Matt Rees's Blog - Posts Tagged "global"

The New (Foreign) Journalism

The New York Times features me in an article published this weekend about Global Post, the new foreign news website. As the Times explains, Global Post is intended to replace all the foreign news that's no longer produced by US newspapers, magazines and tv channels -- because those media "cut costs" and fired everyone. I've been writing for Global Post, which is run by a chum of mine who worked in the Middle East for The Boston Globe, and enjoying the freedom from starchy journalistic constraints it gives me. Here's what I wrote about my jaunt in Hillary Clinton's Ramallah motorcade earlier this month. Read it. Definitely not starchy.

Global Post: Bibi in a corner

Obama presses Israeli Prime Minister Netanyahu to stop building in West Bank settlements. By Matt Beynon Rees - GlobalPost May 26, 2009

JERUSALEM — One morning late last week, Israeli Border Police showed up at Maoz Esther, an outpost of Israeli settlers in the West Bank near Ramallah. They waited for a Bible study class to finish, tore down the settlers’ five little shacks and ran the residents off.

A few hours later, the settlers returned, nailing together the battered pieces of drywall shunted aside by the government. Maoz Esther rose again.

This kind of half-hearted approach to clearing out illegal outposts is the way Israel has always handled the settlers. Read more...

JERUSALEM — One morning late last week, Israeli Border Police showed up at Maoz Esther, an outpost of Israeli settlers in the West Bank near Ramallah. They waited for a Bible study class to finish, tore down the settlers’ five little shacks and ran the residents off.

A few hours later, the settlers returned, nailing together the battered pieces of drywall shunted aside by the government. Maoz Esther rose again.

This kind of half-hearted approach to clearing out illegal outposts is the way Israel has always handled the settlers. Read more...

Netanyahu holds his line

Israeli Prime Minister ignores Obama and reiterates same policies

by Matt Beynon Rees on Global Post

JERUSALEM — It’s as if Obama never happened.

Less than two weeks ago President Barack Obama laid out his plans for the Middle East in a speech in Cairo. He called for a freeze on Israeli settlement construction, among other things.

Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu immediately announced that he’d make a key policy address in Tel Aviv. Commentators wracked their brains figuring out how Bibi, the nickname by which the Likud leader is known, would walk the tightrope between his nationalist coalition — which is very supportive of the West Bank settlements and disdains the idea of a Palestinian state — and Obama, who had made it clear that he sees the settlements as Israel’s main contribution to the failure of peace efforts.

But Netanyahu outsmarted them all. No smokescreen, no artful diplospeak, no talking out of both sides of his mouth.

Nothing but old-school Bibi.

The big policy speech turned out to be filled with typical nationalist rhetoric about the settlements. The olive branch held out to the Palestinians was loaded with the kind of conditions Netanyahu surely knows are unacceptable in Ramallah — let alone Gaza.

“We would be prepared to reach agreement as to a demilitarized Palestinian state side by side with the Jewish state,” Netanyahu told his audience at the Begin-Sadat Center for Strategic Studies at Bar-Ilan University in Tel Aviv.

He said “Palestinian state,” but he added an adjective that grates rather hard on the Palestinian ear: “demilitarized.” For Netanyahu that’s important because a militarized Palestinian state would, as he sees it, be much as Gaza is today, with the capacity to rain missiles on Tel Aviv and the country’s international airport. It could make a military alliance with Iran, like Hezbollah on Israel’s northern border and Hamas in Gaza. We’ve all seen how that turned out for Israel.

To Palestinians, a demilitarized state sounds like no state at all. Chief Palestinian negotiator Saeb Erekat said Netanyahu would “wait a thousand years to meet a Palestinian who’d accept his conditions.”

As for Obama’s gripe about settlements, Netanyahu seemed at first to be edging toward a compromise, something so cunning in its apparent straightforwardness that no one would notice he’d refused to comply with the American demands. “We have no intention of founding new settlements,” he said.

Well, that’s not the heart of Obama’s argument. He doesn’t want to be deflected by Israel pulling out of a few remote hilltop outposts. The U.S. wants even existing settlements to stay as they are — not growing by so much as a single brick — until the future of the land on which they stand is decided.

But Netanyahu trotted out the same formula Israel has always used for evading a settlement freeze: so-called natural growth. “We must give mothers and fathers the chance of bringing up their children as is the case anywhere in the world,” he said.

In other words, if children grow up in a settlement, Israel is bound to build a home for them there when they want to have their own place, so they don’t have to move elsewhere to find accommodation.

As if their parents didn’t move to the settlements from somewhere else.

As if Barack Obama didn’t insist there be no “natural growth” in the settlements.

No one expects Netanyahu to go head to head with Obama. The speech wasn’t intended as a gauntlet in the face of the U.S. But the Israeli prime minister is sailing pretty close to the White House wind.

It all played well with Netanyahu’s right-wing Likud Party. “It was a Zionist speech from his faith and heart,” said Limor Livnat, a leading Likud hawk. “I’d have preferred he hadn’t said ‘Palestinian state,’ but it was a good speech.”

The country’s rather lackluster opposition recognized that Netanyahu hadn’t given ground to Obama. “The speech was typical Netanyahu,” said Ofer Pines, a legislator from the Labor Party (Labor is part of the coalition, but some of its lawmakers including Pines refused to join the government.) “He said a very small ‘Yes,’ and a very big ‘No.’ He’s really only talking to himself.”

Except he’s not the only one listening. There must surely have been bemusement in Washington, as officials watched the speech, waiting for Netanyahu to adjust his previous positions.

Wait on. The Palestinians must recognize Israel as a Jewish state, he said. Jerusalem, too, “would be the united capital of Israel.” He didn’t even offer to open the checkpoints into Gaza to let in construction material to rebuild the city ruined in the war between Israel and Hamas at the turn of the year.

The most optimistic of assessments — at least among those who oppose Netanyahu — was that the speech was just words. “It’s not what he says, it’s what he does after this that interests me,” said Haim Ramon, a legislator from the opposition Kadima Party.

Obama will surely second that.

by Matt Beynon Rees on Global Post

JERUSALEM — It’s as if Obama never happened.

Less than two weeks ago President Barack Obama laid out his plans for the Middle East in a speech in Cairo. He called for a freeze on Israeli settlement construction, among other things.

Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu immediately announced that he’d make a key policy address in Tel Aviv. Commentators wracked their brains figuring out how Bibi, the nickname by which the Likud leader is known, would walk the tightrope between his nationalist coalition — which is very supportive of the West Bank settlements and disdains the idea of a Palestinian state — and Obama, who had made it clear that he sees the settlements as Israel’s main contribution to the failure of peace efforts.

But Netanyahu outsmarted them all. No smokescreen, no artful diplospeak, no talking out of both sides of his mouth.

Nothing but old-school Bibi.

The big policy speech turned out to be filled with typical nationalist rhetoric about the settlements. The olive branch held out to the Palestinians was loaded with the kind of conditions Netanyahu surely knows are unacceptable in Ramallah — let alone Gaza.

“We would be prepared to reach agreement as to a demilitarized Palestinian state side by side with the Jewish state,” Netanyahu told his audience at the Begin-Sadat Center for Strategic Studies at Bar-Ilan University in Tel Aviv.

He said “Palestinian state,” but he added an adjective that grates rather hard on the Palestinian ear: “demilitarized.” For Netanyahu that’s important because a militarized Palestinian state would, as he sees it, be much as Gaza is today, with the capacity to rain missiles on Tel Aviv and the country’s international airport. It could make a military alliance with Iran, like Hezbollah on Israel’s northern border and Hamas in Gaza. We’ve all seen how that turned out for Israel.

To Palestinians, a demilitarized state sounds like no state at all. Chief Palestinian negotiator Saeb Erekat said Netanyahu would “wait a thousand years to meet a Palestinian who’d accept his conditions.”

As for Obama’s gripe about settlements, Netanyahu seemed at first to be edging toward a compromise, something so cunning in its apparent straightforwardness that no one would notice he’d refused to comply with the American demands. “We have no intention of founding new settlements,” he said.

Well, that’s not the heart of Obama’s argument. He doesn’t want to be deflected by Israel pulling out of a few remote hilltop outposts. The U.S. wants even existing settlements to stay as they are — not growing by so much as a single brick — until the future of the land on which they stand is decided.

But Netanyahu trotted out the same formula Israel has always used for evading a settlement freeze: so-called natural growth. “We must give mothers and fathers the chance of bringing up their children as is the case anywhere in the world,” he said.

