Obscenity and Art: How the Obscene Publications Act Hurt Science and Literature

Havelock Ellis, with a magnificent beard.

As is demonstrated by the past two entries on The Romance of Lust, the 1857 Obscene Publications Act did little to nothing to control the rising tide of obscenity and pornography. If you will recall from the earlier entry, Lord Baron Campbell only managed to get the 1857 Act passed by promising that it would apply only and exclusively to “works written for the single purpose of corrupting the morals of youth and of a nature calculated to shock the common feelings of decency in any well-regulated mind,” and that any book that made any pretensions of being literature or art, classic or modern, had nothing to fear from the law.

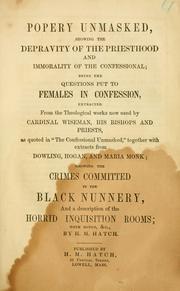

The title page of The Confessional Unmasked.

The tremendous irony of Campbell’s theater was that less than three decades later “the law would be used against the classical works the Lords had wanted to guard, and especially against current literature.” The shift occurred in 1868, with the Regina v. Hicklin decision. The case concerned a man named Henry Scott, an extreme anti-Catholic, who reprinted an old anti-Catholic pamphlet called The Confessional Unmasked: shewing the depravity of the Romish priesthood, the iniquity of the Confessional, and the questions put to females in confession, which is a ridiculously dry and boring theological pamphlet whose arguments and comments go as far back as the Reformation. I’ll spare you the details, but the sauciest it really gets is when it talks about how priests question women about sex with their husbands, and about how priests seduce women–the same anti-priest story that goes back to Boccaccio or Aretino.

But newly-empowered goverment officials seized the work and ordered it destroyed because it might corrupt a child reading it. Originally Scott was found innocent, because he had just meant to insult Catholics, not to corrupt children, but when the case was appealed to the Queen’s Bench (the highest court), the innocent decision was over turned and Justice Cockburn wrote that any work that could

deprave and corrupt those whose minds are open to such immoral influences, and into whose hands a publication of this sort may fall… [anything that] suggest to the minds of the young of either sex, or even to persons of more advanced years, thoughts of a most impure and libidinous character

was prosecutable obscenity. The Hicklin Test, as it came to be called, widened the definition of obscenity from works written ‘for the sole purpose of corrupting the morals of youth’ to works that ‘deprave and corrupt’ and ‘may fall’ into the hands of anyone with an mind. In other words, it was no longer just the youth that needed to be protected, but the minds of the entire British public. In other words, the intention of the author was irrelevant, all that mattered was protecting the innocence of the public.

Following the Hicklin decision, groups such as the National Vigilance Association (est. 1885) seized on it as a new weapon in their battle “for the enforcement and improvement of the laws for the repression of criminal vice and public immorality.” Utilizing a strategy developed by Anthony Comstock and the American Society for the Suppression of Vice, these groups would purchase copies of books they found obscene and then prosecute the publishers for allowing the book to fall into their hands. Additionally, government authorities, particularly the Home Office (which controlled products that could be imported into England) used the same strategy to target books that were printed on the Continent and then brought into Europe. The Hicklin Test enabled the prosecution of any book found suspect, whether a work of literature such as Emile Zola’s La Terre (prosecuted in 1888), or a medical text that explained sex and contraception such as The Fruits of Philosophy (prosecuted in 1877).With such descriptions as

the exterior orifice commences immediately below [the Mons Veneris]. On each side of this orifice is a prominence continued from the mons veneris, which is largest above and gradually diminishes as it descends. These two prominences are called the Labia Externa, or external lips. Near the latter end of pregnancy they become somewhat enlarged and relaxed, so that they sustain little or no injury during parturition

the latter was not meant to be particularly pornographic. Nor does it seem that the author’s single purpose was to corrupt the morals of youths—in fact, the stated purpose was “not to gratify the idle curiosity of the light-minded. . . [but] for utility in the broad and truly philosophical sense of the term.” This was even recognized at the trial, where the jury noted that they “entirely exonerate the defendant from any corrupt motives in publishing it.” However, the jury held, at the same time, that “we are unanimously of opinion that the book in question is calculated to deprave public morals.” For Justice Cockburn, that was a verdict of guilty.

The jury’s split statement shows the conflict between the intentions of the Obscene Publications Act and its expansion under Hicklin Test. The problem with The Fruits of Philosophy was not its obscenity, but the fact that it explained birth control—its advocacy for onanism was the reason it, was found to deprave public morals.

