Matt Rees's Blog - Posts Tagged "art"

Stealing the novel, really

Every couple of days a little alert pops up in my email account letting me know that I can read my books for nothing in Norwegian. My Norwegian’s not so great and I can read my books for nothing any time. But that’s not the point.

Every couple of days a little alert pops up in my email account letting me know that I can read my books for nothing in Norwegian. My Norwegian’s not so great and I can read my books for nothing any time. But that’s not the point.Scandinavia is a major center of so-called Cyberpunks who have willfully misinterpreted an old hacker adage that “information wants to be free” to mean “go ahead and steal things from which someone else expects to earn his livelihood.” Such Cyber types have, among other things, loaded electronic versions of my novels in Norwegian onto the internet so that anyone can take them without paying.

It’s a little odd. Anyone who’s been to Scandinavia will see that the locals are perfectly willing to pay through the nose for things which ought to be cheap. Even if they actually bought my novel, it’d still be cheaper than the train ride from Oslo Airport to downtown Oslo or a sandwich and soda by the fjord. And everyone’s so nice. Maybe that’s the problem–they’re trying to be nice to information. As long as they believe that the information wants to be free, then they’re only helping the information out by taking it for nothing…

It’s all the thin end of a disturbing wedge for creative artists such as yours truly who support their families entirely from their endeavors as authors, artists, musicians – and who for the most part would be somewhat better remunerated were they to choose to drive a bus for a living.

Information wants to be free but, as the original coiner of that phrase noted, information also wants to be expensive. If information is the catalogue of the Library of Congress, make it free. Sure, let’s have free access to recipes from Renaissance Florence and the geology of the Grand Canyon.

But not art. Art doesn’t want to be free. Art wants to be labored over by a person whose mind isn’t distracted by other things. Art wants to be made as good as it can be. Art wants creative dedication, it doesn’t want to be zapped out by people in a hurry who have to do a day-job, too.

Art, needless to say, is not just information.

Of course we can all justify a little theft. When I was a teen, I used to steal books. But only from big chain bookstores and only from authors who were long dead. The one time I broke those self-imposed rules, I nearly got tossed out of university for lifting a copy of a book written by my tutor’s wife from the college library before the librarian had even got around to cataloguing it. Anyhow, I gave that one back, because my education was free, so I was content for that particular bit of information not to be.

Others use Ebay to salve their conscience. For example, some penny-pinching Scot is offering for sale on Ebay Advance Uncorrected Proofs of my novels. These are sent out free to reviewers and booksellers before the books appear on the shelves. They’re clearly marked “Not for Resale” in big letters on the cover.

It could be that this person in Scotland would’ve behaved differently had the words “Nae fer resale” appeared in dialect on the cover. But I suspect that this person thinks that selling something dishonestly on the internet isn’t really dishonest. If that person were to walk into a second-hand bookstore and face a bookseller with his clearly marked “Not for Resale,” he’d feel a little ashamed at asking money for it. In selling just as in the writing of offensive anonymous comments, the internet is a shield for our worst behavior.

Well, as they say in Scotland, dinna fash yersel. I’ll manage, even if there are a few such novel proofs flying about. But think of poor Stephenie Meyer. Her blog mentioned not so long ago that someone had posted an early draft of her next novel on the internet and that hundreds of thousands of people had downloaded it.

(An aside: why on earth would anyone read an early draft of a novel unless they had to do so? Novels aren’t flash fiction. They take a long time and lots of work to make them right and until they’re right the reading of them can be pretty dire.)

Hey, you say, she’s not short of cash. Well, what’re you, a communist? Robin Hood?

Okay, Meyer’s no doubt quite rich as a result of her strange subgenre. But she’s not Goldman Sachs. She isn’t marketing worthless things to people, intending for them to lose millions of dollars and enrich her in return. She’s being paid for the enriching experience of reading for those who buy her books.

When I mentioned to some friends that this sort of thing went on with books, they were surprised. Each of them noted that they had taken music and movies from the internet in just the same way. Each also said that they figured Roman Polanski was rich enough to let them have a free look at “The Ghost Writer.” That Bono would still be able to afford fancy sunglasses if they ripped off his latest album.

But remember, Cyberpunks are anarchists. Do you really want them to define the way you live? When was the last time you read a good book by an anarchist?

As the recently deceased Malcolm McLaren always noted, even The Sex Pistols with their claim to be anarchists were only in it for the money.

Published on April 29, 2010 00:34

•

Tags:

art, bono, crime-fiction, cyberpunks, ebay, goldman-sachs, grand-canyon, internet, library-of-congress, malcolm-mclaren, norway, oslo, roman-polanski, scandinavia, scotland, stephenie-meyer, the-ghost-writer, the-sex-pistols, u2

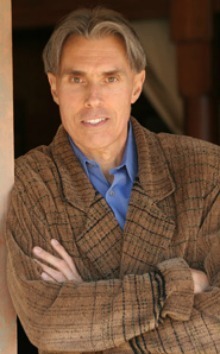

What do YOU think of me?

A friend of mine was lunching with a Scandinavian author a while back. At one point, the writer joked: “But that’s enough of me talking about myself. What do YOU think of me?”

A friend of mine was lunching with a Scandinavian author a while back. At one point, the writer joked: “But that’s enough of me talking about myself. What do YOU think of me?”Unlike that writer, I don’t care what you think of me. Don’t be offended – I don’t care what I think about other people, either. The more I write, the more I realize that I’m interested in myself alone.

That, I believe, is the necessary focus of all art – even if its final aim is to turn that inward look out toward the reader, the viewer, the listener. Art is flawed unless it focuses on the artist’s relationship with the world around him – through the narrator’s voice, in the case of a novelist.

I’ve been poring over this for a while, but it came to the fore last week after I spoke to an American group visiting Jerusalem. Mimi Schwartz, a writer of creative nonfiction, approached me after the event. She was kind enough to say that my long tenure here in Jerusalem – next month it’ll be 14 years – gave me a valuable perspective on the place. She suggested I write a memoir, in between my crime novels, because it would allow me “to bear witness.”

