Matt Rees's Blog - Posts Tagged "how-to-write"

Podcast: How to Write a Book -- Research

My latest podcast is the first of a three-part series on how to write your book. This episode is about research.

Published on August 01, 2011 03:29

•

Tags:

how-to-write, podcast, research, writers, writing

Podcast: How to Write a Book -- Structure and Plot

In my latest podcast I use my experience as an award-winning writer of nonfiction, crime fiction, and historical thrillers to show how to structure your book and, in the case of fiction, how to lay out your plot. This is the second of three episodes titled How to Write a Book. The next episode will cover writing and editing the book.

Published on August 07, 2011 01:59

•

Tags:

crime-fiction, historical-fiction, how-to-write, nonfiction, podcast, writers-on-writing, writing

Likeable Schmikeable: Jasmine Schwartz’s Writing Life interview

The hottest new voice in crime fiction is Jasmine Schwartz. Her great debut “Farbissen” and its follow-up “Fakakt” have earned plaudits for her and for her detective, neurotic New York fashionista Melissa Morris. The books have been called “Bridget Jones with guns and dead bodies.” But Jasmine’s no Renee Zellweger softie, as you’ll see from her hilarious blog. Personally (to misquote a Zellweger line) she had me at the titles. Farbissen means "embittered" in Yiddish, while Fakakt means "screwed." Both her novels are stylish and very funny, but they also tackle important social issues, like race and sex trafficking. Jasmine chats about the way she writes, and why:

The hottest new voice in crime fiction is Jasmine Schwartz. Her great debut “Farbissen” and its follow-up “Fakakt” have earned plaudits for her and for her detective, neurotic New York fashionista Melissa Morris. The books have been called “Bridget Jones with guns and dead bodies.” But Jasmine’s no Renee Zellweger softie, as you’ll see from her hilarious blog. Personally (to misquote a Zellweger line) she had me at the titles. Farbissen means "embittered" in Yiddish, while Fakakt means "screwed." Both her novels are stylish and very funny, but they also tackle important social issues, like race and sex trafficking. Jasmine chats about the way she writes, and why:Plug your latest book. What’s it about? Why’s it so great?

The book is FARBISSEN: MELISSA MORRIS AND THE MEANING OF MONEY. The novel follows some conventions of a mystery series, while ignoring others completely. It incorporates humor with serious themes, such as depression and racism. As a reader, this is always my favorite kind of writing – when I laugh but also have a deeper, emotional reaction.

The book is FARBISSEN: MELISSA MORRIS AND THE MEANING OF MONEY. The novel follows some conventions of a mystery series, while ignoring others completely. It incorporates humor with serious themes, such as depression and racism. As a reader, this is always my favorite kind of writing – when I laugh but also have a deeper, emotional reaction.How much of what you do is formula dictated by the genre within which you write? Or as close to complete originality as it’s possible to get each time?

Agents and Publishers like to say, about protagonists, "Make them likeable. Every woman should want to be your main character." I always hated that. I love David Sedaris because he can take his deepest flaws, look them in the eye, and make them the centerpiece of his essays. That's who I want to read. Emotional honesty is so much more compelling then a whitewashed character.

What’s your favorite sentence in all literature, and why?

"The story so far: In the beginning the Universe was created. This has made a lot of people very angry and been widely regarded as a bad move." Douglas Adams started The Restaurant at the End of the Universe with that. Why do I love it? Simple. I grew up religious, educated by Rabbis and with an education that begged us not to question the basic concepts of our faith. "In the beginning" is the first sentence of "adult" literature I learned, at age five. But I think Douglas wrote it better.

Who’s the greatest stylist currently writing?

Martin Cruz Smith comes to mind. Larry McMurtry is wonderful. Hilary Mantel's Wolf Hall and A Place of Greater Safety were both phenomenal.

Who’s the greatest plotter currently writing?

Dennis Lehane's Shutter Island was awesome.

Where’d you get the idea for your main character?

I was on the train with my husband. He was considering writing a detective series, and we were brainstorming different sleuths. I said, "How about writing one about a neurotic New Yorker?" Then I realized I should do that one.

Do you have a pain from childhood that compels you to write? If not, what does?

The childhood stuff gets you started writing when you're young, I think. But then, if you continue writing, it's for different reasons. For me, writing brings out my creative energy and taps into my spiritual side. That’s all hard to remember when you confront the commercial aspect of the craft [i.e. selling your work], but it's important to remember this motivation at the core.

What’s the best idea for marketing a book you can do yourself?

My husband is the greatest resource ever for such ideas. I guess that's not doing it myself, but I do feed him.

What’s your weirdest idea for a book you’ll never get to publish?

