Matt Rees's Blog - Posts Tagged "the-samaritan-s-secret"

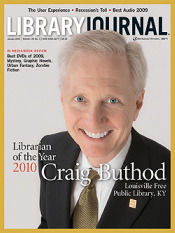

In new Palestinian crime novel NYC dangerous as West Bank

In the current Library Journal, my new Palestinian crime novel, THE FOURTH ASSASSIN (out Feb. 1) gets a good review that highlights the themes and implications beyond the resolution of the mystery. For those who have no copy of the magazine (in which case you may have missed Librarian of the Year -- Way to go, Craig Buthod of Louisville, Ky.) here's THE FOURTH ASSASSIN review: "In New York City for a UN conference, Omar Yussef goes to Bay Ridge, Brooklyn, home to a large Palestinian community, to visit his son and finds a beheaded body in his son's apartment. With no alibi, his son is arrested, and Omar finds that the streets of New York are as treacherous and dangerous as those of Bethlehem. VERDICT Journalist Rees's fourth Omar Yussef outing (after The Samaritan's Secret) exposes the political struggle among various Palestinian factions and demonstrates why it is so difficult to find a solution in the troubled region. His sleuth might miss the ancient streets of Bethlehem, but the hatred and tension of the Middle East follow the Palestinian wherever he goes."

In the current Library Journal, my new Palestinian crime novel, THE FOURTH ASSASSIN (out Feb. 1) gets a good review that highlights the themes and implications beyond the resolution of the mystery. For those who have no copy of the magazine (in which case you may have missed Librarian of the Year -- Way to go, Craig Buthod of Louisville, Ky.) here's THE FOURTH ASSASSIN review: "In New York City for a UN conference, Omar Yussef goes to Bay Ridge, Brooklyn, home to a large Palestinian community, to visit his son and finds a beheaded body in his son's apartment. With no alibi, his son is arrested, and Omar finds that the streets of New York are as treacherous and dangerous as those of Bethlehem. VERDICT Journalist Rees's fourth Omar Yussef outing (after The Samaritan's Secret) exposes the political struggle among various Palestinian factions and demonstrates why it is so difficult to find a solution in the troubled region. His sleuth might miss the ancient streets of Bethlehem, but the hatred and tension of the Middle East follow the Palestinian wherever he goes."

Published on January 19, 2010 05:37

•

Tags:

bay-ridge, bethlehem, brooklyn, crime-fiction, kentucky, library-journal, louisville, manhattan, matt-beynon-rees, middle-east, mystery-fiction, new-york, omar-yussef, palestinian, reviews, the-fourth-assassin, the-samaritan-s-secret, u-n

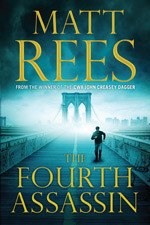

'The Fourth Assassin' takes Page 69 Test

The Campaign for the American Reader blog empire's flagship is the Page 69 Test. The premise of the blog is this: open any book to page 69; if it grabs you, that's a better indication of whether you'll enjoy the book than simply reading the opening page. Try it on a book you like (and, maybe more fun, one you don't), it's pretty reliable. Blogger Marshal Zeringue asked me to submit my new Palestinian crime novel, THE FOURTH ASSASSIN, to the Page 69 Test. Here's his introduction followed by what I wrote for him about page 69 of my new book:

The Campaign for the American Reader blog empire's flagship is the Page 69 Test. The premise of the blog is this: open any book to page 69; if it grabs you, that's a better indication of whether you'll enjoy the book than simply reading the opening page. Try it on a book you like (and, maybe more fun, one you don't), it's pretty reliable. Blogger Marshal Zeringue asked me to submit my new Palestinian crime novel, THE FOURTH ASSASSIN, to the Page 69 Test. Here's his introduction followed by what I wrote for him about page 69 of my new book:Matt Beynon Rees is the author of the acclaimed series of novels featuring Palestinian detective Omar Yussef: The Collaborator of Bethlehem, which won the CWA John Creasey (New Blood) Dagger award, A Grave in Gaza, The Samaritan's Secret, and the newly released The Fourth Assassin.

