Matt Rees's Blog - Posts Tagged "nablus"

Armchair travel: reviews from Philly Inky, Eurocrime, JC, Books for Free

My new Palestinian crime novel THE SAMARITAN’S SECRET gets great reviews this week on both sides of the Atlantic – and in the blogosphere, wherever that is.

On the “This Book for Free” blog, Shoshana writes that THE SAMARITAN’S SECRET “has taken me into a part of the world I wouldn’t have known at all. I have no idea that there are actual Samaritans left in these world. This book was an eye-opener for me. I know about the “Good Samaritan” from the bible. But like other things biblical, I thought they don’t exist anymore. Well, this book took me on a field trip in this part of the world. The mystery is a bonus for me. But what really got me into this book is the way it takes me on a tour in Nablus. I believe I can almost smell the place and taste the food. This book is one of the best armchair traveling tools I have encountered.”

In world of “old media” Philiadelphia Inquirer reviewer Peter Rozovsky (who blogs about international detective fiction) picks up on the way my novel handles the very current battle between Hamas and Fatah, the two main Palestinian factions: “Partisans of Fatah, which Arafat headed, might squirm at a plot set in motion by Arafat's massive financial corruption. Their Hamas counterparts are no more likely to enjoy depictions of a fanatical sheikh - or the glimpses of Hamas green as thugs beat up Yussef. But Rees is interested less in Fatah and Hamas than in the tortured history of the Palestinian people. ‘No one knew who would be alive the next day,’ a character tells Yussef. ‘You could be killed by the Syrians, the Israelis, the Christian militias, the Shiite gangs, by one of the other Palestinian factions, or even by the Old Man himself.’

In Eurocrime, Laura Root writes that: “THE SAMARITAN'S SECRET provides a sensitive and fascinating portrait of Palestinian life and culture, both at grassroots and the political level, imaginatively evoking the smells, food and customs of the casbah, cafes and bathhouses….THE SAMARITAN'S SECRET is an intriguing, complex thriller giving a compelling insight into the politics, culture and day to day family life in this Palestinian city.”

The UK’s Jewish Chronicle runs a review under the headline “Shlumpy sleuth lifts the lid on Palestine” which includes: “The Samaritan’s Secret is not as bloody or with as high a body count as Rees’s previous two books, but, like them, it provides a really fascinating inside view of Palestinian society. Not least, post-Gaza, is Rees’s skilful delineation of the war between Fatah and Hamas, here fighting over an expected tranche of funds from the World Bank. Hamas’s attempt to show that “the Old Man” — Arafat — died of Aids is cleverly deployed by Rees as a shameful propaganda weapon with which to attack Fatah. The exposure of further dark secrets, including that of the eponymous Samaritan, cast a useful light on quite how Hamas maintains its grip on the Palestinian street…Rees’s novels should be required reading for anyone seeking to understand the Palestinian mind-set.”

On the “This Book for Free” blog, Shoshana writes that THE SAMARITAN’S SECRET “has taken me into a part of the world I wouldn’t have known at all. I have no idea that there are actual Samaritans left in these world. This book was an eye-opener for me. I know about the “Good Samaritan” from the bible. But like other things biblical, I thought they don’t exist anymore. Well, this book took me on a field trip in this part of the world. The mystery is a bonus for me. But what really got me into this book is the way it takes me on a tour in Nablus. I believe I can almost smell the place and taste the food. This book is one of the best armchair traveling tools I have encountered.”

In world of “old media” Philiadelphia Inquirer reviewer Peter Rozovsky (who blogs about international detective fiction) picks up on the way my novel handles the very current battle between Hamas and Fatah, the two main Palestinian factions: “Partisans of Fatah, which Arafat headed, might squirm at a plot set in motion by Arafat's massive financial corruption. Their Hamas counterparts are no more likely to enjoy depictions of a fanatical sheikh - or the glimpses of Hamas green as thugs beat up Yussef. But Rees is interested less in Fatah and Hamas than in the tortured history of the Palestinian people. ‘No one knew who would be alive the next day,’ a character tells Yussef. ‘You could be killed by the Syrians, the Israelis, the Christian militias, the Shiite gangs, by one of the other Palestinian factions, or even by the Old Man himself.’

In Eurocrime, Laura Root writes that: “THE SAMARITAN'S SECRET provides a sensitive and fascinating portrait of Palestinian life and culture, both at grassroots and the political level, imaginatively evoking the smells, food and customs of the casbah, cafes and bathhouses….THE SAMARITAN'S SECRET is an intriguing, complex thriller giving a compelling insight into the politics, culture and day to day family life in this Palestinian city.”

The UK’s Jewish Chronicle runs a review under the headline “Shlumpy sleuth lifts the lid on Palestine” which includes: “The Samaritan’s Secret is not as bloody or with as high a body count as Rees’s previous two books, but, like them, it provides a really fascinating inside view of Palestinian society. Not least, post-Gaza, is Rees’s skilful delineation of the war between Fatah and Hamas, here fighting over an expected tranche of funds from the World Bank. Hamas’s attempt to show that “the Old Man” — Arafat — died of Aids is cleverly deployed by Rees as a shameful propaganda weapon with which to attack Fatah. The exposure of further dark secrets, including that of the eponymous Samaritan, cast a useful light on quite how Hamas maintains its grip on the Palestinian street…Rees’s novels should be required reading for anyone seeking to understand the Palestinian mind-set.”

