Matt Rees's Blog - Posts Tagged "renaissance"

My Caravaggio novel 'superb tale of intrigue and wrong doing'

My novel about the great Italian artist Caravaggio A Name in Blood won't be out in the UK until July 1. Still the review copies are out there and the It's a Crime blog gets in first with a very positive mention.

My novel about the great Italian artist Caravaggio A Name in Blood won't be out in the UK until July 1. Still the review copies are out there and the It's a Crime blog gets in first with a very positive mention. A Name in Blood is a superb tale of intrigue and wrong doing in Renaissance Italy from Matt Rees, author of the award winning Omar Yussef crime series.

There's also love and art in the novel. But I'm happy for a crime blog to pick up on the intrigue and wrong doing!

Published on May 09, 2012 02:59

•

Tags:

caravaggio, crime-fiction, historical-fiction, renaissance, reviews

Me and St. Catherine: Why I Wrote a Novel About Caravaggio

On the upper floor of the Museo Thyssen-Bornemisza in central Madrid, I wandered into a broad room where the masterpieces were arrayed like chocolates in a box. Just as with an assortment of sweets, I knew immediately and innately which one attracted me. I stepped into the arms of Caravaggio’s Saint Catherine of Alexandria. She still hasn’t let go.

On the upper floor of the Museo Thyssen-Bornemisza in central Madrid, I wandered into a broad room where the masterpieces were arrayed like chocolates in a box. Just as with an assortment of sweets, I knew immediately and innately which one attracted me. I stepped into the arms of Caravaggio’s Saint Catherine of Alexandria. She still hasn’t let go.I was in Madrid on a book tour for the Spanish translation of the first of my Palestinian crime novels. The Thyssen is just across the wide, busy Paseo del Prado from the immense museum of that name. It’s a building with two wings: a traditional classical palace in burnt sienna and pink stone; alongside a block of bright white louvered walls and angled blue-glass rooflights, like an old auto factory transported to a sci-fi future. I had no idea what awaited me inside. No idea that my novel A NAME IN BLOOD, which is published in the UK in a few weeks, would grow out of it.

The Caravaggio works I had previously seen in London and New York had impressed me. I was aware of the conventional summary of the stylistic revolution he wrought: to fill his canvasses with darkness and, with a strategically placed lantern, to bring the central action shining out of the shadows. That technique has been a major influence on filmmakers like Scorsese and almost every professional photographer, which is why Caravaggio’s four-hundred-year-old paintings look so modern. I knew something about his life too, though largely through the weird distortions and art-house tedium of Derek Jarman, having seen the British director’s Caravaggio film in college. As a writer, however, I’ve found a confluence of impressionability and idea lies behind every novel, so that only at one given time can you write a particular novel. A few years previously, I might’ve seen Saint Catherine, considered her for a moment, then moved on, as I had done when I saw Caravaggio’s The Supper at Emmaus in London’s National Gallery. But, for some reason, when I entered her room at the Thyssen and she spoke to me, I was listening.

I stayed in that room a long time. I couldn’t say quite how long. But it was at least an hour. The other paintings held my attention a matter of moments. I can’t remember them. (I’ve had similar experiences when I’ve traveled to see Caravaggio’s art around the world since then. No artist has such a capacity to make everything else in a gallery ignorable as Caravaggio has). In the Thyssen, I recall that the walls were of a beige rough fabric, a little like delicate sackcloth. The ceiling was white. Details as scant as you might retain from love-making. You might forget your mood or the immediate surroundings, but you’d have a clear picture of the way she looked at you or the feel of her hand on the back of your neck. Of Catherine, I remember everything. Even things that weren’t on the canvas.

The eyes of Caravaggio’s saint were possessive, grasping and sensual, clandestine and forbidden. For much of the time I was with her, we were alone. It felt as intimate as the languor after an act of love. There’s a question in that post-coital moment and Catherine asked it of me: Is this the last time? Will I see you again? Do you want to know more about me and where I come from?

Eventually I tried to leave the empty room. In her face I saw a plea. As if she wanted me to know that by leaving I would abandon her to her fate, represented by the spiked wheel on which she leaned (where the saint was tortured, before she was dispatched with the sword whose shaft she fondles.) What’s so compelling (and in his day was controversial) about Caravaggio is that he didn’t expect the saint’s suffering to be enough to keep you on her side. He gave her the sexual magnetism of Fillide Melandroni, the whore he used as his model.