He applied the Page 69 Test to the new novel and reported the following:

The first three novels in my Palestinian crime series take place in the West Bank and Gaza. All the characters are Palestinian, with the exception of a couple of foreign aid workers. But I want my series to show the full extent of Palestinian life, and half the people in the world who call themselves Palestinian don’t live in Palestine. So my hero Omar Yussef hits the road.

The Fourth Assassin, the new book in my series, takes place in the UN on the east side of Manhattan, and in the section of Bay Ridge, Brooklyn, that’s becoming known as “Little Palestine,” as immigrants from the Jerusalem area make it their home.

Page 69 hits the two main topics that make the book compelling.

First, the alienation felt by a foreigner when confronted with the enormity and chaos of New York. I wanted to show how immigrants might turn inward, rejecting the society around them, becoming religious fundamentalists. Here’s the description of a subway ride from Omar’s point of view:

"The train rumbled at low speed onto the strangely terrifying superstructure of the Manhattan Bridge. Downriver, beyond the massive girders and the mesh of electric lines, the Brooklyn Bridge arched over the water. Its famous towers sprayed thick cables along its span. Omar Yussef felt as though he were flying out of control through the air, high above the river and the tangle of highway along the shoreline. An old Vietnamese man screamed into his cell phone over the noise of the train. The wheels rang like the slow beating of a giant steel kettledrum until the train slipped back under the earth, jumped to a different track, and picked up speed. ‘This is an unnatural way of traveling,’ Omar Yussef whispered."

Second, Page 69 contains an important spark for the mystery at the heart of the book. Up to this point, no one but Omar Yussef acknowledges that things seem awry. But now his sidekick, Bethlehem Police Chief Khamis Zeydan, says to him:

"‘My brother, I have a bad feeling about this visit. Some danger that I can’t predict.’"

Now if that doesn’t hook you, nothing will. Read on to page 70, eh?

Published on February 08, 2010 11:47

•

Tags:

a-grave-in-gaza, bay-ridge, blogs, brooklyn, crime-fiction, exotic-fiction, little-palestine, marshal-zeringue, new-york, omar-yussef, the-collaborator-of-bethlehem, the-fourth-assassin, the-page-69-test, the-samaritan-s-secret, united-nations

The Daily Beast and The New York Times

My new Palestinian crime novel THE FOURTH ASSASSIN is one of five "This Week's Hot Reads" on The Daily Beast, which is also the hot read of the web these days. The Beast says of my book and its Brooklyn setting: "Rees paints a meticulous portrait of the post-9/11 community of Little Palestine and the tension of cultures trying to co-exist."

My new Palestinian crime novel THE FOURTH ASSASSIN is one of five "This Week's Hot Reads" on The Daily Beast, which is also the hot read of the web these days. The Beast says of my book and its Brooklyn setting: "Rees paints a meticulous portrait of the post-9/11 community of Little Palestine and the tension of cultures trying to co-exist."Meanwhile, The New York Times Book Review highlights the paperback release of my previous novel THE SAMARITAN'S SECRET in its Paperback Row column, calling the book "provocative and humane." Seems The Times'd rather print a nice photo of me than one of Jimmy Carter, too. Well, the old boy had his time in the sun.

Published on February 13, 2010 23:31

•

Tags:

9-11, bay-ridge, brooklyn, crime-fiction, jimmy-carter, little-palestine, matt-beynon-rees, new-york, new-york-times-book-review, paperback-row, the-daily-beast, the-fourth-assassin, the-samaritan-s-secret

In Nablus, the price is right

I was tucking into a slice of qanafi at my favorite vendor in the Nablus casbah yesterday when a gang of Palestinian reporters and officials intruded on my guilty pleasure. This was at Aqsa Sweets, which readers of THE SAMARITAN'S SECRET will know as the place favored by the hero of my Palestinian crime novels Omar Yussef because it has a perfect blend of the cheeses of different Syrian and Palestinian goats in its qanafi (topped by semolina and drenched in syrup.)

