Matt Rees's Blog - Posts Tagged "biography"

The Last Man in London

Here's my latest post on the International Crime Authors Reality Check blog:

During my teens, my family lived in a house in Addington, at the very farthest reach of South London. At the bottom of the hill, the road made its final exit from London. Not quite wide enough for two cars, it traveled onto the North Downs of Kent. Sometimes I would ride my bike along the lane and up a hill overlooking the Downs and lie on the grass. I was the border between London and the rest of the world. When a car went by below, I’d send out a silent message to the driver: “You just passed the last man in London.”

Much of my time was spent looking in the opposite direction, wishing we lived in central London– where things happened, where the Underground came to your neighborhood, where there was life, damn it. Where I would feel at one with those around me. Not like “the last man,” the one at the edge of everything. Like any suburban teenager, I wanted to be anywhere else in the world but where I was. And central London was both elsewhere and not impossibly far away.

Most of my friends from that time and from university, too, ended up living and working right there in central London. Perhaps they knew it was the right place for them, or maybe they never cared to ask themselves that question. I knew it wasn’t what I wanted, and I never lived there. I went down the lane that wasn’t wide enough for two cars, and I never came back. If I hadn’t, I’m sure I’d still have written. But I doubt I would have seen as much or learned what I have about myself.

The Palestinian sleuth of my crime novels Omar Yussef is, for me, a satisfying character because he represents the insights I’ve gathered in distant, eventful travels. But he’s also a measure of my ability to understand the outsiders of other cultures. Not the people journalists typically rush toward–the prime ministers and generals and imams with their false rhetoric and their stake in things staying as they are. Rather they’re the people who seem to climb the same marginal hill that I mounted as a youth and look out wondering why their world isn’t better than it is. That’s the essence of Omar Yussef (and of the best “exotic detective” fiction).

That lane near our house went up onto the Downs and undulated toward Westerham, a beautiful place built around a sloping village green. At the center of the green, there’s a statue of General Wolfe, a native of the village who led British troops to victory against the French in Canada in the Seven Years War of the mid-Eighteenth Century. The latest historical research on Wolfe suggests he was a megalomaniac glory-hunter who got exactly the kind of heroic immortality he wanted when he died at the moment of victory in Quebec.

I haven’t paid the price exacted of Wolfe. (But then, no one’s built any statues of me, either.) I’ve been stoned, abused, hectored, threatened, held at gunpoint. I’ve come out of it with the kind of knowledge granted only to one of those who never expected to be loved by everyone and yet was never driven by hate–namely, an observant outsider.

The sense of being an outsider I experienced as the Last Man in London was alienating back then. But in Bethlehem and Gaza it still gives me a sense for the outsiders—whether that’s the Palestinians without their state, or the minorities who live among them, like the Christian Palestinians featured in THE COLLABORATOR OF BETHLEHEM or the few hundred Samaritans who live on a hill overlooking Nablus and are at the center of THE SAMARITAN’S SECRET. It helped me identify the people who could teach me the most about myself, to build a bond of trust with them and understand them. It also led me to write the Omar Yussef mysteries as a direct challenge to every accepted Western idea about the Palestinians.

And to every idea I ever had about me. But that’s for another blog…

During my teens, my family lived in a house in Addington, at the very farthest reach of South London. At the bottom of the hill, the road made its final exit from London. Not quite wide enough for two cars, it traveled onto the North Downs of Kent. Sometimes I would ride my bike along the lane and up a hill overlooking the Downs and lie on the grass. I was the border between London and the rest of the world. When a car went by below, I’d send out a silent message to the driver: “You just passed the last man in London.”

Much of my time was spent looking in the opposite direction, wishing we lived in central London– where things happened, where the Underground came to your neighborhood, where there was life, damn it. Where I would feel at one with those around me. Not like “the last man,” the one at the edge of everything. Like any suburban teenager, I wanted to be anywhere else in the world but where I was. And central London was both elsewhere and not impossibly far away.

Most of my friends from that time and from university, too, ended up living and working right there in central London. Perhaps they knew it was the right place for them, or maybe they never cared to ask themselves that question. I knew it wasn’t what I wanted, and I never lived there. I went down the lane that wasn’t wide enough for two cars, and I never came back. If I hadn’t, I’m sure I’d still have written. But I doubt I would have seen as much or learned what I have about myself.

The Palestinian sleuth of my crime novels Omar Yussef is, for me, a satisfying character because he represents the insights I’ve gathered in distant, eventful travels. But he’s also a measure of my ability to understand the outsiders of other cultures. Not the people journalists typically rush toward–the prime ministers and generals and imams with their false rhetoric and their stake in things staying as they are. Rather they’re the people who seem to climb the same marginal hill that I mounted as a youth and look out wondering why their world isn’t better than it is. That’s the essence of Omar Yussef (and of the best “exotic detective” fiction).

That lane near our house went up onto the Downs and undulated toward Westerham, a beautiful place built around a sloping village green. At the center of the green, there’s a statue of General Wolfe, a native of the village who led British troops to victory against the French in Canada in the Seven Years War of the mid-Eighteenth Century. The latest historical research on Wolfe suggests he was a megalomaniac glory-hunter who got exactly the kind of heroic immortality he wanted when he died at the moment of victory in Quebec.

I haven’t paid the price exacted of Wolfe. (But then, no one’s built any statues of me, either.) I’ve been stoned, abused, hectored, threatened, held at gunpoint. I’ve come out of it with the kind of knowledge granted only to one of those who never expected to be loved by everyone and yet was never driven by hate–namely, an observant outsider.

The sense of being an outsider I experienced as the Last Man in London was alienating back then. But in Bethlehem and Gaza it still gives me a sense for the outsiders—whether that’s the Palestinians without their state, or the minorities who live among them, like the Christian Palestinians featured in THE COLLABORATOR OF BETHLEHEM or the few hundred Samaritans who live on a hill overlooking Nablus and are at the center of THE SAMARITAN’S SECRET. It helped me identify the people who could teach me the most about myself, to build a bond of trust with them and understand them. It also led me to write the Omar Yussef mysteries as a direct challenge to every accepted Western idea about the Palestinians.

And to every idea I ever had about me. But that’s for another blog…

My bogus bio

Here's my latest post on the International Crime Authors Reality Check blog:

Since you’re reading this, you don’t care who I am. So I can be anyone I like. At least, that’s what somebody wrote here recently.

I posted on this blog a couple of weeks ago about Dashiell Hammett. I noted that, while a university literature student, I grew tired of all the post- structuralist and deconstructionist and Marxist esoterica I was studying. I picked up a copy of Hammett’s classic “The Maltese Falcon” and found myself transported into a gritty world, a world inhabited by real criminals, it seemed to me.

At the time, I was a real criminal. Only in the sense that I had shoplifted repeatedly (I stole books, including one by my university tutor) and indulged in proscribed intoxicants (including once with my university tutor). Not the kind of criminal Hammett revealed to me in his pages. Just a criminal, but not a bad guy.

In my recent post, I posited the idea that part of what made Hammett so good at writing about criminals was his career as a Pinkertons agent. For those not familiar with US law enforcement history, the Pinkertons were a private security agency whose men worked as detectives, but also did anti-union rough stuff, too.

This idea caught the attention of a fellow blogger who wrote that I was “romanticizing” Hammett. “Writers can toot their horn all they want,” he commented on this blog, “but an author’s bio is the least important — and least read –part of a novel for a reason.”

I think the “reason” may have less to do with readers’ lack of interest in an author’s bio than it has to do with the lack of information in the author’s bio. On a copy of a recent novel by Philip Roth, I learned in his bio that he exists only as a recipient of literary prizes (of which many were listed). He wasn’t born. He may not even write his books. He just collects prizes for them.