When I think of writing nonfiction about my experiences here, I tend to view the likely outcome as being David Sedaris-style essays telling amusing tales or a one-man-show in a similar vein. I don’t think that’s quite what Mimi had in mind. (She seemed like a lady of broad curiosity. I don’t think she’d be upset.)

I don’t want to “bear witness.” What I’ve witnessed in Jerusalem, Nablus, Tel Aviv, Gaza – none of it seems to have any value, frankly, unless I can tell you how I feel about it. Otherwise it’s just a litany of body parts and angry people and failed politics and disappointing lives.

I don’t mean to suggest that art has to be uplifting. But it has to open reality out, spread it wider than the small scope of journalism. That’s why much photography often seems to me to be the sneaky little charlatan of the arts world, because it’s so frequently done for the eye-catching cool beloved of ad-men or with an empty-eyed blandness.

By the same token, art may descend too far beyond the personal. The solipsistic crap that passes for contemporary art is the flipside of the banality of the mediocre photographer.

So all (bearable) art is, in a sense, bearing witness. Because it must be based firmly in something real. If it isn’t based in something real, then it doesn’t come as a reaction on the part of the artist to a real experience – and there’ll be something about it that tips the reader or viewer to the fact that the artist is lieing about or obscuring himself.

My series of four crime novels about Omar Yussef, a Palestinian detective, obviously have an element based in reality, because Omar is a way for me to unfold the scenes and emotions through which I’ve lived these past 14 years. But my next novel, which is to be about the death of Mozart, will just as surely be based in my experience of how people react to a loss and the dirty reality that’s likely to lie behind a sudden death.

To do my bit of bearing witness, I plan to stick to fiction. It’s closer to the real truth.

Published on May 06, 2010 01:23

•

Tags:

art, contemporary-art, creative-nonfiction, crime-fiction, david-sedaris, fiction, gaza, israel, jerusalem, journalism, middle-east, mimi-schwartz, mozart, nablus, nonfiction, omar-yussef, palestine, palestinian-detective, photography, tel-aviv

More Passion!

British Prime Minister David Cameron recently invited Tracey Emin, a purveyor of work which is shit even by the standards of contemporary art, to produce something – they probably call it “an installation” – for Number 10, Downing Street.

British Prime Minister David Cameron recently invited Tracey Emin, a purveyor of work which is shit even by the standards of contemporary art, to produce something – they probably call it “an installation” – for Number 10, Downing Street.Emin, who won the Turner Prize for exhibiting her own used-condom-strewn bed some years ago, is a fan of Cameron. Yes, can you believe it, an artist supporting the fellow who abolished the Arts Council. She has been quoted as saying that his government is “the best government at the moment we’ve ever had.” Which shows that she’s as much of a political analyst as she is an artist.

Now, I don’t know why they’d need any new “art” in Number 10. Surely the place is chock full of Nineteenth Century paintings of horses. And at a time when the government is cutting back every ministry’s budget by at least 25 percent?

So what did Emin do for Cameron? A neon sign emblazoned with the words: “More Passion.”

Yes, indeed. The artist whose works evoke only negative passions (in me, for

one) urges the starchy Old Etonian and his coterie of distant, heartless

nobs to show more passion. No doubt she intends for them to throw caution to the winds when wielding the red pencil over university budgets and healthcare costs for old people. Show some passion; cut another million quid.

Here’s the true irony of Emin’s neon nonsense: politicians always claim to

be operating on the basis of passion and so do contemporary artists. Yet

both are clearly more interested in cash and have a corrupt ability to manipulate others into swallowing their feigned feelings.

I’ve always thought of art as going directly to your heart or your stomach.

Which is why “contemporary art” leaves me so cold. Art which requires

explanation before impact isn’t art. It may be “design,” but most likely

it’s faddish and aimed to shock. Take passionate Tracey Emin’s famous tent

installation onto which she attached the names of all the people she’d slept

with. Makes you think, eh? Well, no, actually it doesn’t. Unless it makes

you think that it’s a waste of time and that you’re lucky your name isn’t

there.

Read the rest of this post on my blog The Man of Twists and Turns.

Published on August 25, 2011 03:51

•

Tags:

art, britain, contemporary-art, crime-fiction, david-cameron, literary-fiction, politics, tracey-emin

On Caravaggio’s Trail: Travelling to Research A NAME IN BLOOD

As I researched A Name in Blood, my novel of Caravaggio, I went all over Europe and North America, tracking Caravaggio's works and the places that touched his life. The period locations I visited gave me a flavour for Caravaggio’s life. In some cases, they gave me ideas for plot twists in the book.

Everywhere I found people fascinated with this most compelling of artists. On one of my sojourns in Rome, there was an exhibition devoted to Caravaggio's use of mirrors to project images (over which he painted, giving the vivid realistic feel people usually notice when they first see his work). He used his own head, probably in a convex mirror, to paint his "Medusa," which ended up in Florence at the Galleria Uffizi. The Rome exhibit made a nice mock up. Life size, as you see, though perhaps not as scary as a traveling author making a funny face.

Caravaggio lived most of his time in Rome in the palaces of wealthy patrons. For a brief period, he rented this house (right) in a tiny street in Rome's historic center. Then he fell behind on the rent, lost the place, got drunk and went around to break his landlady's windows. I stood in the tiny alley imagining what it must have been like to be Madama Bruni, with a raging nutcase hurling rocks at her shutters from a yard away and bellowing that he was going to carve her up. Unfortunately I had to cut that incident out of A Name in Blood because, as with some other juicy moments in Caravaggio’s life, they were deeply revealing, but they didn’t drive my narrative forward.

Caravaggio’s model (and, I think, lover) Lena lived here (left). In the Via dei Greci. In the heart of what used to be the Ortaccio, or Evil Garden, where only whores and the very poor lived. And artists, of course. Both places are now very expensive spots in the middle of Rome’s tourist area. But they're still redolent of C's time. At night, they're dark and empty. Though not spooky. I never get spooked in Rome. I’m too damned happy there.