Baksheeshed to the Bone

I'm guest-blogger today on Checkpoint Jerusalem, the excellent and delightfully varied blog by McClatchy Newspapers Middle East correspondent Dion Nissenbaum. Dion does a better job of rooting out interesting cultural angles on the news than anyone else covering the Middle East. Under the headline "Jesus was Right: Finding a Good Samaritan", Dion introduces my series of Palestinian crime novels and then posts this contribution from me:

It turns out Jesus was right.

I know, because I found a Good Samaritan.

Really, he was a good guy, and he actually was a Samaritan. There are still a few of them about.

In January, my new Palestinian crime novel, The Samaritan's Secret, was about to be published.

The story unfolds on a West Bank hilltop where the last remnants of the ancient Samaritan tribe live.

There are just 370 of them, high above the violent city of Nablus, near the site where they believe their ancient Temple stood.

To help my readers get a sense of the place, I decided to film a video clip using many of the locations from the book.

My friend, videographer David Blumenfeld. and I headed from our homes in Jerusalem to shoot the video.

The day before, I had spoken with a Samaritan priest to arrange some meetings and to be sure the enclosure around the Temple wouldn’t be locked.

“That depends on the money,” he said, in Hebrew. (The Samaritans mainly speak Arabic, but they also have Israeli ID cards and speak Hebrew. On their Sabbath, they speak nothing but Samaritan, which they believe is true ancient Hebrew.)

As a journalist, I’m not accustomed to paying to interview people.

“How much?” I asked.

“How much do you think?” he ventured.

Oh, no, we’re about to get all Middle Eastern, I thought. I hate haggling.

“Well, let’s say 200 shekels.” That’s about 60 bucks.

He scoffed.

“A thousand.”

I made groaning noises to show that such a figure was painful to me.

“Five hundred.”

“Five hundred,” he said. “See you tomorrow.”

When we reached the village, Kiryat Luza, the day was clear and sunny. The priest met us at the museum -- which he set up some years ago in his living room -- and we filmed a few scenes alongside his trove of photos and old documents.

Before we’d finished, he took out a receipt book: “I’ll do your receipt, shall I? What did we say? A thousand, wasn’t it?”

“No, it was five hundred.”

He started to tell me about how much work we were making him do. I gave him seven hundred and let it go.

Now, the priest was supposed to open the gates to the Temple compound for us. But somehow, after I’d paid him, that duty was delegated to another fellow.

As we filmed, the new guy complained that he needed to go home and eat. (The Samaritan village is about the sleepiest place I’ve ever seen. If anybody up there had anything pressing to do that necessitated hurrying me along, I’d have been very, very surprised.)

So, as we left, I gave him 100 shekels [about $25 US:] and thanked him with my warmest collection of Arabic words of praise.

“Something for the other guy?” he said, pointing at a figure lurking near the gate. “He had to wait too.”

I peeled off 20 shekels more. I hadn’t been squeezed this badly since I was first in the Middle East as an innocent 19-year-old backpacker, shucked for “baksheesh” by every Egyptian within a mile of the Great Pyramid.

David and I had filmed for four hours in a ridiculously hot January sun. I had read my cue-cards in five different languages, and I’d been fleeced until the leather on my wallet started to look raw. Sustenance was in order.

We went down the slope to the village to look for food.

There are only two establishments in the Samaritan village that in any way resemble eateries. “The Good Samaritan Restaurant” would’ve been the best bet, you’d have thought. But it serves no food -- only whiskey.

Next door, the “Guests and Tourists Paradise” was open. Three men smoked cigarettes lazily at one of the tables.

“Is it possible to eat?” I asked.

A tall, thin young man rose and welcomed us. We took a couple of Cokes from the fridge and sat. There was much muttering among the three smokers. Two of them disappeared up the street.

“I think they’ve gone home to ask Mamma to make our lunch,” I said to David.

Certainly no cooking took place in the kitchen at the back of the restaurant. The tall man smiled and nodded.

“No problem,” he said. “Food is coming.”

We waited... and waited... for half an hour. But the food did come, and it was good.

As we left, the young man told me his name was Samih. His father was the High Priest of the Samaritans. He gave me a free poster with historical information about the Samaritans and smiled very broadly.

Then he counted out my exact change.

I left a nice tip.

Published on April 28, 2009 05:58

•

Tags:

arab, arabic, east, good, hebrew, jesus, jew, mcclatchy, middle, nablus, newspapers, palestine, palestinians, samaritan, samaritans

May Allah bless such reviewers

America, the National Catholic weekly, includes a great review of The Samaritan's Secret, the third of my Palestinian crime novels, this week. "Rees masterfully concocts another claustrophobic tale from the occupied territories that takes us deep into the Palestinian experience even as it entertains," writes Claire Schaeffer-Duffy. She also calls my detective Omar Yussef "endearingly cranky." God bless him.