Aliens on Long Island. Lost tribes and lost souls. Mass face-lifts. It’s sci-fi, baby, sci-fi.

Published on May 23, 2012 09:33

•

Tags:

chick-lit, crime-fiction, how-to-write, women-s-fiction, writers, writing-interviews, writing-life, yiddish

Likeable Schmikeable: Jasmine Schwartz’s Writing Life interview

The hottest new voice in crime fiction is Jasmine Schwartz. Her great debut “Farbissen” and its follow-up “Fakakt” have earned plaudits for her and for her detective, neurotic New York fashionista Melissa Morris. The books have been called “Bridget Jones with guns and dead bodies.” But Jasmine’s no Renee Zellweger softie, as you’ll see from her hilarious blog. Personally (to misquote a Zellweger line) she had me at the titles. Farbissen means "embittered" in Yiddish, while Fakakt means "screwed." Both her novels are stylish and very funny, but they also tackle important social issues, like race and sex trafficking. Jasmine chats about the way she writes, and why:

The hottest new voice in crime fiction is Jasmine Schwartz. Her great debut “Farbissen” and its follow-up “Fakakt” have earned plaudits for her and for her detective, neurotic New York fashionista Melissa Morris. The books have been called “Bridget Jones with guns and dead bodies.” But Jasmine’s no Renee Zellweger softie, as you’ll see from her hilarious blog. Personally (to misquote a Zellweger line) she had me at the titles. Farbissen means "embittered" in Yiddish, while Fakakt means "screwed." Both her novels are stylish and very funny, but they also tackle important social issues, like race and sex trafficking. Jasmine chats about the way she writes, and why:Plug your latest book. What’s it about? Why’s it so great?

The book is FARBISSEN: MELISSA MORRIS AND THE MEANING OF MONEY. The novel follows some conventions of a mystery series, while ignoring others completely. It incorporates humor with serious themes, such as depression and racism. As a reader, this is always my favorite kind of writing – when I laugh but also have a deeper, emotional reaction.

The book is FARBISSEN: MELISSA MORRIS AND THE MEANING OF MONEY. The novel follows some conventions of a mystery series, while ignoring others completely. It incorporates humor with serious themes, such as depression and racism. As a reader, this is always my favorite kind of writing – when I laugh but also have a deeper, emotional reaction.How much of what you do is formula dictated by the genre within which you write? Or as close to complete originality as it’s possible to get each time?

Agents and Publishers like to say, about protagonists, "Make them likeable. Every woman should want to be your main character." I always hated that. I love David Sedaris because he can take his deepest flaws, look them in the eye, and make them the centerpiece of his essays. That's who I want to read. Emotional honesty is so much more compelling then a whitewashed character.

What’s your favorite sentence in all literature, and why?

"The story so far: In the beginning the Universe was created. This has made a lot of people very angry and been widely regarded as a bad move." Douglas Adams started The Restaurant at the End of the Universe with that. Why do I love it? Simple. I grew up religious, educated by Rabbis and with an education that begged us not to question the basic concepts of our faith. "In the beginning" is the first sentence of "adult" literature I learned, at age five. But I think Douglas wrote it better.

Who’s the greatest stylist currently writing?

Martin Cruz Smith comes to mind. Larry McMurtry is wonderful. Hilary Mantel's Wolf Hall and A Place of Greater Safety were both phenomenal.

Who’s the greatest plotter currently writing?

Dennis Lehane's Shutter Island was awesome.

Where’d you get the idea for your main character?

I was on the train with my husband. He was considering writing a detective series, and we were brainstorming different sleuths. I said, "How about writing one about a neurotic New Yorker?" Then I realized I should do that one.

Do you have a pain from childhood that compels you to write? If not, what does?

The childhood stuff gets you started writing when you're young, I think. But then, if you continue writing, it's for different reasons. For me, writing brings out my creative energy and taps into my spiritual side. That’s all hard to remember when you confront the commercial aspect of the craft [i.e. selling your work], but it's important to remember this motivation at the core.

What’s the best idea for marketing a book you can do yourself?

My husband is the greatest resource ever for such ideas. I guess that's not doing it myself, but I do feed him.

What’s your weirdest idea for a book you’ll never get to publish?

Aliens on Long Island. Lost tribes and lost souls. Mass face-lifts. It’s sci-fi, baby, sci-fi.

Published on May 23, 2012 09:33

•

Tags:

chick-lit, crime-fiction, how-to-write, women-s-fiction, writers, writing-interviews, writing-life, yiddish

Write a thriller: How Don Winslow propels a plot around its Midpoint

The key to the pace of a thriller lies in the Midpoint

The Midpoint is a plot point that lies, of course, at the halfway point of the book. What does it do? It propels the hero out of the first part of Act II, where s/he has been encountering new signs of the bad guys and their dirty dealings. It shoots the hero into the breakneck action of the second part of Act II, where the bad guys close in on the hero, trouble piles up on the hero, and it looks as though s/he is going to lose.

