Matt Rees's Blog - Posts Tagged "agatha-christie"

Overturning detective fiction: everyone's guilty in my novels

The “Golden Age” of the detective story was the 1920s and 1930s. It was a turbulent period. In Britain, the General Strike. In the U.S., the Depression. Civil war in Spain, and in Germany the rise of the Nazis. Red scares everywhere, fascists too.

The “Golden Age” of the detective story was the 1920s and 1930s. It was a turbulent period. In Britain, the General Strike. In the U.S., the Depression. Civil war in Spain, and in Germany the rise of the Nazis. Red scares everywhere, fascists too.But the detective story was a solace to those who lived in such ugly times. In the model employed by Agatha Christie and Dorothy L. Sayers, the story ended with one criminal fingered by the detective. Everyone else turned out to be innocent. Order was restored. It was as if the writers were saying, Don’t worry about what you read in the newspapers; everything can be fixed and only a small minority are making the trouble.

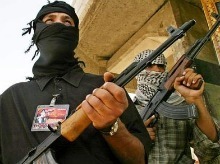

In my Palestinian crime novels, the opposite is true. Everyone’s guilty. Tat’s the reality I found in Palestinian society, as disaster befell it in the last decade – an intifada, a civil war, and now a horrible stand-off between rival factions. Not any one person’s fault.

I believe that’s a better reflection of the world in which we live. My novels are entertainments, but they aren’t layered with the conservative perspective of the “Golden Age.” I don’t want readers to think that there’s nothing wrong out there, so long as the detective nabs the sole bad guy in the library.

Crime novels today are grittier than the work of Christie. They tend to be closer to the atmosphere of Raymond Chandler, who wrote that the Golden Age stories “really get me down.” But the Chandler ethos of a lone knight facing an utterly corrupt world is largely ignored.

That’s why there are so many novels these days about pedophiles and psychopaths. Such characters are beyond the pale of behavior in which we could imagine ourselves participating. To commit a crime in such novels is to mark oneself out as a deviant. As soon as the deviant is nabbed, the society can go back into its usual calm manner.

I think this is why Scandinavian crime novels have been so popular. Readers like the fact that, while the detective wrestles with the psycho, the society depicted is clearly not so very flawed. As soon as the psycho is nabbed, Sweden will return to its pleasant, polite way of life—something that’s easier to envisage than it would be in a novel set in, say, Bangkok or Gaza. Even in his recent novel, “The Worried Man,” Henning Mankell describes his detective as being no more than “worried about the direction of Swedish society.”

Worried! Can you imagine Omar Yussef, my Palestinian sleuth, being no more than worried? He lives in a society that’s engulfed in disaster. He knows everything’s going to hell and he’s aware that nabbing a single bad guy won’t change that.

The golden age method ought to have been overtaken by reality in a post-Holocaust age. Hannah Arendt wrote of the banality of evil, meaning that people don’t choose good or bad, they just go along. We’d like to see bad guys as pure evil, deciding firmly to commit horrible acts, while the truth of the Holocaust and many other dreadful events is that people are much more likely to operate in a kind of malleable denial.

It’s a vital insight. Yet I find most crime novels are written as though Hitler never happened—as if one wicked man can be blamed for what millions of others simply went along with.

Read the rest of this post on my blog The Man of Twists and Turns.

Published on September 09, 2010 02:19

•

Tags:

agatha-christie, crime-fiction, detective-stories, dorothy-l-sayers, hannah-arendt, henning-mankell, hitler, holocaust, intifada, nordic-crime, omar-yussef, palestine, palestinian, raymond-chandler, the-samaritan-s-secret

For Arabs: democracy, then crime fiction

Crime fiction may not be the first thing on the minds of the protesters taking to the streets for democracy across the Arab world. But one of the offshoots of the downfall of Arab dictators is sure to be an explosion of thrillers and mysteries.

Crime fiction may not be the first thing on the minds of the protesters taking to the streets for democracy across the Arab world. But one of the offshoots of the downfall of Arab dictators is sure to be an explosion of thrillers and mysteries.Until now there has been almost no crime fiction written in Arabic. A couple of little-known writers in Egypt and Morocco have contributed old-fashioned Agatha Christie-style cosies (“One of the people at this oasis is the killer.”) The best Arab detective writer has been Yasmina Khadra, whose series about Inspector Llob is supremely gory and noirish. But Khadra writes in French from exile in France.

I believe Arabs have eschewed crime writing because it’s a democratic genre. One man wants to find out something that a big organization – the CIA, the mafia, the government – wants to keep secret. It’s easy to see why Hosni Mubarak probably wasn’t a fan of Raymond Chandler.

For people who live in democracies, it’s easy to find fiction credible that suggests a man can investigate – and once he fingers the bad guy, the bad guy will be punished. That’s why Scandinavian crime fiction by Henning Mankell et al is so popular: the Nordic societies have us all convinced that an eruption of violence, crime or murder, will soon enough be resolved and life can go back to its usual extreme orderliness.

Not so for the Arab world. Arabs have a deep sense of fatalism. Not only do they lack faith that the bad guy will be punished, they’re quite sure the bad guy will prosper. He’ll drive his Mercedes to his villa directly from the government offices or state-run companies where he rakes off his big take. The ordinary guy will be left to live on $2 a day.

When I came to write my series of Palestinian crime novels, one of the challenges was to make the format of the crime novel work in an environment where law and order didn’t really function or protect ordinary citizens. I did it by demonstrating that while my sleuth, Omar Yussef, might nail one bad guy at the end of the book, he would be left with an awareness that there were many other guilty men who had escaped him. As one German reader put it to me at a book festival, “I like your books because, in the end, everyone’s guilty.” The reason people across the Arab world are rising up is because they don’t want to share the guilt and shame of their broken, repressed societies any more.

Read the rest of this post on my blog The Man of Twists and Turns.

These observations are true even for countries where there isn’t what we’d call a Western-style democracy – which I’d characterize as a democracy where corruption is either extremely well-hidden or disguised as a stock market in which all can supposedly participate. Take Russia, for example. Clearly not the democracy its people might dream of. But nonetheless one in which opposition journalists – at considerable risk to themselves – do function in the face of the state apparatus and its corrupt overlords.

In South Africa, there was almost no local crime fiction under apartheid. When that changed, there was an explosion of crime writing.

The situation in the Arab world is changing now. Which shows that there’s a thirst for democracy, for accountability – and, therefore, for crime fiction.

Published on February 24, 2011 00:55

•

Tags:

agatha-christie, arabs, crime-fiction, democracy, henning-mankell, hosni-mubarak, middle-east, omar-yussef, raymond-chandler, writing, yasmina-khadra