Matt Rees's Blog - Posts Tagged "malta"

On Caravaggio’s Trail: Travelling to Research A NAME IN BLOOD

As I researched A Name in Blood, my novel of Caravaggio, I went all over Europe and North America, tracking Caravaggio's works and the places that touched his life. The period locations I visited gave me a flavour for Caravaggio’s life. In some cases, they gave me ideas for plot twists in the book.

Everywhere I found people fascinated with this most compelling of artists. On one of my sojourns in Rome, there was an exhibition devoted to Caravaggio's use of mirrors to project images (over which he painted, giving the vivid realistic feel people usually notice when they first see his work). He used his own head, probably in a convex mirror, to paint his "Medusa," which ended up in Florence at the Galleria Uffizi. The Rome exhibit made a nice mock up. Life size, as you see, though perhaps not as scary as a traveling author making a funny face.

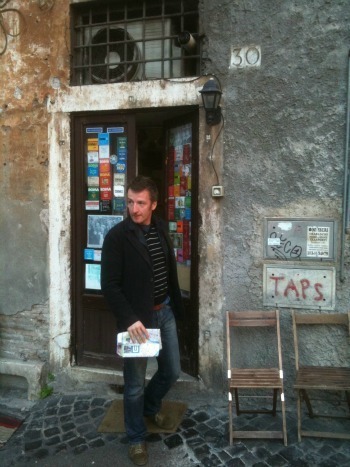

Caravaggio lived most of his time in Rome in the palaces of wealthy patrons. For a brief period, he rented this house (right) in a tiny street in Rome's historic center. Then he fell behind on the rent, lost the place, got drunk and went around to break his landlady's windows. I stood in the tiny alley imagining what it must have been like to be Madama Bruni, with a raging nutcase hurling rocks at her shutters from a yard away and bellowing that he was going to carve her up. Unfortunately I had to cut that incident out of A Name in Blood because, as with some other juicy moments in Caravaggio’s life, they were deeply revealing, but they didn’t drive my narrative forward.

Caravaggio’s model (and, I think, lover) Lena lived here (left). In the Via dei Greci. In the heart of what used to be the Ortaccio, or Evil Garden, where only whores and the very poor lived. And artists, of course. Both places are now very expensive spots in the middle of Rome’s tourist area. But they're still redolent of C's time. At night, they're dark and empty. Though not spooky. I never get spooked in Rome. I’m too damned happy there.

Rome was an important stop on my researches into period locations (as opposed to my more farflung journeys to the many galleries housing Caravaggio’s work), but Malta was in many ways the most compelling, because Caravaggio’s influence is still so considerable. Caravaggio is an important figure for its capital, Valletta, where he became a Knight of Malta and painted one of his masterpieces, The Beheading of Saint John for the city’s cathedral. Father John Critien (right) is the only Knight of Malta who currently lives in Castle Sant'Angelo on Valletta's harbor. C was imprisoned here, and made a dramatic escape. Father John and I spent a delightful afternoon examining all the spots where Caravaggio might've been held. Many think it was in a hole in the rock called the guva.

On to Naples I went. At left is the site of the Ceriglio Tavern, where Caravaggio was attacked on his way out. He got a scar, probably just to teach him a lesson rather than an attempt to kill him, and an injury to his eye, which can be seen in his last work, David with the Head of Goliath. I noticed that for much of the afternoon anyone leaving the Ceriglio and headed toward Caravaggio's digs at what’s now called the Palazzo Cellamare would be blinded by the sunlight. A good time for an attack.

My friend Ugo Somma, far right, showed me around Naples. Here he is examining the chapel of the Knights with a fellow named Rosario who works for the Knights of Malta in Naples. At first Rosario wouldn't let us look around the Knights' church. But when I told him he looked like Caravaggio, he relented and even introduced me to his sister...

At the Knights' Priory in Naples, these fellows were hanging around in the courtyard looking like mafia capos waiting to rub someone out. A non-Neapolitan had been named that morning as the new Prior. They were, as the Italians say, "arrabiati." Mad as hell. Their sullen expressions and taciturn demeanor gave me an idea for a plot twist in A Name in Blood….

