Matt Rees's Blog - Posts Tagged "research"

Long gestation and the crime novel

Crime novelists generally write a novel a year. It’s what publishers want. Some big writers—and I mean, 25 million books sold—have told me their publishers and agents complain that if they don’t produce a book a year their readers will forget them.

Crime novelists generally write a novel a year. It’s what publishers want. Some big writers—and I mean, 25 million books sold—have told me their publishers and agents complain that if they don’t produce a book a year their readers will forget them.In the case of such writers, some of those 25 million may have degenerative diseases and others may be plain stupid, but in all likelihood about 24 million of them will remember a writer whose book they read, let’s say, two years ago.

Nonetheless the expectation remains that a book a year will be forthcoming. So do all crime writers have one good idea a year? Or do ideas take longer to gestate? And if they do, where does that leave the writer who needs to get words on paper right now.

In the case of my latest novel MOZART’S LAST ARIA (out now in the UK, but not until November in the US), it was eight years between the initial idea and publication. A most un-crime-fiction-like timescale.

It began with a trip I took with my wife into the Salzkammergut, to find peace among the mountains and lakes at a time when we were living through the Palestinian intifada in Jerusalem. There we stumbled across the remote house where Mozart’s sister Nannerl had lived and a fascination with her was born.

It was nurtured through future visits to Vienna, to Prague (where Mozart’s operas are still performed in the Estates Theater, scene of his “Don Giovanni” premier), dinners with Maestro Zubin Mehta at which we discussed our mutual admiration for the great composer (though it shan’t surprise you to learn that his understanding of the music is on a somewhat, ahem, more elevated level than mine…)

Read the rest of this post on my blog The Man of Twists and Turns.

Published on May 18, 2011 23:55

•

Tags:

austria, brooklyn, crime-fiction, detective-fiction, evan-fallenberg, intifada, jerusalem, little-palestine, mozart-s-last-aria, nannerl-mozart, palestine, piano, prague, research, salzkammergut, vienna, wolfgang-amadeus-mozart, wolfgang-mozart, writers, zubin-mehta

Podcast: How to Write a Book -- Research

My latest podcast is the first of a three-part series on how to write your book. This episode is about research.

Published on August 01, 2011 03:29

•

Tags:

how-to-write, podcast, research, writers, writing

Too Many Drugs: Following Caravaggio in Malta for A NAME IN BLOOD

I left Rome to continue my research for A Name in Blood, my Caravaggio novel which is released July 1 in the UK, in Malta. Caravaggio fled to the remote island off the coast of Africa and became (briefly) a member of the Knights of Malta. It was a strange trip for me, but the isolation and pure weirdness I felt there gave me important insights for the novel.

I left Rome to continue my research for A Name in Blood, my Caravaggio novel which is released July 1 in the UK, in Malta. Caravaggio fled to the remote island off the coast of Africa and became (briefly) a member of the Knights of Malta. It was a strange trip for me, but the isolation and pure weirdness I felt there gave me important insights for the novel.I spent December in Malta in a cheap hotel in a four-hundred-year-old building that was without heating and insulation, in a room where one of the windows didn’t close. I got sick. I took some drugs, staring across the harbor at the sheets of rain plummeting down on the Castel Sant’Angelo where Caravaggio was imprisoned for a time. It got damper in my room. I took too many drugs. I hallucinated, slept at unaccustomed hours and was awake when everyone else was in bed. I saw things that weren’t there. I drank far too many espressos at the Café Merisi, which takes Caravaggio’s family name and emblazons his face on the napkins, until I was as jittery as a June bug. A June bug with an overdose.

In this condition, I stood all day before The Beheading of Saint John, Caravaggio’s largest canvas and one of his most gruesome and disturbing. He showed John the Baptist collapsing, hands bound, on the floor of a dungeon, his executioner sawing his head away and a jailor gesturing for the severed head to be placed on a platter held by a young woman. It’s the only painting where Caravaggio signed his name. And he did it in a deep red, mingling with the blood spurting from the dying saint’s neck, giving me the title of my novel: A Name in Blood.

At night I wandered the narrow, deserted, windswept streets of Valletta’s Baroque center, weaving light-headed over the flagstones under the sad Christmas lights that rocked on the wind. Loudspeakers on the street lamps played cheesy carols. Alone as I was, I sang along, laughing to myself and feeling more than a little unhinged. In the alleys, I imagined Caravaggio here, knowing that men sought to kill him. I jogged giggling up the banks of steps that connect the streets along Valletta’s high ridges, as if I were fleeing. I panted in fear and slugged down some more drugs from the pocket of my raincoat and felt his horror of the dark.

I knew why Caravaggio had painted his figures emerging from the threatening shadows into a light so luminous that it glows straight through your skin and eyes and into the seat of your capacity for love, wherever that may be.