The hold Caravaggio subsequently took on me amounted to what many people would call an obsession. I prefer not to use that term, because it implies a degree of madness and the inability to see when you’re mistaken about something. A writer needs to know when he’s gone wrong. Still, I traveled all over Europe and America to see Caravaggio’s works. I learned to paint with oils, to fight with a rapier. I grew a beard like the one Caravaggio sported just before his death at age 39. I did a few others things that paralleled the artist’s life and which were too intimate, shameful, or mystical to be recounted here. So, go ahead, call it an obsession.

Published on June 05, 2012 02:23

•

Tags:

baroque, caravaggio, historical-crime, historical-novel, renaissance

Caravaggio's Death Still a Mystery

In July 1610, Michelangelo Merisi, who is known as Caravaggio, was the most famous and controversial artist in Italy. He had killed a man in a duel and was on the run from a powerful Knight of Malta whom the latest research suggests he had injured in a brawl. Then he disappeared.

In July 1610, Michelangelo Merisi, who is known as Caravaggio, was the most famous and controversial artist in Italy. He had killed a man in a duel and was on the run from a powerful Knight of Malta whom the latest research suggests he had injured in a brawl. Then he disappeared.Most art historians have long accepted a strange and unlikely explanation for Caravaggio’s death. Caravaggio left Naples for Rome where he expected to be pardoned for the homicide in the duel and to re-enter the good graces of the Papal nephew, Cardinal Scipione Borghese. But when he disembarked near Rome, Caravaggio was arrested – either through treachery or mistaken identity – and his baggage sailed away with the paintings he had completed to buy his pardon. By the time he was released, he was crazed with rage, frustration and fear. He chased off after the boat up a hundred or so miles of malaria coastline, took fever, and died.

The best one can say about that is: Maybe. As a crime novelist, naturally, I like to think: Maybe not.

My long road of research for my Caravaggio novel A Name in Blood began with Peter Robb’s fabulous biography “M: The Man Who Became Caravaggio.” An Australian who lived a long time in southern Italy, Robb’s account of Caravaggio’s life is detailed in a non-academic way and deeply felt. He examines the mystery surrounding Caravaggio’s disappearance without prejudice, which earned Robb quite a deal of criticism from Caravaggio “scholars” when he published his book in 1998. Academics tend to assume that considering anything other than the hashed-over version of Caravaggio’s death represents a foray into sensationalism, rather than simple curiosity about how this most dynamic of Italian artists simply vanished.

(I encountered a similar preference for the boring and quotidian in professors writing about Mozart’s death, while I researched the composer’s mysterious end for my novel Mozart’s Last Aria. Somehow academics seem committed to taking history’s dramatic events and making them appear as banal as another day in the faculty canteen, and they get inordinately angry with someone like me who decides to eat lunch off campus.)

Vincenzo Pacelli, a University of Naples professor, is the only academic to have asserted (in an 2012 book) that Caravaggio was murdered. He’s often given the brush off, damned with faint praise, by other art historians.

Not long ago an Italian documentarian with a reputation for sensationalism claimed to have found DNA proof that Caravaggio was buried in Porto Ercole, the Tuscan town where conventional wisdom always claimed he died. That was trumpeted as the kind of astounding material the documentarian always unearthed. Whereas, in fact, it’s hardly sensational to have proven the theory of four hundred years correct.

In fact, the documentarian hadn’t proven anything. He had found the bones to have a DNA link to a few people in the town of Caravaggio believed to be related to the artist. But that kind of DNA test can prove that I’m related to a chimpanzee. Because I am, in DNA terms.

Even if Caravaggio was buried at Porto Ercole, the glee of the conventionalists in the debate over the artist’s death was false. If he was buried there, they argued, their theory was correct. Not so. If he was buried in Porto Ercole, it proves only that Caravaggio died. Somewhere. And his body ended up in Porto Ercole. How he died remains a question.

A question that a novel can resolve perhaps as well as an academic article. As a novelist I approached the question by looking at historical research--but also by delving into areas closed to academics: the emotions of the real historical characters in the novel, and my theory of why Caravaggio was so eager to return to Rome. I believe it wasn’t only for the sake of artistic prominence in the Eternal City.

Of course, to find out what I think was driving him, you’ll have to read A Name in Blood.

