Matt Rees's Blog - Posts Tagged "beynon"

Toronto Star: Palestinian crime novels the key to happiness

Toronto Star Mideast correspondent Oakland Ross writes about my path to happiness -- via the less than happy occurrences of the region. It's a different, more personal kind of profile than the sort of thing journalists usually write, which is perhaps due to the novelist's sensibility Oakland brings to the piece (He's the author of historical novels set in Mexico.)

Welsh writer quit Time magazine to pen books in popular sleuth series

May 27, 2009 Oakland Ross MIDDLE EAST BUREAU

JERUSALEM–Happiness did not find Matt Beynon Rees.

Instead, Matt Beynon Rees found happiness.

First, however, he was obliged to travel to the Middle East, not a region of the world noted for an over-abundance of glee. Read more...

Welsh writer quit Time magazine to pen books in popular sleuth series

May 27, 2009 Oakland Ross MIDDLE EAST BUREAU

JERUSALEM–Happiness did not find Matt Beynon Rees.

Instead, Matt Beynon Rees found happiness.

First, however, he was obliged to travel to the Middle East, not a region of the world noted for an over-abundance of glee. Read more...

Grassroots signs for my Palestinian crime novels

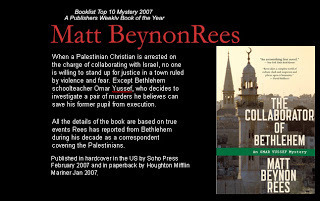

A new review in the Ann Arbor Chronicle suggests healthy grassroots popularity for my Palestinian crime novels. The review of my first Palestinian crime novel "The Collaborator of Bethlehem" (UK Title: The Bethlehem Murders) is written by Robin Agnew, owner of Aunt Agatha's Mystery Bookstore in Ann Arbor. She writes: "When enough customers ask you about a certain author in a short period of time, it makes you take notice. When several of my more discerning “guy” readers mentioned Matt Rees as a wonderful writer, I was intrigued enough to pick up the first book."

Robin goes on to say:"Rees is able – like the very best of novelists – to convey absolute horror without sentimentality. Some of the things that happen in this book will probably haunt you, but they also seem like things that can and do happen. The real bit of grace in the book is the way Yussef chooses to deal with what happens. He shows that even a somewhat frail 56 year old can find a reason to move ahead in the world. I can’t recommend this book highly enough." Read the full review in The Ann Arbor Chronicle.

The Last Man in London

Here's my latest post on the International Crime Authors Reality Check blog:

During my teens, my family lived in a house in Addington, at the very farthest reach of South London. At the bottom of the hill, the road made its final exit from London. Not quite wide enough for two cars, it traveled onto the North Downs of Kent. Sometimes I would ride my bike along the lane and up a hill overlooking the Downs and lie on the grass. I was the border between London and the rest of the world. When a car went by below, I’d send out a silent message to the driver: “You just passed the last man in London.”

Much of my time was spent looking in the opposite direction, wishing we lived in central London– where things happened, where the Underground came to your neighborhood, where there was life, damn it. Where I would feel at one with those around me. Not like “the last man,” the one at the edge of everything. Like any suburban teenager, I wanted to be anywhere else in the world but where I was. And central London was both elsewhere and not impossibly far away.

Most of my friends from that time and from university, too, ended up living and working right there in central London. Perhaps they knew it was the right place for them, or maybe they never cared to ask themselves that question. I knew it wasn’t what I wanted, and I never lived there. I went down the lane that wasn’t wide enough for two cars, and I never came back. If I hadn’t, I’m sure I’d still have written. But I doubt I would have seen as much or learned what I have about myself.

The Palestinian sleuth of my crime novels Omar Yussef is, for me, a satisfying character because he represents the insights I’ve gathered in distant, eventful travels. But he’s also a measure of my ability to understand the outsiders of other cultures. Not the people journalists typically rush toward–the prime ministers and generals and imams with their false rhetoric and their stake in things staying as they are. Rather they’re the people who seem to climb the same marginal hill that I mounted as a youth and look out wondering why their world isn’t better than it is. That’s the essence of Omar Yussef (and of the best “exotic detective” fiction).

That lane near our house went up onto the Downs and undulated toward Westerham, a beautiful place built around a sloping village green. At the center of the green, there’s a statue of General Wolfe, a native of the village who led British troops to victory against the French in Canada in the Seven Years War of the mid-Eighteenth Century. The latest historical research on Wolfe suggests he was a megalomaniac glory-hunter who got exactly the kind of heroic immortality he wanted when he died at the moment of victory in Quebec.

I haven’t paid the price exacted of Wolfe. (But then, no one’s built any statues of me, either.) I’ve been stoned, abused, hectored, threatened, held at gunpoint. I’ve come out of it with the kind of knowledge granted only to one of those who never expected to be loved by everyone and yet was never driven by hate–namely, an observant outsider.

The sense of being an outsider I experienced as the Last Man in London was alienating back then. But in Bethlehem and Gaza it still gives me a sense for the outsiders—whether that’s the Palestinians without their state, or the minorities who live among them, like the Christian Palestinians featured in THE COLLABORATOR OF BETHLEHEM or the few hundred Samaritans who live on a hill overlooking Nablus and are at the center of THE SAMARITAN’S SECRET. It helped me identify the people who could teach me the most about myself, to build a bond of trust with them and understand them. It also led me to write the Omar Yussef mysteries as a direct challenge to every accepted Western idea about the Palestinians.

