Matt Rees's Blog - Posts Tagged "travel"

This is the life, Part 1: Germany

You’ll find a lot of writers’ blogs complaining about book tours. Not here. When I find one of my publishers around the world is happy to present me to hundreds of people who want to hear me talk about myself in fascinating places, I sign up right away.

That’s how I found myself in the Alte Pinakothek in Munich with very squeaky shoes.

More on that later…. I spent two weeks in March traveling Germany to promote the translation of my second Palestinian detective novel “A Grave in Gaza,” which is published there by C.H. Beck Verlag as “Ein Grab in Gaza”. It’s a family-owned publisher in business since the 1700s in Munich, run by a charming, shy man named Wolfgang Beck. In a world of megapublishers, there’s something wonderfully intimate about Beck’s office in the Schwabing district of Munich.

I began my tour at Lehmkuhl, a bookshop in Munich. The name means “Mudhole” in German and no one was able to offer an explanation for why anybody had chosen it. But there was a big crowd and a reading by myself and a local German actor. Unlike in other countries, where the audience gets fidgety the moment an author begins to read, Germans will happily listen to three chapters – including one read in English. It makes for long readings. Once you add in questions and banter and signing, they’re at least 90 minutes.

I had a day off in Munich after that and went to the Alte Pinakothek, where I disturbed the peace of the beautiful, airy galleries with a particularly squeaky pair of shoes. Entire school groups turned to see what the disturbance was… I wanted to see the famous self-portrait by Albrecht Duerer. In that portrait, the books all describe Duerer as gazing directly at the viewer, and that’s how it looks in photographs. Interestingly when you stand in front of the painting, it’s clear that he’s actually looking right through you, as though he were staring into some visionary future, focused absolutely on his art.

Or maybe he just couldn’t look me in the eye because of my squeaky shoes.

Thence to the enormous Leipzig Book Fair, held in a series of massive halls outside the historic town in eastern Germany. It’s lovely to see so many readers wandering the stalls, though anyone under the age of 26 appeared to be dressed as a Japanese cartoon character. My reading was hosted by Klaus Modick, a prominent German author who’s also my translator. At dinner in the old quarter of Leipzig in the Zum Arabischen Coffe Baum restaurant, Klaus and I had a long talk about the job of the translator. It was fascinating to hear the kinds of language choices a translator has to make. It’s notable, too, that even though I’ve been translated into 22 languages, Klaus is the only translator who sent me any questions about my original text. (My Danish translator, Jan Hansen, says that’s because I write such clear prose, there’s nothing to clarify. How do you say “You’re too kind” in Danish?)

Klaus also introduced me to “quark,” which is some kind of curd. It turns out Germans are obsessed with it the way Brits love Marmite.

Late that night there was a big publishers’ party in an old storage space beneath the medieval bastions of the city. The band: four German girls doing ABBA songs. Lots of happy German people. Very unhip, very nerdy. Really great!

Also at Leipzig I had coffee at the next table to Gunther Grass. He’s shorter than you’d expect…

How’s that for literary insight?

I went on to the Ruesselsheim area. South of Frankfurt, this is where Opel cars are manufactured – for the time being. Opel’s owned by GM and people are worried it’ll all be gone soon. In a town of 60,000, you can imagine what would happen if the 25,000 jobs at Opel disappeared.

The bookshop in Ruesselsheim is run by Hans-Juergen Jansen and his wife Monika, a charming pair who’ve created quite a cultural scene in this industrial town. So successful, in fact, that my first reading in the area inaugurated the opening of their new bookshop in nearby Gustavsburg. Imagine that: a new independent bookstore. There’s still hope for the world in these dark times, eh?

I also had an excellent pork dish at a restaurant overlooking the fast-flowing River Main in Ruesselsheim. They call the region “Rhine-Main” because of the confluence of the two great rivers. I dubbed the dish “Rhine-Main-Schwein,” and I think it might catch on….

I continued through Marburg, a historic university town on a mountain in the very center of Germany, where I spoke at the Roter Stern bookshop. (That means “Red Star,” and it started out as a communist collective in the 1960s. Nowadays, it’s still a collective, though no longer communist. At least I’m not naming names.)

The final pleasure of the trip was my stop at Schloss Elmau in the Bavarian Alps near Garmisch-Partenkirchen. It’s a gorgeous spa with a heated outdoor infinity pool on the roof. With my eyes on the snowy mountains all around, I swam a few laps with a big smile on my face.

A room at Elmau is 550 Euros a night. The delightful lady from Beck who accompanied me around Germany, Miriam Froitzheim, declared that she wanted to return to Elmau for her honeymoon. Men of Germany, Achtung!: you get an intelligent, beautiful wife AND a few nights at the most lovely hotel you’ll ever experience. Sounds like a deal. Macht schnell!

My reading at Elmau was organized by the wonderful Frau Ingeborg Praeger, who runs the extensive bookshop there. Frau Praeger spends about 40 days at Elmau in between her “outs” at her apartment in Munich. She helps put together the nightly cultural events at the spa – readings and musical performances mostly. When I was there Junot Diaz had just cancelled his appearance because he couldn’t be bothered to come from Cologne all the way up into the mountains to the spa. Which just shows you can win a Pulitzer and still not know which side your bread is buttered (as we say in Britain).

At Leipzig I had met Denis Scheck, a prominent literary critic on German tv and radio. He hosted my reading at Elmau and managed to ask questions no one else had asked, while also translating a summary of my answers into German without notes. At dinner, Herr Scheck proved himself to be quite the bon vivant. He’s writing a book about German wines. Did you know there’s no difference in taste between red and white wine? According to Denis, it’s all a matter of the serving temperature. Serve white wine at room temperature, it’ll taste like red wine. Chill red wine and you’ve got a white wine taste.

I’m teetotal. So it’s good to know that I’m only missing out on one taste experience.

This is the life, Part 2: Norway

It’s a glamorous life being an international author. For example, I got to go to Norway in the dead of winter when there was two feet of snow in the streets.

And I loved it.

You see, when your home is in the Middle East, experiencing some Arctic conditions are rather welcome. The Norwegians are a lovely people for whom books are a genuinely collective experience across society. And the reindeer meat is really good.

My second novel A Grave in Gaza appeared in Norwegian translation last month and my publisher Forlaget Press flew me to Oslo to do some interviews with local journalists. They timed the publication for a little before Easter, when all Norwegians traditionally buy a pile of crime novels and take them to their remote cabins in the forest for the holiday. Just to be sure that they’re isolated and feeling creeped out….

