Matt Rees's Blog - Posts Tagged "yasmina-khadra"

Guardian: Top 10 Arab-world novels

"The Arab literary world and Western publishing don't cross over much. The literature of the Arab world is largely unknown in the west, and even westerners who write about Arabs are sometimes seen as fringe, cult writers. That comes at a cost to the west, because literature could be such an important bridge between two cultures so much at odds. What we see of the Arab world comes from news reports of war and other madness. Literature would be a much more profound contact.

"I live in Jerusalem and write fiction about the Palestinians because it's a better way to understand the reality of life in Palestine than journalism and non-fiction. The books in this list, in their different ways, unveil elements of life across the Arab world that you won't see in the newspaper or on TV."

Published on January 13, 2010 23:17

•

Tags:

abdulrahman-munif, ala-al-aswany, algeria, arab, arab-fiction, arab-novels, british-newspapers, cairo, egypt, emile-habiby, ibrahim-nasrallah, iraq, israel, kanaan-makiya, lawrence-durrell, middle-east, naguib-mahfouz, palestine, palestinians, paul-bowles, tariq-ali, the-guardian, yasmina-khadra

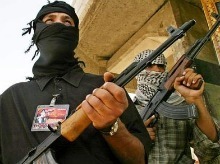

For Arabs: democracy, then crime fiction

Crime fiction may not be the first thing on the minds of the protesters taking to the streets for democracy across the Arab world. But one of the offshoots of the downfall of Arab dictators is sure to be an explosion of thrillers and mysteries.

Crime fiction may not be the first thing on the minds of the protesters taking to the streets for democracy across the Arab world. But one of the offshoots of the downfall of Arab dictators is sure to be an explosion of thrillers and mysteries.Until now there has been almost no crime fiction written in Arabic. A couple of little-known writers in Egypt and Morocco have contributed old-fashioned Agatha Christie-style cosies (“One of the people at this oasis is the killer.”) The best Arab detective writer has been Yasmina Khadra, whose series about Inspector Llob is supremely gory and noirish. But Khadra writes in French from exile in France.

I believe Arabs have eschewed crime writing because it’s a democratic genre. One man wants to find out something that a big organization – the CIA, the mafia, the government – wants to keep secret. It’s easy to see why Hosni Mubarak probably wasn’t a fan of Raymond Chandler.

For people who live in democracies, it’s easy to find fiction credible that suggests a man can investigate – and once he fingers the bad guy, the bad guy will be punished. That’s why Scandinavian crime fiction by Henning Mankell et al is so popular: the Nordic societies have us all convinced that an eruption of violence, crime or murder, will soon enough be resolved and life can go back to its usual extreme orderliness.

Not so for the Arab world. Arabs have a deep sense of fatalism. Not only do they lack faith that the bad guy will be punished, they’re quite sure the bad guy will prosper. He’ll drive his Mercedes to his villa directly from the government offices or state-run companies where he rakes off his big take. The ordinary guy will be left to live on $2 a day.

When I came to write my series of Palestinian crime novels, one of the challenges was to make the format of the crime novel work in an environment where law and order didn’t really function or protect ordinary citizens. I did it by demonstrating that while my sleuth, Omar Yussef, might nail one bad guy at the end of the book, he would be left with an awareness that there were many other guilty men who had escaped him. As one German reader put it to me at a book festival, “I like your books because, in the end, everyone’s guilty.” The reason people across the Arab world are rising up is because they don’t want to share the guilt and shame of their broken, repressed societies any more.

Read the rest of this post on my blog The Man of Twists and Turns.

These observations are true even for countries where there isn’t what we’d call a Western-style democracy – which I’d characterize as a democracy where corruption is either extremely well-hidden or disguised as a stock market in which all can supposedly participate. Take Russia, for example. Clearly not the democracy its people might dream of. But nonetheless one in which opposition journalists – at considerable risk to themselves – do function in the face of the state apparatus and its corrupt overlords.

In South Africa, there was almost no local crime fiction under apartheid. When that changed, there was an explosion of crime writing.

The situation in the Arab world is changing now. Which shows that there’s a thirst for democracy, for accountability – and, therefore, for crime fiction.

Published on February 24, 2011 00:55

•

Tags:

agatha-christie, arabs, crime-fiction, democracy, henning-mankell, hosni-mubarak, middle-east, omar-yussef, raymond-chandler, writing, yasmina-khadra