In other words, if children grow up in a settlement, Israel is bound to build a home for them there when they want to have their own place, so they don’t have to move elsewhere to find accommodation.

As if their parents didn’t move to the settlements from somewhere else.

As if Barack Obama didn’t insist there be no “natural growth” in the settlements.

No one expects Netanyahu to go head to head with Obama. The speech wasn’t intended as a gauntlet in the face of the U.S. But the Israeli prime minister is sailing pretty close to the White House wind.

It all played well with Netanyahu’s right-wing Likud Party. “It was a Zionist speech from his faith and heart,” said Limor Livnat, a leading Likud hawk. “I’d have preferred he hadn’t said ‘Palestinian state,’ but it was a good speech.”

The country’s rather lackluster opposition recognized that Netanyahu hadn’t given ground to Obama. “The speech was typical Netanyahu,” said Ofer Pines, a legislator from the Labor Party (Labor is part of the coalition, but some of its lawmakers including Pines refused to join the government.) “He said a very small ‘Yes,’ and a very big ‘No.’ He’s really only talking to himself.”

Except he’s not the only one listening. There must surely have been bemusement in Washington, as officials watched the speech, waiting for Netanyahu to adjust his previous positions.

Wait on. The Palestinians must recognize Israel as a Jewish state, he said. Jerusalem, too, “would be the united capital of Israel.” He didn’t even offer to open the checkpoints into Gaza to let in construction material to rebuild the city ruined in the war between Israel and Hamas at the turn of the year.

The most optimistic of assessments — at least among those who oppose Netanyahu — was that the speech was just words. “It’s not what he says, it’s what he does after this that interests me,” said Haim Ramon, a legislator from the opposition Kadima Party.

Obama will surely second that.

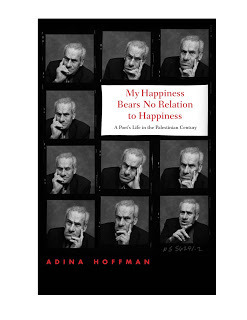

When poets do the talking

A new book examines the lives of Palestinian poets

By Matt Beynon Rees - on GlobalPost

JERUSALEM — Whenever Palestinian and Israeli artists get together for public “dialogues,” it always seems to end with the Israelis saying, “We’re sorry,” and the Palestinians responding, “Screw you anyway.”

That was how it went at a literary conference in the Jerusalem monastery at Tantur where I moderated a couple such discussions two years ago.

Except for the opening session.

The day began with a reading by Taha Muhammad Ali, a poet who lives in Nazareth, and his translator Peter Cole, a native of New Jersey and now a Jerusalem resident. Taha, who was then 75 years old, recited several of his poems, which Cole read in English.

Taha was avuncular and bumbling, endearing him to the audience of international publishers. But his poetry was deceptively incisive and personal, transcending the sense of victimization that would color the panel discussions for the rest of the day. Somehow he seemed to be the only one that day who had anything real to say.

"Don’t aim your rifles / at my happiness, / which isn’t worth / the price of a bullet,” Taha read. “My happiness bears / no relation to happiness.”

The warmth and intelligence of Taha’s readings drove Adina Hoffman, a Jerusalem-based writer and wife of translator Cole, to plan a biography of the poet (“My Happiness Bears No Relation to Happiness: A Poet’s Life in the Palestinian Century,” Yale University Press). Only then did she discover that, despite all the ink spilled on the Palestinian issue over the years, no one had ever written a biography of any Palestinian poet.

So she expanded the book. Using Taha as the central figure, she constructed the intersecting life stories of writers as diverse as Mahmoud Darwish, the "national" poet whose death last year prompted weepy editorials around the world, and Rashid Hussein, the most original and tortured of them, who died alone and drunk in New York 30 years ago.

Hoffman’s book is a way for readers to get around the usual stereotypes of the Palestinians as they’re portrayed in the cliches of their political struggle. She looks at the fascinating day-to-day, emotional history of this troubled people as told through their dynamic poetic culture.

“One can get a different idea of Palestinians as people through the history of their poets,” Hoffman told GlobalPost. “Poetry and poets occupy such an essential role in Palestinian society: Throughout much of the last century, poetry has served as one of the most important means of political and social expression for the Palestinian people — and the poets who’ve given voice to that impulse are central to the culture.”

Their poetry forms a gap in our knowledge of the Palestinians because of the way reporters cover their story — focusing on the violence and pyrotechnics and screaming, rather than on what people actually feel beneath it all.

“So much of the news coverage of the Palestinian story winds up treating them as a faceless group — whether a group of terrorists or a group of downtrodden victims,” Hoffman said. “I wanted to offer a view of Palestinian life that depicted as precisely and deeply as possible the full human range of feeling and complexity that exist in that culture.”

Hoffman uses Taha’s story as the framework for an alternative telling of Palestinian history, eschewing the slogans of political leaders and focusing on the soul-searching of young poets and writers.

You might think that would draw you away from reality into the realms of fantasy. But, as I’ve discovered in writing a series of Palestinian crime novels based on real stories I’ve reported, it’s only when a writer examines the underlying emotions of his subject that he uncovers the truth.

“The truest poetry is the most feigning,” Shakespeare wrote. Journalists, from whom we’re accustomed to getting our information about the Palestinians, aren’t supposed to be “feigning” at all. The result: no poetry and, often, no truth.

Hoffman’s telling of Taha’s story is particularly important because his life encompasses almost every element of the Palestinian experience. Born in 1931 in the village of Saffuriya, his family was expelled during the 1948 war which founded Israel. They fled to Lebanon, snuck back to Nazareth, and became refugees within Israel. He saw the devastation of war, too, on a visit to Lebanon in search of his childhood sweetheart.

Taha supported his family by running a souvenir shop for tourists visiting the town where Jesus grew up. He slowly developed a literary style that was at odds with traditional, highly formulaic Arab verse. Neither did he follow the incantatory public style of Darwish and the best known Palestinian poets.

Hoffman observes that Taha’s largely free verse (which many Palestinians rejected as simple prose chopped up into lines) is based around a classical Arabic concept of “a difficult, elusive, or even inscrutable simplicity.”

That simplicity is embodied in the poet’s peasant background, which Hoffman tells in vivid detail. Much of the book’s early chapters are devoted to life in Saffuriya, before the village was replaced with an Israeli community.

But it isn’t yet another regurgitating of Palestinian suffering. Her portrait of the village illustrates the richness of life there, showing how the memory of Saffuriya was part of “the world that surrounded these poets and that inspired them to write,” as she said.

It’s the remembrance of that world that dominates Taha’s poetry even six decades after Saffuriya ceased to exist. Hoffman’s account preserves the memory by recounting it and by introducing readers to the poetry that grew out of it.

Israelis riot, thanks be to God

Orthodox Jews face off against secularists in the Holy Land — a sign that all is well. By Matt Beynon Rees - GlobalPost

JERUSALEM — Ultra-orthodox Jews have been rioting the last few weeks against a parking lot the municipality wants to leave open during the Jewish Sabbath, leading to dozens of arrests and quite a few moderate to serious injuries. Secular activists have held protests in favor of free garaging for those who defy God by driving on Saturday.

All of which is a sign of good times in Israel.

Here’s why: It shows that Israelis think there’s nothing worse to worry about.

When I first came to Jerusalem in 1996, the ultra-Orthodox, or "Haredim" as they’re known here (it means “those who quake,” as in quaking before the wrathful God of the Jewish Bible) used to riot over a major thoroughfare that ran through one of their neighborhoods. They wanted Bar-Ilan Street closed between sundown Friday and the onset of Saturday night.

The Sabbath, they argued, ought to be sacred to every Jew, but at the very least no one ought to drive along Bar-Ilan, reminding them that its sanctity was being violated (by people who in turning their keys in the ignition were violating the rabbinic commandment not to kindle a flame on the Sabbath. It’s one of 39 tasks “set aside” on the Sabbath, because they were used in building the Ark of Covenant and therefore shouldn’t be carried out on the day of rest. No ritual slaughtering, tanning — of leather, that is — or separating of threads is allowed either, for example).

In my neighborhood, there was one old white-bearded rabbi who used to sit on a stool at the side of the road reading and wagging his finger at me as I drove by. But in more religious neighborhoods there was real violence. In Mea Shearim, the heart of ultra-Orthodox Jerusalem, gangs of black-hatted rioters used to light trash cans on fire, throw stones, kick and spit on journalists, and aim rather feeble punches at policemen. (Feeble because almost all the rioters are full-time yeshiva students who are, to say the least, short on regular physical activity.)

