Junk Punch

You have been sucker punched. As a gamer, you've been categorized and used as a negative stereotype to illustrate points about terrible movies. Video games and gamers get a bum rap in film criticism. Film critics seem to like to use video games and the people who play them as a culturally understood idiom. This practice makes the critics look as bad as what they might be criticizing.

You have been sucker punched. As a gamer, you've been categorized and used as a negative stereotype to illustrate points about terrible movies. Video games and gamers get a bum rap in film criticism. Film critics seem to like to use video games and the people who play them as a culturally understood idiom. This practice makes the critics look as bad as what they might be criticizing.

Roger Ebert, with his starkly ignorant opinion of video games as art, might have brought this mistreatment to a head in popular media. This lack of actual cultural awareness has been around for a long time, however, with film critics decrying just about anything that's based on a video game or seems gamish. The trend degenerates from there, with critics using the term "video game" to condemn crappy adventure movies, as well as the term "gamer" to refer to insipid consumers of such dreck. This sort of condescension is a refuge only of someone who can't come up with a meaningful metaphor and, therefore, takes the lazy route of uninformed comparison.

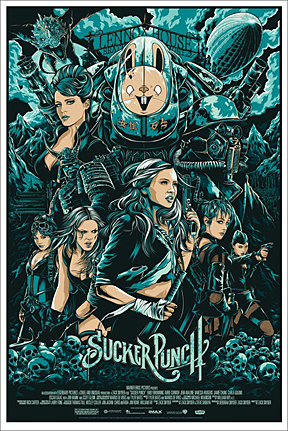

Each supercilious game-movie association, like those that appear most recently in criticism on Sucker Punch, builds on social assumptions that go beyond cliché into plain falsehood. (Full disclosure: I have not seen Sucker Punch, and that fact is irrelevant to this essay.) Some game comparisons are bound to be apt, given the nature of Sucker Punch, its creator (Zack Snyder), and his history. James Berardinelli (Reelviews) says, "As each of these tasks is performed, we are catapulted into bizarre video game-inspired scenarios in which a goal must be achieved." Other critics, such as Lisa Schwarzbaum (Entertainment Weekly), make similar proper comparisons. But the untrue notions of other critics include poor conjecture about what video games are like and what people who play them are like. Such critics lump every game and gamer into a category that likely disappeared, if it ever truly existed, when these critics were "pimply" and "adolescent"—as the Chicago Tribune mentions about some gamers. The marginalized geek exists much more commonly today as a straw man than a real person. Gamers of today are, instead, a diverse folk.

The lumping in doesn't stop with gamers, though. A.O. Scott (New York Times) lumps "video game platforms" among the materials, including drugs, you might need to construct Sucker Punch yourself. He also describes Babydoll and her cohorts, the central figures of Sucker Punch, as video game "avatars" and suggests that Scott Pilgrim vs. the World used "game logic" better as part of its narrative. Unfortunately for his mental construct, video games, their platforms, and their avatars are not all alike. Neither is game logic something that has a consistent definition. (Scott Pilgrim uses comic book methods more than video game ones, but the streams cross enough in modern expression that the point might be moot.) Further, good video games, especially good narrative games, are not cultural equivalents to poorly written or pandering action, fantasy, or sci-fi movies. The tendency for Hollywood to make bad movies based on toy and game intellectual property doesn't allow for a critical license to reverse the relationship. Bad movies have been made from good games. Bad games have been made from good movies. The gamut extends in both directions, with an awful lot of just plain mediocre filling its creamy center.

In a similar center, gamers are not all alike. John Anderson (Wall Street Journal) wrote, "The action sequences are interminable, the acting is a joke, but Sucker Punch is a movie for people who prefer video games and who may be playing them during the movie." Tom Charity (CNN) starts his negative piece with, "Zack Snyder evidently had an awesome idea for a video game." He sums up by saying the movie is "Schlock treatment for comatose gamers . . ." The implicit assumption, the condescension, here is that gamers not only have no taste, perhaps not even the capability of conscious discrimination that could lead to taste, but they also have no attention span. Michael Phillips (Chicago Tribune) says, "Each time the female protagonist goes into her bump-and-grind, the routine is depicted as a video gamer's fantasy of violent combat against zombie Germans in World War I, or cyborgs, or dragons." Which video gamer? Who is he talking about? He's talking about his own stereotype, or what he imagines to be the archetypal gamer.

