Brian M. Watson's Blog

May 10, 2016

NotchesBlog Article

Hey guys,

I recently wrote an article about the SSV/Lord Campbell for Notches, which is the leading history of sexuality online journal.

You can read it here: http://notchesblog.com/2016/05/10/a-p...

The book continues to sell well and I’m still looking for a paper publisher

April 5, 2016

Updates!

Hey folks!

Just wanted to give you a quick update on the fact that I’m sill working on publicity for the book, as well as paperback copies. Plus, I might have some more exciting news coming.

I thought I would give you a heads-up about all the places you can download the book from– Amazon.com in their Kindle format here, or Smashwords in any number of formats here, or finally in the Barnes and Noble/Nook Store in their epub format here.

If you wanted to write a review on any of those three websites, it would be greatly appreciated.

Happy spring to you all!

Brian

March 19, 2016

AMA on Reddit Today at 8:30AM EST

Hello folks!

I’ll be doing an AMA on Reddit around 8:30AM this morning. Come by and ask me anything!

I’ll post the link here when it goes live!

Here it is!: https://www.reddit.com/r/IAmA/comment...

Cheers!

Brian

March 7, 2016

Kindle Book Available on Amazon!!

Hey folks,

Just wanted to give you a heads up that the Kindle version has gone live–you can get your copy here. Another update when Smashwords and Nook go live, and a word on when I’m going to do interviews. Going to Iceland this week to visit the World Penis Museum, wish me luck!

Thanks for reading with me,

Brian

February 24, 2016

Book Cover and Details!

Hey y’all!

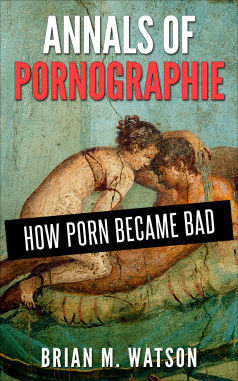

I’ve been busy finalizing the book cover and some details on the book release. The book will be released on March 5th, 2016. I will have it available on Amazon, Nook/Barnes&Nobles, iBooks, and Kobo hopefully. I’m also aiming to set up a AMA–Ask Me Anything–on Reddit for the book release. I’m pondering setting up a podcast after the release if everything goes well. Anyhow, I figured I’d share the cover with y’all first, so here it is:

Looking forward to seeing you guys on the other side, thanks for all the love and attention the past year.

–Brian

January 6, 2016

Greetings to #twitterstorians and American Historical Association Attendees!

Hello there!

This post is to welcome the new visitors to my blog over the next three days. I will be visiting the American Historical Association to present as a part of Reddit’s AskHistorians Community. Here is a link to our presentation.

If you’re reading this blog as a new reader at any time in the next three days, there’s a good chance I met you in person and gave you my card! I would like to welcome you to my blog–which is really the rough draft of my first book, expected in March or April of this year. I would invite you to start at the very beginning of this blog/book as to make better sense of what is going on, but here is a link to some of my most popular posts/series:

On Pietro Aretino, the ‘father’ of pornography: Pietro Aretino: The ‘Father’ of Pornography. Part I: Origins and Inspiration

On marriage and the ‘invention of privacy:’ Sex Behind Closed Doors: Marriage, and the Invention of Privacy

On Edmund Curll: The ‘first’ Hugh Hefner: Edmund Curll, the First Hugh Hefner. A Pyratical Pornographic Publisher.

On the shifts of marriage and privacy in the 17th and 18th centuries: Bless with one hand and curse with the other: How Marriage for Love became Good and Masturbation became Bad

Cheers!

Dirty, Filthy Images: Pornographic Photography and Film

I’ve not forgotten about this or ceased to exist, I’ve just been working on the actual book copy of this blog. I am leaning towards publication in March or April, after finalizing editing. More details to come soon.

As regular readers of this blog have no doubt noticed, I have largely focused thus far on books, engravings and erotic artwork. This might be surprising for a blog that claims to be about the history of pornography and obscenity, especially because when people think ‘porn’ they’re most likely to think about dirty pictures or hardcore movies, or one of the thousand of pornographic websites on the internet. The first things to come to your mind aren’t usually by the Italian father of pornography, Pietro Aretino, or the poetry of libertine English Earls, or even the dark philosophies of the Marquis de Sade. No, the first things that come to your mind are more likely to be Playboy Magazine, or the more famous websites such as pornhub.com or kink.com, or even a personal experience with pornographic material.

Part of the reason we have spent so much time in focusing on history of the book, or on erotic artwork/engravings is, as I said at the beginning of this blog, pornography has a longer history than we usually assume it does. Roughly, this blog runs (and will run) from the years 1450-1950, from the Renaissance to the Cold War. It is a long period of history, that covers everything from the Reformation to the English and French Revolutions, and, in all honesty, the rise of photography and videography comes at the tail end of that period–the first (surviving) erotic image is from 1839, and the first (vaguely) erotic video by 1894, and the first forthrightly pornographic one not until 1908 (all of these below the fold). This is one reason that I have not covered photography or film.

The other reason, the major one, is that context matters. As I have repeatedly commented throughout this blog, there is no pornography without obscenity, no obscenity without erotica. In the beginning, the first recognizably pornographic works combined social, religious, and political critique and sometimes educational information along with erotic/obscene titillation in order to create a product that our modern eyes wouldn’t always see as pornography (such as Merryland or disguised medical pornography). It took several important court cases and a pair of reformation societies along with a major Obscene Publications Act to actually create the legal and cultural concept of pornography. Even the word,’pornography,’ dates as late as 1857. So the purpose of this entry is to address the history of visual (photographic and film) pornography and how it fits into the history of pornography as a whole. So follow me below the fold for more.

Please note that most of the images below the field are definitely not safe for work.