Secular activists used to counter-protest in Jerusalem. They’d turn up, too, at shopping malls near largely secular Tel Aviv to barrack the so-called “Sabbath inspectors,” non-Jews employed by the government to hand out fines to businesses that opened on the holy day.

This was among the most important issues of those days.

Then came the intifada. The Sabbath wasn’t so contentious anymore with suicide bombers working every day of the week. Maybe it’s also that Israeli Jews decided it was time to unite against their attackers.But a month ago, Jerusalem Mayor Nir Barkat (who replaced his ultra-Orthodox predecessor this spring) decided to leave a parking lot beside city hall open through the Sabbath. There are plenty of restaurants and bars open Friday night on a nearby street and Barkat’s aim was to prevent that street from filling with poorly parked cars.

Trouble was the lot wasn’t far from the edge of Beit Israel, one of the ultra-Orthodox neighborhoods stretching through central Jerusalem. Rabbis ordered out their spindly troops and rioting ensued.

Barkat switched the parking lot to one underneath the Old City walls beside the Jaffa Gate. If he’d started out there, things might’ve been different. But the rabbis had a good head of steam up and had returned to the rhetoric of my early days in Jerusalem — namely that secular Israelis were the worst anti-Semites, because they were self-hating and felt inadequate in the face of the dedication to religion of their ultra-Orthodox compatriots whose observance they wished to destroy.

So this past weekend the rioting reached a new stage of ugliness. Police arrested 57 ultra-Orthodox protesters, many of whom had bussed in for the Sabbath. One man fell off a wall and was in serious condition in hospital. The riots continued throughout Sunday, as the ultra-Orthodox protested for the release of those who had been arrested the previous day. The riots centered around Sabbath Square in the middle of Mea Shearim.

There are plenty of problems for Israel these days, not least the tortuous attempt by the current right-wing government to persist with settlement building in the face of (for the first time in years) genuine American insistence on a construction freeze. It isn’t beyond the bounds of possibility, too, that Europe might get tough on Israel unless peace talks with the Palestinians show some fruit.

But in comparison to the intifada, these are easy times for Israel. Long may the Sabbath be a time for rioting.

JERUSALEM — Ultra-orthodox Jews have been rioting the last few weeks against a parking lot the municipality wants to leave open during the Jewish Sabbath, leading to dozens of arrests and quite a few moderate to serious injuries. Secular activists have held protests in favor of free garaging for those who defy God by driving on Saturday.

All of which is a sign of good times in Israel.

Here’s why: It shows that Israelis think there’s nothing worse to worry about.

When I first came to Jerusalem in 1996, the ultra-Orthodox, or "Haredim" as they’re known here (it means “those who quake,” as in quaking before the wrathful God of the Jewish Bible) used to riot over a major thoroughfare that ran through one of their neighborhoods. They wanted Bar-Ilan Street closed between sundown Friday and the onset of Saturday night.

The Sabbath, they argued, ought to be sacred to every Jew, but at the very least no one ought to drive along Bar-Ilan, reminding them that its sanctity was being violated (by people who in turning their keys in the ignition were violating the rabbinic commandment not to kindle a flame on the Sabbath. It’s one of 39 tasks “set aside” on the Sabbath, because they were used in building the Ark of Covenant and therefore shouldn’t be carried out on the day of rest. No ritual slaughtering, tanning — of leather, that is — or separating of threads is allowed either, for example).

In my neighborhood, there was one old white-bearded rabbi who used to sit on a stool at the side of the road reading and wagging his finger at me as I drove by. But in more religious neighborhoods there was real violence. In Mea Shearim, the heart of ultra-Orthodox Jerusalem, gangs of black-hatted rioters used to light trash cans on fire, throw stones, kick and spit on journalists, and aim rather feeble punches at policemen. (Feeble because almost all the rioters are full-time yeshiva students who are, to say the least, short on regular physical activity.)

Secular activists used to counter-protest in Jerusalem. They’d turn up, too, at shopping malls near largely secular Tel Aviv to barrack the so-called “Sabbath inspectors,” non-Jews employed by the government to hand out fines to businesses that opened on the holy day.

This was among the most important issues of those days.

Then came the intifada. The Sabbath wasn’t so contentious anymore with suicide bombers working every day of the week. Maybe it’s also that Israeli Jews decided it was time to unite against their attackers.But a month ago, Jerusalem Mayor Nir Barkat (who replaced his ultra-Orthodox predecessor this spring) decided to leave a parking lot beside city hall open through the Sabbath. There are plenty of restaurants and bars open Friday night on a nearby street and Barkat’s aim was to prevent that street from filling with poorly parked cars.

Trouble was the lot wasn’t far from the edge of Beit Israel, one of the ultra-Orthodox neighborhoods stretching through central Jerusalem. Rabbis ordered out their spindly troops and rioting ensued.

Barkat switched the parking lot to one underneath the Old City walls beside the Jaffa Gate. If he’d started out there, things might’ve been different. But the rabbis had a good head of steam up and had returned to the rhetoric of my early days in Jerusalem — namely that secular Israelis were the worst anti-Semites, because they were self-hating and felt inadequate in the face of the dedication to religion of their ultra-Orthodox compatriots whose observance they wished to destroy.

So this past weekend the rioting reached a new stage of ugliness. Police arrested 57 ultra-Orthodox protesters, many of whom had bussed in for the Sabbath. One man fell off a wall and was in serious condition in hospital. The riots continued throughout Sunday, as the ultra-Orthodox protested for the release of those who had been arrested the previous day. The riots centered around Sabbath Square in the middle of Mea Shearim.

There are plenty of problems for Israel these days, not least the tortuous attempt by the current right-wing government to persist with settlement building in the face of (for the first time in years) genuine American insistence on a construction freeze. It isn’t beyond the bounds of possibility, too, that Europe might get tough on Israel unless peace talks with the Palestinians show some fruit.

But in comparison to the intifada, these are easy times for Israel. Long may the Sabbath be a time for rioting.

Rabbis: No pie for Jesus!

Her methods may be kosher, but in Israel baker Pnina Konforti faces a bigger commercial obstacle: She's a Messianic Jew.

By Matt Beynon Rees - GlobalPost

GAN YAVNEH, Israel — I always thought that by following kosher laws religious Jews only missed out on certain flavors and debatable delicacies. Turns out that by turning their back on “treyf” they also steer clear of Jesus.

At least that’s the verdict of rabbinates in two Israeli towns who’ve been denying a kosher certificate to a local cafe owner for three years — not because she doesn’t conform to the laws of “kashrut,” but because she’s a “Messianic Jew.”

Pnina Konforti, owner of the two branches of Pnina Pie in Gan Yavneh and Ashdod, this month won a decision in Israel’s Supreme Court forcing the rabbinates of the towns to give her a kosher certificate. Just because she believes in Jesus, the judges said, doesn’t mean she can’t keep kosher. Without the kosher certificate, many religious and traditional Jews refused to frequent the cafes and Konforti’s business was failing.

The case looks set to provoke a battle between the more secular organs of the government and the state rabbinate. It’s also a new point of conflict in the long battle between Israel — particularly its ultra-Orthodox community — and the Christian faith.

The rabbis insist they’re the ones who ought to decide about matters of kashrut and they refuse to allow a Messianic Jew (or a “Jew for Jesus” as they tend to be known in the U.S.) to receive a certificate. Though that sounds extreme, the rabbis aren’t entirely wrong (at least in the archaic terms of kosher law). After all, in Israeli wineries, non-Jews are forbidden from touching certain apparatus for fear of making the wine non-kosher — a prohibition going back to the days when a non-Jew might have used wine for idol worship.

Konforti’s point — which the Supreme Court accepted — is that she isn’t a non-Jew. She just happens to have decided during a stay in Ohio that the world’s most famous Jew, Jesus — or as she, an Israeli, calls him, “Yeshu” — is her savior.

The fear of Christian proselytizers or, even worse, Jews for Jesus is a common one among Israelis in general, and it has a long history that reaches back to a Europe where Jews were often persecuted or forced to convert to Christianity.

In that sense the court decision marks a rare gesture of conciliation by the organs of the Israeli state toward those who profess to be Christians.

It hasn’t always been that way.

