Theodora Goss's Blog

September 4, 2025

Creating a Writing Life

I have four months.

Sometimes I envy people who just write. They can get up in the morning, get in their writing, do the other things they need to do — write to agents and editors, work on publicity, etc. All the business of writing. They can focus on one thing. I, on the other hand, teach at a university, so I spend a lot of my time being a university professor. I plan for and teach classes (both discussions and lectures), grade essays and presentations, meet with students, and of course serve on committees. There are aspects of this job that I do all year round — the committees never go away, for example. But I’m exceptionally lucky in my teaching schedule. In my program, which I love, I teach for four months of the year in Boston, and then two more months in London. While I’m teaching, it’s an intense schedule, particularly in London — we teach an entire semester in that is essentially half a semester. There are days when I leave my London apartment at 8 a.m. and return home at 8 p.m. But I do love teaching.

The other six months of the year, my teaching work continues, but I’m not in classes or with students. That means I have time to do the other thing I’m supposed to be doing (according to me and the universe), which is write.

This year, I taught in Boston from January through April, then in London from May through June. July and August were complicated — there were other things I needed to take care of, family obligations I needed to fulfill. But now it’s September, and I have four months until I need to teach again. Now, it’s time to write.

The problem, of course, is that I’m not using to just writing. I’m not even sure how people who just write do it. So I need to create a writing life for myself, in which I both write and take care of the business of writing. That business is particularly important right now, because I have a short story collection coming out in November. Of course I’m nervous about it, because I don’t know what people will think or how it will be received. I suspect that people who like my writing will like it, and people who don’t like my writing won’t, which is about usual. But I’m tremendously proud of it, particularly because I really wanted Jo Walton to write the introduction, and she did, and I really wanted a cover by Catrin Welz-Stein, and I got that too, and on top of all that, I really wanted the publisher to be Tachyon Publications, which is a truly excellent press. And I got that as well. So this book is a kind of present to me — thank you, Seshat, goddess of writing.

So what should I do for the next four months? I have a goal, which is to finish the novel I’ve been working on. It’s a novel-length version of a short story I wrote many years ago called “Pip and the Fairies,” and if you’re curious, you can read the story online. I’m about halfway through the novel manuscript, and four months should be enough to finish. But of course I also have a short story collection to publicize, and various smaller projects to complete. I’ve promised a poem to one magazine, an essay to another. I will lead a workshop, give a talk, attend the World Fantasy Convention. And of course, I still have teaching work to do — I’m meeting a student later today to help with a scholarship application. And I would like to keep up a regular schedule of blogging, because this is important to me personally and intellectually — it’s only when I write about something that I know what I think about it.

(Someone once advised me not to write blog posts, and to put that energy into my short story and novel writing instead. I tried that, but got almost immediately blocked up, like a clogged sink. It turns out that blogging — putting my thoughts on screen — helps keep my writing pipes clear. I can get my random thoughts out, rant all I want to on my website or social media, and that allows the creative material to come through more clearly.)

When thinking about how to arrange my writing life, I went to the oracle: Ursula K. Le Guin. She famously once wrote that her ideal writing day included waking up at 5:30 a.m., eating breakfast at 6:15 a.m., and then starting to write at 7:15 a.m. She would write until lunchtime, and then the rest of the day would be taken up with reading, correspondence, housecleaning . . . I could not get up so early, because I don’t go to sleep at 8:00 p.m., as she seems to have done. But I think the central idea here is to choose a time of day that is your writing time, and then use it to write. I know, it sounds quite simple, but it’s harder to actually do — there are so many things that take our attention away from writing. Today, for example, my day started with a dental appointment. Even writers have to get their teeth cleaned.

I also looked up Stephen King’s writing routine, and found this quotation online: “I wake up. I eat breakfast. I walk about three and a half miles. I come back, I go out to my little office, where I’ve got a manuscript, and the last page that I was happy with is on top. I read that, and it’s like getting on a taxiway. I’m able to go through and revise it and put myself — click — back into that world, whatever it is. I don’t spend the day writing. I’ll maybe write fresh copy for two hours, and then I’ll go back and revise some of it and print what I like and then turn it off.”

It’s essentially the same idea: find a time to write, about four hours he says elsewhere, and then sit down and write. And do that every day, so it becomes a habit.

So that’s my plan, essentially. It’s very simple. I have four months, and my plan is to write every day, for at least two hours — and even better if I can get in three or four. And of course to take care of the business of writing, because I’m the one running this business, but I’m also the only one making this business run, and the convention hotel won’t reserve itself. If I’m lucky, with the teaching schedule I have now, I will have several months year to just focus on writing. I’ll still envy writers who can do it full-time. That’s a very different existence than the one I have. But I’m grateful for the time I do have, and if I use it well, I hope to create wonderful things. Praise Seshat.

(The image is a photograph of a relief of the goddess Seshat on the Amun Temple at Luxor, taken by Jon Bodsworth.)

August 17, 2025

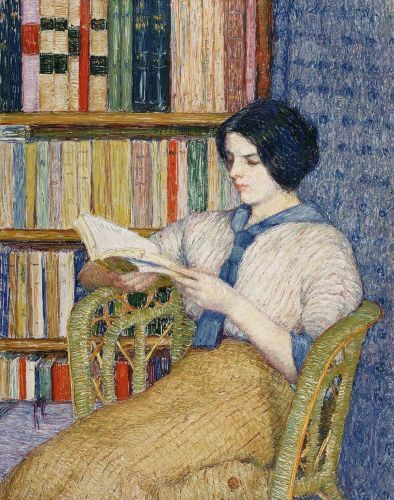

The Book and the Wardrobe

In the last few days I’ve been reading Breakfast at Tiffany’s, which is about as far from The Chronicles of Narnia as one can get, although Holly Golightly would make a very good White Witch, tempting Edmund with Turkish Delight and probably vermouth. But reading Truman Capote’s novella made me think about how every book — at least every good book, and perhaps even a not particularly good one — is a wardrobe, which makes it both enchanting and dangerous.

You probably remember what happened to Lucy, Edmund, Susan, and Peter when they went through the wardrobe? First, they entered an enchanted (and enchanting) country, where the animals could talk. The most important of those animals was Aslan, the great lion. The four children had adventures and participated in battles, but in the end it was Aslan who defeated the White Witch — only Aslan could do so. He saved Narnia, and Peter, Susan, Edmund, and Lucy ruled as kings and queens in Cair Paravel by the sea. Meanwhile, Aslan came and went as he wished. The four children grew up in Narnia, then were pulled back into their own country and became English school children again. Although they spent years in Narnia, in our world it seemed as though only minutes had passed. In a later book, we are told that time works differently in Narnia and our world — it could work the other way around as well, with minutes passing in Narnia and aeons in England.