Stumbling down the steps toward my hotel above the gate where the Knights used to display the heads of Muslim pirates on spikes, I knew I was ready to write.

Published on June 07, 2012 01:15

•

Tags:

a-name-in-blood, art, art-history, caravaggio, crime-fiction, historical-fiction, malta, naples, research, rome

Researching my Caravaggio novel: Learning to Kill

In the chapel of the Pio Monte della Misericordia, I stood before the great painting now known as Seven Works of Mercy (Caravaggio called it Our Lady of Mercy.) The noise and chaos of Naples’s narrow streets spilled through the door of the chapel, just as they had in Caravaggio’s day. I wondered at the force of personality and the drive to create that enabled him to paint this phenomenal work of devotion and love, while separated by a single door from a raucous crowd in which may have lurked the men who wanted to kill him.

In the chapel of the Pio Monte della Misericordia, I stood before the great painting now known as Seven Works of Mercy (Caravaggio called it Our Lady of Mercy.) The noise and chaos of Naples’s narrow streets spilled through the door of the chapel, just as they had in Caravaggio’s day. I wondered at the force of personality and the drive to create that enabled him to paint this phenomenal work of devotion and love, while separated by a single door from a raucous crowd in which may have lurked the men who wanted to kill him.When he first went to Naples, Caravaggio had a price on his head for a fatal duel in Rome. He returned a year later unpardoned and with the additional danger of a noble Knight of Malta eager for revenge after a brawl. Caravaggio knew how to fight and, unfortunately, was at least as eager as his peers to engage in that activity (There’s no evidence that he was the homicidal nutcase portrayed in some “documentaries” and depictions of the artist. Everyone carried a sword; most were prepared to use it; Italian men were obsessed with their honour. If Caravaggio killed a man, it represented an extreme action, but not one for which most of his pals would’ve thought any worse of him.)

So Caravaggio knew how to duel, and most of my book A Name in Blood is from his point of view, thus I too had to learn how to wield a rapier.

By coincidence (in the obsessive state of researching A Name in Blood, I sometimes thought rather that it was fated), the Academy for Historical Fencing happens to be located in the town where I was born and where my parents live: Newport, South Wales. It’s a former steel town with little apparent connection to historic chivalry, yet Nick Thomas, a Medieval and Renaissance sword enthusiast, started the Academy there.

So I found myself driving up to Caerleon, the suburb where the Romans once had a fortress, on a Friday night with my Dad, ready to do battle.

The rather dandified image of dueling is over-romanticized. “You could fight like a gentleman or like a thug,” Nick said. “But it was all about killing, in the end. So it could be said that the thug predominates.”

Nick is a delightfully obsessed martial arts fan who learned Renaissance Italian so he could translate his favorite fencing manual (Ridolfo Capo Ferro’s 1610 masterpiece, the Gran Simulacro) and has won many European rapier competitions. By day he and his brother write zombie fiction (their latest is Sherlock Holmes and the Zombie Problem). With several friends, he founded the Academy in 1996. They run classes in Bristol, England, and Newport.

The Academy class gives new recruits a choice: slam each other with the medieval broadsword or run each other through with a five-feet-long rapier. Well, figuratively, at least.

In terms of the descriptive detail I picked up, my studying with Nick was invaluable. My previous fencing knowledge was drawn from contemporary epee fighting. But the rapier is very different. For a start the sword is much heavier and no one wants a drawn out bout. Things happen faster, in a single motion, rather than by building a series of moves as in epee work. Even the way you hold the sword is different.

After strapping on my chest protector and pushing down a visor tight over my big Celtic head, I discovered that I had two favorite moves. The first is simplicity itself: as the opponent thrusts, you turn your wrist up, thus deflecting his sword past your head, and at the same time you lunge at his face. The second of my favorites is pure thuggery: parry your opponent’s sword to your right, step forward with your left foot, and drive your dagger under his armpit.

While I fenced, I learned something about Caravaggio that was at least as significant, for me as a novelist, as the technical aspects of wielding a rapier. I learned about his nerve.

For a moment, when your opponent thrusts, you see the point of his sword coming right at your eyes. It takes steadiness not to watch it come on and instead to execute the parry and riposte. To do so without protective gear would surely take what the Italians call “coglioni.” I don’t think I need to translate that. It gave me a deeper degree of understanding of Caravaggio’s character that was very important in writing A Name in Blood.

Published on June 11, 2012 03:31

•

Tags:

a-name-in-blood, caravaggio, crime-fiction, fencing, historical-fiction, martial-arts, research

Rescuing Caravaggio from a Bad Rap

He was a raging psycho, an uncontrollably lustful homosexual, and a bit of a bitch. Somehow he also managed to produce some of the most sensitive and innovative art ever painted, much of it clearly based on a sophisticated understanding of theology and optical science.