In 1962, the Israeli Supreme Court denied citizenship to a Polish priest who had been born a Jew and converted to Christianity while hiding in a monastery to escape the Holocaust. Oswald Rufeisen, known as Brother Daniel, qualified for immigration under Israel’s “Law of Return” because he was born a Jew, but the court refused to accept a man who no longer called himself a Jew. (Eventually Rufeisen gained residence and died in a Haifa monastery a decade ago.)

Neither is pettiness a bar to paranoia. In my largely secular neighborhood of Jerusalem a few years ago, a tiny kiosk serving coffee in a small park was driven out of business because locals whispered that the owner was a Messianic Jew.

The lesson of such cases is that two thousand years of persecution at the hands of the church isn’t quickly forgotten, even by those who’ve never faced so much as a single anti-Semitic slur.

It’s a lesson only some in the Roman Catholic Church seem to have learned. Pope John Paul II won over many Israelis during his papacy with his visit to an Italian synagogue and talk of reconciliation during a 2000 visit to the Holy Land.

But the current pope, Benedict XVI, appeared cold and, to most Israelis, pro-Palestinian when he visited this spring. Many newspaper commentators complained that a former member of the Hitler Youth representing a faith with a history of persecuting Jews ought to have been less academic in his public addresses and more contrite toward Israel.

To understand the depth of fear among the ultra-Orthodox, consider the leaflets posted in Gan Yavneh warning residents against Konforti’s cafe: “Beware! Missionaries! What is hiding behind the Cafe-Bakery?” (In a community where television and radio are often not allowed, having been deemed negative modern influences, leaflets posted on walls are the favored way to pass information around among ultra-Orthodox Israelis.)

The answer, according to the leaflets: “Jews who sold their soul, betrayed their nation, and converted to Christianity.”

The leaflets advised citizens not to enter the cafe or “she will try to ensnare you in her Christian religion.”

Must be pretty good pie, you’re thinking.

I came across Pnina Pie in January when I visited Gan Yavneh during the war between Israel and Hamas in the Gaza Strip. Missiles from Gaza landed several times on this small town, which is home to an air force base and several thousand Tel Aviv commuters.

I concluded an interview with the town’s mayor by asking him where I could get a decent lunch. He directed me to Pnina Pie, where a young Russian immigrant served me excellent bourekas, flaky pastry triangles filled with potato and cheese.

Unaware of the lack of a kosher certificate at the establishment, I bought a strawberry pie and served it to some guests that night. It happens all four of these friends were observant Jews.

At least they were observant Jews. Maybe by now they believe in Jesus.

After all, it really was very good pie.

By Matt Beynon Rees - GlobalPost

GAN YAVNEH, Israel — I always thought that by following kosher laws religious Jews only missed out on certain flavors and debatable delicacies. Turns out that by turning their back on “treyf” they also steer clear of Jesus.

At least that’s the verdict of rabbinates in two Israeli towns who’ve been denying a kosher certificate to a local cafe owner for three years — not because she doesn’t conform to the laws of “kashrut,” but because she’s a “Messianic Jew.”

Pnina Konforti, owner of the two branches of Pnina Pie in Gan Yavneh and Ashdod, this month won a decision in Israel’s Supreme Court forcing the rabbinates of the towns to give her a kosher certificate. Just because she believes in Jesus, the judges said, doesn’t mean she can’t keep kosher. Without the kosher certificate, many religious and traditional Jews refused to frequent the cafes and Konforti’s business was failing.

The case looks set to provoke a battle between the more secular organs of the government and the state rabbinate. It’s also a new point of conflict in the long battle between Israel — particularly its ultra-Orthodox community — and the Christian faith.

The rabbis insist they’re the ones who ought to decide about matters of kashrut and they refuse to allow a Messianic Jew (or a “Jew for Jesus” as they tend to be known in the U.S.) to receive a certificate. Though that sounds extreme, the rabbis aren’t entirely wrong (at least in the archaic terms of kosher law). After all, in Israeli wineries, non-Jews are forbidden from touching certain apparatus for fear of making the wine non-kosher — a prohibition going back to the days when a non-Jew might have used wine for idol worship.

Konforti’s point — which the Supreme Court accepted — is that she isn’t a non-Jew. She just happens to have decided during a stay in Ohio that the world’s most famous Jew, Jesus — or as she, an Israeli, calls him, “Yeshu” — is her savior.

The fear of Christian proselytizers or, even worse, Jews for Jesus is a common one among Israelis in general, and it has a long history that reaches back to a Europe where Jews were often persecuted or forced to convert to Christianity.

In that sense the court decision marks a rare gesture of conciliation by the organs of the Israeli state toward those who profess to be Christians.

It hasn’t always been that way.

In 1962, the Israeli Supreme Court denied citizenship to a Polish priest who had been born a Jew and converted to Christianity while hiding in a monastery to escape the Holocaust. Oswald Rufeisen, known as Brother Daniel, qualified for immigration under Israel’s “Law of Return” because he was born a Jew, but the court refused to accept a man who no longer called himself a Jew. (Eventually Rufeisen gained residence and died in a Haifa monastery a decade ago.)

Neither is pettiness a bar to paranoia. In my largely secular neighborhood of Jerusalem a few years ago, a tiny kiosk serving coffee in a small park was driven out of business because locals whispered that the owner was a Messianic Jew.

The lesson of such cases is that two thousand years of persecution at the hands of the church isn’t quickly forgotten, even by those who’ve never faced so much as a single anti-Semitic slur.

It’s a lesson only some in the Roman Catholic Church seem to have learned. Pope John Paul II won over many Israelis during his papacy with his visit to an Italian synagogue and talk of reconciliation during a 2000 visit to the Holy Land.

But the current pope, Benedict XVI, appeared cold and, to most Israelis, pro-Palestinian when he visited this spring. Many newspaper commentators complained that a former member of the Hitler Youth representing a faith with a history of persecuting Jews ought to have been less academic in his public addresses and more contrite toward Israel.

To understand the depth of fear among the ultra-Orthodox, consider the leaflets posted in Gan Yavneh warning residents against Konforti’s cafe: “Beware! Missionaries! What is hiding behind the Cafe-Bakery?” (In a community where television and radio are often not allowed, having been deemed negative modern influences, leaflets posted on walls are the favored way to pass information around among ultra-Orthodox Israelis.)

The answer, according to the leaflets: “Jews who sold their soul, betrayed their nation, and converted to Christianity.”

The leaflets advised citizens not to enter the cafe or “she will try to ensnare you in her Christian religion.”

Must be pretty good pie, you’re thinking.

I came across Pnina Pie in January when I visited Gan Yavneh during the war between Israel and Hamas in the Gaza Strip. Missiles from Gaza landed several times on this small town, which is home to an air force base and several thousand Tel Aviv commuters.

I concluded an interview with the town’s mayor by asking him where I could get a decent lunch. He directed me to Pnina Pie, where a young Russian immigrant served me excellent bourekas, flaky pastry triangles filled with potato and cheese.

Unaware of the lack of a kosher certificate at the establishment, I bought a strawberry pie and served it to some guests that night. It happens all four of these friends were observant Jews.

At least they were observant Jews. Maybe by now they believe in Jesus.

After all, it really was very good pie.

As The (Palestinian) World Turns

Searching for a new script to get Hamas and Fatah to cooperate. By Matt Beynon Rees - GlobalPost

RAMALLAH, West Bank — Soap operas usually block out scenes with two cameras, one for each of the glaring opponents. The editor switches between each actor as they snarl and sneer. As for the plot, you can tune in every few months and nothing seems to have changed.

Sorry, did I write “soap operas?" I meant to type “current Palestinian politics.”

In the latest episode, Hamas — in the role of bad guy, at least according to most Western viewers of this particular soap — stares wild-eyed and affronted from the Gaza Strip toward Fatah in the West Bank. Fatah, playing the loose-living, stylish cousin, tosses its chin high and looks down its nose. Egyptian mediators pop in like script doctors searching for a new twist. But they come up with the same tired old plotlines.

Over a recent weekend, Egypt’s deputy chief of intelligence, General Muhammad Ibrahim, spent two days in Ramallah just trying to convince the different Palestinian factions that they ought to turn up in Cairo on July 25 for the next round in the “national reconciliation” talks — the seventh such meeting since the spring of 2007, when Hamas threw Fatah out of the Gaza Strip (and also threw some Fatah officials out of high windows).

