Jan Carson's Blog

February 8, 2020

Blogging Off

[image error]

Hi folks, just to let you all know, I have a swanky new website over at www.jancarson.co.uk It’s a futile attempt to try and streamline my life. You can find events listing about up and coming workshops on the website, also information about my publications and means of contacting me for booking or rights enquiries. I’ve also decided to transfer my blog to the website and this means shutting down the old WordPress site. I’m going to do my best to transfer all the best archived blog articles over to the new website. Thank you for following along these last five years. I promise to continue posting nonsense about Agatha Christie, Casualty and old people over on the new website. Over and out. Jan

February 1, 2020

Come to Our Friendly Girls’ Evenings

[image error]

Oh won’t you come to our Friendly Girls’ Evenings. The regular crew are ever so nice.

There’s Molly with the auburn hair who lives out by the vicarage. Molly with the pretty frocks and the apple cheeks and those blue eyes red from constant sobbing and the slightest tremor in her wrists. You must have seen her by the bus stop. You can find her there most afternoons. She’s waiting for her fella. He hasn’t written in over a year. She often takes her knitting with her. She’s still working on that blue pullover. Now, don’t get us wrong. Molly isn’t lazy or incompetent. Molly’s actually a champion knitter. You should see the cardie she made for Bee’s youngest. Sure, it took first place at the village fete. She’s a wonder at the darning too. No, Molly’s just making that pullover last. She’ll knit a few rows then deftly unpick them, then start back in where her needles left off. She knows when she gets to the hem and knits the final navy blue stitch, they’ll be nobody to wear it. Molly knows her fella’s not coming back.

Never mind, Molly. Have you met Susan? Susan’s a darling. You’ve probably passed her in the street. She’s the one in the overalls and the filthy wellington boots. Susan’s not bothered about her appearance. She’s always got soil jammed under her nails. Susan’s never out of that allotment; up to her oxters in muck and weeds. What does she grow? Oh, all the usuals: marrows, potatoes, carrots, beets. And a drill or two of bits and bobs her fella left when he went to the Front. His boots. His books. His drawing pencils. Every stitch of clothes he had. His watch. His toothbrush. His front door key. There’s not a trace of him left in their wee house. Susan must know he’s not coming back. What does she think she’s doing, burying every last trace of her fella? Maybe she hopes some version of him will sprout from the seed of his best belongings. Maybe she’s trying to give him the funeral she knows he’s never going to have.

Forget Susan. It’s Marjorie you need to meet. Marjorie’s a sensible girl. She’s what we like to call, a brick. Marjorie takes good care of herself. She’s trim and fit; dear goodness you should see the waist on her. She’s no bigger at twenty three than she was when she joined our Girl Guide troop. Marjorie counts her calories and follows the Women’s League of Health and Beauty and goes early to bed most every night. Marjorie believes in a good night’s sleep. Marjorie also likes to nap through the day. In truth, Marjorie’s been in hibernation since September a year ago. She sleeps for twenty hours a day and only rises to eat and wash and do her keep fit manoeuvres in the living room with the curtains pulled. She says she’s keeping in shape for her fella. She says he likes a girlish figure. She says she wants to be ready for him. Sometimes if you catch Marjorie in those fragile moments when she’s just waking out of her one of her naps, she’ll tell you that she dreams of him. It’s easier, she’ll admit, when she’s fast asleep. Then she gets to be with her fella. Then she can pretend he’s coming back.

Oh won’t you come to our Friendly Girls’ Evening. We always have such a jolly time. We talk and giggle and tell such stories and only weep for the final hour. We won’t even hold your fella against you. It’s such a blessing that he came back. Oh yes Dear, we’ll be happy for you once you’re finally one of us. You must be a doll and refuse to listen to those ugly rumours. We can assure you, they’re simply not true. Those dreadful gossips in the WI are jealous -just terribly jealous- because they’re too old for the Friendly Girls. We were friendly to that last girl. We were kind. We welcomed her in. We certainly didn’t approach her husband. The very thought of it. To hear her talk you’d think we were desperate. You’d think that any old man would do. We’re not ready to forget our fellas. We still like to think they might come back. Besides, we have each other. We share our joys and share our heartache. We share everything in the Friendly Girls.

Inspired by Agatha Christie’s 1926 novel, “The Murder of Roger Ackroyd”

Dropped in the Irish Embassy, Berlin, Germany on Friday 31st January 2020

#MyYearWithAgathaC

January 31, 2020

Postcard Stories from Paris – Week Four

22nd January 2020

Paris, France

Helena Nolan

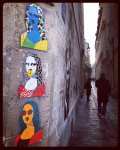

Meanwhile, outside the Louvre’s entrance, a small crowd has gathered at the base of the pyramid. They are American, Japanese, German, English; notably, not French. They are videoing, photographing and taking selfies, using selfie sticks recently purchased from the resident street vendors who also hawk keyrings of the Eiffel Tower, and kitchen aprons of the Mona Lisa, and four euro berets in primary colours, which will fall apart and shrink in the wash. They are carefully observing an installation which they consider -in their best High School French- to be tres interessant. A tiny robot -no bigger than a handbasin- is scuttling spider-like up the pyramid’s glass wall. The gathered crowds can’t help but stare. They whisper together. They speculate. They wait for an artist to emerge and explain her motivation; the story behind this robotty art. Half way up, the robot pauses, then pisses water across the glass. Two wipers appear in the place of antennae and scrape the windows ‘til they’re sparkling clean. The penny drops. The onlookers mutter. This isn’t art. It’s mere window cleaning. A few pocket their phones and wander off in pursuit of proper art. Most remain, transfixed and filming. This may not be the Mona Lisa, but neither do they have window cleaning robots in the various places where they come from.

