Matt Rees's Blog - Posts Tagged "writing-life"

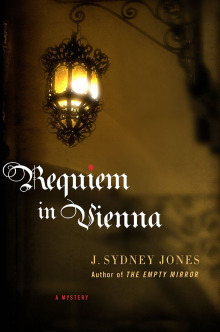

From Hitler History to Mahler Mystery: J. Sydney Jones’s Writing Life

Some authors exude the pleasure of reading and writing (and, believe me, when you meet them, you’d be surprised how many just don’t.) J. Sydney Jones is such a writer, with a breadth of writing experience in an array of genres that’s highly impressive and carries with it an obvious love of his craft. His Viennese Mystery series is a fascinating way to delve into one of Europe’s loveliest, most cultured cities – and damned entertaining, too. He’s also the man behind a great new blog Scene of the Crime, which focuses on the role of place in crime fiction – check out Syd’s interview with Berlin noirmeister Philip Kerr. Here Syd discusses his career and his ideas about writing.

Some authors exude the pleasure of reading and writing (and, believe me, when you meet them, you’d be surprised how many just don’t.) J. Sydney Jones is such a writer, with a breadth of writing experience in an array of genres that’s highly impressive and carries with it an obvious love of his craft. His Viennese Mystery series is a fascinating way to delve into one of Europe’s loveliest, most cultured cities – and damned entertaining, too. He’s also the man behind a great new blog Scene of the Crime, which focuses on the role of place in crime fiction – check out Syd’s interview with Berlin noirmeister Philip Kerr. Here Syd discusses his career and his ideas about writing.How long did it take you to get published?

I started out in journalism, so I had a sense of accomplishment right off, publishing my travel pieces in newspapers and magazines all over the place. Books are a different animal, but again I went with travel first and had some good early success with walking, hiking, and cycling guides. I wrote eight novels, though, before I got my first one, Time of the Wolf, published.

With the current “Viennese Mystery” series, things were easier. I had a bit of an author platform with several well-received books about Vienna and an agent who is most savvy. First query landed us the book deal.

Would you recommend any books on writing?

Tried and trusted here: you can look a lot further and do a lot worse than E.M Forster’s Aspects of the Novel. Another classic is Percy Lubbock’s The Craft of Fiction. These will not be everyone’s cup of tea, but I just love the erudite discussions in both.

What’s a typical writing day?

I get to work about nine in the morning after I drop my son off at school. I try to devote the first hours of the writing day to the current fiction project--currently the fourth book in the Viennese Mystery series. Then some exercise--tennis, if I am lucky--and lunch, followed by more mundane freelance stuff in the afternoon that also helps to pay the bills.

Plug your latest book. What’s it about? Why’s it so great?

Each of the books in the Viennese Mystery series features a famous historical figure of Vienna 1900. Requiem in Vienna focuses on musical Vienna: the composer Gustav Mahler is the target of an assassin and my protagonist, the lawyer and private inquiries man, Karl Werthen, is hired to protect him. The books are a blend of historical whodunit and literary thriller with more than a dash of historical/cultural/food lore thrown in.

Here’s what a Kirkus Reviews critic had to say of the current series installment: “Sophisticated entertainment of a very high caliber.”

How much research is involved in each of your books?

There are decades of research in the books. Explanation: I started researching Vienna 1900 long ago for my book, Hitler in Vienna. Since then I have continued to read heavily in the period, but for each book I still need to bone up on the historical folks I am featuring. Some writer once said that research was sort of like writing without the creative sweat. I enjoy the research; I probably commit about three months to each before I even begin the plotting. And thank whomever for the Internet--I can even get full editions of Viennese papers of the time online.

Where’d you get the idea for your main character?

Karl Werthen is a successful lawyer and sometimes inquiry agent, an assimilated Jew, and a distinct Viennophile. And I haven’t got a clue to where he comes from, other than a shared love for Vienna. He just appeared full-formed on the first page of The Empty Mirror, the initial in the series. A minor character, he elbowed his way to the forefront by the end of the first draft; the series concept actually had the real-life father of criminology, Hanns Gross, as the protagonist. A crusty old curmudgeon, Gross tugs Werthen away from his safe wills and trusts gig back into criminal law in that first one, to prove the artist Gustav Klimt innocent of murdering his model. But it just worked out so much better to use Werthen as my lead and Gross, the pompous pro, as the sometimes sidekick.

What’s your experience with being translated?

Somewhat odd. For example, my Hitler in Vienna was first published in Germany. I originally queried publishers there in German, and it was bought sight unseen (Hitler, at the time, was a hot topic). When they received my doorstopper of a manuscript in English and realized it needed to be translated, they were none too pleased. But they sucked it up and published anyway.

Then when trying to sell the English-language rights, I had a hell of a time convincing editors in England and the U.S. that no, they would not have to have the book translated. I already had the English original of the manuscript.

What books have influenced you?

As a young man I loved the lyricism of Steinbeck. Lee from East of Eden is still one of my favorite fictional characters. And of course there was Hemingway and Fitzgerald. Then during the almost twenty years I lived in Vienna, I became an avid reader of nineteenth- and twentieth-century British authors. Blame it on the British Council. A wonderful resource in its day with massive armchairs around a humming ceramic stove. Thomas Hardy became my literary hero; I open one of his novels and begin reading his scene-setting on some desolate heath in the south of England, and I get actual chills. The language just works for me. And Conrad. Don’t even get me started on Conrad--and the bugger wrote in a second language! A guilty pleasure also became the works of J.B. Priestley, especially his Good Companions.