Published on June 08, 2012 01:23

•

Tags:

art-history, caravaggio, crime-fiction, historical-crime, historical-fiction, italy, renaissance

Meeting Caravaggio at the Cafe: Mystical Research for my Novel

In a Jerusalem café, I was drinking an espresso with Stephen Victor, an Oregon-based practitioner of a process called “family constellations.” I mentioned to him that I thought the process might be useful in my research for A Name in Blood, my historical novel about Caravaggio. Stephen agreed. Though the most common use of constellations is to resolve a family trauma that may even have occurred generations ago and been passed down to those living today, Stephen suggested that if I wanted to connect with Caravaggio about his life I should “just ask him––he’s out there.”

In a Jerusalem café, I was drinking an espresso with Stephen Victor, an Oregon-based practitioner of a process called “family constellations.” I mentioned to him that I thought the process might be useful in my research for A Name in Blood, my historical novel about Caravaggio. Stephen agreed. Though the most common use of constellations is to resolve a family trauma that may even have occurred generations ago and been passed down to those living today, Stephen suggested that if I wanted to connect with Caravaggio about his life I should “just ask him––he’s out there.”It was only a flash, but in that instant Caravaggio was sitting at Stephen’s right, opposite me. He wasn’t precisely “in a chair” next to Stephen. He was higher up, as if inset in a thought bubble. He was in the Jerusalem café, but he also appeared at the same time to be in a tavern in Rome four hundred years ago. He looked sad and yet comfortable in our presence.

Stephen knew Caravaggio was there too. He shivered violently and then shook it off with a twitch of his neck.

Subsequently I used constellations –– or more precisely I “just asked” Caravaggio and others in his life –– to feel my way deeper into the characterizations of A Name in Blood. Most particularly I found a response from Lena, the young woman who I believe was Caravaggio’s lover and who plays a central role in A Name in Blood.

As Stephen often says, this process is intellectually indefensible. So I don’t try to defend it. It happens to be what I’ve experienced, and when I’ve spoken to other creative artists, to actors and musicians, the most open ones often tell me they’ve had similar experiences or used similar techniques. Several German actors spent a night swapping constellations tales with me a year or so ago. My reading of some elliptical statements by Booker-award-winner Hilary Mantel suggests to me she may employ some similar process to achieve her astonishingly vivid characterizations.

The essence of the technique is to centre oneself in a meditative fashion. To focus one’s energy in one’s stomach, rather than in the head. The head is where we judge ourselves negatively––where we tell ourselves that this is all intellectually indefensible and we shouldn’t bother with it. In family constellations, when I’ve been open enough, I’ve felt the energy of someone else’s grandfather or someone’s fear or disease and allowed it to emerge as part of a healing process for that person. It’s the most remarkably cleansing feeling I’ve ever experienced.

Naturally I’ve heard from some people that this is nonsense. After I mentioned constellations while on a panel at a book fair, one of the other panelists, a very well-known British crime writer, joked: “I’m not channeling anyone. I’m doing all the typing.” A lady in the audience stood up to tell him that she thought his characterizations were very good and, therefore, she suspected he was employing something like the constellations technique without even knowing it.

Of course I’m doing the typing. I’m not channeling anyone or anything. Caravaggio didn’t write A Name in Blood, I did. If I was channeling him, I’d be painting, not writing, believe me.

But if you, like my British crime writer pal, think your head holds all the answers to everything, why does it choose to make life so miserable much of the time. Why does it fear an answer that might originate in some other part of the body?

In the West, there’s a tyranny of the brain, of the intellectually defensible. It’s like any of the other tyrannies we’ve embraced –– patriarchy, capitalism, monotheism. It demonizes any other way of thinking and often does so through mockery. If those systems don’t always work, they can be nipped and tucked, but don’t you even think of looking elsewhere for a better system. That’s the message at the heart of our culture of intellectual defensibility.

Personally I want my novel to be as good as it can be (and for me to be as happy as I can be). I don’t care what apparently silly things I have to do, what processes I must engage in, to get it that way. I know that A Name in Blood has been touched by Caravaggio, even if some might think that sounds daft.

Besides, the Caravaggio I met wasn’t at all the way you’d think from the writings of art historians. Their Caravaggio, as I’ve written elsewhere on this blog, was some kind of gay psycho bitch. But mine was different. I liked him. I hope you will too.

