Matt Rees's Blog - Posts Tagged "austria"

Bruno in Jerusalem

It's hard enough to get around the notorious Ein el-Hilweh Refugee Camp in Lebanon at the best of times. I can testify to that, having had a few sweaty-palmed visits to the place myself to interview the hardline Palestinian gunmen who rule the camp. Try doing it after calling on the head of the Aqsa Martyrs Brigades to eschew beards which "don't look good on your King Osama" and while dressed as "Austria's greatest gay superstar since Schwarzennegger."

But then we know that Sacha Baron Cohen's alter ego Bruno has balls of steel--because we see them being wrenched about by a dust-buster in such a way that flesh and blood genitalia wouldn't be able to handle.

Baron Cohen's movie is out this week in the Middle East. The segment shot in Jerusalem got a big laugh at the local theater where I saw the film last night. Baron Cohen minces through an ultra-Orthodox neighborhood dressed as a sexy Hassid (probably a first), and engages in a debate with a former Palestinian government minister and an ex-Mossad official in which he confuses Hamas and hummus. "I mean, why is Hamas so dangerous? It's just beans, right?"

It wasn't one of the Middle Eastern segments that scored highest with the Israeli audience, however. When Bruno is running down a list of Hollywood stars he wants in his putative talkshow, he's told that "Stevie Wunderbar" and "Bradolph Pittler" have turned him down.

Refusing to give up, he points hopefully at a picture of Mel Gibson and asks: "Der Fuehrer?" Proving that Gibson's drunken antisemitic rant to a traffic cop is more famous than Braveheart, that one got a round of applause in the theater.

But then we know that Sacha Baron Cohen's alter ego Bruno has balls of steel--because we see them being wrenched about by a dust-buster in such a way that flesh and blood genitalia wouldn't be able to handle.

Baron Cohen's movie is out this week in the Middle East. The segment shot in Jerusalem got a big laugh at the local theater where I saw the film last night. Baron Cohen minces through an ultra-Orthodox neighborhood dressed as a sexy Hassid (probably a first), and engages in a debate with a former Palestinian government minister and an ex-Mossad official in which he confuses Hamas and hummus. "I mean, why is Hamas so dangerous? It's just beans, right?"

It wasn't one of the Middle Eastern segments that scored highest with the Israeli audience, however. When Bruno is running down a list of Hollywood stars he wants in his putative talkshow, he's told that "Stevie Wunderbar" and "Bradolph Pittler" have turned him down.

Refusing to give up, he points hopefully at a picture of Mel Gibson and asks: "Der Fuehrer?" Proving that Gibson's drunken antisemitic rant to a traffic cop is more famous than Braveheart, that one got a round of applause in the theater.

My latest culture clash

Here's my latest post on the International Crime Authors Reality Check blog:

The Austrian Hospice of the Holy Family is a beautiful sandstone building on the corner where the Via Dolorosa turns briefly onto the main alley of the Muslim Quarter’s souq. Buzz at the main gate, climb up two flights of enclosed steps, and you’re in a palm-shaded garden fronting a broad, four-story façade. Nearly 150 years old, it was built for Catholic pilgrims and for much of the second half of the last century was an insanitary hospital. Now returned to its original Austrian owners, it’s a hotel for church groups visiting the historic sites of Jerusalem.

From its roof, there’s a panoramic view of the Old City. It’s for this that I labored up the front steps with my friend, videographer David Blumenfeld, and his numerous camera bags, lights and reflector shields, last month. We’d already filmed a promo video for my next novel THE FOURTH ASSASSIN in my favorite seedy Old City café, where I shone with sweat, swallowed cardamom-flavored coffee and sucked on a foul nargila, until I looked sufficiently like an inveterate marijuana-user coming down. Now it was time for a second video.

I approached the front desk of the Hospice in the large marble entrance hall. A blonde man in his twenties greeted me: “Grüss Gott.” I’m a lover of things Austrian, so I had a good feeling already.

“Grüss Gott. We’re making a short video for my website. Can we film on the roof?”

“It’s not allowed, unless you have permission.” Not unfriendly. Just stating the rules.

But I’ve lived in the Middle East long enough to know that there ARE no rules. “Don’t worry. It’s really nothing. It’s just for my website. To tell people about my book.”

“What is the book?”

