Adventure & Service

I've always been captivated by acts of derring-do, by the exploits of adventurous men and women. Especially women who blazed a trail (I know, I use that term a lot) in lands that were supposedly inhospitable to the fairer sex. From Isabella Bird, to the likes of Gertrude Bell, Amelia Earhart, Amy Johnson and Beryl Markham (I listened to the audio version of West With The Night and was torn between trying to make the story last and consuming the whole thing without a break). There are adventurers who have caused me to question their sanity. While reading Into Thin Air, the story of disaster on Mt. Everest, I was left wondering if the mountaineers who risked their lives in freezing – really freezing – conditions were not all a bit unhinged or, indeed, stark raving bonkers. However, as the orthopedic surgeon said to me a day before he operated on my crushed shoulder and badly broken arm (which looked like a very long eggplant at the time), after I'd asked him if I would ever ride again, "We all live with our own level of risk, Jackie." He also said that no one in his family was allowed to have anything to do with horses or motorbikes. Let that be a warning to you.

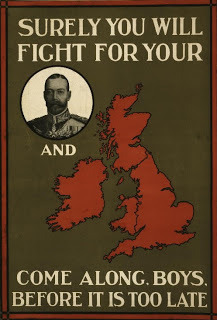

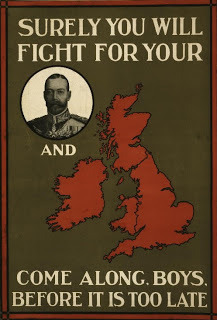

When war broke out in 1914, many of those young men and women who enlisted for service could think no further than the adventure it might offer – the same thing happens even today. They say that wars are fought by the young because they haven't a sense of their own mortality. Enlistment numbers dropped dramatically following the Spring Offensive 1915, when the daily lists of the dead and missing were published, and were growing longer by the day – it had suddenly hit home that going to war could lead you to lose your life.

Many of those who initially rushed to sign up had never been further than the boundary of their village, or town, and had known few people outside their neighbors and, later, those they worked with. Going to war was to be the big adventure. Which brings me to two women who immediately saw the opportunity to blend adventure with service: Elsie Knocker and Maire Chisholm, who, arguably, became the most famous women of the Great War, as news of their courage reached Britain and, indeed, the rest of the world. Here's a potted version of their story:At the outset of war, Elsie, 30, a trained nurse, was divorced and the single mother of a young son, and Maire, 18, hailed from Scotland. It was their love of motorbikes that brought them together, when they met at a motorcycle club in Bournemouth in southern England, where they raced in rallies between 1912 and 1914. Within a month of war breaking out in August 1914, they had roared off to London on their motorbikes to "do their bit." Initially they volunteered for the Women's Emergency Corps, where they became dispatch riders – causing something of a scandal with their masculine breeches, leather jackets and boots. That didn't last long, because just a month later they were in Belgium driving ambulances, taking wounded soldiers from the front lines to the distant military hospitals – while at the same time dodging sniper fire and bombardment while retrieving the grievously wounded from the battlefield. They worked all hours at the hospital treating burns, dysentery, gas-gangrene and shell-shock.

They realized that many of the soldiers were dying of their wounds due to the long journey, so they set up a medical post close more or less on the front line. Aided by Lady Dorothy Fielding, daughter of the Earl of Denbigh, and a young American nurse, Helen Gleason, they fought to save men – and they fought the British Military Establishment, who were determined to "put these women in their place" and shut down the post. Two men helped them stay to do the work they knew was essential to saving lives: Arthur Gleason, Helen's husband, who discovered the shocking extent of the British and French casualties, and Baron Harold de T'Serclaes, who had fallen in love with Elsie.

But just consider their conditions: Their working area was a cellar under a ruined house, with ceilings less than six feet high – this is where they lived, worked, cooked meals and tended to the wounded. They rose at dawn each day and made up hot drinks in buckets, which they took to soldiers on the front line, walking through waist-high mud on the way. They slept on straw, and such was the level of contamination due to the shelling and death, that water had to be shipped from England and then boiled. When the fighting was a at it's most fierce, they slept in their clothes and could not even bathe for weeks. It was reported that at one point Mairi had to be cut from her undergarments after first soaking them, so that her skin would not be removed at the same time. And this was their life, in the town of Pervyse, for three and a half years.

[image error]

Elsie and Mairi became known as the "Angels of Pervyse" as news of their work spread overseas. Apparently, one London newspaper trumpeted their work with the headline, "Sandbags Instead of Handbags!" The King of Belgium awarded them medals that entitled them to be saluted by all soldiers.The two women had to return to the UK when they were almost killed in the shelling, and were poisoned in an arsenic gas attack.You would have thought that there would be a statue somewhere in Britain to honor Elsie Knocker and Mairi Chisholm, wouldn't you? But there isn't, sadly. However, a couple of years ago these daring, brave women received some of the recognition they deserved, albeit long after they died, when Dr. Diane Atkinson published her book, "Elsie and Mairi Go To War: Two Extraordinary Women on the Western Front."

