Matt Rees's Blog - Posts Tagged "philip-marlowe"

Why's a Palestinian sleuth in Brooklyn?

I’ve been called the Dashiell Hammett of Palestine, the John Le Carre of the Middle East, the James Ellroy of…Palestine, the Graham Greene of Jerusalem, and the Georges Simenon of the Palestinian refugee camps. Depends which review you happen to have read.

I’ve been called the Dashiell Hammett of Palestine, the John Le Carre of the Middle East, the James Ellroy of…Palestine, the Graham Greene of Jerusalem, and the Georges Simenon of the Palestinian refugee camps. Depends which review you happen to have read.Until now I’ve published three novels about Omar Yussef, my Palestinian schoolteacher/sleuth. Omar has been described as the Philip Marlowe of the Arab street, the Hercules Poirot of the Near East, Sam Spade fed on hummus, and Miss Marple crossed with Yasser Arafat.

Why then is my new Omar Yussef novel THE FOURTH ASSASSIN,/a> set in New York City? Not in the Middle East, the Near East, Palestine, the Levant, the Fertile Crescent, or any other place where Yasser may be fornicating with dear old Miss Jane Marple.

I lived in New York six years, until I came to Jerusalem in 1996. I know it better than any city outside the Middle East. I had a lot of fun in New York. Maybe too much fun. In no other place in the world can a young man so overindulge in the temptations originally offered in the city of Sodom. Which in reality is close to where I live now in Jerusalem. Though you wouldn’t know it to look at the place.

I know New York with my eyes closed. Literally. In my twenties, after leaving some bar or club, I blacked out on every line on the subway map.

I dated women from every borough of the city, from Westchester and upstate. From the 201 area code (dare I say, New Jersey.)

I married a girl from the North Shore of Long Island, and in my continuing effort to know New York in all its facets, when we divorced, I married a beautiful woman from the South Shore of Long Island.

But each time I returned, no matter how well I thought I knew the place, New York seemed different. The change became most apparent after 9/11. I wanted to understand it through the eyes of Omar Yussef.

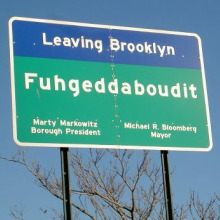

That’s why he finds himself in Brooklyn in THE FOURTH ASSASSIN. Visiting the area of Bay Ridge that has become known as “Little Palestine,” for the influx of Palestinian immigrants.

Little Palestine isn’t a community of Palestinian intellectual émigrés, such as sprang up in European capitals in the 1970s. It’s a new wave of young men mostly, saving to bring their families over, working two or more jobs. Theirs is a typical American immigrant story.

Except for the FBI agents going through their trash.

The Bureau didn’t uncover any broad conspiracy in Little Palestine. But it did add to the tensions between the Arab community and other New Yorkers after the attack on the Twin Towers.

That’s the situation into which I wanted to place Omar Yussef. Mutual distrust, after all, makes for good crime fiction.

In Brooklyn, it also happens to be real.

Published on February 11, 2010 23:51

•

Tags:

bay-ridge, brooklyn, crime-fiction, dashiell-hammett, fbi, fertile-crescent, georges-simenon, graham-greene, hercules-poirot, james-ellroy, jerusalem, levant, little-palestine, long-island, middle-east, miss-jane-marple, miss-marple, near-east, new-jersey, new-york, omar-yussef, palestine, palestinians, philip-marlowe, sam-spade, the-fourth-assassin, upstate-new-york, westchester-county, yasser-arafat

Love and the crime novel

The crime novel tradition seems to have little connection to love. Maybe sometimes love in a perverse sense is the spur to the murder at the heart of most crime novels – the spurned husband killing his wife, for example. But usually the detective is a loveless loner, pining without much hope like the great Marlowe for his true love to come along.

The crime novel tradition seems to have little connection to love. Maybe sometimes love in a perverse sense is the spur to the murder at the heart of most crime novels – the spurned husband killing his wife, for example. But usually the detective is a loveless loner, pining without much hope like the great Marlowe for his true love to come along.As I write more novels, I’ve noticed that love is at the heart of crime fiction. At least, mine, anyway.

Leonard Cohen sings that “love’s the only engine of survival.” It’s a good way to look at the crime novel. Rather than being a race to unravel the murder puzzle and nab the killer, I view the crime novel as the detective’s journey toward understanding about himself. And understanding, in my experience, comes only with the unfolding of love. You can finger the killer and take away the danger he poses, but unless your detective learns about love, emotionally he won’t survive the trauma of his closeness to death.