23rd January 2020

Paris, France

Roisin O’Donnell

Even if I could not interpret the gallery notes for La Promenade du Dimanche au Tyrol, I would know instinctively that Jean Fautrier has not painted a Saturday afternoon dander, or a midweek jaunt around the park. No, the ten individuals captured in this painting were clearly made for the Sabbath. All ten, including the solitary male, are wearing ankle length skirts or longer. All are hatted. All stiff-necked. All look furiously glum. Their cheeks are blooming like rosy apples. The sweat sits thickly on their brows. You can tell they’ve marched briskly around the forest’s limits at what might be called, ‘a righteous clip.’ You can tell they’ve taken no time for chat. Most likely they do this walk every Sunday between morning service and evening prayers. Rain. Hail. Shine. These women keep walking, though they do not enjoy it one wee bit. You can tell this from their stoic expressions. They are not looking for our sympathy. These women know fine rightly, the Sabbath isn’t meant to be enjoyed.

24th January 2020

Paris, France

Aifric Mac Aodha

Five people are peering into the glass display case which houses Francesco Vezzoli’s sculpture Tortue de Soiree. Their faces are reflected in the polished gold surface of the tortoise. Their cell phone flashes bounce back at them, each one flaring like a shooting star. They have not paused to read the gallery notes. They do not know, as I now know, that this sculpture is based on Joris-Karl Huysman’s character Jean des Esseintes who, in the novel, A Rebours, buys a giant tortoise with which to decorate his house and displays this tortoise on an Oriental rug. Disappointed, when the tortoise’s dull shell does not create the desired aesthetic, he covers it in precious jewels. Though the poor creature looks terribly beguiling, the weight of so many diamonds and rubies eventually crushes it to death. And what is the moral of this story? It is a meditation on decadence and vanity, also something to do with artifice ie. the danger of becoming so very blinkered you overlook the natural moment; the beauty which requires no enhancement. I consider explaining this to the young woman standing next to me at the case. But she is otherwise occupied, wrestling with her selfie stick.

25th January 2020

Paris, France

Dragan Barbutovski

There is a secret chamber sunk beneath the Louvre’s floor. It runs the entire length of the museum yet is only known to a handful of curators and the most trusted of the security guards. In this room the decapitated heads of thousands of statues are stored and shelved like library books. Some lost their heads in revolutions, other were victims of time and erosion, or clumsy handlers in lesser museums who did not appreciate their ancient worth. In the dark, with the doors shut firmly, the heads do what heads do best. They talk and talk and rarely listen for mostly they were once the heads of important men and remain unduly enamoured with the sounds of their own voices. At first the heads talked at cross purposes, each one pontificating on a chosen theme. Then, a young curator with more wit than most thought to arrange them in conversational groups. Now, the religious heads can talk of religion and the angry heads can talk of war and, in the corner farthermost from the door, those heads formally belonging to the gods can kick up the most almighty racket, lamenting their much-reduced state and, buffered by a rack of placid saint heads, nobody else is bothered by them.

26th January 2020

Paris, France

Clara Ministral

Little Dancer Aged Fourteen, was his only sculpture to be exhibited during Degas’ lifetime. It was not without controversy and caused an unholy uproar at the Impressionist Exhibition of 1881. First, Degas toyed with the rules of sculpture by adding a tulle tutu and satin ribbon to his traditional bronze. Secondly, he challenged assumptions of form by portraying his tiny dancer stretching out her aching muscles, leg shot out like a dawdling lad. Surely he could have picked a more recognisable ballet pose, capturing his model on pointe or mid plie, like a graceful arching swan. Finally, Degas broke the rules of decency by giving his girl a snubbish nose, large ears and a kind of cool, defiant smirk. It is possible to see something animalistic in the way he has arranged her face. There were rumours about Degas’ relationship with his young model, Marie van Goethem. It was not uncommon in opera circle for dancers to sleep with their male protectors. Has Degas cast his little dancer as a prostitute? Perhaps, however, this is unfair. Later critics will come to read determination into her stubborn stance. This could well be the cut of a girl saying, ‘no!’ A young woman who definitely knows her own mind. No wonder Degas’ contemporaries were so unimpressed. They’d rarely encountered the likes of her.

27th January 2020

Paris, France

Roman Simic

Cuno Amiet’s giant painting Paysage de Neige, covers an entire wall of the Musee d’Orsay. This artwork is also know as Grand Hiver, or Big Winter to give it its English Translation. Nothing about this painting is small. Al least four fifths of the canvas is dominated by a white snow drift. Four feet or more of pure blankness ascends, uninterrupted, from the gallery floor to meet the thinnest strip of pale, grey sky. No trees. No houses. No jolly snowmen. No twinkling Christmas lights. Nothing to lift the bleak midwinter. Nothing to speak of a coming spring. This indeed is a big, big winter. It is thick and deep and all consuming. It seems to suggest the whole world is frozen. Yet, just off centre, to the lower left, a tiny smudge defies the white. Lean in. Look closer. Note arms and legs. A scarf. Two skis and grappling hooks. A blue, blue hat, the colour of summer. A pink face straining towards the edge of the frame. The ghost of something which might be a smile. He see something in the distance which we, the snow blind, cannot see.

28th January 2020

Paris, France

Andrew Cunning

The French designer, Charlotte Perriand spent weekends photographing objects she’d found on Normandy beaches. She called these ordinary items, treasures, though they were only lumps of wood and rocks, bits of shoes and broken bottles. She said they were smoothed and ennobled by the sea. As for objects, so with people. Remember the day you swam far out, somewhere off the County Down coast, then floated around in the briny water and let the current peel you clean? And afterwards felt easier and closer to everything, including yourself. How you thought of this as a kind of baptism which was good but nothing like the power and the glory of Perriand’s carefully chosen words. Now, you fully understand the process. You were smoothed and ennobled by the sea.