The truth: It’s about a Palestinian teacher who goes to visit his son in New York and discovers a headless body in his son’s bed. No, I’d better not tell him that. It doesn’t sound like something he’d want a pilgrim hostel associated with. How about this? “It’s about Palestinians and how they live their lives.”

A bit more of this and the Austrian was thinking hard. “Ok, but just for ten minutes.”

“Of course, thank you. That’s very kind of you. Ten minutes, of course.” In the Middle East, one of the things that really gets me down is that putting one over on someone else isn’t seen as a bad thing to do. If you can get away with it, then good for you. Naturally when I get the opportunity to do this, I have a feeling of payback for all the times I’ve been deliberately misled by the locals. With that warm sensation, I ascended in the Hospice’s rickety elevator.

Up on the roof, the afternoon sunshine was too bright to film. It was so harsh I’d have been squinting into the camera like Clint Eastwood. So David and I descended to the Hospice’s garden café. For a mere 100 shekels ($30) we had a slice each of strudel (an uncommon dish in Jerusalem, where even Israelis who arrived as immigrants from Austria tend to eat Middle Eastern style), some soda and coffee.

Suitably refreshed we returned to the roof and soldiered on, despite the insanely bright sunshine.

Despite the occasional loud Israeli on a cellphone and the Korean tourists who stopped taking photos of the Dome of the Rock so they could photograph me, I managed to read most of the first chapter of THE FOURTH ASSASSIN without a pause.

Then, just before I’d finished, from the corner of my eye I spy the blonde fellow from reception striding toward me.

“Sir, you have to stop now. This has been more than 10 minutes,” he said.

“We’ve only been working a few minutes. We were down in the café most of the time. We had strudel.”

He twisted his face as though his finger had just gone through the toilet paper. “And I should believe you?”

“Yes, why would I lie? Go and ask the people in the coffee shop.”

I feel for this Austrian. After all, Israelis and Palestinians are able to lie with absolutely no compunction. It’s one of the first things you learn when you live here a while. I could see that this poor fellow had been at the front desk of the Hospice for a sufficient time to train him to recognize a lie, but not long enough to give him the graceful Arab ability to maneuver around someone else’s untruths without humiliating them. This fellow had only two options: let me get away with it, or kick me out.

“So five more minutes and then you’re out,” he said.

Here’s where my own cultural training came in. The over-emotional Welshman in me wanted to say: Listen, butty, I paid 100 shekels for some stiff strudel in your café, so you can bloody well calm down. In any case what do you think I’m filming up here? It’s just my face, some domed buildings in the background, and a lot of sunshine. What’re you protecting? It’s not a military installation. I’m buggered if I’m going to be hurried by you.

But I also know that the Middle Eastern way is to move from bald-faced lieing to apparent humility and submission, smug in the knowledge that you’ve got what you want. So I let him think he was having his way.

Twenty minutes later, when David and I passed the reception desk on our way out, I stopped to wave my thanks to the Austrian. Never leave anyone with a nasty taste in their mouth. Arabs taught me that. The kisses on the cheeks they bestow after a dispute really do defuse all the tension.

He ignored me. A Palestinian would never have done that.

Here’s the video David and I made.

The Austrian Hospice of the Holy Family is a beautiful sandstone building on the corner where the Via Dolorosa turns briefly onto the main alley of the Muslim Quarter’s souq. Buzz at the main gate, climb up two flights of enclosed steps, and you’re in a palm-shaded garden fronting a broad, four-story façade. Nearly 150 years old, it was built for Catholic pilgrims and for much of the second half of the last century was an insanitary hospital. Now returned to its original Austrian owners, it’s a hotel for church groups visiting the historic sites of Jerusalem.

From its roof, there’s a panoramic view of the Old City. It’s for this that I labored up the front steps with my friend, videographer David Blumenfeld, and his numerous camera bags, lights and reflector shields, last month. We’d already filmed a promo video for my next novel THE FOURTH ASSASSIN in my favorite seedy Old City café, where I shone with sweat, swallowed cardamom-flavored coffee and sucked on a foul nargila, until I looked sufficiently like an inveterate marijuana-user coming down. Now it was time for a second video.

I approached the front desk of the Hospice in the large marble entrance hall. A blonde man in his twenties greeted me: “Grüss Gott.” I’m a lover of things Austrian, so I had a good feeling already.

“Grüss Gott. We’re making a short video for my website. Can we film on the roof?”