Did these books influence my writing? Who knows, but they surely have made my life fuller. Le Carre, of course, pushed me in new ways with dialogue and plot, as did the early fiction works of Paul Theroux (Saint Jack, Picture Palace). I wish I could make my dialogue sparkle and crack they way those guys do. But this catalogue could go on for some time. Basta.

Thanks, Syd. Fascinating insights.

Thanks for the opportunity to chat, Matt.

Published on February 18, 2010 02:11

•

Tags:

aspects-of-the-novel, austria, berlin, berlin-noir, crime-fiction, e-m-forster, exotic-fiction, fitzgerald, gustav-mahler, hemingway, hitler, interviews, j-sydney-jones, john-le-carre, joseph-conrad, karl-werthen, matt-beynon-rees, paul-theroux, percy-lubbock, philip-kerr, requiem-in-vienna, scene-of-the-crime, steinbeck, the-craft-of-fiction, vienna, writing-life

In between the drafts

Rock musicians like to note that, had they not discovered their talents for destroying ear-drums, they’d have been criminals. It adds some edge to their pampered personae. Here’s my claim to edge: had I not been a writer, I’d have been locked up long ago, but not in a jail. At best I’d have been sedated.

Rock musicians like to note that, had they not discovered their talents for destroying ear-drums, they’d have been criminals. It adds some edge to their pampered personae. Here’s my claim to edge: had I not been a writer, I’d have been locked up long ago, but not in a jail. At best I’d have been sedated.I know this for sure, because when I’m between drafts of a novel I feel the old madnesses creeping up on me. The dark resentments whose origins I can’t quite nail down. The tension around the center of my chest and the heavy breathing and the tight jaw and the voice in my head telling me this isn’t fair, whatever it is. The flickering fantasies penetrating my mind when it lacks the focus that otherwise keeps it calm.

My wife sees all this before I do, at least consciously. “Maybe you ought to work on something else while you’re waiting to start a new draft,” she says, gentle and delicate, as if she were waiting for me to respond with an angry “I’m all right, dammit."

I have to take a break, you see, because writing a novel requires for me at least 10 drafts. Read a book 10 times straight and see if you don’t get bored with it. Or really pissed off.

So when I get through a draft, I take a week or so before I get back into it. As the end of the draft approaches, I start to fret about that week. I can’t take an actual vacation, because I always tell myself that I don’t know precisely when I’ll reach the end of the draft and therefore I can’t book a trip in advance. I try to line up some reading related to the subject of the book, but sometimes the books turn out to be duds or I’m done with them in a day and a half.

This time, as I take a break between drafts of my novel about the great Italian painter of the early seventeenth century, Caravaggio, I find myself sweating it out in the desert heat of Jerusalem. Enervating, indeed. I’m already a little fevered in any case, because I’ve been deep in the psyche of Caravaggio, who was both a brilliant artist and a duelist with an explosive temper.

Read the rest of this post on my blog The Man of Twists and Turns.

Published on August 13, 2010 01:01

•

Tags:

caravaggio, crime-fiction, gaza, jerusalem, meditation, plays, playwright, writing, writing-life

Blissfully blogless

Last weekend, my computer played up. Suddenly I couldn’t post the fascinating blog item I had written. I couldn’t update my Facebook page.

Last weekend, my computer played up. Suddenly I couldn’t post the fascinating blog item I had written. I couldn’t update my Facebook page.The computer gave me some kind of message about a “Flash” that had “crashed.” I’m old enough to remember the sputtering rockets of Flash Gordon in the 1950s series that was rebroadcast on the BBC in the early 1970s when I was a kid. That image held off my sense of powerlessness and frustration for about a half minute.

Then I went nuts and hit myself in the head. Yes, full fist to the side of the head. As I watched the little dial on my screen telling me the computer was “still working on it”….on and on. Hit myself in the head six times.

Then I decided that it was stupid to be so frustrated over a computer. (I haven’t hit myself in the head for a decade, and that was when I was divorcing my first wife, so I consider it to be far more excusable, though no less daft.) In fact, I realized that this Flash-crash might actually save me from the attention-deficit disorder known as “writing a blog” and “having a profile online.”

I’m told these things are good for an author, to build a public awareness of his work. But what would happen if I didn’t do them? Suddenly I faced the prospect of (a) getting my computer fixed, or (b) never filing to my blog or updating Facebook or Red Room or Goodreads or Crimespace or Twitter ever again. I liked the idea of prevaricating, so (a) seemed quite possible.

Read the rest of this post on my blog The Man of Twists and Turns.