I'm not sure this is the adventure I would have chosen, but it's an inspiring story. Adventure combined with service is a compelling proposition.Who are your favorite adventurers? Who has inspired you with their exploits – and acts of derring-do – far from home? And what would be your dream adventure, if you had the opportunity to make it happen? I have a spare copy of Diane Atkinson's book about Elsie & Mairi to send to the writer of a comment left in response to one or all of those questions (the winner be chosen at random by an independent observer, probably my Mum as I'm flying to the UK this week and she'll have a chance to look at the blog). If you leave a comment, please make sure I have a way of getting in touch with you – you can email me at jacquelinewinspear@gmail.com.There's also a novel that tells of their exploits in a story, however, I have not read that book, but thought you might like to know about it: Angels in Flanders by Jean-Pierre Isbouts.

Next time: Another – and much funnier – Dickens.

When war broke out in 1914, many of those young men and women who enlisted for service could think no further than the adventure it might offer – the same thing happens even today. They say that wars are fought by the young because they haven't a sense of their own mortality. Enlistment numbers dropped dramatically following the Spring Offensive 1915, when the daily lists of the dead and missing were published, and were growing longer by the day – it had suddenly hit home that going to war could lead you to lose your life.

Many of those who initially rushed to sign up had never been further than the boundary of their village, or town, and had known few people outside their neighbors and, later, those they worked with. Going to war was to be the big adventure. Which brings me to two women who immediately saw the opportunity to blend adventure with service: Elsie Knocker and Maire Chisholm, who, arguably, became the most famous women of the Great War, as news of their courage reached Britain and, indeed, the rest of the world. Here's a potted version of their story:At the outset of war, Elsie, 30, a trained nurse, was divorced and the single mother of a young son, and Maire, 18, hailed from Scotland. It was their love of motorbikes that brought them together, when they met at a motorcycle club in Bournemouth in southern England, where they raced in rallies between 1912 and 1914. Within a month of war breaking out in August 1914, they had roared off to London on their motorbikes to "do their bit." Initially they volunteered for the Women's Emergency Corps, where they became dispatch riders – causing something of a scandal with their masculine breeches, leather jackets and boots. That didn't last long, because just a month later they were in Belgium driving ambulances, taking wounded soldiers from the front lines to the distant military hospitals – while at the same time dodging sniper fire and bombardment while retrieving the grievously wounded from the battlefield. They worked all hours at the hospital treating burns, dysentery, gas-gangrene and shell-shock.

They realized that many of the soldiers were dying of their wounds due to the long journey, so they set up a medical post close more or less on the front line. Aided by Lady Dorothy Fielding, daughter of the Earl of Denbigh, and a young American nurse, Helen Gleason, they fought to save men – and they fought the British Military Establishment, who were determined to "put these women in their place" and shut down the post. Two men helped them stay to do the work they knew was essential to saving lives: Arthur Gleason, Helen's husband, who discovered the shocking extent of the British and French casualties, and Baron Harold de T'Serclaes, who had fallen in love with Elsie.

But just consider their conditions: Their working area was a cellar under a ruined house, with ceilings less than six feet high – this is where they lived, worked, cooked meals and tended to the wounded. They rose at dawn each day and made up hot drinks in buckets, which they took to soldiers on the front line, walking through waist-high mud on the way. They slept on straw, and such was the level of contamination due to the shelling and death, that water had to be shipped from England and then boiled. When the fighting was a at it's most fierce, they slept in their clothes and could not even bathe for weeks. It was reported that at one point Mairi had to be cut from her undergarments after first soaking them, so that her skin would not be removed at the same time. And this was their life, in the town of Pervyse, for three and a half years.

[image error]

Elsie and Mairi became known as the "Angels of Pervyse" as news of their work spread overseas. Apparently, one London newspaper trumpeted their work with the headline, "Sandbags Instead of Handbags!" The King of Belgium awarded them medals that entitled them to be saluted by all soldiers.The two women had to return to the UK when they were almost killed in the shelling, and were poisoned in an arsenic gas attack.You would have thought that there would be a statue somewhere in Britain to honor Elsie Knocker and Mairi Chisholm, wouldn't you? But there isn't, sadly. However, a couple of years ago these daring, brave women received some of the recognition they deserved, albeit long after they died, when Dr. Diane Atkinson published her book, "Elsie and Mairi Go To War: Two Extraordinary Women on the Western Front."

I'm not sure this is the adventure I would have chosen, but it's an inspiring story. Adventure combined with service is a compelling proposition.Who are your favorite adventurers? Who has inspired you with their exploits – and acts of derring-do – far from home? And what would be your dream adventure, if you had the opportunity to make it happen? I have a spare copy of Diane Atkinson's book about Elsie & Mairi to send to the writer of a comment left in response to one or all of those questions (the winner be chosen at random by an independent observer, probably my Mum as I'm flying to the UK this week and she'll have a chance to look at the blog). If you leave a comment, please make sure I have a way of getting in touch with you – you can email me at jacquelinewinspear@gmail.com.There's also a novel that tells of their exploits in a story, however, I have not read that book, but thought you might like to know about it: Angels in Flanders by Jean-Pierre Isbouts.

Next time: Another – and much funnier – Dickens.

Published on October 24, 2011 09:37

date newest »

newest »

newest »

newest »

message 1:

by

wonderwomand

(new)

Mar 09, 2016 12:52PM

I was reminded of one of your Maisie Dobbs novels about the English nurse, as I read this blog article. Thank you for sharing.

I was reminded of one of your Maisie Dobbs novels about the English nurse, as I read this blog article. Thank you for sharing.

reply

|

flag