Matt Rees's Blog - Posts Tagged "memoir"

Mother and Son, Wars and Recipes

War correspondent Matt McAllester fled into the fields of battle to escape an alcoholic, mentally ill mother. In his memoir, Bittersweet, he tries to make amends with her, in the kitchen. Read my interview with McAllester on The Daily Beast.

Published on May 22, 2009 05:21

•

Tags:

alcoholic, bittersweet, dailybeast, intifada, journalism, mcallester, memoir, war

The Real Iraq War: Michael Anthony’s Writing Life

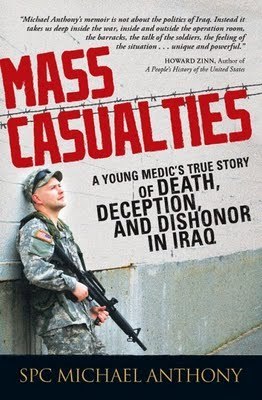

By now it’s no secret that the Iraq War has been a disillusioning experience for many of the U.S. servicemen sent there. The literature on the war has, so far, been mostly written by journalists. There’s plenty of it, and like most journalism it runs pretty mainstream and inoffensive, no matter how bloody the scenes depicted. But Michael Anthony, a veteran of the war, has a different perspective. His new book Mass Casualties: A Young Medic’s True Story of Death, Deception, and Dishonor in Iraq is the best account yet of a war that continues to cost lives and to sully the image of the democracy in whose name it was supposedly fought. It’s a subject I’ve thought about a great deal as I travel my corner of the Middle East and as I continue to encounter fighters – Israeli and Palestinian – who endure personal hardship and tormenting nightmares when they face the realities of war. So read the book. Meantime, here's Michael's Writing Life.

By now it’s no secret that the Iraq War has been a disillusioning experience for many of the U.S. servicemen sent there. The literature on the war has, so far, been mostly written by journalists. There’s plenty of it, and like most journalism it runs pretty mainstream and inoffensive, no matter how bloody the scenes depicted. But Michael Anthony, a veteran of the war, has a different perspective. His new book Mass Casualties: A Young Medic’s True Story of Death, Deception, and Dishonor in Iraq is the best account yet of a war that continues to cost lives and to sully the image of the democracy in whose name it was supposedly fought. It’s a subject I’ve thought about a great deal as I travel my corner of the Middle East and as I continue to encounter fighters – Israeli and Palestinian – who endure personal hardship and tormenting nightmares when they face the realities of war. So read the book. Meantime, here's Michael's Writing Life.How long did it take you to get published?

I started writing the book as soon as I returned home from Iraq. I wrote the first hundred pages in six months and then the last hundred pages in two days (for the first draft). I then spent several months editing and doing rewrites. In total, from starting to write until getting a book deal, it took one year (almost exactly).

Would you recommend any books on writing?

I’m sure there are some out there, but I’ve never read any books on writing. I can give you a few of my favorite books though; the ones that I place as the top tier of writing, and for me, I think reading books, with a great style and prose, can help your writing as well. My top books (not in any order): Atlas Shrugged, Catch 22, Catcher in the Rye, The Perks of Being a Wallflower.

What’s a typical writing day?

I usually spend my typical writing day, finding other things to do than write. I think part of the aspect of being a writer is having the discipline to actually sit down and write. I don’t write every day as most writers do, but when I do write, that’s all I do. For me, it’s not about quantity of time, but quality of time. I could write while doing laundry or watching television, but it wouldn’t be the same. When I do write, it’s all about the writing and nothing else, I throw myself into and sometimes I won’t shower or leave the house for days.

Plug your book. What’s it about? Why’s it so great?

My latest and first book is: Mass Casualties: A Young Medic’s True Story of Death, Deception, and Dishonor in Iraq. It is the true story of what goes on during war, and what went on over there. It’s not a pro war or anti war book, it’s simply a true war story. I think a lot of stories/movies/shows out there; paint this picture of the American Soldier as this romanticized heroic idea. What I wanted to do with my book was simply paint a picture of the American Soldier as a human. It goes back to the old saying: “I’d rather be hated for what I am, than loved for what I’m not.” If people really want to appreciate and support the troops, the least they can do is learn the real stories, and not just the ones they’re told by reporters or the military officials.

If you look at a majority of war books or movies out there, they all paint this perfect picture of war and its effects. For example, look at one of the long running war movie franchises: Rambo, starring Sylvester Stallone. Rambo goes off to war and comes home with severe post-traumatic stress disorder. Even with this PTSD, he still manages to be a hero, save a town or city from some disaster and at the end, still get the girl. But in reality, if a soldier comes home with severe PTSD, they kill themselves. End of movie, roll the credits.