Published on September 29, 2010 22:58

•

Tags:

alex-ruehle, blog, crime-fiction, crimespace, facebook, flash-gordon, goodreads, internet, red-room, sueddeutsche-zeitung, writing-life

Compelling seeds of true history: Philip Sington’s Writing Life interview

The best historical novels are based on some element of real history which has been either neglected or is little known. Philip Sington’s “The Einstein Girl” grows out of the revelation that Albert Einstein had a secret daughter. Sington takes that seed and, with the hand of a true thriller master, builds around it a story of psychiatry and love in the early days of Hitler’s Germany. It's one of the most beautiful and harrowing stories you’ll read. I met Philip, who was born in Cambridge, England, in 1962, on a recent evening in Darmstadt, Germany, where we both read excerpts from our books – in a church, on top of the tombs of the ancient Landgraves of Hesse. After hearing him read, I immediately took up “The Einstein Girl” and was utterly swept away by it. Here Philip discusses his Writing Life:

The best historical novels are based on some element of real history which has been either neglected or is little known. Philip Sington’s “The Einstein Girl” grows out of the revelation that Albert Einstein had a secret daughter. Sington takes that seed and, with the hand of a true thriller master, builds around it a story of psychiatry and love in the early days of Hitler’s Germany. It's one of the most beautiful and harrowing stories you’ll read. I met Philip, who was born in Cambridge, England, in 1962, on a recent evening in Darmstadt, Germany, where we both read excerpts from our books – in a church, on top of the tombs of the ancient Landgraves of Hesse. After hearing him read, I immediately took up “The Einstein Girl” and was utterly swept away by it. Here Philip discusses his Writing Life:How long did it take you to get published?

I got a deal with my second book, which I finished about seven years after starting the first. Between the two enterprises there was a bit of a gap, though.

Would you recommend any books on writing?

I never read any books on writing when I was starting out. That was probably a mistake. The best book I’ve seen subsequently is Master Class in Writing Fiction by Adam Sexton (published by McGraw Hill). You’re supposed to read a particular novel before each chapter, which is a good approach.

What’s a typical writing day?

Someone once said that the writing life involves brief intervals of creativity punctuated by long intervals of staring into the fridge. That about sums it up in my case. That said, since becoming a father three years ago, I’ve had to cut down on the fridge time.

Plug your latest book. What’s it about? Why’s it so great?

The Einstein Girl is a historical novel inspired by the relatively recent discovery that Albert Einstein had a daughter in secret. It’s set in 1932, on the eve of the Nazi assumption of power, when Einstein was poised to flee Europe for America, and unfolds as a psychological mystery. I was inspired to write it because, in the course of my researches, I began to see some fascinating parallels between Einstein’s intellectual obsessions and his highly unusual private life.

How much of what you do is:

a) formula dictated by the genre within which you write?

b) formula you developed yourself and stuck with?

c) as close to complete originality as it’s possible to get each time?

In sketching out a book I’m guided more by instinct than anything. I think that’s something writers develop over time, and which becomes sharper the more they write. I don’t think I’ve ever adjusted a story because I don’t see it conforming to a model. More likely I’ll adjust it because I don’t find it satisfying or compelling enough.

What’s your favorite sentence in all literature, and why?

Did I mention that when I was fifteen I took it out of my pants and whacked off on the 107 bus from New York?

Philip Roth, Portnoy’s Complaint.

If you are going to indulge in rhetorical questions, make them good ones.

Read the rest of this post on my blog The Man of Twists and Turns.<\a>

Published on October 17, 2010 00:51

•

Tags:

adam-sexton, albert-einstein, crime-fiction, germany, historical-fiction, hitler, humbert-humbert, interviews, lolita, master-class-in-writing-fiction, philip-roth, philip-sington, portnoy-s-complaint, the-einstein-girl, writing-life

Swallow semen, identify penis: Helen Fitzgerald’s Writing Life interview

It will be a long time before anyone thinks of a better way to open their first novel than this: “My best friend Sarah was asleep. Her husband was lying beside her, and I was swallowing his semen.” That’s paragraph two of “Dead Lovely” by Helen Fitzgerald, a fabulous crime novel which manages to amuse, titillate and disturb. Since she published Dead Lovely in 2008, Helen has released three more adult titles and a teen novel. Born in Australia, she lives in Glasgow, Scotland, where she’s married to a Scot of Italian origin. We shared the stage at a German crime fiction festival in Menden, near Dortmund, late this summer, bonding over writing and Tuscany. In person she’s as amusing as her books, and when she talks about writing it’s with a mix of unassuming practicality and deep insight, as you’ll see from this interview.

It will be a long time before anyone thinks of a better way to open their first novel than this: “My best friend Sarah was asleep. Her husband was lying beside her, and I was swallowing his semen.” That’s paragraph two of “Dead Lovely” by Helen Fitzgerald, a fabulous crime novel which manages to amuse, titillate and disturb. Since she published Dead Lovely in 2008, Helen has released three more adult titles and a teen novel. Born in Australia, she lives in Glasgow, Scotland, where she’s married to a Scot of Italian origin. We shared the stage at a German crime fiction festival in Menden, near Dortmund, late this summer, bonding over writing and Tuscany. In person she’s as amusing as her books, and when she talks about writing it’s with a mix of unassuming practicality and deep insight, as you’ll see from this interview.How long did it take you to get published?