Rome was an important stop on my researches into period locations (as opposed to my more farflung journeys to the many galleries housing Caravaggio’s work), but Malta was in many ways the most compelling, because Caravaggio’s influence is still so considerable. Caravaggio is an important figure for its capital, Valletta, where he became a Knight of Malta and painted one of his masterpieces, The Beheading of Saint John for the city’s cathedral. Father John Critien (right) is the only Knight of Malta who currently lives in Castle Sant'Angelo on Valletta's harbor. C was imprisoned here, and made a dramatic escape. Father John and I spent a delightful afternoon examining all the spots where Caravaggio might've been held. Many think it was in a hole in the rock called the guva.

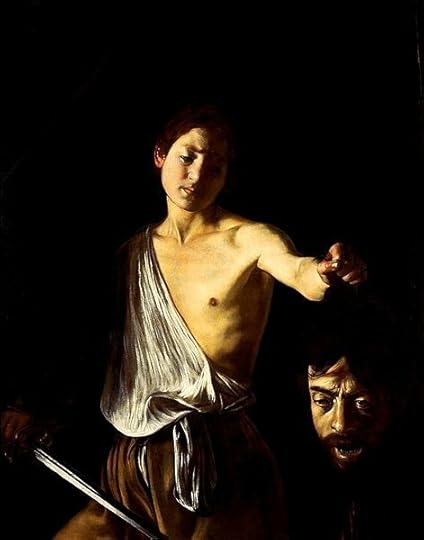

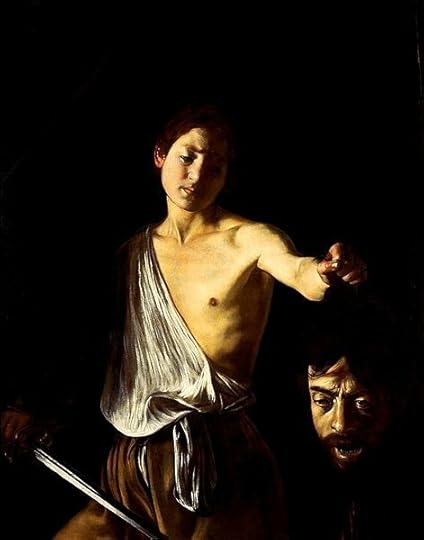

On to Naples I went. At left is the site of the Ceriglio Tavern, where Caravaggio was attacked on his way out. He got a scar, probably just to teach him a lesson rather than an attempt to kill him, and an injury to his eye, which can be seen in his last work, David with the Head of Goliath. I noticed that for much of the afternoon anyone leaving the Ceriglio and headed toward Caravaggio's digs at what’s now called the Palazzo Cellamare would be blinded by the sunlight. A good time for an attack.

My friend Ugo Somma, far right, showed me around Naples. Here he is examining the chapel of the Knights with a fellow named Rosario who works for the Knights of Malta in Naples. At first Rosario wouldn't let us look around the Knights' church. But when I told him he looked like Caravaggio, he relented and even introduced me to his sister...

At the Knights' Priory in Naples, these fellows were hanging around in the courtyard looking like mafia capos waiting to rub someone out. A non-Neapolitan had been named that morning as the new Prior. They were, as the Italians say, "arrabiati." Mad as hell. Their sullen expressions and taciturn demeanor gave me an idea for a plot twist in A Name in Blood….

My son became an aficionado of Caravaggio as the research went on. He visited many of the galleries and churches in Rome where Caravaggio’s paintings hang. When I was painting my own versions of Caravaggio’s Madonnas, I told him the woman was named Mary. He decided we had to call his new sister by that name, which we did (in the Welsh fashion, it’s spelled Mari.) His name being Cai, we dubbed him Cairavaggio.

One of my earliest memories is of a schoolteacher who had been in Naples with the British army in World War II. He wasn’t talkative, but one day he told me about a hunchback who had beckoned him to a garden and shown him the most beautiful sight he had ever seen: the perfect view over the Bay of Naples. Somehow that simple recollection of beauty by an old man, unfolded in an uncomplicated way to a small boy, brings tears to my eyes. I found the same beauty in Naples—alongside considerable depravity, too. They say, "See Naples and die." Unfortunately for Caravaggio, that's how it worked out, quite literally. Naples is magical, lively, putrid and beautiful. From the Spanish Palace looking at San Francesco, here's one moment when I thought: Matt, you lucky fellow, isn't "research" great?

Published on June 06, 2012 04:10

•

Tags:

a-name-in-blood, art, art-history, caravaggio, crime-fiction, historical-fiction, malta, naples, rome

Too Many Drugs: Following Caravaggio in Malta for A NAME IN BLOOD

I left Rome to continue my research for A Name in Blood, my Caravaggio novel which is released July 1 in the UK, in Malta. Caravaggio fled to the remote island off the coast of Africa and became (briefly) a member of the Knights of Malta. It was a strange trip for me, but the isolation and pure weirdness I felt there gave me important insights for the novel.

I left Rome to continue my research for A Name in Blood, my Caravaggio novel which is released July 1 in the UK, in Malta. Caravaggio fled to the remote island off the coast of Africa and became (briefly) a member of the Knights of Malta. It was a strange trip for me, but the isolation and pure weirdness I felt there gave me important insights for the novel.I spent December in Malta in a cheap hotel in a four-hundred-year-old building that was without heating and insulation, in a room where one of the windows didn’t close. I got sick. I took some drugs, staring across the harbor at the sheets of rain plummeting down on the Castel Sant’Angelo where Caravaggio was imprisoned for a time. It got damper in my room. I took too many drugs. I hallucinated, slept at unaccustomed hours and was awake when everyone else was in bed. I saw things that weren’t there. I drank far too many espressos at the Café Merisi, which takes Caravaggio’s family name and emblazons his face on the napkins, until I was as jittery as a June bug. A June bug with an overdose.

In this condition, I stood all day before The Beheading of Saint John, Caravaggio’s largest canvas and one of his most gruesome and disturbing. He showed John the Baptist collapsing, hands bound, on the floor of a dungeon, his executioner sawing his head away and a jailor gesturing for the severed head to be placed on a platter held by a young woman. It’s the only painting where Caravaggio signed his name. And he did it in a deep red, mingling with the blood spurting from the dying saint’s neck, giving me the title of my novel: A Name in Blood.

