‘He has left usforsaken!’ The Well of Lonliness and the Obscene Publications Act

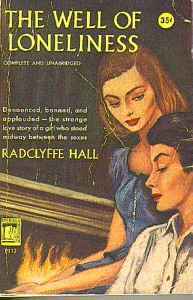

1951 Edition of Well of Lonliness

At the same time Lawrence was castigating ‘grey elderly ones,’ in his pamphlet, another trial over obscene literature was taking place, one that holds augurs for the mid-century shift that produced the 1959 obscenity law—the 1928 trial over Radclyffe Hall’s The Well of Loneliness. Like Maurice and The Rainbow, Hall’s novel is a coming of age story that documents a characters childhood and adulthood. Unlike Lawrence, Hall was not interested in frank depiction and description of sexuality. In fact, the most ‘obscene’ or suggestive line in the novel occurs when the main character kisses another woman “full on the lips, as a lover.”

While Forester was much more cautions and hesitant about publishing a novel that discussed or featured homosexuality, Hall was not reserved at all. Combining Forester’s agenda with Lawrence’s agressive writing style, Hall published the Well of Lonliness in 1928 and almost immediately brought legal trouble on herself and her published. Although it would be easy to propose that it was Hall’s mention of homosexuality brought down official censure, the fact that Virginia Woolf published a book (Orlando) in the same year and on the same topic means that is not likely. The difference is that Hall treated The Well of Loneliness as a polemic against the British establishment, especially the homophobic attitudes of the time

Radclyffe Hall

The Well of Loneliness tells the story of Stephen Gordon, the daughter—despite the name—of two upper-class English parents, Anna and Sir Philip Gordon. Her masculine name was given to her by her father. When Anna conceives, Sir Philip is struck by “how much he longed for a son” and they take to calling the fetus Stephen. Unfortunately, as the narrator puts it, “’Man proposes—God disposes,’” and Stephen is born a girl. Sir Philip however, “insisted on calling the infant Stephen…[and] was stubborn, as he could be at times over whims.” From a very young age however, Stephen manifests signs of ‘sexual inversion’ as Ellis called it, and “became aware of an urgent necessity to love. She adored her father, but that was quite different… it was other with Collins, the housemaid.” When Stephen becomes infatuated with Collins her father notices and begins to “study his daughter gravely,” reading late at night a book by a certain German, Karl Heinrich Ulrichs—the first sexologist to propose a theory of homosexuality. He is unable to tell his wife of his discovery and:

committed the first cowardly action of his life. . . In his infinite pity for Stephen’s mother, he sinned very deeply and gravely against Stephen, by withholding from that mother his own conviction that her child was not as other children. . . ‘There’s nothing for you to understand,’ he said firmly, but I like you to trust me in all things.

From this passage you can see how Hall uses the characters and the events in the book to pass judgement and critique the culture of England.

Stephen’s first inkling that something might be different about her comes when a friend named Martin confesses his love for her and she “stare[ed] at him in a kind of dumb horror, staring at his eyes that were clouded by desire, while gradually over her colourless face there was spreading an expression of the deepest revulsion—terror and revulsion.” It is only when she falls in love with an older woman, Angela Crossby, and declares it, does the book reach its rhetorical (and obscene) height:

Stephen answered ‘I know that I love you, and that nothing else matters in the world’. . .all that [Angela] was, and all that she had been and would be again, perhaps even to-morrow, was fused at that moment into one mighty impulse, one imperative need, and that need was Stephen. Stephen’s need was now hers, by sheer force of its blind and uncompromising will to appeasement. Then Stephen took Angela into her arms, and she kissed her full on the lips, as a lover.

Still, the idyll does not last, and the discovery of the affair by Stephen’s mother causes her to say “unnatural… this thing you are is a sin against creation.” It is in this moment that Stephen “found her manhood,” and when she discovers her father’s books on sexology, Hall paints a pathetic (in the pathos sense) picture: holding her fathers “old well-worn Bible. [Stephen] demand[ed] a sign from heaven—nothing less than a sign from heaven she demanded. The Bible fell open near the beginning. She read: ‘And the Lord set a mark upon Cain…’ Then Stephen hurled the Bible away.”