May Allah's blessings also fall upon the reviewer in Denmark's Information, who writes of the second of my novels "A Grave in Gaza" (UK title: The Saladin Murders): “Matt Rees who has run Time Magazine’s office in Jerusalem has traveled and lived amongst Palestinians and Israelis for years, and he knows what he’s talking about. This is why his new crime novel is both tremendous and terrible. It not cheerful, in fact it’s rather tragic, but Omar Yussef is a warm, jolly and lively acquaintance and the novel is certainly worth a read to find out what goes on behind the scenes in the Palestinian territories.“

Just to show that I prefer not to leave my books entirely in the hands of even the best of reviewers, the Media Line's Jerusalem bureau interviewed me for US radio stations a couple of days ago. Here I talk about my books and how I came to write them.

May Allah's blessings also fall upon the reviewer in Denmark's Information, who writes of the second of my novels "A Grave in Gaza" (UK title: The Saladin Murders): “Matt Rees who has run Time Magazine’s office in Jerusalem has traveled and lived amongst Palestinians and Israelis for years, and he knows what he’s talking about. This is why his new crime novel is both tremendous and terrible. It not cheerful, in fact it’s rather tragic, but Omar Yussef is a warm, jolly and lively acquaintance and the novel is certainly worth a read to find out what goes on behind the scenes in the Palestinian territories.“

Just to show that I prefer not to leave my books entirely in the hands of even the best of reviewers, the Media Line's Jerusalem bureau interviewed me for US radio stations a couple of days ago. Here I talk about my books and how I came to write them.

Can't wait for The Corruptionist

I heard from my chum Christopher G. Moore that he just finished writing the 11th in his series of Vincent Calvino crime novels set in Bangkok. That's good news, because I already read his brilliant and forthcoming Paying Back Jack. (See my review "Elmore Leonard in Bangkok"). Knowing Chris's work, I already love The Corruptionist -- I'm enjoying guessing how he'll use that terrific title and his vibrant cast of characters to take us on another superbly original dive into the underworld of Bangkok.

On his blog, Chris recently wrote about my latest Palestinian crime novel, The Samaritan's Secret. I'm delighted he enjoyed it -- not only because I'm such an admirer of his writing, but also because we share a birthday/a UK publisher/a style of examining the foreign culture in which we live through gritty crime fiction which exposes something you'd never expect about the place. Here's what he wrote:

"Matt Beynon Rees is another author who knows the territory, the people, and the nature of the personal conflicts that separate them. Matt’s turf is Palestine, and his novels are brim with people caught in the vice of poverty, tribal and clan conflict, and facing the constant possibility of violence. He brings Palestine to life. And that is no easy thing.

"One of Matt’s Omar Yussef mysteries does more to take a person into the day-to-day reality of the lives of people in Gaza than a library of newspaper and magazine analysis of Middle East politics. Ultimately understanding countries like the Palestine and North Korea are tied to their history, language, enemies, and traditions. The reality of such a country becomes understandable through emotional lens of the people who live there. Matt channels the sensibility of Graham Greene in this series, building a picture of a time and place that stays with you long after you finish the book."

So while you're waiting for The Corruptionist, get stuck into the first 10 Calvino novels. You won't be disappointed.

Published on June 07, 2009 07:21

•

Tags:

asian, bangkok, calvino, christopher, corruptionist, crime, g, jesus, moore, nablus, omar, palestine, samaritan-s, samaritans, secret, thailand, vincent, yussef

Dessert wars in the West Bank

It isn't only McDonald's that offers to supersize its food. In the most violent town in the West Bank, the local specialty is a hot cheese and syrup dessert called qanafi. Last month a Nablus baker made a qanafi that weighed 1,300 kg (1.3 tonnes). After the townspeople recovered from the sugar rush, a real estate developer put together a team this weekend to make a 1,700 kg qanafi that was 74 yards long.

The intention is to repair the image of a city damaged by nine years as the most dangerous place in one of the most dangerous regions of the world--by making enormous amounts of the thing Nablus would rather be famous for. The Palestinian Authority and Israel recently agreed to loosen military restrictions on the city a little. Of course, if you ate a few meters of the record-breaking qanafi (Guiness affirmation is awaited) it'd probably kill you -- but slower than a gunbattle. And what a way to go....

My favorite spot for qanafi is on the edge of the old casbah. It's called Aksa Sweets and it's always full of local men eating six-inch-square slices of the hot dessert. Qanafi's made with a base of elastic goats' cheese topped by a layer of noodles that look like shredded wheat, all drowned in a syrup so vibrantly orange that even Andy Warhol would have thought it in poor taste. The qanafi sits on wide circular metal trays, heated by a gas burner the size of an oil drum. Those who don't sit down take a big slice and eat it like Americans eat pizza, lifting it and seeming to pour it down their throats as they walk.

Part of the plot of my third Palestinian crime novel THE SAMARITAN'S SECRET revolved around my hero's attempts to defy the violence of the casbah to take his granddaughter for a slice of qanafi at a place based on Aksa Sweets. People eat qanafi all over the Arab world, but Nablus is where it was first made and the particular mix of goats' cheeses used here guarantees that it's the best place to eat it.