I was tucking into a slice of qanafi at my favorite vendor in the Nablus casbah yesterday when a gang of Palestinian reporters and officials intruded on my guilty pleasure. This was at Aqsa Sweets, which readers of THE SAMARITAN'S SECRET will know as the place favored by the hero of my Palestinian crime novels Omar Yussef because it has a perfect blend of the cheeses of different Syrian and Palestinian goats in its qanafi (topped by semolina and drenched in syrup.)Mayor Adly Yaish was among the crowd. As he steamed his way through a plate of qanafi, he informed me that he, the Nablus region's governor, and the city's police chief were touring the casbah to draw attention to a law soon to come into effect that'll make it mandatory for vendors to show their prices. It's one of the economic reforms introduced by Prime Minister Salaam Fayyad, a Nablus native, intended to change the chaotic and often corrupt nature of the Palestinian economy.

A few minutes of jawboning with me about their hopes that my books will show the true Nablus (I think they do, but I didn't remind them that I write crime fiction), a forkful of qanafi raised for the cameras, and then the dignitaries were off into the narrow alleys in search of price tags.

I settled in to complete my lunch -- not a balanced diet, I know, but then my mother doesn't read this blog so I don't have to pretend to be watching what I eat. I washed it down with tea from a fellow who wandered in with an enormous pot and a cup of sugar in his apron.

Nablus is famous throughout the Arab world as the best place for qanafi. And Aqsa Sweets is the best qanafi in Nablus, thus the best in the Arab world and, obviously, in the world. You wouldn't know it. The place is floor to ceiling white ceramic tiles, as though they expected to hose it down at the end of the day. Up front there are two big burners with wide trays of orange qanafi. The surly fat kid who serves you slings it onto the table as though he thought frisbees were made of hot goat's cheese and syrup.

As for price, nothing's marked. For 4 shekels (a bit more than a dollar), you get 125 grams of qanafi. It doesn't look like much, but if you try to eat more than that, you'll either stagger out hoping never to see another piece of the stuff in your life, or you might just curl up and die in the corner of sugar-shock.

I went up Mount Gerizim, one of the two mountains whose steep sides form the valley in which Nablus lies. At the top I found my old pal Hosny Cohen, a Samaritan priest, in exultant mood. He's shifting his Samaritan Museum and Cultural Center to a bigger room.

"I've had two tour groups this morning, each of forty people," he said, leaning on his cane and pushing his fez forward neatly over his brow. "I don't have energy for you."

Then he proceeded to talk for an hour without stopping. When I was about to leave, he came after me and said: "I forgot to show you the 'mezuza' we put above the door..."

Which is why I can't help liking the Middle East.

Published on March 16, 2010 10:54

•

Tags:

adly-yaish, aqsa-sweets, crime-fiction, dessert, food, goats, hosny-cohen, mayor, nablus, palestine, palestinian, prime-minister, qanafi, salaam-fayyad, samaritans, syria, the-samaritan-s-secret

Back to Israel: Recall what's foreign

When you live in a foreign place, it can become home. You forget how foreign it is.

When you live in a foreign place, it can become home. You forget how foreign it is.Then you go to another foreign country, only to discover that it doesn’t seem so foreign. And you realize that the place you live actually IS extremely foreign.

That’s what happened to me during the last week, when I toured Germany to read from my third Palestinian rime novel THE SAMARITAN’S SECRET (just published by CH Beck Verlag as “Der Tote von Nablus.”)

I was in Munich station when I noticed in a pastry shop that Germans spell pretzel with a B (“Brezel”). I felt a little blown away, as though I’d been living a lie all these years offering my son “pretzels.” But that’s as foreign as Germany got. Otherwise, this Welshman felt right at home there.

Right off the plane on my return to Israel, however, the country which has been my home since 1996 and where I’ve grown accustomed to the way people behave, the foreignness hit me anew.