The rest of the novel continues more or less in this sense, with Hall creating scenes to show that Stephen is congenitally ‘inverted’ and blameless for her identity. She becomes a novelist, and then serves as an ambulance driver in the War, where she falls in love with another woman named Mary. By the end of the novel, she determines that in order to ‘protect’ Mary, she must ‘martyr’ herself and send Mary away. Her novel ends with a famous appeal that describes the ghosts of all the people she knew

calling her by name, saying… ‘Stephen, Stephen, speak with your God and ask Him why He has left usforsaken!’. . . And now there was only one voice, one demand; her own voice into which those millions had entered. . .’God,’ she gasped, we believe; we have told You we believe. . .We have not denied You, then rise up and defend us. Acknowledge us, oh God, before the whole world. Give us also the right to our existence!’

Hall’s brazenness and forthrightness was something that the British Home Office could not tolerate, especially as her publisher began importing books that had been secretly printed in Paris. Relying on their usual strategy of targeting a publisher and thereby bypassing the danger of a trial about literary merit, the authorities organized an elaborate sting operation to seize all copies of the book in England.

Unlike Lawrence or Ellis, Hall’s publisher had already decided to stand by her and they had organized a massive legal strategy, a trap that the Home Office fall right into. When the publisher was named in the indictment, he used a loophole in the Obscene Publications Act to say that “Miss Radclyffe Hall wished to be heard under section 32 of the Customs Act as ‘another person,’” allowing her to go on trial. She would be able to speak her ‘one voice, one demand.’ Within two weeks she managed to line up the ‘cream’ of the British literary establishment to testify in her favor: Arnold Bennett, T.S. Eliot, E.M. Forster, Julian Huxley, Rose Macaulay, George Bernard Shaw, Lytton Strachey, and Leonard and Virginia Woolf.

Not all of these figures were there enthusiastically—many of them thought that Hall was too daring, too polemical, and risked exposure and scandal to the entire literary world. Woolf commented on this in her letters: “most of our friends are trying to evade the witness box; for reasons you may guess. But they generally put it down to the weak heart of a father, or a cousin who is about to have twins.” Woolf also expressed reservations over Hall and her book: “no one has read her book; or can read it… so our ardour in the case of freedom of speech gradually cools… we are already beginning to wish it unwritten.”

Luckily for Woolf, she would not end up testifying. The defense lawyer opened his case by saying that it was his intention “to call his distinguished witnesses to testify that the book was not obscene, and those who had passed the 1857 Obscene Publications Act never intended it to be used against such a book.” The purpose of the trial became immediately clear—the defeat of the Hicklin definition of obscene literature. Unfortunately, the prosecution had chosen its judge wisely, and the judge had pre-determined that The Well of Loneliness was obscenity, according to the files of the Director for Public Prosecution examined by Alan Travis. Using the powers of the 1857 Act that was under question, Justice Biron declared that he had the right to define obscenity:

The evidence that is being offered me is expert evidence as to whether or not the book is a piece of literature. That is not the point. The book may be a very fine piece of literature and yet be obscene. Art and obscenity are not disassociated. . .I agree it has considerable merits, but that does not prevent it from being obscene, and therefore I shall not admit this expert evidence.

As Woolf put it, “in what cases is evidence allowable? This last, to my relied, was decided against us: we could not be called as experts in obscenity, only in art.” This episode also shows the continuing importance of judges in our story on the history of obscenity. Indeed, much of this story is impossible without them.

With the very purpose of the trial invalidated, Hall’s defense collapsed. They were unable to prove that the book had merit or that the 1857 Obscene Publications Act was being used in the wrong way—the Act itself was being used to suppress the questioning of the Act. When the judge announced his decision a week later, he was “clear that it was lesbianism itself rather than any particular passage of the book that was being condemned… the better an obscene book is written, the greater is the public to whom it is likely to appeal. The more palatable the poison, the more insidious it is.” After an hour of his speech, Hall seemed to try to cry out with the voice at the end of her novel

Miss Radclyffe Hall: ‘I protest, I emphatically protest.’ Sir Charles Biron: ‘I must ask you to be quiet.’