January 27, 2020

Mr Fish Does Not Fit into the Picture so Well

[image error]

It had long been Mr Fish’s dream to attend an English country house party of the sort which last for a single weekend. He’d read of them in the works of PG Wodehouse and other novels of a certain ilk and had developed a rather fixed notion of what such parties should involve. A hunt, of course. Ideally, a ball. A murder or two. Some localised haunting. Cigars and whisky in the library. A beautiful heiress with strained nerves. Gardens. Billiards. A po-faced butler. Smoked kippers for breakfast every morning. Obviously, the kipper situation wasn’t ideal. Mr Fish was not a barbarian. He would prefer not to eat his own. Perhaps, he reasoned, if presented with such a dilemma, he might excuse himself under the auspices of a dicky tummy. English people were always suffering from dicky tummies in the novels he liked to read.

Mr Fish was not English. In truth he knew not what he was. He’d spawned in a warm current off Greenland and been drifting ever since, keeping a careful distance from his numerous siblings, whom he found to be somewhat run of the mill. Did one hail from the place of one’s conception or the spot where one spent one’s formative years? Mr Fish was hopeful for the latter. He’d spent his youth and early childhood swimming around an oil rig, stationed West of Galway Bay. This rig was manned by a team of Liverpuddlians. Now, Mr Fish was always looking to better himself but he saw nothing worthy of emulation in the workers’ sloppy English or their manners, which were dreadfully base. Spitting. Swearing. Scratching their groins in a fashion Mr Fish found most uncouth. The foreman however, was a better breed. He wore a tie and well-pressed shirt, kept his work boots polished to a godly sheen and spoke with a clipped Kent accent. Mr Fish observed him every morning, taking his daily promenade around the rig with a paperback novel in hand. When these novels were duly finished and cast into the choppy sea, Mr Fish tracked them down and devoured them, savouring each delicious morsel of properly written English pomp.

It was here that he learnt of the country house, here he developed his great ambition and here he determined to make his way slowly East via ocean, sea, river and stream to England, which he considered his natural home. It took some months before he arrived at Chimneys’ Lake and a further month before he managed to make himself heard. He chose Miss Bundle as his primary contact for she was given to flights of fancy and spent long hours drifting around in a rowing boat. She seemed the most likely of the household contingent to appreciate a talking fish.

Mr Fish’s suspicions were spot on. Miss Bundle pronounced him a darling creature and scooped him up in an old punch bowl. Mr Fish would be the guest of honour at the following weekend’s house party. He was delighted to hear that a murder, two burglaries and a picnic supper were already on the cards. A spontaneous elopement was also rumoured, not to mention a betrayal or two. “Jolly good,” said Mr Fish, (this being something he’d learnt from his books). He envisioned himself in the midst of proceedings, perhaps swimming around the dining table in a purpose-built cut glass tank, offering charming observations about the décor and the ladies’ gowns. If the moment presented itself, he might even quote some choice morsels of English verse.

Miss Bundle was dreadfully apologetic but she felt it best to be above board. There’d be no possibility of Mr Fish dining with the regular guests. Neither would he be welcome in the library post dinner or on the terrace for G and Ts. The dear girl was truly, awfully sorry to have misled him. In truth, she’d seen Mr Fish as a kind of sideshow: an entertainment, much like the Bulgarian trumpet player or the Spanish Flamenco dancers who were due to perform on Saturday night.

“I thought Papa would be tickled to hear a talking fish,” she explained. “I’m awfully sorry for any upset.” When Mr Fish asked if things might’ve been different if he were a man, or even capable of walking on feet, Miss Bundle was quick to reassure him. It was nothing to do with his lack of feet. The bottom line was rather unpleasant. It wasn’t something she was proud of. Mr Fish was not now, nor ever had been, a genuinely English fish. Papa liked fish as much as the next man. It was foreigners he objected to. He didn’t mind them dancing for him, but dining together was out of the question, even if Mr Fish stayed inside his tank. Sadly, Mr Fish understood. He was disappointed, but not surprised. He’d read of such men in his English books.

Inspired by Agatha Christie’s 1925 novel, “The Secret of Chimneys”

Dropped on Sunday 26th January 2020 at le Jardins des Plantes, Paris, France

#MyYearWithAgathaC

5. The Secret of Chimneys

[image error]

“Mr Fish Does Not Fit into the Picture so Well”

It had long been Mr Fish’s dream to attend an English country house party of the sort which last for a single weekend. He’d read of them in the works of PG Wodehouse and other novels of a certain ilk and had developed a rather fixed notion of what such parties should involve. A hunt, of course. Ideally, a ball. A murder or two. Some localised haunting. Cigars and whisky in the library. A beautiful heiress with strained nerves. Gardens. Billiards. A po-faced butler. Smoked kippers for breakfast every morning. Obviously, the kipper situation wasn’t ideal. Mr Fish was not a barbarian. He would prefer not to eat his own. Perhaps, he reasoned, if presented with such a dilemma, he might excuse himself under the auspices of a dicky tummy. English people were always suffering from dicky tummies in the novels he liked to read.

