Matt Rees's Blog - Posts Tagged "martin-cruz-smith"

Stealing the novel

If there’s one thing that authoring a series of novels will teach you, it’s that you can’t wait for inspiration. But you can prompt it, give it little electric shocks that’ll keep it bubbling within you. Here are a few methods I use to do that.

If there’s one thing that authoring a series of novels will teach you, it’s that you can’t wait for inspiration. But you can prompt it, give it little electric shocks that’ll keep it bubbling within you. Here are a few methods I use to do that.I go to the places I’m writing about. I talk to people who might be similar to (or even the basis for) my characters. I read about them and their world. I engage in the same activities in which they specialize. But I also read about entirely different subjects – so long as they’re extremely well-written.

Some of these ideas sound self-evident. I’ve written a series of Palestinian crime novels, so it stands to reason that I’ve spent the last decade and a half in Gaza, Bethlehem, Nablus, Jerusalem, tasting and smelling and talking and looking. I even force myself to read the drivel that gets written about this place in journalism and nonfiction—occasionally I come across something good, but mainly it just gets me down. How many times can you listen to a mediocre pop song? Well, that’s how most Middle East journalism sounds in my ear.

For a novel I have coming out next year about Mozart, I learned to play the piano. I learned that I wasn’t much good at it, but I also saw inside the music in a way I couldn’t have done merely by listening.

Not so obvious, however, might be the wide reading. A number of writers I’ve met or read about say they don’t have time to read anything that isn’t directly related to their research. In other words, if I’m writing about Berlin, it’s goodbye to Raymond Chandler for the next 12 months.

Well, T.S. Eliot wrote that “Immature poets imitate; mature poets steal.” I can look back at my literary efforts as an undergraduate and see what imitation there was throughout all of it. Now I’m mature (I try to fight it; I work out; but I concede, I’m maturing…) and I’ve figured out how to steal.

What Eliot meant was that it takes a while, as a writer, to realize how to make things your own. That means going beyond the plagiaristic imitation of youth, which is humble and filled with homage, to the confident sense that whatever you see another writer do, you can do it better. Then when you read something good, it doesn’t appear in your work as the same thing—it spurs you to develop your own spin on the thought that’s provoked in you by what you’ve read.

Let me give you an example. I challenge any one of you to show me a contemporary writer who can build a character in a fuller, more convincing manner than Hilary Mantel, who won the Booker Prize last year for her masterful “Wolf Hall.” If anything, her 1992 classic “A place of Greater Safety,” a novel about the French Revolution, is even more amazing than her now-famous prize-winner.

“Greater Safety” tells the story of the entire revolution through the characters of Robespierre, Danton and Desmoulins. From their childhoods to (it’s a historical novel so I don’t have to give any spoiler alerts) their executions. Each of them is built slowly, and we see their character arc in a way that even they don’t—watch their idealism tainted with violence, until it turns on them. Because we take that journey with them, we care more deeply for them, even as they become murderous and unjust.

The “stealing” comes in whenever I see a point that Mantel uses to build that empathy. Robespierre, we learn, always carries a tiny copy of Rousseau in his pocket. Some time later it’s on his desk and Desmoulins notices it. Just one sentence. A couple hundred pages later someone quotes Rousseau against him and only his close friends understand that he’s entirely defeated. We know he’s a man who has bent principles for his friend Desmoulins, but he can’t desert them completely. It’s a choice between Desmoulins, whom he loves, or the book that he keeps close to his heart. Books always win in contests like that.

That doesn’t make me want to replicate the exact same thing in my next book – that’s what I might’ve tried when I was 19. Instead, I think of ways in which to send a signal to the reader. To plant an object that inspires a character, that takes them on the path on which we follow them in the novel. Until ultimately it underlies their collision with another character; makes compromise an impossible undermining of everything they believe about themselves.

That’s stealing, and it’s a good thing to do.

You can find such moments in the small factoids of history books, if you’re researching a period, or in nonfiction. It’s in poems, where a phrase about a frieze on an urn (“Thou still unravished bride of quietness”) will spark a thought about your memories of your own wedding or of a sexual exploit which you can use for a character in your book.

A writer whose obvious focus is character would be the most direct place to start. In other words, not the kind of ultra-bland snoozing that appears in the short fiction of The New Yorker, which always seems to be written as though it were designed to mimic a relatively dull person telling you a story in a cocktail party or at the counter of a bodega.

Choose something with sweep, like Mantel. Someone with an eye for a mordant detail, like Graham Greene in “The Honorary Consul.” Someone who shows you an entire, devastated culture through the eyes of one man, like Martin Cruz Smith’s investigator Arkady Renko.

A novel’s like a marathon. Stop and sit down at the side of the road and no amount of sprinting will get you to the finish line. You have to write every day and once you’re started you can’t stop. “Stealing” is a way of warming up for the long run.

Published on April 15, 2010 00:12

•

Tags:

a-place-of-greater-safety, berlin, bethlehem, booker-prize, crime-fiction, danton, desmoulins, gaza, graham-greene, hilary-mantel, historical-fiction, israel, jerusalem, martin-cruz-smith, middle-east, mozart, nablus, novels, palestine, raymond-chandler, robespierre, t-s-eliot, wolf-hall, writing

Renko Rules

This is a crime fiction blog. So we ought to shoot straight. Here it is: there are lots of crappy detective novels out there. Which is why I say thank God for Arkady Renko.