My husband is a screenwriter and he made it look very easy – most of his films seemed to make it to the big or small screen, and the word count for a screenplay was enticingly small (lots of lovely white spaces on the page). So I thought “If he can do this, I can!” I spent five years writing screenplays before realising that it was hard, and that I was a spectacular failure at it. One of my screenplays came very close to being green-lit. I decided that if this wasn’t produced, I’d write a book (which was what I’d always wanted to do, really). It didn’t get made, so I sat down and turned the treatment into my first book, Dead Lovely. It took three months. And another three before Faber and Faber bought it. So, my first answer is that it took me years to get published. My second is that it took three months.

Would you recommend any books on writing?

The only books I’ve ever read on writing are screenwriting books. Initially, I read everything I could get my hands on, but the only one I remember is How to Write Screenplays That Sell by Michael Hague. This book helped a great deal with structure, plot and characterization. It’s probably because of my background in screenwriting, and the lessons I learned from this book, that my novels have three acts and are easy to adapt into screenplays.

What’s a typical writing day?

Mostly I work at home in an office in the attic. I get the kids off to school, answer emails and do admin for a while, then settle down to a few hours writing before they arrive home again. My husband works in the office next door to mine, so we often yell strange things to each other through the walls like “Can you dissolve a body?” If I have a deadline, or if I’m really motivated by an idea, I can work all day and all night. My husband and I are pretty flexible and work well as a team, giving each other time off from domestic duties if one is on a roll. About three days a week, I head into Glasgow City centre, where I’ve rented a desk space in a studio. I missed having colleagues and life around me, and I love being shamed into productivity by other hard working people.

Plug your latest book. What’s it about? Why’s it so great?

Bloody Women is about a woman who’s about to get married to her Italian fiancé and leave Scotland to live with him in Tuscany. Before leaving her home, she decides to meet up with her ex-boyfriends to tie up loose ends and make sure she’s doing the right thing. Problem is, her exes all wind up dead, and she gets the blame. The book was fun to write and I believe it’s fun to read. It’s also pretty dark, looking at bi-polar disorder and a nasty-pasty serial killer.

Read the rest of this post on my blog The Man of Twists and Turns.

Published on November 07, 2010 08:42

•

Tags:

dead-lovely, dortmund, helen-fitzgerald, interviews, menden, michael-hague, mord-am-hellweg, screenplays, writers, writing-life

A Voice for her People: Susan Abulhawa’s Writing Life interview

Susan Abulhawa is a unique voice in contemporary fiction. She’s a Palestinian, born in Kuwait to a refugee family. She spent some years in an orphanage in East Jerusalem, her ancestral city, before university education in the US and she now lives near Philadelphia. She’s the founder of a wonderful charity, Playgrounds for Palestine, which aims to bring merry-go-rounds, slides and see-saws to the children of the West Bank and Gaza, as well as to refugee camps in Syria and Lebanon. As you’ll see from this interview, Susan’s writing life revolves around a leap she made at which many would balk. So that she could write her wonderful novel

Mornings in Jenin

, she mortgaged her house, went to a war zone, and returned with a passionate drive to write. What she wrote is a wrenching portrayal of a Palestinian family from 1948 – the foundation of Israel, which Palestinians call the “nakba,” the catastrophe – on through the civil war in Beirut and the second intifada. Mornings in Jenin is a bestseller whose poetic prose carries the resonance of the best Arabic fiction (writing which, due to the relative paucity of translation into English, we rarely get to enjoy; Susan wrote her novel in English). This many-faceted book has at its heart the most profound and tragic love-story imaginable. As a depiction of a violent history and of the bonds between lovers and siblings, Abulhawa’s novel gives a human voice to a people so often cast as a stereotype. How does she do it? Here’s what she has to say:

Susan Abulhawa is a unique voice in contemporary fiction. She’s a Palestinian, born in Kuwait to a refugee family. She spent some years in an orphanage in East Jerusalem, her ancestral city, before university education in the US and she now lives near Philadelphia. She’s the founder of a wonderful charity, Playgrounds for Palestine, which aims to bring merry-go-rounds, slides and see-saws to the children of the West Bank and Gaza, as well as to refugee camps in Syria and Lebanon. As you’ll see from this interview, Susan’s writing life revolves around a leap she made at which many would balk. So that she could write her wonderful novel

Mornings in Jenin

, she mortgaged her house, went to a war zone, and returned with a passionate drive to write. What she wrote is a wrenching portrayal of a Palestinian family from 1948 – the foundation of Israel, which Palestinians call the “nakba,” the catastrophe – on through the civil war in Beirut and the second intifada. Mornings in Jenin is a bestseller whose poetic prose carries the resonance of the best Arabic fiction (writing which, due to the relative paucity of translation into English, we rarely get to enjoy; Susan wrote her novel in English). This many-faceted book has at its heart the most profound and tragic love-story imaginable. As a depiction of a violent history and of the bonds between lovers and siblings, Abulhawa’s novel gives a human voice to a people so often cast as a stereotype. How does she do it? Here’s what she has to say:How long did it take you to get published?

It felt like forever. There was an 8 years span from the time I started writing Mornings in Jenin until it was finally published in 2010.

Would you recommend any books on writing?