He was a raging psycho, an uncontrollably lustful homosexual, and a bit of a bitch. Somehow he also managed to produce some of the most sensitive and innovative art ever painted, much of it clearly based on a sophisticated understanding of theology and optical science.For many art historians and almost all creative artists writing about or otherwise depicting Caravaggio, the gay psycho bitch has predominated. But I wasn’t drawn to Caravaggio because he threw a plate of hot artichokes in an insolent waiter’s face (although I found it somehow appealing, nonetheless) or because he did a good line in paintings of little boy’s bottoms.

My Caravaggio novel A Name in Blood focuses on the most compelling aspects of his life and work. I was, after all, attracted to him in the first place because of his work, not because of the anti-establishment cult that was built around him in the ‘Sixties and ‘Seventies and which culminated in Derek Jarman’s tedious movie, where Caravaggio endlessly feeds gold coins into the mouth of a naked, sweaty Sean Bean. (After I made her watch the film, my wife told me: “Wow, I must really love you to sit through this shit.” She’s from New York; she can be bitchier than Cult Caravaggio. And yet I still give her my first drafts to read.)

It isn’t the first time I’ve found a historical novel of mine engaging in an unintended battle against long-held prejudices. In Mozart’s Last Aria, I wrote about the mysterious death of the great composer. In doing so, I discovered a Mozart who was a socially engaged intellectual and far more complex than the common perception of him –– which was finally cemented in the popular imagination by the giggling buffoon at the centre of Amadeus thirty years ago.

So too with Caravaggio. Take a look at the Caravaggio episode in Simon Schama’s The Power of Art series for the BBC. Caravaggio is shown practicing with his rapier and, later, stabbing a man to death with the aggressive drug-addled sneer of the front man of a punk ensemble. Schama wanders about Rome with no answer as to how Caravaggio found the time, talent, or spiritual intensity to paint the most vivid Madonnas in the history of art.

I won’t recount every example here of how Caravaggio deviates from the cartoon image of him. But here’s an example of the role his intellect must have played in his work. For one thing, I’m convinced by the research that shows he used a camera obscura. Not as a gimmick, but because he was a resident in the palace of Cardinal del Monte and dined with many of the great scientists of the day, conversing with them on a sophisticated level. He was able to put into practice much of the theory he heard at that table.

It’s true that Caravaggio did kill a man in a duel. He was often hauled up before the courts in Rome for brawling. He appears to have had sex with young men and female whores. Without wanting to be too relativistic, none of this was entirely without precedent among his peers, most of whom regarded his conduct with equanimity (unless they were jealous rivals.)

Most creative artists I’ve met (and this is true of myself) do not choose their field because they’re breezy, well-balanced types. Caravaggio was given to the tempestuous behavior of a man with a tendency to rage and, I think, depression. Probably this was a result of early traumas. We can’t know that for sure, because we don’t have his therapist’s notes…Or do we? A painter's canvasses are pretty close.

What we do know is that a man who made such fabulous and inspiring art deserves to be considered as more than just a hoodlum. We should approach him with our own finest parts attuned to the real Caravaggio who has so often been hidden under the stereotypical bad boy genius.

Published on June 12, 2012 02:09

•

Tags:

a-name-in-blood, art-history, caravaggio, crime-fiction, historical-fiction, mozart-s-last-aria, research, writing

Forging Caravaggio: Paintings for my new novel A NAME IN BLOOD

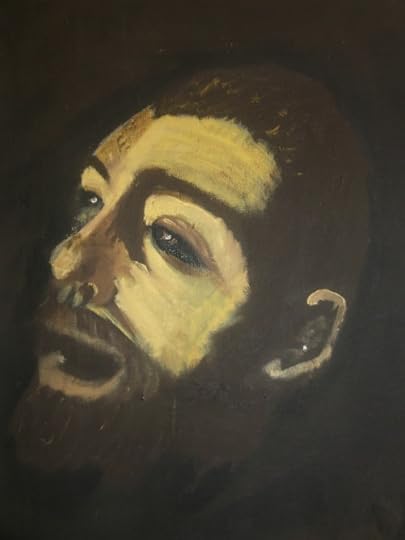

About the time Caravaggio was painting his masterpieces in Italy, Miguel de Cervantes observed that "Good painters imitate nature. Bad ones spew it up." Forging seems to me more accurate than imitation. As I researched my Caravaggio novel A NAME IN BLOOD, which is out in the UK on 5 July, I realized I had to learn how to paint with oils if I was to describe the maestro at work. Here are some of my re-forgings (because the original forgeries of nature were by Caravaggio).

Caravaggio painted his "Sick Bacchus" when he was young and penniless and living what might be described as a sordidly "downtown" lifestyle. I love the way he worked with the unhealthy skin and the rheumy eyes in his self-portrait. It's very wantonly sexual and depraved.

