Is mandatory vaccination intrinsically wrong?

Floridagovernor Ron DeSantis and state Surgeon General Dr. Joseph Ladapo haveannounced that they will be ending all mandatory vaccination in thestate. President Trump has criticized themfor this, saying that “some vaccines… should be used otherwise some people aregoing to catch [diseases] and they endanger other people.” I have long supported DeSantis and have been criticalof Trump, but on this issue Trump is right and DeSantis is wrong.

Floridagovernor Ron DeSantis and state Surgeon General Dr. Joseph Ladapo haveannounced that they will be ending all mandatory vaccination in thestate. President Trump has criticized themfor this, saying that “some vaccines… should be used otherwise some people aregoing to catch [diseases] and they endanger other people.” I have long supported DeSantis and have been criticalof Trump, but on this issue Trump is right and DeSantis is wrong. That is byno means to say that all mandatory vaccinations are defensible. As Ihave argued, the Covid shot should never have been mandatory. But it goes way too far to claim, as Ladapodoes, that all mandatory vaccination as such is “immoral” and amounts to “slavery.” The truth lies in the middle ground positionthat while there is a moral presumption against a mandate, in some cases thatpresumption can be overridden and it can be licit for governments to requirevaccination. Sweeping statements ofeither extreme kind are wrong, and we need to go case by case.

The relevantnatural law principles are straightforward. Human beings are by nature social animals. The primary context in which we manifest our socialnature is the family, but we do so also in larger social orders, and ultimatelyin the state, which, as Aristotle and Aquinas teach, is the only complete andself-sufficient social order. Now, thecommon good of the social order is higher than private goods. As Aquinas teaches, “the good of one man isnot the last end, but is ordained to the common good” (Summa Theologiae I-II.90.3). Again, he writes: “The common good is the endof each individual member of a community, just as the good of the whole is theend of each part” (Summa Theologiae II-II.58.9), and “thecommon good transcends the individual good of one person” (Summa Theologiae II-II.58.12).

By no meansdoes this entail an absorption of families and individuals into some collectivistblob. The natural law principle ofsubsidiarity requires as a matter of justice that central authorities do notinterfere with lower level social orders (such as the family) when the latterare capable of providing for their own well-being. At the same time, subsidiarity also requiresthat central authorities do step inwhen a social order at some level cannot,on its own, secure its well-being. Andsuch authorities can compel citizens to do what is necessary for the commongood when there is no other way to achieve it.

For example,as the traditional Thomistic natural law theorist Thomas Higgins writes: “Note laws of compulsory military service. In time of war or grave danger of war theyare gravely binding because they then express the Natural Law commandingcitizens to preserve the State” (Man asMan: The Science and Art of Ethics, p. 520). This is so even though, as Higgins goes on toacknowledge, such laws can under some peacetime circumstances be contrary to thecommon good. He even argues that acitizen could in such a case licitly try to avoid being drafted, as long as hedoes not use immoral means to do so.

This exampleillustrates a point the importance of which cannot be overstated. To say that the state has a right under somecircumstances to compel certain behavior simply does not entail giving it ablank check to do with citizens whatever it likes. That is a straw man to which too many aredrawn today, because of the individualism and excessive hostility to authority thattends to characterize American politics on both the left and the right.

In any case,the general principle stated by Higgins has also been expressed by themagisterium of the Catholic Church. Oflaws requiring military service during a national emergency, Pope Pius XIItaught:

If, therefore, a body representative of the people and agovernment – both having been chosen by free elections – in a moment of extremedanger decides, by legitimate instruments of internal and external policy, ondefensive precautions, and carries out the plans which they consider necessary,it does not act immorally. Therefore aCatholic citizen cannot invoke his own conscience in order to refuse to serveand fulfill those duties the law imposes. (Christmas message of December 23,1956)

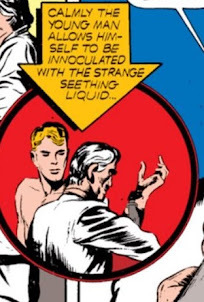

Now, ifthere can be circumstances wherein the state can licitly compel citizens torisk dying in battle for the sake of the common good, then it follows a fortiori that there can also becircumstances wherein the state can compel citizens to be vaccinated for thesake of the common good. In both casesthe end is the same, namely to prevent the deaths of large numbers of one’scountrymen. And in the case ofvaccination, the risk to the individual who is compelled is less serious thanthe risk imposed on those drafted into military service.

The Churchherself has indicated that it can be licit for states to requirevaccination. As Roberto de Mattei hasnoted, “on 20 June 1822, in the Papal States, the Cardinal Secretary of State,Ercole Consalvi, issued a decree which instituted a Central VaccinationCommittee for inoculation throughout that territory” (On the Moral Liceity of the Vaccination, p. 55). In 2005, during the pontificate of PopeBenedict XVI, the Pontifical Academy for Life saidthe following about the benefits of universal vaccination:

The severity of congenital rubella and the handicaps which itcauses justify systematic vaccination against such a sickness. It is very difficult, perhaps evenimpossible, to avoid the infection of a pregnant woman, even if the rubellainfection of a person in contact with this woman is diagnosed from the first dayof the eruption of the rash. Therefore,one tries to prevent transmission by suppressing the reservoir of infectionamong children who have not been vaccinated, by means of early immunization ofall children (universal vaccination). Universalvaccination has resulted in a considerable fall in the incidence of congenitalrubella.