It’s my second publicity tour in Norway and I must say that the Israelis and Palestinians who reviled the Oslo Peace Process really blew it. Those Norwegians know what they’re about. Everything runs well. Everyone’s polite and interested. They laugh easily. They aren’t hypercritical.

It makes you wonder how they got involved with the prickly types who inhabit the Middle East in the first place.

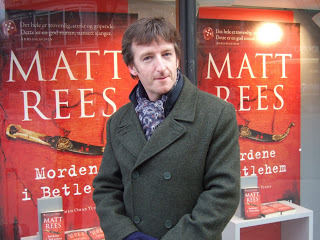

I met Thomas Mala, my exuberant main man at Press, at Oslo’s central station. He walked me along the relaxed pedestrian street leading past the Parliament and the National Theater up to the Royal Palace. At the bookshop on the corner opposite the theater, he showed me a little surprise: a window filled with my books and two enlarged copies of the cover. I’m not the most egotistical man in the world, but this felt good.

In the lovely Continental Hotel the next morning, I met up with Thor Arvid, a good-natured and quietly intellectual fellow from Press, who introduced me to the journalists I’d be meeting. Not that the first one needed introduction. Last year I’d met Fredrik Wandrup, culture correspondent at Dagbladet, the country’s main newspaper. A new father, he exuded contentment. The previous night he’d been to see Bob Dylan perform in Oslo. “It takes a while to figure out which song he’s playing,” Fredrik said. “But I liked it.”

Next up was a very sympathetic reporter from Klassekampen, which means “class struggle.” Its circulation is rising due to disgust with the bankers who flushed the world economy down the toilet. It also has a reputation for a hard line on the Palestinians. Still, even though my books don’t blame everything on the Israelis, Guri Kulaas understood my aim – to put a human face on the Palestinians, who’re so often seen only as stereotypes -- and she wrote a warm article.

Of course one of the pleasures of traveling to promote my books is meeting the people who publish them. Håkon Harket is the chief of Press in Oslo and a more cultured, thoughtful fellow I can’t imagine. He was generous enough to take me out to the Munch Museum in an Oslo suburb.

Munch is one of my favorite artists. Last year I visited the National Gallery in the center of Oslo, where some of his great works are kept, including Madonna (the most astonishing work of art) and The Scream. There’s more than one Scream, but the one at the National Gallery is better than the version at the Munch Museum.

Håkon walked me through an exhibit of Munch sketches for a series called Alfa and Omega. He was able to place these marvelous works of art in fascinating context from the Danish philosopher Kierkegaard through the plays of Henrik Ibsen.

Alfa and Omega, in Munch’s telling, seemed personifications of Adam and Eve, though somehow even more doomed. He drew the series with elements of expressionism and of the ancient Nordic myths.

He failed to mention brown cheese, however. As a Norwegian he really ought to have done. It’s almost as important to Norway as Odin and Freya and Thor ever were.

So when I was asked what I’d like in return for speaking at the Norwegian Publishers Association about my experience working with publishers around the world, naturally I said: brown cheese.

My speech went down well (although when I made a joke about wearing a Viking helmet with two horns, a gentleman in the audience protested that the real Vikings didn’t wear such helmets: “The Vikings weren’t horny,” he said.). They gave me a kilo of brown cheese, which looks and tastes like caramel chocolate, although its aftertaste is like a cheddar. They also gave me an existential novel by Dag Solstad, which I hadn’t asked for. (They’re publishers, after all.) I’m looking forward to reading it.

The speech was at the Litteraturhuset (Literature House), a central venue for book events and a gathering place for Norwegian publishers. Also home to the best reindeer meat, courtesy of chef Tore Namstad. It’s a very succulent meat with a liver aftertaste. If you’re shocked that I ate an innocent reindeer: next time I’m in Norway, I plan to eat whale.

I went out to Håkon’s place in a beautiful Oslo suburb called Jar for dinner on another night. The snow there was four feet deep, which made me feel that I’d got off lightly with the blizzard that had dumped itself on me downtown that morning. We ate with Håkon’s old friend Henning Kramer Dahl, a fascinating poet and translator who has introduced some major modern writers to Norwegian.

Along the edge of the Royal park from my hotel is the Ibsen Museum. The great playwright returned to Oslo for the last 11 years of his life. You can see the desk where he wrote every morning, which – for a writer and a lover of Ibsen’s plays like me, at least – has an almost mystical fascination.

Ibsen fact: he was five-feet-three. At the Museum you can see his extremely tall top hat and his high-heeled shoes. Clearly little Henrik had a complex. I took it as a reminder that a writer can have all the success in the world, but happiness has to do with accepting oneself.

Two other people I met in Norway about whom I’ll be writing more soon:

Scott Pack. The most innovative man in publishing? I think so. He’s the editor in chief of The Friday Project, part of Harper Collins. Among other ideas he’s been scanning the blogosphere for blogs to turn into books. With Tama Janowitz’s latest, he issued a limited signed printing of 1,000 copies, the buyers of which can send off for a free weird doll photo from Tama’s collection.

Monica Kristensen. After 30 years of polar exploration, she’s eaten polar bears and eaten her dog teams. She’s confronted a macho world. She’s earned a Ph.d in glaciology from Cambridge. Now she’s written a series of crime novels, though they're not yet in English (UK and US publishers, take heed). More on her to come.

The Best Bookshop in Germany

In the town of Ruesselsheim, near Mainz, I've discovered the best bookshop in Germany. The Buecherhaus Jansen stands in a down-at-heel pedestrian street at the heart of an industrial town (home to Opel cars, a troubled subsidiary of General Motors), surrounded mostly by doner kebab restaurants and discount stores. Hans-Juergen Jansen has built his store into a cultural center for the surrounding towns. He has a busy program of visiting authors, mostly German, and other performers for children, on whom his bookshop has a particular focus. His wife Monika also does seminars about books and performance, and his daughter puts on shows for kids (she travels the country with her Slovakian partner performing an adaptation of The Gruffalo.) I've done three readings for Herr Jansen and each time they're full, because of his efficient publicity operation and because customers know that he brings them something they can't get elsewhere in their area. On my recent visit (photo) Herr Jansen and his assistant Sonja had put up a window display about my book A Grave in Gaza which featured smashed cinder blocks a la Gaza. But inside the bookshop everything is orderly and filled with the welcoming scent of new books. Ruesselsheim isn't the most glamorous spot in Germany, but I can't wait to visit again.

Scared away

Here's my latest post on the International Crime Authors Reality Check blog:

I keep finding new reasons why I write my novels about the Palestinians. Usually these reasons have nothing to do with the Palestinians.