Ibrahim’s suggestion, according to Palestinian officials, was for both sides to agree that Hamas would rule the Gaza Strip, while Fatah would control the West Bank.

Did I mention that he didn’t come with any new ideas?

The Egyptians hoped that if the two sides agreed not to be angry any more about the status quo, Fatah could be persuaded to contribute to rebuilding Gaza after the damage caused there by the war at the turn of the year. In return Hamas might consent to allow policemen from the Fatah-controlled Palestinian Authority to return to the Gaza Strip, the Egyptians suggested.

Ibrahim’s aim wasn’t to solve the entire problem of the Palestinian civil war, but rather to stanch the bleeding.

Without grabbing headlines, the blood is flowing. Hamas recently arrested a series of Fatah-affiliated Gazans who, according to human-rights organizations, face torture or injury during their incarceration. Fatah responded by rounding up more Hamas people in the West Bank.

Palestinian President Mahmoud Abbas sounded in no hurry to make a deal when he said Sunday that he’d "accept any Egyptian proposal that ends the internal rift and lifts the siege imposed on the Palestinian people." Except the proposals put to him over the weekend, of course, which he appears to have rejected.

Like any good soap opera, the reason for such hardheadedness is trouble inside the family.

Fatah officials face a party congress in early August and are reluctant to make any concessions to Hamas. Such a move could make them vulnerable to attack by party rivals striking a tough guy pose.

That’s likely to make the talks next week in Cairo a waste of time, though the Egyptians vowed to press ahead.

Hamas has been talking more softly about regional politics, even as it’s been taking a hard line against its compatriots. In late June, the group’s Damascus-based leader, Khaled Meshaal, said Hamas accepted the idea of a two-state solution for the Israeli-Palestinian conflict (even as he rejected Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu’s current demand that Palestinians recognize Israel as a Jewish state, calling it “racist, no different from Nazis.”)

Hamas seems to be in a bit more of a hurry than Fatah to make nice because of the desperate straits of Gaza’s population. Fatah refuses to budge in the Cairo talks unless it gets a true foothold in Gaza, where the Palestinian Authority pays the wages of civil servants and is largely ordering them to stay at home.

Even so, Hamas isn’t ready to roll over. It maintains the arrests of its activists in the West Bank were ordered by the Israeli army and the U.S. security coordinator to the region, Keith Dayton. (Israeli military officials say cooperation these days with the Palestinians is better even than during the years of the Oslo peace agreements — in the West Bank only, of course.)

Hamas also insists that the term of the current parliament be extended because, since it won a majority in the legislature in 2006, it has been unable to exert control due to international boycotts and, later, the civil strife with Fatah.

Perhaps Meshaal dropped his opposition to a two-state solution because he’s staring in the face of a three-state solution, in which Fatah gets an internationally recognized state in the West Bank and Hamas heads a pariah outpost in Gaza under the shadow of the Israeli war machine.

What would such states look like anyway? These days, despite the money flowing into the West Bank from the U.S. and the cash smuggled to Hamas by Iran, they’d be fairly sorry specimens.

The Palestinian Central Bureau of Statistics said this week that the population of the Palestinian territories was about 3.9 million, with 2.4 million people in the West Bank and 1.5 million in the Gaza Strip.

Of those, 25 percent are unemployed. With plenty of time for bad daytime TV.

RAMALLAH, West Bank — Soap operas usually block out scenes with two cameras, one for each of the glaring opponents. The editor switches between each actor as they snarl and sneer. As for the plot, you can tune in every few months and nothing seems to have changed.

Sorry, did I write “soap operas?" I meant to type “current Palestinian politics.”

In the latest episode, Hamas — in the role of bad guy, at least according to most Western viewers of this particular soap — stares wild-eyed and affronted from the Gaza Strip toward Fatah in the West Bank. Fatah, playing the loose-living, stylish cousin, tosses its chin high and looks down its nose. Egyptian mediators pop in like script doctors searching for a new twist. But they come up with the same tired old plotlines.

Over a recent weekend, Egypt’s deputy chief of intelligence, General Muhammad Ibrahim, spent two days in Ramallah just trying to convince the different Palestinian factions that they ought to turn up in Cairo on July 25 for the next round in the “national reconciliation” talks — the seventh such meeting since the spring of 2007, when Hamas threw Fatah out of the Gaza Strip (and also threw some Fatah officials out of high windows).

Ibrahim’s suggestion, according to Palestinian officials, was for both sides to agree that Hamas would rule the Gaza Strip, while Fatah would control the West Bank.

Did I mention that he didn’t come with any new ideas?

The Egyptians hoped that if the two sides agreed not to be angry any more about the status quo, Fatah could be persuaded to contribute to rebuilding Gaza after the damage caused there by the war at the turn of the year. In return Hamas might consent to allow policemen from the Fatah-controlled Palestinian Authority to return to the Gaza Strip, the Egyptians suggested.

Ibrahim’s aim wasn’t to solve the entire problem of the Palestinian civil war, but rather to stanch the bleeding.

Without grabbing headlines, the blood is flowing. Hamas recently arrested a series of Fatah-affiliated Gazans who, according to human-rights organizations, face torture or injury during their incarceration. Fatah responded by rounding up more Hamas people in the West Bank.

Palestinian President Mahmoud Abbas sounded in no hurry to make a deal when he said Sunday that he’d "accept any Egyptian proposal that ends the internal rift and lifts the siege imposed on the Palestinian people." Except the proposals put to him over the weekend, of course, which he appears to have rejected.

Like any good soap opera, the reason for such hardheadedness is trouble inside the family.

Fatah officials face a party congress in early August and are reluctant to make any concessions to Hamas. Such a move could make them vulnerable to attack by party rivals striking a tough guy pose.

That’s likely to make the talks next week in Cairo a waste of time, though the Egyptians vowed to press ahead.

Hamas has been talking more softly about regional politics, even as it’s been taking a hard line against its compatriots. In late June, the group’s Damascus-based leader, Khaled Meshaal, said Hamas accepted the idea of a two-state solution for the Israeli-Palestinian conflict (even as he rejected Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu’s current demand that Palestinians recognize Israel as a Jewish state, calling it “racist, no different from Nazis.”)

Hamas seems to be in a bit more of a hurry than Fatah to make nice because of the desperate straits of Gaza’s population. Fatah refuses to budge in the Cairo talks unless it gets a true foothold in Gaza, where the Palestinian Authority pays the wages of civil servants and is largely ordering them to stay at home.

Even so, Hamas isn’t ready to roll over. It maintains the arrests of its activists in the West Bank were ordered by the Israeli army and the U.S. security coordinator to the region, Keith Dayton. (Israeli military officials say cooperation these days with the Palestinians is better even than during the years of the Oslo peace agreements — in the West Bank only, of course.)

Hamas also insists that the term of the current parliament be extended because, since it won a majority in the legislature in 2006, it has been unable to exert control due to international boycotts and, later, the civil strife with Fatah.

Perhaps Meshaal dropped his opposition to a two-state solution because he’s staring in the face of a three-state solution, in which Fatah gets an internationally recognized state in the West Bank and Hamas heads a pariah outpost in Gaza under the shadow of the Israeli war machine.

What would such states look like anyway? These days, despite the money flowing into the West Bank from the U.S. and the cash smuggled to Hamas by Iran, they’d be fairly sorry specimens.

The Palestinian Central Bureau of Statistics said this week that the population of the Palestinian territories was about 3.9 million, with 2.4 million people in the West Bank and 1.5 million in the Gaza Strip.

Of those, 25 percent are unemployed. With plenty of time for bad daytime TV.

So what, and who, really killed Arafat?

Poison? By Matt Beynon Rees - GlobalPost

RAMALLAH, West Bank — Yasser Arafat’s body lies in the back of the presidential compound, beyond the parking lot, in a mausoleum of stone and glass. Two guards in ceremonial uniforms that seem out of place in the camouflaged guerrilla world of Palestinian militias watch over the angled stone marking the former leader’s grave.

The gravestone gives Arafat’s date of birth in Arabic characters as Aug. 4, 1929, though researchers long ago uncovered a Cairo birth certificate stating that he was born three weeks later. The tomb notes his death as occurring on Nov. 11, 2004, a full week after the date of news reports from his Paris hospital that he was either dead or brain-dead.