We know that the tale of The Lion, the Witch, and the Wardrobe is a religious fable of sorts, with Aslan as a Narnian Jesus, but can you see how it’s also (and perhaps even more fundamentally) an allegory for the act of reading itself? Entering the wardrobe is like entering a book. You have all sorts of adventures there, and everything within the book is alive — it speaks to you, even if it might not speak in our world. It is all text, and therefore it’s all talking in your head. Here is how Breakfast at Tiffany’s starts:

“I am always drawn back to places where I have lived, the houses and their neighborhoods. For instance, there is a brownstone in the East Seventies where, during the early years of the war, I had my first New York apartment. It was one room crowded with attic furniture, a sofa and fat chairs upholstered in that itchy, particular red velvet that one associates with hot days on a train. The walls were stucco, and a color rather like tobacco spit. Everywhere, in the bathroom too, there were prints of Roman ruins freckled brown with age. The single window looked out on a fire escape. Even so, my spirits heightened whenever I felt in my pocket the key to this apartment; with all its gloom, it still was a place of my own, the first, and my books were there, and jars of pencils to sharpen, everything I needed, so I felt, to become the writer I wanted to be.”

The items listed by the narrator don’t themselves speak within the story, but they are spoken. As you read, you hear a voice in your head, describing the sofa and chairs upholstered in itchy red velvet. You hear, or at least I do, the k-sounds in stucco and tobacco, and there is something particularly visceral at the end of that sentence with the s-p-i-t of spit. Your mind almost spits it out. For me, at least, it’s as though everything in the paragraph is speaking — not just the narrator, but the walls of the apartment themselves. Everything becomes meaningful. I have entered an enchanted country. (By the way, I am drawing here on the theories of David Abrams on how text functions — how it becomes animate in our heads as we read. You can find out more in his book The Spell of the Sensuous, especially the chapter “Animism and the Alphabet.”)

While I am in that country, I forget time is passing in my world, although the clock keeps ticking. In reading, I myself become timeless — subjectively, I step out of chronological time for a while. And yet time passes within the story as well. The narrator describes his own past, when he knew Holly — at the time he is writing, she is somewhere else in the world, perhaps in Africa but who knows. The narrative itself takes place over a number of months. So there I am, sitting in bed, propped against my pillows, reading a book, and time is going all wonky — it’s passing in my world, but I don’t feel as though it’s passing, and it’s also passing in the story, but differently than in my world, and temporarily at least, I am living those months with Holly Golightly. I am in Narnia, on the East Side of New York, during the lean years of the Second World War. (Funnily, I never thought about the fact that the Narnia books and Breakfast at Tiffany’s are connected in that way — they both take place during wartime. Holly is about the same age Susan grows up to in Narnia. C.S. Lewis would not have let Holly back into Narnia either.)

In the enchanted Narnia of the book, I have a guide who leads me through the narrative, telling me where to go and what to think. That guide may be reliable or unreliable — in The Lion, the Witch, and the Wardrobe, my guide is initially Mr. Beaver, but then it becomes Aslan himself. In Breakfast at Tiffany’s, it’s the unnamed narrator. But Aslan is more than a guide. He is the son of the Emperor-over-the-Sea, who is God, but also the Author. Can you see how and why? Aslan is more than a character within the book — he also writes its plot. In a sense, he is an extra-narrative force that steps outside the parameters of the story to actually create it. He invokes the laws of Deep Magic established before the dawn of time, before narrative began. And with them, he changes the story. If we return to the religious fable, he is God in the way that Jesus is also God, and remember that God is an author. He creates the world through the Word. Lewis’s pal J.R.R. Tolkien made this point in “On Fairy-stories” when he said that God is a creator and the writer is a sub-creator; writing is a sub-creation that mirrors the original creation.

When Lucy and her siblings step through the wardrobe, they enter a magical country created by an Author. They enter a story in which they participate, during which all sorts of things happen to them, including winning a battle, becoming kings and queens, and even growing up. Then, they are whisked back to through the wardrobe into their own ordinary realities. They are the same yet different. The Author brings them back to that country again — in the next book. Going to Narnia is analogous to reading.

When you were a child, did you try to find the wardrobe? Did you test the back of every wardrobe you saw, just to see if it might lead you to Narnia? I certainly did. My argument here has been that every book is a wardrobe. It functions just like the one in The Chronicles of Narnia (and like that wardrobe, sometimes it works, sometimes not). The best books, and some not very good ones, are deeply immersive experiences. They are enchanted and potentially dangerous, because they might change you permanently — that is why people keep trying to ban them. Do you remember the most magical place in the entire Narnia series? It was the Wood Between the Worlds in The Magician’s Nephew. From there, you didn’t need a wardrobe — you could travel into any world at all. After a childhood of testing wardrobes, it is reassuring to me, personally, to think that I have an entire Wood Between the Worlds right on my bookshelves.

(The image is Woman Reading by Torajiro Kojima.)

August 9, 2025

In Praise of Modesty

When I was in sixth grade, I had a French teacher called Madame. All French teachers are called Madame, unless they are called Mademoiselle, and the Madames are scarier. I’ve never had a French teacher that I did not find mildy terrifying.

This particular Madame was actually French. Every day, she wore a sensible skirt whose hem brushed the bottom of her knees, and the sorts of sensible heels that older European women wear, and her gray hair was tucked into a sensible but still elegant bun. She looked quite different from our other younger, more casual, American teachers.

One day, she asked all of us to stay after class. We were all girls — it was not sufficiently masculine, in sixth grade, to learn French. And she gave us a lecture on how to sit. First, she placed one of the wooden chairs at the front of the class. Then, she splayed in it, the way we, jeans-clad sixth graders, splayed in our chairs. And then she told us it was not elegant, that we looked sloppy. And she sat up properly. She showed us how to sit.

This may sound rather silly — an old French woman teaching a class of sixth-grade girls how to sit. But the lesson stayed with me. It was not about modesty in the traditional sense of keeping your knees together, although sitting properly did involve an appropriate placement of the knees. It was about having a kind of ease and elegance and simplicity in your movements. A kind of appropriateness.

I was reminded of this lesson recently in Vienna. There were some ostentatious buildings, of course — the Hapsburgs were nothing if not ostentatious. But there were no skyscrapers in the central city. The architecture felt eclectic, with its ancient apartments and modern cafés, but it still felt whole, as though all parts of it belonged to a single body. Budapest feels even more like that to me, but of course Budapest has official height restrictions for every building except the MOL tower, which was built before the height restrictions came into effect. (Buildings in Budapest can’t be higher than 96 meters — the height of St. Stephen’s Basilica.) The MOL tower sticks up like a clichéd thumbs-up sign. Visually, it resembles a sixth-grade girl with her leg sticking out into the aisle, where you can trip over it. On the skyline of Budapest, your eye trips over the MOL tower. It’s the most immodest building in Budapest. Predictably, MOL is an oil and gas company.

We are living in an age of immodesty that has nothing to do with wearing short skirts, and everything to do with showing off your shopping haul from the latest fast fashion retailer. With consuming too much, thoughtlessly. With ostentation for its own sake. (The Hapsburgs were guilty of this too, of course. As I walked through the Kunsthistorisches Museum, I passed through room after room of their golden tchotchke. It was like eating a dinner of nothing but petit fours — endless fondant, so sweet it makes your teeth hurt.) We are living in the age of starchitecture, of couture gowns that can’t be worn off a runway or red carpet. (Everyone has phones with video, so we can all see actresses trying to sit in their Oscar or Golden Globe gowns, tilted in their chairs like see-saws, not even pretending to eat.) It’s the age of “drill baby drill,” when maintaining our extravagant lifestyles is more important than the environment. The age of chefs creating expensive dishes that are barely food — and, on the other hand, supermarket aisles filled with colorful items that are definitely not food. Perhaps the innovation of our age is that Hapsburg-level waste is no longer confined to the Hapsburgs. We can all have homes filled with the latest things that no one actually needs, but instead of endless porcelain shepherdesses we have Labubus.