And to every idea I ever had about me. But that’s for another blog…

During my teens, my family lived in a house in Addington, at the very farthest reach of South London. At the bottom of the hill, the road made its final exit from London. Not quite wide enough for two cars, it traveled onto the North Downs of Kent. Sometimes I would ride my bike along the lane and up a hill overlooking the Downs and lie on the grass. I was the border between London and the rest of the world. When a car went by below, I’d send out a silent message to the driver: “You just passed the last man in London.”

Much of my time was spent looking in the opposite direction, wishing we lived in central London– where things happened, where the Underground came to your neighborhood, where there was life, damn it. Where I would feel at one with those around me. Not like “the last man,” the one at the edge of everything. Like any suburban teenager, I wanted to be anywhere else in the world but where I was. And central London was both elsewhere and not impossibly far away.

Most of my friends from that time and from university, too, ended up living and working right there in central London. Perhaps they knew it was the right place for them, or maybe they never cared to ask themselves that question. I knew it wasn’t what I wanted, and I never lived there. I went down the lane that wasn’t wide enough for two cars, and I never came back. If I hadn’t, I’m sure I’d still have written. But I doubt I would have seen as much or learned what I have about myself.

The Palestinian sleuth of my crime novels Omar Yussef is, for me, a satisfying character because he represents the insights I’ve gathered in distant, eventful travels. But he’s also a measure of my ability to understand the outsiders of other cultures. Not the people journalists typically rush toward–the prime ministers and generals and imams with their false rhetoric and their stake in things staying as they are. Rather they’re the people who seem to climb the same marginal hill that I mounted as a youth and look out wondering why their world isn’t better than it is. That’s the essence of Omar Yussef (and of the best “exotic detective” fiction).

That lane near our house went up onto the Downs and undulated toward Westerham, a beautiful place built around a sloping village green. At the center of the green, there’s a statue of General Wolfe, a native of the village who led British troops to victory against the French in Canada in the Seven Years War of the mid-Eighteenth Century. The latest historical research on Wolfe suggests he was a megalomaniac glory-hunter who got exactly the kind of heroic immortality he wanted when he died at the moment of victory in Quebec.

I haven’t paid the price exacted of Wolfe. (But then, no one’s built any statues of me, either.) I’ve been stoned, abused, hectored, threatened, held at gunpoint. I’ve come out of it with the kind of knowledge granted only to one of those who never expected to be loved by everyone and yet was never driven by hate–namely, an observant outsider.

The sense of being an outsider I experienced as the Last Man in London was alienating back then. But in Bethlehem and Gaza it still gives me a sense for the outsiders—whether that’s the Palestinians without their state, or the minorities who live among them, like the Christian Palestinians featured in THE COLLABORATOR OF BETHLEHEM or the few hundred Samaritans who live on a hill overlooking Nablus and are at the center of THE SAMARITAN’S SECRET. It helped me identify the people who could teach me the most about myself, to build a bond of trust with them and understand them. It also led me to write the Omar Yussef mysteries as a direct challenge to every accepted Western idea about the Palestinians.

And to every idea I ever had about me. But that’s for another blog…

New Republic: The Samaritan's Secret a 'wonderful detective thriller'

In his New Republic blog, the magazine's honcho Marty Peretz rightly rails at the failure of the Fatah Party to agree on anything at its conference this week in Bethlehem -- except that Israel killed Arafat. Rails because, of course, that's not going to reform this corrupt bunch of villains who're currently clogging Manger Square with their swanky wheels, nor is it going to improve the daily life of ordinary Palestinians one bit. Peretz then notes: "If you want to read a wonderful detective thriller by Matt Beynon Rees, whom L'Express called "the Dashiell Hammet of Palestine," pick up The Samaritan's Secret, in which Arafat's late life and death lurk as vivid presence and macabre ghost."

Published on August 06, 2009 22:37

•

Tags:

beynon, blogs, east, fatah, ghosts, matt, middle, palestine, palestinians, plo, rees, samaritan-s, samaritans, secret

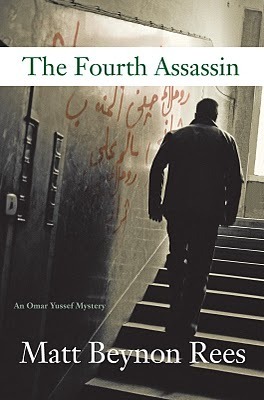

THE FOURTH ASSASSIN on video

To introduce the next of my Palestinian crime novels, THE FOURTH ASSASSIN, my friend videographer David Blumenfeld filmed in New York (where the book takes place). His montages are mainly from Brooklyn's Bay Ridge and Coney Island sections. He then recorded me, looking sweaty and frankly a bit doped up, in my favorite seedy cafe in Jerusalem's Muslim Quarter.

You can view it here, and if you prefer you can watch it in French, German, or Italian. THE FOURTH ASSASSIN will be published in the UK and US in February, but I just couldn't keep my video a secret until then.

You can view it here, and if you prefer you can watch it in French, German, or Italian. THE FOURTH ASSASSIN will be published in the UK and US in February, but I just couldn't keep my video a secret until then.

'Smart People Recommend'...Me

On The Daily Beast's Buzz Board, under the headline "Smart People Recommend", Charles M. Sennott, head honcho of the innovative international news site Global Post, plugs THE SAMARITAN'S SECRET: "Matt Beynon Rees’s Palestinian detective novels reveal more truths about the 'Holy Land,' and I use that term loosely, than any straight journalism I’ve ever read [Sennott writes:]. He is a masterful storyteller with the eye for detail of a great reporter, which he is as well. They are a collection of stories featuring the fictional detective, Omar Yussef, whose life is full of the complexities and contradictions and humanity that are the ground truth of life in Israel/Palestine. Check out The Samaritan’s Secret."

