Matt Rees's Blog - Posts Tagged "nonfiction"

Whingers and Warm Guns: Happy-Guru Eric Weiner's Writing Life

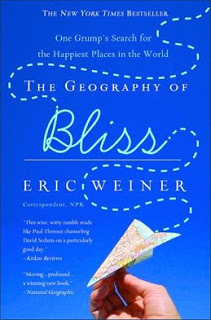

What’s happiness? A large income, Jane Austen said. Absolute ignorance, according to the delightfully morbid Grahame Greene. Or John Lennon’s less delightfully morbid warm gun. Whatever else it is, happiness is done to death. But where it is? That’s something new. The genius of Eric Weiner’s New York Times bestseller “The Geography of Bliss: One Grump’s Search for the Happiest Places in the World” is to change the way of searching for happiness. Instead of looking for ways to make himself happy (the typically American individualistic approach to joy), he went out to find places where other people were happy. That way the former NPR correspondent (I got to know him when he was Mideast bureau chief, but he was based in India, too, for a time) was able to identify broader characteristics of a society that create happiness. He found, of course, that being Swiss helps (they trust everyone around them and therefore don’t have to worry and watch their backs). Being Moldovan on the other hand definitely doesn’t help -- everyone cheats, nothing's fair = miserable place. On his journey Eric also ditched email. But he broke that rule for the sake of my blog, and I’m glad he did.

How long did it take you to get published?

It took me three weeks to find an agent and publisher. It took twelve years for me to settle on an idea that I was passionate about.

Would you recommend any books on writing?

No. I think the best way to learn to write is to write. Reading (everything and anything) helps, too. So does coffee.

What’s a typical writing day?

I wake up bright and early, and by 8:00 a.m. settle into my office. Then I check my e-mail. Then I check Facebook. Then I check a few of my favorite blogs. Then I break for lunch. Usuallly, after lunch, I will do some actual writing before calling it a day.

Plug your latest book. What’s it about? Why’s it so great?

You're asking a writer to plug his own work? Okay, if you insist. My book, The Geography of Bliss, is brilliant because it takes a fairly tried subject, happiness, and gives it a new twist. Most happiness books focus on the what of happiness; I was interested in the where. Which are the world's happiest countries and what can we learn from them? And--did I mention?--the writing is brilliant! Funny and serious at the same time. I would highly recommend it. Really.

How much of what you do is:

a) formula dictated by the genre within which you write?

b) formula you developed yourself and stuck with?

c) as close to complete originality as it’s possible to get each time?

Mainly b), I think, with a smattering of c). My genre, broadly speaking, is travelogue. It is an odd, self-loathing genre. Many of the great travel writers don't like to be called travel writers. I think that's because travel writing sounds fluffy and inconsequential. At least bad travel writing is like that. Good travel writing is simply good writing that happens to use place as its main construct. In my work, I try to fashion a slightly new genre, the travelogue of ideas. In that sense, my book isn't really travel book at all. It's a book about the nature of happiness that uses geography as a way to get at this mystery.

Where is your favorite place to write?

I like coffee shops. The background din, oddly, helps me focus. After a while, though, I get antsy and feel the need to move. I might write in two or three different places in a single day. After all, I am a travel writer. Place matters.

Who is your favorite travel writer?

Jan Morris. She can get to the heart of a place in a few sentences. She is opinionated, but not obnoxiously so. She puts herself in her writing but never gets in the way of a good story. And she can be funny in all the right places.

What do you do if you are stuck?

I drink more coffee. If that doesn't work, (and it usually doesn't) I go for a walk. If that doesn't work (and it usually doesn't) I read what I have written aloud. I tend to write for the ear, and reading aloud can help me regain my rhythm. Also, I recently discovered a wine called "Writer's Block." It's a very nice Zinfandel.

What do you read for pleasure?

I like big fat books that tackle big fat topics. I'm currently reading Peter Watson's Ideas; A History of Thought and Invention from Fire to Freud. It's easily 800 pages. I'm still in the fire bit.

How much research is involved in each of your books?

An awful lot. For The Geography of Bliss, I read everything I could get my hands on about happiness, from Aristotle to Marty Seligmen, the poo-bah of the "science of happiness." I camped out at a university library for weeks on end. For a while, I was concerned that I was over-researching, but now I dont' think there is such a thing. Many morsels from my research made their way into the final manuscript.

What’s your experience with being translated?

My book has been translated into 13 languages, The publishers send me copies, which is nice. I can't understand a word of them,. for all I know they did a terrible job of translating. But they look nice on my bookshelf. Especially the Korean edition. Very colorful.

Do you live entirely off your writing?

I do make a living off my writing. I consider myself very fortunate.

How many books did you write before you were published?

This is my first one. Non-fiction, though, is a lot easier to get published than fiction.

What’s the strangest thing that happened to you on a book tour?

I had just completed an interview with a radio station in Portland, Oregon, when the interviewer said, "That was really great, Do you want to smoke some weed?" It's true. I might have taken him up on it, but I had a book reading in a couple of hours, so I politely declined.

What’s your weirdest idea for a book you’ll never get to publish?

I'd like to write a travel book about time travel. I would go back in time to an age when there still were undiscovered places to explore and write about them. I'd also buy some choice real estate in Manhattan. Then I'd travel back to the present and live large.

Published on June 10, 2009 01:11

•

Tags:

east, eric, happiness, interviews, journalism, life, literature, middle, nonfiction, weiner, writing

Review: The thriller that reminds us why Euro politics matter

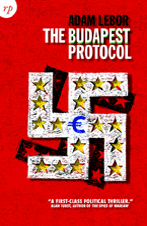

The Budapest Protocol, by Adam Lebor

(Reportage Press)

Sometimes a journalist comes across something so powerful that it seems bigger than the project he’s researching. Usually it’s put aside to serve as the basis for a future project, a magazine article or another nonfiction book.

Sometimes it takes such a grip on the writer’s imagination that there’s only one way to go. The novel. I know, because it’s how I turned from Middle East correspondent to the author of Palestinian crime fiction. Journalism seemed so limited by comparison, so unlikely to grab people and tell them “Pay attention, this really matters” the way a novel can.

That’s what happened to Adam Lebor in 1996 when he was researching his acclaimed “Hitler’s Secret Bankers: How Switzerland Profited from Nazi Genocide.” He stumbled upon a World War II intelligence dossier addressed to the US Secretary of State. It detailed a French agent’s report on German contingency plans for the economic takeover of Europe, should the Third Reich fail.