The Midpoint is a plot point that lies, of course, at the halfway point of the book. What does it do? It propels the hero out of the first part of Act II, where s/he has been encountering new signs of the bad guys and their dirty dealings. It shoots the hero into the breakneck action of the second part of Act II, where the bad guys close in on the hero, trouble piles up on the hero, and it looks as though s/he is going to lose.

How do you create a good Midpoint? A couple of tips:

Kill someone to add a heightened element of danger and a new impetus for the hero's chase

Introduce a new character whose presence adds to the danger

Change the nature of the threat to the hero dramatically

The king of the threat-change is Don Winslow. Read his fabulous Satori for an example that'll take your breath away.

The king of the threat-change is Don Winslow. Read his fabulous Satori for an example that'll take your breath away.

Without giving too much away, the reader spends the first half of Satori thinking the hero has to do a particular thing, after which he'll be safe. Instead, at the Midpoint of Satori, Winslow delivers a plot-point double punch. The hero accomplishes that particular thing -- at great risk and with much tension. Only to discover immediately that he has been betrayed. For the rest of the book, he faces entirely new risks. The reader experiences the same sudden shift and confusion as the hero. That means, tension. Which is a good thing in a thriller.

The show 24 does this too. Ever noticed how Jack Bauer is fighting one lot of bad guys for the first 12 hours, only to realize half way through the season that the real bad guy is someone completely different with an entirely different plan?

The show 24 does this too. Ever noticed how Jack Bauer is fighting one lot of bad guys for the first 12 hours, only to realize half way through the season that the real bad guy is someone completely different with an entirely different plan?

Works, doesn't it?

Don't forget to get my FREE ebook. It's packed with original, exclusive crime stories.

The Midpoint is a plot point that lies, of course, at the halfway point of the book. What does it do? It propels the hero out of the first part of Act II, where s/he has been encountering new signs of the bad guys and their dirty dealings. It shoots the hero into the breakneck action of the second part of Act II, where the bad guys close in on the hero, trouble piles up on the hero, and it looks as though s/he is going to lose.

The Midpoint is a plot point that lies, of course, at the halfway point of the book. What does it do? It propels the hero out of the first part of Act II, where s/he has been encountering new signs of the bad guys and their dirty dealings. It shoots the hero into the breakneck action of the second part of Act II, where the bad guys close in on the hero, trouble piles up on the hero, and it looks as though s/he is going to lose.How do you create a good Midpoint? A couple of tips:

Kill someone to add a heightened element of danger and a new impetus for the hero's chase

Introduce a new character whose presence adds to the danger

Change the nature of the threat to the hero dramatically

The king of the threat-change is Don Winslow. Read his fabulous Satori for an example that'll take your breath away.

The king of the threat-change is Don Winslow. Read his fabulous Satori for an example that'll take your breath away.Without giving too much away, the reader spends the first half of Satori thinking the hero has to do a particular thing, after which he'll be safe. Instead, at the Midpoint of Satori, Winslow delivers a plot-point double punch. The hero accomplishes that particular thing -- at great risk and with much tension. Only to discover immediately that he has been betrayed. For the rest of the book, he faces entirely new risks. The reader experiences the same sudden shift and confusion as the hero. That means, tension. Which is a good thing in a thriller.

The show 24 does this too. Ever noticed how Jack Bauer is fighting one lot of bad guys for the first 12 hours, only to realize half way through the season that the real bad guy is someone completely different with an entirely different plan?

The show 24 does this too. Ever noticed how Jack Bauer is fighting one lot of bad guys for the first 12 hours, only to realize half way through the season that the real bad guy is someone completely different with an entirely different plan?Works, doesn't it?

Don't forget to get my FREE ebook. It's packed with original, exclusive crime stories.

Published on March 13, 2014 23:46

•

Tags:

24, crime-fiction, don-winslow, how-to-write, jack-bauer, satori, thrillers, write-a-thriller, writing

Write a thriller: Know the plot's destination before you start

Figure out the end of the novel before you start to write

The great thriller writer Joseph Finder told me that figuring out the end of the novel is a key to getting started. “Gotta know the destination,” he said. (More from Joseph on plot.)

The great thriller writer Joseph Finder told me that figuring out the end of the novel is a key to getting started. “Gotta know the destination,” he said. (More from Joseph on plot.)

Take a look at my diagram of the outline for a thriller (You've seen it before). The two pieces I fill in first are the Set Up in Act I and the Payoff in Act III, where the hero prevents whatever the bad guy aims to do.