Nonetheless, if writers bios aren’t looked at (and are anyway not important), I plan to start including all the information about me which I’ve previously edited out. (In the past, as my novels are about the Middle East, I’ve included mainly just the facts that I was – unlike Philip Roth – born, and that subsequently I went to live and work in the Middle East, where much of what I’ve seen and heard makes its way into my books.)

Here’s my bogus new bio, which qualifies me to write about the Middle East, just as much as my previously available bio, according to some people (Note that only one fact listed below is correct. A free copy of my latest novel to the first person to identify which fact that is…):

Matt Beynon Rees was born in the George Michael Public Restroom on Rodeo Drive, Los Angeles. He was a milk monitor at kindergarten in Cardiff, Wales, until then-Education Minister Margaret Thatcher cut free milk from the schools budget, thus making five-year-old Rees the first of her four million unemployed. He graduated with a degree in finance from the Buddhist seminary at Mt. Baldie, where he minored in Leonard Cohen studies. He flew Tornado jets in the first Gulf War and was shot down over Iraq, trekking 400 miles across the desert to safety in Kuwait with nothing to drink but the urine of passing Arabs. He won Winter Olympic Bronze in the Darts Biathlon (cross country skiing with stops during which contestants must hit treble twenty and drink a lager). He was a ground-breaking radio ventriloquist on the BBC light entertainment program “Gottle of Geer,” until a producer saw his lips move and fired him. His first work of nonfiction “Get the Wife You Don’t Deserve” was an Esquire Book of the Year. He has been married six times, always to Mexican women below five feet in height (in homage to John Wayne, who did the same). He holds honorary degrees from the Mississippi State University School of Floral Management and from the Bob Jones University Department of Satanic Sociology. He lives in his house.

Since you’re reading this, you don’t care who I am. So I can be anyone I like. At least, that’s what somebody wrote here recently.

I posted on this blog a couple of weeks ago about Dashiell Hammett. I noted that, while a university literature student, I grew tired of all the post- structuralist and deconstructionist and Marxist esoterica I was studying. I picked up a copy of Hammett’s classic “The Maltese Falcon” and found myself transported into a gritty world, a world inhabited by real criminals, it seemed to me.

At the time, I was a real criminal. Only in the sense that I had shoplifted repeatedly (I stole books, including one by my university tutor) and indulged in proscribed intoxicants (including once with my university tutor). Not the kind of criminal Hammett revealed to me in his pages. Just a criminal, but not a bad guy.

In my recent post, I posited the idea that part of what made Hammett so good at writing about criminals was his career as a Pinkertons agent. For those not familiar with US law enforcement history, the Pinkertons were a private security agency whose men worked as detectives, but also did anti-union rough stuff, too.

This idea caught the attention of a fellow blogger who wrote that I was “romanticizing” Hammett. “Writers can toot their horn all they want,” he commented on this blog, “but an author’s bio is the least important — and least read –part of a novel for a reason.”

I think the “reason” may have less to do with readers’ lack of interest in an author’s bio than it has to do with the lack of information in the author’s bio. On a copy of a recent novel by Philip Roth, I learned in his bio that he exists only as a recipient of literary prizes (of which many were listed). He wasn’t born. He may not even write his books. He just collects prizes for them.

Nonetheless, if writers bios aren’t looked at (and are anyway not important), I plan to start including all the information about me which I’ve previously edited out. (In the past, as my novels are about the Middle East, I’ve included mainly just the facts that I was – unlike Philip Roth – born, and that subsequently I went to live and work in the Middle East, where much of what I’ve seen and heard makes its way into my books.)

Here’s my bogus new bio, which qualifies me to write about the Middle East, just as much as my previously available bio, according to some people (Note that only one fact listed below is correct. A free copy of my latest novel to the first person to identify which fact that is…):

Matt Beynon Rees was born in the George Michael Public Restroom on Rodeo Drive, Los Angeles. He was a milk monitor at kindergarten in Cardiff, Wales, until then-Education Minister Margaret Thatcher cut free milk from the schools budget, thus making five-year-old Rees the first of her four million unemployed. He graduated with a degree in finance from the Buddhist seminary at Mt. Baldie, where he minored in Leonard Cohen studies. He flew Tornado jets in the first Gulf War and was shot down over Iraq, trekking 400 miles across the desert to safety in Kuwait with nothing to drink but the urine of passing Arabs. He won Winter Olympic Bronze in the Darts Biathlon (cross country skiing with stops during which contestants must hit treble twenty and drink a lager). He was a ground-breaking radio ventriloquist on the BBC light entertainment program “Gottle of Geer,” until a producer saw his lips move and fired him. His first work of nonfiction “Get the Wife You Don’t Deserve” was an Esquire Book of the Year. He has been married six times, always to Mexican women below five feet in height (in homage to John Wayne, who did the same). He holds honorary degrees from the Mississippi State University School of Floral Management and from the Bob Jones University Department of Satanic Sociology. He lives in his house.

Scared away

Here's my latest post on the International Crime Authors Reality Check blog:

I keep finding new reasons why I write my novels about the Palestinians. Usually these reasons have nothing to do with the Palestinians.

Here’s the one that may be the deepest, the one I’ve known about for a while, but have only recently been able to face up to: it’s because I’m scared of home.

Not so long ago, I read the 1992 novel “Fat Lad” by Northern Irish novelist Glenn Patterson. It’s a terrific book, examining Belfast’s changing political landscape through the story of a young man returning after a decade in England.

But I was struck by my reaction to the nostalgic tone of the main character’s memories. They filled me with terror and loathing.

What were these memories? Patterson recalls Choppers, which were long-handled bikes for kids. I never had one. The main character lays out his desk with a bottle of Quink, a brand name for ink which I used at school. I wasn’t happy at school. He listens to Frankie Goes to Hollywood, a specific remix of the song Relax. Relax was number one in the charts when I was in high school; I chose to listen to music that no one else liked in high school, because I didn’t like anyone and imagined no one would like me.

I cite other examples of Patterson’s nostalgia, but I think perhaps you get the picture.

Patterson created a world coterminous with my own childhood in Wales. For Patterson, who went to England for graduate work and returned to his hometown, nostalgia is filled with warmth and friendship, even amid the violence of Belfast. Nostalgia doesn’t work if the period being viewed through rose-colored spectacles was experienced through isolation and self-loathing. I left home, and I’ve never been back.

I used to think: Never mind, everyone’s pretty miserable as a teenager. In a series of interviews with other writers on my blog, I started asking: “Do you have a pain from childhood that drives you to write?” Almost all of them responded that, No, they had pretty good childhoods. At first I refused to believe it. (I even told Miriam Froitzheim, the delightful German who gave me my copy of “Fat Lad,” that she couldn’t be a writer because she’d had a happy childhood and was a very well-balanced, happy adult. Well, I take it back, Miriam. It’s just me.)

I started to realize I had been pretty miserable in my twenties and early thirties, too. It wasn’t only my childhood. I left Britain and went to America. But I boozed myself into a different kind of isolation there, before I found my way to the Middle East.

During those early times I wrote stories of alienation – loners driven to acts of violence or victims of violence, troubled men stuck in unfulfilling relationships with doomed women. With the Palestinians, I came out of that darkness. It wasn’t just the exotic magic of their culture, their architecture, their cuisine. It was that their memories weren’t mine.

No Palestinian has ever said: Did you have a Chopper when you were a kid? Remember having those Quink-stains on your fingers at school? Did you grope your first girl dancing to Frankie at the school disco?

I’ve never had to say to a Palestinian: No, I was a miserable kid and I hate you for having been happy.

This freed me from the angst trap. Me, and my writing, both. I could enter the heads of characters who had been scarred – I understood what it was to have suffered. But they’d been scarred by war and occupation. That allowed me to see my own sufferings for what they were: bad, but things that could be overcome by personal development.

If you’re a Palestinian, you can go to therapy and meditate and listen to Mozart all you want. You’ll be better off, but you’ll still be living under occupation. In my case, life among a people with real problems helped me separate from the anger that clung to me all those years. Beside them, my life was a constant beach holiday. In Jerusalem I go for days on end without meeting anyone as relaxed as me. I’ve started to think perhaps this is the real me.