“It’s not allowed, unless you have permission.” Not unfriendly. Just stating the rules.

But I’ve lived in the Middle East long enough to know that there ARE no rules. “Don’t worry. It’s really nothing. It’s just for my website. To tell people about my book.”

“What is the book?”

The truth: It’s about a Palestinian teacher who goes to visit his son in New York and discovers a headless body in his son’s bed. No, I’d better not tell him that. It doesn’t sound like something he’d want a pilgrim hostel associated with. How about this? “It’s about Palestinians and how they live their lives.”

A bit more of this and the Austrian was thinking hard. “Ok, but just for ten minutes.”

“Of course, thank you. That’s very kind of you. Ten minutes, of course.” In the Middle East, one of the things that really gets me down is that putting one over on someone else isn’t seen as a bad thing to do. If you can get away with it, then good for you. Naturally when I get the opportunity to do this, I have a feeling of payback for all the times I’ve been deliberately misled by the locals. With that warm sensation, I ascended in the Hospice’s rickety elevator.

Up on the roof, the afternoon sunshine was too bright to film. It was so harsh I’d have been squinting into the camera like Clint Eastwood. So David and I descended to the Hospice’s garden café. For a mere 100 shekels ($30) we had a slice each of strudel (an uncommon dish in Jerusalem, where even Israelis who arrived as immigrants from Austria tend to eat Middle Eastern style), some soda and coffee.

Suitably refreshed we returned to the roof and soldiered on, despite the insanely bright sunshine.

Despite the occasional loud Israeli on a cellphone and the Korean tourists who stopped taking photos of the Dome of the Rock so they could photograph me, I managed to read most of the first chapter of THE FOURTH ASSASSIN without a pause.

Then, just before I’d finished, from the corner of my eye I spy the blonde fellow from reception striding toward me.

“Sir, you have to stop now. This has been more than 10 minutes,” he said.

“We’ve only been working a few minutes. We were down in the café most of the time. We had strudel.”

He twisted his face as though his finger had just gone through the toilet paper. “And I should believe you?”

“Yes, why would I lie? Go and ask the people in the coffee shop.”

I feel for this Austrian. After all, Israelis and Palestinians are able to lie with absolutely no compunction. It’s one of the first things you learn when you live here a while. I could see that this poor fellow had been at the front desk of the Hospice for a sufficient time to train him to recognize a lie, but not long enough to give him the graceful Arab ability to maneuver around someone else’s untruths without humiliating them. This fellow had only two options: let me get away with it, or kick me out.

“So five more minutes and then you’re out,” he said.

Here’s where my own cultural training came in. The over-emotional Welshman in me wanted to say: Listen, butty, I paid 100 shekels for some stiff strudel in your café, so you can bloody well calm down. In any case what do you think I’m filming up here? It’s just my face, some domed buildings in the background, and a lot of sunshine. What’re you protecting? It’s not a military installation. I’m buggered if I’m going to be hurried by you.

But I also know that the Middle Eastern way is to move from bald-faced lieing to apparent humility and submission, smug in the knowledge that you’ve got what you want. So I let him think he was having his way.

Twenty minutes later, when David and I passed the reception desk on our way out, I stopped to wave my thanks to the Austrian. Never leave anyone with a nasty taste in their mouth. Arabs taught me that. The kisses on the cheeks they bestow after a dispute really do defuse all the tension.

He ignored me. A Palestinian would never have done that.

Here’s the video David and I made.

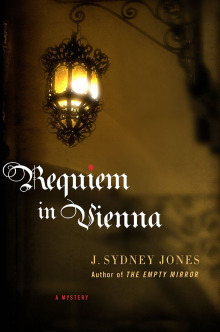

From Hitler History to Mahler Mystery: J. Sydney Jones’s Writing Life

Some authors exude the pleasure of reading and writing (and, believe me, when you meet them, you’d be surprised how many just don’t.) J. Sydney Jones is such a writer, with a breadth of writing experience in an array of genres that’s highly impressive and carries with it an obvious love of his craft. His Viennese Mystery series is a fascinating way to delve into one of Europe’s loveliest, most cultured cities – and damned entertaining, too. He’s also the man behind a great new blog Scene of the Crime, which focuses on the role of place in crime fiction – check out Syd’s interview with Berlin noirmeister Philip Kerr. Here Syd discusses his career and his ideas about writing.