Caravaggio painted his "Sick Bacchus" when he was young and penniless and living what might be described as a sordidly "downtown" lifestyle. I love the way he worked with the unhealthy skin and the rheumy eyes in his self-portrait. It's very wantonly sexual and depraved.

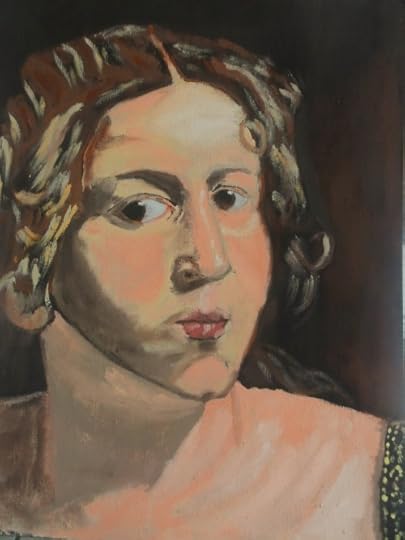

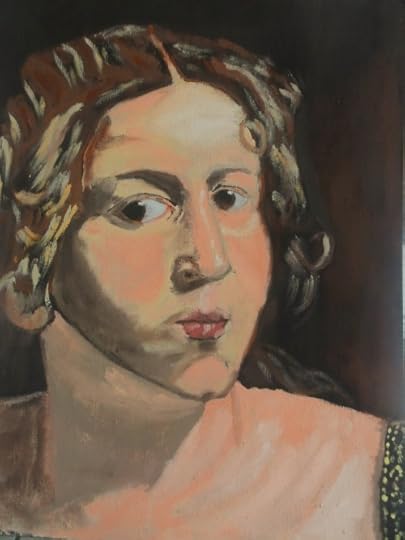

This detail from "Death of the Virgin" is important to the story of A NAME IN BLOOD. It also features Lena, Caravaggio's model and, I think, lover, as the dead woman. Whereas the big test in "Sick Bacchus" is to depict skin, here it's more to do with cloth and depth of field.

This detail from "Death of the Virgin" is important to the story of A NAME IN BLOOD. It also features Lena, Caravaggio's model and, I think, lover, as the dead woman. Whereas the big test in "Sick Bacchus" is to depict skin, here it's more to do with cloth and depth of field.

Lena was Caravaggio's model in the "Madonna with the Serpent," which as devoted readers of this blog will know is my all-time favorite painting. I painted it a number of times, working and reworking Lena's face. In this one, she came out looking rather like my maternal grandmother in her younger days...

Lena was Caravaggio's model in the "Madonna with the Serpent," which as devoted readers of this blog will know is my all-time favorite painting. I painted it a number of times, working and reworking Lena's face. In this one, she came out looking rather like my maternal grandmother in her younger days...

Caravaggio's brushwork became swifter as he went on the run from a death sentence. That's why the "Raising of Lazarus" he painted in Sicily is so fascinating to me. I even wrote a short story about it, which you can download if you like as a taster for the novel.

Caravaggio's brushwork became swifter as he went on the run from a death sentence. That's why the "Raising of Lazarus" he painted in Sicily is so fascinating to me. I even wrote a short story about it, which you can download if you like as a taster for the novel. The reason I first conceived of a Caravaggio novel was this painting. It's a detail from "St. Catherine of Alexandria," which I saw in Madrid some years ago at the Thyssen gallery. I suppose I felt seduced by the model, Fillide Melandroni. She was perhaps gulling me, because Fillide was a whore. Or maybe after 400 years, she's no longer just doing it for money...

The reason I first conceived of a Caravaggio novel was this painting. It's a detail from "St. Catherine of Alexandria," which I saw in Madrid some years ago at the Thyssen gallery. I suppose I felt seduced by the model, Fillide Melandroni. She was perhaps gulling me, because Fillide was a whore. Or maybe after 400 years, she's no longer just doing it for money...

One of Caravaggio's final paintings -- perhaps his very last -- is the "Martyrdom of St. Ursula." He had reduced his technique to the barest of light emerging from the shadows. His own face emerges over the shoulder of the saint, craning to see the arrow pierce her breast.

One of Caravaggio's final paintings -- perhaps his very last -- is the "Martyrdom of St. Ursula." He had reduced his technique to the barest of light emerging from the shadows. His own face emerges over the shoulder of the saint, craning to see the arrow pierce her breast.

Meanwhile Ursula's face is highlighted and shadowed in a way that was surely astonishing to Caravaggio's contemporaries. It's in Naples today.

Meanwhile Ursula's face is highlighted and shadowed in a way that was surely astonishing to Caravaggio's contemporaries. It's in Naples today.