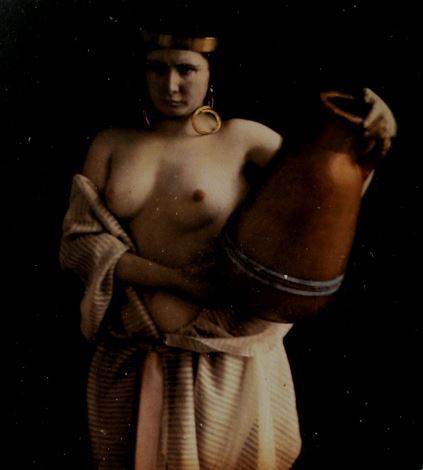

Here’s a selection of erotic dagguerrotypes:

![A collection of Erotic Daguerreotypes from the Uwe Scheid Collection. [1000 Nudes]](https://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/hostedimages/1457112119i/18321521.jpg)

![A collection of Erotic Daguerreotypes from the Uwe Scheid Collection. [1000 Nudes]](https://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/hostedimages/1457112119i/18321522.jpg)

![A collection of Erotic Daguerreotypes from the Uwe Scheid Collection. [1000 Nudes]](https://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/hostedimages/1457112119i/18321523.jpg)

![A collection of Erotic Daguerreotypes from the Uwe Scheid Collection. [1000 Nudes]](https://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/hostedimages/1457112119i/18321524.jpg)

![A collection of Erotic Daguerreotypes from the Uwe Scheid Collection. [1000 Nudes]](https://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/hostedimages/1457112119i/18321525.jpg)

![A collection of Erotic Daguerreotypes from the Uwe Scheid Collection. [1000 Nudes]](https://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/hostedimages/1457112119i/18321526.jpg)

[image error]

<>A collection of Erotic Daguerreotypes from the Uwe Scheid Collection. [1000 Nudes]

As is commonly known, the first major breakthrough in photographic technology originated from the experiments of Louis Daguerre, who invented the process known as daguerreotype, and whose technology was given to the world by the French nation in 1839. Daguerreotypes were a major breakthrough because they allowed a photographic exposure to be taken in a matter of minutes, versus the hours of exposure that used to be required. To make a daguerreotype, early photographers took a cleaned and polished copper plate and covered it with a thin layer of silver iodide—by candlelight, in order to avoid any exposure to light. The image is revealed by exposing it to mercury vapors (very dangerous and nauseating), and then washing it in salty water. This labor-intensive process, combined with the high cost of the materials, made daguerreotypes only available for the financially well-off. It was not until 1853 when the Englishman Fredrick Scott Archer’s negative on glass process allowed printing on paper in unlimited amounts.

As proof of my statement that literature provided the model and context for pornography, erotic photography followed the same process as erotic literature. In the beginning, photographs were expensive (as much as a week’s salary for the average person), and their high cost limited the purchasers to the upper-classes. The first publishers and connoisseurs—Hans-Michael Koetzle notes in 1000 Nudes: A History of Erotic Photography—saw this as a good thing, as the prices kept the number of customers to a manageable level, and confined to “social classes respected for their moral integrity and ethical stability.” The improved technology which allowed mass printing and lowered costs was what caused things to become, “‘problematic’ in the pleasure-dampening and prudish Victorian sense.”

But when the process became easier, and photography became more widespread and more of an industrial process, then the moral outcry and demands for regulation began. By the 1860s, paper photographs were being sold by hawkers or booksellers in London’s Holywell Street or in the Grands Boulevards district of Paris. As Alexander Dupoy puts it in his Erotic Art Photography:

The moral question of circulation to the general public was not a problem when it only concerned the daguerreotypes, as the excessive cost ensured a limited distribution to the elite. It now became a problem, as it was possible for every soldier, schoolboy, young man or even young woman to acquire or have access to a licentious image, even if the image was academic. The mid-nineteenth century was a time of great confusion between moral order and artistic aestheticism.

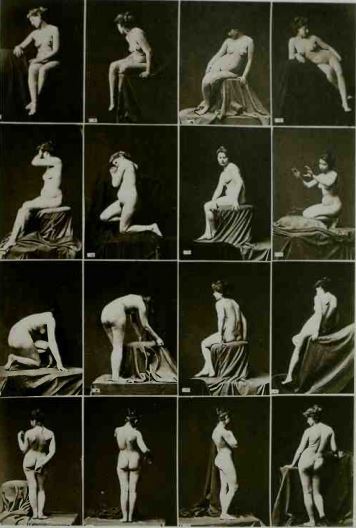

The subjects of the first images were of landscapes or objects—it was difficult to photograph nudes or people because it took several minutes to take the picture, and people had a tendency of moving, especially if said people were having sex. Regardless, where there is a will, there is a way. According to Alexandre Dupouy’s Erotic Photography, a certain optician named Noël-Marie Paimal Lebours claimed to have taken the first nude photograph by 1841 (I could not find a copy of it however!). Hilariously enough, when the first commercial photographs went on sale in France, they were available from the offices of opticians, and in the salons of high-end art dealers—not in shady backstreet alleyways (that would come later). The original nude photography was almost like a painting would be done. As Dupouy notes:

They mimicked artists and painters by making pastiches of their compositions and the use of accessories, including draping, columns and fabric. In fact, most of the precursors of photography came directly from painting. The interconnection between the two processes seemed obvious: photographers were inspired by painters, and painters made use of photography. With photography, artists no longer had to put up with models who either did not turn up or were late.

Here’s a selection of some of these earliest ‘artist studies:’

<>A selection of erotic 'artist's studies' from the Uwe Schied Collection. Note the artistic posing and drapery of each picture.

But this does not mean that all erotic photographs were sweet and innocent photographs; it only look seven years from the announcement of the technology to the first commercially available daguerreotype of people having sex!