I will be the first to proclaim myself guilty. I recently counted the skirts in my closet, and I have thirty-three. Those are only the summer skirts. Clearly, it’s time for a personal Mari Kondo moment, and perhaps I should not be writing a post on modesty, from my own position of immodestly owning seven pairs of Keds on two different continents. I acknowledge the beam in my own eye. But I still want to say — we need to rethink the way we are living. In the United States, in particular, we are in danger of creating another gilded (rather than golden) age, where the White House begins to resemble the Hofburg, with its Baroque gilding, and where the wealthy get most of the spoils. The difference, in our twenty-first century, that the poor also get spoils — cheap plastic spoils. They are even promised their own AI servants, who lie and manipulate just as real servants probably did in the eighteenth century. And the things that are natural, simple, appropriate, are not valued.

So what is modesty? I think it’s listening to the sounds of birds. Of growing a garden and allowing the insects to flourish, even as you net your raspberries. Of realizing that diamonds are just hard rocks and designer clothes are made in the same factories that manufacture for Target. Of knowing there is such a thing as enough — in Keds, in yachts (the number of enough yachts is none), in educational theories as well as in foreign policy. How do you define enough? I think you do it by developing a kind of good taste, a sense of appropriateness and elegance. What is an elegant building — one that reflects the needs of its users, not the ego of its designer? What is an appropriate dress — one that fits the person who will wear it and the occasion on which it will be worn? What is easy to live in, move in? These seem like simple questions, but they are fiendishly complicated — philosophers have been trying to define good taste since around the time the Hapsburgs became the it-royals of Europe.

One fundamental problem of our economic and political system is that we don’t actually need most of the things we have, so the system, to perpetuate itself, has to make us want more. We have to, somehow, learn what is enough.

That’s what I mean by modesty. And we need it pretty desperately, in political life as well as in our shopping habits. Perhaps it begins with the body itself — how do we sit, how will we move, what will we do today? Will we listen to the birds? Will we walk in the city, among the beautiful old buildings? (I will — but then, I’m in Budapest.) And then it extends outward. What will I buy? Which services will I use? Who will I vote for?

I know this post is itself a bit Baroque, curling all over the place. What I want to praise is a kind of life in which we plant gardens and write poems and paint pictures. In which we listen to concerts in churches and under the trees in city parks. In which we admire the moon in her phases. In which butterflies are more important than the latest cheap plastic toy. Maybe even one in which cathedrals are taller than financial buildings, although that’s asking for a lot in this intensively capitalistic age. In which old French women with buns of gray hair sit elegantly, preferably by a river, preferably with a croissant and a cup of hot chocolate. I hope the Madames know, in some way, that we still remember them.

(The image is Butterflies by Odilon Redon.)

July 17, 2025

From London to Budapest

I left my apartment in London (paid for by the university) in an Uber (paid for by the university) and flew on British Airways from Heathrow to Liszt Ferenc Airport (paid for by you know the drill). And then I took a bus (paid for by me) to my apartment in Budapest (passed down from my grandparents to my mother and then to me). And now I sit in the living room where I played as a child, looking out the window at the trees in the park around the Nemzeti Múzeum, where my grandmother used to take me.

The apartment in London had looked out at trees as well. From the living room you could see the treetops along a small road of elegant white houses, the kind that populates Kensington. (I’ve been told you’re not allowed to paint the houses any other color there.) From the bedroom you could see the treetops of Kensington Gardens. It was not a large flat — just two rooms, plus the kitchen and bathroom, and even the kitchen was sort of a half-kitchen, with a half-sized refrigerator and just two burners on the stovetop. But of course it was expensive, much more than I could ever have afforded myself. Once you emerged from the small street on which it was situated, you were in the bustle of High Street Kensington. I enjoyed that bustle — while I was in London, that is.

Budapest was a bit of a shock, after London. In previous years, I’ve come here from Boston, which even on its most bustling day is a sleepier town than London. But where I live in Boston is quiet and leafy and not at all crowded. Boston to Budapest is less of a shock to the system than London to Budapest, and for about a week I could not slow down. I was rushing here and there. Of course, it did not help that I had to finish final grading for the summer semester — I would read travel journals, then go grocery shopping at Spar, then watch video essays, then run to DM or Rossman before it closed. In London I had shopped at Sainsbury’s and Waitrose, or Boots for things like toothpaste and shampoo, and when I had rushed, it had generally been to class or one of our excursions.

But here in Budapest, sometime after I finished grading, I started to slow down. I realized that no one else was rushing around. People were strolling, sitting in cafés, talking to one another. I wasn’t in London anymore.

It’s hard to describe the difference between London and Budapest, because it’s almost as though they exist on different planets. The current population of London is almost nine million people. The current population of Hungary is about 9.5 million people. In other words, the entire country of Hungary has slightly more people in it than the city of London. About 1.7 million of those people live in Budapest. Boston, if you count all of it (including areas like Cambridge that are Boston by another name), contains around 4.3 million people. So it’s more than twice as populous as Budapest. It also exists on another planet — the planet of countries that were not bombed in either world wars. I’ve written about that distinction elsewhere, so I won’t talk about it here, except to say that when my students fly from Boston to London, they feel as though they’ve arrived somewhere ancient and consequential, in part because it bears the scars of those war years. And they’re right — there is a significant shift even between Boston and London. But the honest truth is that the two cities don’t feel that different to me.

I mean, not as different as traveling from either of those places to Budapest.

The first week, I was too rushed, and also too sick from a virus I had brought with me from London, most likely caught from the students and exacerbated by the cool, damp weather of a London summer. Slowly, the dry heat of Budapest began to vanquish the virus. Once my final grades had been uploaded, I began to slow down. I walked more slowly down the street. I moved more slowly around the apartment. Even my thoughts began to slow down.

I suppose the process had begun, even if I wasn’t conscious of it, when I landed at Liszt Ferenc Airport, which has only two terminals. It continued on the bus ride to the city center, which sped through areas of old factories, now rusted, and small suburban houses, their yellow or orange or pink paint peeling. Or sometimes the houses are mint green, or a kind of brownish red, each house situated in its small garden. And then we were in the city, where the buildings are just as colorful, some fully renovated, some still with cracked paint exposing the underling plaster or covered by layers of soot from the era of Trabants. And then we arrived at Kálvin tér, which is a busy intersection but nothing at all like Piccadilly Circus. And I climbed the stairs to what I still think of as my grandparents’ apartment.

Now I am here until almost the end of August. I’ve finished all of my work for the semester and I’m back to working on writing. I suppose it’s good to be in Budapest to write, because writing takes going slowly — it takes immersing yourself in a way that you can’t when you’re skimming over the surface of life. I did write a few poems in London — I could do that. But now I need to work on stories and a novel, and for those things, I need to concentrate, to dig down deep into things. Into myself of course, but also into the world. It’s as though the imagination is a shovel, and I need to dig into the soil of reality — of what happened in the past, of what people are like in the present. That is, into history and psychology. And I need to dig deep into the language as well, into words and their etymologies and the ways in which they do or don’t go together. I wonder if that makes me a gardener or an archaeologist? I suppose a writer needs to be both, to dig in order to find things but also in order to grow things.