Actually even before that. The fellow in the seat next to me on the flight from Frankfurt kept talking to me – Israelis have a way of talking a lot and they can also be rather clueless about my oh-so-subtle signals that I’d rather read my book. While I was eating, he reached over and took part of my bread roll with a smile and gentle touch of my forearm. (Bread is something you share in Middle Eastern meals, although it usually applies to pita and flatbread, not to tiny airline rolls. This was pretty extreme space-invasion, even for a Middle Easterner, but the reassuring friendly gestures while he was taking advantage of me were very familiar.)

Then in the airport, the dimensions of personal space shrank from the yard kept by Germans to an elbow-brushing, back-nudging Middle Eastern minimum. I smiled, because the Tel Aviv airport is very flashy and new – you could be anywhere in the world. But it’s most definitely not the unflustered calm of Dresden airport, where I boarded my first flight of the day.

Arrival in a “foreign” country means a lot of things that’ll sound deeply negative – or at least they’ll sound like I’m being negative. The shoving and noise and the passport lines where people don’t actually wait in line but prefer to edge around you. But I’m not entirely negative about them. I like it (mostly), because I enjoy being an outsider. To be sure, I don’t think I’d like it much if I looked around and thought, “These are my people. This is my culture. This is ME.”

Then, I expect I’d want us to be more organized, more respectful of each other, less suspicious, more…foreign.

As I emerged into the humidity of the plains between Tel Aviv and the Judean Hills, it struck me that “foreign” countries are simply the ones where things aren’t even remotely fair. That’s why everyone at the Tel Aviv airport hovers over the baggage carousel, shifting from foot to foot, edging in front of others closer to the bags. It suggests an absolute fear that the bag never will come and, most of all, that if all the bags happened to arrive all at once you must be the first one to grab yours and get away before the other suckers. Life in a “foreign” country is a zero-sum game, in which someone else’s success or happiness comes somehow at your expense and must be envied, hated, usurped.

That’s not a German quality. Germans have a sense that there’s some degree of fairness in their society and it makes relations between them less devious and Machiavellian, less on the make. They drive fast, but they don’t think someone else driving fast is attacking them on a macho level, signaling superiority and disdain for them, and, thus, respond by semi-subliminally trying to run them off the road.

So here I am, back in Jerusalem, back to being a foreigner.

Though I shouldn’t forget that at least Israelis spell pretzel with a P.

(I posted this on International Crime Authors Reality Check, a joint blog I do with some other crime writers. Check it out.)

Published on March 25, 2010 07:35

•

Tags:

blogs, crime-fiction, der-tote-von-nablus, dresden, frankfurt, germany, israel, israelis, jerusalem, middle-east, munich, tel-aviv, the-samaritan-s-secret

Bibi's Bedtime Book: The Secret Diary of Prime Minister Netanyahu

No Palestinian state this week. Don’t really know why not. At this point I’d be happy to sign off on anything at all, just to get it off my hands. I’ve told the Americans that, but they seem convinced I’m some kind of hardliner—they think I’m bluffing when I say “Barry, where do I sign?” I think it’s because of the way I lift my eyebrow in my official photograph. I thought it was sexy and devil-may-care, but apparently it makes me look hawkish and too clever for my own good.

No Palestinian state this week. Don’t really know why not. At this point I’d be happy to sign off on anything at all, just to get it off my hands. I’ve told the Americans that, but they seem convinced I’m some kind of hardliner—they think I’m bluffing when I say “Barry, where do I sign?” I think it’s because of the way I lift my eyebrow in my official photograph. I thought it was sexy and devil-may-care, but apparently it makes me look hawkish and too clever for my own good.It’s been Passover here in Israel. I’ve had to smile and shovel down the usual seasonal foods. I even had to sit through a seder. We were slaves in Egypt, etc., on and on for six hours. You’d have thought we’d be done with all that now. It’s like Zionism never happened.

I gather they had a seder at the White House, too. Without me. Maybe I’ll have Kwanzaa at my villa in Caesarea this year and I pointedly won’t invite Obama. On second thoughts, the rabbis wouldn’t like it. They don’t like holidays where you sing in tune – strictly tuneless, out of time, Jewish mumble-singing is more their thing.

