Matt Rees's Blog - Posts Tagged "middle-east"

Memories of blood and corpses

A foreign correspondent builds memories out of blood and corpses. Often they turn to nightmares.

While working on my second Palestinian crime novel, A Grave in Gaza, I sometimes wept as I wrote. I used to think that meant I was a damned good writer. Now I know it was my trauma, collected over a decade of monthly visits to Gaza, seeping onto the page.

I hope that makes it a better novel. I know it saved me from the creeping depression and sudden fear that sometimes gripped me when my mind would return to memories of burned bodies, scattered body parts, angry people who wanted to hurt me, the sound of bullets nearby from an unseen gun. It helped me understand what kind of man I really was.

Journalism can’t do that. It plunges you into other people’s traumas and, through the constant repetition of 24-hour cable news, seems to make those horrors part of our own lives. It pushes us to blame someone, to rage against them. To lash out, like traumatized people. To feel depressed.

I know. I’ve been a journalist based in Jerusalem for 13 years.

As the latest violence unfolded in Gaza, I wondered what keeps me here. When I largely quit journalism to write my novels three years ago, I could’ve gone to Tuscany, as I had always thought I would to do. I no longer needed the journalist’s daily proximity to the conflict. Even though for a decade previously I’d been as committed as any other journalist to learning every nuance of the conflict, I’ve since been weeks at a time without turning on the local news.

That’s why I’m still here.

News blots out real life. It makes Israelis and Palestinians seem like incomprehensible, bloodthirsty lunatics, ripping each other apart without cease. Living amongst them makes it clear that it’s the news that’s unreal, fashioned to quicken the pulse and shoot you up with adrenaline. By staying here, living a happy life among normal Palestinians and Israelis, I’ve beaten the bad dreams and the sudden rages. They exist only in a decade of dog-eared notebooks on my bottom shelf.

I’ve developed relationships over the years with people who’ve opened up their cultures to me, shown me a perspective on Gaza that’s beyond what you’d ever see in the newspaper.

Take my friend Zakaria, who lives in the northern Gaza Strip village of Beit Hanoun, a major battleground in the current fighting. Zakaria was for decades Arafat’s top intelligence man. I’ve seen him during hard times when he expected his home to be stormed by rival Palestinian factions; when he sent armed men to bring me to meet him in secret; when Israeli tanks took up positions at the edge of his olive grove. Times worthy of headlines.

But my deepest impression of him came when he jovially served me giant scoops of hummus laced with ground meat and cubes of lamb fat at breakfast. As a foreign correspondent, I’ve downed some rough meals (Bedouins once milked a goat’s udder directly into a glass and handed me the warm fluid to drink), but try raw lamb fat at 9 a.m. and see how you like it.

For Zakaria, the dish was a tremendous delicacy and a demonstration of his hospitality. The writer in me found the mannerisms with which he served me and his insistence that I eat a second plate just as revealing as his tension during moments of conflict.

Fiction is able to put across the true characteristics of my Palestinian friends--like Zakaria’s courtly hospitality--in a way that’s largely beyond journalism, with its headline focus on the literally explosive. I’ve filled my novels with those characteristics, because they remind me that the times when I felt threatened by violence were unnatural. They belong only to nightmares and they aren’t real any more.

I want to give my readers the true emotional experience of being among people who live in extreme situations, with all its traumas, but mostly its pleasures. For entertainment--sure, these are novels, not non-fiction tomes to be crammed down like cod-liver oil because they’re good for you. But also because if there’s a point to knowing about the world beyond our borders, it’s to see into the minds of other men and thus to better understand ourselves. Sometimes it might even save us from ourselves.

Matt Beynon Rees is the author of a series of Palestinian crime novels. The latest novel, The Samaritan’s Secret, was published in February (Soho Press).

While working on my second Palestinian crime novel, A Grave in Gaza, I sometimes wept as I wrote. I used to think that meant I was a damned good writer. Now I know it was my trauma, collected over a decade of monthly visits to Gaza, seeping onto the page.

I hope that makes it a better novel. I know it saved me from the creeping depression and sudden fear that sometimes gripped me when my mind would return to memories of burned bodies, scattered body parts, angry people who wanted to hurt me, the sound of bullets nearby from an unseen gun. It helped me understand what kind of man I really was.

Journalism can’t do that. It plunges you into other people’s traumas and, through the constant repetition of 24-hour cable news, seems to make those horrors part of our own lives. It pushes us to blame someone, to rage against them. To lash out, like traumatized people. To feel depressed.