It may seem that I ought to have figured this out before now – I’m close to completion of the manuscript of my sixth novel, after all. But society hides the centrality of love behind strictures of finance and duty and work, and the format of the crime novel often plays the same role. So it’s only now, 400,000 words down the line, that it’s clear to me.

I started out thinking of crime novels as marked by plot – a murder, an investigation, a discovery of the bad guy – alongside a deeper emotional characterization of the hero and as many of the other characters as I could manage.

Then as my novels went on, the importance of relationships between the characters started to grow more sigificant in the way I conceputalized them. I realized that it was these relationship which gave the novel structure and meaning, rather than the Three Act concept (dilemma, discovery, resolution) of most writing texts. The Three Acts were the superstructure, if you like, but no more.

Read the rest of this post on my blog The Man of Twists and Turns.<\a>

Published on October 13, 2010 23:58

•

Tags:

bethlehem, brooklyn, crime-fiction, detective-fiction, leonard-cohen, new-york, omar-yussef, philip-marlowe, the-collaborator-of-bethlehem, the-fourth-assassin

Unpolished Fleming and Paranoid Mankell

I’ve seen two things in the last week that allowed me to compare something

I’ve seen two things in the last week that allowed me to compare somethingof the way crime writers used to appear in public and their present avatars.

It only made me wish for the good old days even more than I used to.

The comparison is between: a delightful radio chat on the BBC in 1958 between Raymond Chandler and Ian Fleming; and a load of paranoid weirdness from Henning Mankell.

First, Chandler and Fleming. Listen to their talk. I rarely bother listen to

an entire half hour of anything online, but I’m telling you this is

beautiful. Both of them are unpolished as all hell. For anyone who’s been to

a book fair and seen the well-honed wisecracks and calibrated personae of today’s authors, this’ll be refreshing.

When Fleming asks Chandler to explain how a hit is done in America (which

surely seemed like a very dangerous place to the average BBC listener of

half a century ago), gruff old Ray puffs on his pipe and spins an unlikely tale of gunmen brought to New York from that den of iniquity, Minneapolis. It

impresses Fleming so much that he refers to it in summing up the broadcast

as something very enlightening and shocking and underground that Chandler

has given us.

But most of all from Chandler’s side there’s the news that he intended

another Marlowe novel in which the great shamus would be married (see the

end of “Playback”) and, though he’d love his wife, he’d be frustrated by her

friends and the ease with which he lives.

Fleming, meanwhile, is very British and self-deprecating, pointing out

several times that his novels are pale shadows of what Chandler writes. In

turn, Chandler is amazed that Fleming writes a novel in two months during

his annual Jamaica vacation, having never written one faster than three

months himself. He then opines that “you starve 10 years before even your

publisher knows you’re any good.” Amen to that.

This truly beautiful conversation – hearing the voices of these fellows is

priceless in itself – was in stark contrast to Henning Mankell’s appearance

in an Israeli newspaper last week.

The starting point for Mankell’s piece was his deportation from Israel a

year ago. He was among the pro-Palestinian activists aboard a flotilla of

ships headed for Gaza, which was intercepted by Israeli commandoes. Aboard one of the ships, the commandoes and activists fought and nine activists were killed. Mankell was among those brought back to Israel on the boats and then deported.

His article in Ha’aretz last week goes through the story of a Facebook page

opened in his name. It declared support for the Lebanese Islamists of

Hezbollah and other positions he claims not to share. Facebook took the site

down twice at Mankell’s request. Mankell wonders who was behind the Facebook page.

To anyone who’s been in the Middle East, the most obvious answer is: a

Palestinian supporter saw that Mankell was on their side and decided to

hijack his name for some other causes to which he or she thought Mankell

might be inclined. Or at least that they’d be causes to which readers might

assume Mankell was inclined, knowing his position on Palestine.

But no. With a circuitous logic never apparent in his plodding Wallander

novels, Henning tells us that he heard the Israeli government wanted to use

social media to attack its enemies. Is this behind the “Henning Mankell”

Facebook page? Twice he writes: “Who would benefit from this?”

Read the rest of this post on my blog The Man of Twists and Turns.