I’ve lived in the Middle East 13 years now. Last month it was 20 years since I left Britain (when I was 22.) Soon all the nostalgia novels will be about periods of British life of which I know nothing, because I was no longer living there. In the Middle East, I’ve been insulated, distant from British culture and not really immersed in Palestinian or Israeli pop culture. Free from all the babble, from the reminiscences of others’ lives which are supposed to be my shared experiences.

Free not to be a member of a broader society. Free to live inside my head. Which is good. Because that’s where novels are written.

I keep finding new reasons why I write my novels about the Palestinians. Usually these reasons have nothing to do with the Palestinians.

Here’s the one that may be the deepest, the one I’ve known about for a while, but have only recently been able to face up to: it’s because I’m scared of home.

Not so long ago, I read the 1992 novel “Fat Lad” by Northern Irish novelist Glenn Patterson. It’s a terrific book, examining Belfast’s changing political landscape through the story of a young man returning after a decade in England.

But I was struck by my reaction to the nostalgic tone of the main character’s memories. They filled me with terror and loathing.

What were these memories? Patterson recalls Choppers, which were long-handled bikes for kids. I never had one. The main character lays out his desk with a bottle of Quink, a brand name for ink which I used at school. I wasn’t happy at school. He listens to Frankie Goes to Hollywood, a specific remix of the song Relax. Relax was number one in the charts when I was in high school; I chose to listen to music that no one else liked in high school, because I didn’t like anyone and imagined no one would like me.

I cite other examples of Patterson’s nostalgia, but I think perhaps you get the picture.

Patterson created a world coterminous with my own childhood in Wales. For Patterson, who went to England for graduate work and returned to his hometown, nostalgia is filled with warmth and friendship, even amid the violence of Belfast. Nostalgia doesn’t work if the period being viewed through rose-colored spectacles was experienced through isolation and self-loathing. I left home, and I’ve never been back.

I used to think: Never mind, everyone’s pretty miserable as a teenager. In a series of interviews with other writers on my blog, I started asking: “Do you have a pain from childhood that drives you to write?” Almost all of them responded that, No, they had pretty good childhoods. At first I refused to believe it. (I even told Miriam Froitzheim, the delightful German who gave me my copy of “Fat Lad,” that she couldn’t be a writer because she’d had a happy childhood and was a very well-balanced, happy adult. Well, I take it back, Miriam. It’s just me.)

I started to realize I had been pretty miserable in my twenties and early thirties, too. It wasn’t only my childhood. I left Britain and went to America. But I boozed myself into a different kind of isolation there, before I found my way to the Middle East.

During those early times I wrote stories of alienation – loners driven to acts of violence or victims of violence, troubled men stuck in unfulfilling relationships with doomed women. With the Palestinians, I came out of that darkness. It wasn’t just the exotic magic of their culture, their architecture, their cuisine. It was that their memories weren’t mine.

No Palestinian has ever said: Did you have a Chopper when you were a kid? Remember having those Quink-stains on your fingers at school? Did you grope your first girl dancing to Frankie at the school disco?

I’ve never had to say to a Palestinian: No, I was a miserable kid and I hate you for having been happy.

This freed me from the angst trap. Me, and my writing, both. I could enter the heads of characters who had been scarred – I understood what it was to have suffered. But they’d been scarred by war and occupation. That allowed me to see my own sufferings for what they were: bad, but things that could be overcome by personal development.

If you’re a Palestinian, you can go to therapy and meditate and listen to Mozart all you want. You’ll be better off, but you’ll still be living under occupation. In my case, life among a people with real problems helped me separate from the anger that clung to me all those years. Beside them, my life was a constant beach holiday. In Jerusalem I go for days on end without meeting anyone as relaxed as me. I’ve started to think perhaps this is the real me.

I’ve lived in the Middle East 13 years now. Last month it was 20 years since I left Britain (when I was 22.) Soon all the nostalgia novels will be about periods of British life of which I know nothing, because I was no longer living there. In the Middle East, I’ve been insulated, distant from British culture and not really immersed in Palestinian or Israeli pop culture. Free from all the babble, from the reminiscences of others’ lives which are supposed to be my shared experiences.

Free not to be a member of a broader society. Free to live inside my head. Which is good. Because that’s where novels are written.

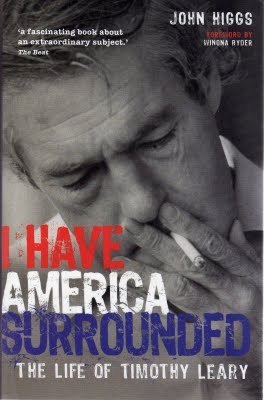

I Have Publishing Surrounded: John Higgs's Writing Life

Thomas Carlyle wrote that “A well-written life is almost as rare as a well-spent one.” There may be some debate as to whether Timothy Leary’s life was well-spent. However, his biography by John Higgs is one of the most well-written and compelling books you’ll ever come across. “I Have America Surrounded: The Life of Timothy Leary” is an alternative history of the turbulent times that made modern America. Though it’s nonfiction, it reads much like James Ellroy’s hardboiled fictionalizations of the duplicitous reality behind the 1960s and 1970s in the U.S. Once you read the book and read this interview with John Higgs, you’ll understand why he was so attracted to Leary, the scientist who saw LSD as the answer to many of society’s ills and who ended up being called the most dangerous man in America by the FBI. No, not for the drugs (though one can’t rule that out….) Rather because John, an experienced tv writer and producer, is a man who doesn’t accept the idea that things simply have to be the way they seem to others.

Do you live entirely off your writing? How many books did you write before you could make a living at it?

I don't see living entirely off writing as a realistic aspiration in the Twenty-First Century, if I'm honest. It is still possible, of course, but the publishing model is in such a state of flux that only a wild and reckless gambler would wed their future financial security to it. The most significant factor, in my view, is that the amount of writing available to the reader has increased exponentially, and a sizable percentage of that is free. That alone changes everything, and threatens the writer with smaller, more fragmented audiences at best, or obscurity at worst. However, the cultural gatekeepers are also becoming increasingly irrelevant and you no longer need permission to go out and find readers. I'm delighted by all this. I love eBook readers, Print on Demand, profit-share deals with publishers and all the rest. I can't imagine a more exciting time to be a writer.

It's not the best time to be in the publishing industry, of course, as it undergoes a slow-motion nervous breakdown. The industry operates at such a 19th Century pace that if you killed it, it wouldn’t notice for eighteen months and then it would take another year to actually get round to dying. But even so, everyone can see that major, unstoppable structural change is happening. I have a hunch that in a few years time the writer-agent-publisher relationship will be start to be replaced by a writer-manager model, with publishing, promotion and distribution farmed out on a project-by-project basis while the manager concentrates on building a long-term readership for the author.

I'm not sure that everybody is prepared to be realistic about the changes that are happening. The idea of ‘writing books’ as a profession rather than a vocation, interest or even hobby is a very romantic one and people cling to it. Writers get very angry at the idea that no-one wants them to write enough to actually give them money to do it. Painters and, to some extent, musicians and actors are generally more realistic about this than writers, and also more realistic about why they do what they do. There's no reason why writers should be above working for a living - the likes of Philip Larkin or T.S. Elliot were prepared to do so. I think a big part of this is because the idea of using writing as an excuse to lock yourself away and withdraw from the world can be very seductive.

Of course, I like money. I like people giving me money, and I especially like getting money for something that I have written. But I think the writer/reader relationship is much healthier now, now that the playing field has been leveled, and if that means authors need to hold down a day job then that's a fair price to pay.

What's a typical working day?

There's no such thing as a typical working day, just as there's no such thing as a typical person or a typical philosophy. My writing life consists mainly of trying to find little two-hour windows where I can sneak off and furiously type away, without anyone giving me a hard time for doing so. You can get a surprising amount done using this method.