Here’s the one that may be the deepest, the one I’ve known about for a while, but have only recently been able to face up to: it’s because I’m scared of home.

Not so long ago, I read the 1992 novel “Fat Lad” by Northern Irish novelist Glenn Patterson. It’s a terrific book, examining Belfast’s changing political landscape through the story of a young man returning after a decade in England.

But I was struck by my reaction to the nostalgic tone of the main character’s memories. They filled me with terror and loathing.

What were these memories? Patterson recalls Choppers, which were long-handled bikes for kids. I never had one. The main character lays out his desk with a bottle of Quink, a brand name for ink which I used at school. I wasn’t happy at school. He listens to Frankie Goes to Hollywood, a specific remix of the song Relax. Relax was number one in the charts when I was in high school; I chose to listen to music that no one else liked in high school, because I didn’t like anyone and imagined no one would like me.

I cite other examples of Patterson’s nostalgia, but I think perhaps you get the picture.

Patterson created a world coterminous with my own childhood in Wales. For Patterson, who went to England for graduate work and returned to his hometown, nostalgia is filled with warmth and friendship, even amid the violence of Belfast. Nostalgia doesn’t work if the period being viewed through rose-colored spectacles was experienced through isolation and self-loathing. I left home, and I’ve never been back.

I used to think: Never mind, everyone’s pretty miserable as a teenager. In a series of interviews with other writers on my blog, I started asking: “Do you have a pain from childhood that drives you to write?” Almost all of them responded that, No, they had pretty good childhoods. At first I refused to believe it. (I even told Miriam Froitzheim, the delightful German who gave me my copy of “Fat Lad,” that she couldn’t be a writer because she’d had a happy childhood and was a very well-balanced, happy adult. Well, I take it back, Miriam. It’s just me.)

I started to realize I had been pretty miserable in my twenties and early thirties, too. It wasn’t only my childhood. I left Britain and went to America. But I boozed myself into a different kind of isolation there, before I found my way to the Middle East.

During those early times I wrote stories of alienation – loners driven to acts of violence or victims of violence, troubled men stuck in unfulfilling relationships with doomed women. With the Palestinians, I came out of that darkness. It wasn’t just the exotic magic of their culture, their architecture, their cuisine. It was that their memories weren’t mine.

No Palestinian has ever said: Did you have a Chopper when you were a kid? Remember having those Quink-stains on your fingers at school? Did you grope your first girl dancing to Frankie at the school disco?

I’ve never had to say to a Palestinian: No, I was a miserable kid and I hate you for having been happy.

This freed me from the angst trap. Me, and my writing, both. I could enter the heads of characters who had been scarred – I understood what it was to have suffered. But they’d been scarred by war and occupation. That allowed me to see my own sufferings for what they were: bad, but things that could be overcome by personal development.

If you’re a Palestinian, you can go to therapy and meditate and listen to Mozart all you want. You’ll be better off, but you’ll still be living under occupation. In my case, life among a people with real problems helped me separate from the anger that clung to me all those years. Beside them, my life was a constant beach holiday. In Jerusalem I go for days on end without meeting anyone as relaxed as me. I’ve started to think perhaps this is the real me.

I’ve lived in the Middle East 13 years now. Last month it was 20 years since I left Britain (when I was 22.) Soon all the nostalgia novels will be about periods of British life of which I know nothing, because I was no longer living there. In the Middle East, I’ve been insulated, distant from British culture and not really immersed in Palestinian or Israeli pop culture. Free from all the babble, from the reminiscences of others’ lives which are supposed to be my shared experiences.

Free not to be a member of a broader society. Free to live inside my head. Which is good. Because that’s where novels are written.

I keep finding new reasons why I write my novels about the Palestinians. Usually these reasons have nothing to do with the Palestinians.

Here’s the one that may be the deepest, the one I’ve known about for a while, but have only recently been able to face up to: it’s because I’m scared of home.

Not so long ago, I read the 1992 novel “Fat Lad” by Northern Irish novelist Glenn Patterson. It’s a terrific book, examining Belfast’s changing political landscape through the story of a young man returning after a decade in England.

But I was struck by my reaction to the nostalgic tone of the main character’s memories. They filled me with terror and loathing.

What were these memories? Patterson recalls Choppers, which were long-handled bikes for kids. I never had one. The main character lays out his desk with a bottle of Quink, a brand name for ink which I used at school. I wasn’t happy at school. He listens to Frankie Goes to Hollywood, a specific remix of the song Relax. Relax was number one in the charts when I was in high school; I chose to listen to music that no one else liked in high school, because I didn’t like anyone and imagined no one would like me.

I cite other examples of Patterson’s nostalgia, but I think perhaps you get the picture.

Patterson created a world coterminous with my own childhood in Wales. For Patterson, who went to England for graduate work and returned to his hometown, nostalgia is filled with warmth and friendship, even amid the violence of Belfast. Nostalgia doesn’t work if the period being viewed through rose-colored spectacles was experienced through isolation and self-loathing. I left home, and I’ve never been back.

I used to think: Never mind, everyone’s pretty miserable as a teenager. In a series of interviews with other writers on my blog, I started asking: “Do you have a pain from childhood that drives you to write?” Almost all of them responded that, No, they had pretty good childhoods. At first I refused to believe it. (I even told Miriam Froitzheim, the delightful German who gave me my copy of “Fat Lad,” that she couldn’t be a writer because she’d had a happy childhood and was a very well-balanced, happy adult. Well, I take it back, Miriam. It’s just me.)

I started to realize I had been pretty miserable in my twenties and early thirties, too. It wasn’t only my childhood. I left Britain and went to America. But I boozed myself into a different kind of isolation there, before I found my way to the Middle East.

During those early times I wrote stories of alienation – loners driven to acts of violence or victims of violence, troubled men stuck in unfulfilling relationships with doomed women. With the Palestinians, I came out of that darkness. It wasn’t just the exotic magic of their culture, their architecture, their cuisine. It was that their memories weren’t mine.

No Palestinian has ever said: Did you have a Chopper when you were a kid? Remember having those Quink-stains on your fingers at school? Did you grope your first girl dancing to Frankie at the school disco?

I’ve never had to say to a Palestinian: No, I was a miserable kid and I hate you for having been happy.

This freed me from the angst trap. Me, and my writing, both. I could enter the heads of characters who had been scarred – I understood what it was to have suffered. But they’d been scarred by war and occupation. That allowed me to see my own sufferings for what they were: bad, but things that could be overcome by personal development.

