Matt Rees's Blog - Posts Tagged "raymond-chandler"

The (Forgotten) Book You Have to Read: Simenon's 'Saint-Fiacre Affair'

Crime fiction blog The Rap Sheet runs a regular feature prompting authors to write about a "forgotten" book that merits new attention. This last week the blog's editor asked me to suggest a book. I wrote about Georges Simenon's "The Saint-Fiacre Affair" (aka "Maigret Goes Home"). It's an early Inspector Maigret novel (1932) and not what you'd expect, if you're used to the later, somewhat more cosy novels in the Belgian writer's series. It's a tough, atmospheric book about returning to the place of one's birth which -- for me -- has a personal resonance. Read on for my little essay about this great book -- and while you're at it, let me know what forgotten novel you'd have written about.

Crime fiction blog The Rap Sheet runs a regular feature prompting authors to write about a "forgotten" book that merits new attention. This last week the blog's editor asked me to suggest a book. I wrote about Georges Simenon's "The Saint-Fiacre Affair" (aka "Maigret Goes Home"). It's an early Inspector Maigret novel (1932) and not what you'd expect, if you're used to the later, somewhat more cosy novels in the Belgian writer's series. It's a tough, atmospheric book about returning to the place of one's birth which -- for me -- has a personal resonance. Read on for my little essay about this great book -- and while you're at it, let me know what forgotten novel you'd have written about.(Editor’s note: This is the 80th installment of our ongoing Friday blog series highlighting great but forgotten books. Today’s selection has been made by Welsh-born novelist-journalist Matt Beynon Rees, author of the Dagger Award-winning series of Palestinian crime novels featuring Bethlehem sleuth Omar Yussef. The Fourth Assassin, in which Omar uncovers an assassination plot in the Brooklyn Palestinian community, is published this week by Soho Crime. Rees also blogs at The Man of Twists and Turns.)

For a couple of decades now, I’ve lived around the world as a journalist and writer. It’s been 22 years since I quit the place where I grew up. If I’d been a happy kid, I’d probably never have left. So whenever I go back for a visit, I become quiet, silenced by a bitter nostalgia and regret. Maybe that’s why I love this somber, atmospheric early episode in Georges Simenon’s Maigret series, in which “le Commissaire” goes back to his childhood village.

The Saint-Fiacre Affair (also known as Maigret Goes Home) was originally published in 1932, three years after French Inspector Jules Maigret first made his appearance in a series that would eventually amount to 103 novels. The Belgian writer created a figure whose fat belly, soft hat, and pipe would become iconic.

Maigret appeared in so many movies and television adaptations--for Saint-Fiacre alone there’s a 1959 French-language movie with Jean Gabin and two British TV versions--that it’s easy to think of him with the cozy familiarity we often ascribe to endlessly reproduced old-timers like Miss Marple. But Simenon wasn’t willing to look at the world the way Agatha Christie did. He had a lot more in common with his great U.S. crime-writing contemporaries. In fact, in Saint-Fiacre, he makes the lugubrious Raymond Chandler look like a breezy teenage girl humming a happy tune as she skips down a sunny small-town street in her bobby socks. Imagine that.

Simenon’s first editor wrote to him: “Your books aren’t real police novels. They aren’t scientific. They don’t play by the rules. There’s no love story in them. There’re no sympathetic characters. You won’t have a thousand readers.” Well, 550 million copies printed shows what that guy knew about potential sales. But he was right about the way Simenon’s books worked. No real good guys and nothing--certainly not love--untainted by the grasping desire to escape a society of dying traditions and internal immigration.

Most readers who actually get to Maigret these days probably know the novels of the character’s heyday in the late 1960s, early ’70s--Maigret and the Wine Merchant, Maigret’s Boyhood Friend. By then, the inspector had slipped into a comfortable domesticity. He’d interrupt his investigation to see a movie with his wife or to sip a white wine at a café--even if he was still terse and hard when it came to the crunch. In reading those books, it’s easy to forget that in the 1930s and 1940s, Simenon was an exponent of a particular mélange of existentialism and gritty detective fiction that’s quite strikingly harsh even today. (Check out 1948’s Dirty Snow for a rough ride with a profiteer during the German occupation. There’s a guy who really doesn’t care about anyone or anything. In your face, Albert Camus!)

The Saint-Fiacre Affair begins with Maigret waking up in the inn of the village of Saint-Fiacre. At first he doesn’t recognize where he is. As it dawns upon him, he’s flooded with a heavy sense of darkness. He has returned to the village where he grew up to investigate a crime which is about to happen. (His office in the Paris police headquarters received a note saying that “A crime will be committed at the Saint-Fiacre Church during the first mass of the days of the dead.”)