Published on June 14, 2012 02:57

•

Tags:

a-name-in-blood, art, art-history, baroque, caravaggio, crime-fiction, historical-crime, historical-fiction, renaissance, writing

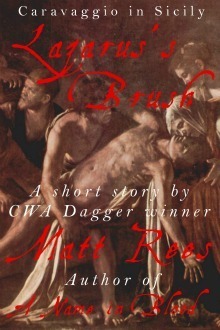

FREE Caravaggio short story download

My historical crime novel about the mysterious end of Caravaggio is out in the UK in a couple of weeks. As a taster for A NAME IN BLOOD, I'm making available a short story "Lazarus's Brush" that's also about the great Italian artist. The download is FREE until Sunday. It includes the short story, plus a sample chapter from the novel and a personal essay about how I came to write A NAME IN BLOOD. (A bit like all the extra stuff you get on a DVD, but without the "commentary" track. Maybe I'll do one of those on my Podcast some time....Well, if you do listen to the Podcast, you can hear me talking about how I wrote A NAME IN BLOOD and reading a chapter already.) In the short story "Lazarus's Brush," Caravaggio flees to Sicily with a price on his head. Commissioned to paint the raising of Lazarus, he learns about his fears of the violence that stalks him. But the story also charts a profound change in his artistic technique. It's an episode I didn't include in the novel, but it's a compelling moment in Caravaggio's life and work nonetheless. Download the US version. Get the UK edition. The Caravaggio painting at the heart of "Lazarus's Brush" has just been restored, by the way. You can read more about the restoration here.

Published on June 20, 2012 00:23

•

Tags:

art, art-history, caravaggio, crime-fiction, free-promotion, free-short-story, historical-fiction, historical-thriller, raising-of-lazarus, renaissance

Writing with Paint: Learning Oils for My Caravaggio Novel 'A Name in Blood'

To research A Name in Blood, my novel about the mystery of Caravaggio’s death, I traveled to all the places where the great artist lived and worked. I visited galleries around the world to stand before his masterpieces, and I read scores of books about him and the period in which he lived. (I don’t expect praise for this; it was no sacrifice, because most of the research was carried out in Italy. It’s a bit like saying, "I had to have sex with a lot of beautiful women to write this book." Except that my wife came with me to do the research, so it only involved one beautiful woman.)

To research A Name in Blood, my novel about the mystery of Caravaggio’s death, I traveled to all the places where the great artist lived and worked. I visited galleries around the world to stand before his masterpieces, and I read scores of books about him and the period in which he lived. (I don’t expect praise for this; it was no sacrifice, because most of the research was carried out in Italy. It’s a bit like saying, "I had to have sex with a lot of beautiful women to write this book." Except that my wife came with me to do the research, so it only involved one beautiful woman.)But none of this would’ve been worth a damn if, when it came to write about Caravaggio at work, I hadn’t had some idea of how to create a painting out of oils.

Trouble was, when I started my research, that was exactly where things stood. In fact, I was pretty sure I couldn’t draw at all.

My brother Dom got the talent with the paint brush in our family, I thought. Inherited from my Dad, who’s an architect and a fine caricaturist. Dom studied fine art and teaches art at a school in London. I was certain that old Mrs. Coneybear, my ludicrously named, Joyce Grenfell-like high school art teacher, had been correct when she glanced over my sketches midway through class and said, “I think you’d better model for the other pupils today, Rees.”

Still, never write anyone off, Mrs. Coneybear. My sister turns out to be rather a good painter, and my mother just made a clay model that looks exactly like the Picasso on which she modeled it. So evidently the whole family has it in them.

Because while I didn’t manage to match Caravaggio (needless to say, that wasn’t my goal), I did find intense pleasure in the concentration and delicacy and even the little tricks needed to paint in oils.

My friend Yael Robin, whose fabulous installations have been shown at the Israel Museum among other fine locations, gave me a few lessons. She emphasized drawing to begin with. I found I wasn’t quite awful, but I knew there was no great talent there.

My friend Yael Robin, whose fabulous installations have been shown at the Israel Museum among other fine locations, gave me a few lessons. She emphasized drawing to begin with. I found I wasn’t quite awful, but I knew there was no great talent there.So we soon moved onto the important stuff. Oils. It transpires that oils are, in may ways, easier than pen and ink, because they’re more forgiving. Draw the wrong line with a pen and it shall remain wrong. Do it with oils and you can scrape it away or smudge it.