This is a crime fiction blog. So we ought to shoot straight. Here it is: there are lots of crappy detective novels out there. Which is why I say thank God for Arkady Renko.The hero of Martin Cruz Smith’s excellent series set in the Soviet Union and, later, Russia (with stops in Cuba, Ukraine, Germany and Alaska) is the closest today’s crime fiction gets to Chandler’s idea that “down these mean streets a man must go who is not himself mean.” In many ways, Cruz Smith is the closest among current crime writers to the keen yet elliptical style of plot development perfected by Chandler. (In Chandler’s case, that was, as

he admitted, largely because he didn’t really keep track of the plot; I

suspect that’s not the issue with Cruz Smith.)

[Note: To qualify my lead paragraph, I ought to quote Chandler once again:

“There are as many bad literary novels as bad detective novels. The bad

literary novels just don’t get published.” That’s not true anymore, as

anyone who’s ever tossed a copy of Philip Roth’s “The Plot Against America”

at the wall will vouch. Still detective fiction retains that reputation among certain circles, and indeed a lot of crap still washes through the sleuthing sluices.]

I’ve read all the Renko novels, as well as some of Cruz Smith’s standalone

books. From the perspective of a writer, I’ve observed with enormous

pleasure the elements that make Renko work so well, and of course the

manner in which Cruz Smith puts them to effect.

A key to this is Renko’s voice. His apparently deep disillusion is something of a trick. Renko’s father was a Stalinist general and as an investigator he’s constantly measuring himself against that old bastard – and regretting the similarities he finds. This continuity between the old USSR and the new FSU grounds Renko. It’s why he’s not a drunk like some of his colleagues, and why he isn’t corrupt like the others: he’s a hard-edged idealist, like his father, who happens to have inherited the humanity of his mother.

Cruz Smith’s Russia is the perfect backdrop for Renko’s tawdry shining

armor. After the collapse of the Soviet Union, Cruz Smith has painted the

breakdown of society better than any nonfiction or journalism I’ve read.

It’s what I’ve tried to do with my Palestinian crime novels.

Read more of this post on my blog The Man of Twists and Turns.

Published on November 17, 2011 05:38

•

Tags:

arkady-renko, crime-fiction, martin-cruz-smith, russia, soviet-union, writing

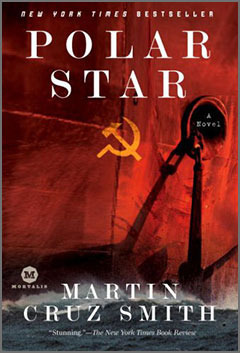

If you read only one Martin Cruz Smith, read Polar Star

Isolated on an arctic ship, Cruz Smith’s detective is even more heroic

What? If you read only one thriller by Martin Cruz Smith, it's not Gorky Park, one of the biggest hit thrillers of the last 40 years and the basis of that great movie with William Hurt? No, not even one of Martin Cruz Smith’s books set in Moscow. Polar Star is the Cruz Smith novel with the greatest tension and the biggest challenges to his hero, Arkady Renko.

What? If you read only one thriller by Martin Cruz Smith, it's not Gorky Park, one of the biggest hit thrillers of the last 40 years and the basis of that great movie with William Hurt? No, not even one of Martin Cruz Smith’s books set in Moscow. Polar Star is the Cruz Smith novel with the greatest tension and the biggest challenges to his hero, Arkady Renko.

After Gorky Park, Renko goes into self-imposed exile gutting fish in the frozen Arctic Ocean. On the creaking Polar Star he uncovers a murder that becomes a bigger conspiracy. By putting Renko on the isolated ship, Cruz Smith highlights his heroic and honorable qualities. The same traits he showed in Gorky Park and which have carried him marvelously through six subsequent novels.

After Gorky Park, Renko goes into self-imposed exile gutting fish in the frozen Arctic Ocean. On the creaking Polar Star he uncovers a murder that becomes a bigger conspiracy. By putting Renko on the isolated ship, Cruz Smith highlights his heroic and honorable qualities. The same traits he showed in Gorky Park and which have carried him marvelously through six subsequent novels.

Cruz Smith has some wonderful Renko novels. Which is your favorite? Let me know.

Click to get a FREE ebook of my crime stories.

What? If you read only one thriller by Martin Cruz Smith, it's not Gorky Park, one of the biggest hit thrillers of the last 40 years and the basis of that great movie with William Hurt? No, not even one of Martin Cruz Smith’s books set in Moscow. Polar Star is the Cruz Smith novel with the greatest tension and the biggest challenges to his hero, Arkady Renko.

What? If you read only one thriller by Martin Cruz Smith, it's not Gorky Park, one of the biggest hit thrillers of the last 40 years and the basis of that great movie with William Hurt? No, not even one of Martin Cruz Smith’s books set in Moscow. Polar Star is the Cruz Smith novel with the greatest tension and the biggest challenges to his hero, Arkady Renko. After Gorky Park, Renko goes into self-imposed exile gutting fish in the frozen Arctic Ocean. On the creaking Polar Star he uncovers a murder that becomes a bigger conspiracy. By putting Renko on the isolated ship, Cruz Smith highlights his heroic and honorable qualities. The same traits he showed in Gorky Park and which have carried him marvelously through six subsequent novels.

After Gorky Park, Renko goes into self-imposed exile gutting fish in the frozen Arctic Ocean. On the creaking Polar Star he uncovers a murder that becomes a bigger conspiracy. By putting Renko on the isolated ship, Cruz Smith highlights his heroic and honorable qualities. The same traits he showed in Gorky Park and which have carried him marvelously through six subsequent novels.Cruz Smith has some wonderful Renko novels. Which is your favorite? Let me know.

Click to get a FREE ebook of my crime stories.

Published on March 17, 2014 00:56

•

Tags:

crime-fiction, gorky-park, if-you-read-only-one, martin-cruz-smith, polar-star, russia, thrillers, writing