Do you have a pain from childhood that compels you to write? If not, what does?

I don’t know what compels me to write, but I don’t think it’s pain from childhood. My current best guess is that I write about things in order to lose interest in them. It is those things that don’t make any sense that I have a problem with. My brain is unable to digest them and they stick around, endlessly being picked over and prodded. Writing about them is the only way I know of flushing these buggers away, leaving me clear headed and hopefully a little saner.

Other writers have other reasons for writing but I don’t claim to understand what they are. Consider writer’s block, for example; being unable to write because you have nothing that you need to say. This sounds terrific to me. Imagine all the things you could do with the time! Yet other writers insist writer's block is a terrible thing, so presumably I’m failing to understand something somewhere.

How many books did you write before you were published?

My first book was published, but then I'm a lucky beggar. That said, of course, most of the stuff I write is scrappy nonsense which is written entirely for myself and shoved away in a draw and forgotten about. Only occasionally does it amount to anything that would interest others enough to justify the process of editing, polishing and all the business stuff involved in getting it published. I'm pretty lazy and would be quite happy not to have to go through all that, but it is important to be read and to have the contents of your head peer reviewed from time to time.

Who is the greatest plotter currently writing?

I'd say Steven Moffat. TV writers tend to be better plotters than novelists or film writers – at least, the really good ones are. Novelists have too much freedom and screenwriters are too restricted by the amount of people involved and the compromises that are needed when so much money is at stake. TV writers are in a middle ground where they have to hold a general audience but can't rely on big budget spectacles, so they have to get good at either plot or character, and preferably both.

Who is the greatest stlyist currently writing?

I recently read an unpublishable novella called 'The Nabob of Bombasta' by Brian Barritt, the English beatnik who you might remember from my Timothy Leary biography. I can only describe it as like literary wasabi. It is so wild and extreme that taking a little between regular literature wipes clean your mental pallette and allows you to approach your next piece with a fresh, unprejudiced mind. It is way beyond obscene and unacceptable, but it is so good-hearted, absurd and funny that anyone who claims to be offended by it is probably lying, and probably lying to themselves. Brian quite happily describes it as utterly unpublishable yet I hear it will be published next year, on Valentine's Day. Look out for that one!

What's the weirdest idea for a book you'll never get to publish?

You can publish anything these days, no matter how weird. The only constraint is whether there is an audience big enough, or interested enough, to justify your time. But as for weirdest idea, I sometimes hanker to re-publish the Bible in wildly unsuitable fonts, to see if it retains any credibility. Who wouldn't want a copy of 'The Old Testament in Comic Sans'?

What's the best descriptive image in all of literature?

That's an easy one. The best descriptive image in all of literature - better than "He Wishes for the Cloths of Heaven" or "Rough winds do shake the darling buds of May" - is Douglas Adams' "The ships hung in the sky in much the same way that bricks don't."

Plug your latest book. What's it about? Why's it so great?

Christ no - where's the fun in that?

Affable and trim

The last couple of articles about me and my books focus on the fact that I'm rather happy. In this month's Hadassah Magazine, I'm "affable and trim." High school friends reading this on Facebook may wonder where the affability was back then...

Profile: Hadassah Magazine October 2009 Matt Beynon Rees By Leora Eren Frucht

Only gritty, dark crime fiction could evoke the corruption—and hope—in Palestinian society, believes one former foreign correspondent, now a best-selling mystery writer.

The morning sun streams through the windows that frame the Mount of Olives to the east and the hills of Bethlehem to the south. Photographs of a smiling mother and baby flash, one after the other, on a computer screen. The only sign of anything sinister in this cheerful room is the stainless-steel dagger lying in its open, velvet-trimmed case on the desk.

It is here, in this modest fifth-floor apartment in the southern Jerusalem neighborhood of San Simon, that plans for diabolical schemes of extortion, brutal torture and gruesome murders have been concocted.

With a swift motion, a tall, fair-skinned man grabs hold of the dagger. His piercing pale blue eyes sparkle with anticipation as he turns the shiny weapon slowly in his hands.

“It really is amazing,” he says with a satisfied grin, then adds, in a faint Welsh accent, “I never imagined that it would all go so well.”

Meet Matt Beynon Rees, winner of the The Crime Writers’ Association John Creasey New Blood Dagger and creator of Omar Yussef, literature’s first (and only) Palestinian detective.

Rees, a Welsh-born journalist, won the prestigious British award—an actual dagger, granted to a first-time crime novelist—for his 2007 The Collaborator of Bethlehem (Mariner), in which Yussef makes his debut.

Since then, the affable and trim Rees has cast the stocky, ex-alcoholic Yussef as the star of two more detective novels set in Gaza and Nablus respectively (A Grave in Gaza, Mariner; and The Samaritan’s Secret, Soho Press), with another—The Fourth Assassin—due out in February. The books have been published in 22 countries, earning lavish praise from critics; French daily L’Express dubbed Rees “The Dashiell Hammett of Palestine.”

The novels are more than just well-crafted whodunits. Rees uses Yussef to shine a light on Palestinian society, exposing the traditions, tensions and ties that determine how people act. The reader is led through the squalid refugee camps of Gaza, opulent palaces of corrupt Palestinian power brokers and the alleyways of Nablus’s casbah, which fill with the aroma of knafeh pastry and cardamom by day and empty out at night, when only gunmen prowl its premises. Rees paints a raw, revealing and, at times, alarming portrait of Palestinian society.

“We all think we know Palestinians, whichever stereotype we choose to ascribe to them—victims or terrorists. I want to show that we don’t know them at all,” says Rees, 42. He is sipping an espresso in the study of the apartment he shares with his American-born wife, Devorah Blachor (currently working on her first mystery novel), and their 2-year-old son, Cai (the name means “rejoice” in Welsh).

Rees grew up in a nonreligious Protestant home in Cardiff, South Wales, and says he never imagined he would end up in Jerusalem, let alone become an award-winning mystery writer and documenter of Palestinian reality. The only connection he had to the region are two great-uncles, both coal miners, who fought in General Edmund Allenby’s Imperial Camel Corps, which arrived in Jerusalem in 1917. “Both were injured,” he says. “One had his finger bitten off by a Turk. The other, whom I recall from my childhood, used to get drunk on Christmas, drop his pants and show us the scar where he got shot, in Betunia, which was near Ramallah. You could say my fascination with the region began there,” quips Rees. He pays homage to them in his second book, in which a British war cemetery in Gaza features prominently.

Like his camel-cavorting ancestors, Rees landed in Israel by chance. After studying English language and literature at Oxford, he completed a degree in journalism at the University of Maryland and covered Wall Street for five years, a period he recalls with little enthusiasm. When his American fiancée got posted as a foreign correspondent in Jerusalem, Rees joined her. The two married and subsequently divorced, with Rees remarrying a few years later. But his path was set. He, too, began working as a Jerusalem-based foreign correspondent, first for The Scotsman, then for Newsweek; in 2000, he became Middle East bureau chief for Time magazine.

If Wall Street had dulled his senses, covering the Palestinian beat heightened them: “I felt so alive, everything was so exotic to me—the sights, the sounds. I love the dirt and the dust and the way people speak to each other.”

Rees soon realized that much of what intrigued him about Palestinian society was beyond the scope of traditional journalism. But, he says, “If it didn’t mention the peace process, it wasn’t of interest to my editors.

“Most journalists are really political scientists: They want to write about the peace process and interview the prime minister,” he continues. “I don’t really care about that. I’ve always felt more like an anthropologist. I’m more interested in how people live their lives, what they eat, how their culture shapes them.” To that end, Rees learned basic Hebrew and Arabic.