As the French were the first to pioneer and master daguerreotypes and photography, Paris became the center of the trade in erotic and obscene images, just as it had once served as the center for erotic and obscene books. In 1848, only 13 studios existed in all of Paris, but by 1860, there were over 400. All of them claimed to be reputable joints that only took pictures of individuals and families, but in fact, most of them traded and profited from the sale of nude images to any customer that had the money. The lewd pictures were also sold near train stations by hawkers, and in the streets of London, Paris, Amsterdam, Philadelphia, New York, other European and American cities, and were also sent via mail to customers. All of these activities caused the Societies for the Suppression of Vice in England and America to begin targeting and prosecuting the sellers, along with their decades-long fight against obscene literature. A police report from Paris illustrates how much the trade had boomed:

1850s records [show] that exactly 60 photographs had been seized. Ten years later, thousands of Stereo cards had been confiscated. And in 1875 over 130,000 photographs with “lewd” motifs, as well as 5,000 negatives, are said to have fallen into the hands of the London police. The more professional the medium became, the more erotic views came on the market.

The prosecutions began. It seems the first lucky individual prosecuted for erotic photography was one Félix Moulin, about whom not much is known. He was prosecuted in 1851 and sentenced to one month in prison and a fine of 100 francs. However, the fines on female models was far worse—in 1857, four women were sentenced to six months in prison on top of a hundred franc fine.

About this time, in the 1900s, film technology began to take off. As with photography, the technology was pioneered first by a Frenchman, named Louis Le Prince, and then improved by the American inventor Thomas Edison. The technology was rather basic in the beginning, just a strip of pictures printed on film and then rotated in a loop with a high-speed shutter to create the illusion of movement. In 1894 Edison’s studio recorded a vaguely erotic short, titled Carmencita, which featured a Spanish dancer who twirled and posed on film for the first time. The short was considered scandalous in some places because Carmencita’s underwear and legs could be seen in the film. A couple of years later, in 1896, the same studio recorded The May Irwin Kiss, an 18 second film of a Victorian couple kissing (in an incredibly awkward and forced manner). According to Maximillien De Lafayette, this scene in particular caused uproar among newspaper editorials, cries for censorship from the Roman Catholic Church, and calls for prosecution—although these calls do not seem like they were followed up on.

The first hardcore pornographic movie that survives.

The first hard-core pornographic film (that survives) is a 1908 French film, A L’Ecu d’Or ou la Bonne Auberge (At the Golden Crown or The Right Inn. The word ‘l’ecu’ literally means ‘crown’ but is also a euphemism for a vagina). This film can actually be found online. The film begins with a hotel maid cleaning up a room with a (recently-invented) vacuum cleaner when the screen announces, in silent movie format, that she has “une riche idee” [a good idea]. She begins to use the sucking end of the (presumably off) vacuum as a dildo, until she is walked in on by the husband and wife whose room she is supposed to be cleaning. The pair drag her off of the bed and the trio all begin to take their clothes off. The group all fall into the bed, there is a scene of oral sex, a scene of 69-ing, face-sitting, intercourse, and then the four minute long movie ends. This movie was never made available to the public, of course, and seems like it was recorded by a private company or group for a small audience, which would have limited its audience and kept it out of the public eye.

As with photography before it, and books before that, film eventually became cheaper and more widespread, began appearing in the alleyways and under the counter at stores, and eventually lead to arrests, prosecution and jail time. The Czech movie Ecstasy (1933), for example, featured scenes of nudity, and perhaps the first female orgasm shown in a major theatrical release. The scandal of these scenes lead to cries for the seizing and banning of the offensive material, and lead to the Hayes Code in the United States, which successfully banned erotic material from Hollywood movies for the next 30 years. Full freedom of pornographic expression was not available until 1988’s California v. Freeman, which effectively legalized hardcore pornography.

Sources:

[1] 1000 Nudes: A History of Erotic Photography — Hans-Michael Koetzle

[2] Erotic Art Photography — Alexandre Dupouy

[3] The Erotic Engine: How Pornography has Powered Mass Communication — Patchen Barss

December 5, 2015

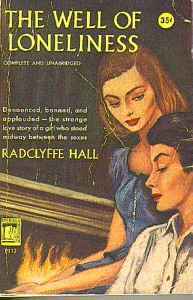

‘He has left usforsaken!’ The Well of Lonliness and the Obscene Publications Act

1951 Edition of Well of Lonliness

At the same time Lawrence was castigating ‘grey elderly ones,’ in his pamphlet, another trial over obscene literature was taking place, one that holds augurs for the mid-century shift that produced the 1959 obscenity law—the 1928 trial over Radclyffe Hall’s The Well of Loneliness. Like Maurice and The Rainbow, Hall’s novel is a coming of age story that documents a characters childhood and adulthood. Unlike Lawrence, Hall was not interested in frank depiction and description of sexuality. In fact, the most ‘obscene’ or suggestive line in the novel occurs when the main character kisses another woman “full on the lips, as a lover.”

While Forester was much more cautions and hesitant about publishing a novel that discussed or featured homosexuality, Hall was not reserved at all. Combining Forester’s agenda with Lawrence’s agressive writing style, Hall published the Well of Lonliness in 1928 and almost immediately brought legal trouble on herself and her published. Although it would be easy to propose that it was Hall’s mention of homosexuality brought down official censure, the fact that Virginia Woolf published a book (Orlando) in the same year and on the same topic means that is not likely. The difference is that Hall treated The Well of Loneliness as a polemic against the British establishment, especially the homophobic attitudes of the time

Radclyffe Hall

The Well of Loneliness tells the story of Stephen Gordon, the daughter—despite the name—of two upper-class English parents, Anna and Sir Philip Gordon. Her masculine name was given to her by her father. When Anna conceives, Sir Philip is struck by “how much he longed for a son” and they take to calling the fetus Stephen. Unfortunately, as the narrator puts it, “’Man proposes—God disposes,’” and Stephen is born a girl. Sir Philip however, “insisted on calling the infant Stephen…[and] was stubborn, as he could be at times over whims.” From a very young age however, Stephen manifests signs of ‘sexual inversion’ as Ellis called it, and “became aware of an urgent necessity to love. She adored her father, but that was quite different… it was other with Collins, the housemaid.” When Stephen becomes infatuated with Collins her father notices and begins to “study his daughter gravely,” reading late at night a book by a certain German, Karl Heinrich Ulrichs—the first sexologist to propose a theory of homosexuality. He is unable to tell his wife of his discovery and:

committed the first cowardly action of his life. . . In his infinite pity for Stephen’s mother, he sinned very deeply and gravely against Stephen, by withholding from that mother his own conviction that her child was not as other children. . . ‘There’s nothing for you to understand,’ he said firmly, but I like you to trust me in all things.