The dates aren’t all about Arafat’s grave that is in dispute. Palestinian politics has been torn apart in the last week after a senior Palestine Liberation Organization official announced that the symbol of his people’s struggle had been the victim of a poison plot. Farouk Kaddumi named the two main conspirators as then-Israeli Prime Minister Ariel Sharon and current Palestinian President Mahmoud Abbas.

Kaddumi, who was head of the PLO’s political bureau under Arafat and nominally responsible for foreign affairs, is engaged in a struggle for control of the Palestinian national movement with Abbas. A conference of their Fatah faction is called for next month where young reformers close to Abbas hope to sweep away corrupt, older leaders. But the conference is to be held in the West Bank and Kaddumi, who rejected the Oslo Peace Accords, has never returned from exile.

That’s probably why he chose to reveal the “findings” of his investigation into Arafat’s death last week in the Jordanian capital Amman, according to senior Palestinian officials in the West Bank. But it doesn’t defuse the firestorm of rage unleashed in Ramallah where Abbas has shut down Al Jazeera, the international cable station that aired an interview with Kaddumi.

Why is Abbas so mad about what could surely be have been dismissed as the ravings of an angry party rival of advancing years? (Well, actually Abbas tried that. His aides called Kaddumi, who was born in 1931, “a sick mind” and “demented.”) That didn’t fly because most Palestinians encountered on the streets of Ramallah on a recent weekend said Kaddumi’s accusation confirmed precisely what they believed happened to their old leader.

If there’s doubt about Arafat’s death, it’s largely because his successor Abbas has never released a report by Arafat’s French doctors on what killed “The Old Man,” as Palestinians call him.

There was no autopsy, yet reports emerge from time to time about what the French doctors suspected ended Arafat’s 35-year reign as head of the PLO.

In Israeli newspapers it has become accepted that Arafat died of AIDS and that Abbas covered it up because of the shame of that disease — an element I worked into the plot of my Palestinian crime novel “The Samaritan’s Secret.”

If there was no autopsy, the Israeli newspapers have written, it’s because the results would’ve been a shocking indictment of Arafat’s morals that would’ve dirtied the whole Palestinian struggle. But then Israelis always did like to demonize Arafat by suggesting he was a sexual pervert.

Now Kaddumi accuses Abbas of taking his supporter Muhammad Dahlan, a former head of Gaza’s secret police, to a meeting with Prime Minister Sharon where it was agreed that Arafat — as well as certain other Palestinian leaders who rejected peace with Israel — would be poisoned.

Kaddumi says he decided to publish the information only when Abbas ordered the party conference to be held in the West Bank town of Bethlehem on Aug. 4. He maintains that since Arafat’s death he’s the true head of Fatah and, therefore, he ought to decide where the conference takes place. (Palestinian officials in Bethlehem told GlobalPost recently that they doubt the conference will take place at all, because Fatah is so divided.)

Kaddumi isn’t the first to suggest Arafat was poisoned. In 2004, Arafat’s cabinet secretary Ahmad Abdel Rahman told the Arabic-language London newspaper Al Hayat that Arafat was poisoned “with gas” during a meeting at his headquarters a year before his death.

After shaking hands with a group of international and Israeli peace campaigners who had cycled to his besieged office, Arafat vomited. Later he told Abdel Rahman: “Could it be that they got to me? Is it possible that 10 doctors can't find out what I'm suffering from?”

At that time, one of Arafat’s doctors told me that the leader had developed an infection in his blood that ultimately affected his internal organs.

When I visited Ramallah in those last days of Arafat’s regime, I found that people who spent a lot of time with the leader were deeply concerned. Not about Arafat’s blood, but about his state of mind. He went a year without washing the scarf he used to tie around his neck like an Ascot, one of them said. Another said he rambled about the old days in Beirut, whenever an aide would try to get him to address the disastrous situation of the Palestinian towns, which were subject to constant raids by the Israeli army.

It always struck me that one of them might have decided to put an end to the PLO chairman’s long decline.

When Arafat took a final turn for the worse, his long-time doctor, Ashraf al-Kurdi, prepared to come to him from his home in Jordan. Top PLO officials called Kurdi and told him not to make the journey to Ramallah.

Instead, Abbas and a few other PLO chiefs went with Arafat. They stayed by his side until he was dead (and then another week, perhaps, until they actually decided to announce his death).

Then they spent $1.75 million on his mausoleum. When he unveiled the completed structure in November 2007, Abbas said: “We will continue on the path of the martyred President Yasser Arafat.”

What kind of martyrdom it was, perhaps only Abbas knows.

RAMALLAH, West Bank — Yasser Arafat’s body lies in the back of the presidential compound, beyond the parking lot, in a mausoleum of stone and glass. Two guards in ceremonial uniforms that seem out of place in the camouflaged guerrilla world of Palestinian militias watch over the angled stone marking the former leader’s grave.

The gravestone gives Arafat’s date of birth in Arabic characters as Aug. 4, 1929, though researchers long ago uncovered a Cairo birth certificate stating that he was born three weeks later. The tomb notes his death as occurring on Nov. 11, 2004, a full week after the date of news reports from his Paris hospital that he was either dead or brain-dead.

The dates aren’t all about Arafat’s grave that is in dispute. Palestinian politics has been torn apart in the last week after a senior Palestine Liberation Organization official announced that the symbol of his people’s struggle had been the victim of a poison plot. Farouk Kaddumi named the two main conspirators as then-Israeli Prime Minister Ariel Sharon and current Palestinian President Mahmoud Abbas.

Kaddumi, who was head of the PLO’s political bureau under Arafat and nominally responsible for foreign affairs, is engaged in a struggle for control of the Palestinian national movement with Abbas. A conference of their Fatah faction is called for next month where young reformers close to Abbas hope to sweep away corrupt, older leaders. But the conference is to be held in the West Bank and Kaddumi, who rejected the Oslo Peace Accords, has never returned from exile.

That’s probably why he chose to reveal the “findings” of his investigation into Arafat’s death last week in the Jordanian capital Amman, according to senior Palestinian officials in the West Bank. But it doesn’t defuse the firestorm of rage unleashed in Ramallah where Abbas has shut down Al Jazeera, the international cable station that aired an interview with Kaddumi.

Why is Abbas so mad about what could surely be have been dismissed as the ravings of an angry party rival of advancing years? (Well, actually Abbas tried that. His aides called Kaddumi, who was born in 1931, “a sick mind” and “demented.”) That didn’t fly because most Palestinians encountered on the streets of Ramallah on a recent weekend said Kaddumi’s accusation confirmed precisely what they believed happened to their old leader.

If there’s doubt about Arafat’s death, it’s largely because his successor Abbas has never released a report by Arafat’s French doctors on what killed “The Old Man,” as Palestinians call him.

There was no autopsy, yet reports emerge from time to time about what the French doctors suspected ended Arafat’s 35-year reign as head of the PLO.

In Israeli newspapers it has become accepted that Arafat died of AIDS and that Abbas covered it up because of the shame of that disease — an element I worked into the plot of my Palestinian crime novel “The Samaritan’s Secret.”

If there was no autopsy, the Israeli newspapers have written, it’s because the results would’ve been a shocking indictment of Arafat’s morals that would’ve dirtied the whole Palestinian struggle. But then Israelis always did like to demonize Arafat by suggesting he was a sexual pervert.

Now Kaddumi accuses Abbas of taking his supporter Muhammad Dahlan, a former head of Gaza’s secret police, to a meeting with Prime Minister Sharon where it was agreed that Arafat — as well as certain other Palestinian leaders who rejected peace with Israel — would be poisoned.

Kaddumi says he decided to publish the information only when Abbas ordered the party conference to be held in the West Bank town of Bethlehem on Aug. 4. He maintains that since Arafat’s death he’s the true head of Fatah and, therefore, he ought to decide where the conference takes place. (Palestinian officials in Bethlehem told GlobalPost recently that they doubt the conference will take place at all, because Fatah is so divided.)

Kaddumi isn’t the first to suggest Arafat was poisoned. In 2004, Arafat’s cabinet secretary Ahmad Abdel Rahman told the Arabic-language London newspaper Al Hayat that Arafat was poisoned “with gas” during a meeting at his headquarters a year before his death.

After shaking hands with a group of international and Israeli peace campaigners who had cycled to his besieged office, Arafat vomited. Later he told Abdel Rahman: “Could it be that they got to me? Is it possible that 10 doctors can't find out what I'm suffering from?”

At that time, one of Arafat’s doctors told me that the leader had developed an infection in his blood that ultimately affected his internal organs.