If you’re a Palestinian, you can go to therapy and meditate and listen to Mozart all you want. You’ll be better off, but you’ll still be living under occupation. In my case, life among a people with real problems helped me separate from the anger that clung to me all those years. Beside them, my life was a constant beach holiday. In Jerusalem I go for days on end without meeting anyone as relaxed as me. I’ve started to think perhaps this is the real me.

I’ve lived in the Middle East 13 years now. Last month it was 20 years since I left Britain (when I was 22.) Soon all the nostalgia novels will be about periods of British life of which I know nothing, because I was no longer living there. In the Middle East, I’ve been insulated, distant from British culture and not really immersed in Palestinian or Israeli pop culture. Free from all the babble, from the reminiscences of others’ lives which are supposed to be my shared experiences.

Free not to be a member of a broader society. Free to live inside my head. Which is good. Because that’s where novels are written.

Neon pee on the Reeperbahn, and other travels

The whole point of travel is to see Red Light districts around the world. That’s what I assume my German publisher C.H. Beck thinks. Or maybe that's what they think I'll like. Anyway, they keep sending me to Hamburg, which has one of the most famous naughty neighborhoods in the world.

At the invitation of the extremely professional Harbour Front Literaturfestival and in the company of my Beck “handler,” I made another visit to Hamburg last month. I really like the place tremendously. Not because of the Reeperbahn, the red light strip, but because the city faces the wide River Elbe in every sense, it’s affordable, and its people are liberal and open.

That’s a very pleasant change for me, given that I live in the Middle East, a region where there’s no water, things are quite expensive, and the people… Well, I think you’ve read about them.

I wandered the Reeperbahn with Miriam Froitzheim, the wonderful Beck lady whose job is to get me on the right trains, feed me, and pretend that it isn’t boring for her to listen to my same shtick every night at my readings. We particularly enjoyed the public toilet on the center-island of the road, which was decorated with two little neon boys peeing pink neon streams of urine at each other.

Other than that, it must be said that red light districts put me in mind less of sex than they do of sexually transmitted disease. Not to mention theft and violence. I gave some money to a beggar because it seemed better than putting it in the slot of a peep-show and headed for the river.

I stayed a couple of nights on the Cap San Diego, a 1920s ocean liner which is now a floating hotel in the heart of Hamburg’s docks (It goes downriver to the sea twice a year). It’s only 80 Euros a night, which makes it pretty cheap for a hotel anywhere in Europe. Its comfortable wooden interiors look out onto the cranes of the dockyard across the rolling Elbe.

You can see the yacht Roman Abramovic (Russian oligarch owner of a boring English soccer club) is building at 1 million Euros a meter, which is less than what he pays for soccer players but still quite expensive. It’ll be 150 meters long when it's finished early in the winter. Along the river is a new Philharmonic building, which probably cost less than the yacht and isn’t crass or disgusting.

From my porthole, I also watched boats ferrying people to the theater on the other side of the river. Now showing, “The Lion King”: a nine-year run, booked six months ahead. Another boat went by advertising “Tarzan,” a musical with songs by Phil Collins which was cast on a German tv reality show.

I commented to Miriam that I’m insulated from such pop-cultural crap. By living in Jerusalem, a city where nothing ever happens. Except terrorism.

She used the opportunity to introduce me to a very useful German expression: “Was bringt dich auf die Palme?” Literally, what sends you up a palm tree? (ie. What drives you nuts?) Answer: Phil Collins musicals, of course.

En route to Hamburg, my train stopped in Hannover. Throughout the intifada, I drove a Mercedes armored car through the West Bank. It had Hannover plates (I’d imported it from Germany). I gave a quiet thanks to the town which had stopped a few bullets for me.

Then it was off to Aachen, near the Dutch border, where my reading was in Charlemagne’s 1200-year-old hunting lodge, the Frankenbergerhof. Charlemagne is the main man in Aachen. His throne sits in the town’s cathedral, which is a beautiful hodge-podge that looks enormous on the outside and is quite small on the inside. Unless the Aachners were hiding some part of it from me.

They also have the Devil’s thumbprint on the door of the cathedral. That happened when Lucifer got his finger caught in the door. The Devil being that stupid, you see.

Opposite the lovely Aachen town hall, I sat for lunch at the Brauerei Goldener Schwan. While some may travel for red light districts, I go for the food. I ate Aachner puttes, also known as Himmel und Erd (Heaven and Earth): blood sausage of a very soft consistency, fried onions, fried apples, and mashed potatos. More Himmel than Erd, I’d say.

I worked off the “puttes” by wandering Aachen with Miriam, a native of the town. Actually I didn’t really walk off the lunch. As we strolled, we bought a packet of Aachner Printen, the clovey gingerbread-like cookies for which the town is famed (not really gingerbread, which is sweetened with honey; these are sweetened with sugar). So on balance I probably got fatter in Aachen.

But at least no one peed neon at me.

Next post: I finish my German-language reading tour in Switzerland and actually take a vacation for the first time in two years, bumping into someone who used to play football for Roman Abramovic… Next post after that: I field emails from people telling me that reading tours sound much like vacations, so I oughtn’t to complain that it’s been two years since I had a formal break….

At the invitation of the extremely professional Harbour Front Literaturfestival and in the company of my Beck “handler,” I made another visit to Hamburg last month. I really like the place tremendously. Not because of the Reeperbahn, the red light strip, but because the city faces the wide River Elbe in every sense, it’s affordable, and its people are liberal and open.

That’s a very pleasant change for me, given that I live in the Middle East, a region where there’s no water, things are quite expensive, and the people… Well, I think you’ve read about them.

I wandered the Reeperbahn with Miriam Froitzheim, the wonderful Beck lady whose job is to get me on the right trains, feed me, and pretend that it isn’t boring for her to listen to my same shtick every night at my readings. We particularly enjoyed the public toilet on the center-island of the road, which was decorated with two little neon boys peeing pink neon streams of urine at each other.

Other than that, it must be said that red light districts put me in mind less of sex than they do of sexually transmitted disease. Not to mention theft and violence. I gave some money to a beggar because it seemed better than putting it in the slot of a peep-show and headed for the river.

I stayed a couple of nights on the Cap San Diego, a 1920s ocean liner which is now a floating hotel in the heart of Hamburg’s docks (It goes downriver to the sea twice a year). It’s only 80 Euros a night, which makes it pretty cheap for a hotel anywhere in Europe. Its comfortable wooden interiors look out onto the cranes of the dockyard across the rolling Elbe.

You can see the yacht Roman Abramovic (Russian oligarch owner of a boring English soccer club) is building at 1 million Euros a meter, which is less than what he pays for soccer players but still quite expensive. It’ll be 150 meters long when it's finished early in the winter. Along the river is a new Philharmonic building, which probably cost less than the yacht and isn’t crass or disgusting.