Why do it that way? Because you gotta know the destination before you start on the journey. If you don’t, you’ll meander. That nice rising diagonal line across the diagram will droop and zig zag -- and that means losing momentum. You’ll waste a lot of energy going in the wrong direction. That’s how novelists get deflated and novels get dropped. Plot those two elements first and the rest is just a matter of connecting two dots.

By the way, if you haven't read Joseph Finder, my favorites are Paranoia and Killer Instinct. Looking at the plot diagram, both of those novels have a great set-up and a knockout payoff.

Get a FREE ebook of my crime stories.

The great thriller writer Joseph Finder told me that figuring out the end of the novel is a key to getting started. “Gotta know the destination,” he said. (More from Joseph on plot.)

The great thriller writer Joseph Finder told me that figuring out the end of the novel is a key to getting started. “Gotta know the destination,” he said. (More from Joseph on plot.)Take a look at my diagram of the outline for a thriller (You've seen it before). The two pieces I fill in first are the Set Up in Act I and the Payoff in Act III, where the hero prevents whatever the bad guy aims to do.

Why do it that way? Because you gotta know the destination before you start on the journey. If you don’t, you’ll meander. That nice rising diagonal line across the diagram will droop and zig zag -- and that means losing momentum. You’ll waste a lot of energy going in the wrong direction. That’s how novelists get deflated and novels get dropped. Plot those two elements first and the rest is just a matter of connecting two dots.

By the way, if you haven't read Joseph Finder, my favorites are Paranoia and Killer Instinct. Looking at the plot diagram, both of those novels have a great set-up and a knockout payoff.

Get a FREE ebook of my crime stories.

Published on March 20, 2014 14:10

•

Tags:

crime-fiction, how-to-write, joseph-finder, plotting, thrillers, write-a-thriller, writing, writing-tips

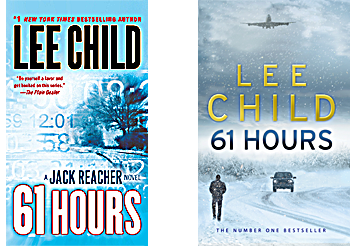

If you read only one Lee Child thriller, read '61 Hours'

Child’s evocation of the Dakota winter shows how well he writes

Lee Child is justly famous for creating a compelling main character in the loner Jack Reacher and for building plots that turn the pages for you -- and fast.

In 61 Hours Lee Child shows how well he can create an atmosphere and a location. The frozen tundra of Dakota is the setting and it’s almost a character in the plot. After I read 61 Hours I went back to some other Child novels and saw that he had written just as strongly about the often lonely locales of Nebraska and Indiana in other Reacher books. But it hadn’t struck me quite as forcefully as the chilly reaches of Dakota. Still it was there and it demonstrates the quality of Child’s work.

It also highlights the deftness of Child's writing in general. Reviewers write about Child as the ultimate page-turner. It's a guilty pleasure, writes one chap in The Guardian, that comes out in conversation only when you realize that others are addicted.

It also highlights the deftness of Child's writing in general. Reviewers write about Child as the ultimate page-turner. It's a guilty pleasure, writes one chap in The Guardian, that comes out in conversation only when you realize that others are addicted.

I don't see it that way, and 61 Hours demonstrates why. Page-turner, I think, implies that the writing doesn't get in the way. It doesn't make you pause to think: "What does the writer mean by this phrase?" Yet without bogging down in too much description, Child creates a visceral sense of the Dakota winter.

In fact the sense of place in Child's books is at least as strong as the sense of Reacher as a character. Often the titles of Child's novels are a bit forgettable (though '61 Hours' is memorable because it relates to something specific within the plot). So the way I remember them is, "Oh, that's the one that takes place in Boston and in a remote spot in Maine." You see, the anchor is the place.

Perhaps that's because Child is a Brit living in America. Maybe it gives him a heightened awareness of place.

All the Jack Reacher books are wonderful. Which is your favorite? Let me know.

Get a FREE ebook of my crime stories.

Read more If you read only one... For the indispensable book by each big thriller writer.

Lee Child is justly famous for creating a compelling main character in the loner Jack Reacher and for building plots that turn the pages for you -- and fast.

In 61 Hours Lee Child shows how well he can create an atmosphere and a location. The frozen tundra of Dakota is the setting and it’s almost a character in the plot. After I read 61 Hours I went back to some other Child novels and saw that he had written just as strongly about the often lonely locales of Nebraska and Indiana in other Reacher books. But it hadn’t struck me quite as forcefully as the chilly reaches of Dakota. Still it was there and it demonstrates the quality of Child’s work.