The documentgoes on to note that when parents refrain from vaccinating children againstGerman measles, there is

the danger of Congenital Rubella Syndrome. This could occur, causing grave congenitalmalformations in the foetus, when a pregnant woman enters into contact, even ifit is brief, with children who have not been immunized and are carriers of thevirus. In this case, the parents who didnot accept the vaccination of their own children become responsible for themalformations in question.

OrthodoxCatholic moral theologians have thus defended the liceity of requiringvaccination, when this is necessary for the common good. In their book Life Issues, Medical Choices: Questions and Answers for Catholics,Janet Smith and Christopher Kaczor note that “vaccines have virtuallyeradicated some childhood diseases common in decades past, such as polio,measles, tetanus, smallpox, whooping cough, and diphtheria” (p. 154). And they observe that when parents haverefused these vaccines for their children, the result has sometimes been arecurrence of such diseases. Theyacknowledge that vaccines carry some risk, and that there can be cases whereexemptions are reasonable. But nevertheless,they argue:

Rather than risk the outbreak of a disease that could kill orseriously harm many, individuals are reasonably expected to undergo somepersonal risk. In order to reduce risksfor the whole community – especially those who are particularly susceptible toharm, such as children too young to be vaccinated and those who cannot bevaccinated for health reasons – it is reasonable and just for otherwise healthymembers of the community to submit themselves to the small risks of vaccines…The Church teaches that we are all members of the body of Christ and that weare brothers and sisters in the Lord. Thus, we all have a serious obligation to seek the common good andsometimes to put ourselves and our children at some reasonable risk for thewell-being of others. (pp. 153-54)

In recentdays, some on Twitter/X have nevertheless claimed that the Church teaches that vaccinationcannot ever be mandatory. One argumentalong these lines appeals to the following statement made by Pope Pius XI in CastiConnubii:

Public magistrates have no direct power over the bodies oftheir subjects; therefore, where no crime has taken place and there is no causepresent for grave punishment, they can never directly harm, or tamper with theintegrity of the body, either for the reasons of eugenics or for any other reason.

But thisdoes not entail that vaccination can never be mandatory. For one thing, Pius was not addressing thequestion of vaccination in this passage, but rather the topic of forcedsterilization and other bodily mutilations. Vaccination does not involve mutilation of the body, so inferring fromhis remark that mandatory vaccination is illicit is simply a non sequitur. For another thing, the argument would provetoo much. You might as well say thatPius XI’s remark absolutely rules out ever forcing citizens to serve in themilitary. But that would contradict theteaching of his successor Pius XII, which I cited above.

Anotherargument appeals to the2020 statement from the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith onCovid-19 vaccination, which says that “practical reason makes evident thatvaccination is not, as a rule, a moral obligation and that, therefore, it mustbe voluntary.” But there are twoproblems with this argument. First, itignores the fact that this document is not addressing the morality ofvaccination in general, but only the morality of Covid-19 vaccination inparticular. The reason is that many Catholicswere concerned that the Covid vaccines were linked to fetal tissue research ina way that made them morally problematic. The point of the document was to inform Catholics who were inclined totake the vaccine that they could do so in good conscience, while at the sametime making it clear to those who were uncomfortable with doing so that theywere not obligated to do so. All of thisis clear from the larger immediate context of the line quoted above:

Both pharmaceutical companies and governmental healthagencies are therefore encouraged toproduce, approve, distribute and offer ethically acceptable vaccines that donot create problems of conscience for either health care providers or thepeople to be vaccinated.

At the same time, practical reason makes evident thatvaccination is not, as a rule, a moral obligation and that, therefore, it mustbe voluntary. In any case, from theethical point of view, the morality ofvaccination depends not only on the duty to protect one's own health, but alsoon the duty to pursue the common good. In the absence of other means to stop or evenprevent the epidemic, the common good may recommend vaccination, especially toprotect the weakest and most exposed. Thosewho, however, for reasons of conscience, refuse vaccines produced with celllines from aborted fetuses, must do their utmost to avoid, by otherprophylactic means and appropriate behavior, becoming vehicles for thetransmission of the infectious agent. Inparticular, they must avoid any risk to the health of those who cannot bevaccinated for medical or other reasons, and who are the most vulnerable.(Emphasis in the original)

Note thereferences to “the epidemic,” “vaccines produced with cell lines from abortedfetuses,” and the encouragement of pharmaceutical companies and governments toproduce alternatives “that do not create problems of conscience.” What the document is addressing is whether the vaccines that were developed in order todeal with Covid-19, specifically, ought to be mandatory.

Moreover,the CDF statement does not actually say even that Covid-19 vaccination absolutely must in every case bevoluntary. What it says is that “vaccinationis not, as a rule, a moral obligationand that, therefore, it must bevoluntary.” The claim is that as a rule (in other words, in general)it is not an obligation. But that leavesit open that there could nevertheless be particularcases where it would be a moral obligation (for example, for hospital workers,perhaps). And it leaves it open that in those particular cases vaccinationshould be mandatory rather than voluntary. But again, the CDF document is in any case addressing the Covid-19situation in particular rather than vaccination in general. So it is not inconsistent with the point I’vebeen making.

I hasten toemphasize that that point is a very narrow one. I am arguing here only that the extreme claim that mandatory vaccinationis always and intrinsically wrongcannot be justified on grounds of natural law theory and Catholic moraltheology. That does not by itself showthat any particular vaccine mandate is a good idea, all things considered. One has to go case by case and make a prudentialjudgment based on the relevant empirical evidence. But appeal to simplistic slogans like “Mybody, my choice” can provide no short cut.

Edward Feser's Blog

- Edward Feser's profile

- 323 followers