Neon pee on the Reeperbahn, and other travels

The whole point of travel is to see Red Light districts around the world. That’s what I assume my German publisher C.H. Beck thinks. Or maybe that's what they think I'll like. Anyway, they keep sending me to Hamburg, which has one of the most famous naughty neighborhoods in the world.

At the invitation of the extremely professional Harbour Front Literaturfestival and in the company of my Beck “handler,” I made another visit to Hamburg last month. I really like the place tremendously. Not because of the Reeperbahn, the red light strip, but because the city faces the wide River Elbe in every sense, it’s affordable, and its people are liberal and open.

That’s a very pleasant change for me, given that I live in the Middle East, a region where there’s no water, things are quite expensive, and the people… Well, I think you’ve read about them.

I wandered the Reeperbahn with Miriam Froitzheim, the wonderful Beck lady whose job is to get me on the right trains, feed me, and pretend that it isn’t boring for her to listen to my same shtick every night at my readings. We particularly enjoyed the public toilet on the center-island of the road, which was decorated with two little neon boys peeing pink neon streams of urine at each other.

Other than that, it must be said that red light districts put me in mind less of sex than they do of sexually transmitted disease. Not to mention theft and violence. I gave some money to a beggar because it seemed better than putting it in the slot of a peep-show and headed for the river.

I stayed a couple of nights on the Cap San Diego, a 1920s ocean liner which is now a floating hotel in the heart of Hamburg’s docks (It goes downriver to the sea twice a year). It’s only 80 Euros a night, which makes it pretty cheap for a hotel anywhere in Europe. Its comfortable wooden interiors look out onto the cranes of the dockyard across the rolling Elbe.

You can see the yacht Roman Abramovic (Russian oligarch owner of a boring English soccer club) is building at 1 million Euros a meter, which is less than what he pays for soccer players but still quite expensive. It’ll be 150 meters long when it's finished early in the winter. Along the river is a new Philharmonic building, which probably cost less than the yacht and isn’t crass or disgusting.

From my porthole, I also watched boats ferrying people to the theater on the other side of the river. Now showing, “The Lion King”: a nine-year run, booked six months ahead. Another boat went by advertising “Tarzan,” a musical with songs by Phil Collins which was cast on a German tv reality show.

I commented to Miriam that I’m insulated from such pop-cultural crap. By living in Jerusalem, a city where nothing ever happens. Except terrorism.

She used the opportunity to introduce me to a very useful German expression: “Was bringt dich auf die Palme?” Literally, what sends you up a palm tree? (ie. What drives you nuts?) Answer: Phil Collins musicals, of course.

En route to Hamburg, my train stopped in Hannover. Throughout the intifada, I drove a Mercedes armored car through the West Bank. It had Hannover plates (I’d imported it from Germany). I gave a quiet thanks to the town which had stopped a few bullets for me.

Then it was off to Aachen, near the Dutch border, where my reading was in Charlemagne’s 1200-year-old hunting lodge, the Frankenbergerhof. Charlemagne is the main man in Aachen. His throne sits in the town’s cathedral, which is a beautiful hodge-podge that looks enormous on the outside and is quite small on the inside. Unless the Aachners were hiding some part of it from me.

They also have the Devil’s thumbprint on the door of the cathedral. That happened when Lucifer got his finger caught in the door. The Devil being that stupid, you see.

Opposite the lovely Aachen town hall, I sat for lunch at the Brauerei Goldener Schwan. While some may travel for red light districts, I go for the food. I ate Aachner puttes, also known as Himmel und Erd (Heaven and Earth): blood sausage of a very soft consistency, fried onions, fried apples, and mashed potatos. More Himmel than Erd, I’d say.

I worked off the “puttes” by wandering Aachen with Miriam, a native of the town. Actually I didn’t really walk off the lunch. As we strolled, we bought a packet of Aachner Printen, the clovey gingerbread-like cookies for which the town is famed (not really gingerbread, which is sweetened with honey; these are sweetened with sugar). So on balance I probably got fatter in Aachen.

But at least no one peed neon at me.

Next post: I finish my German-language reading tour in Switzerland and actually take a vacation for the first time in two years, bumping into someone who used to play football for Roman Abramovic… Next post after that: I field emails from people telling me that reading tours sound much like vacations, so I oughtn’t to complain that it’s been two years since I had a formal break….

At the invitation of the extremely professional Harbour Front Literaturfestival and in the company of my Beck “handler,” I made another visit to Hamburg last month. I really like the place tremendously. Not because of the Reeperbahn, the red light strip, but because the city faces the wide River Elbe in every sense, it’s affordable, and its people are liberal and open.

That’s a very pleasant change for me, given that I live in the Middle East, a region where there’s no water, things are quite expensive, and the people… Well, I think you’ve read about them.

I wandered the Reeperbahn with Miriam Froitzheim, the wonderful Beck lady whose job is to get me on the right trains, feed me, and pretend that it isn’t boring for her to listen to my same shtick every night at my readings. We particularly enjoyed the public toilet on the center-island of the road, which was decorated with two little neon boys peeing pink neon streams of urine at each other.

Other than that, it must be said that red light districts put me in mind less of sex than they do of sexually transmitted disease. Not to mention theft and violence. I gave some money to a beggar because it seemed better than putting it in the slot of a peep-show and headed for the river.