Here's how it's made:

The intention is to repair the image of a city damaged by nine years as the most dangerous place in one of the most dangerous regions of the world--by making enormous amounts of the thing Nablus would rather be famous for. The Palestinian Authority and Israel recently agreed to loosen military restrictions on the city a little. Of course, if you ate a few meters of the record-breaking qanafi (Guiness affirmation is awaited) it'd probably kill you -- but slower than a gunbattle. And what a way to go....

My favorite spot for qanafi is on the edge of the old casbah. It's called Aksa Sweets and it's always full of local men eating six-inch-square slices of the hot dessert. Qanafi's made with a base of elastic goats' cheese topped by a layer of noodles that look like shredded wheat, all drowned in a syrup so vibrantly orange that even Andy Warhol would have thought it in poor taste. The qanafi sits on wide circular metal trays, heated by a gas burner the size of an oil drum. Those who don't sit down take a big slice and eat it like Americans eat pizza, lifting it and seeming to pour it down their throats as they walk.

Part of the plot of my third Palestinian crime novel THE SAMARITAN'S SECRET revolved around my hero's attempts to defy the violence of the casbah to take his granddaughter for a slice of qanafi at a place based on Aksa Sweets. People eat qanafi all over the Arab world, but Nablus is where it was first made and the particular mix of goats' cheeses used here guarantees that it's the best place to eat it.

Here's how it's made:

Published on July 19, 2009 07:44

•

Tags:

east, middle, nablus, palestine, palestinians, samaritan-s, secret

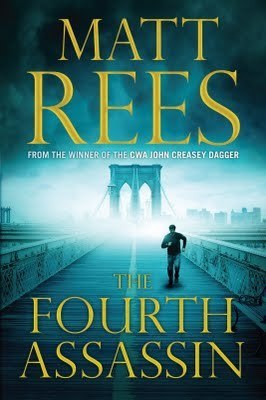

UK cover for THE FOURTH ASSASSIN

It's always a thrill for me to receive the covers of my forthcoming novels from my UK publisher Atlantic Books. They have a series feel in that there's a continuity to the design. Each one seems to get better. Here's the cover of THE FOURTH ASSASSIN, which will be published next February. I received it from my delightful editor in London Sarah Norman just this week.

In THE FOURTH ASSASSIN, Omar Yussef leaves his regular haunts in the West Bank and Gaza Strip. He travels to New York for a UN conference, he's eager to visit his youngest son, Ala, who lives in Bay Ridge, a Brooklyn neighborhood with a large Palestinian community. He arrives at Ala's apartment to find the door ajar and a headless body in one of the beds. He's initially terrified that the dead man is his son, but soon Ala arrives and identifies the body as that of one of his roommates. He's convinced that his other roommate is the killer. But when the cops show up, Ala refuses to give an alibi and is arrested. Desperate to prove his son's innocence, Omar Yussef investigates. The murderer has left clues that refer to the Assassins, a medieval Shiite sect. When they were teenagers, Ala and his roommates had a club by that name. What's the connection? As Omar Yussef delves deeper, he uncovers a deadly international conspiracy.

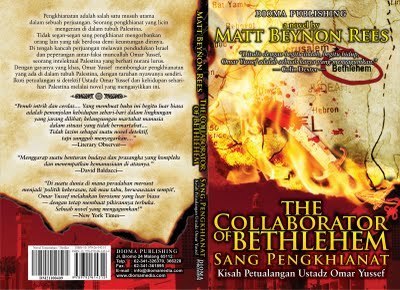

On the subject of covers: My first Palestinian crime novel is just out in Indonesia (the second in the series A GRAVE IN GAZA was published there earlier this year). My wonderful editor at Dioma in Malang, Herman Kosasih, sent me copies of THE COLLABORATOR OF BETHLEHEM with, frankly, one of my favorite covers produced anywhere in the world for any of my books.

In THE FOURTH ASSASSIN, Omar Yussef leaves his regular haunts in the West Bank and Gaza Strip. He travels to New York for a UN conference, he's eager to visit his youngest son, Ala, who lives in Bay Ridge, a Brooklyn neighborhood with a large Palestinian community. He arrives at Ala's apartment to find the door ajar and a headless body in one of the beds. He's initially terrified that the dead man is his son, but soon Ala arrives and identifies the body as that of one of his roommates. He's convinced that his other roommate is the killer. But when the cops show up, Ala refuses to give an alibi and is arrested. Desperate to prove his son's innocence, Omar Yussef investigates. The murderer has left clues that refer to the Assassins, a medieval Shiite sect. When they were teenagers, Ala and his roommates had a club by that name. What's the connection? As Omar Yussef delves deeper, he uncovers a deadly international conspiracy.

On the subject of covers: My first Palestinian crime novel is just out in Indonesia (the second in the series A GRAVE IN GAZA was published there earlier this year). My wonderful editor at Dioma in Malang, Herman Kosasih, sent me copies of THE COLLABORATOR OF BETHLEHEM with, frankly, one of my favorite covers produced anywhere in the world for any of my books.