It also highlights the deftness of Child's writing in general. Reviewers write about Child as the ultimate page-turner. It's a guilty pleasure, writes one chap in The Guardian, that comes out in conversation only when you realize that others are addicted.

It also highlights the deftness of Child's writing in general. Reviewers write about Child as the ultimate page-turner. It's a guilty pleasure, writes one chap in The Guardian, that comes out in conversation only when you realize that others are addicted.I don't see it that way, and 61 Hours demonstrates why. Page-turner, I think, implies that the writing doesn't get in the way. It doesn't make you pause to think: "What does the writer mean by this phrase?" Yet without bogging down in too much description, Child creates a visceral sense of the Dakota winter.

In fact the sense of place in Child's books is at least as strong as the sense of Reacher as a character. Often the titles of Child's novels are a bit forgettable (though '61 Hours' is memorable because it relates to something specific within the plot). So the way I remember them is, "Oh, that's the one that takes place in Boston and in a remote spot in Maine." You see, the anchor is the place.

Perhaps that's because Child is a Brit living in America. Maybe it gives him a heightened awareness of place.

All the Jack Reacher books are wonderful. Which is your favorite? Let me know.

Get a FREE ebook of my crime stories.

Read more If you read only one... For the indispensable book by each big thriller writer.

Published on March 25, 2014 05:38

•

Tags:

crime-fiction, crime-novel, how-to-write, if-you-read-only-one, lee-child, thriller

Write a thriller: Bad experiences make you a better writer

Remember how it feels to feel bad, endure it positively, and write it down

When something bad happens to a writer, the experience is great material for something bad happening to your characters. Remember the feelings, the way your mind processed it and the sensations of tension in your heart, your veins. Get it all down on paper and save it for when you need to give those emotions to a character. The experience can teach you how to be a better person and how to be a better writer.

This ought to make you feel better at those low times. Because you know it’ll come in useful.

British writer Alan Bennett is known for his mordant wit, for making dour experiences seem somehow wistful and alive. “For a writer, nothing is ever quite as bad as it is for other people,” Bennett writes, “because, however dreadful, it may be of use.”

Negative experiences can change you as a person -- for the better, if you approach them positively.

The Roman emperor and stoic philosopher Marcus Aurelius wrote that a negative experience should be recognized for what it is: something that has happened, and nothing more. Our response is far more important than the event itself. "What is there in this that is unbearable and beyond endurance?" he wrote. The answer is: Nothing at all.

With that attitude you can take the negative experience and use it for your fiction, while also growing spiritually with a sense of acceptance.

Read more Write a thriller posts with tips and analysis from Stephen King, Raymond Chandler, Dan Brown, and many other great novelists.

Get a FREE ebook of my crime stories.

When something bad happens to a writer, the experience is great material for something bad happening to your characters. Remember the feelings, the way your mind processed it and the sensations of tension in your heart, your veins. Get it all down on paper and save it for when you need to give those emotions to a character. The experience can teach you how to be a better person and how to be a better writer.

This ought to make you feel better at those low times. Because you know it’ll come in useful.

British writer Alan Bennett is known for his mordant wit, for making dour experiences seem somehow wistful and alive. “For a writer, nothing is ever quite as bad as it is for other people,” Bennett writes, “because, however dreadful, it may be of use.”

Negative experiences can change you as a person -- for the better, if you approach them positively.

The Roman emperor and stoic philosopher Marcus Aurelius wrote that a negative experience should be recognized for what it is: something that has happened, and nothing more. Our response is far more important than the event itself. "What is there in this that is unbearable and beyond endurance?" he wrote. The answer is: Nothing at all.

With that attitude you can take the negative experience and use it for your fiction, while also growing spiritually with a sense of acceptance.

Read more Write a thriller posts with tips and analysis from Stephen King, Raymond Chandler, Dan Brown, and many other great novelists.

Get a FREE ebook of my crime stories.

Published on April 03, 2014 23:07

•

Tags:

alan-bennett, crime-fiction, how-to-write, marcus-aurelius, thrillers, write-a-thriller, writing-tips

How to write a Midpoint that gives new impetus to your plot

The Midpoint is key to the pace of a thriller -- and many other genres

By Matt Rees

When you plot a novel, pay special attention to the plot point called the Midpoint. Write a good Midpoint and you’ll propel your readers into the second half of your book with spectacular impetus.

What is the Midpoint? It falls directly in the center of the story structure (which may not be precisely in the middle of the book by page number, but probably is close.) The Midpoint is a scene that shifts the context and momentum of the story. It could be big or small. It could shift the story 45 degrees or 180. But it absolutely must push the story up a gear or two.