From my porthole, I also watched boats ferrying people to the theater on the other side of the river. Now showing, “The Lion King”: a nine-year run, booked six months ahead. Another boat went by advertising “Tarzan,” a musical with songs by Phil Collins which was cast on a German tv reality show.

I commented to Miriam that I’m insulated from such pop-cultural crap. By living in Jerusalem, a city where nothing ever happens. Except terrorism.

She used the opportunity to introduce me to a very useful German expression: “Was bringt dich auf die Palme?” Literally, what sends you up a palm tree? (ie. What drives you nuts?) Answer: Phil Collins musicals, of course.

En route to Hamburg, my train stopped in Hannover. Throughout the intifada, I drove a Mercedes armored car through the West Bank. It had Hannover plates (I’d imported it from Germany). I gave a quiet thanks to the town which had stopped a few bullets for me.

Then it was off to Aachen, near the Dutch border, where my reading was in Charlemagne’s 1200-year-old hunting lodge, the Frankenbergerhof. Charlemagne is the main man in Aachen. His throne sits in the town’s cathedral, which is a beautiful hodge-podge that looks enormous on the outside and is quite small on the inside. Unless the Aachners were hiding some part of it from me.

They also have the Devil’s thumbprint on the door of the cathedral. That happened when Lucifer got his finger caught in the door. The Devil being that stupid, you see.

Opposite the lovely Aachen town hall, I sat for lunch at the Brauerei Goldener Schwan. While some may travel for red light districts, I go for the food. I ate Aachner puttes, also known as Himmel und Erd (Heaven and Earth): blood sausage of a very soft consistency, fried onions, fried apples, and mashed potatos. More Himmel than Erd, I’d say.

I worked off the “puttes” by wandering Aachen with Miriam, a native of the town. Actually I didn’t really walk off the lunch. As we strolled, we bought a packet of Aachner Printen, the clovey gingerbread-like cookies for which the town is famed (not really gingerbread, which is sweetened with honey; these are sweetened with sugar). So on balance I probably got fatter in Aachen.

But at least no one peed neon at me.

Next post: I finish my German-language reading tour in Switzerland and actually take a vacation for the first time in two years, bumping into someone who used to play football for Roman Abramovic… Next post after that: I field emails from people telling me that reading tours sound much like vacations, so I oughtn’t to complain that it’s been two years since I had a formal break….

Those disorganized Swiss

You know the reputation. "Swiss" isn't a nationality. It's really an adjective meaning highly organized and perhaps even a little too punctilious.

That's a myth. The place is just like the Middle East... (Look, I write fiction, but I may be onto something. Read on.)

On my recent reading tour, I stopped in Basel as a guest of the superb Literaturhaus Basel. Everyone told me to go the city's main art museum for an exhibition of Van Gogh landscapes. After a stroll over the Rhine and up into Basel's beautiful Baroque district, I stumbled on a scene reminiscent of a UN food station in Gaza.

Ok, not quite. That's the fiction writer meeting the sensationalist journalist, perhaps. But still it wasn't Swiss.

There were two lines. One was vaguely marked as being for the Van Gogh exhibit. The other, for the rest of the collection. I decided the extreme length of the Van Gogh line was enough to put me off. I joined the other line, which turned out to move very slowly.

A pair of Italian-speaking Swiss ladies tried to jump under the rope to skip ahead in the van Gogh line. A guard told them this wasn't fair and sent them back. But a few minutes later I saw they were back in position, keeping a low profile.

When I got to the front of my line, I discovered that I could buy a ticket for Van Gogh there too.

It left me wondering what's happened to the Swiss (sort of.) If I hadn't lived in the Middle East and encountered far more un-line-like lines, I might've really blown a fuse. Maybe I've just calmed down enough in my life that now I'm a little bit Swiss myself, trusting that if someone else pushes in it's their problem and I oughtn't to worry about it.

I roamed the wonderful museum and returned to my hotel the Krafft Basel. I settled into a chair overlooking the Rhine and asked for a coffee. It seemed I was too late for the lunchroom. I was directed to the smoking room at the front of the hotel.

Now I'd already ventured into that very attractive room. Only to be repelled by the stench of cigars. It smelled like my great-uncle's dungarees after he'd drunk a bottle of Johnny Walker and peed himself. (Switzerland's probably the only place in Western Europe these days where you can settle down to make a public area of a hotel smell like a nasty urinal. God bless the EU.)

With a Middle Eastern refusal to accept rules, I told the waitress she could serve me where I was and I'd leave before the remaining diners were done. She agreed. So maybe it's my fault the Swiss allow rules to be bent.

I set out that evening to corrupt more upstanding Swiss. I enjoyed my reading at the Literaturhaus, which was organized by Katrin Eckert there. (She took me over the Rhine in an old wooden ferry that's powered by nothing more than the current of the river. One of the most peaceful experiences I think it's possible to have in a big city.) She brought in Rafael Newman, a translator and all-around intelligent fellow, to interview me and translate.

I'm used to more or less the same kinds of questions at my readings (for which I bear no grudge, they being the most apposite things that come to mind on reading my books). But when Rafael asked me about my literary influences, he had something different in mind: "I'm thinking of the sandstorm in A GRAVE IN GAZA, which is really blinding, and Huxley, Eyeless in Gaza, back through Milton and Samson Agnonistes, going right back to Greek tragedy, where one of the great tragedies ends with a storm."

"I'm glad you asked me that," I said, pondering how to adapt my usual answer about the influence of Raymond Chandler on my books. "Mainly I go back to the Bible..."

The ability to bullshit on my feet is one of the few things I gained from three yeas at Oxford University. Anyway, I told you I was corrupting the Swiss...

Next it was on to a family vacation with my wife, son, and babysitter on Lake Geneva. We stayed in a small village on the slopes of the Jura, smelling the cooking-pie scent of the ripe grapes on the vines. In Nyon, a stinking rich little place on the lake if ever I saw one, I was happily fellating a $5 single-scoop chocolate ice-cream when Graeme Le Saux, formerly an England soccer played, walked by with his black labrador.

During his career, Le Saux was sometimes taunted by other players for being less manly (read, less ill-educated) than they. One Liverpool player, Robbie Fowler, famously pointed his backside at Le Saux and made a comment about what he imagined Le Saux might like to do to it. Well, now who's taunting who. Fowler presumably lives in crime-ridden Liverpool, waking every morning to wonder if his hubcaps are still on his car. Old Graeme lives on Lake Geneva.