Mr Fish was not English. In truth he knew not what he was. He’d spawned in a warm current off Greenland and been drifting ever since, keeping a careful distance from his numerous siblings, whom he found to be somewhat run of the mill. Did one hail from the place of one’s conception or the spot where one spent one’s formative years? Mr Fish was hopeful for the latter. He’d spent his youth and early childhood swimming around an oil rig, stationed West of Galway Bay. This rig was manned by a team of Liverpuddlians. Now, Mr Fish was always looking to better himself but he saw nothing worthy of emulation in the workers’ sloppy English or their manners, which were dreadfully base. Spitting. Swearing. Scratching their groins in a fashion Mr Fish found most uncouth. The foreman however, was a better breed. He wore a tie and well-pressed shirt, kept his work boots polished to a godly sheen and spoke with a clipped Kent accent. Mr Fish observed him every morning, taking his daily promenade around the rig with a paperback novel in hand. When these novels were duly finished and cast into the choppy sea, Mr Fish tracked them down and devoured them, savouring each delicious morsel of properly written English pomp.

It was here that he learnt of the country house, here he developed his great ambition and here he determined to make his way slowly East via ocean, sea, river and stream to England, which he considered his natural home. It took some months before he arrived at Chimneys’ Lake and a further month before he managed to make himself heard. He chose Miss Bundle as his primary contact for she was given to flights of fancy and spent long hours drifting around in a rowing boat. She seemed the most likely of the household contingent to appreciate a talking fish.

Mr Fish’s suspicions were spot on. Miss Bundle pronounced him a darling creature and scooped him up in an old punch bowl. Mr Fish would be the guest of honour at the following weekend’s house party. He was delighted to hear that a murder, two burglaries and a picnic supper were already on the cards. A spontaneous elopement was also rumoured, not to mention a betrayal or two. “Jolly good,” said Mr Fish, (this being something he’d learnt from his books). He envisioned himself in the midst of proceedings, perhaps swimming around the dining table in a purpose-built cut glass tank, offering charming observations about the décor and the ladies’ gowns. If the moment presented itself, he might even quote some choice morsels of English verse.

Miss Bundle was dreadfully apologetic but she felt it best to be above board. There’d be no possibility of Mr Fish dining with the regular guests. Neither would he be welcome in the library post dinner or on the terrace for G and Ts. The dear girl was truly, awfully sorry to have misled him. In truth, she’d seen Mr Fish as a kind of sideshow: an entertainment, much like the Bulgarian trumpet player or the Spanish Flamenco dancers who were due to perform on Saturday night.

“I thought Papa would be tickled to hear a talking fish,” she explained. “I’m awfully sorry for any upset.” When Mr Fish asked if things might’ve been different if he were a man, or even capable of walking on feet, Miss Bundle was quick to reassure him. It was nothing to do with his lack of feet. The bottom line was rather unpleasant. It wasn’t something she was proud of. Mr Fish was not now, nor ever had been, a genuinely English fish. Papa liked fish as much as the next man. It was foreigners he objected to. He didn’t mind them dancing for him, but dining together was out of the question, even if Mr Fish stayed inside his tank. Sadly, Mr Fish understood. He was disappointed, but not surprised. He’d read of such men in his English books.

Inspired by Agatha Christie’s 1925 novel, “The Secret of Chimneys”

Dropped on Sunday 26th January 2020 at le Jardins des Plantes, Paris, France

#MyYearWithAgathaC

January 25, 2020

Postcard Stories from Paris Week Three

15th January 2020

Paris, France

Anton Thompson-McCormick

Between 1996 and 2011, the German photographer Ursula Schulz-Dornburg, travelled throughout Armenia, photographing isolated bus stops. These elaborate structures are leftovers from the golden age of Socialist building. They bear little resemblance to the traditional notion of a bus stop. Each is its own small flight of fancy. A sculpture. A triumph. A grand indulgence. Form trumping function at ever turn. And, if it is odd to come across a miniature gas station plunked down in the middle of the desert, or Graeco-Roman pillars, rising from the roadside dirt, then it is odder still to see the actual commuters standing next to them. Clutching briefcases and children. Dressed for work or a cocktail party. Summered. Wintered. Ancient. Timeless. It’s impossible to tell how long these people have been waiting: an hour, a week, a century or more. Or where they think they’re headed, standing beneath those fantastic shades. Vegas. St Tropez. Beijing. London. Anywhere that isn’t here. Their faces remain calm and patient, staring stoically down the lens, whilst all around them the paint is peeling, the metal rusting, the fancy gilt-work losing its lustre. This is tiny, land-locked Armenia. The year is 1996. These people are very good at waiting. They have been practicing for many years. Perhaps if they stand here long enough, the future will eventually come for them.

16th January 2020

Paris, France

Patrick McGuinness

Ursula Schulz-Dornburg – Uprising Square 2000

Here are some photos of Russian men: three of them, or sometimes four. They are close-shaved, short-sleeved, suggesting summer. They are riding an escalator in the centre of St Petersburg. Though we can assume these men are moving -it is an escalator after all- there is no movement in an image. This is merely a freeze-framed second. A still snapshot. A static slice of men in transit. They’re trapped within the confines of the frame like cretaceous flies in amber, frozen between take off and arrival, paused forever in mid-flight mode. Who can tell their direction of travel? What looks like up might well be down. As with escalators, so with Russia. As with Russia, the rest of us.

17th January 2020

Paris, France

Ronan Hession

On the ground floor of the Musee d’Art Moderne de Paris, Philippe Parreno’s installation of twenty giant birthday candles, decorated in golden helter skelter stripes, is gathering dust in a quiet corner, propped against an empty wall. Meanwhile, elsewhere on the mezzanine floor, Raymond Hain’s painting Saffa, depicts a books of two dozen unstruck matches, each match rendered in relief and approximately two feet tall. I wish to broker a casual acquaintance between the candles and the matches. I imagine they’d get on like a house on fire. I am also naïve enough to believe that somewhere on the second or third floor -up where my bog standard pass won’t take me- there is a twelve foot birthday cake cast in plastic or wool or bronze just waiting for some progressive curator to get the party started and exhibit him next to Parreno and Hains where he quite clearly belongs.