When I visited Ramallah in those last days of Arafat’s regime, I found that people who spent a lot of time with the leader were deeply concerned. Not about Arafat’s blood, but about his state of mind. He went a year without washing the scarf he used to tie around his neck like an Ascot, one of them said. Another said he rambled about the old days in Beirut, whenever an aide would try to get him to address the disastrous situation of the Palestinian towns, which were subject to constant raids by the Israeli army.

It always struck me that one of them might have decided to put an end to the PLO chairman’s long decline.

When Arafat took a final turn for the worse, his long-time doctor, Ashraf al-Kurdi, prepared to come to him from his home in Jordan. Top PLO officials called Kurdi and told him not to make the journey to Ramallah.

Instead, Abbas and a few other PLO chiefs went with Arafat. They stayed by his side until he was dead (and then another week, perhaps, until they actually decided to announce his death).

Then they spent $1.75 million on his mausoleum. When he unveiled the completed structure in November 2007, Abbas said: “We will continue on the path of the martyred President Yasser Arafat.”

What kind of martyrdom it was, perhaps only Abbas knows.

Just like the (good?) old days

With US diplomats roaming the streets of Jerusalem, it's like the intifada never happened.

By Matt Beynon Rees - GlobalPost

JERUSALEM — It’s like the intifada never happened.

American diplomats mobbed the streets of Jerusalem this week. Even Iran point man Dennis Ross, whose sad-sack demeanor was a frequent feature of the Oslo peace process, stopped by to keep the U.S. defense secretary, the Mideast peace envoy, and the national security adviser company.

Meanwhile, in Palestinian politics, where hatred of Israel once brought everyone together for secret terror summits, Hamas again hates Fatah, which hates Hamas and also dislikes itself. In Israel, the two most powerful men are Benjamin Netanyahu and Ehud Barak.

Just like the old days. Before the five years of violence known as the intifada that began in September 2000, when Palestinian riots turned into gunbattles and the Israeli army reoccupied all the Palestinian towns it had evacuated during the previous seven years of the peace process.

Except there’s one reminder this week that the intifada actually did take place: Fouad Shoubaki is still screwed.

The man who ran military procurement and budgets for Yasser Arafat was convicted by an Israeli military court Wednesday of handing on $7 million worth in arms to the Al Aqsa Martyrs’ Brigades, which used the weapons to kill Israelis during the intifada.

The court also found Shoubaki guilty of paying $125,000 (from Arafat) to fund the voyage of a ship called the Karine A. When Israeli commandos from the Shayetet 13 — the equivalent of the Navy Seals — captured the Karine A in January 2002, it was carrying 50 tons of guns, missiles and material, loaded on board by Hezbollah operatives off the Iranian coast.

Though the intifada was 15 months old at the time the Karine A was captured, many in Washington and other world capitals became convinced that Arafat really did think he was at war with Israel. They stopped talking about “putting the peace process back on track.” Until recently.

The Palestinians put Shoubaki in jail in Jericho. The Israelis said all along that he was just a fall guy being held for appearances sake. In 2006, when it seemed Shoubaki might be released, the Israelis raided the Jericho jail and captured him. His trial lasted three years.

In the court, Shoubaki claimed to “have sought peace between the Palestinians and the Israelis and to build neighborly relations.” He said he was close to current Palestinian president Mahmoud Abbas, who’s considered a moderate in favor of peace talks with Israel (although he won’t talk to them just now).

But the court also heard that Shoubaki admitted some unneighborly actions during his interrogation by the Israeli domestic security service, the Shin Bet.

He was the go-between for Arafat’s contacts with Imad Mughniya, a top Hezbollah operative believed to have been behind the 1983 bombings of the U.S. Marine barracks and the U.S. Embassy in Beirut that killed more than 300 people. (Mughniya, whose bloody resume was much longer than can be detailed here, died in a car bomb in Damascus in February last year. Hezbollah factions, the Syrian government and the Israeli Mossad have all been blamed for his killing at one time or another.)

Shoubaki maintained, under interrogation, that he was just following orders. Arafat signed off on all the payments and it was a time of war, so Shoubaki can’t be held responsible, he argued. At his sentencing next month, the 70-year-old looks certain to get life.

Shoubaki’s activities seem to belong to a distant era, now that the Palestinian Authority security forces in the West Bank are following orders from their U.S. adviser, Gen. Keith Dayton, and Israeli officials describe cooperation as better even than during the Oslo period.

But it’s only a few years, really. Many of the same people are in power on both the Israeli and Palestinian sides. The same is true of much of the U.S. negotiating team. While they may not be capable of messing up on the scale Arafat managed in the early years of the intifada, there are signs that what seemed like momentum two months ago is fizzling.

The U.S. had demanded a freeze on construction in the Israeli settlements in the West Bank. Special envoy George Mitchell was here this week trying to get the Israelis to agree to a partial freeze. Israeli officials say the Americans are now attempting to get the Israelis to stop some construction in return for a removal of restrictions in certain ultra-Orthodox Jewish settlements.

But such new construction will take up Palestinian land just like the settlements whose expansion Israel is on track to halt. And the settlements which will get the green light are where the building is most frenetic, because of high birth rates among ultra-Orthodox communities.

The Palestinians, too, are repeating the mistakes that led them to bring the Oslo edifice down about their own heads. A meeting set for next week in Bethlehem to reform the ruling Fatah faction may not go ahead, and even if it does it won’t sweep away as many corrupt old hacks as the party’s young guard wants.

Last time that happened, the young leaders decided to destroy the peace process, which formed the power base of the old cadres, so that Arafat would have to turn to them for support. It didn’t work out, of course, but there are plenty who might want to have another shot.

Shoubaki may be going to jail forever, but his old pals might soon need his Rolodex.

By Matt Beynon Rees - GlobalPost

JERUSALEM — It’s like the intifada never happened.

American diplomats mobbed the streets of Jerusalem this week. Even Iran point man Dennis Ross, whose sad-sack demeanor was a frequent feature of the Oslo peace process, stopped by to keep the U.S. defense secretary, the Mideast peace envoy, and the national security adviser company.

Meanwhile, in Palestinian politics, where hatred of Israel once brought everyone together for secret terror summits, Hamas again hates Fatah, which hates Hamas and also dislikes itself. In Israel, the two most powerful men are Benjamin Netanyahu and Ehud Barak.

Just like the old days. Before the five years of violence known as the intifada that began in September 2000, when Palestinian riots turned into gunbattles and the Israeli army reoccupied all the Palestinian towns it had evacuated during the previous seven years of the peace process.

Except there’s one reminder this week that the intifada actually did take place: Fouad Shoubaki is still screwed.

The man who ran military procurement and budgets for Yasser Arafat was convicted by an Israeli military court Wednesday of handing on $7 million worth in arms to the Al Aqsa Martyrs’ Brigades, which used the weapons to kill Israelis during the intifada.

The court also found Shoubaki guilty of paying $125,000 (from Arafat) to fund the voyage of a ship called the Karine A. When Israeli commandos from the Shayetet 13 — the equivalent of the Navy Seals — captured the Karine A in January 2002, it was carrying 50 tons of guns, missiles and material, loaded on board by Hezbollah operatives off the Iranian coast.

Though the intifada was 15 months old at the time the Karine A was captured, many in Washington and other world capitals became convinced that Arafat really did think he was at war with Israel. They stopped talking about “putting the peace process back on track.” Until recently.

The Palestinians put Shoubaki in jail in Jericho. The Israelis said all along that he was just a fall guy being held for appearances sake. In 2006, when it seemed Shoubaki might be released, the Israelis raided the Jericho jail and captured him. His trial lasted three years.

In the court, Shoubaki claimed to “have sought peace between the Palestinians and the Israelis and to build neighborly relations.” He said he was close to current Palestinian president Mahmoud Abbas, who’s considered a moderate in favor of peace talks with Israel (although he won’t talk to them just now).

But the court also heard that Shoubaki admitted some unneighborly actions during his interrogation by the Israeli domestic security service, the Shin Bet.

He was the go-between for Arafat’s contacts with Imad Mughniya, a top Hezbollah operative believed to have been behind the 1983 bombings of the U.S. Marine barracks and the U.S. Embassy in Beirut that killed more than 300 people. (Mughniya, whose bloody resume was much longer than can be detailed here, died in a car bomb in Damascus in February last year. Hezbollah factions, the Syrian government and the Israeli Mossad have all been blamed for his killing at one time or another.)