Some authors exude the pleasure of reading and writing (and, believe me, when you meet them, you’d be surprised how many just don’t.) J. Sydney Jones is such a writer, with a breadth of writing experience in an array of genres that’s highly impressive and carries with it an obvious love of his craft. His Viennese Mystery series is a fascinating way to delve into one of Europe’s loveliest, most cultured cities – and damned entertaining, too. He’s also the man behind a great new blog Scene of the Crime, which focuses on the role of place in crime fiction – check out Syd’s interview with Berlin noirmeister Philip Kerr. Here Syd discusses his career and his ideas about writing.How long did it take you to get published?

I started out in journalism, so I had a sense of accomplishment right off, publishing my travel pieces in newspapers and magazines all over the place. Books are a different animal, but again I went with travel first and had some good early success with walking, hiking, and cycling guides. I wrote eight novels, though, before I got my first one, Time of the Wolf, published.

With the current “Viennese Mystery” series, things were easier. I had a bit of an author platform with several well-received books about Vienna and an agent who is most savvy. First query landed us the book deal.

Would you recommend any books on writing?

Tried and trusted here: you can look a lot further and do a lot worse than E.M Forster’s Aspects of the Novel. Another classic is Percy Lubbock’s The Craft of Fiction. These will not be everyone’s cup of tea, but I just love the erudite discussions in both.

What’s a typical writing day?

I get to work about nine in the morning after I drop my son off at school. I try to devote the first hours of the writing day to the current fiction project--currently the fourth book in the Viennese Mystery series. Then some exercise--tennis, if I am lucky--and lunch, followed by more mundane freelance stuff in the afternoon that also helps to pay the bills.

Plug your latest book. What’s it about? Why’s it so great?

Each of the books in the Viennese Mystery series features a famous historical figure of Vienna 1900. Requiem in Vienna focuses on musical Vienna: the composer Gustav Mahler is the target of an assassin and my protagonist, the lawyer and private inquiries man, Karl Werthen, is hired to protect him. The books are a blend of historical whodunit and literary thriller with more than a dash of historical/cultural/food lore thrown in.

Here’s what a Kirkus Reviews critic had to say of the current series installment: “Sophisticated entertainment of a very high caliber.”

How much research is involved in each of your books?

There are decades of research in the books. Explanation: I started researching Vienna 1900 long ago for my book, Hitler in Vienna. Since then I have continued to read heavily in the period, but for each book I still need to bone up on the historical folks I am featuring. Some writer once said that research was sort of like writing without the creative sweat. I enjoy the research; I probably commit about three months to each before I even begin the plotting. And thank whomever for the Internet--I can even get full editions of Viennese papers of the time online.

Where’d you get the idea for your main character?

Karl Werthen is a successful lawyer and sometimes inquiry agent, an assimilated Jew, and a distinct Viennophile. And I haven’t got a clue to where he comes from, other than a shared love for Vienna. He just appeared full-formed on the first page of The Empty Mirror, the initial in the series. A minor character, he elbowed his way to the forefront by the end of the first draft; the series concept actually had the real-life father of criminology, Hanns Gross, as the protagonist. A crusty old curmudgeon, Gross tugs Werthen away from his safe wills and trusts gig back into criminal law in that first one, to prove the artist Gustav Klimt innocent of murdering his model. But it just worked out so much better to use Werthen as my lead and Gross, the pompous pro, as the sometimes sidekick.

What’s your experience with being translated?

Somewhat odd. For example, my Hitler in Vienna was first published in Germany. I originally queried publishers there in German, and it was bought sight unseen (Hitler, at the time, was a hot topic). When they received my doorstopper of a manuscript in English and realized it needed to be translated, they were none too pleased. But they sucked it up and published anyway.

Then when trying to sell the English-language rights, I had a hell of a time convincing editors in England and the U.S. that no, they would not have to have the book translated. I already had the English original of the manuscript.

What books have influenced you?

As a young man I loved the lyricism of Steinbeck. Lee from East of Eden is still one of my favorite fictional characters. And of course there was Hemingway and Fitzgerald. Then during the almost twenty years I lived in Vienna, I became an avid reader of nineteenth- and twentieth-century British authors. Blame it on the British Council. A wonderful resource in its day with massive armchairs around a humming ceramic stove. Thomas Hardy became my literary hero; I open one of his novels and begin reading his scene-setting on some desolate heath in the south of England, and I get actual chills. The language just works for me. And Conrad. Don’t even get me started on Conrad--and the bugger wrote in a second language! A guilty pleasure also became the works of J.B. Priestley, especially his Good Companions.