Hall: ‘I am the author of this book—‘

Biron: ‘If you cannot behave yourself in Court I shall have to have you removed.’

Hall: ‘Shame!’

and was silenced. Furthermore, Hall’s appeal was denied and, much to her dejection, all copies of her book were destroyed in England and the Commonwealth countries of Australia, New Zealand, India, South Africa, and Canada.

The 1928 trial of The Well of Loneliness was a formative and important one for England’s literati. Over 40 of them had been present at the trial, and the other 115+ that had been invited no doubt followed the trial closely. In many ways, this would mark the low point for the writers and the high point for the application of the 1857 Obscene Publications Act and its Hicklin Test. The first sign that the tide was shifting was the already-mentioned 1929 symposium on “The ‘Censorship’ of Books” in which several of Hall’s key experts would argue for the need for reform. Ellis, for example noted that “it is said, indeed, that we have no censorship. If that is so, we have what is worse…call it the Inquisition.”

Forster commented that “I consider that the Act, as at present interpreted, is both unfair to writers and against the public interest, but all I can do is indicate [it]… Non-pornographic books, like The Well of Loneliness, ought not to be suppressed.” Woolf herself even contributed, arguing that the law was harmful to England and “even more serious is the effect upon the writer… [he] is uncertain what may or may not be judged as obscene… he will be asked to weaken, to soften, to omit.” The symposium and its arguments represented the first organized effort by writers to argue in public about the law.

Furthermore, Hall’s trial was instructional to American publishers and lawyers, who would learn the lessons of Hall’s trial well. In February of the following year, the American publishers Covici-Friede bought the rights to the book from Knopf, who refused to publish after the British trial. They then hired Morris Ernst as their lawyer, the co-founder of the ACLU and the author of a book on the legal history of obscenity, To The Pure. Ernst and Covici-Friede seem to have learned three things from the first trial:

1) the defense would have to exercise control over how and by whom the book would be seized,

2) the Obscene Publications Act and the Hicklin Test would have to be the central target of the trial, not societal acceptance of lesbianism, and

3) the literary merit of the work would have to be proved and linked to the original intentions of Campbell when writing the 1857 Act.

The Logo of the NYSSV

They sent a copy of the first American edition of The Well of Loneliness to the New York Society for the Suppression of Vice, who fell for the bait. Charges of obscenity were brought against the publishers in New York by the NYSSV and attorney general of New York. But, by April of 1929, after reading the book, the judges of the New York Court of Special Sessions cleared the book of any obscenity charges, stating that: “the book in question deals with a special social problem, which, in itself, cannot be said to be in violation of the law unless it is written in such a manner as to make it obscene… and tends to deprave and corrupt minds open to immoral influence.”

This, to me, marks a clear shift in the tide against the 1857 Obscene Publications Act. Granted, the decision was in another country, and the defense used a remarkably smart strategy to ensure a case favorable to them, but the United States had been using the British Hicklin Test as a way to determine prosecutable obscenity., and furthermore, the ruling created a precedent that English lawyers could then exploit in their arguments. Ernst succeeded in identifying the weak spot in the armor of the Test, the same spot that its supporters considered strength: its broadening of the 1857 Obscene Publications Act and the attendant results was not the intention of the original law.

Morris Ernst (Wikimedia)

Four years later, in 1933, Ernst would go on to defend Joyce’s Ulysses before the Supreme Court and succeed there as well, opening the way for its publication in England a few years later, in 1936. The Well of Loneliness was freely published in England in 1946. The 1857 Obscene Publications Act would be revised in 1959 to include the author’s right to argue for literary merit along with the requirement that the entire work be considered, not just individual sections. Even the long-dead ‘pornographer,’ D.H. Lawrence finally got his day in court—Lady Chatterley’s Lover was deemed ‘not obscene’ in 1961. The age of the obscene moderns was over.

Sources

[1] To The Pure — Morris Ernst

[2] The Well of Loneliness — Radclyffe Hall

[3] Bound & Gagged A History of Obscenity in Britain — Alan Travis