Sadly for Caravaggio he never got to meet these two. It's a portrait of my wife and son. I couldn't get my wife quite as lovely as she truly is. But I think I captured the intelligent naughtiness and wit of little Cai.

Sadly for Caravaggio he never got to meet these two. It's a portrait of my wife and son. I couldn't get my wife quite as lovely as she truly is. But I think I captured the intelligent naughtiness and wit of little Cai.

Caravaggio painted his "Sick Bacchus" when he was young and penniless and living what might be described as a sordidly "downtown" lifestyle. I love the way he worked with the unhealthy skin and the rheumy eyes in his self-portrait. It's very wantonly sexual and depraved.

Caravaggio painted his "Sick Bacchus" when he was young and penniless and living what might be described as a sordidly "downtown" lifestyle. I love the way he worked with the unhealthy skin and the rheumy eyes in his self-portrait. It's very wantonly sexual and depraved. This detail from "Death of the Virgin" is important to the story of A NAME IN BLOOD. It also features Lena, Caravaggio's model and, I think, lover, as the dead woman. Whereas the big test in "Sick Bacchus" is to depict skin, here it's more to do with cloth and depth of field.

This detail from "Death of the Virgin" is important to the story of A NAME IN BLOOD. It also features Lena, Caravaggio's model and, I think, lover, as the dead woman. Whereas the big test in "Sick Bacchus" is to depict skin, here it's more to do with cloth and depth of field. Lena was Caravaggio's model in the "Madonna with the Serpent," which as devoted readers of this blog will know is my all-time favorite painting. I painted it a number of times, working and reworking Lena's face. In this one, she came out looking rather like my maternal grandmother in her younger days...

Lena was Caravaggio's model in the "Madonna with the Serpent," which as devoted readers of this blog will know is my all-time favorite painting. I painted it a number of times, working and reworking Lena's face. In this one, she came out looking rather like my maternal grandmother in her younger days... Caravaggio's brushwork became swifter as he went on the run from a death sentence. That's why the "Raising of Lazarus" he painted in Sicily is so fascinating to me. I even wrote a short story about it, which you can download if you like as a taster for the novel.

Caravaggio's brushwork became swifter as he went on the run from a death sentence. That's why the "Raising of Lazarus" he painted in Sicily is so fascinating to me. I even wrote a short story about it, which you can download if you like as a taster for the novel. The reason I first conceived of a Caravaggio novel was this painting. It's a detail from "St. Catherine of Alexandria," which I saw in Madrid some years ago at the Thyssen gallery. I suppose I felt seduced by the model, Fillide Melandroni. She was perhaps gulling me, because Fillide was a whore. Or maybe after 400 years, she's no longer just doing it for money...

The reason I first conceived of a Caravaggio novel was this painting. It's a detail from "St. Catherine of Alexandria," which I saw in Madrid some years ago at the Thyssen gallery. I suppose I felt seduced by the model, Fillide Melandroni. She was perhaps gulling me, because Fillide was a whore. Or maybe after 400 years, she's no longer just doing it for money... One of Caravaggio's final paintings -- perhaps his very last -- is the "Martyrdom of St. Ursula." He had reduced his technique to the barest of light emerging from the shadows. His own face emerges over the shoulder of the saint, craning to see the arrow pierce her breast.

One of Caravaggio's final paintings -- perhaps his very last -- is the "Martyrdom of St. Ursula." He had reduced his technique to the barest of light emerging from the shadows. His own face emerges over the shoulder of the saint, craning to see the arrow pierce her breast. Meanwhile Ursula's face is highlighted and shadowed in a way that was surely astonishing to Caravaggio's contemporaries. It's in Naples today.

Meanwhile Ursula's face is highlighted and shadowed in a way that was surely astonishing to Caravaggio's contemporaries. It's in Naples today. Sadly for Caravaggio he never got to meet these two. It's a portrait of my wife and son. I couldn't get my wife quite as lovely as she truly is. But I think I captured the intelligent naughtiness and wit of little Cai.

Sadly for Caravaggio he never got to meet these two. It's a portrait of my wife and son. I couldn't get my wife quite as lovely as she truly is. But I think I captured the intelligent naughtiness and wit of little Cai.

Published on June 26, 2012 02:01

•

Tags:

a-name-in-blood, art, art-history, caravaggio, crime-fiction, historical-fiction, research

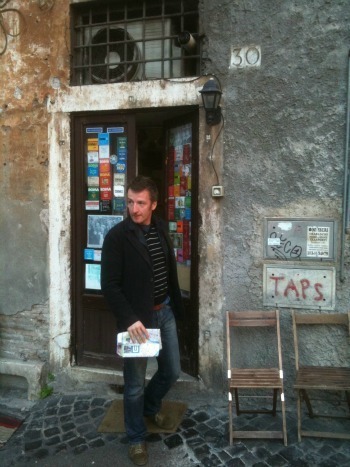

Taking My Research TOO Far: Caravaggio and Willy Wonka

As Willy Wonka says in “Charlie and the Great Glass Elevator,” the wisest men know that they need to indulge in some nonsense from time to time. Which is why I like to take my research for my novels just a bit too far.

