Week Two in Paris

When I was twenty one, I spent a summer in Boulder, Colorado. I actually stayed outside the city, with an elderly couple in a small town called Gunbarrel. My commute into work was a half hour bus ride through some of the most incredible scenery. The first few mornings I was all eyes, staring out the bus window at the mountains in the distance. By the fourth morning I was either dozing or devouring a paperback. It wasn’t that I’d lost interest in the scenery. I’d just grown used to it. I took it for granted that there’d be a picture postcard shot at the end of every road we turned down. Back then, I was writing poetry. It wasn’t very good poetry. In my defence, I was twenty one. I was an English undergrad. I was living in Belfast. Everyone I knew was writing, (mostly terrible), poetry. I remember coming home from my American sojourn and writing what I thought was a terribly profound poem about how people can grow accustomed to anything, whether it be the Rocky Mountains or police helicopters hovering over your rooftop in South Belfast. I sincerely hope I never showed this poem to anyone. However, awful as it was, the sentiment’s true. It’s easy to stop noticing the every day. I’ve been thinking about that poem a lot this week.

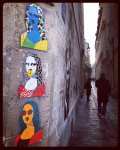

I’ve been in Paris for a fortnight now. I wouldn’t say I’m a regular Parisian yet, but I definitely feel like I’ve grown a little more used to the place. Two or three times I’ve actually caught myself thinking in French -albeit clunky GCSE French- and I’ve found myself way less self-conscious about making conversation. I can understand what’s being said to me and have a stab at speaking back and while I still feel a little clumpy and unsophisticated, (I’m thinking here of Conor Cleary’s incredible line about feeling like a blancmange in comparison to the elegant Spaniards in his poem about visiting Barcelona), I can sense myself placing an imagined distance between me and the tourists posing in their red berets in front of the Eiffel Tower. I know I don’t belong here but I feel less of an outsider than I did last week. I stride past the stunning church on the corner. I’ve stopped pausing outside every boulangerie window. I am becoming functional here.

I’ve established a routine. This seems to be helping with my productivity. I get up in the morning and write for four hours, walk to the boulangerie for a baguette, walk to some scenic spot or museum and force myself to be actively inspired for a few hours, write for another hour or so in a cafe, with a cafe creme to hand, then walk home for dinner, reading and a glass of wine. It is a very civilised way to put in the day and it seems to be working. I’ve been writing Postcard Stories each day based on the artwork I’ve seen. If you want to catch up on the first batch you can read them here. I’ve also written three short stories based on Agatha Christie’s novels and hidden them around the city. You can read the first two here and here. I’ve been to some readings and spent a wonderful afternoon listening to the American Poet Laureate Joy Harjo last Friday. She spoke particularly powerfully about art and activism and gave us lots to dissect over our post-reading glass of wine. I’ve also shocked myself by writing a substantial chunk of a Young Adult novel. I don’t want to jinx it, but I’m well over the 20,000 word hump and still powering on. I think Paris might be good for me.

I’ve also been thinking a lot about what it’s like to watch your news happen at a distance. This week it was particularly strange observing all the developments at Stormont, from another country where no one’s particularly interested in my wee corner of the world or its politics. This last year, traveling so much, I’ve watched most of the developments in British politics from hotel rooms and departure lounges in other countries. I’ve not yet been able to articulate how this feels. I think I need to write a longer essay about this at some stage. It’s a strange mix of isolation and also perspective. Being somewhere else allows you to observe your own home, and all the nuances of its political make up, in the context of a much bigger, even more complicated world. That’s good. It’s healthy. Paraphrasing Louis MacNiece here, but I keep coming back to that section in Autumn Journal where he talks about how self-obsessed we Northern Irish folk can be, how we imagine the world cares, when it really doesn’t. I like being forced to think about home in the context of America, or France, or India, or wherever I happen to be sleeping tonight. Yet it also feels a little lonely. When you’re far from home and great things happen there’s no one around to celebrate with. When it looks like everything’s falling apart, there’s no one who cares quite as much as the people who’ll actually have to live with the mess. I have to say I’ve been lucky this week. There’s a great bunch of artists resident in the Irish College who were more than happy to raise a glass to a more productive Stormont. Sometimes this is all it takes, to make you feel a bit more connected to home.

I watched Lost in Translation again last weekend. I haven’t seen it for over ten years. The soundtrack’s still as fresh as it was in 2003 and I also think Sofia Coppola completely nails the feeling of being far away from home. I have every sympathy for the character played by Bill Murray. He is nothing, if not, a blancmange throughout. There are so many shots and scenes in Lost in Translation which are metaphors for the complex relationship between distance and belonging. It’s like you’re observing your temporary home from a height, through several sheets of glass. It’s not having the right words to say and cobbling together something clumsy which has to suffice. It’s phoning home and not being able to translate this strange place, into a story people at home will understand. On Friday past I asked Joy Harjo how she manages to keep a tight connection to the specific places she writes about, when she’s spending so much of her life traveling elsewhere. She said she was still learning how to manage this. She’s been writing and traveling for fifty years. There’s little hope for me trying to figure this out, before I come back to Belfast in February.