The problem with romanticizing these soldiers and situations is that when they come home, no one understands what they went through and what it was really like. And because of this, today’s military has the highest suicide rates in thirty years. Since the Afghanistan war started, more active duty soldiers have killed themselves than have been injured or killed in Afghanistan—combined. This is why I think we need to give people the full picture of war, and not just the good stuff they want to know about.

Who’s the greatest stylist currently writing?

My current, favorite, contemporary writer is: Stephen Chbosky, author of: The Perks of Being a Wallflower. For me, I just loved everything about that book, from the idea of it, to the way it was written.

How much research was involved in your book?

The vast majority of my book was based on my journals in Iraq, and because of this, the research involved was minimal. All I had to do was convert my illegible sometimes chaotic journal entries, into readable prose.

What’s the best idea for marketing a book you can do yourself?

Tell everyone you know, or have ever known, and then tell them to tell everyone they know. I now think everyone in my high-school class knows I have a book in bookstores. Social Media is a great thing, and don’t be afraid to go out there and use it. Also, I think getting other authors to review and/or comment on your work. I was able to get over thirty well accomplished people to review, comment on, and endorse my work; from famous politicians, to famous historians, psychologists, veterans and authors.

How many books did you write before you were published?

When I was sixteen I had written three books and two movies; it then took me five years to realize I wanted to be a writer.

What’s your weirdest idea for a book you’ll never get to publish?

When I was younger, I once wrote a book from the perspective of a T-shirt. The book had a T-shirt as a main character and I followed him around and wrote about what he was thinking as the wearer of the shirt went around and did his daily duties.

No more Mister Nice Guy

This is where it gets ugly.

Last week I zapped off the manuscript of my new novel to my agent in New York. My wife told me to get working on the next book. It’s not because she’s worried about me slacking off and failing to pay the rent. No, it’s because she knows what happens when I’m not writing.

Ever read “The Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde”? When I’m writing, I’m Dr Jekyll. All my unloveable urges are intellectualized and subsumed to a pleasure in the creative impulse. As soon as I stop writing, I shuffle about the apartment like Mr Hyde, hunched and suspicious, leering, weak-willed and a bit vicious.

It happens every time I finish a book and I’ve dealt with it on each occasion with a different degree of success. This time I’ve gone straight into the documentary research for my next book, which will be a historical novel. Even so, over the weekend I was conscious that the calm I feel when writing was leeching away. My teeth were on edge. I yelled at a motorist (admittedly he’d failed to stop when my son and I were on the crosswalk in front of him, but nonetheless…). I went a couple of days without shaving and, though I didn’t knock over any small girls standing on the street corner, I did start to think I was degenerating into a vulpine Hyde.

I turned to Robert Louis Stevenson’s classic and found this:

“Between these two, I now felt I had to choose. … My two natures had memory in common, but all other faculties were most unequally shared between them.…Strange as my circumstances were, the terms of this debate are as old and commonplace as man; much the same inducements and alarms cast the die for any tempted and trembling sinner; and it fell out with me, as it falls with so vast a majority of my fellows, that I chose the better part and was found wanting in the strength to keep to it.”

What makes Stevenson’s tale great (in its original, non-Hollywood form) is that he nailed so clearly the dilemma at the heart of every civilized man. Freud wrote that man fights wars because we can only bear the restraint and repression of civilization for so long, before we blow. In my case, I write novels for the same reason.

As a writer, I have to be closer to my emotions perhaps than anyone except a shrink. The emotions need to be close enough to the surface that I can put them into sentence form and into the mouths of characters on the page.

If I was an accountant I wouldn’t need to do that every day. So I’d probably let it go.

I’ve realized that the annual post-completion jitters and self-doubt is merely what happens when I feel the strain of repressing those emotions. When I’m writing I don’t have to tamp them down – in fact, the opposite, I tease them out and give them form. Between books, I have to fight them because there’s nowhere for them to go. (It’s a little bit like Manhattan in August when all the analysts take their holiday. Everyone breaks down and blames the heat, but it’s really that they have nowhere to unload their neuroses.)

So long as I know what’s going on, I know that I won’t really turn into Mr Hyde. Not often, anyway.

(I posted this first on International Crime Authors Reality Check, a group blog with other crime authors Christopher G. Moore, Barbara Nadel and Colin Cotterill. Take a look.)

Last week I zapped off the manuscript of my new novel to my agent in New York. My wife told me to get working on the next book. It’s not because she’s worried about me slacking off and failing to pay the rent. No, it’s because she knows what happens when I’m not writing.