I know. I’ve been a journalist based in Jerusalem for 13 years.

As the latest violence unfolded in Gaza, I wondered what keeps me here. When I largely quit journalism to write my novels three years ago, I could’ve gone to Tuscany, as I had always thought I would to do. I no longer needed the journalist’s daily proximity to the conflict. Even though for a decade previously I’d been as committed as any other journalist to learning every nuance of the conflict, I’ve since been weeks at a time without turning on the local news.

That’s why I’m still here.

News blots out real life. It makes Israelis and Palestinians seem like incomprehensible, bloodthirsty lunatics, ripping each other apart without cease. Living amongst them makes it clear that it’s the news that’s unreal, fashioned to quicken the pulse and shoot you up with adrenaline. By staying here, living a happy life among normal Palestinians and Israelis, I’ve beaten the bad dreams and the sudden rages. They exist only in a decade of dog-eared notebooks on my bottom shelf.

I’ve developed relationships over the years with people who’ve opened up their cultures to me, shown me a perspective on Gaza that’s beyond what you’d ever see in the newspaper.

Take my friend Zakaria, who lives in the northern Gaza Strip village of Beit Hanoun, a major battleground in the current fighting. Zakaria was for decades Arafat’s top intelligence man. I’ve seen him during hard times when he expected his home to be stormed by rival Palestinian factions; when he sent armed men to bring me to meet him in secret; when Israeli tanks took up positions at the edge of his olive grove. Times worthy of headlines.

But my deepest impression of him came when he jovially served me giant scoops of hummus laced with ground meat and cubes of lamb fat at breakfast. As a foreign correspondent, I’ve downed some rough meals (Bedouins once milked a goat’s udder directly into a glass and handed me the warm fluid to drink), but try raw lamb fat at 9 a.m. and see how you like it.

For Zakaria, the dish was a tremendous delicacy and a demonstration of his hospitality. The writer in me found the mannerisms with which he served me and his insistence that I eat a second plate just as revealing as his tension during moments of conflict.

Fiction is able to put across the true characteristics of my Palestinian friends--like Zakaria’s courtly hospitality--in a way that’s largely beyond journalism, with its headline focus on the literally explosive. I’ve filled my novels with those characteristics, because they remind me that the times when I felt threatened by violence were unnatural. They belong only to nightmares and they aren’t real any more.

I want to give my readers the true emotional experience of being among people who live in extreme situations, with all its traumas, but mostly its pleasures. For entertainment--sure, these are novels, not non-fiction tomes to be crammed down like cod-liver oil because they’re good for you. But also because if there’s a point to knowing about the world beyond our borders, it’s to see into the minds of other men and thus to better understand ourselves. Sometimes it might even save us from ourselves.

Matt Beynon Rees is the author of a series of Palestinian crime novels. The latest novel, The Samaritan’s Secret, was published in February (Soho Press).

Published on February 28, 2009 07:14

•

Tags:

gaza, israel, journalism, journalist, middle-east, palestine, palestinians

Guardian: Top 10 Arab-world novels

"The Arab literary world and Western publishing don't cross over much. The literature of the Arab world is largely unknown in the west, and even westerners who write about Arabs are sometimes seen as fringe, cult writers. That comes at a cost to the west, because literature could be such an important bridge between two cultures so much at odds. What we see of the Arab world comes from news reports of war and other madness. Literature would be a much more profound contact.

"I live in Jerusalem and write fiction about the Palestinians because it's a better way to understand the reality of life in Palestine than journalism and non-fiction. The books in this list, in their different ways, unveil elements of life across the Arab world that you won't see in the newspaper or on TV."

Published on January 13, 2010 23:17

•

Tags:

abdulrahman-munif, ala-al-aswany, algeria, arab, arab-fiction, arab-novels, british-newspapers, cairo, egypt, emile-habiby, ibrahim-nasrallah, iraq, israel, kanaan-makiya, lawrence-durrell, middle-east, naguib-mahfouz, palestine, palestinians, paul-bowles, tariq-ali, the-guardian, yasmina-khadra