As he strolls through the village, people glance at him curiously. They seem to recognize him, but can’t place the face of the son of the former steward at the local château, a face that left their community 35 years previously to pursue a career in the capital. All other traces of Maigret’s family are gone from the village and he wanders it sensing somehow that its very stones are unwelcoming.

When characters eventually recognize him or when he owns up to being from Saint-Fiacre, they seem to wonder what the hell could’ve brought him back. It’s clear they don’t trust him. There’s no hale slap on the back or curiosity about what he’s been doing all these years. Simenon captures the isolation and suspicion of the French peasant for the big city perfectly. What these people are signaling to Maigret--and what he instinctively realizes--is that he may have been born in Saint-Fiacre, but the moment he left he ceased to belong to it. They owe him nothing. He’s on his own.

If you’ve ever been back to a place where you weren’t happy as a kid, a place from which you wanted to escape, you’ll feel as though you’re reading your diary, not a detective novel.

At the first mass, the Countess of Saint-Fiacre dies of a heart attack. With his crime delivered as promised, Maigret uncovers a clue at the scene and tracks the killer. But it’s really his own despondent sense of alienation that’s at the heart of this novel.

Published on February 07, 2010 06:07

•

Tags:

albert-camus, belgian-fiction, belgium, blogs, crime-fiction, dirty-snow, exotic-fiction, french-fiction, georges-simenon, jean-gabin, maigret, maigret-goes-home, raymond-chandler, the-fourth-assassin, the-rap-sheet, the-saint-fiacre-affair

Crime fiction with a vengeance

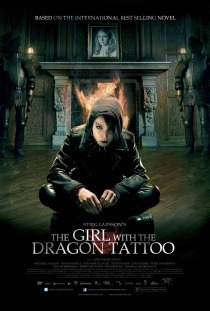

The Swedish title of Part I in Stieg Larsson’s Millennium Trilogy was “Men Who Hate Women.” Which shows that you can write a huge international bestseller and not know why people would read your book.

Larsson’s U.K. publisher changed the title to “The Girl With the Dragon Tattoo.” With his original title, Larsson would’ve been a posthumous hit (he died in 2004 of a heart attack at the age of 50) in Sweden, where he was well-known as a Communist campaigner against racism and the extreme right. But he probably wouldn’t have beaten the rest of the recently popular pack of Nordic crime writers from Henning Mankell to Jo Nesbo.

It’s the title change and its focus on a character who’s both aide to the sleuth and victim of violent crime that made Larsson the second-biggest selling novelist in the world last year, after Khaled “A Thousand Splendid Suns” Hosseini.

All the other Nordic writers focus on the detective, which is after all the traditional route in crime fiction. We’ve bought 40 million Mankell novels to follow Inspector Wallander as he mopes his way to the villain’s doorstep.

You could read Larsson’s book like that, too: Mikael Blomqvist, magazine editor and irresistible ladies man, is commissioned to unravel an old murder mystery on a remote Swedish island. But it’s his assistant, a rape-victim filled with hate for her persecutors (the men who hate women), who’s really the heart of the book.

While Blomqvist is working the island case — a fairly typical “closed room” mystery, similar to the ones in which Agatha Christie’s sleuths used to inform us that “one of the people in this room is the murderer” — Lisbeth Salander is secretly setting up the vigilante vengeance that provides the book’s smooth twist in the tail.

No one reads beyond page 50 for Blomqvist. Just Salander. Which is why the work of a Swedish Communist is now being taken up by Sony Pictures for a Hollywood version probably to be directed by David Fincher (who made “Zodiac”), produced by Scott Rudin (“No Country for Old Men”) and scripted by Steve Zaillian (who won an Oscar for his adaptation of “Schindler’s List”).

So many readers warmed to Salander — the series has sold 27 million copies in 40 countries so far — that all three novels in the series have been made into movies in Sweden already. The first came out in the U.S. this month and the other two will be released in the summer.

USA Today urged viewers not to wait for the Hollywood version, calling the Swedish flick “indelibly great.” (Indelible, like a dragon tattoo, get it?) In an example of praising the atmosphere while half-overlooking a flaw in the central element of the movie, reviewer Claudia Puig wrote: “Though the relationship between Lisbeth and Mikael isn't fully developed and a few plot coincidences feel contrived, The Girl With the Dragon Tattoo artfully and intelligently fuses a punk sensibility to an epic tale.”

Maybe it’s wise not to wait for Hollywood, if it’s punk sensibility that floats your boat.