Ever read “The Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde”? When I’m writing, I’m Dr Jekyll. All my unloveable urges are intellectualized and subsumed to a pleasure in the creative impulse. As soon as I stop writing, I shuffle about the apartment like Mr Hyde, hunched and suspicious, leering, weak-willed and a bit vicious.

It happens every time I finish a book and I’ve dealt with it on each occasion with a different degree of success. This time I’ve gone straight into the documentary research for my next book, which will be a historical novel. Even so, over the weekend I was conscious that the calm I feel when writing was leeching away. My teeth were on edge. I yelled at a motorist (admittedly he’d failed to stop when my son and I were on the crosswalk in front of him, but nonetheless…). I went a couple of days without shaving and, though I didn’t knock over any small girls standing on the street corner, I did start to think I was degenerating into a vulpine Hyde.

I turned to Robert Louis Stevenson’s classic and found this:

“Between these two, I now felt I had to choose. … My two natures had memory in common, but all other faculties were most unequally shared between them.…Strange as my circumstances were, the terms of this debate are as old and commonplace as man; much the same inducements and alarms cast the die for any tempted and trembling sinner; and it fell out with me, as it falls with so vast a majority of my fellows, that I chose the better part and was found wanting in the strength to keep to it.”

What makes Stevenson’s tale great (in its original, non-Hollywood form) is that he nailed so clearly the dilemma at the heart of every civilized man. Freud wrote that man fights wars because we can only bear the restraint and repression of civilization for so long, before we blow. In my case, I write novels for the same reason.

As a writer, I have to be closer to my emotions perhaps than anyone except a shrink. The emotions need to be close enough to the surface that I can put them into sentence form and into the mouths of characters on the page.

If I was an accountant I wouldn’t need to do that every day. So I’d probably let it go.

I’ve realized that the annual post-completion jitters and self-doubt is merely what happens when I feel the strain of repressing those emotions. When I’m writing I don’t have to tamp them down – in fact, the opposite, I tease them out and give them form. Between books, I have to fight them because there’s nowhere for them to go. (It’s a little bit like Manhattan in August when all the analysts take their holiday. Everyone breaks down and blames the heat, but it’s really that they have nowhere to unload their neuroses.)

So long as I know what’s going on, I know that I won’t really turn into Mr Hyde. Not often, anyway.

(I posted this first on International Crime Authors Reality Check, a group blog with other crime authors Christopher G. Moore, Barbara Nadel and Colin Cotterill. Take a look.)

Episodes in the Literary Life 1: My Part in Salman Rushdie's Peril

(Readers often write to ask me how I came to be an author. Over the coming weeks, I shall be writing a series of autobiographical vignettes which shall, I believe, demonstrate the mélange of neuroses, ambition, talent, chance, mischance, place, and alcohol that goes toward the creation of a writer. This one, at least. The tales may be instructive or proscriptive.)

(Readers often write to ask me how I came to be an author. Over the coming weeks, I shall be writing a series of autobiographical vignettes which shall, I believe, demonstrate the mélange of neuroses, ambition, talent, chance, mischance, place, and alcohol that goes toward the creation of a writer. This one, at least. The tales may be instructive or proscriptive.)Writers ought not to think identically with most of the people around them.

It usually comes quite easily to me. For example, when Ayatollah Khomeini

announced his fatwa on Salman Rushdie, I thought: “Serves you right for

looking down your nose at me, you smug sod.”

Ordinarily I’d have very little in common with the unlamented (by me, anyway) Ayatollah. However, in this case, he happened to catch me at the

right time. The previous night I had experienced Rushdie’s disdain. I wouldn’t blame Salman, because I was drunk at the time and a bit rude. Except that I was at an age when I blamed other people for everything. So, yes, I blamed him.

It was February 1989 and I was in my first reporting job at United Press

International, a once-mighty newswire which now has considerably less

influence than even a dead Khomeini. I had written a few stories about the

growing controversy around Rushdie’s novel “The Satanic Verses.” British

Muslims had burned the book for its supposedly blasphemous portrayal of

Muhammad. The novel was up for the Whitbread Book Award, one of Britain’s

premier prizes. My bureau chief suggested I attend the awards dinner.

Having written a story in which Rushdie won (as everyone expected) and left

it at the newsdesk, I went off to the Barbican for the dinner. I needed only to gather a couple of quotes from Rushdie when he won, so that I might phone them in and have an editor plug them into my story. So I decided I was free to otherwise enjoy the evening.

Imagine a 22-year-old youth from a less than sumptuously endowed background who finds himself placed at a press-table laden with better food than his mother cooks for him and free red wine. He is seated between two lovely and solicitous public relations ladies who laugh at his jokes, wear low-cut evening dresses, and who, he imagines, appear to find him sexually

irresistible. What would you have done?