Lebor asked himself the question: what if the industrialists who intended to found this Fourth “economic” Reich had tried to do so, after the war? What if they had succeeded? (“What if,” as Stephen King notes in his “On Writing,” is the best place from which to start a thriller.)

From his vantage point as a correspondent based in Budapest, Lebor was able to see the massive inroads amounting more or less to takeover of post-Soviet economies by German and Austrian conglomerates. Add to that the growing centralization of the European Union and the introduction of its single currency forcing the economies of most of Europe to toe a single line, and you start to see why the Red House Report gripped him so.

The result is the chillingly real thriller “The Budapest Protocol,” published in the UK this month.

Alex Farkas, a local journalist, uncovers the economic conspiracy, which – as the novel unfolds – is focused on the election campaign of one of the conspirators as President of Europe (a post that many Brussels types would gladly see become reality). Farkas discovers plans for a new Holocaust against the Gypsies, which with the rise in these poor economic days of a neo-Nazi right-wing in Hungary is another of the novel’s moments of eerie realism.

What really drives Farkas, though, is the sinister murder of his grandfather, a survivor of the Budapest ghetto and a former dissident. That gives the novel the personal underpinning that elevates it above pure conspiracy theory. In fact, it makes it a first-rate thriller comparable to Robert Harris’s “Fatherland.” The novel reminds us that the politics of Europe remains more charged than the dull image the Brussels technocrats have lulled us into.

I’ll bet you’re sorry now you didn’t vote three weeks ago in the Euro elections. You will be after you read this novel.

Published on June 21, 2009 05:21

•

Tags:

budapest, crime, department, eastern, europe, fiction, futuristic, germany, hungary, jews, journalism, nonfiction, reviews, state, thrillers

Hot Reading in East Jerusalem!

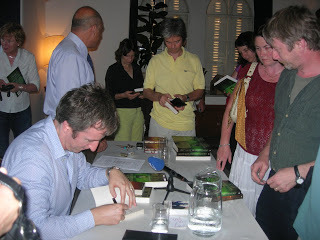

This weekend I was the guest of Munther Fahmi, who runs the excellent bookshop at the American Colony Hotel in East Jerusalem, for a reading from my newest Palestinian crime novel THE SAMARITAN'S SECRET. Munther and I have been scheming for some time to organize an event, so it was great to finally get it together.

I knew it'd be an interesting crowd at the Colony, which manages to be something like neutral ground (although many Israelis might dispute that) in Jerusalem. There were foreign journalists and diplomats, Israelis and Palestinians among the sizeable crowd, including some old friends I haven't seen for some time. Oh, and tourists, too -- a rare species since the intifada, but I signed for visitors from Berlin and Seattle, Ireland and Serbia.

I was also delighted that one of the people on whom I based the character of a World Bank worker in THE SAMARITAN'S SECRET happened to be staying at the Colony this weekend. I was able to give him the news that I'd turned him into a woman and changed his employer. He seemed pleased with both alterations, and I hope he enjoys the book.

I've edited the photos so that you can't see how hot it became in the room. By the time I was signing the books at the end I was rather inelegantly dripping with sweat. The alternative, of course, was the honking of passing Arab wedding convoys and, as antiglobalization activist Naomi Klein discovered when the windows were opened to let in some air for her reading immediately after mine, the evening call to prayers by the muezzin at the mosque next door. (It's the Mosque of Sheikh Jarrah, named after Saladin's doctor, whose tomb it houses.)

To get on Munther's mailing list for future readings at his excellent bookshop, write to him at bookshopat@gmail.com.

Published on June 28, 2009 03:05

•

Tags:

appearances, book, doctine, globalization, ireland, islam, israel, jerusalem, klein, naomi, nonfiction, omar, palestine, palestinians, samaritan-s, samaritans, secret, shock, tour, yussef

Culture and harshness in Central Europe: Adam Lebor's Writing Life

Political writing at its best highlights the unexpected changes in parts of our world that are hidden to us. That’s true of writing about the corridors of power in our own capital cities, but it’s even more of a factor for a writer like Adam Lebor whose work – fiction and nonfiction – has captured the dynamism and double-dealing of Central Europe, in particular. Because I live in the Middle East while he lives in Budapest, Lebor first came to my attention with his wonderful “biography” of Jaffa, the ancient port city on the Mediterranean coast, “City of Oranges: Arabs and Jews in Jaffa.” It was a masterful stroke to profile this town, rather than Jerusalem or even Tel Aviv, which tend to attract the attention of writers more readily than a historic city that’s now a slum filling with liberal yuppies. It shouldn’t have surprised me, then, that Lebor’s new novel The Budapest Protocol, which I reviewed recently, would take an issue that many think of as boring and bureaucratic – the expansion of the European Union – and make it immediate and vital, linking it to the demons of Europe’s past through Nazism and genocide. The novel is firmly in the tradition of great British writers like Eric Ambler, Graham Greene, and John LeCarre. Like them, Lebor knows that Central Europe’s cultured side comes with an accompanying harshness that makes for great drama.

How long did it take you to get published?

My first non-fiction book, ‘A Heart Turned East’, about Muslim minorities in Europe and the United States, was published in 1998 by Little, Brown, UK. It was commissioned so was published a few months after I wrote it. That was a fairly straightforward process. Since then I have written another five non-fiction books, all of which were commissioned.

Fiction, however, was a very different story. I first started writing the book that would become The Budapest Protocol in Paris in the winter of 1997. It was rejected by numerous publishers before I finally found one, Reportage Press, that would actually spend the time to tell me how to fix it. I always knew I needed the attention of a good editor, but apparently most publishers nowadays expect a perfectly formed novel to land on their desks, which is ridiculous.

Would you recommend any books on writing?

A search on amazon.co.uk for ‘writing a novel’ brings up 20,625 results. Most of the authors of these books are not well know novelists, because successful novelists are writing novels, not books about how to. That said, I have found ‘The First Five Pages’, by Noah Lukeman, very useful. Lukeman is a well-known American agent, and the book is full of good advice, from a commercial viewpoint. I would recommend it for anyone who is serious about getting published. I also like ‘Writing A Novel’ by John Osborne, which is enjoyably cantankerous but full of good advice.

What’s a typical writing day?