At night I wandered the narrow, deserted, windswept streets of Valletta’s Baroque center, weaving light-headed over the flagstones under the sad Christmas lights that rocked on the wind. Loudspeakers on the street lamps played cheesy carols. Alone as I was, I sang along, laughing to myself and feeling more than a little unhinged. In the alleys, I imagined Caravaggio here, knowing that men sought to kill him. I jogged giggling up the banks of steps that connect the streets along Valletta’s high ridges, as if I were fleeing. I panted in fear and slugged down some more drugs from the pocket of my raincoat and felt his horror of the dark.

I knew why Caravaggio had painted his figures emerging from the threatening shadows into a light so luminous that it glows straight through your skin and eyes and into the seat of your capacity for love, wherever that may be.

Stumbling down the steps toward my hotel above the gate where the Knights used to display the heads of Muslim pirates on spikes, I knew I was ready to write.

Published on June 07, 2012 01:15

•

Tags:

a-name-in-blood, art, art-history, caravaggio, crime-fiction, historical-fiction, malta, naples, research, rome

Meeting Caravaggio at the Cafe: Mystical Research for my Novel

In a Jerusalem café, I was drinking an espresso with Stephen Victor, an Oregon-based practitioner of a process called “family constellations.” I mentioned to him that I thought the process might be useful in my research for A Name in Blood, my historical novel about Caravaggio. Stephen agreed. Though the most common use of constellations is to resolve a family trauma that may even have occurred generations ago and been passed down to those living today, Stephen suggested that if I wanted to connect with Caravaggio about his life I should “just ask him––he’s out there.”

In a Jerusalem café, I was drinking an espresso with Stephen Victor, an Oregon-based practitioner of a process called “family constellations.” I mentioned to him that I thought the process might be useful in my research for A Name in Blood, my historical novel about Caravaggio. Stephen agreed. Though the most common use of constellations is to resolve a family trauma that may even have occurred generations ago and been passed down to those living today, Stephen suggested that if I wanted to connect with Caravaggio about his life I should “just ask him––he’s out there.”It was only a flash, but in that instant Caravaggio was sitting at Stephen’s right, opposite me. He wasn’t precisely “in a chair” next to Stephen. He was higher up, as if inset in a thought bubble. He was in the Jerusalem café, but he also appeared at the same time to be in a tavern in Rome four hundred years ago. He looked sad and yet comfortable in our presence.

Stephen knew Caravaggio was there too. He shivered violently and then shook it off with a twitch of his neck.

Subsequently I used constellations –– or more precisely I “just asked” Caravaggio and others in his life –– to feel my way deeper into the characterizations of A Name in Blood. Most particularly I found a response from Lena, the young woman who I believe was Caravaggio’s lover and who plays a central role in A Name in Blood.

As Stephen often says, this process is intellectually indefensible. So I don’t try to defend it. It happens to be what I’ve experienced, and when I’ve spoken to other creative artists, to actors and musicians, the most open ones often tell me they’ve had similar experiences or used similar techniques. Several German actors spent a night swapping constellations tales with me a year or so ago. My reading of some elliptical statements by Booker-award-winner Hilary Mantel suggests to me she may employ some similar process to achieve her astonishingly vivid characterizations.

The essence of the technique is to centre oneself in a meditative fashion. To focus one’s energy in one’s stomach, rather than in the head. The head is where we judge ourselves negatively––where we tell ourselves that this is all intellectually indefensible and we shouldn’t bother with it. In family constellations, when I’ve been open enough, I’ve felt the energy of someone else’s grandfather or someone’s fear or disease and allowed it to emerge as part of a healing process for that person. It’s the most remarkably cleansing feeling I’ve ever experienced.

Naturally I’ve heard from some people that this is nonsense. After I mentioned constellations while on a panel at a book fair, one of the other panelists, a very well-known British crime writer, joked: “I’m not channeling anyone. I’m doing all the typing.” A lady in the audience stood up to tell him that she thought his characterizations were very good and, therefore, she suspected he was employing something like the constellations technique without even knowing it.

Of course I’m doing the typing. I’m not channeling anyone or anything. Caravaggio didn’t write A Name in Blood, I did. If I was channeling him, I’d be painting, not writing, believe me.

But if you, like my British crime writer pal, think your head holds all the answers to everything, why does it choose to make life so miserable much of the time. Why does it fear an answer that might originate in some other part of the body?

In the West, there’s a tyranny of the brain, of the intellectually defensible. It’s like any of the other tyrannies we’ve embraced –– patriarchy, capitalism, monotheism. It demonizes any other way of thinking and often does so through mockery. If those systems don’t always work, they can be nipped and tucked, but don’t you even think of looking elsewhere for a better system. That’s the message at the heart of our culture of intellectual defensibility.

Personally I want my novel to be as good as it can be (and for me to be as happy as I can be). I don’t care what apparently silly things I have to do, what processes I must engage in, to get it that way. I know that A Name in Blood has been touched by Caravaggio, even if some might think that sounds daft.

Besides, the Caravaggio I met wasn’t at all the way you’d think from the writings of art historians. Their Caravaggio, as I’ve written elsewhere on this blog, was some kind of gay psycho bitch. But mine was different. I liked him. I hope you will too.

Published on June 14, 2012 02:57

•

Tags:

a-name-in-blood, art, art-history, baroque, caravaggio, crime-fiction, historical-crime, historical-fiction, renaissance, writing

My Caravaggio songs: The music of A NAME IN BLOOD

Art ought to inspire us at least to try to work in all the media to which we have access. I'm a writer. But I love to make music, which is partially why I wrote about the mystery of the great composer's death in Mozart's Last Aria. Writing that novel took me deeper inside some great music and helped me develop my own playing. The same is true of painting. For my new novel, A NAME IN BLOOD, I learned to work with oils. But I also wanted to incorporate these different interests. The result was my Poisonville project: original music about crime fiction. Two of the songs I've recorded are about A Name in Blood.