I went down to Shaul’s Shawarma stand to mix with the people. Mofaz insists on meeting there – he set the place up as something to fall back on if he doesn’t get to be Prime Minister instead of me; he could retire, stop wearing his colorless rep ties, and instead bore all his customers with stories of how his political career was a victim of the Ashkenazi establishment. He served me some kind of stinking horsemeat impacted under high pressure into a block so that it looked like an actual cut of meat. I called him “my brother,” which is how Israelis who aren't from the Ashkenazi elite like to refer to each other, and went off to find a breath mint. I suppose he thought the joke was on me.

I’ll eat anything, provided someone else is paying, of course. That’s why I got into politics. Even when I wasn’t in office, at the end of a meal, I’d pat my jacket and say, “Sara, did you bring my wallet?” And some guy from Los Angeles would always reach out and say, “No, no, Mister Prime Minister, let me.”

Why do they say “Mister Prime Minister?” Or Mister President? These are nouns, aren’t they? You don’t call the man who fixes your toilet “Mister Plumber.” On the occasions when I’ve met this Rees fellow I didn’t call him “Mister Writer.” It’s not even necessary for my wife to call me “Mister Big Shot” when she’s upset with me. “Big Shot” would do. I suppose “Mister” adds a grace note to her sarcasm.

Mainly such things are all about self-aggrandizement. Still, just so long as they pick up the tab for my steak and lobster, I’ll let it slide.

Talking of self-aggrandizement, Defense Minister Napoleon puffed out his little chest and humiliated the head of the army this week. Something silly to do with not extending the chief of staff’s term because he didn’t kiss up (figuratively, because in reality everybody would have to bend down to kiss that shortass). Perhaps he’d neglected to call him “Mister Defense Minister.” Or “Mister Bonaparte.” Or “My Emperor.”

Anyway, someone else’s troubles are usually a sign that someone’s too busy elsewhere to ruin my week. So it’s good news. I’ve barely been in the headlines all Passover.

Why am I shy of the press? I keep getting slated for being a hardliner, that’s why. Yet it’s little Napoleon who flattened Gaza and ballsed up the “peace process” a decade ago. I thought we were rid of him once he got onto the $50,000 a night speaking tour in the US. I suppose he had to come back for a while to keep in the public eye, then in a few years he can be President, which isn’t a real job (though I haven’t told Peres that.)

No, I don’t understand the press. Take that fellow Matt Beynon Rees. He came to my office a while back and smoked one of my long Cubans. I told him about my interpretation of the work of Emmanuel Kant, but all he wrote about in the end was a few things I’d said about building in our settlements in Judea and Samaria.

I gather Rees also concluded that journalism is a waste of time. He’s writing fiction now. Crime novels about a Palestinian detective. I must take a look at them. I gather my pal Arafat doesn’t come out too well in one of them called “The Samaritan’s Secret”. A shame. I’m rather fond of the sneaky old “ra’is”, of blessed memory.

Maybe I’ll give it all up and write some fiction myself. About an Israeli Prime Minister who’s misunderstood, who only wants to make people happy and give everyone he talks to exactly what they want. A state for the Palestinians. More ritual baths for the ultra-Orthodox. A free Mazda for the 6 percent of Israelis who don’t already own one. The Legion d’Honneur for the Imperial Defense Minister.

Yes, I might just write a book like that. I think it’d be a good read.

But no one would believe it.

[Prime Minister Netanyahu will be continuing to disclose his most secret thoughts exclusively on this blog].

Published on April 08, 2010 01:12

•

Tags:

barack-obama, benjamin-netanyahu, bibi-s-bedtime-book, crime-fiction, ehud-barak, israel, israeli-politics, israelis, matt-rees, palestine, palestinians, shaul-mofaz, the-samaritan-s-secret

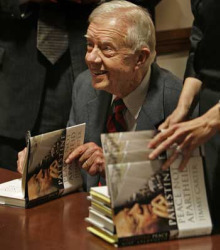

Jimmy Carter, apartheid, hemorrhoids and Matt Beynon Rees

I often receive emails from book stores, amazon.com, Barnes and Noble, and online literary sites telling me how much I’d like the novels of Matt Beynon Rees. I’m delighted to see these emails, which are based on my other purchases and interests, as only I can truly know just how much the novels of Matt Beynon Rees have changed my life. (Try them, I’m sure you’ll agree.)