“Matt has an old-fashioned reporter’s empathy that enables readers to know what his subjects are thinking—without the sheen of postmodern cynicism that characterizes so many foreign correspondents,” says Matthew Kalman, a Jerusalem-based freelance foreign correspondent who has worked with Rees. “[He:] realized early on that reporting the Palestinian-Israeli conflict is extremely superficial…. Most of the foreign media is only interested in a cowboys and Indians story.”

In 2004, Rees published a highly acclaimed nonfiction account of Israeli and Palestinian society entitled Cain’s Field: Faith, Fratricide, and Fear in the Middle East (Free Press), but felt that his effort was not adequate. “I think people want to read about the Middle East, but not in a starchy, nonfiction tone,” he notes.

Rees decided to try his hand at a novel. The Collaborator of Bethlehem was inspired by a specific incident: the cold-blooded killing of one Palestinian by another, a militia man, who accused his victim of collaborating with Israel—knowing full well that the man was innocent.

“The dirtiness of the story made me think it’s so complex that only in a novel can you get those shades of gray, in terms of people’s motivations,” says Rees, who had been dabbling in fiction since childhood. “And it had to be a crime novel because it’s a real gangster reality—not a place for a romance novel.” So, in 2006, after selling the rights to the book, Rees quit Time to write fiction full-time.

Fiction, that is, to a point. The mystery series is based, in part, on actual events and people, including Yussef, a 56-year-old history teacher at a United Nations-administered girls’ school in the Dehaisha refugee camp south of Bethlehem. The pudgy, often breathless grandfather (whose favorite granddaughter builds him a Web site for The Palestine Agency for Detection) is no suave sleuth, but a kind of accidental hero. Driven by a deep sense of integrity, he seeks the truth and tries to fight growing corruption and violence in the West Bank and Gaza Strip—often at considerable personal risk.

“Yussef is based on a friend who lives in Dehaisha refugee camp whom I have known for over 10 years,” says Rees. “He is very much like the character in the book—quite acerbic and very intelligent. He gets very frustrated seeing how corruption and criminality are destroying a society that he loves very much.”

Are there many Omar Yussefs in Palestinian society?

“There are many who have the same basic discontents about the corruption and violence,” he says, “but there are not that many who take action because most feel trapped.” In a telling example of this, in one novel, a man who protests the use of his rooftop to shoot at Israelis meets an untimely fate. “But there are Palestinians who are trying to change things in very small ways,” Rees continues, adding a note of optimism: “I made Omar a teacher because he represents the possibility that the next generation will be different.”

Jamil Hamad, Time’s veteran Palestinian correspondent, says that several Palestinians have shared with him their respect for Rees’s depiction of their society. “I have received calls from other Palestinians here,” Hamad says, “and from Arabs in Jordan, Syria, Egypt and North Africa who say they are very grateful to him for painting a realistic portrait of Palestinians and are proud of the books.”

Yussef’s adversaries—ruthless heads of militias and security forces, weapons smugglers and crooked politicians—make for a colorful cast of bad guys based on real people whom Rees got to know while researching his novels and during his journalistic days. Military Intelligence Chief General Husseini, a character in A Grave in Gaza, is renowned for his particular method of torture: slicing off the tips of prisoners’ fingers. The person and method are real, though the name given to the style of torture—a Husseini manicure—is Rees’s invention.

In researching the novels, Rees spent entire days and nights hanging out with gunmen, most of whom have since been killed—either by Israeli forces or by other Palestinians. Nearly all of them lived with the knowledge that a violent death was imminent.

“It is almost as though they are ghosts when they are alive,” he says. “It feels eerie to have met someone who was as good as dead anyway.”

And because his sinister types are based on portraits of real individuals, he believes that he is able to present complex, nuanced antagonists, rather than cartoon “bad guys.”

“I feel like if you’re a writer and you can ‘know the minds of many men,’ you can tell their story as though it was emerging from your own emotions,” explains Rees, quoting The Odyssey.

“When I was in a refugee camp in the middle of the night, talking to people from Hamas and Fatah who expected to die at any moment, I think I got some insight into the minds of many men,” concludes Rees, whose neutral foreign looks and identity helped him gain access to his subjects and win their trust.

“I think through these novels he is reporting the conflict in a different and exceptional way,” says Hamad. “He’s not just writing a novel—he’s reporting the story. Matt is one of the few journalists I work with who is always capable of ‘digesting’ it properly, meaning he has no illusions.”

Rees’s literary heroes are the classic detective writers Raymond Chandler and Dashiell Hammett. “I love the gritty realism, but I also love the way in which Chandler writes,” he says. “I think he is the greatest stylist of American literature.”

That gritty realism is a hallmark of the Omar Yussef series, which is littered with corpses but also boasts more subtle touches like a swarm of flies that follows the protagonist throughout his sojourn through the filth—both material and moral—of Gaza.

Rees’s own life is a sharp contrast from that of his characters. Every morning, he does a few yoga stretches and writes standing up for several hours at his raised computer terminal. He swims, works out, does Pilates and meditation. He also plays bass in a local band and delights in his toddler son. “I feel younger all the time,” he says happily. He is currently learning piano as part of the research for his new historical novel that evolves around the musical scene in 19th-century Vienna. “I needed a short break from Omar Yussef to refresh myself,” he says.

In The Fourth Assassin (Soho Press), Rees set the action in Bay Ridge, Brooklyn, an area with a growing expatriate Palestinian community, to help American readers “understand the reality of the Muslim minorities living among them.”

A fifth novel will probably unfold in the Old City of Jerusalem and will be the first to include Israeli characters. Rees purposely kept Israelis out of the previous books in which the numerous instances of kidnapping, extortion and murder are almost all committed by Palestinians against other Palestinians. “Part of my goal is to show it is not enough for the Palestinians to say ‘We’re the victims,’” he says. “Palestinians have to take some responsibility. That is what Omar Yussef stands for. When the police won’t solve a murder, Yussef feels he has to do it.”

How long can the series go on? “As long as the publishers want more,” he says, smiling hopefully. “I would like to take Omar throughout the Arab world.

“It’s not difficult to come up with the stories,” he continues. “Palestinians keep giving me material by killing each other and by moving from one disaster to another,” he adds, sounding much like his ever-acerbic but still optimistic Omar Yussef.

Profile: Hadassah Magazine October 2009 Matt Beynon Rees By Leora Eren Frucht

Only gritty, dark crime fiction could evoke the corruption—and hope—in Palestinian society, believes one former foreign correspondent, now a best-selling mystery writer.

The morning sun streams through the windows that frame the Mount of Olives to the east and the hills of Bethlehem to the south. Photographs of a smiling mother and baby flash, one after the other, on a computer screen. The only sign of anything sinister in this cheerful room is the stainless-steel dagger lying in its open, velvet-trimmed case on the desk.

It is here, in this modest fifth-floor apartment in the southern Jerusalem neighborhood of San Simon, that plans for diabolical schemes of extortion, brutal torture and gruesome murders have been concocted.

With a swift motion, a tall, fair-skinned man grabs hold of the dagger. His piercing pale blue eyes sparkle with anticipation as he turns the shiny weapon slowly in his hands.

“It really is amazing,” he says with a satisfied grin, then adds, in a faint Welsh accent, “I never imagined that it would all go so well.”

Meet Matt Beynon Rees, winner of the The Crime Writers’ Association John Creasey New Blood Dagger and creator of Omar Yussef, literature’s first (and only) Palestinian detective.

Rees, a Welsh-born journalist, won the prestigious British award—an actual dagger, granted to a first-time crime novelist—for his 2007 The Collaborator of Bethlehem (Mariner), in which Yussef makes his debut.

Since then, the affable and trim Rees has cast the stocky, ex-alcoholic Yussef as the star of two more detective novels set in Gaza and Nablus respectively (A Grave in Gaza, Mariner; and The Samaritan’s Secret, Soho Press), with another—The Fourth Assassin—due out in February. The books have been published in 22 countries, earning lavish praise from critics; French daily L’Express dubbed Rees “The Dashiell Hammett of Palestine.”