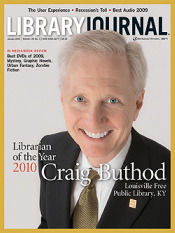

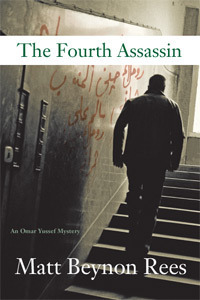

In new Palestinian crime novel NYC dangerous as West Bank

In the current Library Journal, my new Palestinian crime novel, THE FOURTH ASSASSIN (out Feb. 1) gets a good review that highlights the themes and implications beyond the resolution of the mystery. For those who have no copy of the magazine (in which case you may have missed Librarian of the Year -- Way to go, Craig Buthod of Louisville, Ky.) here's THE FOURTH ASSASSIN review: "In New York City for a UN conference, Omar Yussef goes to Bay Ridge, Brooklyn, home to a large Palestinian community, to visit his son and finds a beheaded body in his son's apartment. With no alibi, his son is arrested, and Omar finds that the streets of New York are as treacherous and dangerous as those of Bethlehem. VERDICT Journalist Rees's fourth Omar Yussef outing (after The Samaritan's Secret) exposes the political struggle among various Palestinian factions and demonstrates why it is so difficult to find a solution in the troubled region. His sleuth might miss the ancient streets of Bethlehem, but the hatred and tension of the Middle East follow the Palestinian wherever he goes."

In the current Library Journal, my new Palestinian crime novel, THE FOURTH ASSASSIN (out Feb. 1) gets a good review that highlights the themes and implications beyond the resolution of the mystery. For those who have no copy of the magazine (in which case you may have missed Librarian of the Year -- Way to go, Craig Buthod of Louisville, Ky.) here's THE FOURTH ASSASSIN review: "In New York City for a UN conference, Omar Yussef goes to Bay Ridge, Brooklyn, home to a large Palestinian community, to visit his son and finds a beheaded body in his son's apartment. With no alibi, his son is arrested, and Omar finds that the streets of New York are as treacherous and dangerous as those of Bethlehem. VERDICT Journalist Rees's fourth Omar Yussef outing (after The Samaritan's Secret) exposes the political struggle among various Palestinian factions and demonstrates why it is so difficult to find a solution in the troubled region. His sleuth might miss the ancient streets of Bethlehem, but the hatred and tension of the Middle East follow the Palestinian wherever he goes."

Published on January 19, 2010 05:37

•

Tags:

bay-ridge, bethlehem, brooklyn, crime-fiction, kentucky, library-journal, louisville, manhattan, matt-beynon-rees, middle-east, mystery-fiction, new-york, omar-yussef, palestinian, reviews, the-fourth-assassin, the-samaritan-s-secret, u-n

Back to diplomacy school for Israel

JERUSALEM, Israel — The American humorist Caskie Stinnett once wrote that “a diplomat is a person who can tell you to go to hell in such a way that you actually look forward to the trip.” In other words, someone who doesn’t make his meaning so clear that one is both afraid of the trip to hell and angry about being sent there.

JERUSALEM, Israel — The American humorist Caskie Stinnett once wrote that “a diplomat is a person who can tell you to go to hell in such a way that you actually look forward to the trip.” In other words, someone who doesn’t make his meaning so clear that one is both afraid of the trip to hell and angry about being sent there.Which makes Israel’s two top “diplomats” rather less than diplomatic.

Deputy Israeli Foreign Minister Danny Ayalon caused turmoil in relations with Turkey last week when he decided to upbraid the Turkish ambassador. Ayalon and his boss, Foreign Minister Avigdor Lieberman, wanted to let the Turks know that they found it unacceptable that a Turkish TV drama portrayed Israeli agents kidnapping children and the Israeli ambassador’s assassination.

Ayalon kept the Turkish ambassador hanging around in an anteroom, in front of cameras from two Israeli news channels. When he brought him and the cameras into his office, he sat the unfortunate envoy in a low sofa and perched stony-faced on his own, much higher chair. Between them on the coffee table stood a single Israeli flag about the size of a pocket handkerchief.

Then he turned to the cameras and said, in Hebrew: “Pay attention that he’s sitting in a low chair and we’re higher up, and there’s no Turkish flag here, and we’re not smiling.” The cameramen suggested a handshake. “No,” said Ayalon. “That’s the whole point.”

In the Oxford Dictionary I keep on my desk, “diplomacy” is described as “skill in managing international relations; adroitness in personal relationships, tact.” Perhaps Ayalon, who’s always been rather charming and intelligent when I’ve met him, ought to keep a copy on his desk. Maybe he put it in the drawer with the little Turkish flag he stands on the coffee table, when he isn’t trying to show the Turkish ambassador that he’s angry with him.

