Matt Rees's Blog - Posts Tagged "happiness"

Whingers and Warm Guns: Happy-Guru Eric Weiner's Writing Life

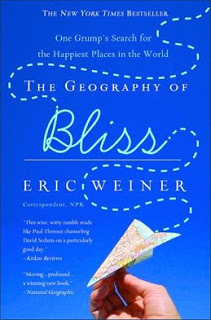

What’s happiness? A large income, Jane Austen said. Absolute ignorance, according to the delightfully morbid Grahame Greene. Or John Lennon’s less delightfully morbid warm gun. Whatever else it is, happiness is done to death. But where it is? That’s something new. The genius of Eric Weiner’s New York Times bestseller “The Geography of Bliss: One Grump’s Search for the Happiest Places in the World” is to change the way of searching for happiness. Instead of looking for ways to make himself happy (the typically American individualistic approach to joy), he went out to find places where other people were happy. That way the former NPR correspondent (I got to know him when he was Mideast bureau chief, but he was based in India, too, for a time) was able to identify broader characteristics of a society that create happiness. He found, of course, that being Swiss helps (they trust everyone around them and therefore don’t have to worry and watch their backs). Being Moldovan on the other hand definitely doesn’t help -- everyone cheats, nothing's fair = miserable place. On his journey Eric also ditched email. But he broke that rule for the sake of my blog, and I’m glad he did.

How long did it take you to get published?

It took me three weeks to find an agent and publisher. It took twelve years for me to settle on an idea that I was passionate about.

Would you recommend any books on writing?

No. I think the best way to learn to write is to write. Reading (everything and anything) helps, too. So does coffee.

What’s a typical writing day?

I wake up bright and early, and by 8:00 a.m. settle into my office. Then I check my e-mail. Then I check Facebook. Then I check a few of my favorite blogs. Then I break for lunch. Usuallly, after lunch, I will do some actual writing before calling it a day.

Plug your latest book. What’s it about? Why’s it so great?

You're asking a writer to plug his own work? Okay, if you insist. My book, The Geography of Bliss, is brilliant because it takes a fairly tried subject, happiness, and gives it a new twist. Most happiness books focus on the what of happiness; I was interested in the where. Which are the world's happiest countries and what can we learn from them? And--did I mention?--the writing is brilliant! Funny and serious at the same time. I would highly recommend it. Really.

How much of what you do is:

a) formula dictated by the genre within which you write?

b) formula you developed yourself and stuck with?

c) as close to complete originality as it’s possible to get each time?

Mainly b), I think, with a smattering of c). My genre, broadly speaking, is travelogue. It is an odd, self-loathing genre. Many of the great travel writers don't like to be called travel writers. I think that's because travel writing sounds fluffy and inconsequential. At least bad travel writing is like that. Good travel writing is simply good writing that happens to use place as its main construct. In my work, I try to fashion a slightly new genre, the travelogue of ideas. In that sense, my book isn't really travel book at all. It's a book about the nature of happiness that uses geography as a way to get at this mystery.

Where is your favorite place to write?

I like coffee shops. The background din, oddly, helps me focus. After a while, though, I get antsy and feel the need to move. I might write in two or three different places in a single day. After all, I am a travel writer. Place matters.

Who is your favorite travel writer?

Jan Morris. She can get to the heart of a place in a few sentences. She is opinionated, but not obnoxiously so. She puts herself in her writing but never gets in the way of a good story. And she can be funny in all the right places.

What do you do if you are stuck?

I drink more coffee. If that doesn't work, (and it usually doesn't) I go for a walk. If that doesn't work (and it usually doesn't) I read what I have written aloud. I tend to write for the ear, and reading aloud can help me regain my rhythm. Also, I recently discovered a wine called "Writer's Block." It's a very nice Zinfandel.

What do you read for pleasure?

I like big fat books that tackle big fat topics. I'm currently reading Peter Watson's Ideas; A History of Thought and Invention from Fire to Freud. It's easily 800 pages. I'm still in the fire bit.

How much research is involved in each of your books?

An awful lot. For The Geography of Bliss, I read everything I could get my hands on about happiness, from Aristotle to Marty Seligmen, the poo-bah of the "science of happiness." I camped out at a university library for weeks on end. For a while, I was concerned that I was over-researching, but now I dont' think there is such a thing. Many morsels from my research made their way into the final manuscript.

What’s your experience with being translated?

My book has been translated into 13 languages, The publishers send me copies, which is nice. I can't understand a word of them,. for all I know they did a terrible job of translating. But they look nice on my bookshelf. Especially the Korean edition. Very colorful.

Do you live entirely off your writing?

I do make a living off my writing. I consider myself very fortunate.

How many books did you write before you were published?

This is my first one. Non-fiction, though, is a lot easier to get published than fiction.

What’s the strangest thing that happened to you on a book tour?

I had just completed an interview with a radio station in Portland, Oregon, when the interviewer said, "That was really great, Do you want to smoke some weed?" It's true. I might have taken him up on it, but I had a book reading in a couple of hours, so I politely declined.

What’s your weirdest idea for a book you’ll never get to publish?

I'd like to write a travel book about time travel. I would go back in time to an age when there still were undiscovered places to explore and write about them. I'd also buy some choice real estate in Manhattan. Then I'd travel back to the present and live large.

