The Ocean and the Waves

When I was a child, we used to go to Ocean City, Maryland every summer. We used to drive in our old car, my brother and me in the back seat playing some game — usually “Infinite Questions,” which I had made up and which involved one person thinking of an object while the other asked as many questions as he or she wanted, in order to figure out what that object could be. Sometimes we sang “100 Bottles of Beer on the Wall.” There was no air conditioning, so we rolled the windows down, manually of course.

When we got to Ocean City, we always stayed at a small hotel — I would admire the big hotels where the wealthier people stayed, with their private beaches. But our small hotel was close to the public beach, so we would spend the day playing in the sand or swimming in the ocean, then go in the evening to have dinner at the crab shack, where they gave you a bunch of cooked crabs, a mallet, and some pieces of bread to go with the crab meat. The tables looked like picnic tables and were covered with brown paper, because you were doing to make a mess. Later, we might walk along the boardwalk. At the end of the boardwalk was a sort of fair, and one summer I remember there was a man who would guess various things about you, including your profession, and if he could not guess in three tries you would get a prize. My mother challenged him to guess her profession. He asked to look at her hands, then guessed that this short woman with two children and a Central European accent was a doctor on the second try.

It was a cheap summer vacation, and we went almost every summer — I think because my mother remembered her summers as a child at Lake Balaton, and she had a sense that getting children to water was simply what one did in the summer. We spent a lot of time in the ocean — that’s where I learned to swim among the waves.

All of this happened, but at the same time it’s part of a metaphor, because what I want to write about is the difference between the ocean and the waves.

When you swim in the ocean, you’re constantly bobbing up and down from the motion of the waves. But if you dive underneath, what you encounter is a sense of stillness — under the surface, the water does not appear to be moving. (Of course, there are such things as undertows, which are very dangerous. But most of the time, the water under the waves feels still.) Sometimes the waves are small, and they lap at you like a cat’s tongue. Sometimes they’re larger, and then they can be scary, especially when you’re a not-very-large girl treading water. It took me several summers to learn how to deal with those larger waves. What you do is, you dive under them. You dive into the stillness, and the wave passes over you. Then, you emerge on the other side.

Here comes the metaphor. We are all in the ocean, and there are so many waves! It may be an illusion that life seemed to be calmer when I was a child, back when telephones were securely anchored to the kitchen wall and could not follow you about everywhere you went. You could watch the news for an hour in the evening — you did not carry it around in your pocket. I don’t know, it certainly seems to me that we are swimming in a more turbulent ocean, and yet that turbulence may also be an illusion. All times are turbulent, after all. It’s just that we get so much information, more than we can really process. The waves come at us so quickly.

When I started teaching research techniques to my students, the difficult part was finding information. Now, the difficult part is sorting through all the information we have. That’s what we have to do in our daily lives as well — sort through it all and deal with it somehow. A quick look at social media immerses me in the waves: one friend has lost a parent, anther has a new pet, there are fires in Los Angles, new books coming out, the latest scandal or flavor of ice cream. The country is either collapsing or stronger than ever, depending on your point of view. We are inundated.

But if you put down your phone, unless you are in the middle of the turbulence — unless you are fleeing the fires — you return to the relative calm of ordinary life, where not a whole lot is happening at this particular moment. You return to still water. For example, I’m sitting here now, writing about the ocean and the waves, and after that I will need to make lunch, then work on a presentation for a faculty meeting, then continue planning for the semester. Outside it’s cold. The sky is white and there is snow on the ground, as there was last winter. The season moves on at its own pace, and in my own life, the waves do come, but they come much more slowly.

The point I want to make is, it’s so easy right now to feel as though we are swimming among the turbulence, where the waves are the information we receive from all over the world. At least some of the time, to keep from being overwhelmed — from getting salt water in our mouths and eyes — we need to dive down into the still water, let the waves move over us. We need to feel that the ocean is still there, supporting us.

It’s possible that a metaphor is not a good metaphor if it takes so long to explain. But what I want to say is that there are so many waves, but there is also still water underneath. I suggest you dive down into the still water. What is the still water? Well, the passing of seasons, for one. It’s winter now, and eventually spring will come, and that will happen over and over during our lifetimes. It’s a pattern we can hold on to. Another thing we can hold on to is good art. Fashions will come and go, and millionaires will buy fiberglass replicas of balloon dogs, but there will still be museums filled with beautiful paintings. You will still be able to go stand in front of a Monet. And good books will remain. There will be bestseller lists, and categories will have their day, but you will still be able to reach for Jane Austen or L.M. Montgomery. The best authors of my childhood — Ursula Le Guin, Patricia McKillip — are just becoming clear now. It takes a while to see what was truly worthwhile, what lasts.

In retrospect, it was a valuable lesson, learning to swim among the waves. But it’s only recently that I’ve appreciated its value as metaphor, as I’ve felt the turbulence of our times and tried to figure out how to live my own life without being overwhelmed by it. I just have to remember — if you dive down, there is always still water underneath.

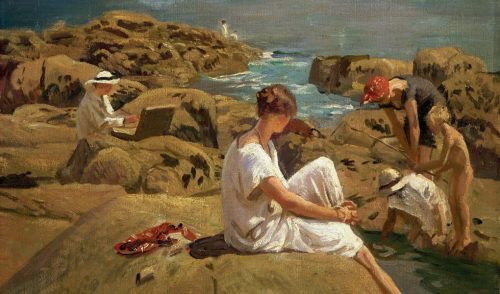

(The image is On the Rocks by Laura Knight.)