Published on August 14, 2009 04:52

•

Tags:

assassin, bethlehem, britain, collaborator, crime, fiction, fourth, indonesia, matt, nablus, omar, palestine, palestinians, publishing, rees, samaritans, yussef

Oldest Bible? Tell it to the Samaritans

UK newspaper The Daily Telegraph reports the discovery of a portion of a Bible from 350 AD in the library of the monastery of St. Catherine in the Sinai. The Codex Sinaiticus is written in Greek on animal skin and the newspaper calls it "a fragment of the world's oldest bible." Well, I hate to disappoint the good Fathers in the Sinai, not to mention the hacks at the Torygraph, but there's a much, much older Bible on a hilltop just outside the Palestinian town of Nablus. The Abisha Scroll is used in the rites of the ancient sect of Samaritans. I featured it in my Palestinian crime novel THE SAMARITAN'S SECRET. How old is it? Read these few paragraphs from my novel to find out just astonishingly aged it is:

“Our greatest treasure was stolen, Abu Ramiz,” Ben-Tabia said. He lifted the tips of his fingers to his beard, as though he might pull it out in despair at the thought of such a calamity. “I felt terrible shame that it should be during my tenure as a priest here in our synagogue that the Abisha Scroll might be lost.”

“The Abisha?” Omar Yussef’s voice was low and reverent.

“What’s that?” Sami said.

“A famous Torah scroll,” Omar Yussef said. “The oldest book in the world, they say.”

The priest raised his eyes to the ceiling. “The five books of Moses, written on sheepskin three thousand, six hundred and forty-five years ago. It was written by Abisha, son of Pinchas, son of Eleazar, son of Aaron who was the brother of Moses, in the thirteenth year after the Israelites entered the land of Canaan. Every year, we bring it out of the safe only once, for our Passover ceremony on Mount Jerizim.”

“It must be very valuable,” Sami said.

“It’s beyond all value. Without this scroll, our Messiah can never return to us. Without this scroll, we cannot carry out the annual Passover sacrifice, and if we fail to sacrifice on Passover we cease to be Samaritans and the entire tradition of our religion comes to a terrible close.” The priest’s eyes were moist.

“Our greatest treasure was stolen, Abu Ramiz,” Ben-Tabia said. He lifted the tips of his fingers to his beard, as though he might pull it out in despair at the thought of such a calamity. “I felt terrible shame that it should be during my tenure as a priest here in our synagogue that the Abisha Scroll might be lost.”

“The Abisha?” Omar Yussef’s voice was low and reverent.

“What’s that?” Sami said.

“A famous Torah scroll,” Omar Yussef said. “The oldest book in the world, they say.”

The priest raised his eyes to the ceiling. “The five books of Moses, written on sheepskin three thousand, six hundred and forty-five years ago. It was written by Abisha, son of Pinchas, son of Eleazar, son of Aaron who was the brother of Moses, in the thirteenth year after the Israelites entered the land of Canaan. Every year, we bring it out of the safe only once, for our Passover ceremony on Mount Jerizim.”

“It must be very valuable,” Sami said.

“It’s beyond all value. Without this scroll, our Messiah can never return to us. Without this scroll, we cannot carry out the annual Passover sacrifice, and if we fail to sacrifice on Passover we cease to be Samaritans and the entire tradition of our religion comes to a terrible close.” The priest’s eyes were moist.

Published on September 03, 2009 22:50

•

Tags:

bible, britain, crime, east, fiction, israel, jesus, journalism, london, middle, nablus, omar, palestine, palestinians, religion, samaritan-s, samaritans, secret, yussef

Ass-backwards on Gays

When it comes to homosexuals, Palestinians have it all ass-backwards.

That led me to introduce homosexuality as a theme of THE SAMARITAN’S SECRET, my most recent Palestinian crime novel. I wanted to show how negative attitudes toward homosexuals function in the Muslim world, demonstrating the bloody consequences for gay Muslims and the struggles it causes the people around them. I’m glad I did, particularly after the recent shocking story of a Turkish man living an openly gay lifestyle who was tracked down and murdered by his own father—an honor killing with a difference.

As a novelist who writes about people of a different culture, it’s important not to have the members of that culture think as we’d somehow like them to think, in the West. To have them simply accord with our values.

But I’ve known Palestinian homosexuals and seen their suffering at keeping their real selves secret. Enough to be able to portray those sufferings, as it were, from the inside.

In my novel, the subject also gave me a bit of a conundrum in terms of style.

In each of my novels I’ve translated directly some of the more poetic phrases of local Arabic, as well as slang. So “Good morning” becomes “Morning of joy.” “Get lost” becomes “Fuck your mother’s cunt, you son of a whore.” You get the idea.

The slang word for homosexuals among Palestinians is a little more difficult to translate. Not the word itself, but the negative meaning of it.

Palestinians call homosexuals “Loutis.” “Lout” is the Arabic name for Lot, the brother of the biblical Abraham who was the one good man in the city of Sodom. The man God allowed Abraham to save.

The problem for me was that I couldn’t simply translate the name. To have someone say, “Yes, he’s a Lot-type.” You, dear reader, would wonder what that meant. You might think, “You mean, he’s like Lot, the righteous man. The one man in Sodom who wasn’t sodomizing the other…Sodomites?”