Well, I acted unprofessionally. I became quite drunk and raucous. This failed to impress the BBC correspondent across the table, or the other bored hacks waiting to file their “Rushdie triumphs in face of controversy” stories.

Late in the evening when the judges arose to pronounce the winner, I was

giggling into the neck of one of the patient p.r. girls.

“And the winner is…”

I nuzzled. She giggled. Patiently.

“…Paul Sayer, for ‘The Comforts of Madness.’”

“Oh, fuck!” The applause was rapturous, so people more than two tables away probably didn’t hear me curse.

Paul Sayer spoke engagingly of his joy at winning. At least I gather he did. I was occupied, telling the p.r. ladies I couldn’t believe “fucking Rushdie didn’t fucking win.” As Sayer left the podium, I leaned across to the BBC man and said, “What did that fucker say?” He recited a quick quote for me.

I stumbled down the stairs to the press room. (Why would you serve journalists free wine and then put the press room down two flights of stairs?) I phoned my bureau chief. “Karin, fucking Rushdie didn’t fucking win. Fuck it.” She inquired, with considerable amusement in her voice, if I had obtained a quote from “fucking Rushdie” or from the judges.

I labored up the stairs to the hall and barreled to the front tables, where I ignored the ebullient Paul Sayer and headed for Rushdie. He lingered beside his table, standing with his second wife, an author whose work I had not then read, Marianne Wiggins. (I still haven’t read it.)

Rushdie was otherwise alone. I assume all the sober or less drunk hacks had

by now obtained their quotes and were filing their stories. As I reached

Rushdie, I noted that I appeared to be unable to stand straight. Or to talk.

I managed to ask him, “Are you happy about the fuss over your book, because it’ll help sales?” (I was 22. If you weren’t crass at 22, then I pity you.)

Rushdie looked at me with amused contempt –– amused, because he saw that he would be afforded an opportunity for a bon mot. I didn’t manage to write down the bon mot and I don’t remember what it was. It amounted to: “I’d prefer to have lower sales and not to have the controversy.” He turned to his wife and gave her a little hiccup of smug amusement which went like this: “Hah-hnh.” I remember that. Word for word.

“Hah-hnh-hnh,” said Marianne Wiggins. (From what I know of her novels, she

sometimes writes like that, too.)

In that moment I conceived a great hatred of Rushdie. An unwarranted

hatred, much like my mother’s aversion to mustachioed men. But a hatred

nonetheless.

I shuffled to the next table. Two of the judges stood there. I approached them. They were both Conservative cabinet members. Douglas Hurd was Foreign Secretary (He later became Lord Westwall, which sounds to me like a frozen foods conglomerate). Kenneth Baker was Education Minister (He’s now Baron Baker of Dorking, which is surely a title concocted by unimaginative satirists). Both appeared to be extremely tall. Or I was getting closer to the ground as Rushdie’s “hah-hnh” rang in my ears.

“Why’d you vote for Rushdie to win?” I slurred.

The two ministers shared a look they must have picked up from studying Mrs.

Thatcher in a bad mood. “Actually I rather preferred the Tolstoy book,” said Hurd. (A.N. Wilson’s excellent biography of Tolstoy was also shortlisted for the prize.)

I tripped to the press room. By the time I had managed to decipher my meager notes and dictate them to the newsdesk, the Underground had stopped running. I spent the night on a bench outside the Barbican tube station. Without a coat. My shirt sweaty from the alcohol and the humiliation. In London. In February.

The next day, as I sat at the newsdesk, a story came through about Khomeini’s fatwa. Grimacing through my hangover at the ticking newswire, I pondered the notion of karma, developed in Rushdie’s ancestral land. It had struck. “Don’t mess with me,” I thought. “Hah-hnh.”

Published on February 23, 2012 02:13

•

Tags:

ayatollah-khomeini, memoir, salman-rushdie, the-satanic-verses

Episodes in the Literary Life 2: Get Me to Fucking Manhattan

(This continues my series of autobiographical vignettes, intended to demonstrate the neuroses, ambition, talent, chance, mischance, place, and alcohol that go toward the creation of a writer. The tales may be instructive or proscriptive. This one, at least, is mainly about the alcohol part.)

(This continues my series of autobiographical vignettes, intended to demonstrate the neuroses, ambition, talent, chance, mischance, place, and alcohol that go toward the creation of a writer. The tales may be instructive or proscriptive. This one, at least, is mainly about the alcohol part.)I quit drinking the day after I turned 27. On my birthday, my girlfriend threw me a surprise drinking party. I certainly surprised her. I ruined our relationship with my behavior and nearly fell off the roof of a twelve-story apartment block on New York’s Upper West Side. Still I remain amazed that I waited so long to hang up my beer mug.

