Matt Rees's Blog - Posts Tagged "raymond"

"Mystery fiction not limited by form, highly instructive"

People who don't know any better sometimes tell me that I'm a good writer and they'd like to see me write a "real novel," instead of my Palestinian crime novels. Usually I tell them Raymond Chandler once wrote that there are just as many bad "real" literary novels written as bad mysteries -- but the bad literary novels just don't get published. Now I'll be able to add something else to my always polite correction of this misconception about crime novels. That's because of a review of my new Palestinian crime novel THE SAMARITAN'S SECRET in the Feb. 7 issue of The Tablet, a British magazine published for the Roman Catholic community. The Tablet makes THE SAMARITAN'S SECRET "Novel of the Week" and reviewer Anthony Lejeune writes that it's "a novel thick with atmosphere, memorable, unusual and the clearest possible proof that mystery fiction can be moulded into any literary form and is often highly instructive."

My 5 favorite novels

My second Palestinian crime novel A Grave in Gaza (UK title: The Saladin Murders) is just now published in Holland. The Dutch newspaper de Volkskrant asked me to contribute a list of my five favorite books, or at least those which've had the biggest impact on me as a writer. Here's what I wrote:

Let It Come Down – Paul Bowles

Writers look for resonance. You might say Bowles has us with his title alone, which resonates with doom even before he writes his first sentence. (It’s drawn from “MacBeth.” When the murderers come upon Banquo, he says that it looks like there’ll be rain. The murderer lifts his knife and says: “Let it come down.” Then he kills him.) But with this novel about Morocco, as in his more famous Algerian novel “The Sheltering Sky”, Bowles was even more resonant. When writing, he would often travel through North Africa. Each day, he would incorporate something into his writing that had actually happened during the previous day’s journey. Working in the Middle East, I often follow that technique, adding details from yesterday’s stroll through the Muslim Quarter of Jerusalem or a refugee camp in Bethlehem.

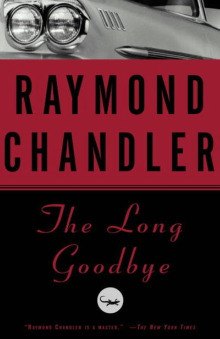

The Long Goodbye – Raymond Chandler

This is the novel that Chandler labored over longest and thought his best. He was right. It exposes a deep emotional side to his great detective creation Philip Marlowe. Chandler was the greatest stylist of Twentieth Century American fiction. Try this image, when a beautiful woman has just walked into a bar full of men and everyone falls silent to look at her: “It was like just after the conductor taps on his music stand and raises his arms and holds them poised.” Chandler inspires me to make every image in my book as good as that.

The King Must Die – Mary Renault

I was heading for Jordan to cover the dieing days of King Hussein a decade ago. I happened to pick up a used copy of this book -- the title seemed appropriate. But as I waited in a rainy Amman winter for the poor old monarch to die, I discovered that Renault had a capacity to describe the classical world as though she had lived through that era. Her novels are the best portrayal of homosexual love and of the great values of Greece in literature anywhere.

The Cold Six Thousand – James Ellroy

I love to see real characters from Hollywood and Washington turn up in Ellroy’s terse, hip, hardboiled poetic fiction. This story of CIA/FBI renegades in the aftermath of the Kennedy assassination is perfect. I saw Ellroy read years ago in New York and he blew me away. If you can find a better opening paragraph to a chapter than this one, let me know: “Heat. Bugs. Bullshit.” Dig it.

The Power and the Glory – Graham Greene

Greene went to Mexico to research a travel book, but he showed that journalistic research can turn into literature of great spirituality with this story of a drunken priest on the run. I try to remember that as I flick through my old reporter's notebooks for new ideas for my novels. Greene's is such a powerful examination of the loss of belief that it captivates even a non-Catholic, non-believer like me. The scene where the priest steals a hunk of meat from a stray dog is astonishing. The priest starts to beat the dog: “She just had to endure, her eyes yellow and scared and malevolent shining back at him between the blows.” Like Mexico under dictatorship. Like the priest before a disapproving God.