I, too, sometimes wonder if I could've lived my life in a more pleasurable place than the Middle East, where I've been for 13 years now. But as I licked my Black Forest ice-cream, I looked out over the blue lake and thought that I wasn't doing so badly as lifestyles go. And the hubcaps on my wife's car were stolen long ago.

That's a myth. The place is just like the Middle East... (Look, I write fiction, but I may be onto something. Read on.)

On my recent reading tour, I stopped in Basel as a guest of the superb Literaturhaus Basel. Everyone told me to go the city's main art museum for an exhibition of Van Gogh landscapes. After a stroll over the Rhine and up into Basel's beautiful Baroque district, I stumbled on a scene reminiscent of a UN food station in Gaza.

Ok, not quite. That's the fiction writer meeting the sensationalist journalist, perhaps. But still it wasn't Swiss.

There were two lines. One was vaguely marked as being for the Van Gogh exhibit. The other, for the rest of the collection. I decided the extreme length of the Van Gogh line was enough to put me off. I joined the other line, which turned out to move very slowly.

A pair of Italian-speaking Swiss ladies tried to jump under the rope to skip ahead in the van Gogh line. A guard told them this wasn't fair and sent them back. But a few minutes later I saw they were back in position, keeping a low profile.

When I got to the front of my line, I discovered that I could buy a ticket for Van Gogh there too.

It left me wondering what's happened to the Swiss (sort of.) If I hadn't lived in the Middle East and encountered far more un-line-like lines, I might've really blown a fuse. Maybe I've just calmed down enough in my life that now I'm a little bit Swiss myself, trusting that if someone else pushes in it's their problem and I oughtn't to worry about it.

I roamed the wonderful museum and returned to my hotel the Krafft Basel. I settled into a chair overlooking the Rhine and asked for a coffee. It seemed I was too late for the lunchroom. I was directed to the smoking room at the front of the hotel.

Now I'd already ventured into that very attractive room. Only to be repelled by the stench of cigars. It smelled like my great-uncle's dungarees after he'd drunk a bottle of Johnny Walker and peed himself. (Switzerland's probably the only place in Western Europe these days where you can settle down to make a public area of a hotel smell like a nasty urinal. God bless the EU.)

With a Middle Eastern refusal to accept rules, I told the waitress she could serve me where I was and I'd leave before the remaining diners were done. She agreed. So maybe it's my fault the Swiss allow rules to be bent.

I set out that evening to corrupt more upstanding Swiss. I enjoyed my reading at the Literaturhaus, which was organized by Katrin Eckert there. (She took me over the Rhine in an old wooden ferry that's powered by nothing more than the current of the river. One of the most peaceful experiences I think it's possible to have in a big city.) She brought in Rafael Newman, a translator and all-around intelligent fellow, to interview me and translate.

I'm used to more or less the same kinds of questions at my readings (for which I bear no grudge, they being the most apposite things that come to mind on reading my books). But when Rafael asked me about my literary influences, he had something different in mind: "I'm thinking of the sandstorm in A GRAVE IN GAZA, which is really blinding, and Huxley, Eyeless in Gaza, back through Milton and Samson Agnonistes, going right back to Greek tragedy, where one of the great tragedies ends with a storm."

"I'm glad you asked me that," I said, pondering how to adapt my usual answer about the influence of Raymond Chandler on my books. "Mainly I go back to the Bible..."

The ability to bullshit on my feet is one of the few things I gained from three yeas at Oxford University. Anyway, I told you I was corrupting the Swiss...

Next it was on to a family vacation with my wife, son, and babysitter on Lake Geneva. We stayed in a small village on the slopes of the Jura, smelling the cooking-pie scent of the ripe grapes on the vines. In Nyon, a stinking rich little place on the lake if ever I saw one, I was happily fellating a $5 single-scoop chocolate ice-cream when Graeme Le Saux, formerly an England soccer played, walked by with his black labrador.

During his career, Le Saux was sometimes taunted by other players for being less manly (read, less ill-educated) than they. One Liverpool player, Robbie Fowler, famously pointed his backside at Le Saux and made a comment about what he imagined Le Saux might like to do to it. Well, now who's taunting who. Fowler presumably lives in crime-ridden Liverpool, waking every morning to wonder if his hubcaps are still on his car. Old Graeme lives on Lake Geneva.

I, too, sometimes wonder if I could've lived my life in a more pleasurable place than the Middle East, where I've been for 13 years now. But as I licked my Black Forest ice-cream, I looked out over the blue lake and thought that I wasn't doing so badly as lifestyles go. And the hubcaps on my wife's car were stolen long ago.

Researching the novel

Novelists aren’t journalists. Research for a novel isn’t the same as researching a journalistic article.

I’d have thought that was too obvious to need stating. But then I became a published novelist, and I realized that people thought the two things were rather the same.

I was a journalist for almost 20 years before my first novel was published. THE COLLABORATOR OF BETHLEHEM is a crime novel set in Bethlehem during the intifada, and I’d spent over a decade covering the Palestinians by the time the book came out in 2007. No need for new research there.

Much of the next two books, A GRAVE IN GAZA and THE SAMARITAN’S SECRET, were based on stories I had covered as a journalist. Though I returned to the places many times before I wrote the books, these visits were mainly to record details of place, smell and weather. It wasn’t to interview people, as a journalist must.

That’s because I wanted the books to have their basis less in the political moment at which I had covered those stories, and more in the emotional response I had observed in other people and in myself as those events unfolded.

Things were different when I came to research my new novel, THE FOURTH ASSASSIN, which will be published in February.

THE FOURTH ASSASSIN is set in Brooklyn, New York, where there’s a growing community of Palestinian immigrants. I lived in New York in the 1990s, when I covered Wall Street for some US newspapers and magazines. I was a Greenwich Village type, with forays to Soho, Tribeca and the Lower East Side. I used to go months without leaving Manhattan. Brooklyn wasn’t exactly one of my regular haunts. So last year I went out to Bay Ridge, where most Palestinians live, and met a couple of people. I toured the neighborhood with a kid in his late teens and learned about the gang culture.

I specifically didn’t want to do what a journalist does. I didn’t want to sit down and pull out my notepad, though I can see why novelists may feel the urge to do so. I wanted to walk the streets as my detective Omar Yussef would – a little alienated, not knowing quite where I was, out of place. I know Omar Yussef – the real man and his fictional manifestation – well enough to make my way through Bay Ridge as though he were with me.

During my visit to New York, I stopped in at the home of some friends who had been correspondents for a US newspaper in Jerusalem. One of them said: “So who’re you talking to in Brooklyn?”