After all, in the preceding few months I had blacked out on the Subway a number of times late at night and come around in what can only be described as some of the nastiest neighborhoods in the city.

The first blackout was disconcerting. I was on my way home from Greenwich Village. I nodded out on the A-Train and found myself at the end of the line, at Manhattan’s northernmost tip, way above Harlem. I checked my pockets, wondering how I had slept through 200 city blocks after midnight without being robbed. I immediately traversed the station and made my way to the Downtown platform, wondering when one of the African-Americans (for all the other passengers in the station appeared to be of that ethnicity) was going to jump me.

When the train eventually got rolling, I found myself seated across the aisle from the only other white guy on the train. He, too, had reached Washington Heights because he was too drunk to find his stop. Unfortunately he wasn’t sobering up nearly as fast as me.

Swaying with the train, he engaged me in slurred conversation about the former mayor, David Dinkins, who he described repeatedly as “a Jew nigger.” I made a tactical error, when I demonstratively attempted to correct him by saying that Dinkins was not a Jew. “Or….the other thing, either,” I added, with haste.

The drunk became irascible on the issue, then fell asleep.

As did I the following weekend on the 2-Train. I awoke at 110th Street Station in Harlem. But I didn’t know it.

This time, you see, I was so drunk that not even fear of a mugging could sober me up. In fact, I was like the fighting drunk who aggressively seeks out the very fists against which he could have no possible defense.

I stormed up to the token booth (probably I weaved on shaky legs, but I felt as though I was storming) and handed over the pittance that was then required to ride the Subway. I inquired of the African-American token clerk which platform would take me back to Manhattan. You see, I assumed I had slept right to the end of the line once more. All the way to the Bronx.

“You in Manhattan, man,” he replied.

“Oh, for fuck’s sake,” I raged, impatient to be in my bed, where I wouldn’t be able to fall over. “I want to get out of the Bronx. Which way is Manhattan?”

“You in Manhattan,” he said, with some exasperation.

“I want to get to fucking Manhattan. Get me to fucking Manhattan.”

The clerk shook his head and gestured for the stairs leading to the Downtown line. He had evidently translated my drunken rant as “Get me to where the white people are.”

Surprisingly, once more I was subject to no violence or rapine. In fact, I feel a lot more threat on the streets of my hometown in Wales on a Saturday night than I ever did in the so-called slums of New York. Moreover these incidents convinced me that the nastiest people in New York all congregate downtown and earn millions of dollars a year. But that’s for another episode…

(By the way, Robert Burton wrote that “Diogenes struck the father when the son swore.” So if anyone doesn’t like the use of the f-word in this post, I suggest you get in touch with David Rees of Newport, Monmouthshire. He’s on fucking Facebook.)

Right Now, You're Gibernau

(This continues my series of autobiographical vignettes, intended to demonstrate the neuroses, ambition, talent, chance, mischance, place, alcohol and attitude that go toward the creation of a writer. The tales may be instructive or proscriptive. This one concerns identity.)

(This continues my series of autobiographical vignettes, intended to demonstrate the neuroses, ambition, talent, chance, mischance, place, alcohol and attitude that go toward the creation of a writer. The tales may be instructive or proscriptive. This one concerns identity.)In a communal-style dining room in the Sicilian town of Siracuse, my wife noticed that I was being ogled by a bashful fellow in a white apron. Before I could figure out why a twenty-year-old, chubby Italian would be smiling, wistful and excited, in my direction, the owner of the joint approached my end of the long bench where a hundred or more diners were enjoying lunch.

From behind his drooping brown mustache, he spoke to me in Spanish. I shook my head and told him, in Italian, that I didn’t understand. He switched to Italian. “You’re Gibernau.”

“I still don’t understand,” I said.

He put aside his cigarette (for the artwork in his establishment suggested Communist-Anarchist tendencies and the EU ban on tobacco in restaurants was being ignored) and reached out a finger. Poking me in the chest, he said: “You’re Gibernau.”

I shrugged, helplessly. “What does that mean?”

He mimed the act of revving up a motorcycle. “The rider, Gibernau.”

“Ah,” I said, miming the act of revving up a motorcycle and trying not to look fearful (which is how I feel when I even think of riding a motorcycle.)

“Yes.” He nodded, very happily.

“No,” I said, sadly, shaking my head. “Motorcyles are very dangerous. I don’t like them.”

The patron glanced over his shoulder. The cook was bouncing from foot to foot in excitement. The patron leaned in close enough that I could smell the smoke on his breath and see the broken veins around his baggy eyes. “Right now, you’re Gibernau.”

“Okay. It will be my pleasure.” (I’m even more polite in foreign languages than I am in English.)