The main result of the Midpoint is a change in the hero. In the first half of Act II, the hero reacts to the situation around him. At the Midpoint, the hero becomes an action figure, powering through the second half of Act II in a more proactive mode.

Jane Austen, thriller novelist

Jane Austen, thriller novelist

That doesn’t mean this only works for action heroes. That master of the thriller genre Jane Austen writes a classic Midpoint in Pride and Prejudice, when Mister D’Arcy proposes to Lizzie Bennett, only for her to reject him and tell him she hates all he stands for. After that, there’s no more dancing around each other, no coming together just because we like Lizzie and want her to marry a nice, rich guy. They have to act, or they aren’t going to end up as a couple.

Imagine your novel as a ship (at least, a ship contemporary to Miss Austen). The Midpoint is the mainmast, while the first and second plot points are the foremast up front and the mizzen at the back. Sure, there are ships with only two masts. But they don’t move as fast or as powerfully as a ship that’s built around a big, impressive, driving mainmast. Novels without a mainmast won’t move as quickly either, no matter how much wind the author supplies.

Midpoint story structure checklist

Here are a few ways to build a Midpoint that propels the hero into the second half of Act II with major momentum:

• Introduce a new character whose presence adds to the danger. In Gorky Park, Martin Cruz Smith gives his detective a new American pal who turns out to have a big impact on the denouement.

• Change the nature of the threat to the hero. Don Winslow does this in Satori and gives us a 180 degree twist. The reader spends the first half of the book thinking the hero has to carry out a hit for the CIA to buy his freedom from a US military jail. Instead, at the Midpoint, Winslow delivers a plot-point double punch. The hero kills his target — at great risk and with much tension. Only to have the CIA immediately try to kill him. For the rest of the book, he faces entirely unexpected risks as he figures out why he was double-crossed and goes after the men he believes did it.

• Introduce new information. Bridget Jones learns her boyfriend Mark is involved with another woman in Bridget Jones’s Diary. Jack Reacher finds reason to suspects the woman he’s involved with might be the killer in The Affair.

• Kill someone, to heighten the element of danger and provide a new impetus for the hero’s chase. I admit I like this one. I’ve used it in several of my novels. In Mozart’s Last Aria, the great composer’s sister is about to learn who killed him, only for her informant to be murdered during a performance of “The Magic Flute.” She’s back to square one, but now she’s sure there’s a murderer and that he’s onto her.

The show 24 tends to use the 180-degree Midpoint, too. Ever noticed how Jack Bauer fights one lot of bad guys for the first 12 hours, only to realize halfway through the season that the real bad guy is someone else entirely with a completely different plan?

What does a good Midpoint do?

A good Midpoint moves the plot faster. But best of all the reader experiences the same startling shift in focus as the hero. That creates tension and conflict. Which is a good thing in any plot. It’s also a way of saying to the reader, “Gotcha. Stay tuned, because I have more like that for Act III.”

Always try to make the Midpoint blow your readers away. Devote as much energy and ingenuity to it as you do to the set-up of the novel. Never make it so subtle it passes unnoticed. Think of The Da Vinci Code. The Midpoint of Dan Brown's novel is the discovery of what the Holy Grail really is. That’s pretty earth-shattering, even as Midpoints go.

Got a clock? Find the Midpoint

Screenwriters tend to be particularly precise about having their Midpoint land exactly 50 percent of the way through the movie. Midpoint-spotting in movies is, therefore, pretty easy (provided you own a clock) and can be very instructive as a plot exercise.

Screenwriters tend to be particularly precise about having their Midpoint land exactly 50 percent of the way through the movie. Midpoint-spotting in movies is, therefore, pretty easy (provided you own a clock) and can be very instructive as a plot exercise.

Check out Casablanca. At the exact middle of the movie, Rick harshes out at Ilsa. She runs off. He's left in the bar thinking about what a terrible man he has become. Which propels him to spend the second half of the movie redeeming himself.

Let me know if there's a great Midpoint that I haven't mentioned.

Get a FREE ebook of my crime stories.

By Matt Rees

When you plot a novel, pay special attention to the plot point called the Midpoint. Write a good Midpoint and you’ll propel your readers into the second half of your book with spectacular impetus.

What is the Midpoint? It falls directly in the center of the story structure (which may not be precisely in the middle of the book by page number, but probably is close.) The Midpoint is a scene that shifts the context and momentum of the story. It could be big or small. It could shift the story 45 degrees or 180. But it absolutely must push the story up a gear or two.

The main result of the Midpoint is a change in the hero. In the first half of Act II, the hero reacts to the situation around him. At the Midpoint, the hero becomes an action figure, powering through the second half of Act II in a more proactive mode.