Did these books influence my writing? Who knows, but they surely have made my life fuller. Le Carre, of course, pushed me in new ways with dialogue and plot, as did the early fiction works of Paul Theroux (Saint Jack, Picture Palace). I wish I could make my dialogue sparkle and crack they way those guys do. But this catalogue could go on for some time. Basta.

Thanks, Syd. Fascinating insights.

Thanks for the opportunity to chat, Matt.

Published on February 18, 2010 02:11

•

Tags:

aspects-of-the-novel, austria, berlin, berlin-noir, crime-fiction, e-m-forster, exotic-fiction, fitzgerald, gustav-mahler, hemingway, hitler, interviews, j-sydney-jones, john-le-carre, joseph-conrad, karl-werthen, matt-beynon-rees, paul-theroux, percy-lubbock, philip-kerr, requiem-in-vienna, scene-of-the-crime, steinbeck, the-craft-of-fiction, vienna, writing-life

Into costume: My book promo Pt. 1

My new book MOZART’S LAST ARIA will be out in the UK in May. Naturally this means a revamp for my website (coming soon) and a new promo video (coming about the same time) to be posted to Youtube. You know, all the stuff writers actually get into the business of writing in order to do. That, and cashing the massive cheques, of course. Oh, and the groupies who throw their panties at you at book-store readings. And the drugs.

My new book MOZART’S LAST ARIA will be out in the UK in May. Naturally this means a revamp for my website (coming soon) and a new promo video (coming about the same time) to be posted to Youtube. You know, all the stuff writers actually get into the business of writing in order to do. That, and cashing the massive cheques, of course. Oh, and the groupies who throw their panties at you at book-store readings. And the drugs.Anyhow, that’s enough digression, even for a blog post. So back to the point: All my previous video clips – which can be viewed on my website – have necessitated no more than a jaunt to Nablus, Gaza or Bethlehem, where I’ve been filmed chatting about the latest adventures of my Palestinian sleuth Omar Yussef. This time, I have to recreate the world of Vienna, 1791, for my historical mystery.

For the novel, creating the atmosphere, the details and the locations of Vienna during Mozart’s time brought me to amass a few shelf-loads of research, to learn piano so I could play some Mozart, and to travel in Austria and Central Europe.

The video places a few more demands. This week I’ve been getting into costume.

I found a theatrical costume shop on a tiny alley in the oldest part of West Jerusalem just off Jaffa Road. Run by a delightful, bustling French lady named Francoise Coriat, the compact store is packed up and down (hanging from the ceiling too) with pirate suits, musketeer costumes, and every other period-wear you’d ever need. Mostly Francoise hires them out to theaters.

She kitted me out with two big flouncy dresses for the two female musicians who’ll feature in the video and three frock-coat suits for the men. And a Little Mozart costume for my three year old son.

Then it was time to figure out exactly how to film it. My videographer pal David Blumenfeld produces new equipment each year when it’s time for me to get a video done. This time he has a little slide to mount on top of his tripod; put the camera (these things are so small these days) on it and you can make a dolly shot that looks positively cinematic. His lighting is increasingly creative too. So I was sure it’d look great.

I worked up a script last week, aiming to make the video seem more like a movie trailer than the more documentary/journalistic style of most of my previous promos. Why? Well, first because MOZART’S LAST ARIA isn’t based on a topic you’re used to seeing featured in the news – whereas Palestinians, unfortunately for them, are very much in the news. Morever, it seems to me people are used to reading novels which are like movies – almost entirely visual, very little of the internal narrative of novels written a century ago – so perhaps book promotional videos ought to be that way too. This is how we think of stories these days.

True, said my friend Matthew Kalman, a journalist based here in Jerusalem who’s also a filmmaker. But beware, he said, that you don’t expect amateur actors to…act.

Read the rest of this post on my blog The Man of Twists and Turns.