Shoubaki maintained, under interrogation, that he was just following orders. Arafat signed off on all the payments and it was a time of war, so Shoubaki can’t be held responsible, he argued. At his sentencing next month, the 70-year-old looks certain to get life.

Shoubaki’s activities seem to belong to a distant era, now that the Palestinian Authority security forces in the West Bank are following orders from their U.S. adviser, Gen. Keith Dayton, and Israeli officials describe cooperation as better even than during the Oslo period.

But it’s only a few years, really. Many of the same people are in power on both the Israeli and Palestinian sides. The same is true of much of the U.S. negotiating team. While they may not be capable of messing up on the scale Arafat managed in the early years of the intifada, there are signs that what seemed like momentum two months ago is fizzling.

The U.S. had demanded a freeze on construction in the Israeli settlements in the West Bank. Special envoy George Mitchell was here this week trying to get the Israelis to agree to a partial freeze. Israeli officials say the Americans are now attempting to get the Israelis to stop some construction in return for a removal of restrictions in certain ultra-Orthodox Jewish settlements.

But such new construction will take up Palestinian land just like the settlements whose expansion Israel is on track to halt. And the settlements which will get the green light are where the building is most frenetic, because of high birth rates among ultra-Orthodox communities.

The Palestinians, too, are repeating the mistakes that led them to bring the Oslo edifice down about their own heads. A meeting set for next week in Bethlehem to reform the ruling Fatah faction may not go ahead, and even if it does it won’t sweep away as many corrupt old hacks as the party’s young guard wants.

Last time that happened, the young leaders decided to destroy the peace process, which formed the power base of the old cadres, so that Arafat would have to turn to them for support. It didn’t work out, of course, but there are plenty who might want to have another shot.

Shoubaki may be going to jail forever, but his old pals might soon need his Rolodex.

A bloated, stinking mass of Ariel Sharon

The aptly-named Ariel Sharon Park

Opinion: Israel’s biggest garbage dump is being redeveloped — and renamed.

By Matt Beynon Rees - GlobalPost

TEL AVIV — A bloated, stinking mass that everyone would have preferred not to have to see, but which nonetheless was thrust upon them. A sight that shamed the people of Israel and ought to have been marginalized, but which was situated right in the center of the nation and was impossible to ignore. In the end, it seems, people will decide they were too harsh in their judgments.

You might think I’m talking about the former Israeli prime minister, Ariel Sharon, who endured international isolation and domestic opprobrium for his uncompromising military and political career, only to end up grudgingly appreciated for his acceptance that Israel had to end its occupation of Palestinian land.

But I’m not. I’m referring to Ariel Sharon Park.

Israel’s biggest garbage dump, Hiriya, is being redeveloped as a park. This week plans are being finalized to include a 50,000-seat amphitheater as part of the project.

Laid out by German and Israeli designers, it’s trumpeted by the Israeli government as bigger than New York City's Central Park and the biggest urban park built anywhere in the world during the last century.

Hiriya’s switch from eyesore to attraction is a strange parallel to the career of Sharon. Now 81, he lies in a persistent vegetative state in Sheba Medical Center in a Tel Aviv suburb.

The prime minister had only just begun to convince world leaders that he was no demon and might in fact be the best hope for peace between Israel and the Palestinians, when he fell into a coma after a stroke in January 2006. He has never recovered.

Some might say Israeli politics haven’t either. Shortly before his stroke, Sharon had launched a new political party, Kadima. It attracted many centrist legislators from other parties and looked set to dominate the Knesset.

Sharon’s central policy at that time was to pull out of many of Israel’s West Bank settlements, just as he had done from its Gaza Strip settlements in 2005.

With Sharon off the scene, Israel was led by Ehud Olmert, a man without his predecessor’s military flair and experience. Olmert messed up an unnecessary war with Hezbollah in Lebanon in mid-2006. His approval ratings went — given polling margins of error — to zero, and all chances of a West Bank pullout went out the window.

The result: Israel’s current right-wing government, and the stubborn silence of the Palestinians who refuse to negotiate with it until the continued expansion of the settlements is frozen.

When I first came to Israel in 1996, Sharon’s career looked to be over. He’d been ostracized for his controversial role in Israel’s 1982 Lebanon invasion and for failing to prevent the massacre of Palestinian refugees by Israel’s Lebanese Christian allies.

Even the new right-wing prime minister, Benjamin Netanyahu, didn’t want him in his cabinet back then and cobbled together a new set of minor ministerial powers for Sharon, to buy off some of his friends in the Knesset. Later Sharon clawed his way into the Foreign Ministry and then to the prime minister’s office.

Hiriya, at that time, was just as unpopular as Sharon. It was the first sight I had of Israel when I left Ben-Gurion International Airport on the main Jerusalem-Tel Aviv Highway. I looked out of the taxi window at the 260-feet-high hill rising steeply out of the otherwise billiard-table flatness of the Dan plain and said, “Oh, a mountain? In the middle of a flat place like this?”

“It’s a mountain,” said my driver, with the kind of cynical sneer specific to Israelis that I would come to know so well in the ensuing decade. “A mountain of our shit.”

In fact, 112 acres of ordure a half-mile square, 565 million cubic feet of garbage gathered there since 1952, pumping out methane, carbon dioxide and sulfur. Bulldozers (also a common nickname for the unyielding Sharon) trundled about on top of the mound, shunting the trash into lanes and looking like childrens’ toys on the enormous excrescence. Flocks of gulls swarmed like flies on a giant reclining rhino.

Such dense clouds of gulls that they caused several engine failures when they collided with jets taking off or landing at Ben-Gurion over the years — one of the reasons for closing the dump in 1998.

As Prime Minister, Sharon supported the idea of turning Hiriya into a park. He blocked attempts to develop the area for housing.

There are now three recycling plants beside the hill of garbage, so in the end its bulk will be trimmed. Its greenhouse gases will eventually be used to create the electricity to light the amphitheater for nighttime shows. The whole park will cost $250 million and is expected to be completed by 2014.

Organizers have said the site will be an international tourist draw, like Stonehenge.

Well, there will be some archaeological sites inside the park—though not perhaps of Stonehenge’s magnitude. Some of them are from the ancient town of Bnei Brak, which used to stand in the Hiriya area during the Talmudic period.

This archaeological park will be named after Menachem Begin, the prime minister who was drawn into the Lebanon War by his defense minister, Sharon. When he saw how the war turned out, Begin fell into a depression — also prompted by the death of his wife — and lived in seclusion until his death in 1992.

Begin will be a sideshow to Sharon’s main billing at the park. It’s only a shame that Sharon’s stroke hit before he could make his disastrous conduct of the Lebanon War a footnote to his closing down of the Israeli colonies in the West Bank.

Opinion: Israel’s biggest garbage dump is being redeveloped — and renamed.

By Matt Beynon Rees - GlobalPost

TEL AVIV — A bloated, stinking mass that everyone would have preferred not to have to see, but which nonetheless was thrust upon them. A sight that shamed the people of Israel and ought to have been marginalized, but which was situated right in the center of the nation and was impossible to ignore. In the end, it seems, people will decide they were too harsh in their judgments.

You might think I’m talking about the former Israeli prime minister, Ariel Sharon, who endured international isolation and domestic opprobrium for his uncompromising military and political career, only to end up grudgingly appreciated for his acceptance that Israel had to end its occupation of Palestinian land.

But I’m not. I’m referring to Ariel Sharon Park.

Israel’s biggest garbage dump, Hiriya, is being redeveloped as a park. This week plans are being finalized to include a 50,000-seat amphitheater as part of the project.

Laid out by German and Israeli designers, it’s trumpeted by the Israeli government as bigger than New York City's Central Park and the biggest urban park built anywhere in the world during the last century.

Hiriya’s switch from eyesore to attraction is a strange parallel to the career of Sharon. Now 81, he lies in a persistent vegetative state in Sheba Medical Center in a Tel Aviv suburb.

The prime minister had only just begun to convince world leaders that he was no demon and might in fact be the best hope for peace between Israel and the Palestinians, when he fell into a coma after a stroke in January 2006. He has never recovered.

Some might say Israeli politics haven’t either. Shortly before his stroke, Sharon had launched a new political party, Kadima. It attracted many centrist legislators from other parties and looked set to dominate the Knesset.

Sharon’s central policy at that time was to pull out of many of Israel’s West Bank settlements, just as he had done from its Gaza Strip settlements in 2005.