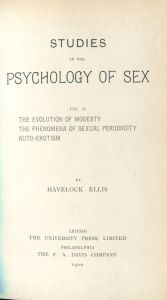

Title page to the second volume of the Psychology of Sex

This is also illustrated by the prosecution of Havelock Ellis’ second volume of The Psychology of Sex, also known as Sexual Inversion (homosexuality). Ellis specifically says in his introduction that his intention was not to deprave or corrupt anyone:

I had not at first proposed to devote a whole volume to sexual inversion. It may even be that I was inclined to slur it over as an unpleasant subject, and one that it was not wise to enlarge on.

Knowing it was not wise; Ellis went to lengths to make his text scientific, even to the point of publishing it (1896) in German. Nonetheless, when it was translated into English the following year, the work quickly came under fire. The ‘problem’ with Ellis’ work for the Home Office was that he refused to criminalize homosexual relationships, which were highly illegal in England at the time:

I realized that in England, more than in any other country, the law and public opinion combine to place a heavy penal burden and a severe social stigma on the manifestations of an instinct which to those persons who possess it frequently appears natural and normal. It was clear, therefore, that the matter was in special need of elucidation and discussion.

Ellis was not only cautious in his language—he also prepared “an elaborate defense and assembled a team of medical experts to prove the book’s scientific merit.” However, his name did not appear on the indictment—the name of his bookseller did. The bookseller pleaded guilty after an intimidating lecture by the magistrate, and Ellis’ elaborately planned defense never saw the light of day. Unable to have his day in court, he was left powerless and had to publish his books in Paris or the United States. Even then, American authorities were only slightly more lenient, allowing Ellis’ works to be purchased by only by doctors and medical students.

Ellis’ trial was taught lessons to both government prosecutors and authors. The former found a new strategy in targeting publishers and booksellers, and the latter realized that representations of sexuality in any form, especially homosexualiy, was the same thing as painting a target on their chest. For the government, targeting publishers instead of artists allowed them to 1) sidestep the issue of literary/artistic value, 2) publishers were much more likely to ‘put it all on the line’ for the sake of one book or author, and 3) this let them use the Hicklin test as a bludgeon against any work found less than pure. The overall result was that publishers began to require authors to revise their work before publication. Additionally, many authors engaged in self-censorship or complete silencing, to avoid calling attention to themselves.

Maurice by EM Forester

One example of this latter strategy is Maurice (1971), by E.M. Forster. Maurice is a bildungsroman and biography of a gay man, Maurice Hall. The work is far too subtle to be ‘written exclusively for the purpose of corrupting the morals of youth.’ For example, Maurice himself is not aware of his own ‘inversion’ until the second part of the novel, nearly a hundred pages in, and Forster himself noted that Maurice’s puzzlement was deliberate. Regardless, the novel’s focus on his relationships with Clive and then Alec was verboten for the time. The erasure of homosexuals from public discourse is even demonstrated when Maurice visits his family doctor and says that there is something wrong with him: the doctor cannot figure out the issue at all, saying he is clean of any STDs. Maurice himself has to say that he is “an unspeakable of the Oscar Wilde sort,” to which the doctor replies “rubbish, rubbish… Listen to me Maurice, never let that evil hallucination that temptation from the devil occur to you again.” The fact that Forster was already a popular author by the time he wrote Maurice (1913-4), meant that the chance of his work falling into the ‘wrong’ hands was too high. Forester of course, realized this, and did not publish the book during his lifetime. Compounding the problem was that Maurice had a deliberately happy ending—the Terminal Note to Maurice says that:

“A happy ending was imperative. I shouldn’t have bothered to write otherwise! I was determined that in fiction anyway two men should fall in love and remain in it for the ever and ever that fiction allows. . .Happiness is its keynote—which by the way has had an unexpected result: it has made the book more difficult to publish. . .If it ended unhappily, with a lad dangling from a noose or with a suicide pact, all would be well, for there is no pornography or seduction of minors. But the lovers get away unpunished and consequently recommend crime. ”

His deliberacy in its revision and diligence in building a personal archive to contextualize it is evidence that he intended Maurice to eventually be published, in “a Happier Year.”

Forester and Ellis were not the only ones damaged or held back by these laws, but they were two of the biggest names to be. In the next two weeks we will look at how resistance to the Obscene Publications Act gained traction among the upper classes and English writers, and lead us down the road to today’s world.