Let It Come Down – Paul Bowles

Writers look for resonance. You might say Bowles has us with his title alone, which resonates with doom even before he writes his first sentence. (It’s drawn from “MacBeth.” When the murderers come upon Banquo, he says that it looks like there’ll be rain. The murderer lifts his knife and says: “Let it come down.” Then he kills him.) But with this novel about Morocco, as in his more famous Algerian novel “The Sheltering Sky”, Bowles was even more resonant. When writing, he would often travel through North Africa. Each day, he would incorporate something into his writing that had actually happened during the previous day’s journey. Working in the Middle East, I often follow that technique, adding details from yesterday’s stroll through the Muslim Quarter of Jerusalem or a refugee camp in Bethlehem.

The Long Goodbye – Raymond Chandler

This is the novel that Chandler labored over longest and thought his best. He was right. It exposes a deep emotional side to his great detective creation Philip Marlowe. Chandler was the greatest stylist of Twentieth Century American fiction. Try this image, when a beautiful woman has just walked into a bar full of men and everyone falls silent to look at her: “It was like just after the conductor taps on his music stand and raises his arms and holds them poised.” Chandler inspires me to make every image in my book as good as that.

The King Must Die – Mary Renault

I was heading for Jordan to cover the dieing days of King Hussein a decade ago. I happened to pick up a used copy of this book -- the title seemed appropriate. But as I waited in a rainy Amman winter for the poor old monarch to die, I discovered that Renault had a capacity to describe the classical world as though she had lived through that era. Her novels are the best portrayal of homosexual love and of the great values of Greece in literature anywhere.

The Cold Six Thousand – James Ellroy

I love to see real characters from Hollywood and Washington turn up in Ellroy’s terse, hip, hardboiled poetic fiction. This story of CIA/FBI renegades in the aftermath of the Kennedy assassination is perfect. I saw Ellroy read years ago in New York and he blew me away. If you can find a better opening paragraph to a chapter than this one, let me know: “Heat. Bugs. Bullshit.” Dig it.

The Power and the Glory – Graham Greene

Greene went to Mexico to research a travel book, but he showed that journalistic research can turn into literature of great spirituality with this story of a drunken priest on the run. I try to remember that as I flick through my old reporter's notebooks for new ideas for my novels. Greene's is such a powerful examination of the loss of belief that it captivates even a non-Catholic, non-believer like me. The scene where the priest steals a hunk of meat from a stray dog is astonishing. The priest starts to beat the dog: “She just had to endure, her eyes yellow and scared and malevolent shining back at him between the blows.” Like Mexico under dictatorship. Like the priest before a disapproving God.

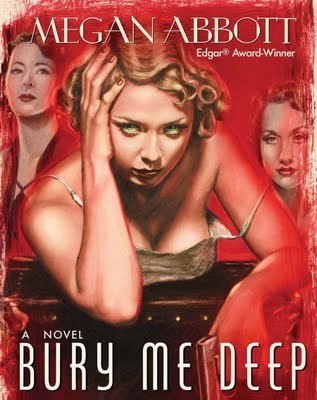

Ellroy Queen: Megan Abbott’s Writing Life

Megan Abbott is the female James Ellroy. When I read her Edgar-award-winning “Queenpin,” I immediately was put in mind of everyone’s favorite noirmeister. Dig it. Even more I loved “The Song is You,” in which Abbott took a real-life missing persons case from 1949 and plumbed her Hollywood characters for real debauchery and dirt like Ellroy at his best. Dr. Abbott (she has a Ph.D. in English and American Literature from New York University) has a great new one that’s a US Independent Booksellers pick for August. As for how she does it, read on, checking out her particularly intriguing writing exercise. As someone might write: Off the record, on the Q.T., and very hush, hush.

How long did it take you to get published?