The novels are more than just well-crafted whodunits. Rees uses Yussef to shine a light on Palestinian society, exposing the traditions, tensions and ties that determine how people act. The reader is led through the squalid refugee camps of Gaza, opulent palaces of corrupt Palestinian power brokers and the alleyways of Nablus’s casbah, which fill with the aroma of knafeh pastry and cardamom by day and empty out at night, when only gunmen prowl its premises. Rees paints a raw, revealing and, at times, alarming portrait of Palestinian society.

“We all think we know Palestinians, whichever stereotype we choose to ascribe to them—victims or terrorists. I want to show that we don’t know them at all,” says Rees, 42. He is sipping an espresso in the study of the apartment he shares with his American-born wife, Devorah Blachor (currently working on her first mystery novel), and their 2-year-old son, Cai (the name means “rejoice” in Welsh).

Rees grew up in a nonreligious Protestant home in Cardiff, South Wales, and says he never imagined he would end up in Jerusalem, let alone become an award-winning mystery writer and documenter of Palestinian reality. The only connection he had to the region are two great-uncles, both coal miners, who fought in General Edmund Allenby’s Imperial Camel Corps, which arrived in Jerusalem in 1917. “Both were injured,” he says. “One had his finger bitten off by a Turk. The other, whom I recall from my childhood, used to get drunk on Christmas, drop his pants and show us the scar where he got shot, in Betunia, which was near Ramallah. You could say my fascination with the region began there,” quips Rees. He pays homage to them in his second book, in which a British war cemetery in Gaza features prominently.

Like his camel-cavorting ancestors, Rees landed in Israel by chance. After studying English language and literature at Oxford, he completed a degree in journalism at the University of Maryland and covered Wall Street for five years, a period he recalls with little enthusiasm. When his American fiancée got posted as a foreign correspondent in Jerusalem, Rees joined her. The two married and subsequently divorced, with Rees remarrying a few years later. But his path was set. He, too, began working as a Jerusalem-based foreign correspondent, first for The Scotsman, then for Newsweek; in 2000, he became Middle East bureau chief for Time magazine.

If Wall Street had dulled his senses, covering the Palestinian beat heightened them: “I felt so alive, everything was so exotic to me—the sights, the sounds. I love the dirt and the dust and the way people speak to each other.”

Rees soon realized that much of what intrigued him about Palestinian society was beyond the scope of traditional journalism. But, he says, “If it didn’t mention the peace process, it wasn’t of interest to my editors.

“Most journalists are really political scientists: They want to write about the peace process and interview the prime minister,” he continues. “I don’t really care about that. I’ve always felt more like an anthropologist. I’m more interested in how people live their lives, what they eat, how their culture shapes them.” To that end, Rees learned basic Hebrew and Arabic.

“Matt has an old-fashioned reporter’s empathy that enables readers to know what his subjects are thinking—without the sheen of postmodern cynicism that characterizes so many foreign correspondents,” says Matthew Kalman, a Jerusalem-based freelance foreign correspondent who has worked with Rees. “[He:] realized early on that reporting the Palestinian-Israeli conflict is extremely superficial…. Most of the foreign media is only interested in a cowboys and Indians story.”

In 2004, Rees published a highly acclaimed nonfiction account of Israeli and Palestinian society entitled Cain’s Field: Faith, Fratricide, and Fear in the Middle East (Free Press), but felt that his effort was not adequate. “I think people want to read about the Middle East, but not in a starchy, nonfiction tone,” he notes.

Rees decided to try his hand at a novel. The Collaborator of Bethlehem was inspired by a specific incident: the cold-blooded killing of one Palestinian by another, a militia man, who accused his victim of collaborating with Israel—knowing full well that the man was innocent.

“The dirtiness of the story made me think it’s so complex that only in a novel can you get those shades of gray, in terms of people’s motivations,” says Rees, who had been dabbling in fiction since childhood. “And it had to be a crime novel because it’s a real gangster reality—not a place for a romance novel.” So, in 2006, after selling the rights to the book, Rees quit Time to write fiction full-time.

Fiction, that is, to a point. The mystery series is based, in part, on actual events and people, including Yussef, a 56-year-old history teacher at a United Nations-administered girls’ school in the Dehaisha refugee camp south of Bethlehem. The pudgy, often breathless grandfather (whose favorite granddaughter builds him a Web site for The Palestine Agency for Detection) is no suave sleuth, but a kind of accidental hero. Driven by a deep sense of integrity, he seeks the truth and tries to fight growing corruption and violence in the West Bank and Gaza Strip—often at considerable personal risk.

“Yussef is based on a friend who lives in Dehaisha refugee camp whom I have known for over 10 years,” says Rees. “He is very much like the character in the book—quite acerbic and very intelligent. He gets very frustrated seeing how corruption and criminality are destroying a society that he loves very much.”

Are there many Omar Yussefs in Palestinian society?

“There are many who have the same basic discontents about the corruption and violence,” he says, “but there are not that many who take action because most feel trapped.” In a telling example of this, in one novel, a man who protests the use of his rooftop to shoot at Israelis meets an untimely fate. “But there are Palestinians who are trying to change things in very small ways,” Rees continues, adding a note of optimism: “I made Omar a teacher because he represents the possibility that the next generation will be different.”

Jamil Hamad, Time’s veteran Palestinian correspondent, says that several Palestinians have shared with him their respect for Rees’s depiction of their society. “I have received calls from other Palestinians here,” Hamad says, “and from Arabs in Jordan, Syria, Egypt and North Africa who say they are very grateful to him for painting a realistic portrait of Palestinians and are proud of the books.”

Yussef’s adversaries—ruthless heads of militias and security forces, weapons smugglers and crooked politicians—make for a colorful cast of bad guys based on real people whom Rees got to know while researching his novels and during his journalistic days. Military Intelligence Chief General Husseini, a character in A Grave in Gaza, is renowned for his particular method of torture: slicing off the tips of prisoners’ fingers. The person and method are real, though the name given to the style of torture—a Husseini manicure—is Rees’s invention.

In researching the novels, Rees spent entire days and nights hanging out with gunmen, most of whom have since been killed—either by Israeli forces or by other Palestinians. Nearly all of them lived with the knowledge that a violent death was imminent.

“It is almost as though they are ghosts when they are alive,” he says. “It feels eerie to have met someone who was as good as dead anyway.”

And because his sinister types are based on portraits of real individuals, he believes that he is able to present complex, nuanced antagonists, rather than cartoon “bad guys.”

“I feel like if you’re a writer and you can ‘know the minds of many men,’ you can tell their story as though it was emerging from your own emotions,” explains Rees, quoting The Odyssey.

“When I was in a refugee camp in the middle of the night, talking to people from Hamas and Fatah who expected to die at any moment, I think I got some insight into the minds of many men,” concludes Rees, whose neutral foreign looks and identity helped him gain access to his subjects and win their trust.

“I think through these novels he is reporting the conflict in a different and exceptional way,” says Hamad. “He’s not just writing a novel—he’s reporting the story. Matt is one of the few journalists I work with who is always capable of ‘digesting’ it properly, meaning he has no illusions.”

Rees’s literary heroes are the classic detective writers Raymond Chandler and Dashiell Hammett. “I love the gritty realism, but I also love the way in which Chandler writes,” he says. “I think he is the greatest stylist of American literature.”

That gritty realism is a hallmark of the Omar Yussef series, which is littered with corpses but also boasts more subtle touches like a swarm of flies that follows the protagonist throughout his sojourn through the filth—both material and moral—of Gaza.

Rees’s own life is a sharp contrast from that of his characters. Every morning, he does a few yoga stretches and writes standing up for several hours at his raised computer terminal. He swims, works out, does Pilates and meditation. He also plays bass in a local band and delights in his toddler son. “I feel younger all the time,” he says happily. He is currently learning piano as part of the research for his new historical novel that evolves around the musical scene in 19th-century Vienna. “I needed a short break from Omar Yussef to refresh myself,” he says.

