Postcard Stories from Paris Week Three

15th January 2020

Paris, France

Anton Thompson-McCormick

Between 1996 and 2011, the German photographer Ursula Schulz-Dornburg, travelled throughout Armenia, photographing isolated bus stops. These elaborate structures are leftovers from the golden age of Socialist building. They bear little resemblance to the traditional notion of a bus stop. Each is its own small flight of fancy. A sculpture. A triumph. A grand indulgence. Form trumping function at ever turn. And, if it is odd to come across a miniature gas station plunked down in the middle of the desert, or Graeco-Roman pillars, rising from the roadside dirt, then it is odder still to see the actual commuters standing next to them. Clutching briefcases and children. Dressed for work or a cocktail party. Summered. Wintered. Ancient. Timeless. It’s impossible to tell how long these people have been waiting: an hour, a week, a century or more. Or where they think they’re headed, standing beneath those fantastic shades. Vegas. St Tropez. Beijing. London. Anywhere that isn’t here. Their faces remain calm and patient, staring stoically down the lens, whilst all around them the paint is peeling, the metal rusting, the fancy gilt-work losing its lustre. This is tiny, land-locked Armenia. The year is 1996. These people are very good at waiting. They have been practicing for many years. Perhaps if they stand here long enough, the future will eventually come for them.

16th January 2020

Paris, France

Patrick McGuinness

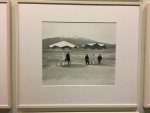

Ursula Schulz-Dornburg – Uprising Square 2000

Here are some photos of Russian men: three of them, or sometimes four. They are close-shaved, short-sleeved, suggesting summer. They are riding an escalator in the centre of St Petersburg. Though we can assume these men are moving -it is an escalator after all- there is no movement in an image. This is merely a freeze-framed second. A still snapshot. A static slice of men in transit. They’re trapped within the confines of the frame like cretaceous flies in amber, frozen between take off and arrival, paused forever in mid-flight mode. Who can tell their direction of travel? What looks like up might well be down. As with escalators, so with Russia. As with Russia, the rest of us.

17th January 2020

Paris, France

Ronan Hession

On the ground floor of the Musee d’Art Moderne de Paris, Philippe Parreno’s installation of twenty giant birthday candles, decorated in golden helter skelter stripes, is gathering dust in a quiet corner, propped against an empty wall. Meanwhile, elsewhere on the mezzanine floor, Raymond Hain’s painting Saffa, depicts a books of two dozen unstruck matches, each match rendered in relief and approximately two feet tall. I wish to broker a casual acquaintance between the candles and the matches. I imagine they’d get on like a house on fire. I am also naïve enough to believe that somewhere on the second or third floor -up where my bog standard pass won’t take me- there is a twelve foot birthday cake cast in plastic or wool or bronze just waiting for some progressive curator to get the party started and exhibit him next to Parreno and Hains where he quite clearly belongs.

18th January 2020

Paris, France

Piia Leino

In the 1920’s Parisian-born sculptor, Gaston Lachaise was taken with the idea of weightlessness. His research led him to the circus where he studied acrobats and trapeze artists, noting the way their bodies appeared to float on air as other lessers might float on water. How they moved so gracefully, blurring the space between here and there so they seemed to exist outside of time. This might seem at odds with his 1927 sculpture. Though he entitled it Floating Woman, this lady is dreadfully, solidly grounded. For there’s nothing flighty about bronze and there is an awful lot of it here. In the woman’s arms, like two ham joints, extended above her colossal breasts, and her legs, which swim like sleek fat seals, all the way down to meet her feet, which are delicately crossed at the ankle and very much on point. This lady is large and stubborn with it. She extends herself to fill the space. It is only closer inspection which reveals the point -a hand’s width, no more- where every ounce of her big bronze body rests on a single section of dimpled thigh. The effect is rather elegant. She carries her weight like a flying trapeze. Or a Jesus Bug skating across the water’s surface; barely touching the skin of it.

19th January 2020

Paris, France

Rick O’Shea

In this unnamed installation by Roger Ballen, an elderly woman is knitting herself. Her arms and hands are mechanised so her needles click clack, her yarn keeps coming in thick strands of palest gray, and the knitted length of her knitted body creeps closer and closer to her pale, pinched face. It is Sunday now and she’s up to her neck in a long, knitted bandage. She does not look best pleased. Still, she keeps on knitting and knitting, drowning herself in blanket stitch. If she stops now, she’d pass for a toilet roll lady; knit body concealing a roll of Andrex. But, if she continues to wield those needles, the knitting will soon be over her head. By Wednesday morning she’ll be a goner, suffocated by her own pale gray, double knit, lambswool shroud. She’ll have no one to blame for this but herself.

20th January 2020

Paris, France

Bettina Munch

French artist, Robert Filliou travelled round Paris with a gallery in his hat. La Galerie Legitimie, began life as a simple beret and later morphed into a bowler hat which could be worn upon the person and contained various drawings, prints and paintings. Later, wishing to add small objects and framed paintings to his exhibition, Filliou progressed on to a top hat. Formed from durable Perspex, this final incarnation of La Galerie Legitimie, had the advantage of being see-through, so passersby could view the artwork without forcing Filliou to remove his hat. The disadvantages however were myriad. The rain made an awful clatter on the brim. The sharp edges cut into his forehead, condensation collected within the funnel and it was always catching on low doorframes. Last, but by no means least, Filliou’s poor ears, used to the comfort of a woollen beret, were now frozen in the Parisian cold.

21st January 2020

Paris, France

David McNair

During the twenty eight month siege of Leningrad, a number of the botanists who worked at the Vavilov Institute of Plant Industry chose to starve to death rather than consume the Institute’s collection of seeds and plant samples. The Soviet officials who’d taken the time to strip the city of its artistic treasures forgot, or possibly overlooked, the world’s largest seed collection. Perhaps they did not realise it was also a treasure. Maybe they did not understand that even the smallest and most insignificant seed could still be a symbol of hope. The scientists must have struggled to protect these samples from Leningrad’s desperate residents, not to mention the city’s hungry rats. But these formidable men and women chose to sacrifice everything for the idea of future plants. And here they are now -or at least a section- of the two hundred and fifty thousand samples which they managed to save. The German photographer Ursula Schulz-Dornburg has captured three dozen distinct ears of corn. First, on camera; framed and mounted. Then, in individual metal cases. Each one long, rectangular and lidded. These tiny coffins form a funeral procession around the edge of the gallery. This seems nothing, if not appropriate, given their dreadful history.