I often receive emails from book stores, amazon.com, Barnes and Noble, and online literary sites telling me how much I’d like the novels of Matt Beynon Rees. I’m delighted to see these emails, which are based on my other purchases and interests, as only I can truly know just how much the novels of Matt Beynon Rees have changed my life. (Try them, I’m sure you’ll agree.)Of course, I also get the occasional email informing me that if I like Matt Beynon Rees, I might also enjoy another author named in the email. Well, they’re half-way there, because of course I DO like Matt Beynon Rees. No ifs. So I always have to look to see if they’re right about the second part.

The links are sometimes obvious – “if you like Matt Beynon Rees, try [insert crime novelist’s name here:]” – and occasionally baffling though thought-provoking. I had one a few weeks back suggesting fans of Matt Beynon Rees’s Palestinian crime series would really dig a nonfiction book about a cyclone that hit Burma in 2008.

The latest of these connections was no doubt the most bizarre. I clicked on an email from an online book blog a few days ago: “If you like Matt Beynon Rees, we think you’ll enjoy Jimmy Carter.”

Wow, I thought, how did they know that I, too, have lusted after women in my heart.

It could be that the connection was the result of the review of the paperback version of my third Palestinian crime novel THE SAMARITAN’S SECRET in The New York Times—it was featured in the same column as a review of the softcover edition of the 39th President’s ultra-controversial 2006 work of nonfiction “Palestine – Peace Not Apartheid.”

Now here’s where I part with the “If you like Matt Beynon Rees, we think you’ll enjoy Jimmy Carter” email. Of you like Matt Beynon Rees, you’ll probably enjoy crime fiction. Or just fiction. Rather than “Palestine – Peace Not Apartheid,” in which the loveable old peanut farmer from Georgia accuses Israel of the worst kind of discrimination against Palestinians in the West Bank.

I don’t have an opinion on Jimmy’s book. I never read it. It has “Palestine” in the title and, as Graham Greene wrote, once one has lived in a place for a while one ceases to read about it.

Also it has “Apartheid” in the title. I have an opinion about what Israel does in the West Bank. I’m not going to get into it here, but in a (pea)nutshell, I think it’s a mistake to compare Israeli policy to apartheid, because then the debate shifts to the similarities and differences between South Africa’s old regime and Israel’s occupation – instead of talking simply about what Israel does and what’s wrong with it.

As soon as Smiling Jim put “apartheid” in his title, his book’s content was largely ignored. Pro-Israel mouthpieces could condemn him as an anti-Semite simply for comparing Israel to the unlamented and certifiably pariah regime in Pretoria. Game over. Jimmy even issued an apology a couple of years ago to all Jews on Yom Kippur. As though saying something critical of Israel is somehow a criticism of all Jews. As though there weren’t any Jews who agreed with him about Israel’s policy toward the Palestinians. Game over with a slamdown.

For me, as for many others, Carter has been a mildly useful voice for decency in the world. Though he also represents something a little pitiful, as one might witness in the song “Jimmy Carter” by my favorite band, Detroit whacksters Electric Six:

“Like Jimmy Carter,

Like electric underwear,

Like any idea that never had a chance of going anywhere….”

However, the decisive element in the question “If you like Matt Beynon Rees, we think you’ll enjoy Jimmy Carter” is a matter of personal animus. In fact, it’s a family insult suffered by the Rees’s of 32 Neath Road, Maesteg, Mid-Glamorgan, Wales, at the hands of James Earl Carter Jr., 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue, Washington, D.C.

My grandfather Tom Rees read in the Western Mail that then-President Carter was suffering from hemorrhoids. Tom had faced the same ailment some years before and had found nothing eased the feeling of defecating broken glass, until he switched to Allinson’s wholewheat bread. He wrote a letter to the White House in his careful cursive script, letting the leader of the Free World know what he needed to do to poop painlessly.