It was a journalist’s question—who you’re talking to will determine the depth of information you garner and therefore will signal the worth of your article. I felt a stab of defensiveness. It was as though she had accused me of not doing my job. Of course, I wasn’t doing my job, because I no longer had a job. Journalism was my job. Now I’m a novelist. Most definitely not a job.

But the twinge I felt at her query alerted me to the difference in my new “métier” (let’s see how many ways I can find to avoid referring to my writing as a “job”).

I recently finished writing the manuscript of a novel about Mozart. When I began it, various friends suggested I talk to “experts” on the subject. I didn’t. Because they weren’t experts on what I was writing about. They were experts on the known facts about Mozart. Well, I can read as well as they can.

What I needed were musicians, who could tell me how they get inside a Mozart piece, how they plot out their performance emotionally. I needed friends in Vienna who could take me to little-known places that would give me the atmosphere of the eighteenth century in that city. I needed to learn to play the piano, to feel the extent of Mozart’s genius and to be moved with (rather than just “by”) his music.

A journalist collates the impressions and assertions of others. As a novelist, I’m focused on my own impressions. If there’s anything to be asserted in my books, it ought not to be a digest of someone else’s thoughts.

I’m starting this process again. The novel I’m researching now will be set in Italy in 1600 and will be about an artist. I’m off to Rome in a few weeks, and already friends are asking me which experts I’m intending to interview. I may talk to some art historians, but they won’t be the most important factor in my research. That’ll come when I put some oil on canvas.

I don’t expect to show anyone the results of my daubings (just as I don’t want anyone except my two-year-old son to listen to my rotten piano playing). But the sensation of working with paint is going to be much more important than hearing someone’s assessment of how it was for someone else long dead to muck about with oils.

(I posted this earlier today on the International Crime Authors Reality Check blog, which I write along with Christopher G. Moore, Barbara Nadel and Colin Cotterill. Check it out.)

I’d have thought that was too obvious to need stating. But then I became a published novelist, and I realized that people thought the two things were rather the same.

I was a journalist for almost 20 years before my first novel was published. THE COLLABORATOR OF BETHLEHEM is a crime novel set in Bethlehem during the intifada, and I’d spent over a decade covering the Palestinians by the time the book came out in 2007. No need for new research there.

Much of the next two books, A GRAVE IN GAZA and THE SAMARITAN’S SECRET, were based on stories I had covered as a journalist. Though I returned to the places many times before I wrote the books, these visits were mainly to record details of place, smell and weather. It wasn’t to interview people, as a journalist must.

That’s because I wanted the books to have their basis less in the political moment at which I had covered those stories, and more in the emotional response I had observed in other people and in myself as those events unfolded.

Things were different when I came to research my new novel, THE FOURTH ASSASSIN, which will be published in February.

THE FOURTH ASSASSIN is set in Brooklyn, New York, where there’s a growing community of Palestinian immigrants. I lived in New York in the 1990s, when I covered Wall Street for some US newspapers and magazines. I was a Greenwich Village type, with forays to Soho, Tribeca and the Lower East Side. I used to go months without leaving Manhattan. Brooklyn wasn’t exactly one of my regular haunts. So last year I went out to Bay Ridge, where most Palestinians live, and met a couple of people. I toured the neighborhood with a kid in his late teens and learned about the gang culture.

I specifically didn’t want to do what a journalist does. I didn’t want to sit down and pull out my notepad, though I can see why novelists may feel the urge to do so. I wanted to walk the streets as my detective Omar Yussef would – a little alienated, not knowing quite where I was, out of place. I know Omar Yussef – the real man and his fictional manifestation – well enough to make my way through Bay Ridge as though he were with me.

During my visit to New York, I stopped in at the home of some friends who had been correspondents for a US newspaper in Jerusalem. One of them said: “So who’re you talking to in Brooklyn?”

It was a journalist’s question—who you’re talking to will determine the depth of information you garner and therefore will signal the worth of your article. I felt a stab of defensiveness. It was as though she had accused me of not doing my job. Of course, I wasn’t doing my job, because I no longer had a job. Journalism was my job. Now I’m a novelist. Most definitely not a job.

But the twinge I felt at her query alerted me to the difference in my new “métier” (let’s see how many ways I can find to avoid referring to my writing as a “job”).

I recently finished writing the manuscript of a novel about Mozart. When I began it, various friends suggested I talk to “experts” on the subject. I didn’t. Because they weren’t experts on what I was writing about. They were experts on the known facts about Mozart. Well, I can read as well as they can.

What I needed were musicians, who could tell me how they get inside a Mozart piece, how they plot out their performance emotionally. I needed friends in Vienna who could take me to little-known places that would give me the atmosphere of the eighteenth century in that city. I needed to learn to play the piano, to feel the extent of Mozart’s genius and to be moved with (rather than just “by”) his music.

A journalist collates the impressions and assertions of others. As a novelist, I’m focused on my own impressions. If there’s anything to be asserted in my books, it ought not to be a digest of someone else’s thoughts.

I’m starting this process again. The novel I’m researching now will be set in Italy in 1600 and will be about an artist. I’m off to Rome in a few weeks, and already friends are asking me which experts I’m intending to interview. I may talk to some art historians, but they won’t be the most important factor in my research. That’ll come when I put some oil on canvas.

I don’t expect to show anyone the results of my daubings (just as I don’t want anyone except my two-year-old son to listen to my rotten piano playing). But the sensation of working with paint is going to be much more important than hearing someone’s assessment of how it was for someone else long dead to muck about with oils.

(I posted this earlier today on the International Crime Authors Reality Check blog, which I write along with Christopher G. Moore, Barbara Nadel and Colin Cotterill. Check it out.)

Book Tours Not Just Ego Tripping

Not long ago a friend of mine commented that my travels to promote my books must be a great pleasure to me. “You just have to talk about yourself,” he sneered. “You must like that.”

Not long ago a friend of mine commented that my travels to promote my books must be a great pleasure to me. “You just have to talk about yourself,” he sneered. “You must like that.”I ignored the implied insult (until now). But it struck me that people might think book tours are literally ego-trips. Wrong on two counts.

First, it’s only on book tour that people will frequently come up to you and say that you look better in your jacket photo. In Aachen last year, a bookseller pointed at my photo and said, “This handsome man is not you.” In Hamburg, a woman said: “The photo was taken many years ago, no?” How good is that for your ego?

Second, the experience of a new place in the company of people whose concern at that moment is with the world of literature – not politics, finance, or mothers-in-law -- is one of the greatest pleasures imaginable.

