Do You Know What Your Dog is Thinking?

Alexandra Horowitz is the author of “Inside of a Dog: What Dogs See, Smell, and Know,” which was No. 1 on the New York Times bestseller list when it was first published in 2009. An updated version has just been released, and she’ll be at the National Book Festival on Sept. 6 to discuss her work. Horowitz teaches at Barnard College, where she runs the Dog Cognition Lab, and has written other books on her canine research.

This conversation has been edited for space and clarity.

Timeless: When meeting a new dog, people will often extend their arm, hand down, to the dog’s nose, instead of reaching out to pet them immediately. Is this actually reassuring to the dog?

Alexandra Horowitz: Well, I think this is an attempt to understand the dog’s point of view, so I understand where it’s coming from. And insofar as it isn’t leaning over a dog and just assuming that they can pat them on the head, it’s an improvement. But it still doesn’t completely take in the dog’s perspective. If I am encouraging somebody who is afraid of dogs on how to greet a new one, I say let the dog decide if they want to come to you. If they want to be petted and they want to meet you, then if you stand with your side to them and not make any aggressive gesture, they’ll come right up to you.

Alexandra Horowitz. Photo: Vegar Abelsnes.

Alexandra Horowitz. Photo: Vegar Abelsnes.Timeless: What is it, in general, that we don’t understand about dogs’ intelligence and how they view us and the world around them?

Horowitz: I think we miss a lot by making assumptions, say, about a dog sitting on the couch with me and thinking they are having the same experience. I guess I’d focus on smell as the thing that has really surprised me, how much it defines who they are and what their capacities are. In smell, we can see that they can distinguish your smell from somebody else’s. They know you by your smell better than by sight. We know that they can recognize themselves by smell and notice when their smell has changed, a kind of self-awareness. They can smell stress in us, actually, and stress is kind of contagious with them. So, the way smell sort of defines their brain, I think is the most intriguing for me and something that there’s really a lot of room to explore.

Timeless: And oftentimes, what we think of as a bad smell is not necessarily what they think is a bad smell, correct?

Horowitz: Oh, absolutely. A lot of my research, and a big focus of this book and my other works, is what it’s like to be a smelling creature experiencing the world because dogs are so profoundly good at olfaction. And one of the things that comes up immediately is just what you mentioned — that we tend to think of smells as kind of good or bad. I don’t think dogs have that kind of impression at all. I mean, there might be a few things that they think are bad smells, but that would be like me saying, “I think of things I see as good or bad.” No, it’s just information about the world. There’s a plant in front of me, here’s a bunch of peaches, here’s a table, there’s a dog. It’s information. What I see through my eyes and what they smell through their noses is similar information.

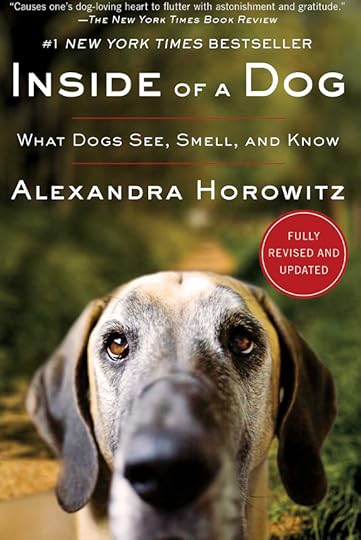

Alexandra Horowitz will be discussing “Inside of a Dog” at the National Book Festival.

Alexandra Horowitz will be discussing “Inside of a Dog” at the National Book Festival.Timeless: You do this in detail in the book, but can you give us a short explanation of how their sense of smell works and how it’s so much wildly better than ours?

Horowitz: I describe it as a sensory parallel universe because I think there are all these smells in the room with me or with you right now, but we’re mostly not experiencing them. Dogs are.

There are so many levels at which they are built to smell. Anatomically, they have these long snouts and can sniff much faster than we can — about seven times a second. That allows them to get a lot more information. Then those odors are sent tumbling down their nose and warmed and humidified to the back of the nose, sort of between the eyes, where there are olfactory receptor cells. They have hundreds of millions more of these cells than we do. This information goes to the brain, where they have a much larger olfactory lobe relative to the rest of their brain than we do. That’s all just on the inhale.

When they exhale, they don’t want to stop smelling, just as we don’t want to close our eyes to see one thing and then the next thing, so they exhale out of the slits on both sides of their nose. This allows them to do a kind of circular breathing. This then ties in with their vision.

I worked on a paper with a group at Cornell [University] in which they used a special kind of imaging to look at dogs’ brains and found that there’s a white matter connection, just like big tracks of neurons, connecting the olfactory lobe to the visual cortex, something that is absolutely not happening in the human brain. So, dogs are probably incorporating what they’re seeing and what they’re smelling instantly, versus how we do it.

Timeless: One of the things you write about is how we anthropomorphize our dogs, which can create misunderstandings. One of these is how we think they’re acting guilty about doing something wrong — an accident on the carpet, say — when they’re actually responding more to our tone of voice and manner.

Horowitz: Yeah, exactly. When I started studying dogs, I was surprised that they hadn’t been a research subject, the way that there is a lot of comparative cognition work on primates and dolphins and rats and mice. And I was like, why aren’t dogs being used? It occurred to me that it was because we kind of think we already have a vocabulary for what dogs know and understand, just from living with them.

I decided to explore empirically whether some of the attributions we make to dogs are correct. And one of the early behaviors I chose was that guilty look that you described: Whereupon being caught having done some misdeed, they turn away or make their body really small, or they do a really fast low wag, or their ears are back. We call that the guilty look because they look guilty, they look like they understand “I did something wrong.”

So, I did an experiment and it turned out that dogs show the most guilty looks when the owner thinks they’ve done something wrong, even if they haven’t. So, the dog is clearly responding to the owner’s behavior. If you come in and treat them like they’ve done something wrong, they’ll learn to put on this basically submissive look.

That’s really different than the dog kind of ruminating about that garbage can they got into three hours ago when the owner was away. The owner is angry that the dog did that, but the dog is not sharing that understanding. Instead, they are very responsive to us. They learn that when we come in looking angry or using an angry tone of voice, they get punished. So, they learn the guilty look, but it doesn’t mean that they are feeling guilt at that moment. I think that’s important. It doesn’t mean that they don’t feel guilt — again, we don’t have access to their interior lives — but it just means that sometimes what looks like guilt to us is something else.

Timeless: Last question. From the dog’s point of view, what do they do when they’re feeling really affectionate and happy toward us?

I don’t know if there’s one thing, but it’s more like a constellation of things which we would recognize. Things like staying close to us or licking in the face. That’s usually done as a greeting, but it’s also sort of a kiss. The excitement they have when greeting us when we return home — a strange dog won’t be happy to see you return, but the dog who knows you and who considers themselves part of your family is delighted. And we all know what that greeting looks like: Tails going bananas, jumping up, ears back and whimpering. It’s something like what wolves in a wolf pack do to each other when they return to their natal group. Dogs do that kind of thing with us.

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free!

Library of Congress's Blog

- Library of Congress's profile

- 73 followers