My son became an aficionado of Caravaggio as the research went on. He visited many of the galleries and churches in Rome where Caravaggio’s paintings hang. When I was painting my own versions of Caravaggio’s Madonnas, I told him the woman was named Mary. He decided we had to call his new sister by that name, which we did (in the Welsh fashion, it’s spelled Mari.) His name being Cai, we dubbed him Cairavaggio.

One of my earliest memories is of a schoolteacher who had been in Naples with the British army in World War II. He wasn’t talkative, but one day he told me about a hunchback who had beckoned him to a garden and shown him the most beautiful sight he had ever seen: the perfect view over the Bay of Naples. Somehow that simple recollection of beauty by an old man, unfolded in an uncomplicated way to a small boy, brings tears to my eyes. I found the same beauty in Naples—alongside considerable depravity, too. They say, "See Naples and die." Unfortunately for Caravaggio, that's how it worked out, quite literally. Naples is magical, lively, putrid and beautiful. From the Spanish Palace looking at San Francesco, here's one moment when I thought: Matt, you lucky fellow, isn't "research" great?

Published on June 06, 2012 04:10

•

Tags:

a-name-in-blood, art, art-history, caravaggio, crime-fiction, historical-fiction, malta, naples, rome

Too Many Drugs: Following Caravaggio in Malta for A NAME IN BLOOD

I left Rome to continue my research for A Name in Blood, my Caravaggio novel which is released July 1 in the UK, in Malta. Caravaggio fled to the remote island off the coast of Africa and became (briefly) a member of the Knights of Malta. It was a strange trip for me, but the isolation and pure weirdness I felt there gave me important insights for the novel.

I left Rome to continue my research for A Name in Blood, my Caravaggio novel which is released July 1 in the UK, in Malta. Caravaggio fled to the remote island off the coast of Africa and became (briefly) a member of the Knights of Malta. It was a strange trip for me, but the isolation and pure weirdness I felt there gave me important insights for the novel.I spent December in Malta in a cheap hotel in a four-hundred-year-old building that was without heating and insulation, in a room where one of the windows didn’t close. I got sick. I took some drugs, staring across the harbor at the sheets of rain plummeting down on the Castel Sant’Angelo where Caravaggio was imprisoned for a time. It got damper in my room. I took too many drugs. I hallucinated, slept at unaccustomed hours and was awake when everyone else was in bed. I saw things that weren’t there. I drank far too many espressos at the Café Merisi, which takes Caravaggio’s family name and emblazons his face on the napkins, until I was as jittery as a June bug. A June bug with an overdose.

In this condition, I stood all day before The Beheading of Saint John, Caravaggio’s largest canvas and one of his most gruesome and disturbing. He showed John the Baptist collapsing, hands bound, on the floor of a dungeon, his executioner sawing his head away and a jailor gesturing for the severed head to be placed on a platter held by a young woman. It’s the only painting where Caravaggio signed his name. And he did it in a deep red, mingling with the blood spurting from the dying saint’s neck, giving me the title of my novel: A Name in Blood.

At night I wandered the narrow, deserted, windswept streets of Valletta’s Baroque center, weaving light-headed over the flagstones under the sad Christmas lights that rocked on the wind. Loudspeakers on the street lamps played cheesy carols. Alone as I was, I sang along, laughing to myself and feeling more than a little unhinged. In the alleys, I imagined Caravaggio here, knowing that men sought to kill him. I jogged giggling up the banks of steps that connect the streets along Valletta’s high ridges, as if I were fleeing. I panted in fear and slugged down some more drugs from the pocket of my raincoat and felt his horror of the dark.

I knew why Caravaggio had painted his figures emerging from the threatening shadows into a light so luminous that it glows straight through your skin and eyes and into the seat of your capacity for love, wherever that may be.

Stumbling down the steps toward my hotel above the gate where the Knights used to display the heads of Muslim pirates on spikes, I knew I was ready to write.