He left the table and went behind the bar. I shrugged at my wife. “Is this a joke of some sort?” I asked her. “Does ‘Gibernau’ mean foreign asshole in Sicilian slang?”

I asked one of the youngsters across the table from us. “Yes,” one of them agreed. “It’s a joke.”

Before she could explain why it was funny, the clamor of loud Italian voices was silenced by the ringing sound of a spoon banging against a wine glass. The owner stood at the bar with the cook. A moment of silence, and he spoke:

“Today is a great day. Here, in our bar, we have il grande pilotti –– Gibernau.”

He lifted his hands in applause. The room joined him. The cook beamed.

I rose from the bench, raised my hand in modest acknowledgement, and resumed my seat.

The owner came over again. He brought an autograph book. The cook's, no doubt. “You’re Gibernau.” He was telling me this time, not asking me. I signed something that looked like a signature for someone whose name might’ve sounded like Gibernau.

“And Senora Gibernau, too,” he said.

My wife wrote: “Nothing’s finer than eating in your diner. Senora Gibernau.”

“A line from Seinfeld?” I said. “That’s how you’re signing for them.”

She laughed, as I imagine Senora Gibernau (who was a supermodel of some sort, it turns out) would have done.

On our return to our hotel, we searched the internet for “Gibernau” and came up with an extraordinarily famous Spanish rider who, at the time, was the only one who could challenge the great Italian Valentino Rossi. Extraordinarily famous among those who aren’t scared witless by bikes. He bore something of a resemblance to me, though I should add that I’m four inches taller and I don’t have titanium plates in my collar bones from falling off a Ducati at 200 miles per hour.

My wife and I became committed fans of Sete (Gibernau’s first name). We watched all his races from then on. Sadly he didn’t win any of them and retired a couple of years ago. So he reaped no benefit from my being mistaken for him.

Neither did I. When I eventually departed the restaurant to another round of applause, the owner insisted that I pay him the five Euros I owed for our spaghetti.

Published on March 29, 2012 04:25

•

Tags:

crime-fiction, memoir, motorbikes, sete-gibernau, sport

My Second Wife Predicts a Third

I write crime fiction. So here’s a mystery for you: Does anyone know an attractive young woman whose name is Wigoda? She might be my future third wife. That’s my second wife’s prediction, after all.

I write crime fiction. So here’s a mystery for you: Does anyone know an attractive young woman whose name is Wigoda? She might be my future third wife. That’s my second wife’s prediction, after all.Like many good mysteries, this one is historical. It’s also linked to the Holocaust.

Perhaps my mind turned to this subject because today is Holocaust Memorial Day in Israel, from whence I’m writing. This morning a siren will sound. Everyone will stop what they’re doing and stand in silence, whether driving or working (or, as once happened to me, weeping in a therapy session, when the therapist suddenly ignored my grief and got to her feet). When the siren sounds, I usually think: how the hell did a fellow from South Wales get here?

Of course, it was for love – of my first wife – that I came to Jerusalem. But how do I know my future wife’s name? And why do I wonder about that on such a nominally sad occasion?

The Holocaust museum and memorial in Jerusalem, Yad Vashem, constructed a new building a few years ago. The very first display is about a group of Lithuanian Jews who were killed by local Nazis early in the war. Murdered on the street. The display case includes some of their personal effects. The contents of each man’s wallet.

The first man’s identity card shows that his name was Shabtai Pruszan. Pruszan was the name of my first wife’s family before they got to Ellis Island. Not a common name. When I visited the museum the first time, I wondered at this coincidence.

My eyes drifted on to the next victim. His identity card listed him as Shabtai Blachor. More than a coincidence, I thought. That’s the family name of my second wife. Certainly not a common name, nor a common spelling. In fact there are less than a dozen of them in the whole U.S.

I told my wife about this when I got home from the museum. With a note of humor and a hint of suspicion, she asked: “What was the next victim’s name?”

Perhaps unconsciously I had noted that victim number three was named Wigoda. I mentioned this to my wife.

On the ground floor of our building, there’s a family named Wigoda. They have a married daughter. But you never know… She’s quite cute. My wife refers to her as my next wife.

“Wow,” said the present Mrs Rees. “For a guy from Wales, you’ve really entered the Jewish vortex when you’ve been married to the first two names to hit you in the face in Yad Vashem.”

So, gentle readers, I turn to you for a resolution to this mystery. My wife expects me to head down to the ground floor for my third wife. Or perhaps I’ll meet her when the Holocaust Memorial siren brings everyone to their feet today? Surely there’s some attractive Wigoda woman out there who’s prepared to wait it out until somehow I become available?

Suggestions please.