The following day, the Turkish ambassador spoke out in an interview with an Israeli newspaper. “How could he be so rude?” he said.

That was essentially the reaction in Israeli newspapers, whose journalists are no fans of Foreign Minister Lieberman, an indelicate former night-club bouncer whose burliness and Moldovan birth make him — in the eyes of the press — rather unqualified to tread the minefield of politesse that is international diplomacy.

Ayalon issued an equivocal apology after a day. But the Turks insisted on a fuller apology, which came after the Turkish president said Ankara might recall its ambassador.

“I wish to express my personal respect for you and the Turkish people,” Ayalon wrote to the Turkish ambassador, “and assure that although we have our differences of opinion on several issues, they should be discussed and solved only through open, reciprocal and respectful diplomatic channels.”

On the same day Ayalon told the Israeli parliament that because of his protest “Israel is respected more.” Presumably he means that the Turks will be satisfied with the apology but will tread more carefully in the future lest their representative find himself sinking into a low chair without a nice Turkish flag to cling onto.

Why do relations with Turkey matter so much to Israel, and why did things get so bad this week?

Turkey is a major client of Israel’s defense industries. Despite the diplo-spat, Defense Minister Ehud Barak is in Turkey for an official visit during which he’ll discuss some important new military contracts. Last month Turkey said it’d push ahead with a $190-million deal to buy drones from Israel Aerospace Industries.

Some Israeli commentators believe Lieberman and Ayalon, whose party Israel Our Home sits uncomfortably in the cabinet alongside Barak’s fractious Labor Party, engineered the tension to embarrass the defense minister.

More likely Lieberman had had enough with Turkish vilification of Israel. That began a year ago, when Turkey was one of the most outraged opponents of the war Israel waged on Hamas in the Gaza Strip. The reaction back then included a surprisingly undiplomatic outburst at the economic conference in Davos, when Turkish Prime Minister Recep Erdogan berated Israeli President Shimon Peres and stormed off the stage because the host told him it was time to end the panel and go to dinner.

Since then, Israeli diplomats maintain, Erdogan has missed no opportunity to lambast Israel. In Lebanon last week, Erdogan argued that Israel’s nuclear capability ought to be treated the same way as Iran’s nuclear program, and also said Israel threatens “world peace.”

The Israeli diplomats say the Turkish TV show was the last straw for Lieberman and provided a veiled way of punishing Erdogan for his aggressive statements.

In which case, it was actually quite diplomatic.

GlobalPost

Published on January 21, 2010 23:40

•

Tags:

avigdor-liebermann, danny-ayalon, dipolomacy, foreign-minister, foreign-relations, global-post, israel, journalism, middle-east, recep-erdogan, shimon-peres, turkey

Bringing the Mideast to America

Often a novelist can humanize foreign affairs in ways a journalist can't.

Often a novelist can humanize foreign affairs in ways a journalist can't.To mark publication today of my new Palestinian crime novel The Fourth Assassin, I posted this for my regular column on GlobalPost.

Though we do so at our peril, overseas events are convenient to ignore. We turn past the foreign pages of the newspaper. We might not even get a passport or voyage further than Florida for vacation.

But if we ignore the world beyond our borders, one day that world will come to remind us that it’s there. That’s what happened on 9/11 and in the terror attacks in Madrid and London.

Readers of GlobalPost by definition understand this — it’s why they’ve come to a site which now covers the globe as almost no other U.S. news organization does. Many readers, however, don’t know what important world news they’re missing.

That’s why I decided to bring my fictional Palestinian detective Omar Yussef to the U.S. in my new novel, which is set in Brooklyn. To remind American readers that the Muslim world exists, and that Westerners need to understand how Muslims think. The politics of the Muslim world isn’t just restricted to the Middle East and Asia; it’s in our own towns.

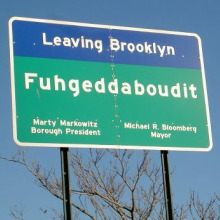

In “The Fourth Assassin,” Omar Yussef comes to New York for a U.N. conference. He visits the Bay Ridge neighborhood of Brooklyn, which these days is becoming known as “Little Palestine” because of the steady influx of immigrants from the West Bank.

Little Palestine isn’t a community of Palestinian intellectual emigres of the kind that emerged in most major Western capitals during the 1970s. It’s a new wave of mostly young men who come to drive taxis and work several jobs, until they can afford to bring their families over to join them. Theirs is the typical American immigrant story, in fact. Except for the FBI investigations.