He didn’t expect any public recognition. But he assumed he’d get a polite note.

Perhaps Carter’s people knew that my grandfather was a former Communist Party member and figured the brown bread was a plot of some sort to keep the Commander-in-Chief on the can and away from the nuclear button, while the Reds swarmed Capitol Hill. In any case, the President never wrote back. Not even a “President Carter has read your inquiry with interest, but regrets that he will not be able to make it part of United States planning and policy at this time, though he is sympathetic to your cause.”

My grandfather continued to consume wholewheat bread, even at a time (the 1970s) when those around him considered it to be a strange fad akin to today’s no-nightshades tomato-free diets.

That’s why I don’t like Carter. Not because of apartheid. Because of hemorrhoids.

I wonder if Jimmy ever got them cured. Maybe he mentions it in his book. Perhaps I ought to read it after all…

Published on May 20, 2010 06:43

•

Tags:

amazon-com, apartheid, barnes-and-noble, crime-fiction, detroit, electric-six, fiction, georgia, glamorgan, graham-greene, hemorrhoids, israel, jews, jimmy-carter, maesteg, matt-beynon-rees, middle-east, new-york-times, palestine, palestine-peace-not-apartheid, palestinian, pennsylvania-avenue, pretoria, south-africa, the-samaritan-s-secret, wales, washington, west-bank, white-house, yom-kippur

Cheers for Hitler, and Brits go home

The company you keep can put the culture around you in a new light, let you see it as you haven’t before.

The company you keep can put the culture around you in a new light, let you see it as you haven’t before.That’s true when I travel to different countries and discover that readers in Germany have a particular take on my Palestinian crime novels which differs from the way they look to Americans, for example.

I got to thinking about this when I was wandering the Nablus casbah this week with two German friends. An enthusiastic Palestinian fellow asked me to explain to them how much he appreciated Hitler, and as an afterthought he noted that all his people’s problems are caused by me and my compatriots from the British Isles.

I had just climbed up the old Turkish clocktower in Manara Square at the heart of the casbah with one of the Germans. I’d never seen the door at the bottom open before, but there was a policeman inside on this occasion and he generously allowed us to go up the ladder. On the first balcony, I stepped through more pigeon feces than I’d have thought could possibly gather in one place. It was crusty for an inch or two, then a little slushy beneath. I had a grin all over my face of the kind that tends to appear there when I discover a new corner in a place I’ve often been – and loved being there – before.

Read the rest of this post on my blog The Man of Twists and Turns.

Published on June 17, 2010 01:33

•

Tags:

barry-unsworth, bedouin, berlin, crime-fiction, damascus, dehaisha-refugee-camp, george-w-bush, germany, hamas, hitler, imperial-camel-corps, jerusalem, middle-east, nablus, omar-yussef, ottomans, palestine, palestinians, the-rage-of-the-vulture, the-samaritan-s-secret, tony-blair, turkey, wales

Overturning detective fiction: everyone's guilty in my novels

The “Golden Age” of the detective story was the 1920s and 1930s. It was a turbulent period. In Britain, the General Strike. In the U.S., the Depression. Civil war in Spain, and in Germany the rise of the Nazis. Red scares everywhere, fascists too.

The “Golden Age” of the detective story was the 1920s and 1930s. It was a turbulent period. In Britain, the General Strike. In the U.S., the Depression. Civil war in Spain, and in Germany the rise of the Nazis. Red scares everywhere, fascists too.But the detective story was a solace to those who lived in such ugly times. In the model employed by Agatha Christie and Dorothy L. Sayers, the story ended with one criminal fingered by the detective. Everyone else turned out to be innocent. Order was restored. It was as if the writers were saying, Don’t worry about what you read in the newspapers; everything can be fixed and only a small minority are making the trouble.

In my Palestinian crime novels, the opposite is true. Everyone’s guilty. Tat’s the reality I found in Palestinian society, as disaster befell it in the last decade – an intifada, a civil war, and now a horrible stand-off between rival factions. Not any one person’s fault.