18th January 2020

Paris, France

Piia Leino

In the 1920’s Parisian-born sculptor, Gaston Lachaise was taken with the idea of weightlessness. His research led him to the circus where he studied acrobats and trapeze artists, noting the way their bodies appeared to float on air as other lessers might float on water. How they moved so gracefully, blurring the space between here and there so they seemed to exist outside of time. This might seem at odds with his 1927 sculpture. Though he entitled it Floating Woman, this lady is dreadfully, solidly grounded. For there’s nothing flighty about bronze and there is an awful lot of it here. In the woman’s arms, like two ham joints, extended above her colossal breasts, and her legs, which swim like sleek fat seals, all the way down to meet her feet, which are delicately crossed at the ankle and very much on point. This lady is large and stubborn with it. She extends herself to fill the space. It is only closer inspection which reveals the point -a hand’s width, no more- where every ounce of her big bronze body rests on a single section of dimpled thigh. The effect is rather elegant. She carries her weight like a flying trapeze. Or a Jesus Bug skating across the water’s surface; barely touching the skin of it.

19th January 2020

Paris, France

Rick O’Shea

In this unnamed installation by Roger Ballen, an elderly woman is knitting herself. Her arms and hands are mechanised so her needles click clack, her yarn keeps coming in thick strands of palest gray, and the knitted length of her knitted body creeps closer and closer to her pale, pinched face. It is Sunday now and she’s up to her neck in a long, knitted bandage. She does not look best pleased. Still, she keeps on knitting and knitting, drowning herself in blanket stitch. If she stops now, she’d pass for a toilet roll lady; knit body concealing a roll of Andrex. But, if she continues to wield those needles, the knitting will soon be over her head. By Wednesday morning she’ll be a goner, suffocated by her own pale gray, double knit, lambswool shroud. She’ll have no one to blame for this but herself.

20th January 2020

Paris, France

Bettina Munch

French artist, Robert Filliou travelled round Paris with a gallery in his hat. La Galerie Legitimie, began life as a simple beret and later morphed into a bowler hat which could be worn upon the person and contained various drawings, prints and paintings. Later, wishing to add small objects and framed paintings to his exhibition, Filliou progressed on to a top hat. Formed from durable Perspex, this final incarnation of La Galerie Legitimie, had the advantage of being see-through, so passersby could view the artwork without forcing Filliou to remove his hat. The disadvantages however were myriad. The rain made an awful clatter on the brim. The sharp edges cut into his forehead, condensation collected within the funnel and it was always catching on low doorframes. Last, but by no means least, Filliou’s poor ears, used to the comfort of a woollen beret, were now frozen in the Parisian cold.

21st January 2020

Paris, France

David McNair

During the twenty eight month siege of Leningrad, a number of the botanists who worked at the Vavilov Institute of Plant Industry chose to starve to death rather than consume the Institute’s collection of seeds and plant samples. The Soviet officials who’d taken the time to strip the city of its artistic treasures forgot, or possibly overlooked, the world’s largest seed collection. Perhaps they did not realise it was also a treasure. Maybe they did not understand that even the smallest and most insignificant seed could still be a symbol of hope. The scientists must have struggled to protect these samples from Leningrad’s desperate residents, not to mention the city’s hungry rats. But these formidable men and women chose to sacrifice everything for the idea of future plants. And here they are now -or at least a section- of the two hundred and fifty thousand samples which they managed to save. The German photographer Ursula Schulz-Dornburg has captured three dozen distinct ears of corn. First, on camera; framed and mounted. Then, in individual metal cases. Each one long, rectangular and lidded. These tiny coffins form a funeral procession around the edge of the gallery. This seems nothing, if not appropriate, given their dreadful history.

January 22, 2020

Ghosts Don’t Affect Typewriters

[image error]

This was not Anne’s first stint as a secretary. After school she’d trained as a typist and worked in a junior capacity at the local library, firing out letters about overdrawn books and unpaid fines. It was simple work and not at all taxing. She often found that she’d completed most of her tasks by mid-afternoon and had to linger over her last few letters poking at the typewriters keys with one finger when she usually flew across the board. When the job came up at the Foreign Office, Anne applied immediately. It wasn’t an enormous improvement salary-wise, but she hoped there might be more opportunity for promotion and -though this was neither stated openly, nor even implied in the listing- she wondered if she might get to work on classified documents. Whilst working at the library Anne had read her way through all their thrillers and made a significant dent in crime fiction. Consequently, she imagined London to be full of murderers and spies.

The Foreign Office was something of a disappointment. It did not look like it looked in books. Anne had been expecting something regal and rather imposing but the typing pool was based in the dingy basement of an ordinary office block. To the right was a Lyons’ tea shop. To the left a solicitors. Anne’s desk was situated in the corner, beneath one of those thin basement windows through which she could see pedestrians passing on the pavement outside, though only from the shins down. Her desk mate was a girl from Sheffield, by the name of Doreen who, when she really got going with her typing, made an infuriating humming noise. Anne thought of asking if she might reel it in but, wishing to make a good impression, instead leant across the desk and asked where was decent for lunch ‘round here, and would Doreen care for some company.

Over lunch, Doreen told Anne about the ghosts. “I say,” she said, as she picked the tomatoes out of her quiche, “you aren’t the sort who’s bothered by ghosts?” Anne wasn’t. The library had been fairly well-haunted and she’d once spent a summer on a barge, tormented by the spirit of a boy who’d drowned in the canal while trying to fish his football out. Anne didn’t mind the odd ghost, she explained to Doreen, so long as they didn’t interrupt her work. She’d be grand in the office, Doreen reassured her. Their ghosts were quiet secretarial types. They lingered demurely by the coffee table flicking through hairdressing magazines and sometimes primped in the bathroom mirrors. They certainly didn’t affect the typewriters. They were very conscientious ghosts.