Of course, Puig’s quibble is a red alert for likely scriptwriter Zaillian. You have to buy Lisbeth and Mikael, otherwise “The Girl With the Dragon Tattoo” is really a drag.

Let’s go back to the novel.

It’s 554 pages in my British softcover version — the first book of three equally bulky volumes, in case you haven't already read them. Much of that is the sort of thing you might read in a campaigning magazine such as Expo, the publication of which Larsson was the editor. It’s written in the chatty simple language that magazine — and, increasingly, thriller — editors like, because it’s direct and lacking in imagery, so you keep turning the pages. You’ll never have to stop and say, “Hey, ‘She gave me a smile I could feel in my hip pocket.’ Nice image, Stieg Larsson.”

(You won’t, because that’s Raymond Chandler. “Farewell, My Lovely,” chapter 18.)

That’s no problem for a screenwriter. Hollywood can do its own wisecracks, and other literary imagery is usually dropped before an actor opens his lips.

Zaillian can surely cut most of the lengthy portions of the book which Larsson probably liked best. There are long disquisitions on rape statistics in Sweden and background segments on the local business scene. Take Lisbeth’s repeated rape by her legal guardian. It leads to a page and a half of this:

“Guardianship is a stricter form of control in which the client is relieved of the authority to handle his or her own money or to make decisions regarding various matters.”

There’s more: “Taking away a person’s control of her own life … is one of the greatest infringements a democracy can impose … For the most part the Guardianship Agency carries out its activities under difficult conditions … Occasionally there are reports that charges have been brought against some trustee or guardian who has…”

If Karl Marx had written “Das Kapital” in the evenings as a thriller, it might’ve had more zip than Larsson’s preachy liberal legalisms. Just so long as Engels had changed the title to “The Guy With the Dialectic Theory.”

Niels Arden Oplev’s Swedish movie version boils down to a 152-minute procedural that’s quite televisual in its look. That’s too long for a Hollywood thriller, so Zaillian will have to pare it even more.

So what’s left when you take out the tedium? (Don’t get me wrong, a lot of readers tell me they love the tedious parts of Larsson. They soothe you when you’re sick in bed or trying to take your mind off work at the beach. You forget your troubles, immersed instead in how rotten it is to be a Swedish woman.)

Which returns us to Lisbeth. She drives the narrative and, perhaps because women fall too easily for Mikael, she’s where all the sexual tension lies, too. (The book is big on titillation and the Swedish movie doesn’t skimp on a graphic rape scene.) It’s Lisbeth who’ll take you beyond the statutory confrontation with the villain. She makes the book memorable.

Better hope Hollywood doesn’t change the title.

(I posted this on GlobalPost.com)

Published on March 30, 2010 04:43

•

Tags:

a-thousand-splendid-suns, claudia-puig, crime-fiction, das-kapital, david-fincher, farewell-my-lovely, henning-mankell, hollywood, inspector-wallander, jo-nesbo, karl-marx, khaled-hosseini, lisbeth-salander, mikael-blomqvist, millennium-trilogy, movies, niels-arden-oplev, no-country-for-old-men, nordic-crime-fiction, raymond-chandler, reviews, schindler-s-list, scott-rudin, steve-zaillian, stieg-larsson, swedish-crime-fiction, the-girl-with-the-dragon-tattoo, usa-today, zodiac

Stealing the novel

If there’s one thing that authoring a series of novels will teach you, it’s that you can’t wait for inspiration. But you can prompt it, give it little electric shocks that’ll keep it bubbling within you. Here are a few methods I use to do that.

If there’s one thing that authoring a series of novels will teach you, it’s that you can’t wait for inspiration. But you can prompt it, give it little electric shocks that’ll keep it bubbling within you. Here are a few methods I use to do that.I go to the places I’m writing about. I talk to people who might be similar to (or even the basis for) my characters. I read about them and their world. I engage in the same activities in which they specialize. But I also read about entirely different subjects – so long as they’re extremely well-written.

Some of these ideas sound self-evident. I’ve written a series of Palestinian crime novels, so it stands to reason that I’ve spent the last decade and a half in Gaza, Bethlehem, Nablus, Jerusalem, tasting and smelling and talking and looking. I even force myself to read the drivel that gets written about this place in journalism and nonfiction—occasionally I come across something good, but mainly it just gets me down. How many times can you listen to a mediocre pop song? Well, that’s how most Middle East journalism sounds in my ear.

For a novel I have coming out next year about Mozart, I learned to play the piano. I learned that I wasn’t much good at it, but I also saw inside the music in a way I couldn’t have done merely by listening.