Can I find things and grow things here in Budapest? I hope so . . .

(The image is View of Budapest by Albert Gleizes.)

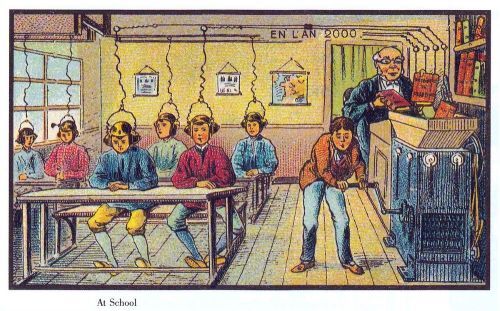

June 14, 2025

Teaching in the Age of AI

I’ve been thinking a lot about teaching in the age of Artificial Intelligence. I think all teachers have to now, because our students are clearly using AI applications like ChatGPT to help with their homework — or do their homework. My colleagues have various attitudes toward AI, and have come up with approaches based on those attitudes. Most of them don’t want students to use AI, and explicitly tell students not to use it. But the students do use it — obviously or not so obviously. In response, some teachers have gone back to using paper tests and timed essays handwritten in class. Of course, there are also teachers who are enthusiastic users of AI themselves, and they explicitly incorporate AI into their classes. For example, their students might be asked to write an essay using AI, then revising that essay as a way of learning what sorts of mistakes AI habitually makes and how they can use AI effectively.

I’ve opted for a sort of middle approach, and I thought I would write about it in case my thoughts on this issue might help anyone else. But I’m not sure my approach is the right one. I describe it here in case you find it useful. I will have to evaluate whether it’s useful myself as I continue teaching.

First, let me tell you about my teaching. I’ve taught many things over the years — if you count the classes I taught during graduate school, I’ve been teaching for about twenty years now. My current role is as a teacher of rhetoric, which basically means communication. We start by talking about oral languages, then cover classical oratory, the transition to written systems of communication, the rise of the essay as a literary form, the advent of visual communication in advertising and political propaganda, the invention of photography and film . . . Basically, I take my students from the start of human communication to where we are now, with AI, and then back around to how AI is helping us understand where we all started — with animal languages. It’s a fascinating topic, and one I love to teach because I’m constantly learning, constantly reading up on new theories, new discoveries. Recently, I’ve been reading articles and listening to podcasts on AI. There are new developments every day, and a great deal of disagreement about what AI will do — save the world, destroy it, or a variety of scenarios in between.

My students don’t think about their use of AI so deeply. They see that their friends are using ChatGPT, so they start using it themselves — not all of them, and some students are adamant about not using AI. But some of them are certainly using it, for various purposes. So what have I decided about the student use of AI?

Here’s the policy I adopted earlier this year:

In this course, you may not use generative-AI tools such as ChatGPT to write or revise text in your assignments. Your writing must be your own. You may use AI-based tools to help you understand readings, brainstorm ideas, check grammar and spelling, and assist with translations, as long as the AI tool is not brainstorming, translating, or proofreading instead of you. Even if you use AI to help you understand difficult passages, you are still responsible for reading, completely and with attention, all of the assigned texts.

Then I tell students they must do two things:

Before they use any AI tools, they must (1) watch an article on how AI impacts people in much poorer counties who are paid very small amounts of money to train AI and (2) read an article on how much water AI uses. I want them to be aware of AI’s ecological and societal impact.With their assignment, they must include a note disclosing whether or not they used any AI tools, including grammar checkers and bibliography generators.Do they do these things? The conscientious ones do at least some of them.

My policy goes on to say:

Remember that whatever tools you use to create your assignments, you are the one responsible for turning in thoughtful, interesting, and insightful work. Any errors produced by AI tools that you do not correct will impact the quality of your final draft, and therefore your grade. Use these tools carefully, conscientiously, and ethically, with awareness of their environmental and societal impact.

My goal with this policy is to let students know that they are allowed to use AI (because I think they will use it anyway), but also to make clear that they are responsible for their use of AI. Here is the sort of thing I repeat over the course of the semester:

“Remember that in this class, you’re allowed to use AI, as long as you follow the policy. However, if you’re writing in a way that sounds vague and clichéd and mechanical, you will lose credit, and it doesn’t matter whether ChatGPT wrote it or it’s your own original writing. You need to write in a clear, specific, interesting way, no matter how you do it. You are responsible for your writing. In the end, you will be the one getting a grade, not ChatGPT.”

I also tell them that the worst offenders in terms of mechanical writing — specifically writing flagged by AI checkers — are professors, because so many of them have been taught to write like machines. (This is backed up by research — as well as the experience of colleagues dismayed when they put their own original, carefully researched articles into AI checkers, only to find that it was flagged as almost completely written by AI. This is why I would never use AI checkers for student writing.)

So much for the policy, but what about the actual assignments? I don’t want to go the route of colleagues who are asking students to write on paper. I think that’s a perfectly legitimate route, and it may even be good for students to practice writing manually. I know that I think differently when I write by hand and when I write on a screen. We should not lose what manual writing gives us. But I’ve taken a different approach. Instead, I’ve tried to design assignments that students can’t do by simply plugging them into AI — assignments in which they have to exercise agency and creativity. Here’s an example:

Our first assignment this semester is a photo essay focusing on a specific location. This assignment has a number of steps. First, the students must write a one-paragraph proposal, which I comment on. Then, they must take 10-12 photos and create a storyboard in which they describe both the design elements in each photo (for example, what angle they took the shot from and why) and the sequence in which they want to present their photos. I look at each storyboard and give feedback. Then they must write a draft script for their photo essay, which again I comment on. The final step is to put the photos together with the script to create a photo essay — one that incorporates both text and photos in a way that is more powerful than either the text or photos individually. The photo essay includes a title, captions for the photos, and a Works Cited.

I didn’t design this assignment with AI in mind, but now that we are in the age of AI, here are the basic principles behind this assignment that might help minimize (or at least complicate) student use of AI:

The students can choose which location to focus on (a park, a museum, a market, etc.), and they have to incorporation themselves into the essay (“When I entered Hyde Park, the first thing I noticed was . . .”). They are asked to make choices and incorporate their own experiences and responses. The assignment requires some level of creativity, agency, and introspection.The assignment has a number of steps, and I comment on student work at various stages. At any point, I can say, “This sounds vague–could you be more specific?” or “Could you put more of yourself into this analysis? What did YOU think when you entered the park?” The steps also require students to do different things — propose, analyze, research, synthesize, etc.The assignment has experiential and visual components, so that even if students wanted to plug a prompt into ChatCPT (and they would have to write the prompt, because I don’t provide one — really, their proposal is the prompt), they would still need to visit the location, take the photos, etc. At a minimum, if they were committed to using AI, they would have to use several different AI tools.The assignment does not have a “correct” answer. It asks students to choose a location and show the reader something about that location the reader would not otherwise notice. That could be something about its history, about how it’s used, about the communities that inhabit it . . . So there is no “right” way to do this assignment. It’s about observing, analyzing, researching, and finally revealing.I don’t know if I’m doing this right — it’s possible that a student could do this assignment without going to the location, taking the photos, etc. And the technological landscape is changing so fast that we don’t know how AI will be used, or how we will be teaching, even a year from now. But I offer this as one possible way of thinking about teaching in the age of AI — and I’m eager to learn about what other teachers are doing, at least until we are all replaced by ChatGPT. Which will hopefully not be next year . . .