I wrote for years without finishing anything or knowing what to do with it. Once I finished a novel, it took about a year or so to get an agent and sell it. I was both stupid and lucky. Stupid because I had no idea how hard it would be, and lucky because I found an agent and an editor willing to take a chance.

Would you recommend any books on writing?

I’m sure there are good ones, but, for me, reading novels all the time is much more helpful. I once had a teacher who had us do this exercise I always remember because I use it to this day. He had us pick a favorite passage by an author and rewrite the passage by replacing every word. A noun for a noun, a verb for a verb, and so forth. I took a passage from F. Scott Fitzgerald. It was staggering how much it forced my writing out of an old rhythm and into a new one. I did it a lot with Raymond Chandler novels once I discovered them. It breaks you out of ruts and you pick up this range of cadences

What’s a typical writing day?

I start about eight in the morning and then waste many, many hours—much time lost on thesaurus.com, on following endless research trails—I collect a lot of things: old menus from the 1920s, photos of friars’ roasts from the turn of the century, abandoned diaries. I get lost in them and it can, easily, take me four hours to produce a page, and when I do, it’s usually in a mad rush inspired by guilt for all that procrastinating.

Plug your latest book. What’s it about? Why’s it so great?

It’s a strange little tabloid tale loosely based on a famous real-life crime from the 1930s—the Winnie Ruth Judd “Trunk Murderess” case. It’s called Bury Me Deep and it follows Marion Seeley, a young woman left by her husband in Phoenix at the height of the Great Depression. Very naïve, very lonely, she falls in with two of the town’s single gals, gals with reputations: Soon enough, she’s swept up in their freewheeling lifestyle, the “thrill parties” they throw. At one of these parties, she meets and falls hard for charming Joe Lanigan, a rising town leader who proves her downfall.

How much of what you do is:

a) formula dictated by the genre within which you write?

b) formula you developed yourself and stuck with?

c) as close to complete originality as it’s possible to get each time?

I am a genre lover—so much so that I like to knock them together. For Bury Me Deep, for instance, the idea was to merge a very traditional melodrama—a woman who faces this almost Edith-Wharton-style dilemma (follow society’s rules or one’s own heart) with a down-and-dirty pulp story of drugs, sin and murder. I think it’s probably true in all my novels—with the possible exception of Queenpin, which I tried to make as close as possible to classic pulp fiction. I think all genres are in many ways one genre, with different accessories. In the end, we’re all fighting social rules, society itself, or all fighting ourselves—which is kind of the same thing.

What’s your favorite sentence in all literature, and why?

Did you ever have a sister, from Faulker’s The Sound and the Fury. In a book swollen with words, twisting and curling on themselves, pounding and thundering—it can still be gathered into in that simple line. And, when that line comes—which it does, more than once—it’s a heartbreaker.

What’s the best descriptive image in all literature?

Humbert Humbert describing Lolita’s feet, or Raymond Chandler describing almost anything.

Who’s the greatest stylist currently writing?

Daniel Woodrell.

Who’s the greatest plotter currently writing?

I guess I don’t really read for plot. In fact, many of my favorite books have rambling, meandering plots.

How much research is involved in each of your books?

For the historical ones—set in the 1930s-60s—a lot, but not in any coordinated way. For Bury Me Deep, I read a lot about TB hospitals and morphine addiction. Then, after a few months, I stop researching and start writing—it’s hardest for me to both at the same time.

Where’d you get the idea for your main character?

She’s modeled on her real-life counterpart, Winnie Ruth Judd, but Marion ends up veering pretty wildly. There was only so much I could find out about what went on in Winnie Ruth’s head, so I ended up making up the rest and soon enough Marion was all her own.

Do you have a pain from childhood that compels you to write? If not, what does?

Only boredom. I had a wonderful childhood with great, creative parents and brother, but it was old-school suburbia and I wasn’t imaginative enough to find the magic in it. I felt like I was just killing time.

What’s the best idea for marketing a book you can do yourself?

Golly, I have no idea. You tell me.

What’s your experience with being translated?

It’s fun to see the editions and see if/how they package it differently. I have no idea if those pages correspond to what I wrote, which is kind of a neat feeling.