Breakfast with the Today programme on my Evoke internet radio, invaluable for keeping in touch when you live abroad - I am based in Budapest. Spend morning probably doing journalism or admin. Usually the muse arrives after lunch, and a good writing session will go from about 3pm to nine or ten at night. If it’s really flowing I will wake up in the morning with a plot solved or idea for a chapter plan that somehow my subconscious has sorted out while I am asleep and then I am straight back in the book.

Plug your latest book. What’s it about? Why’s it so great?

The Budapest Protocol is a conspiracy thriller that was inspired by a real American intelligence document from 1944. The document, known as the Red House Report, is an account of a secret meeting of Nazi industrialists in the Maison Rouge hotel, Strasbourg, where they planned for the Fourth Reich, which would be an economic imperium not a military one. That was the inspiration - I then used my twenty years reporting experience in eastern Europe to work out how that might actually happen. There is also a love story with several sexy, difficult girls and atmospheric scene setting in present day Budapest.

How much of what you do is formula dictated by the genre within which you write?

Thrillers are to some extent quite formulaic. The hero needs inner conflict to drive his outer battle with larger sinister forces. He needs to face and overcome repeated obstacles, each time getting in more and more danger. The trick is use the formula to make the structure work while making the setting, atmosphere and narrative drive powerful enough. Alan Furst, the master, gave me some advice: “Start with a murder and make sure the boy gets the girl” which was very useful.

What’s your favorite sentence in all literature, and why?

“Heshel was watching him through the window of the car and smiled thinly as their eyes met. Here is the world, said the smile, and here we are in it.” A line from my favorite book, Dark Star, by Alan Furst. Dark Star is an espionage thriller set in late 1930s Europe. That sentence is subtle, telling, and somehow opens a world of the imagination.

What’s the best descriptive image in all literature?

It was a bright cold day in April and the clocks were striking thirteen.

Who’s the greatest stylist currently writing?

Alan Furst. Less is more.

Who’s the greatest plotter currently writing?

David Ignatius, author of Body of Lies and The Increment. I would also add Stieg Larson, who sadly is not writing any more.

How much research is involved in each of your books?

The Budapest Protocol did not demand any specific research as I have covered this region for twenty years. My non-fiction books, like ‘City of Oranges: Arabs and Jews in Jaffa’ about Jewish and Arab families in the ancient port demanded many weeks of research, hours of interviews and gaining the trust of the families.

Where’d you get the idea for your main character?

The fact that he is a foreign correspondent, who lives in Budapest, who is obsessed with sinister conspiracies and who is entangled with beguiling but unsuitable women and whose first name is four letters beginning with ‘A’ is entirely coincidental.

What’s your experience with being translated?

Fine. I have been translated into eight languages, but I don’t really check what they have done to the book, even in languages I know.

Do you live entirely off your writing? How many books did you write before could make a living at it?

Now, yes. But that is combined with journalism for big papers like The Times, Economist etc. I think it would be very difficult just to live off books, and I like the change of pace with journalism. I value my connection with The Times, it opens doors and my assignments give me ideas for books and characters.

What’s the strangest thing that happened to you on a book tour?

I suppose it’s probably not that strange and happens to other authors but I was amazed that after two sell out events at the Edinburgh book festival with about 180 people in the room I only sold a handful of books. Why pay eight pounds to watch the author when you can buy the book for that?

What’s your weirdest idea for a book you’ll never get to publish?

I cannot reveal that as it’s such a good idea it may yet hit the shelves one day!

Poets central to Palestinian culture

My favorite Palestinian poet is Taha Muhammad Ali, a quietly bumbling presence when he reads his poems, but a deceptively intelligent writer. The warmth and intelligence of Taha’s readings drove Adina Hoffman, a Jerusalem-based writer, to plan a biography of the poet (“My Happiness Bears No Relation to Happiness: A Poet’s Life in the Palestinian Century”, published this April by Yale University Press). Only then did she discover that, despite all the ink spilled on the Palestinian issue over the years, no one had ever written a biography of any Palestinian poet.

So she expanded the book. Using Taha as the central figure, she constructed the intersecting life stories of writers as diverse as Mahmoud Darwish, the "national" poet whose death last year prompted weepy editorials around the world, and Rashid Hussein, the most original and tortured of them, who died alone and drunk in New York 30 years ago.

Hoffman’s book is a way for readers to get around the usual stereotypes of the Palestinians as they’re portrayed in the cliches of their political struggle. She looks at the fascinating day to day, emotional history of this troubled people as told through their dynamic poetic culture.

Here’s a brief interview with Hoffman I conducted last week:

Matt: Did it surprise you there was no biography of any Palestinian poet?

Adina: It did surprise me, but then again maybe it shouldn’t be so startling. I write in the book about the various challenges of composing the biography of a Palestinian subject—and high on that list is the lack of a Palestinian archive, or archives. Many of the writers (Taha Muhammad Ali and Mahmoud Darwish included) come from peasant backgrounds, and that peasant culture relied on the oral rather than the written record. And the little that may have been written down was destroyed in 1948. So I had to rely on a combination of interviews and British and Israeli archives (which were essential to my work, though the perspective presented there is obviously not Palestinian), as well as photos and books on a hundred different related subjects.

So it is, in a way, a luxurious genre: you can’t just pick up a pen and paper and write a biography like this. You need to have access to these archives and books and photographs as well as access to various interview subjects. A writer sitting in Beirut or even Nablus would have a harder time simply getting to these sources—whether because of checkpoints and borders or because the Israelis might not let them in. Meanwhile, those who might have access to the archives might not have the various languages required to make sense of them, or the desire to write about Palestinian culture… and so on and on.

Matt: With my Palestinian crime novels, I’ve tried to write about the real Palestinians as I’ve come to know them over the years, rather than the stereotypes with which they’re portrayed in journalism. Were you trying to do something similar?

Adina: I do agree that one can get a different idea of Palestinians as people through the history of their poets. First of all, because poetry and poets occupy such an essential role in Palestinian society: throughout much of the last century, poetry has served as one of the most important means of political and social expression for the Palestinian people—and the poets who’ve given voice to that impulse are central to the culture. But I was also interested in writing about the world that surrounded these poets and that inspired them to write. In Taha’s case, much of his poetry is grounded in his village, Saffuriyya, which was destroyed in 1948. The whole first part of my book is devoted to trying to conjure that village on the page. It’s not just about the destruction of that village, in other words; it’s also about the very rich and complicated life that existed there before ’48.