(The image is from In the Year 2000 (En L’An 2000), a French series of postcards produced around 1900 hypothesizing what education would look like in the future.)

June 1, 2025

Making a Home in London Again

One of the greatest pleasures in the world is waking up to the sound of birdsong.

That’s what I wake up to each morning in my London flat. It’s not really my flat, of course. Someone else owns it, and I am only its temporary occupant, courtesy of the letting company that lets it out to short-term tenants and the university that pays for my stay here. This is the fourth flat I’ve had in London. The first was quite far from the central campus — I had to find it in a hurry when I was asked to replace a faculty member who could not come to London after all. It was in the north of London, on a charming street, and would have been perfect if not for the long commute. The second was in Kensington, within walking distance of campus, and quite posh — but several things went wrong with it. When I moved in, the refrigerator was already broken and needed to be replaced, for example. There was also the fact that it was close to a rather noisy pub, where a crowd would gather on Friday and Saturday evenings. The third flat was in a quiet back street several blocks from Sloan Square. It was a basement flat, which is perfect for July in London, where most flats have no air conditioning. I loved it and wanted to return this summer, but the university changed my schedule — I would be teaching in June, not July — and that flat was already reserved by someone coming for the Chelsea Flower Show.

So here I am in flat number four, and given that there are no perfect flats, this may be the best of all. This time it’s between High Street Kensington and Notting Hill Gate, in a row of white buildings from a previous century. It has the most important thing I need in a flat, which is a long table where I can work — because I’m not here to sightsee. I’m here to teach, and my weekends usually consist of commenting on proposals and first drafts, grading final drafts of essays . . . But as I sit here in the living room writing, I can look out the tall front window facing the street, and there is a tree, tall and leafy and green, keeping me company. There is also a bedroom facing the back, and through that smaller window I can see more trees, the ones in which the birds are chattering away — somewhere back there is Kensington Gardens. The flat also contains a bathroom and a narrow kitchen, too small for a regular refrigerator or stove. Instead, I have a sort of half-refrigerator, a cooktop with two convection burners that have convinced me never to get convection burners, and a microwave. I also have a combination washer and dryer that takes about three and a half hours to wash and dry a load of laundry, but it’s my very own washer and dryer, which is more than I have in Boston, where I’m dependent on the building laundry room. To me, it feels luxurious.

Each time I come to London to teach, I stay for at least six weeks, which means I’m really living here — I need to buy groceries, do laundry, commute to work. The experience makes me consider and sometimes reconsider what it takes to live somewhere, to make a home there. Of course this isn’t my home, really. But even for six weeks, I try to make it a home away from home. It has made me realize that for basic happiness, I need much less than I already have in Boston. For example, in Boston I have a closet full of clothes, and here I have only a suitcase worth–but that’s enough for six weeks of teaching and grading and going to museums.

What does it mean to feel at home? I suppose it means that you feel a sense of ease moving around a place. You know where to go for the things you need. For my basic groceries, I go to a small Sainsbury’s a few blocks away. That’s where I buy milk and orange juice and yogurt. For anything more elaborate, there’s the Marks & Spencer on Kensington High Street or a Waitrose near the university campus, where I can pick up groceries on my way home. Along the High Street are a Ryman’s for pens and paper and whiteout as well as a hardware store that also sells housewares of various sorts. Also close to me are a beautiful old church where one can quietly sit and contemplate (because this is England and the churches are open), as well as Kensington and Holland Parks to walk in. So food for the body and food for the soul are both within walking distance. I almost forgot to mention that there is a large Waterstones on the High Street — that’s a bookstore, so food for the mind is within walking distance as well.

And I suppose feeling at home also means that you have enough. It’s amazing how little is enough for six weeks. I planned carefully, so that every item of clothing I packed went with all the others — in shades of black and beige and burnt orange and olive green. I suppose it could be called a capsule wardrobe, but I prefer to think of it as a “suitcase wardrobe.” It was challenging to plan, because one never knows what one will get with London weather. So far we’ve had beautifully sunny days as well as cold, windy ones — and several days of serious rain. Of course I’ve bought a few things since I’ve been here, because one of my personal failings is buying clothes I fall in love with (“How pretty! I can imagine walking through a rose garden in that dress!”), even though I already have enough for all practical and impractical purposes. But I’ve been strict with myself — they need to match the items I already have. When I leave here, they will also need to fit into the suitcase.

But I want to dig a bit deeper into this idea of home — what makes this place feel homey? My basic needs are met, that’s certainly part of it. I can move easily around this space, both inside the apartment and outside in the city. But there is something else — something less tangible. This apartment is filled with light and air, and in the mornings with birdsong. There is a sense of peace. That’s it, I think — home is where you feel peaceful, where your spirit is light. Where you can find ordinary happiness in doing the laundry, cooking dinner, sitting down to finish grading a set of essays. Where there is a silence that is not complete silence, because you can hear the sounds of daily life around you — the sound of a neighbor moving around in the adjoining flat, the wind in the leaves of the tree outside the window, a distant car horn.

I know that I will often be in the middle of bustle and crowds — I will be in airports and tube stations. I will be in the middle of the political turmoil of our times (aren’t we all?). But finding a home, even away from home, is necessary for the soul. I think it’s what we all crave, in the end — that sense of peace and belonging. Of being at home, somewhere in this busy world.

(The image is my front window in Kensington.)

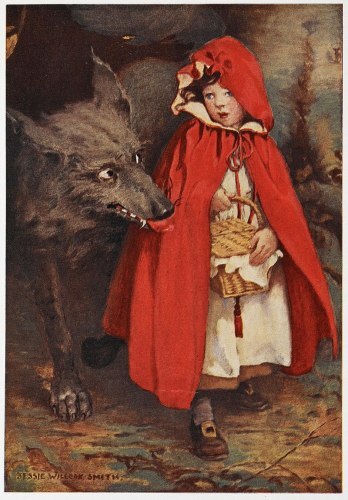

May 4, 2025

Imagining Fairytale Resistance

The title of this post comes from a book that will be published sometime this year: Women of the Fairy Tale Resistance by Jane Harrington. I have not read the book yet, but of course I will when it comes out. The book is subtitled The Forgotten Founding Mothers of the Fairy Tale and the Stories That They Spun, and it focuses on 17th century writers of fairy tales like Marie-Catherine d’Aulnoy.

Hopefully I can write about that book once I’ve read it. But what I want to focus on now is the term “fairytale resistance,” which struck me as soon as I heard it. What would a fairytale resistance look like nowadays, rather than in the seventeenth century?