Not so obvious, however, might be the wide reading. A number of writers I’ve met or read about say they don’t have time to read anything that isn’t directly related to their research. In other words, if I’m writing about Berlin, it’s goodbye to Raymond Chandler for the next 12 months.

Well, T.S. Eliot wrote that “Immature poets imitate; mature poets steal.” I can look back at my literary efforts as an undergraduate and see what imitation there was throughout all of it. Now I’m mature (I try to fight it; I work out; but I concede, I’m maturing…) and I’ve figured out how to steal.

What Eliot meant was that it takes a while, as a writer, to realize how to make things your own. That means going beyond the plagiaristic imitation of youth, which is humble and filled with homage, to the confident sense that whatever you see another writer do, you can do it better. Then when you read something good, it doesn’t appear in your work as the same thing—it spurs you to develop your own spin on the thought that’s provoked in you by what you’ve read.

Let me give you an example. I challenge any one of you to show me a contemporary writer who can build a character in a fuller, more convincing manner than Hilary Mantel, who won the Booker Prize last year for her masterful “Wolf Hall.” If anything, her 1992 classic “A place of Greater Safety,” a novel about the French Revolution, is even more amazing than her now-famous prize-winner.

“Greater Safety” tells the story of the entire revolution through the characters of Robespierre, Danton and Desmoulins. From their childhoods to (it’s a historical novel so I don’t have to give any spoiler alerts) their executions. Each of them is built slowly, and we see their character arc in a way that even they don’t—watch their idealism tainted with violence, until it turns on them. Because we take that journey with them, we care more deeply for them, even as they become murderous and unjust.

The “stealing” comes in whenever I see a point that Mantel uses to build that empathy. Robespierre, we learn, always carries a tiny copy of Rousseau in his pocket. Some time later it’s on his desk and Desmoulins notices it. Just one sentence. A couple hundred pages later someone quotes Rousseau against him and only his close friends understand that he’s entirely defeated. We know he’s a man who has bent principles for his friend Desmoulins, but he can’t desert them completely. It’s a choice between Desmoulins, whom he loves, or the book that he keeps close to his heart. Books always win in contests like that.

That doesn’t make me want to replicate the exact same thing in my next book – that’s what I might’ve tried when I was 19. Instead, I think of ways in which to send a signal to the reader. To plant an object that inspires a character, that takes them on the path on which we follow them in the novel. Until ultimately it underlies their collision with another character; makes compromise an impossible undermining of everything they believe about themselves.

That’s stealing, and it’s a good thing to do.

You can find such moments in the small factoids of history books, if you’re researching a period, or in nonfiction. It’s in poems, where a phrase about a frieze on an urn (“Thou still unravished bride of quietness”) will spark a thought about your memories of your own wedding or of a sexual exploit which you can use for a character in your book.

A writer whose obvious focus is character would be the most direct place to start. In other words, not the kind of ultra-bland snoozing that appears in the short fiction of The New Yorker, which always seems to be written as though it were designed to mimic a relatively dull person telling you a story in a cocktail party or at the counter of a bodega.

Choose something with sweep, like Mantel. Someone with an eye for a mordant detail, like Graham Greene in “The Honorary Consul.” Someone who shows you an entire, devastated culture through the eyes of one man, like Martin Cruz Smith’s investigator Arkady Renko.

A novel’s like a marathon. Stop and sit down at the side of the road and no amount of sprinting will get you to the finish line. You have to write every day and once you’re started you can’t stop. “Stealing” is a way of warming up for the long run.

Published on April 15, 2010 00:12

•

Tags:

a-place-of-greater-safety, berlin, bethlehem, booker-prize, crime-fiction, danton, desmoulins, gaza, graham-greene, hilary-mantel, historical-fiction, israel, jerusalem, martin-cruz-smith, middle-east, mozart, nablus, novels, palestine, raymond-chandler, robespierre, t-s-eliot, wolf-hall, writing

'Exotic' crime fiction makes unpalatable places bearable

“Exotic” crime fiction has taken off in the last decade. People want to read about detectives in far-off places, even if they don’t want to wade through learned histories of those distant lands.

“Exotic” crime fiction has taken off in the last decade. People want to read about detectives in far-off places, even if they don’t want to wade through learned histories of those distant lands.Many of the biggest selling novels of the last decade have been “exotic crime.” You’ll find a detective novel set almost everywhere in the world, from the “Number One Ladies Detective Agency” in Botswana through Camilleri’s Sicily to dour old Henning Mankell in the gloomy south of Sweden.

The success of my co-bloggers at International Crime Authors – with their detectives plying their trade in Thailand, Laos, and Turkey, alongside my Palestinian sleuth Omar Yussef – is also proof that this taste for international crime is more than just a publishing fad. The novels aren’t just Los Angeles gumshoe stuff transported to colder or poorer climes.