Published on June 07, 2012 01:15

•

Tags:

a-name-in-blood, art, art-history, caravaggio, crime-fiction, historical-fiction, malta, naples, research, rome

Behind the Book: Writing My Caravaggio Novel A NAME IN BLOOD

On the upper floor of the Museo Thyssen-Bornemisza in central Madrid, I wandered into a broad room where the masterpieces were arrayed like chocolates in a box. Just as with an assortment of sweets, I knew immediately and innately which one attracted me. I stepped into the arms of Caravaggio’s Saint Catherine of Alexandria. She still hasn’t let me go.

On the upper floor of the Museo Thyssen-Bornemisza in central Madrid, I wandered into a broad room where the masterpieces were arrayed like chocolates in a box. Just as with an assortment of sweets, I knew immediately and innately which one attracted me. I stepped into the arms of Caravaggio’s Saint Catherine of Alexandria. She still hasn’t let me go.I was in Madrid on a book tour for the Spanish translation of the first of my Palestinian crime novels. The Thyssen is just across the wide, busy Paseo del Prado from the immense museum of that name. It’s a building with two wings: a traditional classical palace in burnt sienna and pink stone; alongside a block of bright white louvered walls and angled blue-glass rooflights, like an old auto factory transported to a sci-fi future. I had no idea what awaited me inside. It was a novel.

The Caravaggio works I had previously seen in London and New York had impressed me. I was aware of the conventional summary of the stylistic revolution he wrought: to fill his canvasses with darkness and, with a strategically placed lantern, to bring the central action shining out of the shadows. That technique has been a major influence on filmmakers like Scorsese and almost every professional photographer, which is why Caravaggio’s four-hundred-year-old paintings look so modern. I knew something about his life too, though largely through the weird distortions and art-house tedium of Derek Jarman, having seen the British director’s Caravaggio film in college. As a writer, however, I’ve found a confluence of impressionability and idea lies behind every novel, so that only at one given time can you write a particular novel. A few years previously, I might’ve seen Saint Catherine, considered her for a moment, then moved on, as I had done when I saw Caravaggio’s The Supper at Emmaus in London’s National Gallery. But, for some reason, when I entered her room at the Thyssen and she spoke to me, I was listening.

I stayed in that room a long time. I couldn’t say quite how long. But it was at least an hour. The other paintings held my attention a matter of moments. I can’t remember them. (I’ve had similar experiences when I’ve traveled to see Caravaggio’s art around the world since then. No artist has such a capacity to make everything else in a gallery ignorable as Caravaggio has). In the Thyssen, I recall that the walls were of a beige rough fabric, a little like delicate sackcloth. The ceiling was white. Details as scant as you might retain from love-making. You might forget your mood or the immediate surroundings, but you’d have a clear picture of the way she looked at you or the feel of her hand on the back of your neck. Of Catherine, I remember everything. Even things that weren’t on the canvas.

The eyes of Caravaggio’s saint were possessive, grasping and sensual, clandestine and forbidden. For much of the time I was with her, we were alone. It felt as intimate as the languor after an act of love. There’s a question in that post-coital moment and Catherine asked it of me: Is this the last time? Will I see you again? Do you want to know more about me and where I come from?

Eventually I tried to leave the empty room. In her face I saw a plea. As if she wanted me to know that by leaving I would abandon her to her fate, represented by the spiked wheel on which she leaned (where the saint was tortured, before she was dispatched with the sword whose shaft she fondles.) What’s so compelling (and in his day was controversial) about Caravaggio is that he didn’t expect the saint’s suffering to be enough to keep you on her side. He gave her the sexual magnetism of Fillide Melandroni, the whore he used as his model.

The hold Caravaggio subsequently took on me amounted to what many people would call an obsession. I prefer not to use that term, because it implies a degree of madness and the inability to see when you’re mistaken about something. A writer needs to know when he’s gone wrong. Still, I traveled all over Europe and America to see Caravaggio’s works. I learned to paint with oils, to fight with a rapier. I grew a beard like the one Caravaggio sported just before his death at age 39. I did a few others things that paralleled the artist’s life and which were too intimate, shameful, or mystical to be recounted here. So, go ahead, call it an obsession.