So much of the news coverage of the Palestinian “story” winds up treating them as a monolithic, basically faceless group—whether a group of terrorists or a group of downtrodden victims. I wanted to offer a view of Palestinian life that depicted as precisely and deeply as possible the full human range of feeling and complexity that exist in that culture, as in any culture. To put it more simply, I didn’t treat the Palestinians in my book as representatives of anything but themselves, as a group of individual human beings.

Matt: Anyone who’s written about the Palestinians knows that it can be a minefield, particularly when you face the public on a book tour. You’ve been in the US recently to promote “My Happiness Bears No Relation to Happiness.” What kind of response do you find there?

Adina: Apart from one or two predictable knee-jerk responses, I’ve been very pleasantly surprised by the openness of readers to the book. People seem quite eager to read about Palestinian life and culture in a way that gets past the standard version that’s put forth in the media. And on top of that, I think they’re just drawn to the incredible poignancy and richness of Taha’s story—and the story of so many of the people his life has intersected with over the years.

Published on June 30, 2009 23:52

•

Tags:

east, interviews, israel, life, middle, nonfiction, palestine, poetry, reviews, writing

Photos of the Jerusalem you don't read about in the newspaper

My friend Ilan Mizrahi has published a wonderful book of his photos about Jerusalem -- not the conventional Jerusalem of suicide bombs and the Dome of the Rock and praying Hassids (though he covers that, too). Ilan, who was born just down the road from where I now live and is as "Jerusalem" as they come, aims to capture a side of the city populated by the poor, the drug abusers, the beggars: the scavengers who make it a real place, one that's more interesting than anything you'd ever imagine from the cliched nuthouse of the tv news. My favorite is of a man playing violin on the street for small change, while another man urinates furtively against the wall behind him. Look at some of Ilan's photos here. Ilan also asked me to write an introduction to the book. Here it is:

Jerusalem is a rumor, fed by the whispers of centuries, until its echo returns distorted from its tittle-tattle travels, unrecognizable to those who live in it. Like all rumors, it is unreliable and somehow more broadly accepted than the reality.

I arrived in 1996, drawn by my relationship with a woman, rather than any particular fascination with Jerusalem. Of course, I had heard the rumors like everyone else; they crept out from the Bible and the histories of Rome and of Islam, on through my two great-uncles, who rode into town with Britain’s Imperial Camel Corps in 1917. But I came with few preconceptions, and that’s how I stayed. Though my business at first was the news, I was under no illusions about the uselessness of newspaper and magazine formulas for unveiling the truth of a place. I tried to travel the neighborhoods of Jerusalem with an anthropologist’s eye. It turned out I was attempting, as a writer, to do just what Ilan Mizrahi has been able to do as a photographer.

When I arrived, journalists were busy writing about the dull mechanics of the Oslo peace process. Lots of stories about the first Palestinian beer, the first Palestinian Olympic team, Palestine’s acceptance into FIFA, and the first joint patrols between Israeli and Palestinian soldiers. None of these developments amounted to much in the end, except perhaps the beer, but foreigners were so preoccupied with these pointless milestones that they were slow to see the danger signs. When I joined Time as Jerusalem bureau chief in 2000, the magazine’s editors had been considering hiring a business writer, because they believed that peace was on the way and that Israel’s high-tech industry would become the center of the story. Then came the intifada. Which only goes to show how little editors know.

I wasn’t as surprised as many by the violence which engulfed the second half of the period covered by Ilan Mizrahi’s book. One morning in 1998, I awoke in my Abu Tor apartment to discover 300 East Jerusalem Palestinians protesting on my street, where one of their compatriots had been stabbed early that morning. It wasn’t the fact that they turned out to chant and throw their fists in the air that shocked me, but that ready and waiting they had a massive Palestinian flag, five meters by three, which they had draped over a wall. This was supposed to be a neighborhood where the Arab residents weren’t militant and yet this flag materialized. But I heard something else in their cry, choking them less with politics than with the dryness of the old desert traditions of blood feud. So it was no surprise to me four years later when a Jewish woman was stabbed in the woods abutting the same street.

Since then, the Jerusalem of the newspapers has been the realm of endless suicide bombs and clichés about an “intractable conflict.” But the intifada revealed so much more, if you only looked. In 2002, 45 percent of small businesses in Jerusalem went bankrupt. That, in a city already stricken by some of the worst poverty in Israel. A city with a Palestinian refugee camp within its municipal boundaries, and another “camp,” Mahaneh Yehuda, where junkies shoot up at night.

When I came to write my nonfiction account of life here, Cain’s Field, I went to the ultra-Orthodox neighborhoods around Mea She’arim to write about the conflict between the burgeoning religious population and the old inhabitants, mostly from Morocco, being shoved out because they weren’t religious enough. As I walked through these streets, I noticed that schoolchildren stopped to stare suspiciously at me. I felt more foreign than I’ve ever done wandering a Gaza refugee camp. To me it was an important lesson about Jerusalem: its alienness comes to you when you least expect it. The sights and sounds to which you’ve been attuned all your life -- the Bible, the news, poetry and art -- can inspire, so long as you let them. With repetition, they dwindle into inflated half-truths for which you feel contempt or anger or boredom. But in the places where you’d expect Jerusalem to be drab and rotting, the places which aren’t the subject of scripture or famous songs, there you find the timeless moments of enlightenment. There, the city is no longer a whispered rumor. Instead, it speaks to you, loudly, berates you, until you’re forced to acknowledge that it isn’t what you thought it was. It never will be.

Jerusalem is a rumor, fed by the whispers of centuries, until its echo returns distorted from its tittle-tattle travels, unrecognizable to those who live in it. Like all rumors, it is unreliable and somehow more broadly accepted than the reality.

I arrived in 1996, drawn by my relationship with a woman, rather than any particular fascination with Jerusalem. Of course, I had heard the rumors like everyone else; they crept out from the Bible and the histories of Rome and of Islam, on through my two great-uncles, who rode into town with Britain’s Imperial Camel Corps in 1917. But I came with few preconceptions, and that’s how I stayed. Though my business at first was the news, I was under no illusions about the uselessness of newspaper and magazine formulas for unveiling the truth of a place. I tried to travel the neighborhoods of Jerusalem with an anthropologist’s eye. It turned out I was attempting, as a writer, to do just what Ilan Mizrahi has been able to do as a photographer.