I believe that’s a better reflection of the world in which we live. My novels are entertainments, but they aren’t layered with the conservative perspective of the “Golden Age.” I don’t want readers to think that there’s nothing wrong out there, so long as the detective nabs the sole bad guy in the library.

Crime novels today are grittier than the work of Christie. They tend to be closer to the atmosphere of Raymond Chandler, who wrote that the Golden Age stories “really get me down.” But the Chandler ethos of a lone knight facing an utterly corrupt world is largely ignored.

That’s why there are so many novels these days about pedophiles and psychopaths. Such characters are beyond the pale of behavior in which we could imagine ourselves participating. To commit a crime in such novels is to mark oneself out as a deviant. As soon as the deviant is nabbed, the society can go back into its usual calm manner.

I think this is why Scandinavian crime novels have been so popular. Readers like the fact that, while the detective wrestles with the psycho, the society depicted is clearly not so very flawed. As soon as the psycho is nabbed, Sweden will return to its pleasant, polite way of life—something that’s easier to envisage than it would be in a novel set in, say, Bangkok or Gaza. Even in his recent novel, “The Worried Man,” Henning Mankell describes his detective as being no more than “worried about the direction of Swedish society.”

Worried! Can you imagine Omar Yussef, my Palestinian sleuth, being no more than worried? He lives in a society that’s engulfed in disaster. He knows everything’s going to hell and he’s aware that nabbing a single bad guy won’t change that.

The golden age method ought to have been overtaken by reality in a post-Holocaust age. Hannah Arendt wrote of the banality of evil, meaning that people don’t choose good or bad, they just go along. We’d like to see bad guys as pure evil, deciding firmly to commit horrible acts, while the truth of the Holocaust and many other dreadful events is that people are much more likely to operate in a kind of malleable denial.

It’s a vital insight. Yet I find most crime novels are written as though Hitler never happened—as if one wicked man can be blamed for what millions of others simply went along with.

Read the rest of this post on my blog The Man of Twists and Turns.

Published on September 09, 2010 02:19

•

Tags:

agatha-christie, crime-fiction, detective-stories, dorothy-l-sayers, hannah-arendt, henning-mankell, hitler, holocaust, intifada, nordic-crime, omar-yussef, palestine, palestinian, raymond-chandler, the-samaritan-s-secret

Corrupt online reviews

Eleanor Roosevelt said that no one can make you feel bad, except yourself. I live by that rule. Particularly when it comes to reviews. And double-particularly when it comes to online reviews.

Eleanor Roosevelt said that no one can make you feel bad, except yourself. I live by that rule. Particularly when it comes to reviews. And double-particularly when it comes to online reviews.A recent Cornell University study found that 85 percent of amazon.com’s “top reviewers” had received free gifts from vendors. And 78 percent had reviewed the products. The “top reviewers” often strayed far from their expertise, if they even have one, boosting their productivity with reviews of minor domestic items so that they would maintain their “top reviewer” status and continue to receive free stuff.

It’s a corrupt system. Well, I live in the Middle East and I’ve become accustomed to corruption. So why have I had to bring Mrs. Roosevelt into the equation?

Because the corruption touches me personally, as it does every writer. Take the Amazon Vine program, which is mentioned in the Cornell study. As I understand it, Vine allows “top reviewers” to choose from a list of books, which they then receive free from the publisher on the understanding that they’ll write a review.

The publisher wants to participate because the number of reviews (as well as the quality of the reviews) seems to be part of amazon.com’s secret ranking system.

The problem appears to me to be that there’s a big difference between electing to pay for a book you want to read and clicking on a list of books you can receive free – and there’s likely to be just as big a difference in the kind of review you write.

Read the rest of this post on my blog The Man of Twists and Turns.

Published on September 02, 2011 00:19

•

Tags:

amazon-co-uk, amazon-com, cornell-university, eleanor-roosevelt, internet, online-reviews, reviews, the-samaritan-s-secret