After 9/11, the FBI cottoned to the fact that there were Palestinians in Bay Ridge. According to community leaders and Brooklyn media, agents went into Little Palestine, recruiting their own operatives and coming away with alleged links between prominent local Palestinians and violent groups back home, such as Hamas.

The Bureau didn’t uncover any broad conspiracy in Little Palestine. But its actions added to the tension between New Yorkers and local Arabs after the attack on the Twin Towers. That’s the situation into which I wanted to place Omar Yussef, a Muslim with an often unconventional political take. Mutual distrust makes for a good crime novel. It also happens to be real.

The conflict between the West and the Muslim world today is much like the Cold War of decades past. I’d wager that few people read the nonfiction written about the confrontation with the Soviet Union any more. But some of the best fiction about that time, say John Le Carre’s Smiley novels or books like Martin Cruz Smith’s “Gorky Park” which went deep into Russian society during those years, still speak to us even though that battle is long finished.

That’s because those books examine a time of conflict in a timeless way. By humanizing all the participants in the conflict, those novels go beyond nonfiction and give us a window into the minds of those people who’d otherwise seem to us inhuman enemies. I hope “The Fourth Assassin” does that, too.

When Omar arrives in Bay Ridge, he finds a headless body in his son’s bed. The gruesome discovery leads him to uncover a suicidal assassination plot that seems to involve some of his former pupils in his school in Bethlehem. One of the suspects: his own son.

Much of what goes on in the novel stays within the Palestinian community, most of which came from the village of Beit Hanina on the border between Jerusalem and Ramallah. These immigrants fled the violence of the intifada and, over the last decade, moved into a neighborhood that had traditionally been Norwegian and Irish.

These days Little Palestine is dotted with basement mosques, Arab restaurants and boutiques selling slinky headscarves for religious Muslim women who want to observe the signs of their faith while also highlighting their beauty.

But the novel also takes Omar to Atlantic Avenue and Coney Island — iconic areas of Brooklyn we might be more accustomed to seeing in traditional thrillers, though they now have strong Arab presences. I put those locations into my novel so that readers would understand that the politics of the Middle East can’t be isolated. You can take the N train from Times Square and get off in Palestine.

I hope “The Fourth Assassin” will help readers understand that.

Published on February 01, 2010 06:16

•

Tags:

matt-beynon-reees, middle-east, new-book, new-york, omar-yussef, palestine, publication-date, terrorism, the-fourth-assassin, ttle-palestine, twin-towers, united-nations

Palestine Scene of the Crime

Crime writer J. Sydney Jones has a new blog called Scene of the Crime. He aims to interview writers about the impact on their writing of the location and sense of place in their novels -- usually from far-flung countries. This week he features me on my Palestinian crime novels. Read on, for the full interview.

Crime writer J. Sydney Jones has a new blog called Scene of the Crime. He aims to interview writers about the impact on their writing of the location and sense of place in their novels -- usually from far-flung countries. This week he features me on my Palestinian crime novels. Read on, for the full interview.A Different View of Palestine

Matt Beynon Rees has staked out real estate in the Middle East for his acclaimed Crime Writers Association Dagger-winning series of crime novels featuring Palestinian sleuth Omar Yussef. The books have sold to publishers in 23 countries and earned him the title “the Dashiell Hammett of Palestine” (L’Express).

His newest, The Fourth Assassin, which is out on Feb. 1, finds Yussef in New York for a UN conference and visiting his son, Ala, who lives in Bay Ridge, a Brooklyn neighborhood with a large Palestinian community. Of course murder and mayhem greet Yussef in New York, just as in Palestine, and he is ultimately forced to investigate in order to clear his son of a murder charge.

Scene of the Crime caught up with Matt in New York, where he is promoting his new book. He was kind enough to take time away from his busy schedule to answer a few questions.

Describe your connection to Jerusalem and Palestine. How did you come to live there or become interested in it?

I arrived in Jerusalem for love. Then we divorced. But I stayed because I felt an instant liking for the openness of Palestinians (and Israelis). When I arrived I had just spent five years as a journalist covering Wall Street. Frankly that exposed me to a far more alien culture than I experienced when I became a foreign correspondent in the Middle East. People in the Middle East are always so eager to tell you how they FEEL; on Wall Street no one ever talked about feelings, just figures. Rotten material for a novel, figures are. I’ve lived now 14 years in Jerusalem.

What things about Palestine make it unique and a good physical setting in your books?