In The Fourth Assassin (Soho Press), Rees set the action in Bay Ridge, Brooklyn, an area with a growing expatriate Palestinian community, to help American readers “understand the reality of the Muslim minorities living among them.”

A fifth novel will probably unfold in the Old City of Jerusalem and will be the first to include Israeli characters. Rees purposely kept Israelis out of the previous books in which the numerous instances of kidnapping, extortion and murder are almost all committed by Palestinians against other Palestinians. “Part of my goal is to show it is not enough for the Palestinians to say ‘We’re the victims,’” he says. “Palestinians have to take some responsibility. That is what Omar Yussef stands for. When the police won’t solve a murder, Yussef feels he has to do it.”

How long can the series go on? “As long as the publishers want more,” he says, smiling hopefully. “I would like to take Omar throughout the Arab world.

“It’s not difficult to come up with the stories,” he continues. “Palestinians keep giving me material by killing each other and by moving from one disaster to another,” he adds, sounding much like his ever-acerbic but still optimistic Omar Yussef.

That's my boy

I started to feel recently that my bio on www.mattbeynonrees.com was a bit over-serious. First of all, it was in the third person. I honestly never refer to myself in the third person (except when I'm shopping and I ask my wife "Would Matt Beynon Rees wear a shirt in this shade of pink?") Then I saw that the bio took my writing and -- worse still -- me, rather seriously. I prefer to make it clear that I can laugh at myself. So I changed the whole bio, adding some tidbits of my past which wouldn't make it onto a bio of the "He is the recipient of a Peepgass Fellowship for the Arts and divides his time between Bal Harbor and East 74th Street" type. Here's how it turned out:

Matt Beynon Rees

WHERE: I live in Jerusalem. I came here in 1996. For love. Then we divorced. But the place took hold. Not for the violence and the excitement that sometimes surrounds it, but because I saw people in extreme situations. Through the emotions they experienced, I came to understand myself.

BEFORE THE WRITING: There was never really a time before I wrote. I’ve been at it since I was seven (a poem about a tree, on the classroom wall with a gold star beside it.) But I arrived in the Middle East as a journalist with only a couple of published short stories to my name. First I wrote for The Scotsman, then Newsweek, and from 2000 until 2006 as Time Magazine’s Jerusalem bureau chief. I won some awards for covering the intifada. Yasser Arafat once tried to have me arrested, but I eluded him and decided to focus on fiction. I’d learned so much about the Palestinians – and about life – that didn’t fit into the limited world of journalism. So I wrote my Palestinian crime novels.

BEFORE JERUSALEM: I was born in Newport, Wales, in 1967. That’s my mother’s hometown; my father’s from Maesteg in the Llynfi valley. We moved around, to Cardiff and Croydon, then I studied English at Wadham College, Oxford University with Terry Eagleton as my tutor. Contemporaries may remember me as the fellow with bleached blonde hair at the bar of the King’s Arms in the company of the Irish porters from All Souls College. I did an MA at the University of Maryland and lived in New York for five years before I hit the Middle East.

WHERE THE BOOKS CAME FROM: I wrote a nonfiction account of Israeli and Palestinian society called Cain's Field: Faith, Fratricide, and Fear in the Middle East in 2004 (Free Press). I’m proud of it, because it really gets to the heart of the conflict here – it isn’t one of those notebook-dump foreign correspondent books.

I was looking for my next project and came up with the idea for Omar Yussef, my Palestinian sleuth, while chatting with my wife in our favorite hotel, the Ponte Sisto in the Campo de’Fiori in Rome. I realized I had become friends with many colorful Palestinians who’d given me insights into the dark side of their society. Like the former Mister Palestine (he dead-lifts 900 pounds), a one-time bodyguard to Yasser Arafat (skilled in torture), and a delightful fellow who was a hitman for Arafat during the 1980s. To tell the true-life stories I’d amassed over a decade, I decided to channel the reporting into a crime series. After all, Palestine’s reality is no romance novel.

THE NOVELS: The first novel, The Collaborator of Bethlehem (UK title The Bethlehem Murders), was published in February 2007 by Soho Press. In the UK it won the prestigious Crime Writers Association John Creasey Dagger in 2008, and was nominated in the US for the Barry First Novel Award, the Macavity First Mystery Award, and the Quill Best Mystery Award. In France it’s been shortlisted for the Prix des Lecteurs. New York Times reviewer Marilyn Stasio called it “an astonishing first novel.” It was named one of the Top 10 Mysteries of the Year by Booklist and, in the UK Sir David Hare made it his Book of the Year in The Guardian.

Colin Dexter, author of the Inspector Morse novels, called Omar Yussef “a splendid creation.” Omar was called “Philip Marlowe fed on hummus” by one reviewer and “Yasser Arafat meets Miss Marple” by another.

The second book in the series, A Grave in Gaza, appeared in February 2008 (and at the same time under the title The Saladin Murders in the UK). The Bookseller calls it “a cracking, atmospheric read.” I put in elements of the plot relating to British military cemeteries in Gaza in homage to my two great uncles, who rode through there with the Imperial Camel Corps in 1917. One of them, Uncle Dai Beynon, was still around when I was a boy, and I was named after him.

The third book in the series, The Samaritan’s Secret, was published in February 2009. The New York Times said it was “provocative” and it had great reviews in places I’d not have expected – The Sowetan, the newspaper of that S. African township, for example.

AROUND THE WORLD: My Omar Yussef Mystery series has been sold to leading publishers in 22 countries: the U.S., France, Italy, Britain, Poland, Spain, Germany, Holland, Israel, Portugal, Brazil, Norway, Denmark, the Czech Republic, Romania, Sweden, Iceland, Chile, Venezuela, Japan, Indonesia and Greece.

OMAR’S NEXT TRAVELS: THE FOURTH ASSASSIN, the fourth novel in my series, will be published in February 2010. In it, Omar visits the famous Palestinian town of Brooklyn, New York (there really is a growing community there in Bay Ridge), and finds a dead body in his son’s bed…

REACH ME AT: matt@mattbeynonrees.com.

Matt Beynon Rees

WHERE: I live in Jerusalem. I came here in 1996. For love. Then we divorced. But the place took hold. Not for the violence and the excitement that sometimes surrounds it, but because I saw people in extreme situations. Through the emotions they experienced, I came to understand myself.

BEFORE THE WRITING: There was never really a time before I wrote. I’ve been at it since I was seven (a poem about a tree, on the classroom wall with a gold star beside it.) But I arrived in the Middle East as a journalist with only a couple of published short stories to my name. First I wrote for The Scotsman, then Newsweek, and from 2000 until 2006 as Time Magazine’s Jerusalem bureau chief. I won some awards for covering the intifada. Yasser Arafat once tried to have me arrested, but I eluded him and decided to focus on fiction. I’d learned so much about the Palestinians – and about life – that didn’t fit into the limited world of journalism. So I wrote my Palestinian crime novels.

BEFORE JERUSALEM: I was born in Newport, Wales, in 1967. That’s my mother’s hometown; my father’s from Maesteg in the Llynfi valley. We moved around, to Cardiff and Croydon, then I studied English at Wadham College, Oxford University with Terry Eagleton as my tutor. Contemporaries may remember me as the fellow with bleached blonde hair at the bar of the King’s Arms in the company of the Irish porters from All Souls College. I did an MA at the University of Maryland and lived in New York for five years before I hit the Middle East.

WHERE THE BOOKS CAME FROM: I wrote a nonfiction account of Israeli and Palestinian society called Cain's Field: Faith, Fratricide, and Fear in the Middle East in 2004 (Free Press). I’m proud of it, because it really gets to the heart of the conflict here – it isn’t one of those notebook-dump foreign correspondent books.