As Willy Wonka says in “Charlie and the Great Glass Elevator,” the wisest men know that they need to indulge in some nonsense from time to time. Which is why I like to take my research for my novels just a bit too far.For A Name in Blood I did more than just read about the great Italian artist Caravaggio and look at his work. I learned to fence with a sixteenth-century rapier and to paint with oils, for example. A bit beyond the call of duty, but so far so reasonable.

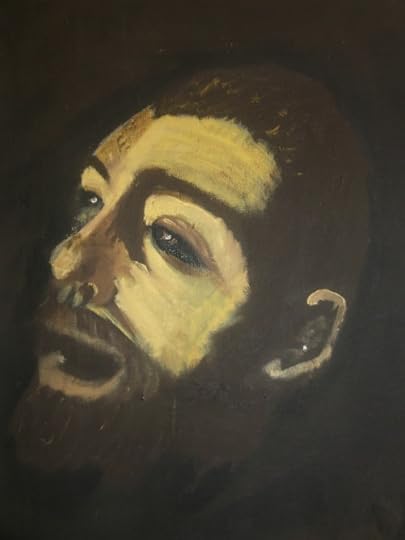

But then I decided to follow Wonka’s advice. So I grew a beard and dyed it black, because that’s how Caravaggio’s beard looked. I cut my hair in his style. I communicated with the spiritual energy of the artist and his lover in a what might be described as a very New Age fashion. I was gripped by fear and panic at night in Malta, as was he, and I got into a little, ahem, trouble in a bar in Naples. He, of course, found trouble everywhere.

The result was twofold. For one thing, it’s a stunningly good novel out in the UK on 5 July. (If I can’t blow my own trumpet, then what’s a blog post for?) But also the extra stages of my research took me so deeply into Caravaggio’s experiences that they changed my own experience of the world.

Caravaggio’s story is usually told as a tale of a brilliant painter whose tendency to violence, leading ultimately to his death at the age of 39, ruined what could otherwise have been a much more productive and happy career. After all my research, I decided the central feature of his life had been something else entirely: Caravaggio was looking for love.

How did I know this? I found it in his paintings. Look at his amazing Madonna with the Serpent and you’ll fall in love, as I did, with Lena, the model for the mother of Jesus. But more than that, behind all the dressing up and role-playing of my research was the sense that Caravaggio’s experience of life had been similar to mine. Not absolutely parallel, because fortunately my father and grandfather didn’t die of bubonic plague when I was six years old as Caravaggio’s did. (There were no recorded outbreaks in Wales in the early 1970s.) But his psychodrama was close enough to mine for me to feel a kinship with him. I’d summarize it thus: like him, I have a deep creative urge that’s rooted in what felt to me, at least, like childhood upheaval; I’ve often been compelled to work for people I despised; our romantic histories are complicated; anger has been… a problem; neither of us lived long in one place; we both found love.

That’s why I didn’t leave my interest in him on the gallery wall. I had to make of him a book, because I believed his story would help me make sense of my own emotions.

Without giving away the story of A Name in Blood, I’ll tell you that Caravaggio’s early paintings show a yearning for love in a man with little control over his life. His middle paintings reflect a sense of the love that he found. The late paintings show a man on the run (under sentence of death) who only then appreciates the depth of his love, both physical and spiritual.

Now that A Name in Blood is about to be published, I don’t have to keep dying my beard. But Caravaggio’s still with me. I hope he’ll soon be with you, too.

Published on June 28, 2012 02:05

•

Tags:

a-name-in-blood, art, art-history, caravaggio, crime-fiction, historical-fiction, renaissance, research

Podcast: Touching Caravaggio, Researching 'A Name in Blood'

My latest podcast describes the challenges of researching and writing about the great Italian artist Caravaggio for my novel A NAME IN BLOOD. I deliberately took my research too far, not only learning to fence with a rapier and to paint with oils, but dying my beard and cutting my hair in Caravaggio’s style and using New Age spiritual techniques to connect with the energy of Caravaggio. I did all this because I wanted to be sure I could accurately portray the real Caravaggio, not the “gay psycho bitch” as whom he’s usually portrayed. Here’s how I found the real Caravaggio.

Published on July 01, 2012 01:25

•

Tags:

a-name-in-blood, art-history, caravaggio, crime-fiction, historical-fiction, italy, podcast, research

Behind the Book: Writing My Caravaggio Novel A NAME IN BLOOD

On the upper floor of the Museo Thyssen-Bornemisza in central Madrid, I wandered into a broad room where the masterpieces were arrayed like chocolates in a box. Just as with an assortment of sweets, I knew immediately and innately which one attracted me. I stepped into the arms of Caravaggio’s Saint Catherine of Alexandria. She still hasn’t let me go.