I stayed a couple of nights on the Cap San Diego, a 1920s ocean liner which is now a floating hotel in the heart of Hamburg’s docks (It goes downriver to the sea twice a year). It’s only 80 Euros a night, which makes it pretty cheap for a hotel anywhere in Europe. Its comfortable wooden interiors look out onto the cranes of the dockyard across the rolling Elbe.

You can see the yacht Roman Abramovic (Russian oligarch owner of a boring English soccer club) is building at 1 million Euros a meter, which is less than what he pays for soccer players but still quite expensive. It’ll be 150 meters long when it's finished early in the winter. Along the river is a new Philharmonic building, which probably cost less than the yacht and isn’t crass or disgusting.

From my porthole, I also watched boats ferrying people to the theater on the other side of the river. Now showing, “The Lion King”: a nine-year run, booked six months ahead. Another boat went by advertising “Tarzan,” a musical with songs by Phil Collins which was cast on a German tv reality show.

I commented to Miriam that I’m insulated from such pop-cultural crap. By living in Jerusalem, a city where nothing ever happens. Except terrorism.

She used the opportunity to introduce me to a very useful German expression: “Was bringt dich auf die Palme?” Literally, what sends you up a palm tree? (ie. What drives you nuts?) Answer: Phil Collins musicals, of course.

En route to Hamburg, my train stopped in Hannover. Throughout the intifada, I drove a Mercedes armored car through the West Bank. It had Hannover plates (I’d imported it from Germany). I gave a quiet thanks to the town which had stopped a few bullets for me.

Then it was off to Aachen, near the Dutch border, where my reading was in Charlemagne’s 1200-year-old hunting lodge, the Frankenbergerhof. Charlemagne is the main man in Aachen. His throne sits in the town’s cathedral, which is a beautiful hodge-podge that looks enormous on the outside and is quite small on the inside. Unless the Aachners were hiding some part of it from me.

They also have the Devil’s thumbprint on the door of the cathedral. That happened when Lucifer got his finger caught in the door. The Devil being that stupid, you see.

Opposite the lovely Aachen town hall, I sat for lunch at the Brauerei Goldener Schwan. While some may travel for red light districts, I go for the food. I ate Aachner puttes, also known as Himmel und Erd (Heaven and Earth): blood sausage of a very soft consistency, fried onions, fried apples, and mashed potatos. More Himmel than Erd, I’d say.

I worked off the “puttes” by wandering Aachen with Miriam, a native of the town. Actually I didn’t really walk off the lunch. As we strolled, we bought a packet of Aachner Printen, the clovey gingerbread-like cookies for which the town is famed (not really gingerbread, which is sweetened with honey; these are sweetened with sugar). So on balance I probably got fatter in Aachen.

But at least no one peed neon at me.

Next post: I finish my German-language reading tour in Switzerland and actually take a vacation for the first time in two years, bumping into someone who used to play football for Roman Abramovic… Next post after that: I field emails from people telling me that reading tours sound much like vacations, so I oughtn’t to complain that it’s been two years since I had a formal break….

Affable and trim

The last couple of articles about me and my books focus on the fact that I'm rather happy. In this month's Hadassah Magazine, I'm "affable and trim." High school friends reading this on Facebook may wonder where the affability was back then...

Profile: Hadassah Magazine October 2009 Matt Beynon Rees By Leora Eren Frucht

Only gritty, dark crime fiction could evoke the corruption—and hope—in Palestinian society, believes one former foreign correspondent, now a best-selling mystery writer.

The morning sun streams through the windows that frame the Mount of Olives to the east and the hills of Bethlehem to the south. Photographs of a smiling mother and baby flash, one after the other, on a computer screen. The only sign of anything sinister in this cheerful room is the stainless-steel dagger lying in its open, velvet-trimmed case on the desk.

It is here, in this modest fifth-floor apartment in the southern Jerusalem neighborhood of San Simon, that plans for diabolical schemes of extortion, brutal torture and gruesome murders have been concocted.

With a swift motion, a tall, fair-skinned man grabs hold of the dagger. His piercing pale blue eyes sparkle with anticipation as he turns the shiny weapon slowly in his hands.

“It really is amazing,” he says with a satisfied grin, then adds, in a faint Welsh accent, “I never imagined that it would all go so well.”

Meet Matt Beynon Rees, winner of the The Crime Writers’ Association John Creasey New Blood Dagger and creator of Omar Yussef, literature’s first (and only) Palestinian detective.

Rees, a Welsh-born journalist, won the prestigious British award—an actual dagger, granted to a first-time crime novelist—for his 2007 The Collaborator of Bethlehem (Mariner), in which Yussef makes his debut.

Since then, the affable and trim Rees has cast the stocky, ex-alcoholic Yussef as the star of two more detective novels set in Gaza and Nablus respectively (A Grave in Gaza, Mariner; and The Samaritan’s Secret, Soho Press), with another—The Fourth Assassin—due out in February. The books have been published in 22 countries, earning lavish praise from critics; French daily L’Express dubbed Rees “The Dashiell Hammett of Palestine.”

The novels are more than just well-crafted whodunits. Rees uses Yussef to shine a light on Palestinian society, exposing the traditions, tensions and ties that determine how people act. The reader is led through the squalid refugee camps of Gaza, opulent palaces of corrupt Palestinian power brokers and the alleyways of Nablus’s casbah, which fill with the aroma of knafeh pastry and cardamom by day and empty out at night, when only gunmen prowl its premises. Rees paints a raw, revealing and, at times, alarming portrait of Palestinian society.