After Madrid, my long road of research began with Peter Robb’s fabulous biography “M: The Man Who Became Caravaggio.” An Australian who lived a long time in southern Italy, Robb’s account of Caravaggio’s life is detailed in a non-academic way and deeply felt. He examines the mystery surrounding Caravaggio’s disappearance without prejudice, which earned Robb quite a deal of criticism from Caravaggio “scholars” when he published his book in 1998. The “accepted” version of Caravaggio’s demise is a tall tale of mistaken identity, a mad scamper along a malarial coastline, fever, death in a Tuscan convent and an unmarked grave. Academics tend to assume that considering anything other than this hashed-over version of Caravaggio’s death represents a foray into sensationalism, rather than simple curiosity about how this most dynamic of Italian artists simply vanished. (I had encountered a similar preference for the boring and quotidian in professors writing about Mozart’s death, while I researched the composer’s mysterious end for my novel Mozart’s Last Aria. Somehow academics seem committed to taking history’s dramatic events and making them appear as banal as another day in the faculty canteen, and they get inordinately angry with someone like me who decides to eat lunch off campus.)

It’s a considerable undertaking to write a novel about an artist whose works are dispersed around the world, whose pictorial skills you don’t share, and whose life was lived in such a distant time. But I didn’t think for a moment that I shouldn’t write the book. Well, okay, so it really was an obsession…

I traveled throughout Italy to see the places that touched Caravaggio’s life. In particular I spent a lot of time in the historic center of Rome, the neighborhoods around the Piazza Navona which are now the tourist heart of the ancient city. In Caravaggio’s day, this was the “Evil Garden,” where the Pope decreed the whores should live. Naturally, where there were whores, there were artists and trouble. In Rome, once more I found a communion with a Caravaggio painting. This time it was perhaps deeper even than the one I shared with Catherine. At the Galleria Borghese, I sneaked around the guards who usher on lingerers so newcomers may pile through the galleries built by Caravaggio’s patron Cardinal Scipione Borghese. I needed more time with the Madonna with the Serpent. This Madonna is based on a girl named Lena, who I made a major character in my novel. I wouldn’t even quibble to say I obsessed about her. I fell in love, and it was clear to me that Caravaggio couldn’t have painted her the way he did unless he had shared that emotion. Here is where some of the mystical aspects of my research come in. I won’t go into detail about them. I’ll only say that I feel as though I’ve met this girl Lena. Certainly, when I learned to paint with oils so as to be able to describe how Caravaggio worked, I painted Lena over and over.

From Rome, I went on to Naples, where Caravaggio took refuge. In the chapel of the Pio Monte della Misericordia, I stood before the great painting now known as Seven Works of Mercy, which is topped by another Lena Madonna (Caravaggio called it Our Lady of Mercy.) The noise and chaos of Naples’s narrow streets spilled through the door of the chapel, just as they had in Caravaggio’s day. I wondered at the force of personality and the drive to create that enabled him to paint this phenomenal work of devotion and love, while separated by a single door from a raucous crowd in which may have lurked the men who wanted to kill him (By the time he went to Naples, Caravaggio had a price on his head for a fatal duel.)

Dueling was another element of my research. I had to know how it felt to wield both a brush and a rapier. By coincidence (in my obsessive state, I sometimes thought it was fated), the Academy for Historical Fencing happens to be located in the town where I was born and where my parents live: Newport, South Wales, a former steel town with little apparent connection to historic chivalry. Nick Thomas, a Medieval and Renaissance sword enthusiast, started the Academy there and so I found myself driving up to Caerleon, the Newport suburb where the Romans once had a fortress, on a Friday night with my Dad, ready to do battle. Within moments of strapping on my chest protector and pushing down a visor tight over my big Celtic head, I found myself amazed at the balls it must have taken to duel with these five-feet-long swords without protective gear. The tip of my opponent’s blade mesmerized me. To fight, I’d have to ignore this point that—in Caravaggio’s circumstances—would’ve killed me in one thrust. It took some doing, I can tell you.