Art ought to inspire us at least to try to work in all the media to which we have access. I'm a writer. But I love to make music, which is partially why I wrote about the mystery of the great composer's death in Mozart's Last Aria. Writing that novel took me deeper inside some great music and helped me develop my own playing. The same is true of painting. For my new novel, A NAME IN BLOOD, I learned to work with oils. But I also wanted to incorporate these different interests. The result was my Poisonville project: original music about crime fiction. Two of the songs I've recorded are about A Name in Blood.“A Name in Blood,” is released in the UK July 5. It's about the mystery of Caravaggio's disappearance. In July 1610, he was on the run with a price on his head and he simply disappeared. Art historians have accepted a fairly tall tale about how this happened. My novel is my answer.

Caravaggio was a rebellious, sensitive man who changed art. In writing music for the book, I thought of a kind of parallel. If Lou Reed had been around 400 years ago, he’d have been a pal of Caravaggio, so I gave this song his sound.

A favorite painting “Sick Bacchus” is a self-portrait painted when Caravaggio was young and looking a bit peeky. This song captures the rawness of his life and the revolutionary style of his art. I gave it an industrial rock sound, because he was living a "downtown" sort of life at that time.

Listen to more of my Poisonville songs. Buy the songs on CDBaby or amazon.

Published on June 15, 2012 00:52

•

Tags:

a-name-in-blood, art, art-history, caravaggio, crime-fiction, historical-fiction, industrial-music, lou-reed, music

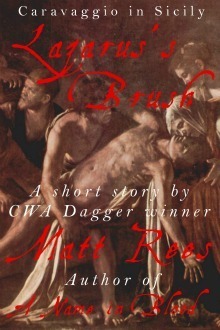

FREE Caravaggio short story download

My historical crime novel about the mysterious end of Caravaggio is out in the UK in a couple of weeks. As a taster for A NAME IN BLOOD, I'm making available a short story "Lazarus's Brush" that's also about the great Italian artist. The download is FREE until Sunday. It includes the short story, plus a sample chapter from the novel and a personal essay about how I came to write A NAME IN BLOOD. (A bit like all the extra stuff you get on a DVD, but without the "commentary" track. Maybe I'll do one of those on my Podcast some time....Well, if you do listen to the Podcast, you can hear me talking about how I wrote A NAME IN BLOOD and reading a chapter already.) In the short story "Lazarus's Brush," Caravaggio flees to Sicily with a price on his head. Commissioned to paint the raising of Lazarus, he learns about his fears of the violence that stalks him. But the story also charts a profound change in his artistic technique. It's an episode I didn't include in the novel, but it's a compelling moment in Caravaggio's life and work nonetheless. Download the US version. Get the UK edition. The Caravaggio painting at the heart of "Lazarus's Brush" has just been restored, by the way. You can read more about the restoration here.

Published on June 20, 2012 00:23

•

Tags:

art, art-history, caravaggio, crime-fiction, free-promotion, free-short-story, historical-fiction, historical-thriller, raising-of-lazarus, renaissance

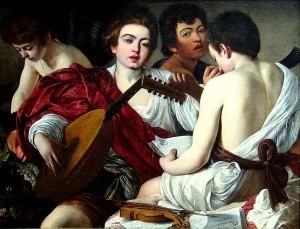

Caravaggio Masterpieces that Inspired My Novel A NAME IN BLOOD

The heart of my novel A NAME IN BLOOD, out in the UK on 5 July, is my love of Caravaggio's paintings. Though the idea for the novel comes from the Italian maestro's mysterious disappearance and death, it was these works which drew me to him. Here are some of the paintings that feature in the novel.

[caption id="attachment_2462" align="aligncenter" width="520" caption="The Calling of Saint Matthew, Church of San Luigi dei Francesi, Rome"] [/caption]

[/caption]

The three "Matthew" paintings in the French church made Caravaggio's reputation. They were his first great "history paintings," which at the time meant paintings of notable biblical scenes. His light-dark (chiaroscuro) technique is most evident in "The Calling." Many's the hour I've spent in the corner of San Luigi, feeding Euros into the light-meter so I can marvel at this work. Usually critics think Matthew is the old fellow third from left. But I think he's pointing at the youth with his head down...

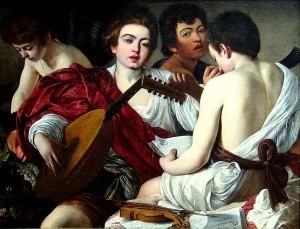

[caption id="attachment_2466" align="aligncenter" width="520" caption="The Musicians, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York"] [/caption] Young Caravaggio's self-portrait is second from the right. 1595, age 23 or 24.

[/caption] Young Caravaggio's self-portrait is second from the right. 1595, age 23 or 24.

[caption id="attachment_2467" align="aligncenter" width="520" caption="St Catherine of Alexandria, Fondacion Thyssen-Bornemisza, Madrid"] [/caption] This painting first made me fall in love with Caravaggio. I was alone with it in the room where it's housed. The saint, who's about to meet her death, seemed to watch me. I couldn't leave. It was as though I was abandoning her to her fate, so present did she seem. So I stayed a long time and...couldn't help but think about a novel... The model is Fillide, who appears in A NAME IN BLOOD.

[/caption] This painting first made me fall in love with Caravaggio. I was alone with it in the room where it's housed. The saint, who's about to meet her death, seemed to watch me. I couldn't leave. It was as though I was abandoning her to her fate, so present did she seem. So I stayed a long time and...couldn't help but think about a novel... The model is Fillide, who appears in A NAME IN BLOOD.

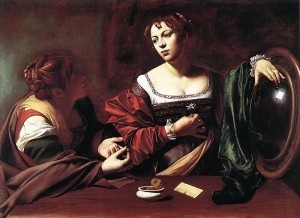

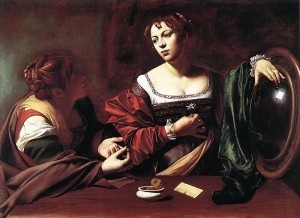

[caption id="attachment_2472" align="aligncenter" width="520" caption="Martha and Mary Magdalene, Institute of Fine Arts, Detroit"] [/caption]Fillide again, with a second woman whose beauty is so much greater for the way Caravaggio disguises her in the shadow. The convex mirror may be a clue to Caravaggio's use of projected images to help him paint.