When I arrived, journalists were busy writing about the dull mechanics of the Oslo peace process. Lots of stories about the first Palestinian beer, the first Palestinian Olympic team, Palestine’s acceptance into FIFA, and the first joint patrols between Israeli and Palestinian soldiers. None of these developments amounted to much in the end, except perhaps the beer, but foreigners were so preoccupied with these pointless milestones that they were slow to see the danger signs. When I joined Time as Jerusalem bureau chief in 2000, the magazine’s editors had been considering hiring a business writer, because they believed that peace was on the way and that Israel’s high-tech industry would become the center of the story. Then came the intifada. Which only goes to show how little editors know.

I wasn’t as surprised as many by the violence which engulfed the second half of the period covered by Ilan Mizrahi’s book. One morning in 1998, I awoke in my Abu Tor apartment to discover 300 East Jerusalem Palestinians protesting on my street, where one of their compatriots had been stabbed early that morning. It wasn’t the fact that they turned out to chant and throw their fists in the air that shocked me, but that ready and waiting they had a massive Palestinian flag, five meters by three, which they had draped over a wall. This was supposed to be a neighborhood where the Arab residents weren’t militant and yet this flag materialized. But I heard something else in their cry, choking them less with politics than with the dryness of the old desert traditions of blood feud. So it was no surprise to me four years later when a Jewish woman was stabbed in the woods abutting the same street.

Since then, the Jerusalem of the newspapers has been the realm of endless suicide bombs and clichés about an “intractable conflict.” But the intifada revealed so much more, if you only looked. In 2002, 45 percent of small businesses in Jerusalem went bankrupt. That, in a city already stricken by some of the worst poverty in Israel. A city with a Palestinian refugee camp within its municipal boundaries, and another “camp,” Mahaneh Yehuda, where junkies shoot up at night.

When I came to write my nonfiction account of life here, Cain’s Field, I went to the ultra-Orthodox neighborhoods around Mea She’arim to write about the conflict between the burgeoning religious population and the old inhabitants, mostly from Morocco, being shoved out because they weren’t religious enough. As I walked through these streets, I noticed that schoolchildren stopped to stare suspiciously at me. I felt more foreign than I’ve ever done wandering a Gaza refugee camp. To me it was an important lesson about Jerusalem: its alienness comes to you when you least expect it. The sights and sounds to which you’ve been attuned all your life -- the Bible, the news, poetry and art -- can inspire, so long as you let them. With repetition, they dwindle into inflated half-truths for which you feel contempt or anger or boredom. But in the places where you’d expect Jerusalem to be drab and rotting, the places which aren’t the subject of scripture or famous songs, there you find the timeless moments of enlightenment. There, the city is no longer a whispered rumor. Instead, it speaks to you, loudly, berates you, until you’re forced to acknowledge that it isn’t what you thought it was. It never will be.

Published on July 02, 2009 23:28

•

Tags:

east, gaza, intifada, israel, jerusalem, jews, middle, nonfiction, palestine, palestinians, photojournalism

Acknowledge no one

Here's my latest post on the International Crime Authors Reality Check blog:

Authors are posturing, self-aggrandizing assholes. At least, that’s the conclusion I’ve reached after noting the trend for excessive “Acknowledgements” growing like mold over page on page of nonfiction books. These days they’re spreading their blight all over novels, too.

Here’s how I think it breaks down.

More than a few paragraphs of Acknowledgements in nonfiction: the author is trying to show how in-depth he went, how many experts he befriended, how much those experts and sources went out of their way to contribute to his work of genius. But it’s a sign of insecurity, a fear that the book itself won’t demonstrate any of those things.

More than a couple of lines in a novel (I don’t really approve even of that): a lonely soul who wants to reach out to his few remaining friends, or a journalist manqué who wants to prove that his work is grounded in reality by laying bare his research sources.

In both cases, it’s an exercise that’s of no use to a reader. In fact, it can turn readers against a writer. This reader, anyway.

The thanks to wife and kids which are the conclusion de rigeur of all Acknowledgments typically can be translated thus: “thank you for putting up with my utter and total absorption in my great work. I’m a genius and it took you lovely, lovely people to realize it and to make the sacrifices that give me the space to work.”

Take for example my university tutor. A delightful man. But in one of his many books, his acknowledgements ended with thanks to his wife for “keeping the black coffee coming” as he labored over his text late into the night. His wife was a major feminist literary theorist. I wondered what she thought of being cast as a good little woman. They’re since divorced, so perhaps I know now what she thought.

Among my foreign correspondent pals, there’s another element of weirdness to the Acknowledgments in their books.

First, you have to put in plenty of fellows with foreign names, so everyone will know that you got tight with the locals and didn’t get all your info from the US Embassy.

Second, you have to name all the other correspondents who hung out at parties with you. I’ve been named in the Acknowledgments of a number of books. In most cases I didn’t read the manuscript. Neither did I aid in the researching of the book. Maybe I shared a taxi with the fellow or cooked him dinner one night. I helped one of them get laid.

That gets me into their Acknowledgements pages?

Fiction Acknowledgements are even more troublesome. They started with writers thanking people who’d acted as sources. Let’s say a crime writer thanking a real-life detective who told him which donuts cops like best.

But now writers feel the need to thank their editors and their agents. Not me. My agent gets her percentage. That’s how she knows I love her. (Which I do.)

I met a good friend of mine at an Upper West Side diner in New York a couple of years ago. He’d just sent in the manuscript for his second book. It had taken him eight years to follow up on his prize-winning debut. He’d been awarded a number of fellowships in the meantime, but he was feeling pressured to add an Acknowledgements page with the names of the many people who’d contributed advice and support during that lengthy period.

“But in the end I wrote the damned book.” He stabbed at the bananas in his oatmeal with each syllable. “Just me.”

We settled on a brief, tasteful Acknowledgements in which he only thanked the universities and foundations that had given him shelter or money. Everyone else would have to make do with a thank-you note.

Why do I really dislike Acknowledgements? In fiction, in particular, I find there’s something juvenile about them. There’s a reason why rock bands fill their liner notes with chums they’d like to thank for letting them sleep on the floor, while fine artists don’t paste the names of their best buddies all over the gallery wall.

Then there’s the “luvviness” of it all. They start the music at the Oscars after 45 seconds of gushing from the winners. How many book Acknowledgements can you get through in that time these days?

Authors: If someone deserves your thanks so very much that you just can’t hold it in, just dedicate the book to them. Acknowledge no one.