From this passage you can see how Hall uses the characters and the events in the book to pass judgement and critique the culture of England.

Stephen’s first inkling that something might be different about her comes when a friend named Martin confesses his love for her and she “stare[ed] at him in a kind of dumb horror, staring at his eyes that were clouded by desire, while gradually over her colourless face there was spreading an expression of the deepest revulsion—terror and revulsion.” It is only when she falls in love with an older woman, Angela Crossby, and declares it, does the book reach its rhetorical (and obscene) height:

Stephen answered ‘I know that I love you, and that nothing else matters in the world’. . .all that [Angela] was, and all that she had been and would be again, perhaps even to-morrow, was fused at that moment into one mighty impulse, one imperative need, and that need was Stephen. Stephen’s need was now hers, by sheer force of its blind and uncompromising will to appeasement. Then Stephen took Angela into her arms, and she kissed her full on the lips, as a lover.

Still, the idyll does not last, and the discovery of the affair by Stephen’s mother causes her to say “unnatural… this thing you are is a sin against creation.” It is in this moment that Stephen “found her manhood,” and when she discovers her father’s books on sexology, Hall paints a pathetic (in the pathos sense) picture: holding her fathers “old well-worn Bible. [Stephen] demand[ed] a sign from heaven—nothing less than a sign from heaven she demanded. The Bible fell open near the beginning. She read: ‘And the Lord set a mark upon Cain…’ Then Stephen hurled the Bible away.”

The rest of the novel continues more or less in this sense, with Hall creating scenes to show that Stephen is congenitally ‘inverted’ and blameless for her identity. She becomes a novelist, and then serves as an ambulance driver in the War, where she falls in love with another woman named Mary. By the end of the novel, she determines that in order to ‘protect’ Mary, she must ‘martyr’ herself and send Mary away. Her novel ends with a famous appeal that describes the ghosts of all the people she knew

calling her by name, saying… ‘Stephen, Stephen, speak with your God and ask Him why He has left usforsaken!’. . . And now there was only one voice, one demand; her own voice into which those millions had entered. . .’God,’ she gasped, we believe; we have told You we believe. . .We have not denied You, then rise up and defend us. Acknowledge us, oh God, before the whole world. Give us also the right to our existence!’

Hall’s brazenness and forthrightness was something that the British Home Office could not tolerate, especially as her publisher began importing books that had been secretly printed in Paris. Relying on their usual strategy of targeting a publisher and thereby bypassing the danger of a trial about literary merit, the authorities organized an elaborate sting operation to seize all copies of the book in England.

Unlike Lawrence or Ellis, Hall’s publisher had already decided to stand by her and they had organized a massive legal strategy, a trap that the Home Office fall right into. When the publisher was named in the indictment, he used a loophole in the Obscene Publications Act to say that “Miss Radclyffe Hall wished to be heard under section 32 of the Customs Act as ‘another person,’” allowing her to go on trial. She would be able to speak her ‘one voice, one demand.’ Within two weeks she managed to line up the ‘cream’ of the British literary establishment to testify in her favor: Arnold Bennett, T.S. Eliot, E.M. Forster, Julian Huxley, Rose Macaulay, George Bernard Shaw, Lytton Strachey, and Leonard and Virginia Woolf.

Not all of these figures were there enthusiastically—many of them thought that Hall was too daring, too polemical, and risked exposure and scandal to the entire literary world. Woolf commented on this in her letters: “most of our friends are trying to evade the witness box; for reasons you may guess. But they generally put it down to the weak heart of a father, or a cousin who is about to have twins.” Woolf also expressed reservations over Hall and her book: “no one has read her book; or can read it… so our ardour in the case of freedom of speech gradually cools… we are already beginning to wish it unwritten.”

Luckily for Woolf, she would not end up testifying. The defense lawyer opened his case by saying that it was his intention “to call his distinguished witnesses to testify that the book was not obscene, and those who had passed the 1857 Obscene Publications Act never intended it to be used against such a book.” The purpose of the trial became immediately clear—the defeat of the Hicklin definition of obscene literature. Unfortunately, the prosecution had chosen its judge wisely, and the judge had pre-determined that The Well of Loneliness was obscenity, according to the files of the Director for Public Prosecution examined by Alan Travis. Using the powers of the 1857 Act that was under question, Justice Biron declared that he had the right to define obscenity:

The evidence that is being offered me is expert evidence as to whether or not the book is a piece of literature. That is not the point. The book may be a very fine piece of literature and yet be obscene. Art and obscenity are not disassociated. . .I agree it has considerable merits, but that does not prevent it from being obscene, and therefore I shall not admit this expert evidence.

As Woolf put it, “in what cases is evidence allowable? This last, to my relied, was decided against us: we could not be called as experts in obscenity, only in art.” This episode also shows the continuing importance of judges in our story on the history of obscenity. Indeed, much of this story is impossible without them.

With the very purpose of the trial invalidated, Hall’s defense collapsed. They were unable to prove that the book had merit or that the 1857 Obscene Publications Act was being used in the wrong way—the Act itself was being used to suppress the questioning of the Act. When the judge announced his decision a week later, he was “clear that it was lesbianism itself rather than any particular passage of the book that was being condemned… the better an obscene book is written, the greater is the public to whom it is likely to appeal. The more palatable the poison, the more insidious it is.” After an hour of his speech, Hall seemed to try to cry out with the voice at the end of her novel

Miss Radclyffe Hall: ‘I protest, I emphatically protest.’ Sir Charles Biron: ‘I must ask you to be quiet.’