Palestine is a place we all THINK we know. It’s in the news every day. Yet the longer I’ve been there, the more I understand that the news shows us only the stereotypes of the place. Terrorism, refugees, the vague exoticism of the muezzin’s call to prayer. What better for a novelist than to take something with which people believe themselves to be familiar and to show them how little they really know. To turn their perceptions around. The advantage is that I begin from a point of some familiarity – it isn’t a completely alien location about which readers know nothing. Imagine if I’d set my novels in, say, Tunisia or Bahrain. Not far from where my novels take place, but much more explanation needed because they’re rather a blank. With Palestine, I’m able to manipulate and disturb the existing knowledge of the place we all have.

Did you consciously set out to use Palestine as a “character” in your books, or did this grow naturally out of the initial story or stories?

I arrived in Jerusalem as a journalist, but I’ve felt that I’m on a vacation every day of those 14 years I’ve lived there. Every minute I spend in a Palestinian town or village, my creative senses are heightened, to the point where it becomes quite exhausting. Part of that is because of the people, the way they speak and feel. But most of it is the experience of place. The light so bright off the limestone. The smells of spices and shit in the markets. The cigarette smoke and damp in the covered alleys. It’s important to note that each Palestinian town is extremely distinctive – which might not be evident from the news. My first novel takes place in the historic town of Bethlehem. The second is in Gaza, which seems like another world. Nablus, where the third book is set is an ancient Roman town, built over by the Turks. …My new novel sees my Palestinian detective Omar Yussef come to Brooklyn. I move him around BECAUSE place is the driver of the novels. The main characters are the same; but I draw something different out of each of them by shifting them to new places.

How do you incorporate location in your fiction? Do you pay overt attention to it in certain scenes, or is it a background inspiration for you?

The texture of a Palestinian town is so rich, it ends up defining the atmosphere of the novel. With the casbah of Nablus for example: I was stuck in its old alleys during the intifada with gunfire all around, not knowing who or what might be round the next corner, and it seemed so sinister and beautiful at the same time. The locations are more than background. They’re significant because I write about Palestinian culture and society and people, in the context of a mystery. You couldn’t take my mysteries and change the names and put the Golden Gate in the background and say they were set in San Francisco. They’re the books they are because Palestine is as it is.

How does Omar Yussef interact with his surroundings? And conversely, how does the setting affect him?

Omar Yussef, my detective, is based on a friend of mine who lives in Dehaisha Refugee Camp in Bethlehem. It’s important to me that he should be a Muslim, someone who loves his traditional family life and tribe, someone who belongs very deeply to Bethlehem. That’s because I’m trying to show readers what they’re missing when they see the Palestinians only as stereotypical terrorists or victims. His reaction to the chaos around him is that of an honorable man who finally is driven to stand up against the negative forces at work in his town.

Has there been any local reaction to your works? What do local Palestinian and Israeli reviewers think, for example. Are your books in translation in Palestine, and if so, what reaction have they gotten from reviewers?

Hanan Ashrawi, a former Palestinian peace negotiator and a leading political figure, said of The Collaborator of Bethlehem that “it reflects the reality of life in Bethlehem– unfortunately.” (After all, it’s a crime novel of exceeding chaos.) I get a lot of emails from Arabs noting that I’m showing the reality of their people in a way that isn’t reflected in Arab media – which just blames Israel for everything – or in Western media, where the Palestinians are usually just stereotypes set in opposition to Israel. Translation into Arabic is a slow business – Henning Mankell sold 40 million books before he got an Arab translation last year – but I’m hopeful. Meanwhile the first book was translated into Hebrew and got good reviews. Israelis were very glad to have an opportunity to learn about life beyond the wall that they’ve built between Jerusalem and Bethlehem.

Of the novels you have written set in Palestine, do you have a favorite book or scene that focuses on the place? Could you quote a short passage or give an example of how the location figures in your novels?

In my third novel. The Samaritan’s Secret, there’s a scene in an old palace in the Nablus casbah called the Touqan Palace. This was the real palace I discovered on my first visit to the West Bank (to cover the funeral of a man who’d been tortured to death in the local jail). I finished my reporting and went for a walk about the casbah. I’d heard about the Touqan Palace and a friendly Palestinian helped me find it. We shouldered open the door, climbed through the goat pen inside, and came into a courtyard strung with cheap laundry and with chickens living in the ornate fountain at the center. The wealthy family that built the palace had moved to a new place up the hillside; now the palace was home to poor refugees. It struck me very powerfully as a political irony. But I also loved the stink of the chickens and the way the goats nuzzled at me and the children who lived there came through the dust to chat with me. I tried to get that feeling of a people estranged from their history into the novels through Omar Yussef, who’s a sleuth but also a history teacher. So the scenes in the Touqan Palace are quite pivotal, thematically, for me.