Authors are posturing, self-aggrandizing assholes. At least, that’s the conclusion I’ve reached after noting the trend for excessive “Acknowledgements” growing like mold over page on page of nonfiction books. These days they’re spreading their blight all over novels, too.

Here’s how I think it breaks down.

More than a few paragraphs of Acknowledgements in nonfiction: the author is trying to show how in-depth he went, how many experts he befriended, how much those experts and sources went out of their way to contribute to his work of genius. But it’s a sign of insecurity, a fear that the book itself won’t demonstrate any of those things.

More than a couple of lines in a novel (I don’t really approve even of that): a lonely soul who wants to reach out to his few remaining friends, or a journalist manqué who wants to prove that his work is grounded in reality by laying bare his research sources.

In both cases, it’s an exercise that’s of no use to a reader. In fact, it can turn readers against a writer. This reader, anyway.

The thanks to wife and kids which are the conclusion de rigeur of all Acknowledgments typically can be translated thus: “thank you for putting up with my utter and total absorption in my great work. I’m a genius and it took you lovely, lovely people to realize it and to make the sacrifices that give me the space to work.”

Take for example my university tutor. A delightful man. But in one of his many books, his acknowledgements ended with thanks to his wife for “keeping the black coffee coming” as he labored over his text late into the night. His wife was a major feminist literary theorist. I wondered what she thought of being cast as a good little woman. They’re since divorced, so perhaps I know now what she thought.

Among my foreign correspondent pals, there’s another element of weirdness to the Acknowledgments in their books.

First, you have to put in plenty of fellows with foreign names, so everyone will know that you got tight with the locals and didn’t get all your info from the US Embassy.

Second, you have to name all the other correspondents who hung out at parties with you. I’ve been named in the Acknowledgments of a number of books. In most cases I didn’t read the manuscript. Neither did I aid in the researching of the book. Maybe I shared a taxi with the fellow or cooked him dinner one night. I helped one of them get laid.

That gets me into their Acknowledgements pages?

Fiction Acknowledgements are even more troublesome. They started with writers thanking people who’d acted as sources. Let’s say a crime writer thanking a real-life detective who told him which donuts cops like best.

But now writers feel the need to thank their editors and their agents. Not me. My agent gets her percentage. That’s how she knows I love her. (Which I do.)

I met a good friend of mine at an Upper West Side diner in New York a couple of years ago. He’d just sent in the manuscript for his second book. It had taken him eight years to follow up on his prize-winning debut. He’d been awarded a number of fellowships in the meantime, but he was feeling pressured to add an Acknowledgements page with the names of the many people who’d contributed advice and support during that lengthy period.

“But in the end I wrote the damned book.” He stabbed at the bananas in his oatmeal with each syllable. “Just me.”

We settled on a brief, tasteful Acknowledgements in which he only thanked the universities and foundations that had given him shelter or money. Everyone else would have to make do with a thank-you note.

Why do I really dislike Acknowledgements? In fiction, in particular, I find there’s something juvenile about them. There’s a reason why rock bands fill their liner notes with chums they’d like to thank for letting them sleep on the floor, while fine artists don’t paste the names of their best buddies all over the gallery wall.

Then there’s the “luvviness” of it all. They start the music at the Oscars after 45 seconds of gushing from the winners. How many book Acknowledgements can you get through in that time these days?

Authors: If someone deserves your thanks so very much that you just can’t hold it in, just dedicate the book to them. Acknowledge no one.

Published on September 03, 2009 05:36

•

Tags:

check, crime, fiction, international, journalism, literature, nonfiction, publishing, reality, writers

I Have Publishing Surrounded: John Higgs's Writing Life

Thomas Carlyle wrote that “A well-written life is almost as rare as a well-spent one.” There may be some debate as to whether Timothy Leary’s life was well-spent. However, his biography by John Higgs is one of the most well-written and compelling books you’ll ever come across. “I Have America Surrounded: The Life of Timothy Leary” is an alternative history of the turbulent times that made modern America. Though it’s nonfiction, it reads much like James Ellroy’s hardboiled fictionalizations of the duplicitous reality behind the 1960s and 1970s in the U.S. Once you read the book and read this interview with John Higgs, you’ll understand why he was so attracted to Leary, the scientist who saw LSD as the answer to many of society’s ills and who ended up being called the most dangerous man in America by the FBI. No, not for the drugs (though one can’t rule that out….) Rather because John, an experienced tv writer and producer, is a man who doesn’t accept the idea that things simply have to be the way they seem to others.

Do you live entirely off your writing? How many books did you write before you could make a living at it?

I don't see living entirely off writing as a realistic aspiration in the Twenty-First Century, if I'm honest. It is still possible, of course, but the publishing model is in such a state of flux that only a wild and reckless gambler would wed their future financial security to it. The most significant factor, in my view, is that the amount of writing available to the reader has increased exponentially, and a sizable percentage of that is free. That alone changes everything, and threatens the writer with smaller, more fragmented audiences at best, or obscurity at worst. However, the cultural gatekeepers are also becoming increasingly irrelevant and you no longer need permission to go out and find readers. I'm delighted by all this. I love eBook readers, Print on Demand, profit-share deals with publishers and all the rest. I can't imagine a more exciting time to be a writer.

It's not the best time to be in the publishing industry, of course, as it undergoes a slow-motion nervous breakdown. The industry operates at such a 19th Century pace that if you killed it, it wouldn’t notice for eighteen months and then it would take another year to actually get round to dying. But even so, everyone can see that major, unstoppable structural change is happening. I have a hunch that in a few years time the writer-agent-publisher relationship will be start to be replaced by a writer-manager model, with publishing, promotion and distribution farmed out on a project-by-project basis while the manager concentrates on building a long-term readership for the author.

I'm not sure that everybody is prepared to be realistic about the changes that are happening. The idea of ‘writing books’ as a profession rather than a vocation, interest or even hobby is a very romantic one and people cling to it. Writers get very angry at the idea that no-one wants them to write enough to actually give them money to do it. Painters and, to some extent, musicians and actors are generally more realistic about this than writers, and also more realistic about why they do what they do. There's no reason why writers should be above working for a living - the likes of Philip Larkin or T.S. Elliot were prepared to do so. I think a big part of this is because the idea of using writing as an excuse to lock yourself away and withdraw from the world can be very seductive.