Hall: ‘I am the author of this book—‘

Biron: ‘If you cannot behave yourself in Court I shall have to have you removed.’

Hall: ‘Shame!’

and was silenced. Furthermore, Hall’s appeal was denied and, much to her dejection, all copies of her book were destroyed in England and the Commonwealth countries of Australia, New Zealand, India, South Africa, and Canada.

The 1928 trial of The Well of Loneliness was a formative and important one for England’s literati. Over 40 of them had been present at the trial, and the other 115+ that had been invited no doubt followed the trial closely. In many ways, this would mark the low point for the writers and the high point for the application of the 1857 Obscene Publications Act and its Hicklin Test. The first sign that the tide was shifting was the already-mentioned 1929 symposium on “The ‘Censorship’ of Books” in which several of Hall’s key experts would argue for the need for reform. Ellis, for example noted that “it is said, indeed, that we have no censorship. If that is so, we have what is worse…call it the Inquisition.”

Forster commented that “I consider that the Act, as at present interpreted, is both unfair to writers and against the public interest, but all I can do is indicate [it]… Non-pornographic books, like The Well of Loneliness, ought not to be suppressed.” Woolf herself even contributed, arguing that the law was harmful to England and “even more serious is the effect upon the writer… [he] is uncertain what may or may not be judged as obscene… he will be asked to weaken, to soften, to omit.” The symposium and its arguments represented the first organized effort by writers to argue in public about the law.

Furthermore, Hall’s trial was instructional to American publishers and lawyers, who would learn the lessons of Hall’s trial well. In February of the following year, the American publishers Covici-Friede bought the rights to the book from Knopf, who refused to publish after the British trial. They then hired Morris Ernst as their lawyer, the co-founder of the ACLU and the author of a book on the legal history of obscenity, To The Pure. Ernst and Covici-Friede seem to have learned three things from the first trial:

1) the defense would have to exercise control over how and by whom the book would be seized,

2) the Obscene Publications Act and the Hicklin Test would have to be the central target of the trial, not societal acceptance of lesbianism, and

3) the literary merit of the work would have to be proved and linked to the original intentions of Campbell when writing the 1857 Act.

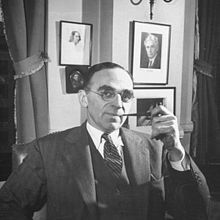

The Logo of the NYSSV

They sent a copy of the first American edition of The Well of Loneliness to the New York Society for the Suppression of Vice, who fell for the bait. Charges of obscenity were brought against the publishers in New York by the NYSSV and attorney general of New York. But, by April of 1929, after reading the book, the judges of the New York Court of Special Sessions cleared the book of any obscenity charges, stating that: “the book in question deals with a special social problem, which, in itself, cannot be said to be in violation of the law unless it is written in such a manner as to make it obscene… and tends to deprave and corrupt minds open to immoral influence.”

This, to me, marks a clear shift in the tide against the 1857 Obscene Publications Act. Granted, the decision was in another country, and the defense used a remarkably smart strategy to ensure a case favorable to them, but the United States had been using the British Hicklin Test as a way to determine prosecutable obscenity., and furthermore, the ruling created a precedent that English lawyers could then exploit in their arguments. Ernst succeeded in identifying the weak spot in the armor of the Test, the same spot that its supporters considered strength: its broadening of the 1857 Obscene Publications Act and the attendant results was not the intention of the original law.

Morris Ernst (Wikimedia)

Four years later, in 1933, Ernst would go on to defend Joyce’s Ulysses before the Supreme Court and succeed there as well, opening the way for its publication in England a few years later, in 1936. The Well of Loneliness was freely published in England in 1946. The 1857 Obscene Publications Act would be revised in 1959 to include the author’s right to argue for literary merit along with the requirement that the entire work be considered, not just individual sections. Even the long-dead ‘pornographer,’ D.H. Lawrence finally got his day in court—Lady Chatterley’s Lover was deemed ‘not obscene’ in 1961. The age of the obscene moderns was over.

Sources

[1] To The Pure — Morris Ernst

[2] The Well of Loneliness — Radclyffe Hall

[3] Bound & Gagged A History of Obscenity in Britain — Alan Travis

November 16, 2015

The Hounding of D.H. Lawrence, Smuthound(?)

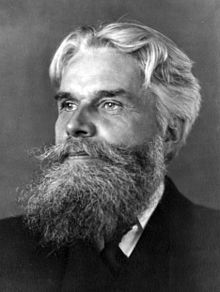

Our topic of conversation today: D.H. Lawrence [Nottingham].

In our last entry, we discussed how the 1857 Obscene Publications Act affected both scientific research and literature in the twentieth century. The result of the OPA and the government’s use of it was sweeping and chilling, and it resulted in most authors and speakers self-censoring or being forced to by their publishers. On the other end of the spectrum was a writer that declared outright contempt for and war upon the Obscene Publications Act: D.H. Lawrence. The near-hounding of Lawrence by the Home Office, newspaper critics, and moral societies from the 1915 burning of The Rainbow to the posthumous trial (1960) of Lady Chatterley’s Lover (1929) was tantamount to decades-long governmental crusade against him. Lawrence responded with a campaign of his own by continuing to write and by targeting English censors with vitriol in poetry such as Nettles (1930) and in pamphlets such as Pornography and Obscenity (1929), which will be examined below.The government became ‘aware’ of Lawrence in 1915, the middle of World War I, where his publication of The Rainbow was immediately met with newspaper criticism of its frank discussion of sex. The Rainbow is a family history of three generations of the Brangwen family, beginning with Tom Brangwen falling in love with Lydia, a Polish refugee. The next section of the book concerns the tumultuous relationship between Lydia’s daughter Anna and her husband Will. However, the vast majority of the book—over three-quarters of it—is focused on Anna and Will’s daughter, Ursula. The Rainbow focuses intently on the subtle politics of relationships, at the expense of all else. This is apparent from the first chapter, “How Tom Brangwen Married a Polish Lady,” to the last pages of the novel, where Ursula dwells on a lost lover. Lawrence’s novel is a study of love, a word that is repeated over a hundred times in it, and seems to crop up every ten pages.