“We all think we know Palestinians, whichever stereotype we choose to ascribe to them—victims or terrorists. I want to show that we don’t know them at all,” says Rees, 42. He is sipping an espresso in the study of the apartment he shares with his American-born wife, Devorah Blachor (currently working on her first mystery novel), and their 2-year-old son, Cai (the name means “rejoice” in Welsh).

Rees grew up in a nonreligious Protestant home in Cardiff, South Wales, and says he never imagined he would end up in Jerusalem, let alone become an award-winning mystery writer and documenter of Palestinian reality. The only connection he had to the region are two great-uncles, both coal miners, who fought in General Edmund Allenby’s Imperial Camel Corps, which arrived in Jerusalem in 1917. “Both were injured,” he says. “One had his finger bitten off by a Turk. The other, whom I recall from my childhood, used to get drunk on Christmas, drop his pants and show us the scar where he got shot, in Betunia, which was near Ramallah. You could say my fascination with the region began there,” quips Rees. He pays homage to them in his second book, in which a British war cemetery in Gaza features prominently.

Like his camel-cavorting ancestors, Rees landed in Israel by chance. After studying English language and literature at Oxford, he completed a degree in journalism at the University of Maryland and covered Wall Street for five years, a period he recalls with little enthusiasm. When his American fiancée got posted as a foreign correspondent in Jerusalem, Rees joined her. The two married and subsequently divorced, with Rees remarrying a few years later. But his path was set. He, too, began working as a Jerusalem-based foreign correspondent, first for The Scotsman, then for Newsweek; in 2000, he became Middle East bureau chief for Time magazine.

If Wall Street had dulled his senses, covering the Palestinian beat heightened them: “I felt so alive, everything was so exotic to me—the sights, the sounds. I love the dirt and the dust and the way people speak to each other.”

Rees soon realized that much of what intrigued him about Palestinian society was beyond the scope of traditional journalism. But, he says, “If it didn’t mention the peace process, it wasn’t of interest to my editors.

“Most journalists are really political scientists: They want to write about the peace process and interview the prime minister,” he continues. “I don’t really care about that. I’ve always felt more like an anthropologist. I’m more interested in how people live their lives, what they eat, how their culture shapes them.” To that end, Rees learned basic Hebrew and Arabic.

“Matt has an old-fashioned reporter’s empathy that enables readers to know what his subjects are thinking—without the sheen of postmodern cynicism that characterizes so many foreign correspondents,” says Matthew Kalman, a Jerusalem-based freelance foreign correspondent who has worked with Rees. “[He:] realized early on that reporting the Palestinian-Israeli conflict is extremely superficial…. Most of the foreign media is only interested in a cowboys and Indians story.”

In 2004, Rees published a highly acclaimed nonfiction account of Israeli and Palestinian society entitled Cain’s Field: Faith, Fratricide, and Fear in the Middle East (Free Press), but felt that his effort was not adequate. “I think people want to read about the Middle East, but not in a starchy, nonfiction tone,” he notes.

Rees decided to try his hand at a novel. The Collaborator of Bethlehem was inspired by a specific incident: the cold-blooded killing of one Palestinian by another, a militia man, who accused his victim of collaborating with Israel—knowing full well that the man was innocent.

“The dirtiness of the story made me think it’s so complex that only in a novel can you get those shades of gray, in terms of people’s motivations,” says Rees, who had been dabbling in fiction since childhood. “And it had to be a crime novel because it’s a real gangster reality—not a place for a romance novel.” So, in 2006, after selling the rights to the book, Rees quit Time to write fiction full-time.

Fiction, that is, to a point. The mystery series is based, in part, on actual events and people, including Yussef, a 56-year-old history teacher at a United Nations-administered girls’ school in the Dehaisha refugee camp south of Bethlehem. The pudgy, often breathless grandfather (whose favorite granddaughter builds him a Web site for The Palestine Agency for Detection) is no suave sleuth, but a kind of accidental hero. Driven by a deep sense of integrity, he seeks the truth and tries to fight growing corruption and violence in the West Bank and Gaza Strip—often at considerable personal risk.

“Yussef is based on a friend who lives in Dehaisha refugee camp whom I have known for over 10 years,” says Rees. “He is very much like the character in the book—quite acerbic and very intelligent. He gets very frustrated seeing how corruption and criminality are destroying a society that he loves very much.”

Are there many Omar Yussefs in Palestinian society?

“There are many who have the same basic discontents about the corruption and violence,” he says, “but there are not that many who take action because most feel trapped.” In a telling example of this, in one novel, a man who protests the use of his rooftop to shoot at Israelis meets an untimely fate. “But there are Palestinians who are trying to change things in very small ways,” Rees continues, adding a note of optimism: “I made Omar a teacher because he represents the possibility that the next generation will be different.”

Jamil Hamad, Time’s veteran Palestinian correspondent, says that several Palestinians have shared with him their respect for Rees’s depiction of their society. “I have received calls from other Palestinians here,” Hamad says, “and from Arabs in Jordan, Syria, Egypt and North Africa who say they are very grateful to him for painting a realistic portrait of Palestinians and are proud of the books.”

Yussef’s adversaries—ruthless heads of militias and security forces, weapons smugglers and crooked politicians—make for a colorful cast of bad guys based on real people whom Rees got to know while researching his novels and during his journalistic days. Military Intelligence Chief General Husseini, a character in A Grave in Gaza, is renowned for his particular method of torture: slicing off the tips of prisoners’ fingers. The person and method are real, though the name given to the style of torture—a Husseini manicure—is Rees’s invention.