Of course, I like money. I like people giving me money, and I especially like getting money for something that I have written. But I think the writer/reader relationship is much healthier now, now that the playing field has been leveled, and if that means authors need to hold down a day job then that's a fair price to pay.

What's a typical working day?

There's no such thing as a typical working day, just as there's no such thing as a typical person or a typical philosophy. My writing life consists mainly of trying to find little two-hour windows where I can sneak off and furiously type away, without anyone giving me a hard time for doing so. You can get a surprising amount done using this method.

Do you have a pain from childhood that compels you to write? If not, what does?

I don’t know what compels me to write, but I don’t think it’s pain from childhood. My current best guess is that I write about things in order to lose interest in them. It is those things that don’t make any sense that I have a problem with. My brain is unable to digest them and they stick around, endlessly being picked over and prodded. Writing about them is the only way I know of flushing these buggers away, leaving me clear headed and hopefully a little saner.

Other writers have other reasons for writing but I don’t claim to understand what they are. Consider writer’s block, for example; being unable to write because you have nothing that you need to say. This sounds terrific to me. Imagine all the things you could do with the time! Yet other writers insist writer's block is a terrible thing, so presumably I’m failing to understand something somewhere.

How many books did you write before you were published?

My first book was published, but then I'm a lucky beggar. That said, of course, most of the stuff I write is scrappy nonsense which is written entirely for myself and shoved away in a draw and forgotten about. Only occasionally does it amount to anything that would interest others enough to justify the process of editing, polishing and all the business stuff involved in getting it published. I'm pretty lazy and would be quite happy not to have to go through all that, but it is important to be read and to have the contents of your head peer reviewed from time to time.

Who is the greatest plotter currently writing?

I'd say Steven Moffat. TV writers tend to be better plotters than novelists or film writers – at least, the really good ones are. Novelists have too much freedom and screenwriters are too restricted by the amount of people involved and the compromises that are needed when so much money is at stake. TV writers are in a middle ground where they have to hold a general audience but can't rely on big budget spectacles, so they have to get good at either plot or character, and preferably both.

Who is the greatest stlyist currently writing?

I recently read an unpublishable novella called 'The Nabob of Bombasta' by Brian Barritt, the English beatnik who you might remember from my Timothy Leary biography. I can only describe it as like literary wasabi. It is so wild and extreme that taking a little between regular literature wipes clean your mental pallette and allows you to approach your next piece with a fresh, unprejudiced mind. It is way beyond obscene and unacceptable, but it is so good-hearted, absurd and funny that anyone who claims to be offended by it is probably lying, and probably lying to themselves. Brian quite happily describes it as utterly unpublishable yet I hear it will be published next year, on Valentine's Day. Look out for that one!

What's the weirdest idea for a book you'll never get to publish?

You can publish anything these days, no matter how weird. The only constraint is whether there is an audience big enough, or interested enough, to justify your time. But as for weirdest idea, I sometimes hanker to re-publish the Bible in wildly unsuitable fonts, to see if it retains any credibility. Who wouldn't want a copy of 'The Old Testament in Comic Sans'?

What's the best descriptive image in all of literature?

That's an easy one. The best descriptive image in all of literature - better than "He Wishes for the Cloths of Heaven" or "Rough winds do shake the darling buds of May" - is Douglas Adams' "The ships hung in the sky in much the same way that bricks don't."

Plug your latest book. What's it about? Why's it so great?

Christ no - where's the fun in that?

The Real Iraq War: Michael Anthony’s Writing Life

By now it’s no secret that the Iraq War has been a disillusioning experience for many of the U.S. servicemen sent there. The literature on the war has, so far, been mostly written by journalists. There’s plenty of it, and like most journalism it runs pretty mainstream and inoffensive, no matter how bloody the scenes depicted. But Michael Anthony, a veteran of the war, has a different perspective. His new book Mass Casualties: A Young Medic’s True Story of Death, Deception, and Dishonor in Iraq is the best account yet of a war that continues to cost lives and to sully the image of the democracy in whose name it was supposedly fought. It’s a subject I’ve thought about a great deal as I travel my corner of the Middle East and as I continue to encounter fighters – Israeli and Palestinian – who endure personal hardship and tormenting nightmares when they face the realities of war. So read the book. Meantime, here's Michael's Writing Life.

By now it’s no secret that the Iraq War has been a disillusioning experience for many of the U.S. servicemen sent there. The literature on the war has, so far, been mostly written by journalists. There’s plenty of it, and like most journalism it runs pretty mainstream and inoffensive, no matter how bloody the scenes depicted. But Michael Anthony, a veteran of the war, has a different perspective. His new book Mass Casualties: A Young Medic’s True Story of Death, Deception, and Dishonor in Iraq is the best account yet of a war that continues to cost lives and to sully the image of the democracy in whose name it was supposedly fought. It’s a subject I’ve thought about a great deal as I travel my corner of the Middle East and as I continue to encounter fighters – Israeli and Palestinian – who endure personal hardship and tormenting nightmares when they face the realities of war. So read the book. Meantime, here's Michael's Writing Life.How long did it take you to get published?

I started writing the book as soon as I returned home from Iraq. I wrote the first hundred pages in six months and then the last hundred pages in two days (for the first draft). I then spent several months editing and doing rewrites. In total, from starting to write until getting a book deal, it took one year (almost exactly).

Would you recommend any books on writing?

I’m sure there are some out there, but I’ve never read any books on writing. I can give you a few of my favorite books though; the ones that I place as the top tier of writing, and for me, I think reading books, with a great style and prose, can help your writing as well. My top books (not in any order): Atlas Shrugged, Catch 22, Catcher in the Rye, The Perks of Being a Wallflower.

What’s a typical writing day?

I usually spend my typical writing day, finding other things to do than write. I think part of the aspect of being a writer is having the discipline to actually sit down and write. I don’t write every day as most writers do, but when I do write, that’s all I do. For me, it’s not about quantity of time, but quality of time. I could write while doing laundry or watching television, but it wouldn’t be the same. When I do write, it’s all about the writing and nothing else, I throw myself into and sometimes I won’t shower or leave the house for days.

Plug your book. What’s it about? Why’s it so great?