So I had to add a subtle explanation (I hope it’s subtle) that wouldn’t interrupt the conversational flow in the narrative. Here’s the first time the term turns up in THE SAMARITAN’S SECRET, when my detective Omar Yussef is talking with a local sheikh who is of a fundamentalist bent (if you’ll pardon the pun…):

“But I also don’t condemn some of the illogical things people do when their bodies demand it of them,” Omar Yussef said. “For them to do otherwise is to court depression and suicide, and that’s certainly against Islamic law.”

“You can’t mean you see nothing wrong in homosexuality? The holy Koran condemns homosexuals as /Loutis/, the people of Lot from Sodom.”

“Homosexuals suffer enough in our society without me hating them, too.”

“What if you learned that one of your sons was such a pervert?”

Omar Yussef gave a rasping laugh. “I’d blame his mother. But he’d still be my son.”

Of course part of my introduction of gay characters into THE SAMARITAN’S SECRET, which is set in Nablus, was an in-joke that only Palestinians would get. You see, whenever a Palestinian tells a homophobic joke, it’s always about a guy from Nablus who likes to be buggered.

Nabulsi men maintain that their reputation should belong to a group of Iraq soldiers who were stationed in Nablus during the 1948 war with Israel. The Iraqis, according to the men of Nablus, were the true “Loutis.” They raped many young boys from Nablus. So the idea that Nabulsi men tend to homosexuality, they claim, isn’t true.

Recount that “defense” to Palestinians from Jerusalem or Hebron and they’ll laugh that the Nabulsi boys enjoyed the visit of the Iraqi soldiers, which is why the reputation stuck…and on the joking will go.

Life for homosexuals in Nablus or anywhere else in the West Bank is dangerous. Some Palestinians used to sneak into Jerusalem to attend the city’s one gay night club (Israel’s gay culture is centered in Tel Aviv, and most Israeli Jerusalemites are hardly more gay-friendly than the Palestinians, as the man stabbed by a religious gay-baiter during the city’s gay parade four years ago could attest). The Palestinians were the most prominent among the drag queens at the club, which was close to the Jerusalem Municipality.

But the club’s closed now. Palestinian homosexuals simply can’t come out, because their families or neighbors might take a dreadful revenge upon them.

And that’s no joke.

Palestine Scene of the Crime

Crime writer J. Sydney Jones has a new blog called Scene of the Crime. He aims to interview writers about the impact on their writing of the location and sense of place in their novels -- usually from far-flung countries. This week he features me on my Palestinian crime novels. Read on, for the full interview.

Crime writer J. Sydney Jones has a new blog called Scene of the Crime. He aims to interview writers about the impact on their writing of the location and sense of place in their novels -- usually from far-flung countries. This week he features me on my Palestinian crime novels. Read on, for the full interview.A Different View of Palestine

Matt Beynon Rees has staked out real estate in the Middle East for his acclaimed Crime Writers Association Dagger-winning series of crime novels featuring Palestinian sleuth Omar Yussef. The books have sold to publishers in 23 countries and earned him the title “the Dashiell Hammett of Palestine” (L’Express).

His newest, The Fourth Assassin, which is out on Feb. 1, finds Yussef in New York for a UN conference and visiting his son, Ala, who lives in Bay Ridge, a Brooklyn neighborhood with a large Palestinian community. Of course murder and mayhem greet Yussef in New York, just as in Palestine, and he is ultimately forced to investigate in order to clear his son of a murder charge.

Scene of the Crime caught up with Matt in New York, where he is promoting his new book. He was kind enough to take time away from his busy schedule to answer a few questions.

Describe your connection to Jerusalem and Palestine. How did you come to live there or become interested in it?

I arrived in Jerusalem for love. Then we divorced. But I stayed because I felt an instant liking for the openness of Palestinians (and Israelis). When I arrived I had just spent five years as a journalist covering Wall Street. Frankly that exposed me to a far more alien culture than I experienced when I became a foreign correspondent in the Middle East. People in the Middle East are always so eager to tell you how they FEEL; on Wall Street no one ever talked about feelings, just figures. Rotten material for a novel, figures are. I’ve lived now 14 years in Jerusalem.

What things about Palestine make it unique and a good physical setting in your books?

Palestine is a place we all THINK we know. It’s in the news every day. Yet the longer I’ve been there, the more I understand that the news shows us only the stereotypes of the place. Terrorism, refugees, the vague exoticism of the muezzin’s call to prayer. What better for a novelist than to take something with which people believe themselves to be familiar and to show them how little they really know. To turn their perceptions around. The advantage is that I begin from a point of some familiarity – it isn’t a completely alien location about which readers know nothing. Imagine if I’d set my novels in, say, Tunisia or Bahrain. Not far from where my novels take place, but much more explanation needed because they’re rather a blank. With Palestine, I’m able to manipulate and disturb the existing knowledge of the place we all have.

Did you consciously set out to use Palestine as a “character” in your books, or did this grow naturally out of the initial story or stories?