In researching the novels, Rees spent entire days and nights hanging out with gunmen, most of whom have since been killed—either by Israeli forces or by other Palestinians. Nearly all of them lived with the knowledge that a violent death was imminent.

“It is almost as though they are ghosts when they are alive,” he says. “It feels eerie to have met someone who was as good as dead anyway.”

And because his sinister types are based on portraits of real individuals, he believes that he is able to present complex, nuanced antagonists, rather than cartoon “bad guys.”

“I feel like if you’re a writer and you can ‘know the minds of many men,’ you can tell their story as though it was emerging from your own emotions,” explains Rees, quoting The Odyssey.

“When I was in a refugee camp in the middle of the night, talking to people from Hamas and Fatah who expected to die at any moment, I think I got some insight into the minds of many men,” concludes Rees, whose neutral foreign looks and identity helped him gain access to his subjects and win their trust.

“I think through these novels he is reporting the conflict in a different and exceptional way,” says Hamad. “He’s not just writing a novel—he’s reporting the story. Matt is one of the few journalists I work with who is always capable of ‘digesting’ it properly, meaning he has no illusions.”

Rees’s literary heroes are the classic detective writers Raymond Chandler and Dashiell Hammett. “I love the gritty realism, but I also love the way in which Chandler writes,” he says. “I think he is the greatest stylist of American literature.”

That gritty realism is a hallmark of the Omar Yussef series, which is littered with corpses but also boasts more subtle touches like a swarm of flies that follows the protagonist throughout his sojourn through the filth—both material and moral—of Gaza.

Rees’s own life is a sharp contrast from that of his characters. Every morning, he does a few yoga stretches and writes standing up for several hours at his raised computer terminal. He swims, works out, does Pilates and meditation. He also plays bass in a local band and delights in his toddler son. “I feel younger all the time,” he says happily. He is currently learning piano as part of the research for his new historical novel that evolves around the musical scene in 19th-century Vienna. “I needed a short break from Omar Yussef to refresh myself,” he says.

In The Fourth Assassin (Soho Press), Rees set the action in Bay Ridge, Brooklyn, an area with a growing expatriate Palestinian community, to help American readers “understand the reality of the Muslim minorities living among them.”

A fifth novel will probably unfold in the Old City of Jerusalem and will be the first to include Israeli characters. Rees purposely kept Israelis out of the previous books in which the numerous instances of kidnapping, extortion and murder are almost all committed by Palestinians against other Palestinians. “Part of my goal is to show it is not enough for the Palestinians to say ‘We’re the victims,’” he says. “Palestinians have to take some responsibility. That is what Omar Yussef stands for. When the police won’t solve a murder, Yussef feels he has to do it.”

How long can the series go on? “As long as the publishers want more,” he says, smiling hopefully. “I would like to take Omar throughout the Arab world.

“It’s not difficult to come up with the stories,” he continues. “Palestinians keep giving me material by killing each other and by moving from one disaster to another,” he adds, sounding much like his ever-acerbic but still optimistic Omar Yussef.

Profile: Hadassah Magazine October 2009 Matt Beynon Rees By Leora Eren Frucht

Only gritty, dark crime fiction could evoke the corruption—and hope—in Palestinian society, believes one former foreign correspondent, now a best-selling mystery writer.

The morning sun streams through the windows that frame the Mount of Olives to the east and the hills of Bethlehem to the south. Photographs of a smiling mother and baby flash, one after the other, on a computer screen. The only sign of anything sinister in this cheerful room is the stainless-steel dagger lying in its open, velvet-trimmed case on the desk.

It is here, in this modest fifth-floor apartment in the southern Jerusalem neighborhood of San Simon, that plans for diabolical schemes of extortion, brutal torture and gruesome murders have been concocted.

With a swift motion, a tall, fair-skinned man grabs hold of the dagger. His piercing pale blue eyes sparkle with anticipation as he turns the shiny weapon slowly in his hands.

“It really is amazing,” he says with a satisfied grin, then adds, in a faint Welsh accent, “I never imagined that it would all go so well.”

Meet Matt Beynon Rees, winner of the The Crime Writers’ Association John Creasey New Blood Dagger and creator of Omar Yussef, literature’s first (and only) Palestinian detective.

Rees, a Welsh-born journalist, won the prestigious British award—an actual dagger, granted to a first-time crime novelist—for his 2007 The Collaborator of Bethlehem (Mariner), in which Yussef makes his debut.

Since then, the affable and trim Rees has cast the stocky, ex-alcoholic Yussef as the star of two more detective novels set in Gaza and Nablus respectively (A Grave in Gaza, Mariner; and The Samaritan’s Secret, Soho Press), with another—The Fourth Assassin—due out in February. The books have been published in 22 countries, earning lavish praise from critics; French daily L’Express dubbed Rees “The Dashiell Hammett of Palestine.”

The novels are more than just well-crafted whodunits. Rees uses Yussef to shine a light on Palestinian society, exposing the traditions, tensions and ties that determine how people act. The reader is led through the squalid refugee camps of Gaza, opulent palaces of corrupt Palestinian power brokers and the alleyways of Nablus’s casbah, which fill with the aroma of knafeh pastry and cardamom by day and empty out at night, when only gunmen prowl its premises. Rees paints a raw, revealing and, at times, alarming portrait of Palestinian society.

“We all think we know Palestinians, whichever stereotype we choose to ascribe to them—victims or terrorists. I want to show that we don’t know them at all,” says Rees, 42. He is sipping an espresso in the study of the apartment he shares with his American-born wife, Devorah Blachor (currently working on her first mystery novel), and their 2-year-old son, Cai (the name means “rejoice” in Welsh).