Let’s start with a story. It’s the story of a young woman who walks through the forest to her grandmother’s house, carrying a basket with bread and wine. Along the way, she meets a man who asks her what she is doing. She tells him that she is going to her grandmother’s house at the edge of the village. She doesn’t know (you probably didn’t know) that the man is a werewolf (a bzou in antique French). As soon as she’s out of sight along the path, the man turns into his wolf form and runs through the forest to grandmother’s house. He eats grandmother up and, in man form again, dresses himself in her clothes.

You know, more or less, the story I’m taking about. But this is a slightly different version in which the young woman does not have a red cap — Charles Perrault added the cap later. This young woman gets to grandmother’s house, and when the werewolf dressed as grandma tells her to get into bed with him, she quickly realizes what’s going on. She says she needs to go out to relieve herself. The werewolf says, “All right, as long as you tie a rope to your ankle. I will hold the end of the rope. That way, I can tell if you try to run away.” She ties the rope to her ankle, but when she gets outside, she unties the rope and ties it around the trunk of a plum tree. By the time the werewolf figures out what’s happened, she has run away. He runs after her, and she can see him chasing behind, perhaps catching up. Is he in wolf or man form at this point? The story does not say, but he can run more quickly in wolf form. Either way, I suspect she is frightened of being caught. The girl comes to a river and asks the washerwomen to help her. They raise the sheets they are washing so she can run over them. When the werewolf arrives and tries to run over the sheets as well, they lower their sheets and he drowns.

This story was told, in slightly different forms, in late medieval France, and it’s the story that eventually became our “Little Red Riding Hood.” I’ve put details from slightly different versions together to create a narrative of my own — as a storyteller would have done at that time.

But this is what fairytale resistance looks like. When you realize that you’re unwittingly gotten in bed with werewolves (metaphorically, and I’m thinking about politics here), you need to get smart very quickly. And it’s very useful to find helpers and allies, like the laundresses in this story.

Fairytale resistance is what the peasantry spoke about, sang about. When you read the folk versions of fairy tales, they are filled with clever young women and men. In the folk version, Cinderella gets her dress from a hazel tree she has watered with her tears — a tree she planted on her mother’s grave. She is helped by birds, and when she goes to the ball (or church, in some versions), she is alone and clever. She gets no godmother to council her until, you guessed it, Perrault. He also came up with the impractical glass slippers. Vasilisa, whose Russian tale resembles Cinderella’s, survives the hut of Baba Yaga through her own cleverness and with the help of a doll given to her by her mother. She becomes Tsarina because she can weave linen so fine that the Tsar has never seen its like. The girl in “Frau Holle” is both clever and kind — she helps the laden apple tree and the oven filled with bread, and she serves Frau Holle so well that she is eventually rewarded.

Originally, fairytale resistance was a way for the peasantry to assert their power in a world that was often unfair and unkind. It meant telling stories about clever characters who defeated figures much stronger than themselves, like Jack and the giant, or Hansel and Gretel in the witch’s house. They did it through being smarter, smaller, quicker — and through helping others who would later help them — and usually through being kind. Even Jack, who is a sort of trickster, gave the gold to his mother. In the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, fairy tales would be taken up by tellers who were no longer peasants, but were generally not those in power either. Female tellers who might have been aristocrats, but had little control over their own lives in the France of Louis XIV. The poor (sometimes very poor) Jacob and Wilhelm Grimm. The governess Madame de Beaumont, whose husband had left her destitute. Hans Christian Andersen. The tales changed form, but they remained sites of resistance against those in power. They remained little rebellions in words, little formulas for how you revolt against the ruling classes.

So what were these formulas? Each tale is different, of course. But I think fairytale resistance looks something like this:

You have to be clever. Know what a werewolf looks like. Gather pebbles to scatter behind you, to lead you home again. Figure out how to trick the witch or giant who wants to eat you — being clever can also include being tricky. Even the “simple” third sons in fairy tales are usually smarter than their intellectual brothers.You have to be kind, because we live in a community of washerwomen and apples trees and bread ovens and birds that live in a hazel tree and possible pre-Christian goddesses, and we all need to help each other. Fairy tale heroes and heroines seldom accomplish things completely on their own. They have helpers and allies.You have to be skillful. Fairytale heroes and heroines know how to do things. Spinning the finest linen, sewing shirts out of nettles, cleaning houses on chicken legs — your skills will come in handy, especially the lowly skills that people might not value. Snow White is not just the fairest in the land — she is also an excellent housekeeper.You have to be patient. One commonality among fairy tale heroes and heroines is that they had to wait and endure, whether at home or, as in “East of the Sun and West of the Moon,” through a long quest to find the husband you thought was a bear, but was really a prince in disguise, and has now been taken away to marry an ogress.These are all valuable attributes when you’re trying to resist a power structure intent on restricting or even crushing you. Cleverness, kindness, skillfulness, patience — possessing these attributes, but also valuing these attributes more than power and wealth. I think that’s what fairytale resistance looks like. We live in a society that worships power and wealth, but what fairy tales tell us again and again is that those things are illusory–they can be won or lost, and ultimately they are always lost. English fairy tales end with “happily ever after,” but most traditional tales end with a phrase like “and they are still celebrating, if they have not died yet.” In other words, what waits at the end of every fairy tale, acknowledged by the formula, is King Death, before whom wealth and power mean nothing. Ultimately, the important thing is how you lived.

What fairytale resistance also looks like is telling stories about these things, stories that say “Be clever, be kind, be skillful, be patient.” Resist the mighty, find your own destiny, find your community. Know how to tell a werewolf when you see one, even if it’s dressed as your grandmother — or a politician.

(The image is Little Red Riding Hood by Jessie Wilcox Smith.)

February 2, 2025

What Would Feminine Energy Look Like?

Recently, one of the billionaires who own the technical empires to which we are all subject — a situation I’ve heard referred to as technofeudalism, which would make him one of our techlords — argued that corporations need more “masculine energy.” It’s easy to mock that statement. The technology companies that increasingly control our information and lives are largely male, particularly in their upper echelons, and they are replete with bro culture. There’s a reason their workers are known as techbros.

But when he used the term “masculine energy,” I don’t think he meant biological men. I think he meant that ideas like diversity and work-life balance had “neutered” (his term) corporations. They had become too focused on making the workplace welcoming and comfortable, as opposed to emphasizing “aggression” (again, his term) and competition. It’s a simplistic argument, and predictably, I want to complicate it.

As he did, I want to separate the terms “masculine” and “feminine” from actual biological men and women, and think about them as cultural categories. What would a positive idea of “masculine energy” look like? I don’t think it would look like aggression and competition, unless that competition was with oneself, to achieve a kind of personal excellence. When I think of what “masculine energy” could be, at its best, I think of exploration, discovery, innovation. I think of sailors who wanted to see what was over the horizon, physicists who wanted to understand the fundamental properties of matter. I think of a painter like Van Gogh, who created a way of seeing that had never existed before. Ansel Adams, whose photographs showed us the American West. Political leaders who created new ways of organizing society. I think of strength in the face of adversity, of perseverance. Of intellectual curiosity. It is a kind of energy that looks outward and upward, that wants to get to the moon and then perhaps to Mars. That kind of energy is something both men and women can have. Joan of Arc had plenty of “masculine energy.” So did Georgia O’Keefe.