Here’s what I think is behind it:

Read a history book or a book of contemporary politics. Often you’ll find a list of the enormous numbers of people destroyed around the world by war and famine and neglect. You won’t get any sense that the world…makes sense. Crime fiction doesn’t purport to save the planet, but it does demonstrate that one man – the detective – can confront a mafia, an international espionage organization, a government and come out with at least a sliver of justice.

And justice is one of the few ideas which can still inspire.

Readers also prefer crime fiction about distant countries over so-called “literary” fiction about such places.

That’s because crime fiction gives you the reality of a society and also, by definition, its worst elements — the killers, the lowlifes — but it also gives you a sense that a resolution is possible. (See above.)

Literary fiction, by contrast, often simply describes the degradation of distant lands. If you read Rohinton Mistry’s “A Fine Balance,” for example, you probably thought it was a great “literary” book, but you also might’ve ended up feeling as abused as his downtrodden Indian characters without the slightest sense of uplift.

Crime fiction doesn’t leave you that way.

Now, that’s also true of the Los Angeles gumshoe. But the international element gives us something else to wonder about in these new novels. Not just because the scene is alien. Rather, it’s because we all trust to some extent that bad guys in Los Angeles will go to jail — or become Hollywood producers. We have faith in the system. So a detective has some measure of backing from the system, and consequently novelists have to push credibility to its limits in order to make him look like he’s taking a risk, to make him look brave.

International crime, when it’s set in the Developing World in particular, can’t be based on that same trust in the just workings of the system. The lack of law and order in Palestine, as I observed it as a journalist covering the Palestinian intifada, was one of the prime reasons I had for casting my novels as crime novels. It was clear the reality wasn’t a romance novel. Gangsters and crooked cops in the West Bank suggested the more vibrant days of the US crime novel back in the time of Chandler and Hammett, when it was much harder to argue that a city or mayor or police chief wouldn’t be in the pocket of the bad guys.

When a detective goes up against such odds in international crime fiction, it’s truly inspiring.

For books that start with a murder, that’s not what you’d expect, but it’s the reason for the success of this new exotic avenue of the crime genre.

Published on May 13, 2010 01:37

•

Tags:

a-fine-balance, alexander-mccall-smith, andrea-camilleri, crime-fiction, dashiell-hammett, detective-fiction, exotic-crime, henning-mankell, italy, laos, los-angeles, middle-east, omar-yussef, palestine, palestinians, raymond-chandler, rohinton-mistry, sweden, thailand, turkey

Going historical

Writing of the disdain expressed for genre novels by critics, Raymond Chandler said that there were just as many bad “literary novels” of the type favored by critics as there were bad genre stories – except that the bad literary novels didn’t get published. In other words, there’s nothing inherent in so-called genre fiction that makes it lesser than “literary” fiction.

Writing of the disdain expressed for genre novels by critics, Raymond Chandler said that there were just as many bad “literary novels” of the type favored by critics as there were bad genre stories – except that the bad literary novels didn’t get published. In other words, there’s nothing inherent in so-called genre fiction that makes it lesser than “literary” fiction.Chandler knew what he was talking about. His great noir novels, such as “The Big Sleep” and “The Long Goodbye,” are must-reads for anyone who wants to know how to build a sentence and a voice, how to create an image that won’t fade a few pages on, how to make people want to read it all over again. His contemporaries in the “literary” field who were more favored by the highbrow critics of his time are these days consigned to the dustbin of college literature courses. (If you don’t believe me, tell me when was the last time you reached for a volume by Upton Sinclair or Pearl Buck?)

But historical fiction is back. Ever since “The Name of the Rose” (published in English in 1983), the genre has accrued greater legitimacy. Last year’s Booker Prize went to a historical novel (“Wolf Hall”) and this year’s looks likely to go to “The Thousand Autumns of Jacob de Zoet” (do an internet search for its author David Mitchell and “genius,” and you’ll see why.)

Even poor old Alexandre Dumas and the swashbuckler have been returned from their long-ago burial under a mound of critical invective. In the last decade or so, Dumas has found his way into the title of a novel by Arturo Perez-Reverte, one of the most notable historical novelists of our time. Perez-Reverte can buckle a swash in the form of his Dumas-derived Captain Alatriste series, but he also has enough modern perversity for one of his novels to have been adapted for the screen by Roman Polanski. (That novel, “The Club Dumas,” even included a reference to Eco, “the professor from Bologna,” in a nod to his role in legitimizing the genre.)