Jane Austen, thriller novelist

Jane Austen, thriller novelistThat doesn’t mean this only works for action heroes. That master of the thriller genre Jane Austen writes a classic Midpoint in Pride and Prejudice, when Mister D’Arcy proposes to Lizzie Bennett, only for her to reject him and tell him she hates all he stands for. After that, there’s no more dancing around each other, no coming together just because we like Lizzie and want her to marry a nice, rich guy. They have to act, or they aren’t going to end up as a couple.

Imagine your novel as a ship (at least, a ship contemporary to Miss Austen). The Midpoint is the mainmast, while the first and second plot points are the foremast up front and the mizzen at the back. Sure, there are ships with only two masts. But they don’t move as fast or as powerfully as a ship that’s built around a big, impressive, driving mainmast. Novels without a mainmast won’t move as quickly either, no matter how much wind the author supplies.

Midpoint story structure checklist

Here are a few ways to build a Midpoint that propels the hero into the second half of Act II with major momentum:

• Introduce a new character whose presence adds to the danger. In Gorky Park, Martin Cruz Smith gives his detective a new American pal who turns out to have a big impact on the denouement.

• Change the nature of the threat to the hero. Don Winslow does this in Satori and gives us a 180 degree twist. The reader spends the first half of the book thinking the hero has to carry out a hit for the CIA to buy his freedom from a US military jail. Instead, at the Midpoint, Winslow delivers a plot-point double punch. The hero kills his target — at great risk and with much tension. Only to have the CIA immediately try to kill him. For the rest of the book, he faces entirely unexpected risks as he figures out why he was double-crossed and goes after the men he believes did it.

• Introduce new information. Bridget Jones learns her boyfriend Mark is involved with another woman in Bridget Jones’s Diary. Jack Reacher finds reason to suspects the woman he’s involved with might be the killer in The Affair.

• Kill someone, to heighten the element of danger and provide a new impetus for the hero’s chase. I admit I like this one. I’ve used it in several of my novels. In Mozart’s Last Aria, the great composer’s sister is about to learn who killed him, only for her informant to be murdered during a performance of “The Magic Flute.” She’s back to square one, but now she’s sure there’s a murderer and that he’s onto her.

The show 24 tends to use the 180-degree Midpoint, too. Ever noticed how Jack Bauer fights one lot of bad guys for the first 12 hours, only to realize halfway through the season that the real bad guy is someone else entirely with a completely different plan?

What does a good Midpoint do?

A good Midpoint moves the plot faster. But best of all the reader experiences the same startling shift in focus as the hero. That creates tension and conflict. Which is a good thing in any plot. It’s also a way of saying to the reader, “Gotcha. Stay tuned, because I have more like that for Act III.”

Always try to make the Midpoint blow your readers away. Devote as much energy and ingenuity to it as you do to the set-up of the novel. Never make it so subtle it passes unnoticed. Think of The Da Vinci Code. The Midpoint of Dan Brown's novel is the discovery of what the Holy Grail really is. That’s pretty earth-shattering, even as Midpoints go.

Got a clock? Find the Midpoint

Screenwriters tend to be particularly precise about having their Midpoint land exactly 50 percent of the way through the movie. Midpoint-spotting in movies is, therefore, pretty easy (provided you own a clock) and can be very instructive as a plot exercise.

Screenwriters tend to be particularly precise about having their Midpoint land exactly 50 percent of the way through the movie. Midpoint-spotting in movies is, therefore, pretty easy (provided you own a clock) and can be very instructive as a plot exercise.Check out Casablanca. At the exact middle of the movie, Rick harshes out at Ilsa. She runs off. He's left in the bar thinking about what a terrible man he has become. Which propels him to spend the second half of the movie redeeming himself.

Let me know if there's a great Midpoint that I haven't mentioned.

Get a FREE ebook of my crime stories.

Published on April 09, 2014 01:09

•

Tags:

casablanca, crime-fiction, historical-fiction, how-to-write, jane-austen, midpoint, story-structure, thrillers, writing-tips

Write a thriller: Make it funny

Comedy is a great way to draw readers to a character

Thriller writers need to make their characters—particularly the hero—appealing to readers. That’s not always easy, because even the hero of a thriller might have to do some unappealing, nasty things to escape the bad guys and save the day. One important tool in the writer’s box is humor.

We like funny guys. Even when their humor is dark. Take Elmore Leonard’s Chili Palmer in “Get Shorty.” An old friend inquires about a mutual acquaintance in Florida:

Reptition of lines can build a character too. In “Get Shorty,” Chili instructs Harry, a movie producer, about how to take control of a conversation with a mobster. “Look at me,” he says. What the mobster is supposed to see is the toughness underlying Chili’s cheerful exterior. The humor comes when Harry uses the line on Ray Barboni, a Miami gangster who believes he’s owed money. Barboni sees Harry's weakness and superficiality--and no toughness. “Look at this,” Ray says to Harry, as he smashes a telephone across his nose.