Rees grew up in a nonreligious Protestant home in Cardiff, South Wales, and says he never imagined he would end up in Jerusalem, let alone become an award-winning mystery writer and documenter of Palestinian reality. The only connection he had to the region are two great-uncles, both coal miners, who fought in General Edmund Allenby’s Imperial Camel Corps, which arrived in Jerusalem in 1917. “Both were injured,” he says. “One had his finger bitten off by a Turk. The other, whom I recall from my childhood, used to get drunk on Christmas, drop his pants and show us the scar where he got shot, in Betunia, which was near Ramallah. You could say my fascination with the region began there,” quips Rees. He pays homage to them in his second book, in which a British war cemetery in Gaza features prominently.

Like his camel-cavorting ancestors, Rees landed in Israel by chance. After studying English language and literature at Oxford, he completed a degree in journalism at the University of Maryland and covered Wall Street for five years, a period he recalls with little enthusiasm. When his American fiancée got posted as a foreign correspondent in Jerusalem, Rees joined her. The two married and subsequently divorced, with Rees remarrying a few years later. But his path was set. He, too, began working as a Jerusalem-based foreign correspondent, first for The Scotsman, then for Newsweek; in 2000, he became Middle East bureau chief for Time magazine.

If Wall Street had dulled his senses, covering the Palestinian beat heightened them: “I felt so alive, everything was so exotic to me—the sights, the sounds. I love the dirt and the dust and the way people speak to each other.”

Rees soon realized that much of what intrigued him about Palestinian society was beyond the scope of traditional journalism. But, he says, “If it didn’t mention the peace process, it wasn’t of interest to my editors.

“Most journalists are really political scientists: They want to write about the peace process and interview the prime minister,” he continues. “I don’t really care about that. I’ve always felt more like an anthropologist. I’m more interested in how people live their lives, what they eat, how their culture shapes them.” To that end, Rees learned basic Hebrew and Arabic.

“Matt has an old-fashioned reporter’s empathy that enables readers to know what his subjects are thinking—without the sheen of postmodern cynicism that characterizes so many foreign correspondents,” says Matthew Kalman, a Jerusalem-based freelance foreign correspondent who has worked with Rees. “[He:] realized early on that reporting the Palestinian-Israeli conflict is extremely superficial…. Most of the foreign media is only interested in a cowboys and Indians story.”

In 2004, Rees published a highly acclaimed nonfiction account of Israeli and Palestinian society entitled Cain’s Field: Faith, Fratricide, and Fear in the Middle East (Free Press), but felt that his effort was not adequate. “I think people want to read about the Middle East, but not in a starchy, nonfiction tone,” he notes.

Rees decided to try his hand at a novel. The Collaborator of Bethlehem was inspired by a specific incident: the cold-blooded killing of one Palestinian by another, a militia man, who accused his victim of collaborating with Israel—knowing full well that the man was innocent.

“The dirtiness of the story made me think it’s so complex that only in a novel can you get those shades of gray, in terms of people’s motivations,” says Rees, who had been dabbling in fiction since childhood. “And it had to be a crime novel because it’s a real gangster reality—not a place for a romance novel.” So, in 2006, after selling the rights to the book, Rees quit Time to write fiction full-time.

Fiction, that is, to a point. The mystery series is based, in part, on actual events and people, including Yussef, a 56-year-old history teacher at a United Nations-administered girls’ school in the Dehaisha refugee camp south of Bethlehem. The pudgy, often breathless grandfather (whose favorite granddaughter builds him a Web site for The Palestine Agency for Detection) is no suave sleuth, but a kind of accidental hero. Driven by a deep sense of integrity, he seeks the truth and tries to fight growing corruption and violence in the West Bank and Gaza Strip—often at considerable personal risk.

“Yussef is based on a friend who lives in Dehaisha refugee camp whom I have known for over 10 years,” says Rees. “He is very much like the character in the book—quite acerbic and very intelligent. He gets very frustrated seeing how corruption and criminality are destroying a society that he loves very much.”

Are there many Omar Yussefs in Palestinian society?

“There are many who have the same basic discontents about the corruption and violence,” he says, “but there are not that many who take action because most feel trapped.” In a telling example of this, in one novel, a man who protests the use of his rooftop to shoot at Israelis meets an untimely fate. “But there are Palestinians who are trying to change things in very small ways,” Rees continues, adding a note of optimism: “I made Omar a teacher because he represents the possibility that the next generation will be different.”

Jamil Hamad, Time’s veteran Palestinian correspondent, says that several Palestinians have shared with him their respect for Rees’s depiction of their society. “I have received calls from other Palestinians here,” Hamad says, “and from Arabs in Jordan, Syria, Egypt and North Africa who say they are very grateful to him for painting a realistic portrait of Palestinians and are proud of the books.”

Yussef’s adversaries—ruthless heads of militias and security forces, weapons smugglers and crooked politicians—make for a colorful cast of bad guys based on real people whom Rees got to know while researching his novels and during his journalistic days. Military Intelligence Chief General Husseini, a character in A Grave in Gaza, is renowned for his particular method of torture: slicing off the tips of prisoners’ fingers. The person and method are real, though the name given to the style of torture—a Husseini manicure—is Rees’s invention.

In researching the novels, Rees spent entire days and nights hanging out with gunmen, most of whom have since been killed—either by Israeli forces or by other Palestinians. Nearly all of them lived with the knowledge that a violent death was imminent.

“It is almost as though they are ghosts when they are alive,” he says. “It feels eerie to have met someone who was as good as dead anyway.”