Published on December 30, 2010 02:03

•

Tags:

austria, bethlehem, book-promos, book-videos, crime-fiction, gaza, historical-fiction, jerusalem, mozart, mozart-s-last-aria, my-books, nablus, omar-yussef, palestine, palestinians, videos, youtube-com

Mozart Scene of the Crime

Historical novelists recreate the emotions and events of distant times. It helps if they can use real places that still exist. In the case of MOZART’S LAST ARIA, I was able to set much of the action in streets and buildings where Mozart lived and worked – and where you can still visit.

Historical novelists recreate the emotions and events of distant times. It helps if they can use real places that still exist. In the case of MOZART’S LAST ARIA, I was able to set much of the action in streets and buildings where Mozart lived and worked – and where you can still visit.In my historical thriller, the composer’s sister Nannerl comes to Vienna to investigate her suspicion that Wolfgang was poisoned. One of the men who helps her is Baron Gottfried van Swieten, an important patron of her brother. Swieten was Imperial Librarian, and you can see the majesty and learning of that time arrayed on the shelves of the Prunksaal, the great library attached to the Hofburg, the Emperors’ palace in central Vienna.

The library is open to the public, but you’ll rarely find more than five or six other visitors there at one time – most people are shuffling with the crowds through the Emperor’s rooms down the way. It’s a gem hidden in rather plain site.

The house where Mozart died was destroyed some time ago (though you can visit a museum in the house where he wrote The Marriage of Figaro nearby). There’s a department store there now, on Rauhenstein Lane. But if you stand with your back to the spot, you can look to your left, your right, and in front of you, and you’ll see just what Wolfgang would’ve seen – except there’ll be less horse manure on the streets. Much of central Vienna remains just as it was in Mozart’s time.

Despite its destruction, I was able to describe the interior of Mozart’s home quite fully, however. There have been a number of academic theses written about the furniture and layout of the apartment. Yes, really. (Some years ago, the startling discovery was made that not only did he have two windows on the front of his studio, but he also had another one on the side. You get a Ph.d. for this stuff, you know. But anyway I’m very grateful to those dedicated Mozartians.)

You can look at a photo tour of other Mozart sites and locations from MOZART’S LAST ARIA in Vienna on my website.

Read the rest of this post on my blog The Man of Twists and Turns

Published on May 02, 2011 23:36

•

Tags:

amadeus, austria, classical-music, crime-fiction, czech-republic, historical-crime, historical-fiction, mozart-s-last-aria, nannerl-mozart, prague, vienna, wolfgang-amadeus-mozart, wolfgang-mozart

Long gestation and the crime novel

Crime novelists generally write a novel a year. It’s what publishers want. Some big writers—and I mean, 25 million books sold—have told me their publishers and agents complain that if they don’t produce a book a year their readers will forget them.

Crime novelists generally write a novel a year. It’s what publishers want. Some big writers—and I mean, 25 million books sold—have told me their publishers and agents complain that if they don’t produce a book a year their readers will forget them.In the case of such writers, some of those 25 million may have degenerative diseases and others may be plain stupid, but in all likelihood about 24 million of them will remember a writer whose book they read, let’s say, two years ago.

Nonetheless the expectation remains that a book a year will be forthcoming. So do all crime writers have one good idea a year? Or do ideas take longer to gestate? And if they do, where does that leave the writer who needs to get words on paper right now.

In the case of my latest novel MOZART’S LAST ARIA (out now in the UK, but not until November in the US), it was eight years between the initial idea and publication. A most un-crime-fiction-like timescale.

It began with a trip I took with my wife into the Salzkammergut, to find peace among the mountains and lakes at a time when we were living through the Palestinian intifada in Jerusalem. There we stumbled across the remote house where Mozart’s sister Nannerl had lived and a fascination with her was born.

It was nurtured through future visits to Vienna, to Prague (where Mozart’s operas are still performed in the Estates Theater, scene of his “Don Giovanni” premier), dinners with Maestro Zubin Mehta at which we discussed our mutual admiration for the great composer (though it shan’t surprise you to learn that his understanding of the music is on a somewhat, ahem, more elevated level than mine…)

Read the rest of this post on my blog The Man of Twists and Turns.

Published on May 18, 2011 23:55

•

Tags:

austria, brooklyn, crime-fiction, detective-fiction, evan-fallenberg, intifada, jerusalem, little-palestine, mozart-s-last-aria, nannerl-mozart, palestine, piano, prague, research, salzkammergut, vienna, wolfgang-amadeus-mozart, wolfgang-mozart, writers, zubin-mehta