In fact, there’s a parallel between oils versus pen and the way I play music. I’ve never been particularly good at playing exactly what’s written on a page of music. I prefer to play in a way that improvises around that musical text. It means I’m not much use at the exactitude of classical music. I don’t much go for the endlessly repeated rock guitar riff either. But I love to diddle around with the notes and make something that’s always new. So too with oils. They’re built up slowly and unless you’re trying to make a photographic representation of something there’s a good deal of leeway with color and line. There’s also time to savor the scent of the linseed oil and turpentine in the room.

That may be why I love Caravaggio’s later works so much. He had moved away from the precision of his earlier pieces. His work reflected his life on the run, but also, I think, the way he felt about life and the soul. Essentially he was painting light, and light often comes at us broken down and inexact.

As you'll see from the examples of my work here (and more I intend to post tomorrow), I made some inexact and broken down (though only in the positive sense of the term!) copies of details from Caravaggio’s works. I’m quite sure A Name in Blood is better for that. I know that I am.

Published on June 25, 2012 04:39

•

Tags:

art, art-history, caravaggio, crime-fiction, historical-fiction, painting, renaissance

Taking My Research TOO Far: Caravaggio and Willy Wonka

As Willy Wonka says in “Charlie and the Great Glass Elevator,” the wisest men know that they need to indulge in some nonsense from time to time. Which is why I like to take my research for my novels just a bit too far.

As Willy Wonka says in “Charlie and the Great Glass Elevator,” the wisest men know that they need to indulge in some nonsense from time to time. Which is why I like to take my research for my novels just a bit too far.For A Name in Blood I did more than just read about the great Italian artist Caravaggio and look at his work. I learned to fence with a sixteenth-century rapier and to paint with oils, for example. A bit beyond the call of duty, but so far so reasonable.

But then I decided to follow Wonka’s advice. So I grew a beard and dyed it black, because that’s how Caravaggio’s beard looked. I cut my hair in his style. I communicated with the spiritual energy of the artist and his lover in a what might be described as a very New Age fashion. I was gripped by fear and panic at night in Malta, as was he, and I got into a little, ahem, trouble in a bar in Naples. He, of course, found trouble everywhere.

The result was twofold. For one thing, it’s a stunningly good novel out in the UK on 5 July. (If I can’t blow my own trumpet, then what’s a blog post for?) But also the extra stages of my research took me so deeply into Caravaggio’s experiences that they changed my own experience of the world.

Caravaggio’s story is usually told as a tale of a brilliant painter whose tendency to violence, leading ultimately to his death at the age of 39, ruined what could otherwise have been a much more productive and happy career. After all my research, I decided the central feature of his life had been something else entirely: Caravaggio was looking for love.

How did I know this? I found it in his paintings. Look at his amazing Madonna with the Serpent and you’ll fall in love, as I did, with Lena, the model for the mother of Jesus. But more than that, behind all the dressing up and role-playing of my research was the sense that Caravaggio’s experience of life had been similar to mine. Not absolutely parallel, because fortunately my father and grandfather didn’t die of bubonic plague when I was six years old as Caravaggio’s did. (There were no recorded outbreaks in Wales in the early 1970s.) But his psychodrama was close enough to mine for me to feel a kinship with him. I’d summarize it thus: like him, I have a deep creative urge that’s rooted in what felt to me, at least, like childhood upheaval; I’ve often been compelled to work for people I despised; our romantic histories are complicated; anger has been… a problem; neither of us lived long in one place; we both found love.

That’s why I didn’t leave my interest in him on the gallery wall. I had to make of him a book, because I believed his story would help me make sense of my own emotions.

Without giving away the story of A Name in Blood, I’ll tell you that Caravaggio’s early paintings show a yearning for love in a man with little control over his life. His middle paintings reflect a sense of the love that he found. The late paintings show a man on the run (under sentence of death) who only then appreciates the depth of his love, both physical and spiritual.

Now that A Name in Blood is about to be published, I don’t have to keep dying my beard. But Caravaggio’s still with me. I hope he’ll soon be with you, too.

Published on June 28, 2012 02:05

•

Tags:

a-name-in-blood, art, art-history, caravaggio, crime-fiction, historical-fiction, renaissance, research