“Good to hear,” said Anne and tried to hide her disappointment. She’d hoped the Foreign Office might’ve had a better class of ghost. If there weren’t to be spies in her immediate future, an interfering ghost -the sort intent on bringing down the system- would have been a jolly good alternative. It seemed such a shame to be working for the Foreign Office and not see any significant action, so Anne resolved to create her own. She peppered her typing with secret messages. Send in the troops. Alert all agents. Abort mission. Code red. Code red. She brought paperback novels into the office and kept them hidden in her desk. When requiring inspiration, she’d flick from page to page until she discovered a phrase or sentence which sounded sufficiently authoritative. By the third week of her employment she’d instigated an assassination, declared war upon the Isle of Man and blown the cover of sixteen different secret agents stationed across the USSR.

It didn’t take much investigation to trace these missals back to Anne’s desk. She was thrilled to be summonsed to the big boss’s office; more thrilled to be accused of espionage. She’d been planning her defence for the last two weeks. She was sure her alibi was watertight. Anne smiled confidently at the big boss and his secretary, who was taking notes, at all the gathered operatives “It wasn’t me,” she said, shrugging slightly, “it seems the ghosts have learnt how to affect typewriters. This one must be working for the other side.”

Inspired by Agatha Christie’s 1924 novel, “The Man in the Brown Suit”

Dropped on 21st January 2020 in the Centre Culturel Irlandais, Paris France

#MyYearWithAgathaC

January 19, 2020

Postcard Stories from Paris – Week Two

8th January 2020

Paris, France

Sinead MacAodha

In this picture, which is called Two Hunting Dogs Tied to a Tree Stump, a brown and white dog and a dark brown dog are tied to a tree stump. The first dog is sitting down, staring sideways towards the painting’s gilt frame. The second dog stands, head bowed, staring directly at the painter, who most likely is his owner, or so the gallery notes lead me to believe. The gallery notes are also quick to point out this 1548 oil painting by Jacopo dal Ponte is the first commissioned animal portrait in Western painting and therefore responsible for setting a trend. Countless posed kittens, ponies and puppies in baskets can trace their origins back to these two dogs. Not least the two bland watercolours of my mother’s favourite cats, commissioned posthumously and currently gracing her living room wall. I’d like to thank dal Ponte personally for that. And also offer commiserations for the fact Two Hunting Dogs is displayed in the Louvre’s Salle des Etats, directly behind the Mona Lisa’s left shoulder. Though this small painting is passed by some ten millions visitors each year, it generally goes all but unnoticed by all but the die hard dog lovers. Poor old Jacopo dal Ponte. Poor old tied up hunting dogs.

9th January 2020

Paris, France

Alan and Cheryl Meban

The Galerie d’Apollon of the Louvre houses what’s left of the French crown jewels. They are, I’m disappointed to admit, much like every other set of crown jewels. Which is to say, sparkly, ostentatious and terribly impractical. What’s more intriguing by miles is the display of empty, red leather cases made by Jean-Baptist-Nicolas Gouverneur, each one specifically designed to hold a single crown or diamond necklace or miniature, military sword. I’m particularly drawn to these cases because each is the perfect outline of the object it’s intended to hold. Like the platonic ideal of sword or crown, but approximately two to three centimetres bigger, each bulge and flourish, each fat diamond and decorative cross, has been carefully moulded out of leather to form a plush-lined second skin. This puts me in mind of the old cartoons I used to love. Mickey Mouse. Daffy Duck. All the various Looney Tunes whose birthday presents were never square or any sort of uniform shape but rather perfect replicas of trains and tennis racquets, gift-wrapped and ribboned so there was never any real surprise to be had in the unwrapping. And this makes me wonder about the French Royals. Were they a mischievous bunch? Did they ever, just for a laugh, stick a sceptre in the sword box or swap the King’s crown for a fancy necklace?

10th January 2020

Paris, France

Marius Burokas

In praise of perfect palindromes. For example, the French actor Leon Noel, who died in 1913, just before the War. His body is buried next to the bodies of his mother and father who didn’t even bother to rhyme. They preside over the farthermost corner of the 20th division of Pere-Lachaise. A Gustave Deloye bust of Leon Noel’s perfect head sits atop a perfectly hewn plinth. Note the collar raised equally on each shoulder, the eyes set equidistant from the nose, the hair receding in perfect, carbon copy curls round both of his perfectly balanced ears. Imagine some twelve feet beneath his perfectly pitched chin, a perfectly inverted plinth and bust of Leon Noel’s identical twin brother, Noel Leon who died at midnight on the same day, perfectly mirroring Leon Noel’s noon, and has been buried upside down at a one hundred and eighty degree angle for continuity’s sake.

11th January 2020

Paris, France

Anne Griffin

At first glance it would appear that the Marquise d’Orvilliers is simply having a bad hair day. While her neighbours mounted to left and right are perfectly plaited, ringleted and coiffed according to the current trend, her own mad bap of graying curls is barely contained by a single red ribbon, run Rambo-style across her head. Demurely dressed in funeral blacks, though this is actually an engagement portrait, she sits side saddle on a chair looking podgy and distinctly non-plussed. No jewels. No make-up. No opulent drapes. No lap dog or fawning children. One might assume the eighteen year old Marquise to be an old maid before her time. Until, closer scrutiny of the gallery notes reveals the artist’s specific intention: to paint the woman as a good Protestant. Austere is the aesthetic he was aiming for: cold light, blank wall, a bland minimum of accessories. Pity the sitter for he’s truly nailed it. Only a mother could love that face, or the young officer of the Royal Court who, knowing her father to be filthy rich, has recently asked for her dumpy hand.

