, so I could convey how Nannerl, Mozart’s sister, ought to approach the pieces she plays in the book.

Some classical musicians begin by associating a color with the piece they’re playing. Then they ask themselves, “What season does this make me think of?” Before they play, they’ll have that color and that season in their head. It makes them receptive to the emotion with which they must infuse the piece.

Try doing the same thing when writing. It’ll take you beyond plot and any sense of what the chapter you’re writing ought to be “about” – those are just details — and leave you with the essential emotional content.

Related articles across the web

Maigret #13: The Saint-Fiacre Affair by Simenon (Pocket, 1942)

Maigret #13: The Saint-Fiacre Affair by Simenon (Pocket, 1942)

Behind the book: Mozart's Last Aria

Behind the book: Mozart's Last Aria

Criminal Minds: Georges Simenon

Criminal Minds: Georges Simenon

In praise of Georges Simenon's French detective

In praise of Georges Simenon's French detective

The great Belgian crime noveliest Georges Simenon described writing as exhausting. Not because he worked long hours, but because he inhabited the character about whom he was writing. If the character felt tense, Simenon made himself feel tense. If the character was devastated by some event, Simenon worked himself up into a hell of a state. That way he could write from within the experience. To get what I mean, read The Saint Fiacre Affair, most often published in English under the title Maigret Goes Home

The great Belgian crime noveliest Georges Simenon described writing as exhausting. Not because he worked long hours, but because he inhabited the character about whom he was writing. If the character felt tense, Simenon made himself feel tense. If the character was devastated by some event, Simenon worked himself up into a hell of a state. That way he could write from within the experience. To get what I mean, read The Saint Fiacre Affair, most often published in English under the title Maigret Goes HomeMany writers ignore this vital technique. In fact, when I've described this to other writers and told them that I try to do it, some of them mock the idea. But other creative artists, such as actors, view this technique as the basis of their craft.

In writing MOZART’S LAST ARIA, my historical novel about Mozart’s death, I talked with classical musicians about how they prepare to play. I needed to know this, so I could convey how Nannerl, Mozart’s sister, ought to approach the pieces she plays in the book.

Some classical musicians begin by associating a color with the piece they’re playing. Then they ask themselves, “What season does this make me think of?” Before they play, they’ll have that color and that season in their head. It makes them receptive to the emotion with which they must infuse the piece.

Try doing the same thing when writing. It’ll take you beyond plot and any sense of what the chapter you’re writing ought to be “about” – those are just details — and leave you with the essential emotional content.

Related articles across the web

Maigret #13: The Saint-Fiacre Affair by Simenon (Pocket, 1942)

Maigret #13: The Saint-Fiacre Affair by Simenon (Pocket, 1942)  Behind the book: Mozart's Last Aria

Behind the book: Mozart's Last Aria  Criminal Minds: Georges Simenon

Criminal Minds: Georges Simenon  In praise of Georges Simenon's French detective

In praise of Georges Simenon's French detective

Published on February 16, 2014 22:37

•

Tags:

georges-simenon, writing, writing-style, writing-tips

Writing crime fiction: Character drives plot

Memorable characters are at the heart of crime writing success

See what I have to say about this idea on my blog.

See what I have to say about this idea on my blog.

Published on February 18, 2014 03:56

•

Tags:

crime-fiction, joseph-wambaugh, writing, writing-tips

Plot a thriller with this diagram

The diagram shows the major points in plotting a thriller

This diagram is a framework for writing a thriller. It's based on my experience writing crime fiction and on studying how other writers do it. I'll go into more detail about each of the stages in future posts and I'll add some points to the diagram as we go along. But if you follow this, you'll have a thriller that'll keep you and your readers in a state of tension until the last page. It's a companion piece to my podcast How to Structure and Plot a Book. While you're waiting for my coming posts, come up with a premise for a thriller and see if you can plot out how you'd develop it right through this diagram. Let me know what you come up with.

Related articles across the web

Podcast: How to structure and plot a book

Podcast: How to structure and plot a book

Writing crime fiction: Do you plot or not?