Read the rest of this post on my blog The Man of Twists and Turns.

Published on September 01, 2010 00:06

•

Tags:

alan-furst, alexandre-dumas, arturo-perez-reverte, barbara-nadel, barry-unsworth, caleb-carr, captain-alatriste, caravaggio, crime-fiction, david-mitchell, hilary-mantel, historical-fiction, j-sydney-jones, literary-fiction, mozart, mozart-s-last-aria, new-york, omar-yussef, palestinian, pearl-buck, raymond-chandler, sacred-hunger, the-big-sleep, the-club-dumas, the-long-goodbye, the-name-of-the-rose, umberto-eco, upton-sinclair, west-bank, wolf-hall

Overturning detective fiction: everyone's guilty in my novels

The “Golden Age” of the detective story was the 1920s and 1930s. It was a turbulent period. In Britain, the General Strike. In the U.S., the Depression. Civil war in Spain, and in Germany the rise of the Nazis. Red scares everywhere, fascists too.

The “Golden Age” of the detective story was the 1920s and 1930s. It was a turbulent period. In Britain, the General Strike. In the U.S., the Depression. Civil war in Spain, and in Germany the rise of the Nazis. Red scares everywhere, fascists too.But the detective story was a solace to those who lived in such ugly times. In the model employed by Agatha Christie and Dorothy L. Sayers, the story ended with one criminal fingered by the detective. Everyone else turned out to be innocent. Order was restored. It was as if the writers were saying, Don’t worry about what you read in the newspapers; everything can be fixed and only a small minority are making the trouble.

In my Palestinian crime novels, the opposite is true. Everyone’s guilty. Tat’s the reality I found in Palestinian society, as disaster befell it in the last decade – an intifada, a civil war, and now a horrible stand-off between rival factions. Not any one person’s fault.

I believe that’s a better reflection of the world in which we live. My novels are entertainments, but they aren’t layered with the conservative perspective of the “Golden Age.” I don’t want readers to think that there’s nothing wrong out there, so long as the detective nabs the sole bad guy in the library.

Crime novels today are grittier than the work of Christie. They tend to be closer to the atmosphere of Raymond Chandler, who wrote that the Golden Age stories “really get me down.” But the Chandler ethos of a lone knight facing an utterly corrupt world is largely ignored.

That’s why there are so many novels these days about pedophiles and psychopaths. Such characters are beyond the pale of behavior in which we could imagine ourselves participating. To commit a crime in such novels is to mark oneself out as a deviant. As soon as the deviant is nabbed, the society can go back into its usual calm manner.

I think this is why Scandinavian crime novels have been so popular. Readers like the fact that, while the detective wrestles with the psycho, the society depicted is clearly not so very flawed. As soon as the psycho is nabbed, Sweden will return to its pleasant, polite way of life—something that’s easier to envisage than it would be in a novel set in, say, Bangkok or Gaza. Even in his recent novel, “The Worried Man,” Henning Mankell describes his detective as being no more than “worried about the direction of Swedish society.”

Worried! Can you imagine Omar Yussef, my Palestinian sleuth, being no more than worried? He lives in a society that’s engulfed in disaster. He knows everything’s going to hell and he’s aware that nabbing a single bad guy won’t change that.

The golden age method ought to have been overtaken by reality in a post-Holocaust age. Hannah Arendt wrote of the banality of evil, meaning that people don’t choose good or bad, they just go along. We’d like to see bad guys as pure evil, deciding firmly to commit horrible acts, while the truth of the Holocaust and many other dreadful events is that people are much more likely to operate in a kind of malleable denial.

It’s a vital insight. Yet I find most crime novels are written as though Hitler never happened—as if one wicked man can be blamed for what millions of others simply went along with.

Read the rest of this post on my blog The Man of Twists and Turns.

Published on September 09, 2010 02:19

•

Tags:

agatha-christie, crime-fiction, detective-stories, dorothy-l-sayers, hannah-arendt, henning-mankell, hitler, holocaust, intifada, nordic-crime, omar-yussef, palestine, palestinian, raymond-chandler, the-samaritan-s-secret

Writers, no email until lunch

Raymond Chandler wrote that a writer shouldn’t read letters until lunchtime. The energy that ought to go into his novel would be diverted to correspondence.

Raymond Chandler wrote that a writer shouldn’t read letters until lunchtime. The energy that ought to go into his novel would be diverted to correspondence.If email had been invented 50 years earlier, we might never have had “The Big Sleep.”