[/caption]Fillide again, with a second woman whose beauty is so much greater for the way Caravaggio disguises her in the shadow. The convex mirror may be a clue to Caravaggio's use of projected images to help him paint.

[caption id="attachment_2473" align="aligncenter" width="520" caption="Portrait of Pope Paul V, Palazzo Borghese (private collection), Rome"] [/caption]The nasty, grasping little eyes of the Pope truly raise the hairs on the back of your neck when you're before this painting. Caravaggio was no flatterer.

[/caption]The nasty, grasping little eyes of the Pope truly raise the hairs on the back of your neck when you're before this painting. Caravaggio was no flatterer.

[caption id="attachment_2474" align="aligncenter" width="520" caption="Madonna of Loreto, Church of Sant'Agostino, Rome"] [/caption]In A NAME IN BLOOD, this is how Caravaggio sees Lena Antognetti -- the model for this Virgin -- on the doorstep of her rundown home.

[/caption]In A NAME IN BLOOD, this is how Caravaggio sees Lena Antognetti -- the model for this Virgin -- on the doorstep of her rundown home.

[caption id="attachment_2475" align="aligncenter" width="520" caption="The Rest on the Flight into Egypt, Galleria Doria Pamphilij, Rome"] [/caption]The model for the auburn-headed virgin, Anna Bianchini, died of syphilis.

[/caption]The model for the auburn-headed virgin, Anna Bianchini, died of syphilis.

[caption id="attachment_2476" align="aligncenter" width="520" caption="The Death of the Virgin, Musee du Louvre, Paris"] [/caption]Convention had the Virgin rising up to heaven with the angels. Caravaggio painted her -- Lena in this case -- as an absolutely dead woman. It looks better to us, for that reason. It also looked blasphemous to many contemporaries.

[/caption]Convention had the Virgin rising up to heaven with the angels. Caravaggio painted her -- Lena in this case -- as an absolutely dead woman. It looks better to us, for that reason. It also looked blasphemous to many contemporaries.

[caption id="attachment_2477" align="aligncenter" width="520" caption="Madonna with the Serpent, Galleria Borghese, Rome"] [/caption]For me, simply the greatest painting ever. Much of what happens in A NAME IN BLOOD was dictated by the attraction I felt to the Madonna here -- or more specifically to Lena, Caravaggio's model.

[/caption]For me, simply the greatest painting ever. Much of what happens in A NAME IN BLOOD was dictated by the attraction I felt to the Madonna here -- or more specifically to Lena, Caravaggio's model.

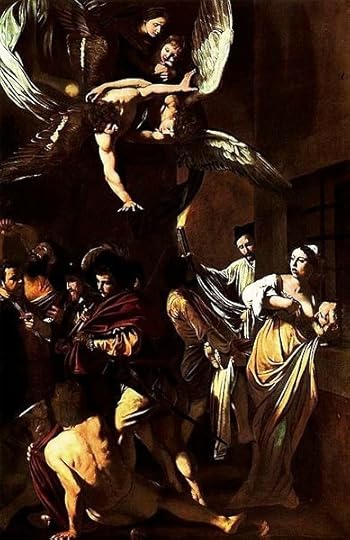

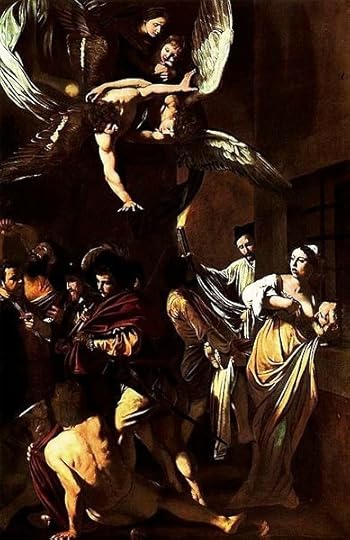

[caption id="attachment_2479" align="aligncenter" width="520" caption="Our Lady of Mercy (Seven Works of Mercy), Chapel of the Pio Monte della Misericordia, Naples"] [/caption]I stood a very long time before this painting. The street noise was loud from outside. I saw how connected Caravaggio was to ordinary people. So connected that he made them his saints and martyrs. The Madonna is, once again, Lena.

[/caption]I stood a very long time before this painting. The street noise was loud from outside. I saw how connected Caravaggio was to ordinary people. So connected that he made them his saints and martyrs. The Madonna is, once again, Lena.

[caption id="attachment_2481" align="aligncenter" width="520" caption="Portrait of Alof de Wignacourt, Musee du Louvre, Paris"] [/caption]Is this a portrait of the Grand Master or of the young boy who was his page? Caravaggio, as usual, doesn't take the traditional path.

[/caption]Is this a portrait of the Grand Master or of the young boy who was his page? Caravaggio, as usual, doesn't take the traditional path.

[caption id="attachment_2482" align="aligncenter" width="520" caption="The Beheading of St John the Baptist, Co-Cathedral of St John, Valletta, Malta"] [/caption]Standing in the cavernous oratory where this masterpiece hangs is like watching a movie unfold before you. It's a still image, yet Caravaggio captured what went before and what was to come. I believe he changed his technique to make this possible. It's central to the art story-arc of A NAME IN BLOOD.

[/caption]Standing in the cavernous oratory where this masterpiece hangs is like watching a movie unfold before you. It's a still image, yet Caravaggio captured what went before and what was to come. I believe he changed his technique to make this possible. It's central to the art story-arc of A NAME IN BLOOD.

[caption id="attachment_2484" align="aligncenter" width="520" caption="The Flagellation of Christ, Museo Nazionale di Capodimonte, Naples"] [/caption]The Flagellation is approached down a long gallery through other smaller galleries at the Capodimonte. Though you pass by masterpieces by Raphael et al, you have eyes only for this shocking, shadowy work. No artist can make everything else in a gallery seem like rubbish the way Caravaggio can.

[/caption]The Flagellation is approached down a long gallery through other smaller galleries at the Capodimonte. Though you pass by masterpieces by Raphael et al, you have eyes only for this shocking, shadowy work. No artist can make everything else in a gallery seem like rubbish the way Caravaggio can.

