Matt Rees's Blog - Posts Tagged "damascus"

The Writing Life interview: Alon Hilu

The most original voice in Hebrew fiction is that of Alon Hilu. His first novel “Death of a Monk” took a blood libel against the Jews of Damascus in 1840 and offered a startling alternative perspective on how the murder at the heart of the scandal might have taken place. The second of his novels “House of Dajani” will be out in English next year, but it’s already controversial in Israel. Set in 1895 it casts a different light on the early Zionist settlers of what was then Palestine, suggesting that the precursors of today’s Israelis might not have been quite so heroic. “Dajani” is set in Jaffa, where Alon was born in 1972. His parents were born in Damascus.

How long did it take you to get published?

I was first published at the age of 20 (two short stories were published in Israeli literary magazines), and my first novel, “Death of a Monk” was published when I was 32.

Would you recommend any books on writing?

“The Art of Dramatic Writing” by Lajos Egri – written originally for playwrights – gives the basics for writing, and I found it very useful. The most challenging part for me in writing is the structuring of plots, and for this particular purpose I use the book “20 Master Plots (and how to build them)” by Ronald B. Tobias, which I highly recommend.

What’s a typical writing day?

My writing discipline is very poor. I only write when I feel I want to write. It usually happens during the quiet hours of late night.

Plug your latest book. What’s it about? Why’s it so great?

“The House of Dajani” is a gothic story about a Palestinian child who lives in Jaffa in 1895, and can see the far future, and in particular the Jewish-Arab conflict and the many wars to come. He meets a 27 year old Zionist immigrant, and their relationship begins with love, but transfers into hate, when the child accuses the Jewish adult of killing his father. The book can be read as a metaphor of the Jewish-Arab relationship in Israel during the last century, became a best seller in Israel and is being translated into five languages. I love this book because it takes the readers back to late 19th century, and describes the landscape and people of what I call “Palestinian Tel Aviv”.

How much of what you do is dictated by formula – how much is complete originality?

I always work with the same formula of plot structure, which is comprised of a triggering event, a developing conflict, a crisis and a resolution. I write the synopsis in advance and remain pretty close to it. What changes from book to book is the content poured into the structure.

What’s your favorite sentence in all literature, and why?

The first sentence of “Lolita” by Vladimir Nabokov: “Lolita, light of my life, fire of my loins. My sin, my soul. Lo-lee-ta: the tip of the tongue taking a trip of three steps down the palate to tap, at three, on the teeth. Lo. Lee. Ta”. It is poetically written, and absorbs the obsession of the narrator in few words. I also love the novel – it is undoubtedly a masterpiece.

How much research is involved in each of your books?

My first two books were historical novels, and naturally I had to invest time and energy to research the historical period and place (1840 Damascus in “Death of a Monk” and 1895 Jaffa in “The House of Dajani”). It takes me about one to two years to complete the research.

Where’d you get the idea for your main character?

From the research. I intentionally look for the forgotten characters, which are not praised by historians, and I usually have only one descriptive sentence about the character when choosing him. In my first book, the protagonist was Aslan Farhi, a 19 year old Jew from Damascus, who accused his father of killing a monk for ritual purposes. The descriptive sentence I had in mind was: “the son who falsely accused his father”. In the second novel, the main character is a 12 year old Palestinian child who foresee Zionism and the establishment of the state of Israel. The descriptive sentence of him was: “the child who could see the death of his people”.

What’s your experience with being translated?

Each of my books has been translated into five languages. Since I write in anachronistic Hebrew, it is always a challenge for my translators to depict the aroma of the Hebrew to the target language. Of my translated books, I can only read English, and I can tell that my translator, Evan Fallenberg made a terrific work in translating both books. [I interviewed Evan Fallenberg recently in The Writing Life series.--MBR]

Do you live entirely off your writing? How many books did you write before could make a living at it?

No, I work as a general counsel of a hi-tech company called Voltaire Ltd. and I make my living off being a lawyer.

How many books did you write before you were published?

One – the one that was published (“Death of a Monk”).

What’s the strangest thing that happened to you on a book tour?

I went to downtown San Francisco to lecture at the LGBT center, and found out that the entrance was blocked by angry women. It was a contest against my lecture, held by an anti-Israeli Lesbian group based in California. They proclaimed that the LGBT should not host events sponsored by the Israeli consulate, because Israel was anti-gay (which is a ridiculous argument anyway).

What’s your weirdest idea for a book you’ll never get to publish?

No such thing – everything is worth to print.

Cheers for Hitler, and Brits go home

The company you keep can put the culture around you in a new light, let you see it as you haven’t before.