On the upper floor of the Museo Thyssen-Bornemisza in central Madrid, I wandered into a broad room where the masterpieces were arrayed like chocolates in a box. Just as with an assortment of sweets, I knew immediately and innately which one attracted me. I stepped into the arms of Caravaggio’s Saint Catherine of Alexandria. She still hasn’t let me go.I was in Madrid on a book tour for the Spanish translation of the first of my Palestinian crime novels. The Thyssen is just across the wide, busy Paseo del Prado from the immense museum of that name. It’s a building with two wings: a traditional classical palace in burnt sienna and pink stone; alongside a block of bright white louvered walls and angled blue-glass rooflights, like an old auto factory transported to a sci-fi future. I had no idea what awaited me inside. It was a novel.

The Caravaggio works I had previously seen in London and New York had impressed me. I was aware of the conventional summary of the stylistic revolution he wrought: to fill his canvasses with darkness and, with a strategically placed lantern, to bring the central action shining out of the shadows. That technique has been a major influence on filmmakers like Scorsese and almost every professional photographer, which is why Caravaggio’s four-hundred-year-old paintings look so modern. I knew something about his life too, though largely through the weird distortions and art-house tedium of Derek Jarman, having seen the British director’s Caravaggio film in college. As a writer, however, I’ve found a confluence of impressionability and idea lies behind every novel, so that only at one given time can you write a particular novel. A few years previously, I might’ve seen Saint Catherine, considered her for a moment, then moved on, as I had done when I saw Caravaggio’s The Supper at Emmaus in London’s National Gallery. But, for some reason, when I entered her room at the Thyssen and she spoke to me, I was listening.

I stayed in that room a long time. I couldn’t say quite how long. But it was at least an hour. The other paintings held my attention a matter of moments. I can’t remember them. (I’ve had similar experiences when I’ve traveled to see Caravaggio’s art around the world since then. No artist has such a capacity to make everything else in a gallery ignorable as Caravaggio has). In the Thyssen, I recall that the walls were of a beige rough fabric, a little like delicate sackcloth. The ceiling was white. Details as scant as you might retain from love-making. You might forget your mood or the immediate surroundings, but you’d have a clear picture of the way she looked at you or the feel of her hand on the back of your neck. Of Catherine, I remember everything. Even things that weren’t on the canvas.

The eyes of Caravaggio’s saint were possessive, grasping and sensual, clandestine and forbidden. For much of the time I was with her, we were alone. It felt as intimate as the languor after an act of love. There’s a question in that post-coital moment and Catherine asked it of me: Is this the last time? Will I see you again? Do you want to know more about me and where I come from?

Eventually I tried to leave the empty room. In her face I saw a plea. As if she wanted me to know that by leaving I would abandon her to her fate, represented by the spiked wheel on which she leaned (where the saint was tortured, before she was dispatched with the sword whose shaft she fondles.) What’s so compelling (and in his day was controversial) about Caravaggio is that he didn’t expect the saint’s suffering to be enough to keep you on her side. He gave her the sexual magnetism of Fillide Melandroni, the whore he used as his model.

The hold Caravaggio subsequently took on me amounted to what many people would call an obsession. I prefer not to use that term, because it implies a degree of madness and the inability to see when you’re mistaken about something. A writer needs to know when he’s gone wrong. Still, I traveled all over Europe and America to see Caravaggio’s works. I learned to paint with oils, to fight with a rapier. I grew a beard like the one Caravaggio sported just before his death at age 39. I did a few others things that paralleled the artist’s life and which were too intimate, shameful, or mystical to be recounted here. So, go ahead, call it an obsession.

After Madrid, my long road of research began with Peter Robb’s fabulous biography “M: The Man Who Became Caravaggio.” An Australian who lived a long time in southern Italy, Robb’s account of Caravaggio’s life is detailed in a non-academic way and deeply felt. He examines the mystery surrounding Caravaggio’s disappearance without prejudice, which earned Robb quite a deal of criticism from Caravaggio “scholars” when he published his book in 1998. The “accepted” version of Caravaggio’s demise is a tall tale of mistaken identity, a mad scamper along a malarial coastline, fever, death in a Tuscan convent and an unmarked grave. Academics tend to assume that considering anything other than this hashed-over version of Caravaggio’s death represents a foray into sensationalism, rather than simple curiosity about how this most dynamic of Italian artists simply vanished. (I had encountered a similar preference for the boring and quotidian in professors writing about Mozart’s death, while I researched the composer’s mysterious end for my novel Mozart’s Last Aria. Somehow academics seem committed to taking history’s dramatic events and making them appear as banal as another day in the faculty canteen, and they get inordinately angry with someone like me who decides to eat lunch off campus.)