The dark side of “masculine energy” is aggression, which is unhealthy competition — competition that seeks to break down the other rather than lifting up the self. At its unhealthiest, it’s war.

So then what would “feminine energy” look like? I think it would be a looking inward. Rather than trying to get to Mars, it would take care of the Earth. It would be an energy of care, of conservation, maybe even of restoration. It would be the energy of gardeners, of architects who create cities that are focused on the well-being of their inhabitants rather than a series of attention-grabbing skyscrapers. Of teachers, doctors and nurses, librarians. When I think about where we see this kind of “feminine energy,” I think of Mary Cassatt, but also W.B. Yeats, who tried to preserve and support Irish culture. It’s a kind of energy that does not get much credit, because it doesn’t look as spectacular as the other kind — it’s not as showy to teach a class of kindergarteners as to climb Mount Everest, but it’s arguably both harder and more necessary.

The drawback to talking about “masculine” and “feminine” energy is that those categories are based on cultural stereotypes. In a way, it might be easier to use terms that are more neutral, such as “red” and “green” energy — terms that are not so culturally loaded. But they would also not be as meaningful. They would not convey as much to a reader within this particular culture. I’m using them because I want to argue several things.

First, that these categories don’t map onto biological men and women. Virginia Woolf, creating a new kind of literature, could be seen as an example of “masculine energy.” A father taking care of his children could exemplify “feminine energy,” but so could a soldier defending his country from invasion (like a mother bear defending her cubs). Second, that a healthy person will have both kinds, the looking-outward and the looking-inward, the innovation and the preservation. So will a healthy society. Indeed, the entire profession of psychoanalysis could be seen as based on the “feminine energy” of searching deep inside oneself for answers. Freud might be upset to learn that his work has loads of “feminine energy,” but it does — as opposed to the more “masculine energy” of Plato imagining his ideal platonic forms in some hypothetical cave outside the realm of actual, situated human experience.

Finally, and this is why I wrote this whole argument: that our society (by which I mean 21st century America in particular) already overvalues “masculine energy” and undervalues “feminine energy,” which is why kindergarten teachers and librarians and firefighters and all the other professions that focus on care are underpaid (other than certain doctors, but even then, primary care physicians are paid less than surgeons). Our society rewards the disrupters and innovators. It does not reward the preservers.

We need to spend as much thought and energy on saving the Earth as on going to Mars. We need to pay as much attention to public parks as to skyscrapers. We need to focus on fiber artists and basket weavers and ceramicists as much as Pablo Picasso.

We are in a political moment when disruption is being prized — just this week, parts of the government were shut down. These were parts of the government that take care of people: children, low-income families, veterans. The goal was to disrupt the government in the name of greater efficiency, but in this process the value of care is being forgotten or ignored. There is a reason our society started to care about diversity: it came out of a realization that the institutions controlling our lives (the government, universities, corporations) were fundamentally unfair — that entire groups of people had been marginalized and excluded. And the push for work-life balance came out of a realization that people could not have a life outside of their work, an identify apart from their job descriptions. Both were problems with how our communities function — they can’t function properly when some people are left out, or when everyone is so tired they’d rather watch Netflix than spend time with their families or run for the local school board. We need more “feminine energy” in our political life as well.

I realize my categories and analysis are overly simplistic, and of course you should feel free to complicate them further, but I hope my central point makes sense. We need to take care of our environment, create parks and libraries, pay teachers and nurses, consider diversity and inclusion in our institutions, and make sure parents have time in the evening to play with their kids. That’s the kind of energy we need, whatever we call it.

(The image is Young Mother Sewing by Mary Cassatt.)

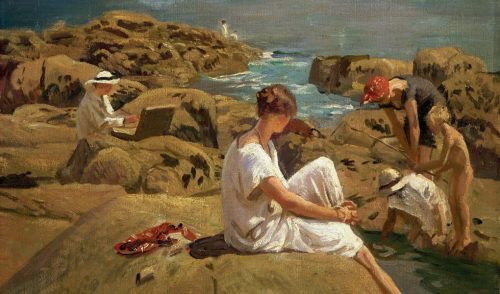

January 16, 2025

The Ocean and the Waves

When I was a child, we used to go to Ocean City, Maryland every summer. We used to drive in our old car, my brother and me in the back seat playing some game — usually “Infinite Questions,” which I had made up and which involved one person thinking of an object while the other asked as many questions as he or she wanted, in order to figure out what that object could be. Sometimes we sang “100 Bottles of Beer on the Wall.” There was no air conditioning, so we rolled the windows down, manually of course.

When we got to Ocean City, we always stayed at a small hotel — I would admire the big hotels where the wealthier people stayed, with their private beaches. But our small hotel was close to the public beach, so we would spend the day playing in the sand or swimming in the ocean, then go in the evening to have dinner at the crab shack, where they gave you a bunch of cooked crabs, a mallet, and some pieces of bread to go with the crab meat. The tables looked like picnic tables and were covered with brown paper, because you were doing to make a mess. Later, we might walk along the boardwalk. At the end of the boardwalk was a sort of fair, and one summer I remember there was a man who would guess various things about you, including your profession, and if he could not guess in three tries you would get a prize. My mother challenged him to guess her profession. He asked to look at her hands, then guessed that this short woman with two children and a Central European accent was a doctor on the second try.

It was a cheap summer vacation, and we went almost every summer — I think because my mother remembered her summers as a child at Lake Balaton, and she had a sense that getting children to water was simply what one did in the summer. We spent a lot of time in the ocean — that’s where I learned to swim among the waves.

All of this happened, but at the same time it’s part of a metaphor, because what I want to write about is the difference between the ocean and the waves.

When you swim in the ocean, you’re constantly bobbing up and down from the motion of the waves. But if you dive underneath, what you encounter is a sense of stillness — under the surface, the water does not appear to be moving. (Of course, there are such things as undertows, which are very dangerous. But most of the time, the water under the waves feels still.) Sometimes the waves are small, and they lap at you like a cat’s tongue. Sometimes they’re larger, and then they can be scary, especially when you’re a not-very-large girl treading water. It took me several summers to learn how to deal with those larger waves. What you do is, you dive under them. You dive into the stillness, and the wave passes over you. Then, you emerge on the other side.

Here comes the metaphor. We are all in the ocean, and there are so many waves! It may be an illusion that life seemed to be calmer when I was a child, back when telephones were securely anchored to the kitchen wall and could not follow you about everywhere you went. You could watch the news for an hour in the evening — you did not carry it around in your pocket. I don’t know, it certainly seems to me that we are swimming in a more turbulent ocean, and yet that turbulence may also be an illusion. All times are turbulent, after all. It’s just that we get so much information, more than we can really process. The waves come at us so quickly.

When I started teaching research techniques to my students, the difficult part was finding information. Now, the difficult part is sorting through all the information we have. That’s what we have to do in our daily lives as well — sort through it all and deal with it somehow. A quick look at social media immerses me in the waves: one friend has lost a parent, anther has a new pet, there are fires in Los Angles, new books coming out, the latest scandal or flavor of ice cream. The country is either collapsing or stronger than ever, depending on your point of view. We are inundated.