I was looking for my next project and came up with the idea for Omar Yussef, my Palestinian sleuth, while chatting with my wife in our favorite hotel, the Ponte Sisto in the Campo de’Fiori in Rome. I realized I had become friends with many colorful Palestinians who’d given me insights into the dark side of their society. Like the former Mister Palestine (he dead-lifts 900 pounds), a one-time bodyguard to Yasser Arafat (skilled in torture), and a delightful fellow who was a hitman for Arafat during the 1980s. To tell the true-life stories I’d amassed over a decade, I decided to channel the reporting into a crime series. After all, Palestine’s reality is no romance novel.

THE NOVELS: The first novel, The Collaborator of Bethlehem (UK title The Bethlehem Murders), was published in February 2007 by Soho Press. In the UK it won the prestigious Crime Writers Association John Creasey Dagger in 2008, and was nominated in the US for the Barry First Novel Award, the Macavity First Mystery Award, and the Quill Best Mystery Award. In France it’s been shortlisted for the Prix des Lecteurs. New York Times reviewer Marilyn Stasio called it “an astonishing first novel.” It was named one of the Top 10 Mysteries of the Year by Booklist and, in the UK Sir David Hare made it his Book of the Year in The Guardian.

Colin Dexter, author of the Inspector Morse novels, called Omar Yussef “a splendid creation.” Omar was called “Philip Marlowe fed on hummus” by one reviewer and “Yasser Arafat meets Miss Marple” by another.

The second book in the series, A Grave in Gaza, appeared in February 2008 (and at the same time under the title The Saladin Murders in the UK). The Bookseller calls it “a cracking, atmospheric read.” I put in elements of the plot relating to British military cemeteries in Gaza in homage to my two great uncles, who rode through there with the Imperial Camel Corps in 1917. One of them, Uncle Dai Beynon, was still around when I was a boy, and I was named after him.

The third book in the series, The Samaritan’s Secret, was published in February 2009. The New York Times said it was “provocative” and it had great reviews in places I’d not have expected – The Sowetan, the newspaper of that S. African township, for example.

AROUND THE WORLD: My Omar Yussef Mystery series has been sold to leading publishers in 22 countries: the U.S., France, Italy, Britain, Poland, Spain, Germany, Holland, Israel, Portugal, Brazil, Norway, Denmark, the Czech Republic, Romania, Sweden, Iceland, Chile, Venezuela, Japan, Indonesia and Greece.

OMAR’S NEXT TRAVELS: THE FOURTH ASSASSIN, the fourth novel in my series, will be published in February 2010. In it, Omar visits the famous Palestinian town of Brooklyn, New York (there really is a growing community there in Bay Ridge), and finds a dead body in his son’s bed…

REACH ME AT: matt@mattbeynonrees.com.

In your face Tom Jones: I'm a Welsh icon

Welsh Icons ("an Encyclopedia and Gazetteer of Wales and all Things Welsh - A Cymrupedia if you like."...uh, "Cymru" being the Welsh word for Wales.) lists me among the "iconic" writers on its site. That puts me in the company of thriller king Ken Follett, sinister Willy Wonka-man Roald Dahl, and upright role model Dylan Thomas. Diolch yn fawr, as we say in Wales when we mean to say "thanks very much." My wife nearly choked on her bagel when I told her, but then she added: "Sure, you're an icon." New York sarcasm.

The listing is, of course, a great follow-up to my mother's recent phone call in which she informed me that one of her friends in her pottery class found my name on Wikipedia's notable people from Newport list, that being my home town in South Wales. I'm right there between Johnny Morris (who, for those reading in the US, hosted a British children's show about animals) and Michael Sheen, the actor famous for playing Tony Blair and David Frost. (Further down the list: rappers Goldie Lookin' Chain and King Arthur's sixth-century pal St. Cadoc.)

Anyway, from Jerusalem (which is rather full of actual icons and much too "iconic" for its own good) I wish you a happy new year: Blwyddwyn Newydd Dda!

(In case you're wondering why "Wales" isn't Welsh for Wales. "Wales" is derived from the Old English, that is Saxon, word for foreigners. Because when the Saxons came over from Germany, the so-called foreigners were living in what's now England. But that's water under the bridge...Twll din pob Sais! I add that with a touch of my wife's New York sarcasm and not to be taken seriously...)

Meet Nutanyahu: New ebook shows why Israeli PM wants to fail

The new ebook from my alternative news venture DeltaFourth. It draws on many meetings with Bibi over a decade and a half, and comes to very unconventional conclusions.

PSYCHOBIBI: Who is Israel’s Prime Minister and Why Does He Want to Fail?

The shocking, hilarious, innovative new ebook from D4.

Benjamin Netanyahu, the man often portrayed as an extremist, is really just locked in a deep psychological battle with the ghosts of his tough father and golden brother. The result: Bibi’s driven to succeed, so long as he can always get it wrong in the end. Confused? You won’t be. Not after you’ve met Psychobibi. Hard-hitting and irreverent, incisive and hardboiled, D4 eviscerates the myth behind the man they love to hate.

Special $2.99 price on amazon.com, or the equivalent in your local currency.

Published on March 17, 2013 00:48

•

Tags:

bibi, biography, middle-east, netanyahu, politics, psychobibi, psychology

Psychobibi: Neurotic King of Israel

Like Barack Obama, who's in Israel now for some chinwagging, I've met Bibi Netanyahu many times. Like Barack Obama, I know that there's something almost unfathomably complex going on inside the man's head. By the end of his trip to Israel, Barack Obama might be ready to write a book called PSYCHOBIBI. Unfortunately for him, I got there first.

Like Barack Obama, who's in Israel now for some chinwagging, I've met Bibi Netanyahu many times. Like Barack Obama, I know that there's something almost unfathomably complex going on inside the man's head. By the end of his trip to Israel, Barack Obama might be ready to write a book called PSYCHOBIBI. Unfortunately for him, I got there first.In PSYCHOBIBI I write with Matthew Kalman about the psychological struggles behind the Israeli leader's self-destructivenes. We get deep inside Bibi's psyche by using telling moments from our many meetings with him over the years. Here's an example that didn't make it into the ebook:

I once spent a day with Bibi touring polling stations on election day. It was the typical compact between a politician and a journalist. The journalist gets access; the politician gets covered, gets publicity. Bibi gave me that. But in the style to which I've become accustomed, he undercut himself.

At the end of the day, we went to a memorial service for his mother. We picked up his wife and sons en route. At the service, my photographer had them pose, offering to take a family picture to send along to Bibi. As he gathered his wife and children around him, Bibi said: "Come on. Let's get something out of all this."

As if the politician-journalist compact didn't exist. Or was beneath him.

I didn't care. But there are plenty of journalists who'd have felt scorned or humiliated by the breaking of the compact. Because if the one side thinks it's not getting anything (or says so), then it makes the journalist a cynical user. (Which we are, but we don't like to be confronted with it.) Of course, the real reason was that he had to hit out at someone because he was about to meet his father. That's a factor at the heart of Psychobibi...

The man I call Psychobibi does this kind of thing all the time in his political life, too. It colors his diplomacy and his interactions with other Israeli politicians and international figures. In PSYCHOBIBI, we show exactly why Bibi does it.

Published on March 21, 2013 04:00

•

Tags:

biography, diplomacy, israel, jewish-history, middle-east, netanyahu, politics

Salon: Check out 'Psychobibi'

A great piece on Salon.com highlighting the relationship between the two Bs, Bibi and Barack cites my new ebook

PSYCHOBIBI

: Who is Israel's Prime Minister and Why Does He Want to Fail?: "Netanyahu’s often clumsy outreach to the United States and his image, in Israel, as a complex figure with a dark and possibly unfathomable mind is the subject of a new book, PSYCHOBIBI."

Published on April 04, 2013 01:41

•

Tags:

barack-obama, biography, israel, middle-east, netanyahu, palestinians