Please be aware that some of the text/images below the fold may be NSFW (not safe for work).

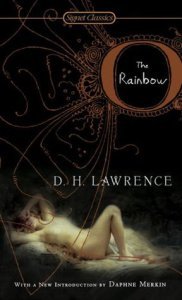

Signet Classics’ edition of The Rainbow

Specifically, The Rainbow focuses on the tensions between love, lust, and power. Both Lydia and Anna ‘give in’ to men and masculine lust, which is described as uncontrollable: when Anna rejects Will’s advances he “became a mad creature, black and electric with fury. The dark storms rose in him, his eyes glowed black and evil,” and he “force[s] his will upon her.” Lydia is erased by Tom, but Anna, who represents a transition from absolute patriarchy, is not completely powerless: when Will had finished “getting his satisfaction of her” she “strikes back,” dashing, goading, harassing him (in her words), until he “recognized her as the enemy.” The tempestuous war between the two of them continues, alternating between intense hostility and overwhelming love, until they are complete strangers to each other. Only then, when they treat each other as equals are they transformed:

He was the sensual male seeing his pleasure, she was the female ready to take hers: but in her own way. . . She was another woman under the instance of a strange man. He was a stranger to her, seeing his own ends. Very good. . .They abandoned in one motion the moral position, each was seeing gratification pure and simple. . .he lived in a passion of sensual discovery with her.

The battle between the pair is essentially a conflict over love and power, over the need for control and dominance in the relationship. Whereas Lydia was essentially controlled and dominated by her husband, Anna and Will, alienated from each other over the course of years, manage to have a rapprochement by finally seeing each other as equals and taking what they want from each other.

If the visceral descriptions were not disturbing to censors, the account of Ursula’s life, which takes up most of the book was undoubtedly so. Representing (to Lawrence) the most important and modern generation in the Brangwen family, Ursula is the first woman who has the freedom to choose between love and power, to control or refuse the masculine lust that is foisted upon her, or even pursue alternate routes. For example, when she begins a relationship with Anton Skrebensky, a British soldier, she does not ‘give in’ to his entreaties or physical goading:

He appropriated her. There was a fierce, white cold passion in her heart. . .like a soft weight upon her, bearing her down. . . but still her body was the subdued, cold, indomitable passion. . . She received all the force of his power. . . She was cold and unmoved as a pillar of salt.

Despite the fact that his “will was set and straining with all its tension,” he is “annihilated” and her pillar of salt “burn[s] and corrod[es]” him. Under a patriarchal system, the two fates for women were supposed to be marriage and reward or whoredom and punishment—Lawrence’s Ursula subverts both of these. When Anton returns from fighting the Boer War years later, the pair end up getting engaged and having sex. However, Ursula abruptly decides that “’I don’t think I want to marry you [Anton]… I don’t want to be with other people’ she said. ‘I want to be like this. I’ll tell you if ever I want to marry you.’” Anton breaks off their engagement, marries another woman, and sails for India, and Ursula finds that she is pregnant. Disaster for the whore seems to loom—but it never manifests, as Ursula miscarries, and then carries on with her life, stronger than before—she becomes the protagonist of Lawrence’s next novel, Women In Love (1920).

Sir William Joynson-Hicks, 1st Viscount Brentford, who made it his life’s goal to hound Lawrence.

On top of Ursula’s subversions and Lawrence’s descriptions, two final nails would drive the coffin shut for a censorship case: Ursula’s lesbian relationship with her teacher, Ms. Iver, and the questioning of Christianity by various characters. Ursula’s relationship with Ms. Iver was not subtle—Lawrence describes it even more openly than some of his heterosexual relationships, and they indeed “become intimate.” Furthermore, both Ms. Inger and Anna question Christianity; Ms. Inger saying that “religions were local [but] Religion was universal. Christianity was a local branch,” and Anna saying “It is impudence to say that Woman was made out of Man’s body, when every man is born of a woman.” Regardless of which particular alerted or disturbed them, the police were quick to obtain a warrant under the 1857 Obscene Publications Act and seize all copies of The Rainbow for destruction. Like Ellis, they targeted the publisher of the novel, Methuen, and forced them to renounce the book and burn all copies. The publisher was not happy as they had attempted to get Lawrence to “moderate the manuscript and he had twice refused.” The case led to a blacklisting of Lawrence in England, its colonies, and America—the Home Office and others would go after his Women in Love, Lady Chatterley’s Lover, and his other novels, poetry and plays—he was even forced to use a pseudonym (Lawrence H. Davidson) on textbooks he wrote, to avoid scrutiny.

Admirably or foolishly, Lawrence never changed his focus or declined an opportunity to attack his censorial adversaries. For example, when he published a book of poetry, Pansies (1928), Scotland Yard demanded that he remove 12 controversial poems or face prosecution, which he did, saying they were “not terribly important bits.” However, using the publicity he secretly printed 500 copies of the original book, with the offending poems added back in, but for ‘private’ publication only. When they had all sold, he announced this through his publisher, who said that “in the event of any action taken, which I do not consider likely, it would have to be proved that the book was likely to fall into the hands of people who were liable to be morally influenced by it.” Lawrence was well-aware of the distinction between the original 1857 Act and the Hicklin Test, and knew he had a good case if it were to go to trial. Indeed, it seems that he deliberately instigated the authorities in hope of this. Unfortunately for Lawrence, the Director of Public Prosecutions was also well-aware of the distinction, and refused to proceed in the issue, even if the Home Office wanted to pursue editions sent overseas.

One of Lawrence’s paintings that were seized.