Who are your favorite writers, and do you feel that other writers influenced you in your use of the spirit of place in your novels?

I love Paul Bowles (The Sheltering Sky, Let it Come Down). He used to travel the Arab world and, each day, would incorporate into his writing something that had happened the previous day as he journeyed. That’s a technique I’ve used. It makes you look sharply at the emotions you experience when you’re in a strange place. In some ways it was most useful when I wrote The Fourth Assassin, which is set in Brooklyn. I know New York very well but I made a great effort to see the place as a new immigrant or a total foreigner might. I discovered that it was daunting and oppressive and crowded and huge and threatening and cold as hell – it actually made me a little depressed. Which was the point of doing my research that way. I think of it as method acting for writers.

Visit Matt at his homepage, and also on his blog. Thanks for the insightful comments, Matt, and good luck with the new book.

Published on February 02, 2010 07:09

•

Tags:

bethlehem, brooklyn, crime-fiction, exotic-fiction, gaza, golden-gate, interviews, israel, j-sydney-jones, jerusalem, matt-beynon-rees, middle-east, nablus, new-york, omar-yussef, palestine, palestinians, san-francisco, the-fourth-assassin, writing

Wall St Journal on 'The Fourth Assassin'

While in New York this last couple of weeks, I stopped into the space-age HQ of Rupert Murdoch's News Corp on the Avenue of the Americas in Midtown Manhattan. Once my eyes had adjusted to the superbright white light everywhere, I settled into a studio for an interview with Jon Friedman (the man known around NY as "Mister Media") to talk about how I researched my new novel THE FOURTH ASSASSIN.

Published on February 09, 2010 05:24

•

Tags:

book-research, brooklyn, jon-friedman, marketwatch, matt-beynon-rees, middle-east, new-york, omar-yussef, the-fourth-assassin, the-wall-street-journal, travel, video, writing

Jerusalem Zoo: Penguins before pols

Here's a whimsical video explaining why the Jerusalem Biblical Zoo is the best vantage point from which to observe the Palestinian-Israeli conflict -- superior even than a Gaza refugee camp or an Israeli military base. Seriously. And yet not.

Published on February 11, 2010 00:55

•

Tags:

animals, arabs, crime-fiction, fish, global-post, israel, israeli-palestinian-conflict, jerusalem, jerusalem-biblical-zoo, journalism, leopards, lions, matt-beynon-rees, middle-east, palestine, penguins, politicians, politics, sara-sorcher, terrorism, tigers, ultra-orthodox-jews, video

Why's a Palestinian sleuth in Brooklyn?

I’ve been called the Dashiell Hammett of Palestine, the John Le Carre of the Middle East, the James Ellroy of…Palestine, the Graham Greene of Jerusalem, and the Georges Simenon of the Palestinian refugee camps. Depends which review you happen to have read.

I’ve been called the Dashiell Hammett of Palestine, the John Le Carre of the Middle East, the James Ellroy of…Palestine, the Graham Greene of Jerusalem, and the Georges Simenon of the Palestinian refugee camps. Depends which review you happen to have read.Until now I’ve published three novels about Omar Yussef, my Palestinian schoolteacher/sleuth. Omar has been described as the Philip Marlowe of the Arab street, the Hercules Poirot of the Near East, Sam Spade fed on hummus, and Miss Marple crossed with Yasser Arafat.

Why then is my new Omar Yussef novel THE FOURTH ASSASSIN,/a> set in New York City? Not in the Middle East, the Near East, Palestine, the Levant, the Fertile Crescent, or any other place where Yasser may be fornicating with dear old Miss Jane Marple.

I lived in New York six years, until I came to Jerusalem in 1996. I know it better than any city outside the Middle East. I had a lot of fun in New York. Maybe too much fun. In no other place in the world can a young man so overindulge in the temptations originally offered in the city of Sodom. Which in reality is close to where I live now in Jerusalem. Though you wouldn’t know it to look at the place.

I know New York with my eyes closed. Literally. In my twenties, after leaving some bar or club, I blacked out on every line on the subway map.

I dated women from every borough of the city, from Westchester and upstate. From the 201 area code (dare I say, New Jersey.)