Published on April 18, 2012 22:58

•

Tags:

crime-fiction, holocaust, jerusalem, memoir

My Los Angeles

Eric, the scion of a soap fortune, pressed the "Wolf kills visitor" button inside the entrance of his Malibu beach-house. Outside his front door, I heard the approaching growls of an angry hound; a hatch opened and out sprang the three-foot neck of a blue-haired, red-eyed, mechanised wolf, drooling viciously over the welcome mat.

Eric, the scion of a soap fortune, pressed the "Wolf kills visitor" button inside the entrance of his Malibu beach-house. Outside his front door, I heard the approaching growls of an angry hound; a hatch opened and out sprang the three-foot neck of a blue-haired, red-eyed, mechanised wolf, drooling viciously over the welcome mat."That's cool," said Eric's friends. Eric smiled and led me inside to his pool, where, he said, there was a monster.

"It's down this end," he said. As I peered at the cartoon mermaids on the pool's floor, a Freddie Kruger model jumped up behind me and sprayed a jet of cold water down my back.

"I got you pretty good," Eric said, shaking my hand. A tanned girl in a bikini looked up from her deck chair and smiled, as if she'd seen this all before. I went out onto the veranda to watch Nicholas Cage playing in the sand with some children and a chubby blonde in shiny black-plastic trousers. The move star was without his toupee.

Los Angeles is full of the outrageously banal, the irresistibly empty, like Eric's $12 million home. Still, it's somehow one of America's most attractive cities, striving after substance in an instant kind of way, just as everyone here seems to feel they're only moments away from status and recognition in the entertainment business.

The city's most expensive shops, on Rodeo Drive and Via Rodeo, all decorate their windows with tastefully printed poetry by "y.o." -- none other than the artfully inane Yoko Ono. As Yoko orientalised about "following footprints in the sand / in the water," it seemed Los Angeles was the perfect place for her words. Only here could shopkeepers imagine a use for this most insubstantial of art, hyped and unread, as a way to make the act of consuming somehow more thoughtful, more deep. Just as most of Hollywood's movies are about dollar signs more than creativity. (At Universal Studios, tourists watch the less than terrifying spoutings of a mechanical shark and are told they've "survived Jaws, brought to you by Ocean Spray," a brand of cranberry juice.)

There's a conglomeration of ideologies in Los Angeles, as if it formulated its thoughts through the smog that hangs over the San Fernando valley, blurring the stripes of spinach-green foliage on the khaki hillsides. Like a radio that can switch bands instantly from AM talk shows to an FM rock station, Los Angeles is the ultimate American city, always seeking its next gig, hovering on the edge of the country. It threatens to break off in a techtonic cataclysm and fall into the Pacific, glimmering beneath the mountains along the coast road. The hip melange is there to greet you at LAX, the airport, where Hare Krishnas eschew their telltale robes and lure you into conversation with a high five from behind baseball caps and baggy homeboy jeans.

In a play I saw by one of Los Angeles' hottest new writers, Thomas M. Kostigen, a young man is described by his girlfriend: "He's thoughtful, but he's not thought-through." That's Los Angeles. And perhaps it took a Boston transplant like Kostigen to see it.

Los Angeles is no ardent, committed city of anger, like New York, with its downtown activists handing out needles to junkies, and arrogant Wall Streeters, crisp and one-dimensional in Ralph Lauren Polo shirts. It's no Frenchified town of think-tank pseudo-intellectuals like Washington D.C., and its snobbery can't compare to Boston's more desiccated variety.

In this city, they believe anything can be dressed up like a dream with a little cash, whether it's the backlot at Universal or a fat girl. An Argentinian who runs a West Hollywood salon selling extravagantly beaded wedding dresses for as much as $18,000 mimed the act of forcing fat into a

brace of petticoats and sneered at his customers. "They come in and think we can make them look like Cinderella. Well, for 90 percent of them, it just ain't gonna happen."

There's a danger in the dream, too, something of a nightmare quiet and smoothness, like riding in an air-conditioned Mercedes (leased not bought, of course, as most cars here are) through the shadows of the inner city. The riots of 1992 that wrecked South Central L.A. in the wake of the Rodney King trial showed how keyed the rest of America is to Los Angeles. The shock spread throughout the country. Even imperturbably ballsy New Yorkers called each other frantically with reports of shots fired at aeroplanes taking off from J.F.K. airport and massed blacks marching down from Harlem to pillage the Upper West Side.

That tension remains in Venice Beach, home to hippies and drug freaks, the place that spawned Jim Morrison. As tanned rollerbladers wind in their own Walkman-worlds down the path that twists along the beach, they're watched by crowds of blacks, milling about the cheap T-shirt stores and bargain shoe shops along the front.