My latest and first book is: Mass Casualties: A Young Medic’s True Story of Death, Deception, and Dishonor in Iraq. It is the true story of what goes on during war, and what went on over there. It’s not a pro war or anti war book, it’s simply a true war story. I think a lot of stories/movies/shows out there; paint this picture of the American Soldier as this romanticized heroic idea. What I wanted to do with my book was simply paint a picture of the American Soldier as a human. It goes back to the old saying: “I’d rather be hated for what I am, than loved for what I’m not.” If people really want to appreciate and support the troops, the least they can do is learn the real stories, and not just the ones they’re told by reporters or the military officials.

If you look at a majority of war books or movies out there, they all paint this perfect picture of war and its effects. For example, look at one of the long running war movie franchises: Rambo, starring Sylvester Stallone. Rambo goes off to war and comes home with severe post-traumatic stress disorder. Even with this PTSD, he still manages to be a hero, save a town or city from some disaster and at the end, still get the girl. But in reality, if a soldier comes home with severe PTSD, they kill themselves. End of movie, roll the credits.

The problem with romanticizing these soldiers and situations is that when they come home, no one understands what they went through and what it was really like. And because of this, today’s military has the highest suicide rates in thirty years. Since the Afghanistan war started, more active duty soldiers have killed themselves than have been injured or killed in Afghanistan—combined. This is why I think we need to give people the full picture of war, and not just the good stuff they want to know about.

Who’s the greatest stylist currently writing?

My current, favorite, contemporary writer is: Stephen Chbosky, author of: The Perks of Being a Wallflower. For me, I just loved everything about that book, from the idea of it, to the way it was written.

How much research was involved in your book?

The vast majority of my book was based on my journals in Iraq, and because of this, the research involved was minimal. All I had to do was convert my illegible sometimes chaotic journal entries, into readable prose.

What’s the best idea for marketing a book you can do yourself?

Tell everyone you know, or have ever known, and then tell them to tell everyone they know. I now think everyone in my high-school class knows I have a book in bookstores. Social Media is a great thing, and don’t be afraid to go out there and use it. Also, I think getting other authors to review and/or comment on your work. I was able to get over thirty well accomplished people to review, comment on, and endorse my work; from famous politicians, to famous historians, psychologists, veterans and authors.

How many books did you write before you were published?

When I was sixteen I had written three books and two movies; it then took me five years to realize I wanted to be a writer.

What’s your weirdest idea for a book you’ll never get to publish?

When I was younger, I once wrote a book from the perspective of a T-shirt. The book had a T-shirt as a main character and I followed him around and wrote about what he was thinking as the wearer of the shirt went around and did his daily duties.

Less about suicide bombers, more about suicides

Michael Anthony is the author of MASS CASUALTIES: A Young Medic’s True Story of Death, Deception and Dishonor in Iraq (Adams Media, October 2009). His book is drawn from his personal journals during the first year he spent serving in Iraq. You can read my interview with him here. In this guest post, he highlights an issue we all ought to give more thought.

President Obama recently stated that sending more troops into harm’s way in Afghanistan is a solemn decision—one that he would not rush. As a veteran, I find the decision to send troops into harm’s way without an effective military mental health program in place beyond solemn. It’s deeply disturbing. Keeping soldiers mentally fit should be as important as keeping them physically fit.

Since the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq started, nearly 2,000 active-service soldiers have killed themselves, according to a report by the San Antonio Express-News earlier this year. Even more alarming is the fact that every day, five active-duty service members attempt suicide. In the past eight years, that means up to 14,000 have felt their life is not worth living.

The government doesn’t want you to know this. In spring of 2008, CBS news journalist Armen Keteyian exposed a Veterans Administration cover-up of suicide stats. The reporting revealed that every day, eighteen veterans kill themselves and roughly 1,000 attempt suicide each month. The VA’s head of Mental Health had claimed there were only 790 attempts in all of 2007, a far cry from the reality.

Among all veterans, over the eight years we’ve been at war in the Middle East, the statistics point that roughly 50,000 have committed suicide, with upwards of 44,000 attempting suicide. These figures only represent data gathered since 2001; this has been an ongoing and persistent problem since Vietnam—and the numbers go up each day.

Recently, the Army made a big deal about giving $50 million to fund a five-year research project on military suicide. In their book, The Three Trillion Dollar War, Linda J. Bilmes and Nobel Prize-winning economist Joseph E. Stiglitz figured the cost of the Iraq war at $12 billion a month. That means we spend more than $16 million an hour. If you do the math, the $50 million that went to suicide research is what we spend every three hours in Iraq.

The day after Christmas this year will mark our 3,000th day at war. At this point, we’ve heard a lot about suicide bombers, but what about suicide? Regardless of anyone’s feelings about our involvement in Iraq and Afghanistan, these soldiers deserve much more than three hours of our time.

President Obama recently stated that sending more troops into harm’s way in Afghanistan is a solemn decision—one that he would not rush. As a veteran, I find the decision to send troops into harm’s way without an effective military mental health program in place beyond solemn. It’s deeply disturbing. Keeping soldiers mentally fit should be as important as keeping them physically fit.

Since the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq started, nearly 2,000 active-service soldiers have killed themselves, according to a report by the San Antonio Express-News earlier this year. Even more alarming is the fact that every day, five active-duty service members attempt suicide. In the past eight years, that means up to 14,000 have felt their life is not worth living.

The government doesn’t want you to know this. In spring of 2008, CBS news journalist Armen Keteyian exposed a Veterans Administration cover-up of suicide stats. The reporting revealed that every day, eighteen veterans kill themselves and roughly 1,000 attempt suicide each month. The VA’s head of Mental Health had claimed there were only 790 attempts in all of 2007, a far cry from the reality.

Among all veterans, over the eight years we’ve been at war in the Middle East, the statistics point that roughly 50,000 have committed suicide, with upwards of 44,000 attempting suicide. These figures only represent data gathered since 2001; this has been an ongoing and persistent problem since Vietnam—and the numbers go up each day.

Recently, the Army made a big deal about giving $50 million to fund a five-year research project on military suicide. In their book, The Three Trillion Dollar War, Linda J. Bilmes and Nobel Prize-winning economist Joseph E. Stiglitz figured the cost of the Iraq war at $12 billion a month. That means we spend more than $16 million an hour. If you do the math, the $50 million that went to suicide research is what we spend every three hours in Iraq.

The day after Christmas this year will mark our 3,000th day at war. At this point, we’ve heard a lot about suicide bombers, but what about suicide? Regardless of anyone’s feelings about our involvement in Iraq and Afghanistan, these soldiers deserve much more than three hours of our time.