12th January 2020

Paris, France

Yan Ge

In Le Cabinet Tessin, Swedish artist Peter Johanssen has constructed an elaborate wooden labyrinth though the permanent collection of the Institute Tessin. Small mug-sized portholes appear at interval allowing visitors access to tiny circles of the paintings and sculptures. Through the thirtieth of these round windows, a fragment of the Swedish painter, Einar Jolin’s wife, Tatiana can be viewed. She appears to be wearing a leopard-skin coat and sits with both hands resting on her lap. Her left hand sports a gold wedding band. Her right, a ruby-studded ring and a charm bracelet of gold and bronze medallions. If the frame were not focused on this tight section you might well have lingered on the model’s pretty face and missed the tiny cross emerging from her jacket sleeve, her fingernails filed to glamorous points, her hands crossed decisively on her lap, like the hands of a more adamant woman. It is hard to believe that these strong hands belong to that pale and passive face. In the case of Tatiana Angelini-Scheremetiew, seeing less means seeing more.

13th January 2020

Paris, France

Radmila Radovanovic

It is almost five hundred years since the lady first met the unicorn. For five hundred years now, they have been gazing into each others’ eyes. Each remembers their introduction clearly. The unicorn smiled first. The lady smiled back. Overcome by the pathos of this moment, the unicorn rose up on his hind legs and raised a flag to mark the occasion and danced a happy unicorn dance. The lady looked at the unicorn and she too knew this moment was particularly charged and required something like revelry. So she demanded six new dresses, four fruit trees and a serving girl, bearing vessels of sumptuous treats, a lavish tent and a court of beasts to attend her whimsy which included lions, monkeys, and a Pekinese. Five hundred years on, the moment’s worn a little thin; frayed, you might say, around the edges. The lady’s still smiling, so’s the unicorn, but if you look closely, you’ll notice their faces are strained and they’re no longer dancing, or even talking, just posed like strangers at a party, locked in the dullest of conversations, each one wishing that someone, anyone, even that monkey, would cut in and end this infernal charade.

14th January 2020

Paris, France

Alexandra Buchler

The young embroiderers of 13th Century France are not to be trusted with more complex pieces. Though an apprenticeship can last up to eight years, a girl in her sixth or seventh year might still be stuck with background work. Forests. Mountains. Sea and walls. So many walls. So much grey thread. For most of these scenes are religious; set in churchy spots. Picture the bold and brassy lass – Marie perhaps or Genevieve- who, seven years into a long, long learning, chances her arm and her needlepoint, to embroider a tiny effigy of saint somebody-or-other, (one of the more minor examples), in the corner of a tapestry. Only to be reprimanded. Only to be put in her place. Only to have her careful stitchwork unpicked by an older woman who knows the saints and apostles, the blessed virgin and himself, (infant, adult and crucified), are all embroidered by ancient experts, and stitched on at a later date. Where’s the fun in that? thinks the girl. Hers is the daring of the young; the desire to leave a permanent mark.

January 16, 2020

La Petite Acrobate With Her Wrists of Steel

[image error]

The acrobat was born with wrists of steel. Her mother had not envisioned this though later, with hindsight she will recall the afternoon her lover -the acrobat’s father- lay beside her on the living room couch, affixing fridge magnets to the dome of her belly. She’d sensed a certain umbilical tug as he peeled and positioned them to form a belt. She had assumed this feeling normal. This was her first baby after all. Perhaps all infants were magnetic. Perhaps she had a sticky womb.

Giving birth was a painful process. The hands came first and then the wrists. This felt so much like expelling a cheese grater, the poor woman passed out from the pain. She woke ten minutes later to find herself the reluctant mother of a pink-faced girl with metal wrists. Delirious from the trauma, and the gas and air she’d been sucking on, she looked down at the baby’s fists and demanded that, “someone, anyone, a locksmith ideally, take the bloody handcuffs off my girl.” When she finally realised these were her daughter’s actual wrists, no more removable than a foot or head, she howled for twenty four hours straight. Then bundled the baby up in a blanket and placed this parcel in an orange crate and asked her husband, (who was not, nor ever had been, the baby’s father), to leave the crate outside the circus with a note reading, “this one belongs with you.”

The husband was not as bold as the lover. He always did as he was told. He gave the baby to the circus and never spoke of her again. The woman went on to have four more children. A girl with telephones for ears. A boy with a retractable snorkel in place of a nose. And twins, (one of either sort), whose middle sections were completely see-through, as if they’d been blown from a sheet of glass. Her husband, having acquired a rake of orange crates, donated his children respectively, to the telephone exchange, the Royal Navy and the aquarium which had recently opened next to the pier. The couple never attempted children again. Just to be on the safe side, they made a point of sleeping in separate beds.

Meanwhile the girl with wrists of steel was growing up in her circus home. She was small for her age but very determined. The steel made her strong and this strength was good. It helped her say no, when they suggested she belonged with the sideshow freaks. It gave her the grit to persevere when her trapeze career simply wouldn’t take off. Her wrists of steel were far too heavy to float and fly through the air like the beautiful bird she needed to be. And when her juggling went sideways -fiery clubs flying off into the crowd- she understood her wrists were a bit unwieldy but could not bring herself to curse them. Surely there should be some place in the circus for a girl with wrists of steel.