Published on June 23, 2011 05:46

•

Tags:

bbc, crime-fiction, gaza, gaza-flotilla, henning-mankell, ian-fleming, inspector-wallander, israel, james-bond, palestine, philip-marlowe, raymond-chandler

Re-reading Ray

I happened to read a few crappy books in a row of late. So I did what I always do when I can’t afford for the next book I get into to disappoint: I re-read a Raymond Chandler.

I happened to read a few crappy books in a row of late. So I did what I always do when I can’t afford for the next book I get into to disappoint: I re-read a Raymond Chandler.I picked “The Long Goodbye” off the shelf, because it’s my favorite. From the very first page, where Marlowe finds Terry Lennox falling drunk out of a Rolls Royce Silver Wraith in front of a club called The Dancers, I find myself hooked once again: “The girl gave him a look which ought to have stuck at least four inches out of his back. It didn’t bother him enough to give him the shakes.”

Chandler is, for me, the greatest of writers. Taken with Hammett, I’d say he did everything for American literature that people always assume Hemingway did: made things simple, direct, tough and stark. But unlike Hemingway (and like Hammett), he had the gruff sense of humor of a man who didn’t quite buy into the system (he wasn’t a Communist like Hammett, but he’d lived in England and been in the Canadian airforce, which made him less than conventional). That’s why he wrote crime novels, I think. It’s an outsider’s genre, the writing venue of a man or woman who sees through things and yet remains positive enough to bother putting pen to paper.

Chandler, like Marlowe, seems to have “felt as out of place as a cocktail

onion on a banana split.” Frequently, so have I, when I’ve been among the

corporate or the gilded of this world –– and I have spent many an

uncomfortable day, month or year in those scurrilous circles. That, in

fact, may be why I’m a writer. Certainly it helps me cope with the weird

status a writer holds today, threatened and undervalued, and yet cherished

(though not always enough for someone to buy your book and pay for your

kids to go to college.)

Ray understood all that. In his essays he writes about how banal commercial

British cosy mysteries “really get me down.” In his interviews, he

complained that “you starve to death for ten years before your publisher

realizes you’re any good.”

Yes, Ray’s my man.

More posts by Matt Rees. More about Matt's books.

Published on December 01, 2011 02:29

•

Tags:

crime-fiction, detective-fiction, noir, philip-marlowe, raymond-chandler

Best First Paragraphs in Crime Fiction: Part 2

I’m writing this in a plain office in the corner of a building that was described by the realtor as “exclusive,” though it doesn’t exclude despondent ultra-Orthodox Jews panhandling for cash, plumbers who break all the pipes you hadn’t called them to fix, or the cheerful lady who lets her dog pee in the elevator. There’s the hum of heavy traffic from the road below and a view across the valley of brake lights on a highway where no one ever seems to move. The air is clear enough up here that I usually only smell me, sweating through the desert heat, except when the garbage truck empties the trashcans and sends up a rotten fruit ripeness, or when the khamsin blows and I can smell the dirt on the hot wind. There’s a mosquito in here, but the bastard isn’t friendly enough to show himself. When he does, I’ll do what people in the Middle East do best. There are already spots of my blood across the whitewash where his brothers and sisters felt the thick side of my fist.

I’m writing this in a plain office in the corner of a building that was described by the realtor as “exclusive,” though it doesn’t exclude despondent ultra-Orthodox Jews panhandling for cash, plumbers who break all the pipes you hadn’t called them to fix, or the cheerful lady who lets her dog pee in the elevator. There’s the hum of heavy traffic from the road below and a view across the valley of brake lights on a highway where no one ever seems to move. The air is clear enough up here that I usually only smell me, sweating through the desert heat, except when the garbage truck empties the trashcans and sends up a rotten fruit ripeness, or when the khamsin blows and I can smell the dirt on the hot wind. There’s a mosquito in here, but the bastard isn’t friendly enough to show himself. When he does, I’ll do what people in the Middle East do best. There are already spots of my blood across the whitewash where his brothers and sisters felt the thick side of my fist.If that sounds like a spoof, you surely know who I’m caricaturing. We decided last week that you couldn’t do much better than the opening paragraph of Hammett’s “Red Harvest” for an introduction to the narrative voice, narrator, place and tone of the entire novel. But if anyone could beat it, we’d have to look at Raymond Chandler.