I’ve never read a book on writing. I’m told that I should and I probably will one of these days. When I was writing Mornings in Jenin, I did get one as a gift. But I didn’t get beyond the first chapter. I don’t think my hesitation had anything to do with the book’s merits though. I just put it down when it talked about developing an outline or sketch of the story. I knew that I would never do that – write an outline or think ahead. So I just didn’t invest any more time in something that was going to lead me in a direction that my brain would not appreciate. I’m not a planner by nature. I follow my heart, usually into disasters and heartaches. But sometimes it takes me into miracles. Regardless, I’m just not very good at following instructions. The book I got was more or less that, or at least that’s how I perceived it and that’s why I put it down. That said, I just read Tony Parson’s answer to this exact question and he mentioned writing at least 1000 words a day. Apparently he got that advice from a book and I’m taking it from him. It’s a good bit of advice and has served me well for the past few days since I read it.

I’m sure Tony will be glad to hear it. What’s a typical writing day?

I would get up at 5am, make coffee, and sit at my keyboard and write straight through until it was time to wake my daughter up for school at 8am [she was in elementary at the time; now she’s up at 6 so that timing doesn’t work as well]. Then I’d start again from 9:30 until noon. The rest of the day I spent helping out at my daughter’s school, running or yoga, and a million other things single moms do.

That was then, when I had mortgaged my house for its full value so I could afford not to work and concentrate on writing. Now I’m paying off that mortgage and have to work a full time job as a medical writer, putting those biology degrees to some use. So I write when I can. Usually in the wee hours of the morning, in rare moments of blissful quiet and solitude, on trains, or when I’m depressed and therefore don’t care if everything else piles up.

How would you describe what “Mornings in Jenin” is about? And of course tell us why’s it so great?

It’s a story of love, and how that love is shaped by violence and persistent oppression – Love between a farmer and his land; between siblings; between a man and a woman; a mother and her children; a father and his children; love between friends. I think it’s up to readers to decide if it’s great or not. I’ll say that I put my heart into it. That ultimately my intentions in writing this story distilled to a single purpose – to be true to the characters by telling their stories with honestly, authenticity, and humanity.

Read the rest of this post on my blog

Published on April 08, 2011 01:24

•

Tags:

arabic, gaza, interviews, middle-east, mornings-in-jenin, palestine, palestinians, susan-abulhawa, west-bank, writers, writing-life

Getting Inside Your Head: Virtual Reality guru Jeremy Bailenson's Writing Life

Move over cards, cocaine, and nicotine, Virtual Reality is the new addiction. It isn’t restricted to the realms of academe or science fiction. Whether you know it or not, it’s going to change your life. It already may have done so. Stanford University Professor Jeremy Bailenson is co-author of a new book, Infinite Reality, which explains how our world is being altered by…a world that isn’t really there. A compelling thinker and one of the foremost young experts on VR, Bailenson’s book (on the shelves April 11) is sure to change the way you look at all aspects of the future and its intersection with rapidly developing technologies. With the arrival of “avatars” of ourselves, it might even change how you look at yourself. Here’s what he told me about his work and the new book:

Move over cards, cocaine, and nicotine, Virtual Reality is the new addiction. It isn’t restricted to the realms of academe or science fiction. Whether you know it or not, it’s going to change your life. It already may have done so. Stanford University Professor Jeremy Bailenson is co-author of a new book, Infinite Reality, which explains how our world is being altered by…a world that isn’t really there. A compelling thinker and one of the foremost young experts on VR, Bailenson’s book (on the shelves April 11) is sure to change the way you look at all aspects of the future and its intersection with rapidly developing technologies. With the arrival of “avatars” of ourselves, it might even change how you look at yourself. Here’s what he told me about his work and the new book:Before we get to writing, here’s a virtual reality question. How soon will governments and corporations be able to control our behavior with virtual reality? And how?

Children play video games for more time per day than they watch movies and read books combined. Video games are becoming more “immersive,” that is, closer and closer to virtual reality, each year. Whether or not governments will use the medium to “control” us is up for debate, but there is little doubt that the next generation of lawmakers will look to virtual reality first and other media second when shaping laws, creating entertainment, and conducting commerce.

How long did it take you to get this book published?

From start—phone call from an agent suggesting I write a book—to finish—book available in stores--the process was about three years.

What’s a typical writing day?

I wake up early, drink coffee, and get my best writing done between 7am and 10am, and typically put in another few hours in the afternoon. Some days are longer days on which I pound the prose for double digit hours but those are the exception, not the rule. It’s a marathon, not a sprint…

Plug “Infinite Reality.” How would you describe what it’s about? And of course why’s it so great?

Infinite Reality is a survival guide for anyone seeking to understand how the virtual revolution is changing life as we know it—for example psychology, religion, education, entertainment, relationships, and business. For the past fifteen years, Blascovich and I have been running experiments to understand what happens to the mind inside virtual reality, with the idea that “someday” the technology would be a part of the average person’s daily life. It turns out “someday” has arrived. Children between the ages of 6 and 16 spend over 8 hours per day using digital media, and Internet addiction is quickly becoming a rival to substance abuse and gambling. Infinite Reality gives readers the tools to understand what Virtual Reality is and how it will affect their lives.

What’s it like to co-write a book?

The great part is being able to bounce ideas off one another and to have another person who is a highly invested editor. In our penultimate edit, Jim and I sat side by side and read OUT LOUD every single word of the book, and then argued over prose, grammar, and content. We averaged about thirty minutes per page. Needless to say it was a grueling month.