Last week I was in the Rhineland city of Cologne at the invitation of the Cologne-Bethlehem Twin Cities Association. Each year on Epiphany (which celebrates the arrival of the Three Kings in Bethlehem, following the star to Jesus’s manger) they arrange a reading related to Bethlehem. That’s because the bones of the Three Kings are kept in Cologne’s astonishing Gothic cathedral. This year they picked “Der Verraeter von Bethlehem,” which you may know as my first Palestinian crime novel “The Collaborator of Bethlehem” (UK title: “The Bethlehem Murders”).

I arrived late at night and did a few interviews in the morning with local press. Then I strolled (if you can really stroll in minus-5 degrees whipping of the river) to the cathedral with Saskia Heinemann, a Cologne-native who works for my Munich publisher Beck Verlag.

Inside, the high vaults of the ceiling were loaded with incense. Three youngsters dressed as the Three Kings were singing “Gloria in Excelsis Deo” to a surprisingly packed congregation. After the priest’s blessing everyone filed behind the altar to the golden shrine where the bones of the Three Wise Men are kept. It glimmered behind a trio of candles marked with the initials of Caspar, Balthasar and Melchior. The cathedral organ played joyously and the bells joined in.

I never take part in any kind of ritual (except for the way I make espresso every morning). As a journalist I watch rituals. As a writer I’m always somehow outside, too, making notes for a way to use such a scene in a future book. This time I found myself moved to be shuffling among the crowd, looking up at the massive columns and stained glass. Somehow I was watching and listening and smelling all the happy Christmases I haven’t had, the unhappy emptiness in which for many people the urge to be a writer is nurtured. But that’s a subject for another time….

Cologne was almost entirely destroyed in WWII. Miraculously the cathedral suffered little damage. The town’s collection of beautiful Romanesque churches (I particularly loved Gross St. Martin) were rebuilt from what remained. Out of reach of the bombs, beneath the town hall square, the oldest synagogue in Europe was recently discovered. I watched through the side of the marquee where the remains are being unearthed by a freezing group of archeologists.

In the traditional beerkeller Frueh, I warmed up with leberknoedel soup and Haemchen, which is essentially the upper back leg of a pig, boiled. I peeled away the layers of fat, white as an Englishman’s tummy, and a large burnt-umber glob which was apparently clotted blood. Then I put away a good few pounds of delicious, salty, soft ham.

Before my reading that night at the Ludwig bookshop in the main station, Miriam Froitzheim arrived from nearby Aachen with a consignment of Printen, the best cookies in Germany. They’re sweetened with honey, not sugar, and covered in a rich chocolate.

The reading was a welcome opportunity to discuss my first novel – which sometimes seems like ancient history to me, as I’ve written four more (one still in manuscript form) since then. Still it was only published in English in 2007 and, in Germany, two years ago.

I dined with some of the bookshop staff, and Udo Hombach, the retired music teacher who read a couple of chapters from my book in German for the audience. An aficionado of churches built by the last Kaiser (several in the Rhineland, and a couple of notable ones in Jerusalem, including the Ascension Church where I did a reading recently and admired the massive ceiling mosaic of Kaiser Wili himself) turned artist, Udo produced a handful of colorful mosaic tiles from his waistcoat pocket. His father had gathered them from the ruins of one of the Kaiser’s churches in Berlin after a bombing raid. Now Udo uses them to make mosaics for his gallery. (You can find it Am Roemerturm 15 in Cologne.)

The following day I nipped around the Museum Ludwig in central Cologne. It’s one of the greatest collections of Expressionist art. That was a change from the Renaissance art in which I’ve been immersed of late, and the building itself is light and spacious, a little like the cathedral next door. Even the luggage lockers were avant garde (the numbers were on the inside, so you kind of had to guess...).

Then I zipped off to the airport feeling very content. You see, at my reading, a woman pointed to the author photo on the jacket and said: “You look much better in real life.”

Wall St Journal on 'The Fourth Assassin'

While in New York this last couple of weeks, I stopped into the space-age HQ of Rupert Murdoch's News Corp on the Avenue of the Americas in Midtown Manhattan. Once my eyes had adjusted to the superbright white light everywhere, I settled into a studio for an interview with Jon Friedman (the man known around NY as "Mister Media") to talk about how I researched my new novel THE FOURTH ASSASSIN.

Published on February 09, 2010 05:24

•

Tags:

book-research, brooklyn, jon-friedman, marketwatch, matt-beynon-rees, middle-east, new-york, omar-yussef, the-fourth-assassin, the-wall-street-journal, travel, video, writing

Urinal-top video

We were on the Hessian plain somewhere outside Frankfurt when I felt as though the drugs had taken hold.

We were on the Hessian plain somewhere outside Frankfurt when I felt as though the drugs had taken hold.Why am I paraphrasing the great Hunter S. Thompson? Because I endured an experience that Professor Gonzo could only have imagined in his wildest LSD frenzies. Something that made me feel I must be hallucinating, as if the Las Vegas of HST’s fear and loathing had come to me, cleaned up and waterless but every bit as insidious. What I saw was proof that we have no limits in our power to suck every last cent out of every possible human moment.

I was urinating. Into a urinal. At a rest stop outside Germany’s business capital. When I looked down, I didn’t see the accustomed maker’s logo. No, there was a video screen. About six inches across and four inches high. Bright, bright high-definition. Built into the top of the urinal. Advertising itself as the product of Urimat.com.

They’re insidious, these Urimat people, I tell you, brother urinator. They must’ve done years of research to assess exactly where males let their eyes drop when peeing. It’s not on your unit. No, because that necessitates looking at the disgusting mess of the urinal itself, the chewing gum and receipt papers and hairs, oh God the curly hairs. We look higher than that. But not so high that we must confront the wall in front of us, with its vicious graffiti and its smears of nose-booger.

We look right at the top of the urinal, we brothers in urination. And the bastards at Urimat thought: Why waste all that time, when men are looking at nothing? Let’s make them look at a housewife, scrubbing her kitchen and bathroom. Let’s make them watch as “The dirt goes, the aroma stays.”

Can’t you picture Baron Urimat now, in his boardroom overlooking Feldbachstrasse in Feldbach, Switzerland – for this is where they have their evil mountain lair – saying to his henchmen: “When they have their dirty little units in their hands, the path to men’s minds lies open. Let us feed this psychological emptiness. Before they put themselves back in their pants and walk out without washing their hands. Let us take control of their minds.”

Can't you hear the evil cackles of laughter even now?

Read the rest of this post on my blog The Man of Twists and Turns.<\a>

Published on October 07, 2010 06:20

•

Tags:

book-tour, fear-and-loathing-in-las-vegas, germany, hunter-s-thompson, lsd, professor-gonzo, travel, urimat