In a similar center, gamers are not all alike. John Anderson (Wall Street Journal) wrote, "The action sequences are interminable, the acting is a joke, but Sucker Punch is a movie for people who prefer video games and who may be playing them during the movie." Tom Charity (CNN) starts his negative piece with, "Zack Snyder evidently had an awesome idea for a video game." He sums up by saying the movie is "Schlock treatment for comatose gamers . . ." The implicit assumption, the condescension, here is that gamers not only have no taste, perhaps not even the capability of conscious discrimination that could lead to taste, but they also have no attention span. Michael Phillips (Chicago Tribune) says, "Each time the female protagonist goes into her bump-and-grind, the routine is depicted as a video gamer's fantasy of violent combat against zombie Germans in World War I, or cyborgs, or dragons." Which video gamer? Who is he talking about? He's talking about his own stereotype, or what he imagines to be the archetypal gamer.

This is akin to claiming poorly done romantic dramas are exactly like all romance genre fiction—a wide field with varying degrees of writing, some very good—implying that all such fiction is ill conceived and poorly executed from a storytelling standpoint. It goes further, like suggesting such "schlock" is only for 50-something spinsters who live romance vicariously through books. (My wife reads a little romance fiction.) It's similar to marginalizing fantasy genre fiction, relegating all such writing to the realm of B-movie fantasy "schlock" and the fodder to the "Dungeons & Dragons crowd" (1), meaning, really, dateless, basement-dwelling troglodytes who are best at intellectual masturbation. It's basing opinion on popular myth.

A. O. Scott has an impressive background in literature and criticism of storytelling. John Anderson is a respected critic of film who has a long list of impressive publications and associations. Michael Phillips is similar in reputation, and is even a host of the show At the Movies. (Once Siskel and Ebert and The Movies. Phillips filled in for Ebert for a long time, too.) A number of critics have similar backgrounds in literature or film, or both, and they're respected in their field. I'm forced, however, to wonder why they don't stick to their areas of expertise and, instead, resort to drawing tired analogies about something they, by the tone of their statements, obviously don't know enough but assume a lot about. Their remarks are as inappropriate and ill informed as I would be if I insinuated their mythmaking stems from most of them being born in the 60s or earlier. It doesn't.

This diatribe might seem to be rooted in my taking personal offense at the hollow categorization of games and gamers. But this isn't about being affronted. I'm not insulted. These writers have it wrong about games and gamers, and to be truly offended, a little part of you has to believe the offender is right. I don't believe the critics are correct. I believe they've let us down by making false comparisons and weak arguments based on stereotype and conjecture, revealing more about their own disdain for certain cultural elements, or willingness to appear disdainful, than their knowledge about games and movies, and game movies. That is, they failed to do their jobs.

(1) Michael Goldfarb (John McCain 2008 campaign) shows similar myth buy-in, saying back then, "It may be typical of the pro-Obama Dungeons & Dragons crowd to disparage a fellow countryman's memory of war from the comfort of mom's basement, but most Americans have the humility and gratitude to respect and learn from the memories of men who suffered on behalf of others." He later apologized, "If my comments caused any harm or hurt to the hard working Americans who play Dungeons & Dragons, I apologize. This campaign is committed to increasing the strength, constitution, dexterity, intelligence, wisdom, and charisma scores of every American." Wired referred to the gaff as a "resort to '80s-era cultural stereotypes . . ." going on to say, " . . . once McCain masters the internet, we're confident he'll contemporize and start bashing video gamers instead." I'd have stuck with the first statement.

(1) Michael Goldfarb (John McCain 2008 campaign) shows similar myth buy-in, saying back then, "It may be typical of the pro-Obama Dungeons & Dragons crowd to disparage a fellow countryman's memory of war from the comfort of mom's basement, but most Americans have the humility and gratitude to respect and learn from the memories of men who suffered on behalf of others." He later apologized, "If my comments caused any harm or hurt to the hard working Americans who play Dungeons & Dragons, I apologize. This campaign is committed to increasing the strength, constitution, dexterity, intelligence, wisdom, and charisma scores of every American." Wired referred to the gaff as a "resort to '80s-era cultural stereotypes . . ." going on to say, " . . . once McCain masters the internet, we're confident he'll contemporize and start bashing video gamers instead." I'd have stuck with the first statement.

Chris Sims's Blog

- Chris Sims's profile

- 22 followers