A spray of cold water doused the back of my neck and I turned to see a seven-year-old black girl with a plastic cup in her hand run to her family, which giggled at her prank. I felt like a ringleted Jew strolling through the car-park outside a Nuremburg rally, waiting for the joking to turn harsher and, in the meanwhile, a game target.

A group of Black Hebrews stood in ranks between the rollerbladers and the crowded strip. A dozen black men in bright, satin turbans, they read from the Bible. One of them held a six-foot Star of David; another held a placard that listed the 12 tribes of Israel, redubbing them the 12 tribes of negroids. "Jesus was a black man," read one of their T-shirts.

Their leader, incongruously attired for the beach in the black, grey and white of arctic combat fatigues, held his microphone to the mouth of his acolyte reading a line from the Bible. Then he banged out his interpretation of the biblical verse with the venom of a rap song.

"That mean the white man and the white woman, the white race has done all that's evil; they are evil. He's oppressed and killed and raped and maimed. When the white man dropped the atomic bomb on the so-called Japanese at Hiroshima and Nagasaki, they shall reap that destruction, that's what that says there. That means all this, this crap -- " he waved an arm along the beach, left and right, taking in all of Los Angeles "-- is going to get wiped out. Read!"

The reader stumbled over the words "perpetual destruction." "Say what?" the leader said into his microphone. Then he gave up and pulled in the man with the Star of David to read instead.

With his clothing and imagery, the Israelite could have been a Christian, a Jew, a Muslim, a Sikh, or a corporal in the U.S Army -- just about anything except a so-called Japanese, in fact. Thought-through? Whatever, it looked good to him. He had to live in L.A., after all, until the crap was destroyed.

Yet the ideological confusion is one of Los Angeles' most engaging qualities for any visitor, because it's the muddleheadedness of those who are at least striving to figure it all out, to understand what they want. Like the bearded Harley Davidson rider rolling along La Cienega Boulevard, long hair flying from under his helmet. His bike bore the traditional Harley motto: "Live to ride." Below was a second slogan, of high-speed recovery: "Ride to live sober." Kick some of your dangerous habits -- just some of them.

I heard that same tone, confidently doubtful of its own effectiveness, in the voice of a man in the pool at the Jewish Community Center in West Hollywood. He couldn't stop talking about the muscle-relaxants he was taking for a firmer erection and the stool-softeners he hoped would cure his constipation. There's a solution for everything, but, if it doesn't work out, find a new guru, or a new pharmacist. Or a new producer.

A casting agent who works at MCA talked about the city's Museum of Tolerance, where displays on the Holocaust stand beside exhibits on racism in America's old south. "It makes you think," she breezed. "But that doesn't last."

In fact, Los Angeles' apparent vapidity brings with it an inverted snobbery of superficiality. Every time I suggested to Angelenos that their city is a pleasant place to be and, maybe, to live, they pounced on the chance to show how they'd seen through it all. "Oh, but it's really superficial," they'd say. And you'd have to be deep to see just how superficial everyone else is, wouldn't you. See what I mean?

Perhaps you can't think too much, when that might mean facing up to the idea that success isn't just round the corner. At a party thrown in a gigantic Italian restaurant by one of the city's biggest acting agencies, the Dolce & Gabana suits spoke of wealth. But few of those at the party were agents; most were struggling actors, trying to persuade those agents to take them on as clients, or they were clients eager for the agents to send them to better auditions.

"They're not actors," said my friend Avital, a successful stage and film actress with an Israeli Oscar under her belt who's trying to get ahead in Hollywood. "But they have to face so much rejection, they've got to really love something about what they do."

When I left the party, a slicked-down 26-year-old was trying to persuade the man with the guest list that he was supposed to have been invited. He was the same hopeful who'd been badgering the host when I arrived two hours before.

And rejection can come quickly, just like success. Jeffrey, a transplanted New Yorker with a trim grey beard and a collarless Armani shirt, told me about his plans for the modelling agency he founded 10 years ago. "I want to take over a bunch of small, Mom'n'Pop agencies," he said. I couldn't imagine Mom and Pop mixing with Hollywood's top models, and perhaps the people who now ran Jeffrey's agency couldn't either: three days later Jeffrey handed in his notice. When a friend learned Jeffrey had resigned from the agency, she said: "Again?"

Back at Eric's Malibu beach-house, I walked out along the private road and passed a minor film star I vaguely remembered from a role in some kind of comic vampire film. "Isn't that...uh?" I asked my friend.

"In this town, you see a lot of people who are someone, but you don't remember their names," my friend said. "In a while, no one else will, either."

Published on April 28, 2012 00:35

•

Tags:

california, crime-fiction, los-angeles, memoir, travel