I arrived in Jerusalem as a journalist, but I’ve felt that I’m on a vacation every day of those 14 years I’ve lived there. Every minute I spend in a Palestinian town or village, my creative senses are heightened, to the point where it becomes quite exhausting. Part of that is because of the people, the way they speak and feel. But most of it is the experience of place. The light so bright off the limestone. The smells of spices and shit in the markets. The cigarette smoke and damp in the covered alleys. It’s important to note that each Palestinian town is extremely distinctive – which might not be evident from the news. My first novel takes place in the historic town of Bethlehem. The second is in Gaza, which seems like another world. Nablus, where the third book is set is an ancient Roman town, built over by the Turks. …My new novel sees my Palestinian detective Omar Yussef come to Brooklyn. I move him around BECAUSE place is the driver of the novels. The main characters are the same; but I draw something different out of each of them by shifting them to new places.

How do you incorporate location in your fiction? Do you pay overt attention to it in certain scenes, or is it a background inspiration for you?

The texture of a Palestinian town is so rich, it ends up defining the atmosphere of the novel. With the casbah of Nablus for example: I was stuck in its old alleys during the intifada with gunfire all around, not knowing who or what might be round the next corner, and it seemed so sinister and beautiful at the same time. The locations are more than background. They’re significant because I write about Palestinian culture and society and people, in the context of a mystery. You couldn’t take my mysteries and change the names and put the Golden Gate in the background and say they were set in San Francisco. They’re the books they are because Palestine is as it is.

How does Omar Yussef interact with his surroundings? And conversely, how does the setting affect him?

Omar Yussef, my detective, is based on a friend of mine who lives in Dehaisha Refugee Camp in Bethlehem. It’s important to me that he should be a Muslim, someone who loves his traditional family life and tribe, someone who belongs very deeply to Bethlehem. That’s because I’m trying to show readers what they’re missing when they see the Palestinians only as stereotypical terrorists or victims. His reaction to the chaos around him is that of an honorable man who finally is driven to stand up against the negative forces at work in his town.

Has there been any local reaction to your works? What do local Palestinian and Israeli reviewers think, for example. Are your books in translation in Palestine, and if so, what reaction have they gotten from reviewers?

Hanan Ashrawi, a former Palestinian peace negotiator and a leading political figure, said of The Collaborator of Bethlehem that “it reflects the reality of life in Bethlehem– unfortunately.” (After all, it’s a crime novel of exceeding chaos.) I get a lot of emails from Arabs noting that I’m showing the reality of their people in a way that isn’t reflected in Arab media – which just blames Israel for everything – or in Western media, where the Palestinians are usually just stereotypes set in opposition to Israel. Translation into Arabic is a slow business – Henning Mankell sold 40 million books before he got an Arab translation last year – but I’m hopeful. Meanwhile the first book was translated into Hebrew and got good reviews. Israelis were very glad to have an opportunity to learn about life beyond the wall that they’ve built between Jerusalem and Bethlehem.

Of the novels you have written set in Palestine, do you have a favorite book or scene that focuses on the place? Could you quote a short passage or give an example of how the location figures in your novels?

In my third novel. The Samaritan’s Secret, there’s a scene in an old palace in the Nablus casbah called the Touqan Palace. This was the real palace I discovered on my first visit to the West Bank (to cover the funeral of a man who’d been tortured to death in the local jail). I finished my reporting and went for a walk about the casbah. I’d heard about the Touqan Palace and a friendly Palestinian helped me find it. We shouldered open the door, climbed through the goat pen inside, and came into a courtyard strung with cheap laundry and with chickens living in the ornate fountain at the center. The wealthy family that built the palace had moved to a new place up the hillside; now the palace was home to poor refugees. It struck me very powerfully as a political irony. But I also loved the stink of the chickens and the way the goats nuzzled at me and the children who lived there came through the dust to chat with me. I tried to get that feeling of a people estranged from their history into the novels through Omar Yussef, who’s a sleuth but also a history teacher. So the scenes in the Touqan Palace are quite pivotal, thematically, for me.

Who are your favorite writers, and do you feel that other writers influenced you in your use of the spirit of place in your novels?

I love Paul Bowles (The Sheltering Sky, Let it Come Down). He used to travel the Arab world and, each day, would incorporate into his writing something that had happened the previous day as he journeyed. That’s a technique I’ve used. It makes you look sharply at the emotions you experience when you’re in a strange place. In some ways it was most useful when I wrote The Fourth Assassin, which is set in Brooklyn. I know New York very well but I made a great effort to see the place as a new immigrant or a total foreigner might. I discovered that it was daunting and oppressive and crowded and huge and threatening and cold as hell – it actually made me a little depressed. Which was the point of doing my research that way. I think of it as method acting for writers.

Visit Matt at his homepage, and also on his blog. Thanks for the insightful comments, Matt, and good luck with the new book.

Published on February 02, 2010 07:09

•

Tags:

bethlehem, brooklyn, crime-fiction, exotic-fiction, gaza, golden-gate, interviews, israel, j-sydney-jones, jerusalem, matt-beynon-rees, middle-east, nablus, new-york, omar-yussef, palestine, palestinians, san-francisco, the-fourth-assassin, writing

Why I love clogged Arab toilets better than Amazon Kindles

As I travel the Middle East to research my Palestinian crime novels, I love to come upon a stinking squatting-toilet, its evacuation hole bubbling with dark, sinister turds and the air strong with the scent of barely digested, unhygienically prepared lamb kebab. I adore such a khazi on sight, because no one cleaned it up for me or tried to create an illusion that it was just like a toilet in Manhattan or Munich or my mother’s house.