And there was. There is. She’s now blissfully happy in her new position as petite acrobate, apprentice to the Great Grandini, whose specialities are contortion and elaborately-sequined leotards. She turns cartwheels round the ring for hours, never succumbing to the slightest twinge. She holds the Guinness world record for the longest handstand and the longest handstand on one hand and might, next year, wrists-permitting, make an attempt on a third world record, the longest handstand underwater. She’s currently undergoing rust proofing but hopes to be match fit by March. She also likes to hang off things. Ladders. Beams. Window ledges. One handed. Two handed. By her fingertips. She loves the feeling of total abandon which comes with standing on thin air. Some would call her steel wrists are shackles. The girl would disagree. She knows they’re the very thing which makes her free.

Based on Agatha Christie’s novel, Murder on the Links

Dropped at Square de L’Ile de France, Paris, France on 15th January 2020

#MyYearWithAgathaC

January 15, 2020

Week Two in Paris

When I was twenty one, I spent a summer in Boulder, Colorado. I actually stayed outside the city, with an elderly couple in a small town called Gunbarrel. My commute into work was a half hour bus ride through some of the most incredible scenery. The first few mornings I was all eyes, staring out the bus window at the mountains in the distance. By the fourth morning I was either dozing or devouring a paperback. It wasn’t that I’d lost interest in the scenery. I’d just grown used to it. I took it for granted that there’d be a picture postcard shot at the end of every road we turned down. Back then, I was writing poetry. It wasn’t very good poetry. In my defence, I was twenty one. I was an English undergrad. I was living in Belfast. Everyone I knew was writing, (mostly terrible), poetry. I remember coming home from my American sojourn and writing what I thought was a terribly profound poem about how people can grow accustomed to anything, whether it be the Rocky Mountains or police helicopters hovering over your rooftop in South Belfast. I sincerely hope I never showed this poem to anyone. However, awful as it was, the sentiment’s true. It’s easy to stop noticing the every day. I’ve been thinking about that poem a lot this week.

I’ve been in Paris for a fortnight now. I wouldn’t say I’m a regular Parisian yet, but I definitely feel like I’ve grown a little more used to the place. Two or three times I’ve actually caught myself thinking in French -albeit clunky GCSE French- and I’ve found myself way less self-conscious about making conversation. I can understand what’s being said to me and have a stab at speaking back and while I still feel a little clumpy and unsophisticated, (I’m thinking here of Conor Cleary’s incredible line about feeling like a blancmange in comparison to the elegant Spaniards in his poem about visiting Barcelona), I can sense myself placing an imagined distance between me and the tourists posing in their red berets in front of the Eiffel Tower. I know I don’t belong here but I feel less of an outsider than I did last week. I stride past the stunning church on the corner. I’ve stopped pausing outside every boulangerie window. I am becoming functional here.

I’ve established a routine. This seems to be helping with my productivity. I get up in the morning and write for four hours, walk to the boulangerie for a baguette, walk to some scenic spot or museum and force myself to be actively inspired for a few hours, write for another hour or so in a cafe, with a cafe creme to hand, then walk home for dinner, reading and a glass of wine. It is a very civilised way to put in the day and it seems to be working. I’ve been writing Postcard Stories each day based on the artwork I’ve seen. If you want to catch up on the first batch you can read them here. I’ve also written three short stories based on Agatha Christie’s novels and hidden them around the city. You can read the first two here and here. I’ve been to some readings and spent a wonderful afternoon listening to the American Poet Laureate Joy Harjo last Friday. She spoke particularly powerfully about art and activism and gave us lots to dissect over our post-reading glass of wine. I’ve also shocked myself by writing a substantial chunk of a Young Adult novel. I don’t want to jinx it, but I’m well over the 20,000 word hump and still powering on. I think Paris might be good for me.

I’ve also been thinking a lot about what it’s like to watch your news happen at a distance. This week it was particularly strange observing all the developments at Stormont, from another country where no one’s particularly interested in my wee corner of the world or its politics. This last year, traveling so much, I’ve watched most of the developments in British politics from hotel rooms and departure lounges in other countries. I’ve not yet been able to articulate how this feels. I think I need to write a longer essay about this at some stage. It’s a strange mix of isolation and also perspective. Being somewhere else allows you to observe your own home, and all the nuances of its political make up, in the context of a much bigger, even more complicated world. That’s good. It’s healthy. Paraphrasing Louis MacNiece here, but I keep coming back to that section in Autumn Journal where he talks about how self-obsessed we Northern Irish folk can be, how we imagine the world cares, when it really doesn’t. I like being forced to think about home in the context of America, or France, or India, or wherever I happen to be sleeping tonight. Yet it also feels a little lonely. When you’re far from home and great things happen there’s no one around to celebrate with. When it looks like everything’s falling apart, there’s no one who cares quite as much as the people who’ll actually have to live with the mess. I have to say I’ve been lucky this week. There’s a great bunch of artists resident in the Irish College who were more than happy to raise a glass to a more productive Stormont. Sometimes this is all it takes, to make you feel a bit more connected to home.

I watched Lost in Translation again last weekend. I haven’t seen it for over ten years. The soundtrack’s still as fresh as it was in 2003 and I also think Sofia Coppola completely nails the feeling of being far away from home. I have every sympathy for the character played by Bill Murray. He is nothing, if not, a blancmange throughout. There are so many shots and scenes in Lost in Translation which are metaphors for the complex relationship between distance and belonging. It’s like you’re observing your temporary home from a height, through several sheets of glass. It’s not having the right words to say and cobbling together something clumsy which has to suffice. It’s phoning home and not being able to translate this strange place, into a story people at home will understand. On Friday past I asked Joy Harjo how she manages to keep a tight connection to the specific places she writes about, when she’s spending so much of her life traveling elsewhere. She said she was still learning how to manage this. She’s been writing and traveling for fifty years. There’s little hope for me trying to figure this out, before I come back to Belfast in February.