What’s your favorite sentence in all literature, and why?

“Cyberspace. A consensual hallucination experienced daily by billions”. In the late seventies when William Gibson is setting the stage for the virtual revolution we are experiencing today, he really captured the essence of virtual reality. Today there are many people who prefer their “hallucinations” to the physical world.

You’re a fan of Gibson’s “Neuromancer.” Some people say his sci-fi fiction “invented” the internet and cyberspace. Is that true? Did fiction-writing actually lead to all these subsequent scientific developments?

Neuromancer was without a doubt what inspired me to become a scholar of avatars. Gibson’s unprecedented vision of cyberspace redefines what it means to be human—mortality is optional, people can transform their gender, age, and identity at the drop of a hat, and the notions of pleasure and pain move beyond the flesh. Indeed these themes are pervasive throughout my research and throughout our book Infinite Reality. I first read it in high school, and like many Stanford students I force to read it in my courses, I didn’t really “get it”. It’s a challenging read on the first try, and some of the big ideas take a few reads before they grab hold. I didn’t pick the book up again for about a decade, in my fifth year of graduate school, where I was floundering without direction in my research, running cognitive psychology experiments and then designing computer programs that mimicked thought. But before dropping out of academia altogether, one job advertisement in particular resonated with what I had read in Neuromancer, and I decided to give university life one more try. I took a research position at UCSB studying avatars. Since then, Neuromancer has been my crutch. Large government grants have been awarded to me for building and testing Gibson’s ideas. Academic papers are improved by Gibson quotes that sum up the big ideas of the research. PhD students walk out of my office with a copy when searching for dissertation topics. Undergraduates who can’t imagine the world without the “cyberspace” Gibson predicted (or perhaps facilitated) grumble about using it as a textbook in my lecture classes.

Read the rest of this post on my blog The Man of Twists and Turns.

Published on April 10, 2011 00:29

•

Tags:

black-sabbath, infinite-reality, interviews, jeremy-bailenson, neuromancer, richard-morgan, sci-fi, science-fiction, virtual-reality, william-gibson, writers, writing-life

From Romance to Corpses: Tess Gerritsen’s Writing Life

Tess Gerritsen started with romance, but soon realized that dead bodies were where it’s at. At least, dead bodies handled deftly by the two most compelling female series characters in thriller fiction, Detective Jane Rizzoli and Dr. Maura Isles. Her first books were romance novels, but after writing eight of them she switched to medical thrillers. The 25 million books she has sold prove that this was one plot twist she very much got right. The first of many, in fact. Tess is an absolute master at a particular kind of twist which does more than simply surprise the reader. Her plotting and pacing genius is such that each new element seems to set the actual book racing as fast as the reader’s pulse. I saw her at work in this way at a recent book festival in Dubai. At a social barbeque for the writers attending, we were chatting about an anecdotal incident from another writer’s student days. Tess took what had been a moderately disturbing moment for the writer and instantly rattled off enough nimble plot twists to structure the first quarter of a fast-paced thriller—so that those of us chatting around the roasted chickens were gasping and wishing for her to tell us how the story would end. That’s part of Tess Gerritsen’s tremendous gift. But once she has that idea, how does she proceed? Here’s what she has to say about her Writing Life:

Tess Gerritsen started with romance, but soon realized that dead bodies were where it’s at. At least, dead bodies handled deftly by the two most compelling female series characters in thriller fiction, Detective Jane Rizzoli and Dr. Maura Isles. Her first books were romance novels, but after writing eight of them she switched to medical thrillers. The 25 million books she has sold prove that this was one plot twist she very much got right. The first of many, in fact. Tess is an absolute master at a particular kind of twist which does more than simply surprise the reader. Her plotting and pacing genius is such that each new element seems to set the actual book racing as fast as the reader’s pulse. I saw her at work in this way at a recent book festival in Dubai. At a social barbeque for the writers attending, we were chatting about an anecdotal incident from another writer’s student days. Tess took what had been a moderately disturbing moment for the writer and instantly rattled off enough nimble plot twists to structure the first quarter of a fast-paced thriller—so that those of us chatting around the roasted chickens were gasping and wishing for her to tell us how the story would end. That’s part of Tess Gerritsen’s tremendous gift. But once she has that idea, how does she proceed? Here’s what she has to say about her Writing Life:You had a career in medicine before you published. But for how long

before you became a professional writer were you interested in writing?

I knew I was a writer at age seven. I wanted to apply to journalism school as a teen, but my father -- a very practical Chinese-American parent -- warned me that writing was no way to make a secure living. As an obedient Chinese daughter, I followed his advice and went to medical school instead. But a few years into being a doctor those old writing impulses reasserted themselves and while I was home on maternity leave with my sons, I wrote my first novels. A few years later, I realized that I really could make a living as a writer – and I've been one ever since.

How long did it take you to get published?

I wrote two practice manuscripts before my third was accepted. That was CALL AFTER MIDNIGHT, a romantic thriller that was published by Harlequin/Mira books. I wrote romances, and then wrote a thriller HARVEST, which was my first really big bestseller. I've stuck with thrillers since then.

Would you recommend any books on writing?