As I travel the Middle East to research my Palestinian crime novels, I love to come upon a stinking squatting-toilet, its evacuation hole bubbling with dark, sinister turds and the air strong with the scent of barely digested, unhygienically prepared lamb kebab. I adore such a khazi on sight, because no one cleaned it up for me or tried to create an illusion that it was just like a toilet in Manhattan or Munich or my mother’s house.That toilet is suddenly all around me and it’s real, down to the ragged little cloth and the old watering can for washing myself afterwards. I can even remember the most spectacularly smelly ones, like the reeking mess of my hotel toilet in Wadi Moussa, Jordan, where I paid $1.60 per night for a room, or the delightful filth of the Fatah headquarters in Nablus.

According to Virginia Heffernan, The New York Times television and “media” columnist, the sensuous depth of my experiences with Palestinian toilets is worthless. Every time I crap, I ought to be doing it in a replica of the Tokyo hotels which spray your backside with hand cleansing soap solutions, whether you like it or not.

How did Heffernan get into my toilet habits? Well, she didn’t. Actually she told me that the scent of books not only doesn’t matter but is a subject she finds tedious. The “aria of hypersensual book love is not my favorite performance,” she writes this week. “I sometimes suspect that those who gush about book odor might not like to read. If they did, why would they waste so much time inhaling?”

So if you like food, do you have to choose one sense as the limit of your experience? If you're invited out to eat with Heffernan: Don’t look at the plate and don’t savor the aroma; just eat the bloody thing.

The lady ought to get out more and think about her own senses. Most people only seem to notice smell when it makes them wrinkle their nose in disgust.

Whenever I’m in a Palestinian town, I can hardly breathe for all the sniffing I do. Strong cigarettes, body sweat, dust that seems superheated, donkey dung, cardamom from the coffee vendor and other spices in sacks outside a shop. The connection between scent and memory is in fact much stronger than the link between sight and our memories.

So forgive me if I go home from the Palestinian john and give my library the same attention.

I should add that Heffernan’s weird article posits the arguments of the great philosopher Walter Benjamin in favor of the love of a library, its scents and sense of touch. She then puts forward her argument in favor of e-readers which is that… Well, as far as I can see it’s just that she thinks Benjamin would probably have liked the Kindle, even though all the things he says he likes about books in his essay on collecting books don’t conform to the Kindle experience (except for the actual words you read).

It’d be like me writing that my old college tutor Terry Eagleton (author of “Walter Benjamin, or Toward a Revolutionary Criticism” 1981) wanted to elucidate a way for socialist literary critics to utilize new French deconstructionist techniques (true), only to add that he’d probably think Heffernan was a tasty bit of crumpet (probably true, knowing Terry, but no more than a hunch on my part.)

I’m not against the Kindle or other e-readers. I think it’s quite possible that many people will read more because of the ease with which they can download a range of works onto their little screens. One of my good friends here in Jerusalem loves his Kindle and has noted that, while I have to wait weeks for my books to be delivered, he can be reading whatever he wants in the seconds it takes to download a digital file.

My pal also points out that e-readers might be good for authors in the end (despite the fears of publishers) because he can’t lend my books once they’re bought on his Kindle. He has to buy another copy as a gift. See, I’m all for that.

Heffernan’s argument falls in line with the thoughtless cool accorded often-useless gadgets by people who haven’t looked beyond the sleek design and beeping sounds. (By this I mean the following conversation which I’m sure you’ve all experienced: “It’s cool.” “Why?” “It’s just cool, man.”)

Heffernan bloviates about scrolling through her “odorless dustless Kindle library,” comparing that with a dusty, odoriferous real library. But when she’s scrolling, she oughtn’t to compare herself to people who love books. The best comparison is to people who love card catalogues, because she isn’t looking at the books, only at their titles and some other referents.

“I have literally no memory of opting to get any of these books on Amazon,” she writes as she breezes down the list of contents on her snazzy device. That, Virginia dear, is because though it’s called a “Kindle,” you’re reading a computer. When I look at my computer, I often can’t remember when I wrote any number of blog posts or news stories based on a perusal of their file names. A few words in a digital list are nothing more than that. They have no design, no sensual triggers, no other association at all.

But I remember where and when I bought almost every book I own. (I also have a special place in my heart for the ones I stole as a teenager, but it turns out that might be easier to do with digital devices as well. Another thrill of youth lost to new technology.)

“The Kindle delivers a new kind of bliss,” Heffernan concludes. I’m sure it does, though Heffernan can’t tell us what that bliss might be.

Meantime, don’t forget about books. And, in spite of what I wrote above, don’t forget to flush.

(I posted this on a blog I write with three other international crime authors. Check it out. For more of my own blog post, visit my blog: The Man of Twists and Turns.)

Published on March 11, 2010 06:17

•

Tags:

amazon-kindle, arab, crime-fiction, fatah, gaza, jerusalem, jordan, kebab, media, middle-east, nablus, palestine, palestinian, squatting-toilet, television, terry-eagleton, the-new-york-times, toilet, tokyo, virginia-heffernan, wadi-moussa, walter-benjamin, west-bank