[caption id="attachment_2486" align="aligncenter" width="520" caption="The Denial of St Peter, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York"] [/caption]At the end, Caravaggio pushed the darkness to an extreme. Look how it lifts the most important details -- the gesture and face of Peter -- out into the light.

[/caption]At the end, Caravaggio pushed the darkness to an extreme. Look how it lifts the most important details -- the gesture and face of Peter -- out into the light.

[caption id="attachment_2488" align="aligncenter" width="520" caption="David with the Head of Goliath, Galleria Borghese, Rome"] [/caption]The most horrifying and personal of Caravaggio's biblical images. Probably the last thing he painted, while he was in Naples in 1610.

[/caption]The most horrifying and personal of Caravaggio's biblical images. Probably the last thing he painted, while he was in Naples in 1610.

[caption id="attachment_2462" align="aligncenter" width="520" caption="The Calling of Saint Matthew, Church of San Luigi dei Francesi, Rome"]

[/caption]

[/caption]The three "Matthew" paintings in the French church made Caravaggio's reputation. They were his first great "history paintings," which at the time meant paintings of notable biblical scenes. His light-dark (chiaroscuro) technique is most evident in "The Calling." Many's the hour I've spent in the corner of San Luigi, feeding Euros into the light-meter so I can marvel at this work. Usually critics think Matthew is the old fellow third from left. But I think he's pointing at the youth with his head down...

[caption id="attachment_2466" align="aligncenter" width="520" caption="The Musicians, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York"]

[/caption] Young Caravaggio's self-portrait is second from the right. 1595, age 23 or 24.

[/caption] Young Caravaggio's self-portrait is second from the right. 1595, age 23 or 24.[caption id="attachment_2467" align="aligncenter" width="520" caption="St Catherine of Alexandria, Fondacion Thyssen-Bornemisza, Madrid"]

[/caption] This painting first made me fall in love with Caravaggio. I was alone with it in the room where it's housed. The saint, who's about to meet her death, seemed to watch me. I couldn't leave. It was as though I was abandoning her to her fate, so present did she seem. So I stayed a long time and...couldn't help but think about a novel... The model is Fillide, who appears in A NAME IN BLOOD.

[/caption] This painting first made me fall in love with Caravaggio. I was alone with it in the room where it's housed. The saint, who's about to meet her death, seemed to watch me. I couldn't leave. It was as though I was abandoning her to her fate, so present did she seem. So I stayed a long time and...couldn't help but think about a novel... The model is Fillide, who appears in A NAME IN BLOOD.[caption id="attachment_2472" align="aligncenter" width="520" caption="Martha and Mary Magdalene, Institute of Fine Arts, Detroit"]

[/caption]Fillide again, with a second woman whose beauty is so much greater for the way Caravaggio disguises her in the shadow. The convex mirror may be a clue to Caravaggio's use of projected images to help him paint.

[/caption]Fillide again, with a second woman whose beauty is so much greater for the way Caravaggio disguises her in the shadow. The convex mirror may be a clue to Caravaggio's use of projected images to help him paint.[caption id="attachment_2473" align="aligncenter" width="520" caption="Portrait of Pope Paul V, Palazzo Borghese (private collection), Rome"]

[/caption]The nasty, grasping little eyes of the Pope truly raise the hairs on the back of your neck when you're before this painting. Caravaggio was no flatterer.

[/caption]The nasty, grasping little eyes of the Pope truly raise the hairs on the back of your neck when you're before this painting. Caravaggio was no flatterer.[caption id="attachment_2474" align="aligncenter" width="520" caption="Madonna of Loreto, Church of Sant'Agostino, Rome"]

[/caption]In A NAME IN BLOOD, this is how Caravaggio sees Lena Antognetti -- the model for this Virgin -- on the doorstep of her rundown home.

[/caption]In A NAME IN BLOOD, this is how Caravaggio sees Lena Antognetti -- the model for this Virgin -- on the doorstep of her rundown home.[caption id="attachment_2475" align="aligncenter" width="520" caption="The Rest on the Flight into Egypt, Galleria Doria Pamphilij, Rome"]

[/caption]The model for the auburn-headed virgin, Anna Bianchini, died of syphilis.

[/caption]The model for the auburn-headed virgin, Anna Bianchini, died of syphilis.[caption id="attachment_2476" align="aligncenter" width="520" caption="The Death of the Virgin, Musee du Louvre, Paris"]

[/caption]Convention had the Virgin rising up to heaven with the angels. Caravaggio painted her -- Lena in this case -- as an absolutely dead woman. It looks better to us, for that reason. It also looked blasphemous to many contemporaries.

[/caption]Convention had the Virgin rising up to heaven with the angels. Caravaggio painted her -- Lena in this case -- as an absolutely dead woman. It looks better to us, for that reason. It also looked blasphemous to many contemporaries.[caption id="attachment_2477" align="aligncenter" width="520" caption="Madonna with the Serpent, Galleria Borghese, Rome"]

[/caption]For me, simply the greatest painting ever. Much of what happens in A NAME IN BLOOD was dictated by the attraction I felt to the Madonna here -- or more specifically to Lena, Caravaggio's model.

[/caption]For me, simply the greatest painting ever. Much of what happens in A NAME IN BLOOD was dictated by the attraction I felt to the Madonna here -- or more specifically to Lena, Caravaggio's model.[caption id="attachment_2479" align="aligncenter" width="520" caption="Our Lady of Mercy (Seven Works of Mercy), Chapel of the Pio Monte della Misericordia, Naples"]

[/caption]I stood a very long time before this painting. The street noise was loud from outside. I saw how connected Caravaggio was to ordinary people. So connected that he made them his saints and martyrs. The Madonna is, once again, Lena.

[/caption]I stood a very long time before this painting. The street noise was loud from outside. I saw how connected Caravaggio was to ordinary people. So connected that he made them his saints and martyrs. The Madonna is, once again, Lena.[caption id="attachment_2481" align="aligncenter" width="520" caption="Portrait of Alof de Wignacourt, Musee du Louvre, Paris"]

[/caption]Is this a portrait of the Grand Master or of the young boy who was his page? Caravaggio, as usual, doesn't take the traditional path.