The company you keep can put the culture around you in a new light, let you see it as you haven’t before.That’s true when I travel to different countries and discover that readers in Germany have a particular take on my Palestinian crime novels which differs from the way they look to Americans, for example.

I got to thinking about this when I was wandering the Nablus casbah this week with two German friends. An enthusiastic Palestinian fellow asked me to explain to them how much he appreciated Hitler, and as an afterthought he noted that all his people’s problems are caused by me and my compatriots from the British Isles.

I had just climbed up the old Turkish clocktower in Manara Square at the heart of the casbah with one of the Germans. I’d never seen the door at the bottom open before, but there was a policeman inside on this occasion and he generously allowed us to go up the ladder. On the first balcony, I stepped through more pigeon feces than I’d have thought could possibly gather in one place. It was crusty for an inch or two, then a little slushy beneath. I had a grin all over my face of the kind that tends to appear there when I discover a new corner in a place I’ve often been – and loved being there – before.

Read the rest of this post on my blog The Man of Twists and Turns.

Published on June 17, 2010 01:33

•

Tags:

barry-unsworth, bedouin, berlin, crime-fiction, damascus, dehaisha-refugee-camp, george-w-bush, germany, hamas, hitler, imperial-camel-corps, jerusalem, middle-east, nablus, omar-yussef, ottomans, palestine, palestinians, the-rage-of-the-vulture, the-samaritan-s-secret, tony-blair, turkey, wales

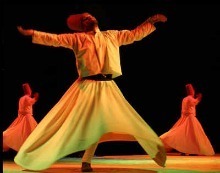

FREE Omar Yussef short story: Damascus Trance

I've written this story as an immediate response to the murder and arrest of anti-government demonstrators all over Syria--and elsewhere in the Arab world. It’s a work of fiction based on the characters in my series of Palestinian crime novels. But real people are still being killed.

I've written this story as an immediate response to the murder and arrest of anti-government demonstrators all over Syria--and elsewhere in the Arab world. It’s a work of fiction based on the characters in my series of Palestinian crime novels. But real people are still being killed.DAMASCUS TRANCE

An Omar Yussef story

By Matt Rees

The crowd started to clear the wide, covered arcade of the Souk Hammidiyye even before the first shot. Omar Yussef saw a dread deeper than mere terror on the faces of the people hurrying out of the Ottoman market and into the alleys around the Ummayyad Mosque. They look disgusted with themselves, he thought. They had started to believe they had the courage to walk toward trouble, not to flee from it.

Three reports from a rifle out beyond the old Hejaz Railway Station and a rustle of distant outrage, as if the crowd were an old man bothered by his grandchildren during a nap.

“It’s going down.” Khamis Zeydan caught Omar Yussef’s elbow and pulled him out of the sudden stream of the crowd. They sheltered on the step of a store that sold seeds and roots which promised to make a man potent.

“All these years it was we Palestinians who did the rioting,” Omar Yussef said. “Our first day in Damascus and it’s happening here."

A shot, this time closer, from al-Thawra Street, and one of the yellowed glass panes in the vaulted roof of the arcade shattered. Every face was stern and still, but someone must have been shouting because it seemed the crowd was born aloft and accelerated on a tide of noise.

The storekeeper reached for his shutter with a long hook. “I have to close, ustaz.” Omar Yussef moved off the step and the metal rolled down. He glanced at the merchant. He was about Omar Yussef’s age, nearing sixty, and something about his high cheekbones was familiar despite his frothy white beard. As the storekeeper knelt to snap the padlock, the edge of the crowd jostled him, and as soon as the key was out he was on his feet and swept away.

A whirlpool of panic broke around Omar Yussef and Khamis Zeydan, pressing them between the chests and backs and shoulders of the men around them so that their feet barely connected with the ground. They slipped powerless from one set of bodies to another, exchanging the scents of different sweats and wondering at the pointless projection of angry voices like dogs joining a starlight chorus.

When the crowd spat them out into an alley, Khamis Zeydan lit a Rothman’s. “I haven’t run that far since we were in University.”

“Let’s hope it’s the only part of our student life that’s repeated at this reunion,” Omar Yussef said. “You know how I was back then.”

Read the rest of this story on my blog The Man of Twists and Turns.

Published on May 12, 2011 07:01

•

Tags:

anti-government-demonstrations, arab-awakening, arab-democracy, arab-spring, crime-fiction, damascus, damascus-trance, free-story, middle-east, mystery-story, omar-yussef, palestine, palestinians, pro-democracy-demonstrations, short-story, syria