It’s a considerable undertaking to write a novel about an artist whose works are dispersed around the world, whose pictorial skills you don’t share, and whose life was lived in such a distant time. But I didn’t think for a moment that I shouldn’t write the book. Well, okay, so it really was an obsession…

I traveled throughout Italy to see the places that touched Caravaggio’s life. In particular I spent a lot of time in the historic center of Rome, the neighborhoods around the Piazza Navona which are now the tourist heart of the ancient city. In Caravaggio’s day, this was the “Evil Garden,” where the Pope decreed the whores should live. Naturally, where there were whores, there were artists and trouble. In Rome, once more I found a communion with a Caravaggio painting. This time it was perhaps deeper even than the one I shared with Catherine. At the Galleria Borghese, I sneaked around the guards who usher on lingerers so newcomers may pile through the galleries built by Caravaggio’s patron Cardinal Scipione Borghese. I needed more time with the Madonna with the Serpent. This Madonna is based on a girl named Lena, who I made a major character in my novel. I wouldn’t even quibble to say I obsessed about her. I fell in love, and it was clear to me that Caravaggio couldn’t have painted her the way he did unless he had shared that emotion. Here is where some of the mystical aspects of my research come in. I won’t go into detail about them. I’ll only say that I feel as though I’ve met this girl Lena. Certainly, when I learned to paint with oils so as to be able to describe how Caravaggio worked, I painted Lena over and over.

From Rome, I went on to Naples, where Caravaggio took refuge. In the chapel of the Pio Monte della Misericordia, I stood before the great painting now known as Seven Works of Mercy, which is topped by another Lena Madonna (Caravaggio called it Our Lady of Mercy.) The noise and chaos of Naples’s narrow streets spilled through the door of the chapel, just as they had in Caravaggio’s day. I wondered at the force of personality and the drive to create that enabled him to paint this phenomenal work of devotion and love, while separated by a single door from a raucous crowd in which may have lurked the men who wanted to kill him (By the time he went to Naples, Caravaggio had a price on his head for a fatal duel.)

Dueling was another element of my research. I had to know how it felt to wield both a brush and a rapier. By coincidence (in my obsessive state, I sometimes thought it was fated), the Academy for Historical Fencing happens to be located in the town where I was born and where my parents live: Newport, South Wales, a former steel town with little apparent connection to historic chivalry. Nick Thomas, a Medieval and Renaissance sword enthusiast, started the Academy there and so I found myself driving up to Caerleon, the Newport suburb where the Romans once had a fortress, on a Friday night with my Dad, ready to do battle. Within moments of strapping on my chest protector and pushing down a visor tight over my big Celtic head, I found myself amazed at the balls it must have taken to duel with these five-feet-long swords without protective gear. The tip of my opponent’s blade mesmerized me. To fight, I’d have to ignore this point that—in Caravaggio’s circumstances—would’ve killed me in one thrust. It took some doing, I can tell you.

I journeyed on to Malta, where Caravaggio fled and became (briefly) a member of the Knights of Malta. I spent December there in a cheap hotel in a four-hundred-year-old building that was without heating and insulation, in a room where one of the windows didn’t close. I got sick. I took some drugs, staring across the harbor at the sheets of rain plummeting down on the Castel Sant’Angelo, where Caravaggio was imprisoned for a time. It got damper in my room. I took too many drugs. I hallucinated, slept at unaccustomed hours and was awake when everyone else was in bed. I saw things that weren’t there. In this condition, I stood all day before The Beheading of Saint John, Caravaggio’s largest canvas and one of his most gruesome and disturbing. It’s the painting where he signed his name—the only time he ever signed a work. And he did it in a deep red, mingling with the blood spurting from the dying saint’s neck, giving me the title of my novel. At night I wandered the narrow, deserted, windswept streets of Valletta’s Baroque center, weaving light-headed over the flagstones under the sad Christmas lights that rocked on the wind. In the alleys, I imagined Caravaggio here, knowing that men sought to kill him. I panted in fear and slugged down some more drugs from the pocket of my raincoat and felt his horror of the dark. I knew why he had painted his figures emerging from the threatening shadows into a light so luminous that it glows straight through your skin and eyes and into the seat of your capacity for love, wherever that may be. I had an answer too, to the questions Catherine posed when she and I parted in Madrid.

Stumbling down the steps toward my hotel above the gate where the Knights used to display the heads of Muslim pirates on spikes, I knew I was ready to write.

Published on July 02, 2012 01:00

•

Tags:

a-name-in-blood, art, art-history, caravaggio, crime-fiction, historical-fiction, knights-of-malta, madrid, malta, research, writing