I married a girl from the North Shore of Long Island, and in my continuing effort to know New York in all its facets, when we divorced, I married a beautiful woman from the South Shore of Long Island.

But each time I returned, no matter how well I thought I knew the place, New York seemed different. The change became most apparent after 9/11. I wanted to understand it through the eyes of Omar Yussef.

That’s why he finds himself in Brooklyn in THE FOURTH ASSASSIN. Visiting the area of Bay Ridge that has become known as “Little Palestine,” for the influx of Palestinian immigrants.

Little Palestine isn’t a community of Palestinian intellectual émigrés, such as sprang up in European capitals in the 1970s. It’s a new wave of young men mostly, saving to bring their families over, working two or more jobs. Theirs is a typical American immigrant story.

Except for the FBI agents going through their trash.

The Bureau didn’t uncover any broad conspiracy in Little Palestine. But it did add to the tensions between the Arab community and other New Yorkers after the attack on the Twin Towers.

That’s the situation into which I wanted to place Omar Yussef. Mutual distrust, after all, makes for good crime fiction.

In Brooklyn, it also happens to be real.

Published on February 11, 2010 23:51

•

Tags:

bay-ridge, brooklyn, crime-fiction, dashiell-hammett, fbi, fertile-crescent, georges-simenon, graham-greene, hercules-poirot, james-ellroy, jerusalem, levant, little-palestine, long-island, middle-east, miss-jane-marple, miss-marple, near-east, new-jersey, new-york, omar-yussef, palestine, palestinians, philip-marlowe, sam-spade, the-fourth-assassin, upstate-new-york, westchester-county, yasser-arafat

Espionage is a dirty business

You’d think there was something wrong with spying.

You’d think there was something wrong with spying.People pay rather a lot of money to watch Daniel Craig dispose of villains in the bloodiest fashion. They nod in approval when M pushes 007’s perfect false passport across the desk. Yet everyone seems to be peeved about what in all likelihood is a Mossad hit against a Hamas operative in his Dubai hotel room on January 20.

Oh, that’s right, because the Hamas guy – meanies though Hamas might be – was a real human being who’s now dead, after all.

No, wait, that isn’t it. Western governments don’t really care about dead Arabs. If they did, they wouldn’t have sent Tony Blair to be the Middle East peace-process point man for the Quartet (the UN, the US, the EU and Russia), even though it ought to be perfectly clear that the only person disliked more in the Arab world than the stammering King of Cool Britannia is the future head librarian of the Presidential Library in Crawford, Texas. (Why so unpopular? Started a war that killed a lot of Iraqis, that’s why. Arabs do care about dead Arabs…sometimes.) So it isn’t the dead guy that’s behind the international fuss.

Ah, that’s right. These spies used our passports. Of the 11 assassins identified by Dubai’s police chief this week, all were carrying British, Irish, German or French passports. Three of the British passports carried the near-perfectly correct details of three Brits who’ve also taken up Israeli citizenship. Three others included names similar to European-Israeli citizens, though other details were incorrect.

To a crime novelist, the passport thing seems pretty tame. I suspect that, actually, the Euro pols and dips would like to lambaste Israel for the hit itself. They can’t quite bring themselves to do it, because, after all, Islamic extremism is the West’s current Enemy Number One. And whatever you think of Hamas, they’re into Islam and they’re pretty extreme. So the passport shenanigans get to be the focus of Euro ire.

I can understand why European governments will feel the need to throw a diplomatic hissy fit. But they’re wasting their time on the Israelis. In Israel you can throw a real, full-on hissy fit in public at some outrageous slight, and your Israeli target will simply go blank-faced and turn away, as though you’re the one who’s gone too far. The diplomatic version is laughably unsuited to the Middle East.

In other words, diplomacy in this region is pointless. You want someone to get a message, you kill.

If that sounds like the world of crime fiction, then that’s why this neighborhood is so well-suited to the genre. That’s why my Palestinian crime novels are a better way to understand the reality of this place than the international pages of your newspaper (which, you can be sure, will be running stories in which diplomatic protests by Whitehall and the Quai d’Orsay are taken seriously, rather than being treated as the piffling waste of time that they truly are.) Don’t take them seriously. Get yourself a novel instead.

(I posted this on the International Crime Authors Reality Check blog).

Published on February 18, 2010 22:46

•

Tags:

007, assassin, crime-fiction, daniel-craig, dubai, espionage, hamas, hitman, james-bond, middle-east, mossad, palestine, palestinian, spying, tony-blair