And because his sinister types are based on portraits of real individuals, he believes that he is able to present complex, nuanced antagonists, rather than cartoon “bad guys.”

“I feel like if you’re a writer and you can ‘know the minds of many men,’ you can tell their story as though it was emerging from your own emotions,” explains Rees, quoting The Odyssey.

“When I was in a refugee camp in the middle of the night, talking to people from Hamas and Fatah who expected to die at any moment, I think I got some insight into the minds of many men,” concludes Rees, whose neutral foreign looks and identity helped him gain access to his subjects and win their trust.

“I think through these novels he is reporting the conflict in a different and exceptional way,” says Hamad. “He’s not just writing a novel—he’s reporting the story. Matt is one of the few journalists I work with who is always capable of ‘digesting’ it properly, meaning he has no illusions.”

Rees’s literary heroes are the classic detective writers Raymond Chandler and Dashiell Hammett. “I love the gritty realism, but I also love the way in which Chandler writes,” he says. “I think he is the greatest stylist of American literature.”

That gritty realism is a hallmark of the Omar Yussef series, which is littered with corpses but also boasts more subtle touches like a swarm of flies that follows the protagonist throughout his sojourn through the filth—both material and moral—of Gaza.

Rees’s own life is a sharp contrast from that of his characters. Every morning, he does a few yoga stretches and writes standing up for several hours at his raised computer terminal. He swims, works out, does Pilates and meditation. He also plays bass in a local band and delights in his toddler son. “I feel younger all the time,” he says happily. He is currently learning piano as part of the research for his new historical novel that evolves around the musical scene in 19th-century Vienna. “I needed a short break from Omar Yussef to refresh myself,” he says.

In The Fourth Assassin (Soho Press), Rees set the action in Bay Ridge, Brooklyn, an area with a growing expatriate Palestinian community, to help American readers “understand the reality of the Muslim minorities living among them.”

A fifth novel will probably unfold in the Old City of Jerusalem and will be the first to include Israeli characters. Rees purposely kept Israelis out of the previous books in which the numerous instances of kidnapping, extortion and murder are almost all committed by Palestinians against other Palestinians. “Part of my goal is to show it is not enough for the Palestinians to say ‘We’re the victims,’” he says. “Palestinians have to take some responsibility. That is what Omar Yussef stands for. When the police won’t solve a murder, Yussef feels he has to do it.”

How long can the series go on? “As long as the publishers want more,” he says, smiling hopefully. “I would like to take Omar throughout the Arab world.

“It’s not difficult to come up with the stories,” he continues. “Palestinians keep giving me material by killing each other and by moving from one disaster to another,” he adds, sounding much like his ever-acerbic but still optimistic Omar Yussef.

PW stars new Omar Yussef novel

Publishers Weekly, the pre-publication review, stars my new Palestinian crime novel THE FOURTH ASSASSIN, which will be published Feb. 1 in the US and the UK. Here's the PW review: "The relentless cycle of violence and retribution follows Palestinian detective Omar Yussef to New York City, where he must deliver a speech at the U.N. on schooling in the Palestinian refugee camps, in Rees's excellent fourth mystery (after 2009's "The Samaritan's Secret"). When Yussef's son, Ala, is arrested after a decapitated body is found in Ala's Brooklyn apartment, Yussef's search for the real killer leads him from Atlantic Avenue to Coney Island and back to the U.N. Secretariat. In the process, he discovers that he's not quite the cosmopolitan man he thought himself to be, a realization shared by many Arab immigrants in the story. In truth, the residents of Little Palestine are caught between its subterranean mosques and the lure of Manhattan, where forbidden pleasures are ready for the plucking. Yussef remains reliably human and compassionate toward human fallibility, while raging openly at the corruption of his own leaders."

My Manchurian Candidate

One of my biggest boosters has been Bill Ott, reviewer for the pre-publication review Booklist. Here's his review of my forthcoming THE FOURTH ASSASSIN, which is out in the US and the UK on Feb. 1:

"Road-trips in crime series have the built-in problem of removing their heroes from the landscapes that define them. Rees’ Bethlehem history teacher and occasional sleuth Omar Yussef is a strong enough character to survive a temporary transplant to New York, but that’s not to say we don’t miss the vividly evoked Palestine setting. Yussef has agreed to attend a UN conference in Manhattan because it will give him a chance to see his son Ala who is living in Brooklyn’s Little Palestine neighborhood. The reunion is spoiled, however, when Yussef finds one of Ala’s roommates dead, the victim of what appears to be a ritual killing. With Ala a suspect, Yussef attempts to find the killer. Could the history lessons that Yussef once taught Ala and his friends have been corrupted into a contemporary suicide-assassination plot? Although the setting and the high-concept thriller plot—the finale evokes The Manchurian Candidate—take us too far away from the small human dramas that usually drive this series, Yussef himself never loses sight of what he calls the life that remains when politics is sluiced away like the filth a stray dog leaves in the street."

I like what Bill sees in the novel--and its predecessors--because I've tried to make Omar Yussef a detective who confronts small aspects of the violence around him, rather than writing the kind of thriller where one guy saves the world. That wouldn't reflect the Palestinian reality.

I moved a little further from that smallness of conflict and locality with this new book. Here's why: while a "road trip" can detract from some detectives, it's in the nature of the Palestinian reality to be taken far from home. Most Palestinians, after all, live outside "Palestine." Omar Yussef is lonely and alien in New York, outside his usual milieu. Encapsulating that diaspora is one of the things about which I'm most pleased when it comes to THE FOURTH ASSASSIN.