Email has an itching urgency that letters don’t have. And a letter leads only to the end of the page – the internet clicks you on into endless pages and seemingly into other worlds. So I’m with Chandler. If you’re a writer, don’t even open your email until you’ve finished writing for the day. Given that most writers have enough creative energy for a three or four hour day tops, you’ll only have to wait until lunchtime, after all.

I’ve interviewed dozens of writers for my blog and I always ask about their writing routine. Many of them say that they dabble on the web until they “feel guilty about wasting time,” then they start writing. Trouble is, by then I think they’ve blown their concentration for the day.

Read the rest of this post on my blog The Man of Twists and Turns.<\a>

Published on September 16, 2010 01:57

•

Tags:

blogs, bronx-zoo, crime-fiction, echardt-tolle, email, internet, lady-gaga, raymond-chandler, the-big-sleep, writing, writing-schedule

'Go **** yourself," and plotting a novel

Raymond Chandler once described an activity (not important what) as being “as elaborate a waste of human intelligence as you can find outside an advertising agency.” I have happened upon a dark corporate art still more wasteful and, being a writer, I see how it’s related to the plotting of a novel.

Raymond Chandler once described an activity (not important what) as being “as elaborate a waste of human intelligence as you can find outside an advertising agency.” I have happened upon a dark corporate art still more wasteful and, being a writer, I see how it’s related to the plotting of a novel.I’ve had a couple of mild run-ins with corporate complaints departments of late – customer service departments as they are known. The service, of course, is the kind of servicing offered by a stallion to a mare.

I’ll sum up what’s been going on, and then I’ll tell you why the “customer service” department is the anti-creative, anti-crime novel acme of our society. I’ll also tell you why I bet Dick Cheney doesn’t like crime novels.

But wait, first, my complaints. I rented a car with Hertz on a recent trip to the UK. I was caught on a speed camera doing 36 miles per hour in a 30 mph zone, and elsewhere doing 45 mph in a 40 mph zone. So I have to pay a fine. Well, I don’t like drivers who speed, so I’ll pay the fine.

Yet Hertz charged me 30 pounds plus tax to let me know that I was liable for these fines. I called to tell them I thought this was excessive and was given a very rude brush-off by a nasty Irish woman. I forgave her, because while I owe 60 pounds plus tax for driving too fast, she personally owes a few billion Euros just for being Irish.

I then wrote to Hertz and received a reply from Lisa Walsh of “Customer Services” in which she said the 30 pounds was to cover Hertz’s expenses. “Our financial controller has set the cost at 30 pounds per fine.” Oh, well, if your financial controller says it’s reasonable, what do I know? Lisa then added: “We appreciate your business and look forward to the opportunity to serve your future rental needs.”

Read the rest of this post on my blog The Man of Twists and Turns.

Published on December 16, 2010 07:28

•

Tags:

american-express, crime-fiction, customer-services, dick-cheney, disneyland-paris, glamorgan, hertz-car-rental, raymond-chandler

For Arabs: democracy, then crime fiction

Crime fiction may not be the first thing on the minds of the protesters taking to the streets for democracy across the Arab world. But one of the offshoots of the downfall of Arab dictators is sure to be an explosion of thrillers and mysteries.

Crime fiction may not be the first thing on the minds of the protesters taking to the streets for democracy across the Arab world. But one of the offshoots of the downfall of Arab dictators is sure to be an explosion of thrillers and mysteries.Until now there has been almost no crime fiction written in Arabic. A couple of little-known writers in Egypt and Morocco have contributed old-fashioned Agatha Christie-style cosies (“One of the people at this oasis is the killer.”) The best Arab detective writer has been Yasmina Khadra, whose series about Inspector Llob is supremely gory and noirish. But Khadra writes in French from exile in France.

I believe Arabs have eschewed crime writing because it’s a democratic genre. One man wants to find out something that a big organization – the CIA, the mafia, the government – wants to keep secret. It’s easy to see why Hosni Mubarak probably wasn’t a fan of Raymond Chandler.

For people who live in democracies, it’s easy to find fiction credible that suggests a man can investigate – and once he fingers the bad guy, the bad guy will be punished. That’s why Scandinavian crime fiction by Henning Mankell et al is so popular: the Nordic societies have us all convinced that an eruption of violence, crime or murder, will soon enough be resolved and life can go back to its usual extreme orderliness.

Not so for the Arab world. Arabs have a deep sense of fatalism. Not only do they lack faith that the bad guy will be punished, they’re quite sure the bad guy will prosper. He’ll drive his Mercedes to his villa directly from the government offices or state-run companies where he rakes off his big take. The ordinary guy will be left to live on $2 a day.