Published on June 10, 2009 01:11

•

Tags:

east, eric, happiness, interviews, journalism, life, literature, middle, nonfiction, weiner, writing

When poets do the talking

A new book examines the lives of Palestinian poets

By Matt Beynon Rees - on GlobalPost

JERUSALEM — Whenever Palestinian and Israeli artists get together for public “dialogues,” it always seems to end with the Israelis saying, “We’re sorry,” and the Palestinians responding, “Screw you anyway.”

That was how it went at a literary conference in the Jerusalem monastery at Tantur where I moderated a couple such discussions two years ago.

Except for the opening session.

The day began with a reading by Taha Muhammad Ali, a poet who lives in Nazareth, and his translator Peter Cole, a native of New Jersey and now a Jerusalem resident. Taha, who was then 75 years old, recited several of his poems, which Cole read in English.

Taha was avuncular and bumbling, endearing him to the audience of international publishers. But his poetry was deceptively incisive and personal, transcending the sense of victimization that would color the panel discussions for the rest of the day. Somehow he seemed to be the only one that day who had anything real to say.

"Don’t aim your rifles / at my happiness, / which isn’t worth / the price of a bullet,” Taha read. “My happiness bears / no relation to happiness.”

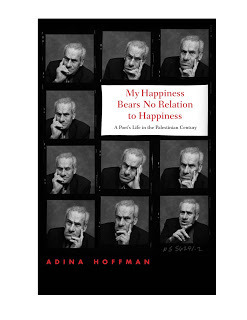

The warmth and intelligence of Taha’s readings drove Adina Hoffman, a Jerusalem-based writer and wife of translator Cole, to plan a biography of the poet (“My Happiness Bears No Relation to Happiness: A Poet’s Life in the Palestinian Century,” Yale University Press). Only then did she discover that, despite all the ink spilled on the Palestinian issue over the years, no one had ever written a biography of any Palestinian poet.

So she expanded the book. Using Taha as the central figure, she constructed the intersecting life stories of writers as diverse as Mahmoud Darwish, the "national" poet whose death last year prompted weepy editorials around the world, and Rashid Hussein, the most original and tortured of them, who died alone and drunk in New York 30 years ago.

Hoffman’s book is a way for readers to get around the usual stereotypes of the Palestinians as they’re portrayed in the cliches of their political struggle. She looks at the fascinating day-to-day, emotional history of this troubled people as told through their dynamic poetic culture.

“One can get a different idea of Palestinians as people through the history of their poets,” Hoffman told GlobalPost. “Poetry and poets occupy such an essential role in Palestinian society: Throughout much of the last century, poetry has served as one of the most important means of political and social expression for the Palestinian people — and the poets who’ve given voice to that impulse are central to the culture.”

Their poetry forms a gap in our knowledge of the Palestinians because of the way reporters cover their story — focusing on the violence and pyrotechnics and screaming, rather than on what people actually feel beneath it all.

“So much of the news coverage of the Palestinian story winds up treating them as a faceless group — whether a group of terrorists or a group of downtrodden victims,” Hoffman said. “I wanted to offer a view of Palestinian life that depicted as precisely and deeply as possible the full human range of feeling and complexity that exist in that culture.”

Hoffman uses Taha’s story as the framework for an alternative telling of Palestinian history, eschewing the slogans of political leaders and focusing on the soul-searching of young poets and writers.

You might think that would draw you away from reality into the realms of fantasy. But, as I’ve discovered in writing a series of Palestinian crime novels based on real stories I’ve reported, it’s only when a writer examines the underlying emotions of his subject that he uncovers the truth.

“The truest poetry is the most feigning,” Shakespeare wrote. Journalists, from whom we’re accustomed to getting our information about the Palestinians, aren’t supposed to be “feigning” at all. The result: no poetry and, often, no truth.

Hoffman’s telling of Taha’s story is particularly important because his life encompasses almost every element of the Palestinian experience. Born in 1931 in the village of Saffuriya, his family was expelled during the 1948 war which founded Israel. They fled to Lebanon, snuck back to Nazareth, and became refugees within Israel. He saw the devastation of war, too, on a visit to Lebanon in search of his childhood sweetheart.

Taha supported his family by running a souvenir shop for tourists visiting the town where Jesus grew up. He slowly developed a literary style that was at odds with traditional, highly formulaic Arab verse. Neither did he follow the incantatory public style of Darwish and the best known Palestinian poets.

Hoffman observes that Taha’s largely free verse (which many Palestinians rejected as simple prose chopped up into lines) is based around a classical Arabic concept of “a difficult, elusive, or even inscrutable simplicity.”

That simplicity is embodied in the poet’s peasant background, which Hoffman tells in vivid detail. Much of the book’s early chapters are devoted to life in Saffuriya, before the village was replaced with an Israeli community.

But it isn’t yet another regurgitating of Palestinian suffering. Her portrait of the village illustrates the richness of life there, showing how the memory of Saffuriya was part of “the world that surrounded these poets and that inspired them to write,” as she said.

It’s the remembrance of that world that dominates Taha’s poetry even six decades after Saffuriya ceased to exist. Hoffman’s account preserves the memory by recounting it and by introducing readers to the poetry that grew out of it.