TELLING LIES FOR FUN AND PROFIT by Lawrence Block is my favorite advice book about the craft of writing. It's funny, it's snappy, and it's spot-on.

What’s a typical writing day?

Breakfast, coffee, exercise, and then four first-draft pages. Only when I've written those four pages do I call it a day. It usually takes me all day to produce those four pages.

Read the rest of this post on my blog The Man of Twists and Turns.

Published on April 17, 2011 05:40

•

Tags:

american-crime-fiction, crime-fiction, medical-thriller, tess-gerritsen, thriller, writers, writers-interviews, writing-life

Doctor knows life and death: Abraham Verghese’s Writing Life interview

If you were a book editor who wanted to create the perfect writer for a best-selling epic novel of an African-born doctor forced to take refuge in the U.S., you might pick someone from Ethiopia. Make him of Christian Indian parentage. Educate him in medicine and send him to the Iowa Writing Program. Make him work in top medical jobs with HIV patients who’d force him to examine his own prejudices. Get him to write a pair of acclaimed medical memoirs. Just to keep him on his toes, give him a demanding job as a professor at Stanford University Medical School. Name him Abraham Verghese, and you’d have one of the most compelling writers in world fiction these days, with an ability to bring big, societal issues into close personal focus. Oh, wait, somebody already created this guy. Here he is:

If you were a book editor who wanted to create the perfect writer for a best-selling epic novel of an African-born doctor forced to take refuge in the U.S., you might pick someone from Ethiopia. Make him of Christian Indian parentage. Educate him in medicine and send him to the Iowa Writing Program. Make him work in top medical jobs with HIV patients who’d force him to examine his own prejudices. Get him to write a pair of acclaimed medical memoirs. Just to keep him on his toes, give him a demanding job as a professor at Stanford University Medical School. Name him Abraham Verghese, and you’d have one of the most compelling writers in world fiction these days, with an ability to bring big, societal issues into close personal focus. Oh, wait, somebody already created this guy. Here he is:You’ve had a career in medicine that most doctors would envy and success as a writer that few memoirists or novelists attain. How do you manage both careers so well?

I think there is no separation between the two. My identity, beyond that of being a father, a son, a citizen and so on is completely that of being a physician, of having the privilege, the honor, the calling to serve. I am old-fashioned in that sense, and get much satisfaction from this sense of serving the profession, honoring its ideals, celebrating its grand history (in novels or memoirs), and in repeatedly professing my faith in the “Samaritan function” of being a physician (to use the late physician Robert Loeb's term). I resist the definition of the writer as somehow separate and divorced from my day job, as if it were akin to leaving work and performing burlesque after hours. I do subscribe to the notion as a form of research, exploring the truth. Having said that, I feel that the writing (no different than, say, the music if you are a musician, or the bump and grind if you do burlesque) has to stand on its own, has to work by the standards of the discerning literate reader for whom I write. He or she cares little, I suspect, what degree I have behind my name (and I don’t put M.D. behind my name on my books). Writing has to work by the standards by which writing works.

How long did it take you to get your first memoir published?

It was my fictional story, Lilacs, in the New Yorker in 1991 that led to my getting a contract to write, My Own Country. It came right after my five years at a small hospital in Johnson City, Tennessee, where, in a town of just 50,000 people, as an internist and infectious diseases specialist we were looking after nearly a hundred people with HIV infection, an unexpected number for that population. It turned out there was an explanation for that mystery, and I wanted to tell it. I go the contract to write it in 1991, just after graduating from the Iowa Writers Workshop. I actually wrote the book while working full time in El Paso at the teaching hospital at Texas Tech. I wrote it in my nights and weekends and it took four years.

Would you recommend any books on writing?

So many good ones. A new addition is Francine Prose’s Reading like a Writer: A Guide for People who Love Books. John Gardner's books, The Art of Fiction and Becoming a Novelist are still so precious, as is Eudora Welty's One Writer's Beginnings. But truly the most important thing to do is keep reading and keep writing. It is 99% perspiration and 1% inspiration.

What’s a typical writing day?

Given my day job all these years (which I love and which is who I am), writing for a set amount of time every day is not going to happen. Something that really helps is that I have a secret second office, without even a sign on the door, where I escape a few half days a week to write. It is a great source of peace and gives me time to be reflective and write. Of course, I also do a lot of writing at nights, early mornings and over the weekend, and sometimes that is hard on my family.

“Cutting for Stone” is an epic of two orphaned Ethiopian brothers. How would you describe its themes?

I think the themes are epic themes – of love and loss, success and failure, life and death. And how medicine and a career in it can save you or destroy you. And how love redeems us and seems to be the only thing that lasts.

Where did the idea for the novel come from?

All I had at the outset was an image of a beautiful Indian nun giving birth in a mission hospital in Africa, a place redolent with Dettol and carbolic acid scents, a place so basic, so unadorned, that nothing separates doctor and patient. You know what I mean: no layers of paperwork, cubicles, computers and forms--just a line of patients stretching out the door. That is all I had. I did not know the whole plot or how it ended.

Read the rest of this post on my blog The Man of Twists and Turns.