The grumpy god of the gumshoe genre claimed not to have much time for the

idea of a classic in crime writing. In one of his essays, he wrote that contemporary writers who aimed for historical fiction, social vignette, or broad canvas would never surpass “Henry Esmond”, “Madame Bovary”, or “War and Peace”. Crime writers, on the other hand, would easily be able to

devise a better mystery than the ones detailed in “The Hound of the

Baskervilles” or “The Purloined Letter”. “It would be rather more difficult

not to,” he wrote.

Still, the poet with the pipe (okay, no more quirky names for Ray) proved

himself wrong. Or rather he proved that he was right not to focus so much

on the mystery element and, instead, to build a mysterious atmosphere and a sardonic sense of humor. From the opening paragraph.

This is how he starts a long 1950 short story called “Red Wind”:

There was a desert wind blowing that night. It was one of those hot dry

Santa Anas that come down through the mountain passes and curl your hair

and make your nerves jump and your skin itch. On nights like that every

booze party ends in a fight. Meek little wives feel the edge of the carving

knife and study their husbands’ necks. Anything can happen. You can even

get a full glass of beer at a cocktail lounge.

Like the opening paragraph of “Red Harvest,” this gives us all the elements

we’d expect. It also tells you a lot about the narrator and his lifestyle.

The booze parties, and the sense of being gypped at the cocktail lounge.

But the opening paragraph which might be said to define an entire genre ––

and the sub-genres of attempts to copy the true representatives of the

genre, and also to parody it –– starts Chandler’s 1949 novel “The Little

Sister”:

Read the rest of this post on my blog The Man of Twists and Turns.

Published on December 21, 2011 23:12

•

Tags:

crime-fiction, dashiell-hammett, mysteries, noir-fiction, philip-marlowe, raymond-chandler

Why did Marlowe go into the bar?

Mrs. Rees has given me two lovely kids. She has enjoyed the presence of my parents. She even visited Wales with me. But I was never quite sure of her. Because she had only read one Raymond Chandler novel.

Mrs. Rees has given me two lovely kids. She has enjoyed the presence of my parents. She even visited Wales with me. But I was never quite sure of her. Because she had only read one Raymond Chandler novel.In an effort to make our marriage complete, I suggested this week she augment her reading of “The Big Sleep” by going through the remainder of Big Ray’s oeuvre. I tossed “Farewell, My Lovely” at her and she got going.

As I did so, I was just finishing a draft of my next novel. Part of writing, let us be frank, is anticipating what editors will say about it when it’s done. I decided to look at Chandler’s work in the light of the comments I get from agents and editors about my manuscripts – and from readers about the finished book. I wonder how he’d have responded?

For example, “Farewell, My Lovely” begins, as you may recall, with Marlowe outside a bar, watching a very large fellow. The large man enters and tosses another man out of the door. Then Marlowe says: “I walked along to the double doors [of the bar] and stood in front of them. They were motionless now. It wasn’t any of my business. So I pushed them open and looked in.”

There’s no way a contemporary editor or agent would go for that. “What?” they’d say. “Marlowe has no stake here. He needs to have a compelling reason to go through those doors.”

Of course, the reason Marlowe goes through those doors isn’t that Chandler didn’t do plots (as some allege.) It’s that Marlowe is somewhat comically interested in random things around him. He isn’t looking for trouble, but he’s attracted to places where he might encounter it – out of curiosity. He’s an anthropologist of low-life.

Now an anthropologist might work as a “series character” in today’s fiction. But he’d have to be a real anthropologist. Everyone has to have a reason for what they do. Their family must be at risk. Someone must want to kill them. Their identity has been mistaken and they must clear their names. You know what I mean.

No character is allowed to be interested in what’s happening around them and nothing more.

Partially that’s the result of the James Patterson-ization of the thriller/crime genre. Every chapter must have the clock ticking down to the dread event our hero has to prevent.

But it’s also because we’ve grown accustomed to being able to nail everything down in life in general. If you don’t know the answer to a question, look it up on the web and instantly you’ll have someone else’s answer, right or wrong.

A New York Times article this morning noted that Americans increasingly are employing two or even three computer screens on one desk to hold all the different web windows they want to have open before them. One poor monkey-minded lady (it’s a yoga/meditation reference, before you get offended, and it refers to the inability to focus on one thing) told the Times that when her third screen malfunctioned, she felt like she was missing out on the news (because she keeps news feeds on that screen.) Sounds like information-overload, rather than so-called “multi-tasking”? As for the proliferation of data before her on her desk: “I can handle it,” she said. Like any other addict.