Lawrence’s name alone seemed to be enough to bring down the police—an exhibition of his paintings in 1929 caused the police to dig up an even earlier act, the 1842 Vagrancy Act, in order to charge the gallery owner, Mr. St. John Hutchinson, with exhibiting indecent prints. When he appeared before the magistrates, Hutchinson argued that “the raid amounted to a new form of censorship. ‘I have not been able to find any case in which serious paintings have

Another Lawrence Painting that was seized.

been brought into a police court and a magistrate has been asked to decide whether they were obscene.’” Whether or not the magistrate was in agreement, he said he would dismiss the case if Hutchinson would agree to pay a fine of five pounds, which he agreed to, not willing to risk further prosecution as Lawrence may have been. The whole episode particularly enraged Lawrence, and he quickly responded to the trial with his landmark pamphlet/essay, Pornography and Obscenity (1929), where he noted that “when the police raided my picture show, they did not in the least know what to take. So they took every picture where the smallest bit of the sex organ of either man or woman showed.”

Pornography and Obscenity serves as a very useful insight into Lawrence’s understandings of sex and sexuality, and his use of them in his novels. He begins the essay by stating “what they [pornography and obscenity] are depends, as usual, entirely on the individual.” Noting that pornography means “the graph of the harlot” and obscene meant “that which might not be represented on stage” he points out the same issue that Lord Lyndhurst did a half-century earlier: “what is obscene to Tom is not obscene to Lucy or Joe.” In Lawrence’s view, it is mob-rule and mob-understanding that decide the obscene “Vox Populi, Vox Dei, don’t you know. If you don’t we’ll let you know it.” But Lawrence suggests a shift for the popular understanding of pornography, because

Cover of Pornography and Obscenity

even I would censor genuine pornography, rigorously. . .what is pornography, after all this? It isn’t sex appeal or sex stimulus in art. It isn’t even a deliberate intention on the part of the artist to arouse or excite sexual feelings. There’s nothing wrong with sexual feelings in themselves, so long as they are straightforward and not sneaking or sly. . .Pornography is the attempt to insult sex, to do dirt on it. This is unpardonable.

The ‘grey elderly ones’ that Lawrence targeted were, in his eyes, responsible for putting dirt on sex and love. As he would say in his Apropos of Lady Chatterley’s Lover: “I want men and women to be able to think sex, fully, completely, honestly, and cleanly. Even if we can’t act sexually to out complete satisfaction, let us at least think sexually, complete and clear.” The police and the censors that called them out were “the grey elderly ones” that “belong[ed] to the last century, the eunuch century… the century that has tried to destroy humanity, the nineteenth century…of purity and the dirty little secret.” Sexuality and its artistic representation, the last barrier in polite conversation and public discourse, was the battleground on which Lawrence fought for the right to express himself.

However, he was repeatedly stymied by a prosecutorial strategy that targeted publishers or gallery owners who were not willing to risk a full trial. As a result, Lawrence was left with an unwarranted reputation as a pornographer and nearly chased out of Britain by the end of WWI. A long period of self-imposed exile compounded by ill health and his death in 1930 left him unable to challenge the reputation in court, and he did not live to see the turning point in his struggle.

Sources:

[1] The Rainbow, D.H. Lawrence

[3] Lady Chatterley’s Lover,D.H. Lawrence

November 8, 2015

Obscenity and Art: How the Obscene Publications Act Hurt Science and Literature

Havelock Ellis, with a magnificent beard.

As is demonstrated by the past two entries on The Romance of Lust, the 1857 Obscene Publications Act did little to nothing to control the rising tide of obscenity and pornography. If you will recall from the earlier entry, Lord Baron Campbell only managed to get the 1857 Act passed by promising that it would apply only and exclusively to “works written for the single purpose of corrupting the morals of youth and of a nature calculated to shock the common feelings of decency in any well-regulated mind,” and that any book that made any pretensions of being literature or art, classic or modern, had nothing to fear from the law.

The title page of The Confessional Unmasked.

The tremendous irony of Campbell’s theater was that less than three decades later “the law would be used against the classical works the Lords had wanted to guard, and especially against current literature.” The shift occurred in 1868, with the Regina v. Hicklin decision. The case concerned a man named Henry Scott, an extreme anti-Catholic, who reprinted an old anti-Catholic pamphlet called The Confessional Unmasked: shewing the depravity of the Romish priesthood, the iniquity of the Confessional, and the questions put to females in confession, which is a ridiculously dry and boring theological pamphlet whose arguments and comments go as far back as the Reformation. I’ll spare you the details, but the sauciest it really gets is when it talks about how priests question women about sex with their husbands, and about how priests seduce women–the same anti-priest story that goes back to Boccaccio or Aretino.

But newly-empowered goverment officials seized the work and ordered it destroyed because it might corrupt a child reading it. Originally Scott was found innocent, because he had just meant to insult Catholics, not to corrupt children, but when the case was appealed to the Queen’s Bench (the highest court), the innocent decision was over turned and Justice Cockburn wrote that any work that could

deprave and corrupt those whose minds are open to such immoral influences, and into whose hands a publication of this sort may fall… [anything that] suggest to the minds of the young of either sex, or even to persons of more advanced years, thoughts of a most impure and libidinous character

was prosecutable obscenity. The Hicklin Test, as it came to be called, widened the definition of obscenity from works written ‘for the sole purpose of corrupting the morals of youth’ to works that ‘deprave and corrupt’ and ‘may fall’ into the hands of anyone with an mind. In other words, it was no longer just the youth that needed to be protected, but the minds of the entire British public. In other words, the intention of the author was irrelevant, all that mattered was protecting the innocence of the public.