Published on April 22, 2011 05:41

•

Tags:

abraham-verghese, aids, cutting-for-stone, interviews, medical-fiction, writers, writing-life

The Reverse Orientalist: Kamal Abdel-Malek’s Writing Life Interview

When Kamal Abdel-Malek was a young student, he chose to study outside the Arab world, eventually becoming a professor at Brown and Princeton Universities in the US. It was the first step in the physical and intellectual journeys of this intriguing Egyptian writer. Born in Alexandria and now a teacher of Arabic literature at the American University in Dubai, Abdel-Malek’s latest publication (available in English) is perhaps his most important, because it answers many of the questions Westerners asked themselves about the Arab world since the 9/11 attacks almost a decade ago. Abdel-Malek’s technique is an unusual and compelling one, because instead of seeking to explain how Arabs are, in America in an Arab Mirror: Images of America in Arabic Travel Literature, 1668 to 9/11 and Beyond he shows how we look to them. It’s a reversal of what the Palestinian intellectual Edward Said noted in Westerners writing about the Middle East: When you read the perceptions of Arab writers about Western society, it shows as much about the Arab writer as it does about the country he’s observing. Kamal took time to explain more about this vitally important book and to talk about his life as a writer. Demonstrating his originality as a thinker, he’s also the first writer I’ve interviewed on this blog to give due credit to Dan Brown.

When Kamal Abdel-Malek was a young student, he chose to study outside the Arab world, eventually becoming a professor at Brown and Princeton Universities in the US. It was the first step in the physical and intellectual journeys of this intriguing Egyptian writer. Born in Alexandria and now a teacher of Arabic literature at the American University in Dubai, Abdel-Malek’s latest publication (available in English) is perhaps his most important, because it answers many of the questions Westerners asked themselves about the Arab world since the 9/11 attacks almost a decade ago. Abdel-Malek’s technique is an unusual and compelling one, because instead of seeking to explain how Arabs are, in America in an Arab Mirror: Images of America in Arabic Travel Literature, 1668 to 9/11 and Beyond he shows how we look to them. It’s a reversal of what the Palestinian intellectual Edward Said noted in Westerners writing about the Middle East: When you read the perceptions of Arab writers about Western society, it shows as much about the Arab writer as it does about the country he’s observing. Kamal took time to explain more about this vitally important book and to talk about his life as a writer. Demonstrating his originality as a thinker, he’s also the first writer I’ve interviewed on this blog to give due credit to Dan Brown.How long did it take you to get your latest book published?

Two years. America in an Arab Mirror was published in April by Palgrave Macmillan in New York.

Would you recommend any books on writing?

Yes, books like these are helpful: On Writing by Stephen King, Break into Fiction, First Draft by Buckham and Love, and of course the classic, The Elements of Style by Strunk and White.

What’s a typical writing day?

I teach during the day so the only time available is either early in the morning or late in the evening. The best time is in the morning, especially when I wake up after a good night sleep.

Plug your book. How would you describe what it’s about? And of course why’s it so great?

America in an Arab Mirror: Images of America in Arabic Travel Literature, 1668 to 9/11 and Beyond deals with Arab-American relations, cross-cultural communication, and cultural understanding in general. The New York Times published a good review of it on April 21, 2011. My interest in Arab-American encounters in history, literature, and the arts started over a decade ago. The accounts of Arab travelers to America have always fascinated me. I widely researched the topic and had opportunities to read papers on it at Princeton and Dartmouth where I greatly benefited from the comments and the questions posed by colleagues in the field of Arabic and Middle Eastern studies. A question that was raised by a Princeton Arabist after one of my talks on the topic was whether Arab writings on America could be regarded as a case of Occidentalism, a counter-Orientalism of sorts. In some ways this book is a reversal of what Edward Said described as the West’s Orientalist view of the East. One could say that its stories are an Arab way of saying, “We, too, can subjugate you, Westerners, to our tourist, voyeuristic gaze.”

What’s your favorite sentence in all literature, and why?

If the question is about “favorite lines” instead of “favorite sentence” then I would mention, without hesitation, the evocative lines uttered by Macbeth upon receiving the news of his wife’s death.

Life's but a walking shadow, a poor player,

That struts and frets his hour upon the stage,

And then is heard no more. It is a tale

Told by an idiot, full of sound and fury,

Signifying nothing.

Macbeth Act 5, scene 5

What’s the best descriptive image in all literature?

But let there be spaces in your togetherness and let the winds of the heavens dance between you. Love one another but make not a bond of love: let it rather be a moving sea between the shores of your souls. -- Khalil Gibran

The teacher who is indeed wise does not bid you to enter the house of his wisdom but rather leads you to the threshold of your mind. -- Khalil Gibran

Who’s the greatest stylist currently writing?

In Arabic I must mention Yusuf Idris, the greatest short story writer and playwright. In Arabic he employs the different register of modern Arabic and the very evocative expressions of the everyday spoken Egyptian colloquial. In my opinion he, not Naguib Mahfouz, should have received the Nobel Prize for Literature. Outside the Arab world one can mention Gabriel García Márquez.

Read the rest of this post on my blog The Man of Twists and Turns.

Published on May 08, 2011 06:38

•

Tags:

9-11, america-in-an-arab-mirror, arab-world, arab-writers, egypt, egyptian-writer, interviews, kamal-abdel-malek, middle-east, writers, writing-life