I journeyed on to Malta, where Caravaggio fled and became (briefly) a member of the Knights of Malta. I spent December there in a cheap hotel in a four-hundred-year-old building that was without heating and insulation, in a room where one of the windows didn’t close. I got sick. I took some drugs, staring across the harbor at the sheets of rain plummeting down on the Castel Sant’Angelo, where Caravaggio was imprisoned for a time. It got damper in my room. I took too many drugs. I hallucinated, slept at unaccustomed hours and was awake when everyone else was in bed. I saw things that weren’t there. In this condition, I stood all day before The Beheading of Saint John, Caravaggio’s largest canvas and one of his most gruesome and disturbing. It’s the painting where he signed his name—the only time he ever signed a work. And he did it in a deep red, mingling with the blood spurting from the dying saint’s neck, giving me the title of my novel. At night I wandered the narrow, deserted, windswept streets of Valletta’s Baroque center, weaving light-headed over the flagstones under the sad Christmas lights that rocked on the wind. In the alleys, I imagined Caravaggio here, knowing that men sought to kill him. I panted in fear and slugged down some more drugs from the pocket of my raincoat and felt his horror of the dark. I knew why he had painted his figures emerging from the threatening shadows into a light so luminous that it glows straight through your skin and eyes and into the seat of your capacity for love, wherever that may be. I had an answer too, to the questions Catherine posed when she and I parted in Madrid.

Stumbling down the steps toward my hotel above the gate where the Knights used to display the heads of Muslim pirates on spikes, I knew I was ready to write.

Published on July 02, 2012 01:00

•

Tags:

a-name-in-blood, art, art-history, caravaggio, crime-fiction, historical-fiction, knights-of-malta, madrid, malta, research, writing

Lost News of the World Exclusive: Caravaggio Cellphone Hacked!

The great Italian painter Caravaggio was threatened with death by the Knights of Malta and by the family of a man he had slain in a duel and was in love with one of his models, according to a scoop in The News of the World which was never published because of the demise of the London tabloid.

The great Italian painter Caravaggio was threatened with death by the Knights of Malta and by the family of a man he had slain in a duel and was in love with one of his models, according to a scoop in The News of the World which was never published because of the demise of the London tabloid.The News of the World, which was closed by owner Rupert Murdoch because of a phone-hacking scandal, appears to have gathered its information for the Caravaggio scoop by hacking into the early-Baroque painter’s voicemail.

“Caravaggio, you’re a dead man,” said one unidentified caller from a number with a Maltese country code. “We’re coming to get you.”

Another caller, whose number had a Roman area code, claimed responsibility for an attack which left Caravaggio scarred and said it was in revenge for killing Ranuccio Tomassoni in a duel in 1605. The scar was intended to mark him with shame. “But now we’ve decided to get rid of you for good,” the voice mail says.

Voice messages from a girl named Lena, the model for some of Caravaggio’s most well-known Madonnas, are described as “steamy” and “saucy” by The News of the World article.

Matt Rees, whose novel about the mysterious death of Caravaggio “A Name in Blood” was published this month in the UK, says the voice mails show that Caravaggio was ahead of his time as a painter and as a user of technology. “I’m convinced by the evidence, for example, that he used a camera obscura to obtain his characteristic light-dark effect, because he was aware of the latest scientific discoveries,” says Rees.

“I’m sure the cellphone he had in those days, however, must’ve been one of the big old ones with the separate battery pack. It’d look a lot less modern today than one of the paintings Caravaggio made four hundred years ago and which have had such an effect on the way we look at images today.”

The voice mails don’t resolve the debate over how Caravaggio died, Rees points out. “Art historians often say he died of nothing more than a fever, and the voice mails leave us wondering if it was the Knights of Malta, the Tomassoni relatives, or perhaps someone else,” Rees says. “To really understand what happened, you’d have to read ‘A Name in Blood.’”

Published on July 20, 2012 10:23

•

Tags:

art-history, caravaggio, crime-fiction, historical-fiction, historical-mystery, italy, malta