Elmore Leonard recognized the importance of humor when building his “style” early on. He wrote of Hemingway that “He was my first big influence because he made writing look easy. Then I realized that Hemingway didn’t have much of a sense of humor.”

So Elmore took the apparent simplicity of Hemingway’s style and added what he called “attitude.” That’s where the humor often comes in. Elmore gives his character an “attitude,” which is typically built on speech tics and repeated tropes.

Language that might be considered “stupid cool” is one of Elmore’s techniques for creating attitude. Quentin Tarantino bastardized it, but Elmore never abused it. When one of his characters calls Barboni’s choice of weapon “the fucking Fiat of guns,” it’s funny. But it’s funnier because Barboni immediately shoots the guy dead with the Fiat of guns.

Now that Elmore’s dead, the best place to look for humor in a thriller—particularly humor that adds depth to character—is in the books of Keith Thomson. Thomson’s the new Elmore Leonard.

In “Once a Spy,” the main character, Charlie, is in debt to a loan shark. He needs a favor from a fairly dumb pal. Here’s a bit of their dialogue:

That’s funny. But what makes it even better is to read it with the next line:

Like Elmore Leonard, what Thomson does here is leave the laughing to the reader. The characters are into their discussion on a serious level. They aren’t wisecracking. They aren’t trying to be funny. They ARE funny, because their character is being revealed. But they don’t know it. That’s the trick.

Get a FREE ebook of my crime stories.

Get a FREE ebook of my crime stories.

Thriller writers need to make their characters—particularly the hero—appealing to readers. That’s not always easy, because even the hero of a thriller might have to do some unappealing, nasty things to escape the bad guys and save the day. One important tool in the writer’s box is humor.

We like funny guys. Even when their humor is dark. Take Elmore Leonard’s Chili Palmer in “Get Shorty.” An old friend inquires about a mutual acquaintance in Florida:

“How is Momo these days?”

“Dead.”

Reptition of lines can build a character too. In “Get Shorty,” Chili instructs Harry, a movie producer, about how to take control of a conversation with a mobster. “Look at me,” he says. What the mobster is supposed to see is the toughness underlying Chili’s cheerful exterior. The humor comes when Harry uses the line on Ray Barboni, a Miami gangster who believes he’s owed money. Barboni sees Harry's weakness and superficiality--and no toughness. “Look at this,” Ray says to Harry, as he smashes a telephone across his nose.

Elmore Leonard recognized the importance of humor when building his “style” early on. He wrote of Hemingway that “He was my first big influence because he made writing look easy. Then I realized that Hemingway didn’t have much of a sense of humor.”

So Elmore took the apparent simplicity of Hemingway’s style and added what he called “attitude.” That’s where the humor often comes in. Elmore gives his character an “attitude,” which is typically built on speech tics and repeated tropes.

Language that might be considered “stupid cool” is one of Elmore’s techniques for creating attitude. Quentin Tarantino bastardized it, but Elmore never abused it. When one of his characters calls Barboni’s choice of weapon “the fucking Fiat of guns,” it’s funny. But it’s funnier because Barboni immediately shoots the guy dead with the Fiat of guns.

Now that Elmore’s dead, the best place to look for humor in a thriller—particularly humor that adds depth to character—is in the books of Keith Thomson. Thomson’s the new Elmore Leonard.

In “Once a Spy,” the main character, Charlie, is in debt to a loan shark. He needs a favor from a fairly dumb pal. Here’s a bit of their dialogue:

“I’m short by north of fifteen. If I don’t have it by tomorrow night, Grudzev’s going to fill a cup with sand.”

“And make you drink it?”

“Why would I care if he’s just filling a cup with sand?”

That’s funny. But what makes it even better is to read it with the next line:

“I’m short by north of fifteen. If I don’t have it by tomorrow night, Grudzev’s going to fill a cup with sand.”

“And make you drink it?”

“Why would I care if he’s just filling a cup with sand?”

“That could kill you, couldn’t it?”

Like Elmore Leonard, what Thomson does here is leave the laughing to the reader. The characters are into their discussion on a serious level. They aren’t wisecracking. They aren’t trying to be funny. They ARE funny, because their character is being revealed. But they don’t know it. That’s the trick.

Get a FREE ebook of my crime stories.

Get a FREE ebook of my crime stories.

Published on May 30, 2014 00:46

•

Tags:

alan-bennett, crime-fiction, elmore-leonard, how-to-write, humor, keith-thomson, marcus-aurelius, thrillers, write-a-thriller, writing-tips