But if you put down your phone, unless you are in the middle of the turbulence — unless you are fleeing the fires — you return to the relative calm of ordinary life, where not a whole lot is happening at this particular moment. You return to still water. For example, I’m sitting here now, writing about the ocean and the waves, and after that I will need to make lunch, then work on a presentation for a faculty meeting, then continue planning for the semester. Outside it’s cold. The sky is white and there is snow on the ground, as there was last winter. The season moves on at its own pace, and in my own life, the waves do come, but they come much more slowly.

The point I want to make is, it’s so easy right now to feel as though we are swimming among the turbulence, where the waves are the information we receive from all over the world. At least some of the time, to keep from being overwhelmed — from getting salt water in our mouths and eyes — we need to dive down into the still water, let the waves move over us. We need to feel that the ocean is still there, supporting us.

It’s possible that a metaphor is not a good metaphor if it takes so long to explain. But what I want to say is that there are so many waves, but there is also still water underneath. I suggest you dive down into the still water. What is the still water? Well, the passing of seasons, for one. It’s winter now, and eventually spring will come, and that will happen over and over during our lifetimes. It’s a pattern we can hold on to. Another thing we can hold on to is good art. Fashions will come and go, and millionaires will buy fiberglass replicas of balloon dogs, but there will still be museums filled with beautiful paintings. You will still be able to go stand in front of a Monet. And good books will remain. There will be bestseller lists, and categories will have their day, but you will still be able to reach for Jane Austen or L.M. Montgomery. The best authors of my childhood — Ursula Le Guin, Patricia McKillip — are just becoming clear now. It takes a while to see what was truly worthwhile, what lasts.

In retrospect, it was a valuable lesson, learning to swim among the waves. But it’s only recently that I’ve appreciated its value as metaphor, as I’ve felt the turbulence of our times and tried to figure out how to live my own life without being overwhelmed by it. I just have to remember — if you dive down, there is always still water underneath.

(The image is On the Rocks by Laura Knight.)

December 30, 2024

Nothing is Wasted

Sometimes I get mad at myself for wasting time.

I have wasted time in the most ridiculous ways. I’ve watched YouTube videos on the history of ballet pointe shoes. I’ve watched Saturday Night Live skits about bridesmaids, and motivational speakers who talk about the need for a bedtime routine, and kittens being rescued in various ways. Don’t get me wrong, it’s a good and worthwhile thing to rescue kittens and have a bedtime routine. But there’s no need to watch videos about those things. I’ve read articles on decorating cottages in the Cotswolds and opinions pieces about the latest political shenanigans in Congress.

None of these things have helped me in obvious ways, so it’s easy to say they are a waste of time. Why do I watch or read them? I tried to think about why — boredom? Addiction to my phone? But the most obvious answer seemed to be curiosity. I saw a kitten in a drainpipe, and I wanted to know what happened to it. The ballerina showed me a pair of pointe shoes, and I wanted to know why. I saw a picture of the cottage, and wanted to know who had moved into it and why it had been painted that particular shade of green.

I am addicted to something, but it’s not my phone, or social media, or the news. What I’m addicted to is stories. With equal attention, I will watch a kitten rescue video or read an article in The Atlantic or start on a novel. And I will turn from one to another, or intersperse them — yes, I can watch an SLN skit on bridesmaid karaoke and then turn to a novel by Isabel Allende. One is serious literature, the other is — well, it’s sort of mental fast food, like french fries for the mind. And yet, I want to make an argument here about what it means to waste time as a writer.

What I want to argue is that . . . nothing is really a waste of time. In “The Art of Fiction,” Henry James wrote, “Try to be one of the people on whom nothing is lost.” These are the things that should not be lost on you when you’re, for example, watching a kitten rescue video:

What kind of kitten is it? Is it a black kitten with a white nose? How large is it? How large is the drainpipe? How did the kitten and drainpipe come to inhabit contiguous spaces?Who is rescuing it? What sort of voice do they have? What are they videotaping? Can you see their hands? Their feet? What techniques are they using to lure the kitten — the tried and true tuna method? Something else?What will the subsequent story of the kitten be? Will they adopt it? Foster it? Is it going to a shelter? If there is a happy ending to this story (and there almost invariably is), what is that happy ending?What storytelling techniques is the videographer using? What is the beginning, middle, and end? Are you in suspense? Is there music added? How are your emotions being affected and possibly even manipulated?Who are you, lying on the sofa watching the kitten rescue video? Are you doing it because you’re tired? Bored? Desperately in need of reassurance that this is a world in which kittens are rescued?All of those things are elements of story. All of them are things you can learn from as a writer, a storyteller. You can learn from them consciously, but even if you’re just lying on the sofa, vegging out (what kind of vegetable are you? a carrot? a cauliflower? and why?), your subconscious mind is learning learning learning, because if you’re a writer, it never stops learning.

Now, this is not to say that you should spend your entire life watching YouTube videos, or even reading The Atlantic. Or even reading Isabel Allende. At some point, you need to do what you were made for and actually write. But as you write — as you try to capture your ideas in prose or verse — everything you ever watched or listened to or read will come to help you. It will form the mental material for you to work with. A joke you heard a comic tell on a Netflix special will suggest a way a character can say something, a turn of phrase. You will describe the utter mess a character makes of a bedtime routine, and that mess (“Lydia could not fall asleep. Had she meditated the wrong way? There was a right way and a wrong way, and surely she had done it the wrong way. She should get up and watch that YouTube video again. The woman with the soothing voice, who had tortoiseshell-framed glasses and some sort of PhD although it was not entirely clear what her doctorate was actually in, would tell her. And then she would mediate the right way, and be able to fall asleep. She checked her phone. It was 3:10 am.) becomes characterization.

I would expand this to more than YouTube videos or podcasts or magazine articles. Try to be one of those people on whom nothing, not the colors of the fall leaves, not the way to darn a sweater with a hole in it, not the various ways in which people speak when they are just starting to learn English, is lost. Watch and listen and learn. Notice and notice and notice. Be infinitely curious. Have a hundred tabs open in your brain.

Recently, for the novel I’m currently working on, I had to research Pop-Tarts. Did you know that there are now chocolate chip pancake Pop-Tarts? What strange, uncanny things they are, those toaster pastries: neither quite breakfast nor dessert. When does one eat them? As far as I can tell, they are almost always eaten as snacks. There is, in fact, no proper time to eat Pop-Tarts except in between meals, surreptitiously, hiding the crumbs afterward. In my novel, there is a fairy creature with an inordinate fondness for them. They seem like the sort of thing fairy creatures would like.

One nice thing about being a writer is that nothing is ever really wasted. As long as, afterward, you write about it . . .

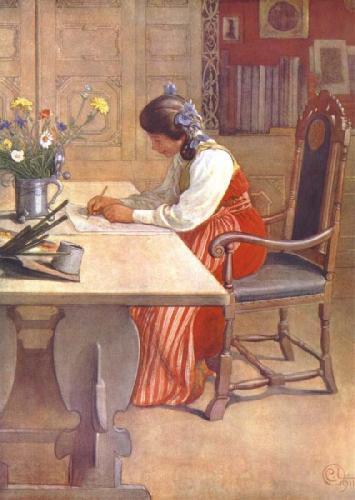

(The image is Hilda by Carl Larsson.)