Do you live entirely off your writing? How many books did you write before could make a living at it?

No. I work at a nonprofit four days a week and it keeps me honest and “in the world.” I have trouble being at home all day, living in my head. I think that requires a mental strength I don’t have.

How many books did you write before you were published?

No finished ones. But dozens of false starts and embarrassments.

What’s the strangest thing that happened to you on a book tour?

I arrived in Scottsdale, Arizona with Vicki Hendricks, famous for her wonderful and very sexually explicit noir novels. It was over 100 degrees and we had a little time before our signing so we strolled into a nearby, nearly empty bar for a soda. Within ten minutes, a very drunk young man at the bar (it was only noon) kept talking to us and he confessed he was going to jail the following day. Then, he pulled down his pants to show us the tattoo on his bare bottom—the one he was sure was going to doom him in jail. It was a big beating heart and, of course, it said, “Mom.”

What’s your weirdest idea for a book you’ll never get to publish?

I never think any of my book ideas will lead to publication!

Published on August 25, 2009 07:53

•

Tags:

chandler, crime, ellroy, fiction, film, hardboiled, interviews, james, life, literature, new, raymond, writing, york

Outrage: Raymond Chandler in the trash

The last decade has been one of outrage piled upon outrage, from 9/11 to the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq, on to Hurricane Katrina, the Asian tsunami and the smart-ass bankers who thought they ruled the world they were in the process of destroying. On the first day of the new decade I was faced with something less outrageous, perhaps, but somehow even more puzzling than any of these things.

The last decade has been one of outrage piled upon outrage, from 9/11 to the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq, on to Hurricane Katrina, the Asian tsunami and the smart-ass bankers who thought they ruled the world they were in the process of destroying. On the first day of the new decade I was faced with something less outrageous, perhaps, but somehow even more puzzling than any of these things.I was walking along a street near my home in Jerusalem with a friend. A few paperbacks had been dropped on the ground by a dumpster. I glanced down. "That can't be," I thought. Then, aloud, I said: "You're kidding me."

Someone had thrown out "The Long Goodbye." Someone had put Raymond Chandler in the trash, with a few highly disposable beach-reading tomes. I picked it up gently.

For me this is the greatest American novel of the last century, yet it was sitting alongside the kinds of holiday reading people tend to ditch as soon as they've skimmed to the "exciting" conclusion.

Chandler would've raised one of his wry eyebrows, or perhaps one of the gimlets that appears as a motif in "The Long Goodbye." He knew what people thought of his work--those who hadn't read it at least. Not real literature, genre stuff. People say the same thing to me sometimes, until they read my books. Chandler once wrote that as many bad "literary" novels are written as there are bad crime novels, but the bad literary novels don't get published. (One might note that this no longer seems true, but you get his point: people thought his books were trash, like the genuine trash that was sold alongside it.)

Why's his novel so good? Many reasons, not least of which is Chandler's astonishing way with an image. Try this one: a beautiful woman has just walked into a bar where sleuth Marlowe awaits a client. "It seemed to me for an instant that there was no sound in the bar," Chandler writes, "that the sharpies stopped sharping and the drunk on the stool stopped burbling away, and it was like just after the conductor taps on his music stand and raises his arms and holds them poised."

You don't even have to be a male who once sat lonely in a dingy dive for that sentence to stop everything--the narrative, your breath, your heart. Turns out the woman will be an important character. We don't know it yet for sure, but somehow it's been signaled by the punctuation point of this image.

The friend I was walking with declined at first to take "The Long Goodbye," when I proferred the grubby edition. "I don't really read crime novels," he said.

I shoved it into his midriff. "Read it," I said. "It's a masterpiece."

Then I looked at the other books on the floor. Sometimes around where I live people dispose of the library of a deceased person by placing it on the street for others to pick up. I shook my head. Even when I die, I don't want my copy of "The Long Goodbye" left in the dust and wind of a desert winter.

I want to be buried with it.