[/caption]Is this a portrait of the Grand Master or of the young boy who was his page? Caravaggio, as usual, doesn't take the traditional path.[caption id="attachment_2482" align="aligncenter" width="520" caption="The Beheading of St John the Baptist, Co-Cathedral of St John, Valletta, Malta"]

[/caption]Standing in the cavernous oratory where this masterpiece hangs is like watching a movie unfold before you. It's a still image, yet Caravaggio captured what went before and what was to come. I believe he changed his technique to make this possible. It's central to the art story-arc of A NAME IN BLOOD.

[/caption]Standing in the cavernous oratory where this masterpiece hangs is like watching a movie unfold before you. It's a still image, yet Caravaggio captured what went before and what was to come. I believe he changed his technique to make this possible. It's central to the art story-arc of A NAME IN BLOOD.[caption id="attachment_2484" align="aligncenter" width="520" caption="The Flagellation of Christ, Museo Nazionale di Capodimonte, Naples"]

[/caption]The Flagellation is approached down a long gallery through other smaller galleries at the Capodimonte. Though you pass by masterpieces by Raphael et al, you have eyes only for this shocking, shadowy work. No artist can make everything else in a gallery seem like rubbish the way Caravaggio can.

[/caption]The Flagellation is approached down a long gallery through other smaller galleries at the Capodimonte. Though you pass by masterpieces by Raphael et al, you have eyes only for this shocking, shadowy work. No artist can make everything else in a gallery seem like rubbish the way Caravaggio can.[caption id="attachment_2486" align="aligncenter" width="520" caption="The Denial of St Peter, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York"]

[/caption]At the end, Caravaggio pushed the darkness to an extreme. Look how it lifts the most important details -- the gesture and face of Peter -- out into the light.

[/caption]At the end, Caravaggio pushed the darkness to an extreme. Look how it lifts the most important details -- the gesture and face of Peter -- out into the light.[caption id="attachment_2488" align="aligncenter" width="520" caption="David with the Head of Goliath, Galleria Borghese, Rome"]

[/caption]The most horrifying and personal of Caravaggio's biblical images. Probably the last thing he painted, while he was in Naples in 1610.

[/caption]The most horrifying and personal of Caravaggio's biblical images. Probably the last thing he painted, while he was in Naples in 1610.

Published on June 22, 2012 04:22

•

Tags:

a-name-in-blood, art, art-history, caravaggio, crime-fiction, historical-fiction

Writing with Paint: Learning Oils for My Caravaggio Novel 'A Name in Blood'

To research A Name in Blood, my novel about the mystery of Caravaggio’s death, I traveled to all the places where the great artist lived and worked. I visited galleries around the world to stand before his masterpieces, and I read scores of books about him and the period in which he lived. (I don’t expect praise for this; it was no sacrifice, because most of the research was carried out in Italy. It’s a bit like saying, "I had to have sex with a lot of beautiful women to write this book." Except that my wife came with me to do the research, so it only involved one beautiful woman.)

To research A Name in Blood, my novel about the mystery of Caravaggio’s death, I traveled to all the places where the great artist lived and worked. I visited galleries around the world to stand before his masterpieces, and I read scores of books about him and the period in which he lived. (I don’t expect praise for this; it was no sacrifice, because most of the research was carried out in Italy. It’s a bit like saying, "I had to have sex with a lot of beautiful women to write this book." Except that my wife came with me to do the research, so it only involved one beautiful woman.)But none of this would’ve been worth a damn if, when it came to write about Caravaggio at work, I hadn’t had some idea of how to create a painting out of oils.

Trouble was, when I started my research, that was exactly where things stood. In fact, I was pretty sure I couldn’t draw at all.

My brother Dom got the talent with the paint brush in our family, I thought. Inherited from my Dad, who’s an architect and a fine caricaturist. Dom studied fine art and teaches art at a school in London. I was certain that old Mrs. Coneybear, my ludicrously named, Joyce Grenfell-like high school art teacher, had been correct when she glanced over my sketches midway through class and said, “I think you’d better model for the other pupils today, Rees.”

Still, never write anyone off, Mrs. Coneybear. My sister turns out to be rather a good painter, and my mother just made a clay model that looks exactly like the Picasso on which she modeled it. So evidently the whole family has it in them.

Because while I didn’t manage to match Caravaggio (needless to say, that wasn’t my goal), I did find intense pleasure in the concentration and delicacy and even the little tricks needed to paint in oils.

My friend Yael Robin, whose fabulous installations have been shown at the Israel Museum among other fine locations, gave me a few lessons. She emphasized drawing to begin with. I found I wasn’t quite awful, but I knew there was no great talent there.

My friend Yael Robin, whose fabulous installations have been shown at the Israel Museum among other fine locations, gave me a few lessons. She emphasized drawing to begin with. I found I wasn’t quite awful, but I knew there was no great talent there.So we soon moved onto the important stuff. Oils. It transpires that oils are, in may ways, easier than pen and ink, because they’re more forgiving. Draw the wrong line with a pen and it shall remain wrong. Do it with oils and you can scrape it away or smudge it.

In fact, there’s a parallel between oils versus pen and the way I play music. I’ve never been particularly good at playing exactly what’s written on a page of music. I prefer to play in a way that improvises around that musical text. It means I’m not much use at the exactitude of classical music. I don’t much go for the endlessly repeated rock guitar riff either. But I love to diddle around with the notes and make something that’s always new. So too with oils. They’re built up slowly and unless you’re trying to make a photographic representation of something there’s a good deal of leeway with color and line. There’s also time to savor the scent of the linseed oil and turpentine in the room.

That may be why I love Caravaggio’s later works so much. He had moved away from the precision of his earlier pieces. His work reflected his life on the run, but also, I think, the way he felt about life and the soul. Essentially he was painting light, and light often comes at us broken down and inexact.

As you'll see from the examples of my work here (and more I intend to post tomorrow), I made some inexact and broken down (though only in the positive sense of the term!) copies of details from Caravaggio’s works. I’m quite sure A Name in Blood is better for that. I know that I am.

Published on June 25, 2012 04:39

•

Tags:

art, art-history, caravaggio, crime-fiction, historical-fiction, painting, renaissance