But the best example of the changes in our society and the way they’re reflected in our fiction is this: in “The Big Sleep,” one of the characters is fished out of the sea, having been driven off a pier in a car. Chandler was later asked who killed that character. He replied, “I never figured that out.”

Try telling that to an editor or an agent or a reader today. It’d be a badge of incompetence.

But Chandler didn’t need to know. Neither do we.

There should be ambiguity and lacunae in our knowledge. We should learn only what we can focus on. That means looking at a single computer screen and not worrying about missing information as it zips meaninglessly across the web. It also means allowing our plots to maintain a focus on what’s important, and leaving the occasional loose end untied.

Published on February 09, 2012 01:59

•

Tags:

crime-fiction, detective-fiction, noir, philip-marlowe, raymond-chandler, writing

Why did Marlowe go into the bar?

Mrs. Rees has given me two lovely kids. She has enjoyed the presence of my parents. She even visited Wales with me. But I was never quite sure of her. Because she had only read one Raymond Chandler novel.

Mrs. Rees has given me two lovely kids. She has enjoyed the presence of my parents. She even visited Wales with me. But I was never quite sure of her. Because she had only read one Raymond Chandler novel.In an effort to make our marriage complete, I suggested this week she augment her reading of “The Big Sleep” by going through the remainder of Big Ray’s oeuvre. I tossed “Farewell, My Lovely” at her and she got going.

As I did so, I was just finishing a draft of my next novel. Part of writing, let us be frank, is anticipating what editors will say about it when it’s done. I decided to look at Chandler’s work in the light of the comments I get from agents and editors about my manuscripts – and from readers about the finished book. I wonder how he’d have responded?

For example, “Farewell, My Lovely” begins, as you may recall, with Marlowe outside a bar, watching a very large fellow. The large man enters and tosses another man out of the door. Then Marlowe says: “I walked along to the double doors [of the bar] and stood in front of them. They were motionless now. It wasn’t any of my business. So I pushed them open and looked in.”

There’s no way a contemporary editor or agent would go for that. “What?” they’d say. “Marlowe has no stake here. He needs to have a compelling reason to go through those doors.”

Of course, the reason Marlowe goes through those doors isn’t that Chandler didn’t do plots (as some allege.) It’s that Marlowe is somewhat comically interested in random things around him. He isn’t looking for trouble, but he’s attracted to places where he might encounter it – out of curiosity. He’s an anthropologist of low-life.

Now an anthropologist might work as a “series character” in today’s fiction. But he’d have to be a real anthropologist. Everyone has to have a reason for what they do. Their family must be at risk. Someone must want to kill them. Their identity has been mistaken and they must clear their names. You know what I mean.

No character is allowed to be interested in what’s happening around them and nothing more.

Partially that’s the result of the James Patterson-ization of the thriller/crime genre. Every chapter must have the clock ticking down to the dread event our hero has to prevent.

But it’s also because we’ve grown accustomed to being able to nail everything down in life in general. If you don’t know the answer to a question, look it up on the web and instantly you’ll have someone else’s answer, right or wrong.

A New York Times article this morning noted that Americans increasingly are employing two or even three computer screens on one desk to hold all the different web windows they want to have open before them. One poor monkey-minded lady (it’s a yoga/meditation reference, before you get offended, and it refers to the inability to focus on one thing) told the Times that when her third screen malfunctioned, she felt like she was missing out on the news (because she keeps news feeds on that screen.) Sounds like information-overload, rather than so-called “multi-tasking”? As for the proliferation of data before her on her desk: “I can handle it,” she said. Like any other addict.

But the best example of the changes in our society and the way they’re reflected in our fiction is this: in “The Big Sleep,” one of the characters is fished out of the sea, having been driven off a pier in a car. Chandler was later asked who killed that character. He replied, “I never figured that out.”

Try telling that to an editor or an agent or a reader today. It’d be a badge of incompetence.

But Chandler didn’t need to know. Neither do we.

There should be ambiguity and lacunae in our knowledge. We should learn only what we can focus on. That means looking at a single computer screen and not worrying about missing information as it zips meaninglessly across the web. It also means allowing our plots to maintain a focus on what’s important, and leaving the occasional loose end untied.

Published on February 09, 2012 01:59

•

Tags:

crime-fiction, detective-fiction, noir, philip-marlowe, raymond-chandler, writing