Writing crime fiction: Do you plot or not?

Six Basic Tips For Writing Thriller Stories

Six Basic Tips For Writing Thriller Stories

Conventions Of A Thriller Film.

Conventions Of A Thriller Film.

Thriller conventions

Thriller conventions

This diagram is a framework for writing a thriller. It's based on my experience writing crime fiction and on studying how other writers do it. I'll go into more detail about each of the stages in future posts and I'll add some points to the diagram as we go along. But if you follow this, you'll have a thriller that'll keep you and your readers in a state of tension until the last page. It's a companion piece to my podcast How to Structure and Plot a Book. While you're waiting for my coming posts, come up with a premise for a thriller and see if you can plot out how you'd develop it right through this diagram. Let me know what you come up with.

Related articles across the web

Podcast: How to structure and plot a book

Podcast: How to structure and plot a book  Writing crime fiction: Do you plot or not?

Writing crime fiction: Do you plot or not?  Six Basic Tips For Writing Thriller Stories

Six Basic Tips For Writing Thriller Stories  Conventions Of A Thriller Film.

Conventions Of A Thriller Film.  Thriller conventions

Thriller conventions

Published on February 20, 2014 00:03

•

Tags:

crime-fiction, how-to-plot, plot, thrillers, writing, writing-tips

Write a thriller: 2 tips to get your book started

Just write, don't wait for inspiration. And understand the 3-Act structure

Nora Roberts (aka J.D. Robb) knows what she's talking about. To get going on your thriller -- or any other kind of writing -- you have to just do it. Don't worry about how it sounds or feels. Just write. She has 209 romance novels and a bunch of crime fiction to her name proving that she's right. The somewhat less prolific Ernest Hemingway said that "first drafts are shit." But all novels have a first draft. So get your Hemingwayesque excrement out there and then you can start to mould it into... Ah, let's move on.

The basic outline of a thriller plot -- or of any other crime story -- looks like this:

The part we're going to chat about in this post is up top:

Why three acts? Shakespeare used five, but three is the way most stories are told today. (I've included the idea of a fourth act, which we'll go into later.) You set things up in Act 1. The hero must push on into the story or something dreadful's going to happen. In Act 2, the hero chases about. The hero tries to figure out what's in his way. In Act 3, the hero knows what he has to do to wrap things up. So he sets about doing it.

We'll move down the plot diagram in the posts I'll be adding to my blog this week. Keep reading.

Related articles across the web

Tyson Adams' Rules of Thriller Writing

Tyson Adams' Rules of Thriller Writing

thriller movie conventions

thriller movie conventions

Conventions of a Thriller

Conventions of a Thriller

Nora Roberts (aka J.D. Robb) knows what she's talking about. To get going on your thriller -- or any other kind of writing -- you have to just do it. Don't worry about how it sounds or feels. Just write. She has 209 romance novels and a bunch of crime fiction to her name proving that she's right. The somewhat less prolific Ernest Hemingway said that "first drafts are shit." But all novels have a first draft. So get your Hemingwayesque excrement out there and then you can start to mould it into... Ah, let's move on.

The basic outline of a thriller plot -- or of any other crime story -- looks like this:

The part we're going to chat about in this post is up top:

Why three acts? Shakespeare used five, but three is the way most stories are told today. (I've included the idea of a fourth act, which we'll go into later.) You set things up in Act 1. The hero must push on into the story or something dreadful's going to happen. In Act 2, the hero chases about. The hero tries to figure out what's in his way. In Act 3, the hero knows what he has to do to wrap things up. So he sets about doing it.

We'll move down the plot diagram in the posts I'll be adding to my blog this week. Keep reading.

Related articles across the web

Tyson Adams' Rules of Thriller Writing

Tyson Adams' Rules of Thriller Writing  thriller movie conventions

thriller movie conventions  Conventions of a Thriller

Conventions of a Thriller

Published on February 24, 2014 02:24

•

Tags:

crime-fiction, j-d-robb, nora-roberts, thrillers, writing, writing-tips