Following the Hicklin decision, groups such as the National Vigilance Association (est. 1885) seized on it as a new weapon in their battle “for the enforcement and improvement of the laws for the repression of criminal vice and public immorality.” Utilizing a strategy developed by Anthony Comstock and the American Society for the Suppression of Vice, these groups would purchase copies of books they found obscene and then prosecute the publishers for allowing the book to fall into their hands. Additionally, government authorities, particularly the Home Office (which controlled products that could be imported into England) used the same strategy to target books that were printed on the Continent and then brought into Europe. The Hicklin Test enabled the prosecution of any book found suspect, whether a work of literature such as Emile Zola’s La Terre (prosecuted in 1888), or a medical text that explained sex and contraception such as The Fruits of Philosophy (prosecuted in 1877).With such descriptions as

the exterior orifice commences immediately below [the Mons Veneris]. On each side of this orifice is a prominence continued from the mons veneris, which is largest above and gradually diminishes as it descends. These two prominences are called the Labia Externa, or external lips. Near the latter end of pregnancy they become somewhat enlarged and relaxed, so that they sustain little or no injury during parturition

the latter was not meant to be particularly pornographic. Nor does it seem that the author’s single purpose was to corrupt the morals of youths—in fact, the stated purpose was “not to gratify the idle curiosity of the light-minded. . . [but] for utility in the broad and truly philosophical sense of the term.” This was even recognized at the trial, where the jury noted that they “entirely exonerate the defendant from any corrupt motives in publishing it.” However, the jury held, at the same time, that “we are unanimously of opinion that the book in question is calculated to deprave public morals.” For Justice Cockburn, that was a verdict of guilty.

The jury’s split statement shows the conflict between the intentions of the Obscene Publications Act and its expansion under Hicklin Test. The problem with The Fruits of Philosophy was not its obscenity, but the fact that it explained birth control—its advocacy for onanism was the reason it, was found to deprave public morals.

Title page to the second volume of the Psychology of Sex

This is also illustrated by the prosecution of Havelock Ellis’ second volume of The Psychology of Sex, also known as Sexual Inversion (homosexuality). Ellis specifically says in his introduction that his intention was not to deprave or corrupt anyone:

I had not at first proposed to devote a whole volume to sexual inversion. It may even be that I was inclined to slur it over as an unpleasant subject, and one that it was not wise to enlarge on.

Knowing it was not wise; Ellis went to lengths to make his text scientific, even to the point of publishing it (1896) in German. Nonetheless, when it was translated into English the following year, the work quickly came under fire. The ‘problem’ with Ellis’ work for the Home Office was that he refused to criminalize homosexual relationships, which were highly illegal in England at the time:

I realized that in England, more than in any other country, the law and public opinion combine to place a heavy penal burden and a severe social stigma on the manifestations of an instinct which to those persons who possess it frequently appears natural and normal. It was clear, therefore, that the matter was in special need of elucidation and discussion.

Ellis was not only cautious in his language—he also prepared “an elaborate defense and assembled a team of medical experts to prove the book’s scientific merit.” However, his name did not appear on the indictment—the name of his bookseller did. The bookseller pleaded guilty after an intimidating lecture by the magistrate, and Ellis’ elaborately planned defense never saw the light of day. Unable to have his day in court, he was left powerless and had to publish his books in Paris or the United States. Even then, American authorities were only slightly more lenient, allowing Ellis’ works to be purchased by only by doctors and medical students.

Ellis’ trial was taught lessons to both government prosecutors and authors. The former found a new strategy in targeting publishers and booksellers, and the latter realized that representations of sexuality in any form, especially homosexualiy, was the same thing as painting a target on their chest. For the government, targeting publishers instead of artists allowed them to 1) sidestep the issue of literary/artistic value, 2) publishers were much more likely to ‘put it all on the line’ for the sake of one book or author, and 3) this let them use the Hicklin test as a bludgeon against any work found less than pure. The overall result was that publishers began to require authors to revise their work before publication. Additionally, many authors engaged in self-censorship or complete silencing, to avoid calling attention to themselves.

Maurice by EM Forester

One example of this latter strategy is Maurice (1971), by E.M. Forster. Maurice is a bildungsroman and biography of a gay man, Maurice Hall. The work is far too subtle to be ‘written exclusively for the purpose of corrupting the morals of youth.’ For example, Maurice himself is not aware of his own ‘inversion’ until the second part of the novel, nearly a hundred pages in, and Forster himself noted that Maurice’s puzzlement was deliberate. Regardless, the novel’s focus on his relationships with Clive and then Alec was verboten for the time. The erasure of homosexuals from public discourse is even demonstrated when Maurice visits his family doctor and says that there is something wrong with him: the doctor cannot figure out the issue at all, saying he is clean of any STDs. Maurice himself has to say that he is “an unspeakable of the Oscar Wilde sort,” to which the doctor replies “rubbish, rubbish… Listen to me Maurice, never let that evil hallucination that temptation from the devil occur to you again.” The fact that Forster was already a popular author by the time he wrote Maurice (1913-4), meant that the chance of his work falling into the ‘wrong’ hands was too high. Forester of course, realized this, and did not publish the book during his lifetime. Compounding the problem was that Maurice had a deliberately happy ending—the Terminal Note to Maurice says that:

“A happy ending was imperative. I shouldn’t have bothered to write otherwise! I was determined that in fiction anyway two men should fall in love and remain in it for the ever and ever that fiction allows. . .Happiness is its keynote—which by the way has had an unexpected result: it has made the book more difficult to publish. . .If it ended unhappily, with a lad dangling from a noose or with a suicide pact, all would be well, for there is no pornography or seduction of minors. But the lovers get away unpunished and consequently recommend crime. ”

His deliberacy in its revision and diligence in building a personal archive to contextualize it is evidence that he intended Maurice to eventually be published, in “a Happier Year.”

Forester and Ellis were not the only ones damaged or held back by these laws, but they were two of the biggest names to be. In the next two weeks we will look at how resistance to the Obscene Publications Act gained traction among the upper classes and English writers, and lead us down the road to today’s world.

![Our topic of conversation today: D.H. Lawrence [Nottingham].](https://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/hostedimages/1457112146i/18321541.jpg)