When I came to write my series of Palestinian crime novels, one of the challenges was to make the format of the crime novel work in an environment where law and order didn’t really function or protect ordinary citizens. I did it by demonstrating that while my sleuth, Omar Yussef, might nail one bad guy at the end of the book, he would be left with an awareness that there were many other guilty men who had escaped him. As one German reader put it to me at a book festival, “I like your books because, in the end, everyone’s guilty.” The reason people across the Arab world are rising up is because they don’t want to share the guilt and shame of their broken, repressed societies any more.

Read the rest of this post on my blog The Man of Twists and Turns.

These observations are true even for countries where there isn’t what we’d call a Western-style democracy – which I’d characterize as a democracy where corruption is either extremely well-hidden or disguised as a stock market in which all can supposedly participate. Take Russia, for example. Clearly not the democracy its people might dream of. But nonetheless one in which opposition journalists – at considerable risk to themselves – do function in the face of the state apparatus and its corrupt overlords.

In South Africa, there was almost no local crime fiction under apartheid. When that changed, there was an explosion of crime writing.

The situation in the Arab world is changing now. Which shows that there’s a thirst for democracy, for accountability – and, therefore, for crime fiction.

Published on February 24, 2011 00:55

•

Tags:

agatha-christie, arabs, crime-fiction, democracy, henning-mankell, hosni-mubarak, middle-east, omar-yussef, raymond-chandler, writing, yasmina-khadra

Unpolished Fleming and Paranoid Mankell

I’ve seen two things in the last week that allowed me to compare something

I’ve seen two things in the last week that allowed me to compare somethingof the way crime writers used to appear in public and their present avatars.

It only made me wish for the good old days even more than I used to.

The comparison is between: a delightful radio chat on the BBC in 1958 between Raymond Chandler and Ian Fleming; and a load of paranoid weirdness from Henning Mankell.

First, Chandler and Fleming. Listen to their talk. I rarely bother listen to

an entire half hour of anything online, but I’m telling you this is

beautiful. Both of them are unpolished as all hell. For anyone who’s been to

a book fair and seen the well-honed wisecracks and calibrated personae of today’s authors, this’ll be refreshing.

When Fleming asks Chandler to explain how a hit is done in America (which

surely seemed like a very dangerous place to the average BBC listener of

half a century ago), gruff old Ray puffs on his pipe and spins an unlikely tale of gunmen brought to New York from that den of iniquity, Minneapolis. It

impresses Fleming so much that he refers to it in summing up the broadcast

as something very enlightening and shocking and underground that Chandler

has given us.

But most of all from Chandler’s side there’s the news that he intended

another Marlowe novel in which the great shamus would be married (see the

end of “Playback”) and, though he’d love his wife, he’d be frustrated by her

friends and the ease with which he lives.

Fleming, meanwhile, is very British and self-deprecating, pointing out

several times that his novels are pale shadows of what Chandler writes. In

turn, Chandler is amazed that Fleming writes a novel in two months during

his annual Jamaica vacation, having never written one faster than three

months himself. He then opines that “you starve 10 years before even your

publisher knows you’re any good.” Amen to that.

This truly beautiful conversation – hearing the voices of these fellows is

priceless in itself – was in stark contrast to Henning Mankell’s appearance

in an Israeli newspaper last week.

The starting point for Mankell’s piece was his deportation from Israel a

year ago. He was among the pro-Palestinian activists aboard a flotilla of

ships headed for Gaza, which was intercepted by Israeli commandoes. Aboard one of the ships, the commandoes and activists fought and nine activists were killed. Mankell was among those brought back to Israel on the boats and then deported.

His article in Ha’aretz last week goes through the story of a Facebook page

opened in his name. It declared support for the Lebanese Islamists of

Hezbollah and other positions he claims not to share. Facebook took the site

down twice at Mankell’s request. Mankell wonders who was behind the Facebook page.

To anyone who’s been in the Middle East, the most obvious answer is: a

Palestinian supporter saw that Mankell was on their side and decided to

hijack his name for some other causes to which he or she thought Mankell

might be inclined. Or at least that they’d be causes to which readers might

assume Mankell was inclined, knowing his position on Palestine.

But no. With a circuitous logic never apparent in his plodding Wallander

novels, Henning tells us that he heard the Israeli government wanted to use

social media to attack its enemies. Is this behind the “Henning Mankell”

Facebook page? Twice he writes: “Who would benefit from this?”

Read the rest of this post on my blog The Man of Twists and Turns.

Published on June 23, 2011 05:46

•

Tags:

bbc, crime-fiction, gaza, gaza-flotilla, henning-mankell, ian-fleming, inspector-wallander, israel, james-bond, palestine, philip-marlowe, raymond-chandler